Abstract

Why did substantial parts of Europe abandon the institutionalized churches around 1900? Empirical studies using modern data mostly contradict the traditional view that education was a leading source of the seismic social phenomenon of secularization. We construct a unique panel dataset of advanced-school enrollment and Protestant church attendance in German cities between 1890 and 1930. Our cross-sectional estimates replicate a positive association. By contrast, in panel models where fixed effects account for time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity, education—but not income or urbanization—is negatively related to church attendance. In panel models with lagged explanatory variables, educational expansion precedes reduced church attendance, while the reverse is not true. Dynamic panel models with lagged dependent variables and instrumental-variable models using variation in school supply confirm the results. The pattern of results across school types is most consistent with a mechanism of increased critical thinking in general rather than specific knowledge of natural sciences.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Secularization, understood as churches’ loss of importance in society, is a European phenomenon that was particularly strong during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and brought fundamental change to societies. Important aspects of this can be observed from the practice of religious participation. For example, in our micro-regional German data, participation in Holy Communion per Protestant declined on average by nearly a third of its initial value from 1890 to 1930. Understanding the sources of this seismic religious change is important: by shaping attitudes towards factors such as education and knowledge diffusion, the religious orientation of society may have important repercussions for long-run development (Galor 2011).Footnote 1 Furthermore, while it is hard to observe changes in religious beliefs in the historical context, declining religious participation in itself has important societal meaning because of the historical role of the institutionalized church in society at large. However, despite heated academic debates, empirical evidence on the sources of this dramatic social change is scarce. In this paper, we use city-level panel data to estimate how advanced education affected religious participation in Germany’s secularization period around the turn to the twentieth century.

Classic secularization hypotheses suggest economic development and education as two dimensions of modernization that may affect religious participation. Our focus is on the effect of education. As argued by many eminent scholars, increased education may have been a leading source of secularization because increased critical thinking and advanced scientific knowledge may have reduced belief in supernatural forces (e.g., Hume 1757 [1993]; Freud 1927 [1961]; cf. McCleary and Barro 2006a). Cross-sectional evidence generally contradicts this view and finds a positive association between education and church attendance (Iannaccone 1998), and modern cross-country and individual panel analyses come to mixed results. However, it is unclear how these results transmit to the context of actual decade-long societal developments during important historical phases of secularization.

To provide evidence from an historical setting of massive secularization, this paper constructs a unique panel dataset on education and Protestant church attendance in German cities from 1890 to 1930. This dataset allows us to estimate panel models with fixed effects that exploit city-specific variation over time. While cross-sectional associations between education and religious participation may well emerge from bias due to omitted variables—for example, more orderly people may go both to church and to school—the use of city and year fixed effects takes out unobserved time-invariant city characteristics and common trends.

In our panel fixed effects models, we find that enrollment increases in advanced schools are significantly related to decreases in church attendance. These panel estimates are in strong contrast to cross-sectional models, which indicate a positive cross-sectional association between advanced education and church attendance in the same data. In contrast to education, changes in measures of income (municipal tax, income tax, or teacher income) and urbanization (city population) as alternative dimensions of modernization are not significantly related to changes in church attendance, confirming recent related work at the county level (Becker and Woessmann 2013).

The main result is confirmed in a series of robustness tests. In particular, we control for contemporaneous changes in potentially confounding variables such as the demographic composition of the city (age and gender structure and migration patterns), the educational environment (opening of universities and emergence of secular schools), the economic environment (industry structure and welfare expenditure), and the political environment (emergence of secular movements and nationalistic sentiment). Results are also robust in alternative specifications of the education variable and in subsamples.

The significant negative effect of advanced-school enrollment on church attendance is also confirmed in dynamic panel models. First, models with different lag structures of the education variable indicate that the effect of advanced-school enrollment is strongest after about 10 years (the second lag), speaking against bias from reverse causation and suggesting that the effect of advanced education on religious participation materializes over time. By contrast, lagged church attendance does not predict advanced-school enrollment. Second, results are robust in models with lagged dependent variables to account for persistence in church attendance over time. Third, while a demanding specification in our setting, basic results are also robust to the addition of city-specific linear time trends.

Results are also confirmed in an instrumental-variable specification that uses the number of advanced schools in a city as an instrument for advanced-school enrollment. To avoid identification from potentially endogenous demand-side enrollment decisions, this model restricts the analysis to changes in the supply of schools and exploits variation in advanced-school enrollment that originates from the opening and closing of advanced schools in a city.

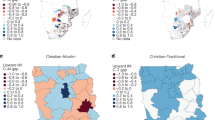

Finally, we use enrollment in different types of advanced schools that have different curricula to explore potential mechanisms of the effect of advanced-school enrollment on religious participation. While imprecisely estimated, the coefficients of the different school types indicate that results are at least as strong for the classical humanistisches Gymnasium with its curriculum focused on classical languages (and for the Realgymnasium with its focus on modern languages) as for the newly emerging Oberrealschule with its strong curricular focus on natural sciences. This pattern is more consistent with a leading role for the general conveyance of critical thinking in advanced schools in undermining belief in the institutionalized church than with a specific role for the teaching of scientific knowledge of facts of natural sciences.

Our paper addresses the effect of advanced education on religious participation in a leading historical period of secularization, using city-specific variation within one country over several decades. As such, it complements the existing literature on the effects of education on secularization that uses cross-country or modern-day individual-level variation (as summarized in greater detail in Sect. 2.2 below) by providing insights into the mechanisms and reasons of a fundamentally important social phenomenon in Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. It is particularly noteworthy that in our context, the cross-sectional pattern is turned around in the panel analyses, suggesting that the cross-sectional identification is likely to suffer from severe identification problems. Our panel evidence suggests that in the historical context of Germany around the turn to the twentieth century, educational expansion was negatively related to religious participation, confirming traditional secularization hypotheses during an historical period of mass secularization when these lines of reasoning were very prominent but lacked empirical validation.

In what follows, Sect. 2 provides a conceptual background and reviews the literature. Section 3 gives the historic and institutional background for Germany at the turn of the twentieth century. Sections 4 and 5 introduce our data and empirical model. Section 6 reports our basic results and different robustness checks. Sections 7 and 8 extend the analysis to dynamic panel models and instrumental-variable estimation, respectively. Section 9 explores specific mechanisms by analyzing effects of different types of advanced schools that have different curricula. Section 10 concludes.

2 The role of education in secularization

To frame the empirical analysis of this paper, we start by providing a conceptual background. We introduce the concept of secularization and its relationship with education and economic development as discussed in modernization theories and summarize the available empirical evidence on the relationship between education and religious participation.

2.1 Conceptual background

Secularization A standard dictionary definition of secularization is that “Secularization is the transformation of a society from close identification with religious values and institutions toward nonreligious values and secular institutions.”Footnote 2 This definition shows the multi-faceted nature of the general concept of secularization that needs specification in our concrete historical context.

Contemporaries noted a marked decline in church attendance between 1870 and World War I (WW I) and were concerned about the “decay” in religiosity (see Hölscher 2005). Church attendance was interpreted as an indicator of a seismic change in society. Nipperdey (1988) confirms the loss in churchliness at the time and draws on selected statistics of the Protestant and Catholic churches to illustrate the process of secularization.

Following this empirical tradition, in our analysis we draw on statistics on participation in Holy Communion that we describe in more detail below. Given the lack of surveys in this early period, it is obviously impossible to capture directly what went on in people’s minds and whether decreased involvement in church went hand in hand with a loss of faith, or whether it was merely an expression of lack of interest in religious services provided by the church. But clearly the church used to be one of the pillars of society in Prussia and the German Empire: in 1861, the Prussian King Wilhelm I, who went on to become Germany’s first Emperor, was crowned in a church: the castle church of Königsberg. Several churches in Berlin commemorate German emperors and their family: the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtniskirche commemorates Wilhelm I, the Kaiserin-Augusta-Kirche commemorates his wife Augusta von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach, the Kaiser-Friedrich-Gedächtniskirche commemorates Emperor Friedrich III who reigned for only 99 days in 1888. Given this prominence of the church in public life, the marked decrease in support for the church is remarkable and warrants an analysis of the factors behind it during this period of rapid change.

Secularization hypotheses take various forms (see McCleary and Barro 2006b) and highlight the fact that different dimensions of modernization may have differing relevance for religious participation. On a broad scale, we may distinguish between aspects of economic development and aspects of education.

Economic development and secularization There are at least two important aspects of economic development that have been discussed as potential factors affecting secularization—income and urbanization. First, the income aspects is nicely captured by the remark of Marx (1844) about religion as “opium of the people” (p. 72) that is required to alleviate the ailments of poor economic conditions. Along this line of argument, improved material conditions may reduce demand for religious consolation and hence reduce church attendance. Becker and Woessmann (2013) address the relation of income and secularization for the historical context studied here and find no effect of increased income on church attendance in a sample of Prussian counties. Their sample differs from this paper in two dimensions: here, we use data at the city rather than county level and cover data from across the German Empire, not just Prussia.

Second, a closely related but conceptually distinguishable aspect of economic development is urbanization. Urbanization went along with migration from rural to urban areas, and the adjustment to a new environment brought challenges of its own. On the demand side, a new life in a city environment might have led to an increased interest in attending church in order to meet new people. At the same time, if church attendance in the rural place of origin took place under pressure from relatives and acquaintances, life in the city allowed movers to go their own ways and skip church without being penalized. On the supply side, rapid urbanization might have led to an under-supply of religious services: as already noted by Durkheim (1897), p. 161, the number of Protestant pastors did not keep up with rising population numbers in Germany.Footnote 3 At the same time, urban areas come with higher opportunity costs of religious participation. Cities offer many alternative time uses such as museums and theaters (see McCleary and Barro 2006b, p. 152).

Education and secularization Apart from economic development, education has been discussed as a separate dimension of modernization with a bearing on secularization during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In the German context, Nipperdey (1988) narratively attributes the decline in churchliness to increases in urbanization, technological progress, and the advancement of a rational view on the world. Increased education may have been a leading source of demand-induced secularization, even after controlling for income and urbanization. In one form or another, this view on education and religiosity has been advanced by such eminent scholars as Hume (1757 [1993]), Marx (1844), Weber (1904 [2001]), and Freud (1927 [1961]), among many others.

There are again two separate general aspects of education discussed as possible determinants of secularization, which we may refer to as critical thinking and scientific knowledge. First, education may foster critical thinking. The education ideal introduced by Wilhelm von Humboldt at the beginning of the nineteenth century, which governed the Prussian education system at the time, was a holistic one: to integrate the arts and sciences with research to achieve both comprehensive general learning and cultural knowledge. To the extent that this education ideal leads to emancipation of thinking, students may increasingly oppose established “old-fashioned” institutions such as the church. This may or may not go hand in hand with changing religious beliefs. Still, to the extent that sermons are an important channel by which the church can exert influence over its members, reduced church attendance likely implies a loss of influence in society and its development.

Second, schools may also teach scientific knowledge and findings that may be conceived as being in direct opposition to established religious beliefs. McCleary and Barro (2006b) summarize this view as follows: “one argument for secularization is that more educated people are more scientific and are, therefore, more inclined to reject beliefs that posit supernatural forces” (p. 151).Footnote 4 While the school curriculum featured religious education all the way throughout our sample period, it is clear that students were exposed as well to scientific discoveries that had the potential to challenge religious views. Some may have concluded that God and the church as provider of religious services are no longer necessary to make sense of the world and to cope with life. Increased education may thus have translated into lower church attendance.

Education may influence church attendance directly via its effect on students themselves who no longer go to church. It may also exert indirect effects, for example, via table talks with parents or via a changing intellectual climate in a city. For example, Thomas Mann’s novel Die Buddenbrooks that traces the life of a German nineteenth-century dynasty over several generations famously exemplifies both the decline in attachment to religion and the central role played by conversations in exchanging views across several generations of the family. Interestingly, during the period of analysis natural history museums were founded across German cities and several natural-science magazines started publication. For example, Der Naturforscher, a weekly magazine started in 1868 “to promote the advances of the natural sciences” and explicitly targeted the educated of all classes (für Gebildete aller Berufsklassen). In an environment where scientific ideas are being taught and consumed by children and adults alike, it may no longer be unspeakable to question God’s existence or the importance of church in society.

Implications for the empirical analysis and its interpretation The focus of this paper is to investigate how education affected religious participation during Germany’s secularization period around the turn to the twentieth century. Because education is correlated with income and urbanization, it may be empirically challenging to separately identify their effect. In an attempt to isolate the effect of changes in education above and beyond changes in income and urbanization, all our empirical models will take these alternative mechanisms of economic development into account. In addition, Sect. 6.4 provides detailed analyses and discussion of the bearing of different measures of economic development, considered jointly and individually, for our results on education.

Our empirical analysis will also address specific mechanisms by which education may affect religious participation. Apart from the possible effects of education working through income and urbanization, Sect. 6.2 will analyze the extent to which the empirical effect of education on church attendance is mediated by contemporaneous changes in a series of other factors such as the sectorial structure of the economy, the emergence of secular movements, or nationalistic sentiment that may in part capture mechanisms by which education affects church attendance. In Sect. 9, we make use of the differential curricula of different types of advanced schools to differentiate between critical thinking and scientific knowledge as two separate possible mechanisms by which education may affect religious participation.

Ultimately, our empirical analysis will thus capture one important dimension of secularization in the form of lower church attendance and demonstrate that it is partly driven by increased enrollment in advanced schools, in particular in those types that may mostly convey critical thinking in general. These empirical results do not imply that advanced scientific knowledge is incompatible with belief in God or that education is generally hostile to religious participation. They show that, in this historical setting, increased advanced schooling was related to declining church attendance, an indication of secularization understood as the loss of influence of the organized church. Education may well have led people who believe in God to break with the institution of the church, without weakening their belief in God. It is also possible that, for example, people who did not have a strong belief in God in the first place were led by education to abandon their custom of attending church. Still, the results show that increases in advanced education were closely related to people’s reduced active involvement with the institutionalized church and its rituals, one of the most seismic changes in social history since the nineteenth century.

2.2 Existing evidence on education and secularization

Despite heated academic debates about secularization, empirical evidence on the sources of this phenomenon is scarce. In the sociological literature, this debate has been going on for a long time (Sherkat and Ellison 1999). The existing evidence, which is mostly cross-sectional, is generally not in line with the traditional view that education reduces church attendance. Iannaccone (1998) summarizes the literature as follows: “In numerous analyses of cross-sectional survey data, rates of religious belief and religious activity tend not to decline with income, and most rates increase with education” (p. 1470).

Similarly, in a cross-country analysis, McCleary and Barro (2006b) find that while religiosity is negatively related to overall economic development,Footnote 5 it is actually positively related to education. A positive effect of education on religiosity could be explained by alternative hypotheses based on advantages of educated people in the kind of abstract thinking required for religion (McCleary and Barro 2006b) or based on educated people getting higher returns from social networking in church (Glaeser and Sacerdote 2008). In contrast, Ruiter and Tubergen (2009), Bettendorf and Dijkgraaf (2010), and Deaton (2011) find negative associations of education with indicators of religiosity in cross-country analyses, although not uniformly across all countries.

It is, however, not clear to what extent the existing cross-sectional findings suffer from omitted-variable bias. For example, in cross-sectional studies finding a positive association between education and church attendance, it is easily conceivable that more orderly people are more inclined to go both to church and to school, that more conservative people put particular emphasis on religious rituals and on educational achievement, or that communities that are more inclined to collective action organize educational infrastructure and enjoy church community. These examples would give rise to a positive correlation between education and church attendance that does not necessarily stem from a causal effect of education.Footnote 6 Recent evidence from modern times underlines such concerns with cross-sectional studies. When exploiting exogenous variation from changes in compulsory schooling laws, Hungerman (2014) finds that education led to a reduction in reported religious affiliation in Canada in post-WW II data. Similarly, recent psychological evidence from randomized laboratory experiments where participants are primed with analytic processing before being asked about their belief in God suggests that analytic thinking promotes religious disbelief (Gervais and Norenzayan 2012).Footnote 7 However, it is unclear how such modern experience from short-term lab interventions transmits to the analysis of decade-long societal developments during important historical phases of secularization.

The few studies that use panel data models to study the relationship between education and church attendance are either based on recent micro data for individual countries or on cross-country data from the twentieth century. Brown and Taylor (2007) find a positive association between education and church attendance in fixed effect panel regressions based on individual-level data from the British National Child Development Study. By contrast, applying fixed effects regressions to individual-level data from the U.S. Monitoring the Future survey, Arias-Vazquez (2012) finds that education has a negative effect on religiosity at the individual level.

Most closely related to our work in terms of a long-run view is the study by Franck and Iannaccone (2014) who construct a cross-country panel data set for 10 countries over the period 1925–1990 to identify determinants of church attendance. Using fixed effects estimation, most of their specifications do not indicate a statistically significant effect of educational attainment on church attendance. But government spending on education has a consistent negative effect on church attendance in their models, which may indicate a particular role for how governments shape the content of schooling.

To our knowledge, our analysis is the first to take a within-country regional view over an historical period of several decades. Our analysis complements the studies based on cross-country data and on modern-day individual-level data by going back to a crucial period of secularization in a core European country during which church attendance decreased long before official church membership figures declined. Observing this social phenomenon over various decades goes beyond what modern setups can possibly capture. Compared to cross-country analyses, our sub-national analysis of regional variation within a country stays within a given set of national institutions within a limited geographic area and thereby largely conditions out institutional and geographical variation that is harder to control for in cross-country regressions.

3 Institutional background: Germany around the turn to the twentieth century

This section provides some historical and institutional background on Germany around the turn to the twentieth century. It documents the dramatic decline in church attendance in the context and provides details on the system of advanced schools in Germany during our period of interest.

3.1 A crucial phase of secularization

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Western Europe underwent a profound process of secularization (see McLeod 2000). While the very concept of secularization has been questioned for the United States (e.g., Finke and Stark 1992), it is generally accepted that key indicators of secularization, in particular reduced church attendance, have been “dramatically increasing” in Western Europe (Berger 1996).Footnote 8 For instance, Becker and Woessmann (2013) find that church attendance fell by 3.6% points per decade, on average, across Prussian counties between 1850 and 1931. Froese and Pfaff (2005) document similar trends for selected regional Protestant churches (Landeskirchen) in East Germany between 1862 and 1939.

Our own data (see Sect. 4 below for details) also document a strong process of secularization during our period of study in Germany. For our sample of 61 German cities over the period 1890–1930, panel estimates with city fixed effects reveal a statistically highly significant average decrease in our measure of church attendance of Protestants by about 2% points per decade.

The period and location we study is therefore of chief interest when analyzing the determinants of the process of secularization. In fact, the very religious census that our analysis draws on was established mainly to analyze the “decay” in religiosity in Germany (Hölscher 2005), indicating a process of secularization observed by the clergy. This is also confirmed in Hölscher (2001), who locates the process from the late eighteenth century onwards.Footnote 9 Nipperdey (1988) supports the existence of this process and points to a large decline in church attendance between 1870 and 1912. As the Protestant Church in Germany gives considerable weight to the institutionalized church as a community of believers, declining religious participation has important bearing for the role of the institutionalized church in general.

3.2 The system of advanced schools

Before World War I, the school system in Germany had three distinct tracks (see Konrad 2012; van Ackeren et al. 2015). The lowest of the three tracks, elementary schools or “people’s schools” (Volksschulen), ran for 8 years, from age 6 to 14. Middle schools (Mittelschulen or Realschulen), the middle track, ran for 9 years, from age 6 to 15, with the first three school years designated as preparatory classes (Vorklassen). The highest track are advanced schools (Höhere Unterrichts-Anstalten), which ran for 12 years, for students aged 6–18, again with the first 3 years designated as preparatory classes. The system did, in principle, allow transitions between the three tracks, but they were very rare. The three tracks had a clear tendency to follow a class division where working-class children would generally attend people’s schools, white-collar children middle schools, and upper-class children advanced schools. The advanced schools were restricted to male students, whereas the separate advanced school type for female students (Höhere Mädchenschulen) had a different focus.

The focus of our analysis is on the advanced schools. Variation in enrollment in advanced schools seems particularly relevant to test the traditional view of education and secularization, because advanced schools are most likely to convey the kind of scientific thinking stressed by secularization hypotheses. The focus also reflects the fact that enrollment at the elementary level was as good as universal in Germany throughout our period of observation, in particular in Protestant regions (Becker and Woessmann 2009). Compulsory schooling covered ages 6–14. By the 1880s, enrollment reached 100%, at least in Prussia (Kuhlemann 1991), so there is little if any variation in enrollment in the two lower tracks.

There were three distinct types of advanced schools. The first type, the humanistisches Gymnasium, had a humanistic curriculum that focused on classical languages and literature (Latin and Greek). In particular with the advent of large chemical and electronic enterprises during the second phase of industrialization in Germany, demand for two alternative types of advanced schools emerged rapidly. The curriculum of the second type, Realgymnasium, focused on modern foreign languages (in particular English) instead of Greek. The third school type, Oberrealschulen, had a curriculum with a strong focus on natural sciences and did not include the classical languages. We will use the distinction between the three advanced school types to test whether a particular focus of the curriculum on natural sciences has separate effects on religious participation.

Changes in advanced-school enrollment may affect secularization by exposing more students to material that challenges religious views. However, educational content as such may also change. Indeed, our period of analysis is characterized by two changes that are relevant for the interpretation of our findings. First, in many cities church-run schools were turned into city-run schools. We control for this in our regressions. Second, there were some reforms to the curriculum taught at advanced schools. In Germany’s federal structure, curricula are set at the state level, but making up about half of the German Empire, Prussia generally took the lead in setting standards. The Prussian school curriculum of 1882 has the subject “nature observation,” where observation suggests a descriptive character of what is being taught (Prussian Ministry of Education 1882, p.28/29). In 1892, “elements of chemistry and mineralogy” is added to the curriculum (Prussian Ministry of Education 1892, p.10), and in 1901, “nature observation” is replaced by “science of nature,” pointing to a more analytic character of the teaching content (Prussian Ministry of Education 1913, p.7). In 1907, biology is added to the curriculum as an option (see Prussian Ministry of Education 1913, p.119).

The impact of the new teaching in advanced schools is likely to reach beyond the students taught in the schools themselves. Anecdotal evidence for this comes from the debate about the role of Darwin’s theory in advanced school teaching, which was a matter of debate in the Prussian House of Commons (Preussisches Abgeordnetenhaus). The debate evolved around Hermann Müller, who taught at an advanced school in Lippstadt and covered evolutionary topics in class as early as 1876, which drew the anger of conservative circles. In a parliamentary debate in January 1879, the conservative MP Baron Wilhelm von Hammerstein argued that “in our fatherland, we see a generation growing up whose belief is atheism ...” He declared that references to evolutionary theories are “a travesty of the gospel” and that the “theories and unproven [...] hypotheses expressed in the works of [...] Darwin [...] do not belong into the classroom of the advanced schools” (cited from Dankmeier (2007), pp. 59–60). This suggests that students seem indeed to have been increasingly exposed to critical thinking and scientific material that challenged established religious beliefs and that the impact extended into a larger societal debate.

4 Data

We construct a unique new panel dataset of German cities between 1890 and 1930 that covers measures of both education and church attendance (see Appendix for details).

First, we digitized data on the enrollment in and number of advanced schools (Höhere Unterrichts-Anstalten) from different volumes of the Statistical Yearbooks of German Cities from Neefe (1892) through Deutscher Städtetag (1931).Footnote 10 Covering all German cities with a population over 50,000 inhabitants, these yearbooks regularly report the number of students enrolled in advanced schools. Where available, we also digitized the enrollment and school data for each of the separate types of advanced schools (see above).

Our main measure of the enrollment rate in advanced schools is the number of male and female students enrolled in advanced schools as a share of the city population. Although the number of students who are actually enrolled does not constitute a large part of the Protestant population of a city, the structure of the school system is indicative of a city’s educational orientation as parents arguably decide upon investment in the children’s education. In our view, this measure hence best reflects the overall educational and scientific orientation of the city.Footnote 11

The yearbooks provide us with data for an unbalanced panel of a total of 61 German cities observed over eight waves that cover every 5 years from 1890 to 1930 (with the exceptions that, due to the interruptions of World War I, there are no data for 1920 and values for 1913 are used instead of 1915). Figure 1 shows that the included cities cover all parts of modern-day Germany.

Apart from the education data, the yearbooks also provide us with data to capture the two aspects of economic development discussed above, income and urbanization. Thus, the yearbooks report data on municipal tax per capita, which we use as a proxy for income. In addition, they provide data on the total population of the city, which captures different degrees of urbanization. In robustness analyses, we extend the analysis to two additional proxies for income, the city-level income tax reported in two volumes of the statistical yearbooks as well as Silbergleit (1908), and teacher income collected in education censuses and provided in different volumes of the Preussische Statistik.

We match these data with unique data on church attendance of Protestants. This exceptional database stems from the practice of the Protestant Church to count the number of participations in Holy Communion every year.Footnote 12 At the time, church membership was close to 100% and hardly reveals information about actual religious involvement. In contrast, data on participation in Holy Communion reflects “demonstrations of churchly life ... that were considered already by contemporaries as indicators of churchliness” (Hölscher 2001, p. 4).Footnote 13 As the communion data are based on direct head counts, they also do not suffer from the usual unreliability of survey data on church attendance (Hadaway et al. 1998; Woodberry 1998).Footnote 14

Hölscher (2001) gathered the historical Sacrament Statistics for the modern-day German territory from regional archives, providing data on church attendance as measured by the number of participations in communion divided by the Protestant population (see also Becker and Woessmann 2013). The communion data are available at the level of church districts, which we match to our city database.Footnote 15 Given that advanced schools draw their enrollment both from the city itself and from the surrounding countryside, the availability of the communion data at the church district level (and of the education data only for larger cities) provides a reasonable match.Footnote 16 Throughout, standard errors in all regressions are clustered at the level of church districts. Also, while the church attendance measure refers to Protestants only, educational enrollment refers to the whole city population; models in subsamples of cities with a mostly Protestant population confirm that this is not driving the results (see columns 5–8 of Table 10 in the Appendix).

The number of cities with complete available data for our analysis from both sources increases from 25 in 1890 to 51 in 1930. In total, there are 291 city-year observations over the eight waves in our unbalanced panel.Footnote 17 To compare city characteristics of the initial dataset of up to 522 city-year observations with our estimation sample, Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for both datasets. None of the differences is statistically significant. In the estimation sample, average church attendance is 25%, ranging from 5 to 74%.

In our basic analyses, we report results both for the eight waves of the full period (1890–1930) and separately for the six waves of the period before World War I (1890–1913). We have more confidence in the restricted pre-WW I analysis because WW I has repeatedly been reported to have changed religious beliefs dramatically. For example, Hölscher (2001) reports that society’s trust in the clergy collapsed after WW I throughout Germany. In addition, the fact that the post-WW I period is limited to two waves of data (1925 and 1930, with no data for 1920) precludes extensive analyses in this sub-period, in particular in specifications with lags. Furthermore, several of the additional data sources used in robustness analyses are available only for the pre-WW I period. For many of our robustness analyses, we therefore focus on the pre-WW I sample.

5 Empirical model

The panel setup of our database allows us to estimate panel models with fixed effects that identify the effect of education on religious participation only from within-city variation over time. Such models avoid identification from unobserved time-invariant regional characteristics that may be correlated with both education and church attendance. Specifically, we estimate the following equation:

where \(y_{it} \) denotes participations in Holy Communion per Protestant population, \(\mu _i \) and \(\mu _t \) denote fixed effects for city (i) and time (t), respectively, \(s_{it} \) is advanced-school enrollment per city population, \(x_{it} \) is a set of covariates, and \(\varepsilon _{it} \) is an error term.Footnote 18 Our parameter of interest is \(\gamma \). In the baseline fixed effects specification, the covariates include municipal tax revenues (a proxy for income) and city population (a proxy for urbanization). In a pooled OLS specification that replicates the cross-sectional nature of existing studies, the city fixed effects are replaced by a dummy that indicates whether the city ever belonged to Prussia and the share of Protestants (in 1910, the only year for which this highly stable measure is available at the city level).

The panel fixed effects specification addresses several concerns with identification in cross-sectional models. The inclusion of city fixed effects addresses potential omitted variable bias that may arise from unobserved time-invariant city characteristics. The inclusion of time fixed effects addresses potential bias from nation-wide common trends in the variables of interest. The remaining question is whether such identification from city-specific variation over time can be given a causal interpretation. Our main analysis does not directly model exogenous variation and hence cannot unequivocally claim causal inference. The identifying assumption of the panel fixed effects model is that the change in the dependent variable would be similar across cities in the absence of differential changes in the included explanatory variables. As in most econometric analyses of this kind, the main remaining concerns relate to potential biases from reverse causality, omitted variables, and attenuation due to measurement error. We briefly introduce these concerns here and come back to them in separate sections below where we discuss in greater detail the remaining issues and how the analyses address them.

In principle, reverse causality from religiosity towards decisions about educational investments might still bias the fixed effects models. For example, strong belief in Protestant teaching may increase demand for education (Becker and Woessmann 2009), or religious people may have more children which—through a trade-off between fertility and education—could reduce investment in children’s education (Becker et al. 2010; de la Croix and Delavallade 2015). However, in detailed analyses with different lag structures of the education variable in Sect. 7.1, we show that the time pattern of the effects is consistent with an effect from education on religious participation that materializes over time, whereas there is no evidence of lagged effects of religious participation on education. In addition, in Sect. 7.2 we show that results are robust in dynamic panel models that include the lagged dependent variable, indicating that persistence in church attendance over time is not driving the results. Furthermore, we show that results are robust to the inclusion of city-specific linear time trends, indicating that they do not reflect differential long-term trends in church attendance of cities that may occur for other reasons.

Additional remaining bias could come from omitted variables whose city-specific change over time correlates with changes in the two variables of interest. For example, systematic changes in the composition of a city’s population would not be captured in the fixed effects. Therefore, in Sect. 6.2 we provide a series of robustness specifications that control for contemporaneous changes in other observed factors. In particular, the additional measures include changes in the demographic composition of the city (age structure, gender structure, and recent migration), changes in the educational environment (opening of universities and emergence of secular schools), changes in the economic environment (industry structure and welfare expenditure), and changes in the political environment (emergence of secular movements and nationalistic sentiment). Furthermore, to avoid identification from potentially endogenous demand-side enrollment decisions and to restrict the analysis to changes in the supply of advanced schools, in Sect. 8 we introduce an instrumental-variable model that uses only variation in advanced-school enrollment that originates from changes in the number of advanced schools in a city.

Finally, in our historical data, measurement error in the independent variables is also likely to attenuate coefficient estimates towards zero. It should be kept in mind throughout that in this sense our estimates are, if anything, conservative.

6 Basic results

We start by describing results based on pooled OLS and fixed effects regressions in this section. In Sects. 7 and 8, we look at dynamic panel data models and instrumental-variables regressions, respectively. While in most of our analysis, we use enrollment in all advanced school types combined, in Sect. 9 we use enrollment in different specific advanced school types to analyze potential mechanisms of the main effect.

6.1 Main results

Using the cross-sectional dimension of our data, columns 1 and 2 of Table 2 replicate the common finding from the literature that education is significantly positively associated with church attendance in the cross-section, both in the full 1890–1930 period and before World War I. In the pooled OLS estimation with year fixed effects, an advanced-school enrollment rate that is higher by one SD is associated with 4% points (or 0.26 SD) higher church attendance in 1890–1930.Footnote 19 This positive association is easily visible in a simple scatterplot depicted in panel (a) of Fig. 2 for the example of the year 1900.

Data sources: church attendance: Hölscher (2001) based on Sacrament Statistics; enrollment rate in advanced schools: Statistical Yearbooks of German Cities (Neefe 1892 through Deutscher Städtetag 1931)

Education and church attendance: levels and changes. Scatterplots of church attendance against enrollment rate in advanced schools for German cities, a 1900 levels and b 1890–1913 changes. Church attendance refers to participations in Holy Communion over Protestants. Enrollment rate in advanced schools refers to enrolled students over city population.

When using only within-city variation over time in our baseline panel model with city and year fixed effects, however, this result is turned around (columns 3–4). Increases in education are now significantly negatively related to changes in church attendance.Footnote 20 This pattern is in line with the traditional view that education leads to secularization. In the panel fixed effects estimation, an increase in the advanced-school enrollment rate by one SD is related to a decrease in church attendance by roughly 1.5% points (or 0.10 SD), in both the full and the pre-WW I sample.Footnote 21 This negative association between changes in education and in church attendance is again easily visible in the scatterplot, depicted in panel (b) of Fig. 2 for the pre-WW I period.

To put the magnitude in perspective, consider the 24 cities observed both in 1890 and in 1913: if, rather than their actual mean change in education, they would have only had the change in education of the city at the 10th percentile, the reduction in church attendance would have been 1.3% points smaller. This would account for about one quarter of the actual mean reduction in church attendance of 4.6% points.

The change in the sign of the estimated effect between the cross-sectional and the fixed effects model is consistent with the presence of unobserved time-invariant city-specific characteristics that give rise to a positive correlation in cross-sectional regressions. For instance, a city’s population may have historically been of more conservative attitude, putting a stronger emphasis on educational attainment as well as on institutionalized religiosity—hence the initial positive correlation. However, with an increase in advanced-school enrollment, also these cities witnessed a drop in church attendance over time.Footnote 22

Interestingly, while education yields sizeable and significant estimates in our models, the same is not true for the other measures of modernization. In the baseline specification, we use municipal tax revenue as a proxy for income. The insignificant and positive point estimate for its coefficient casts doubt on the hypothesis that income adversely affected religiosity. This is in line with Becker and Woessmann (2013) who find that, once fixed effects are included, there is no significant effect of income on religious participation. Similarly, the size of the city population as a proxy of urbanization is not significantly related to church attendance. In Sect. 6.4 below, we will get back to the topic of income and religious participation with additional analysis and discussion.

While the panel models with city fixed effects are identified from the 5-year variations within each city, the main result of a negative association between education and church attendance is also visible in long-run changes. For this, columns 5 and 6 report first-differenced models that regress the change in church attendance from 1890 to 1913/1930 on the change in the explanatory variables over the same time periods. Although based on small samples, the first-differenced models confirm the panel fixed effects models, showing that the long-run changes are consistent with the results of the fixed effects models.

6.2 Robustness to contemporaneous changes in other observed factors

While the fixed effects models take care of any time-invariant characteristics that may differ across cities, the main remaining concern is that other factors may change over time in a way related to both education and church attendance. In general, our period of observation was a period of substantial socio-demographic, economic, and political change, and any city-specific incidence of such changes may interfere with our panel analysis. As a first step to address this concern, in a series of robustness specifications we add a number of potentially confounding variables that we observe over time. These potentially confounding variables include age, gender, migration, opening of new universities, emergence of secular schools, industry structure, welfare expenditure, emergence of secular movements, and nationalistic sentiment.

A factor often argued to be relevant for religious participation is the age of a person (e.g., Azzi and Ehrenberg 1975). To control for this potential influence, the first column of Table 3 includes measures of a city’s age structure, namely the shares of under-20-year-olds and of over-60-year-olds. Despite being available only for the census years 1890 and 1910, results in a sample of 66 observations leave the effect of education qualitatively unchanged and even larger.Footnote 23 Both age measures have the expected sign but are statistically insignificant.

While conceptually, the share of advanced-school students in the entire city population is our preferred indicator of a city’s educational and scientific orientation, in this smaller sample we can also calculate the enrollment rate as a fraction of under-20-year-olds. Using this variable leaves the significant negative coefficient on education unaffected, indicating that our results are robust to this change in the measure of education (column 2).Footnote 24

Traditionally, women participated more regularly in church activities, possibly because of lower opportunity costs (Azzi and Ehrenberg 1975). When including the share of females in the model, our result remains robust and the female share is insignificant (column 3).

To account for possible effects of migration on church attendance, we include the share of recently arrived citizens in a city (column 4). The coefficient on the share of new citizens is insignificant and small, and the coefficient on education is qualitatively unaffected.

To ensure that results are not related to foundations of new universities in the cities, column 5 controls for an indicator for openings of new universities, as well as for the share of university students in the city population. Neither enters the model significantly, and the coefficient on the enrollment rate in advanced schools remains qualitatively unaffected.

During our period of observation, some advanced schools changed from being religiously affiliated into non-religious schools.Footnote 25 To the extent that this entailed a change towards a less religious curriculum, our main effect might capture a change in curriculum and educational content rather than an increase in education per se (e.g., Franck and Iannaccone 2014). However, when including the share of Protestant advanced schools in a city as an additional control, it does not enter the model significantly and does not qualitatively change our main result (column 6). Similarly, the share of Catholic or secular advanced schools does not enter the model significantly or change our main result (not shown). The same is true for the total number of advanced schools, indicating that our result does not capture an effect of increased supply of advanced schools, but rather a demand-side effect.

At a very general level, a change that took place in Germany around the time of our analysis is the rise of the modern welfare state under Bismarck. While most of the emerging social legislation was national in character and would thus be captured by the year fixed effects included in our models, it is also conceivable that they affected regions with different economic structures differently. To address this point, the first column of Table 4 adds the employment share in industry as a control variable. Unfortunately, the measure of the local industry structure is available for only 51 cities across three waves. Still, our main effect of interest is in fact even larger in this specification, whereas the share of workers in industry does not enter significantly in predicting church attendance. The same is true for the share of workers in services, which is added in column 2. Alternatively, when we combine industry and services to control for the employment share in modern (non-agricultural) sectors in one variable (column 3), qualitative results are also effectively the same. Thus, our results do not seem to be driven by changes in industry structure as a potentially confounding development.

To directly address potential city-specific differences in the introduction of welfare measures, column 4 adds a city-level measure of social welfare spending, namely public per-capita expenditures on poor relief, that is widely available across cities and time. Again, city-specific changes in these welfare expenditures do not predict changes in church attendance, and the main result on the effect of education remains qualitatively unaffected. This supports the interpretation that city-specific affectedness or implementation of welfare-state measures are unlikely to be major confounding factors.

Activities in secular associations might have increasingly crowded out participation in church activities during our period of observation. To address this, we use the vote share for social-democratic parties in national elections over time as a proxy for the strength of alternative secular movements. August Bebel, one of the leading figures of social democracy in Germany at the time, famously declared that “Christianity and Socialism are opposing each other like fire and water.”Footnote 26 Emerging secular movements might have organized activities in particular on Sundays that would have taken time away for possible church visits, and they might have offered facilities that were traditionally in the realm of the church. To the extent that the social-democratic party organized activities in Sunday and that members of other emerging secular movements were more likely to vote for the social-democratic party, controlling for the social-democratic vote share will capture aspects of the emerging secular movements. In addition, in its founding constitution of 1875, the German social-democratic party explicitly demanded that religion should become a private affair outside the realm of the state. In the extended specification including the social-democratic vote share, results on our main coefficient of interest are unaltered and the vote share for social-democratic parties is itself statistically insignificant (column 5). The same qualitative results are obtained when controlling for the vote share of all left-leaning parties (not shown).

Another possible concern is that the expansion of education might have been used by the state to influence the population to support the emerging nation (e.g., Lott Jr 1990; Pritchett and Viarengo 2015), which might have antagonized it against religious organizations. While this would most directly relate to primary schools and less to the advanced schools of our analysis, we address this concern by adding the vote share for nationalistic parties to our model. The nationalistic parties were explicitly singled out by Bismarck as supporting the German state, so that their vote share provides a decent proxy for the formation of a nation-minded population (Cinnirella and Schueler 2016). As is evident from column 6, changes in the share of votes for nationalistic parties are not significantly related to changes in church attendance, and their inclusion does not qualitatively affect our estimate of the relationship between education and church attendance.

6.3 Subsample analyses

Results also prove highly robust in different subsamples. As the first column of Table 10 in the Appendix shows, results are qualitatively unaffected in the sample of the 25 cities that were already observed in 1890 (statistical significance at 11%). Results are also robust when dropping the 32 observations whose church attendance data were imputed by linear interpolation (column 2). We further test the robustness of our results to discrepancies in the number of Protestants between the church district and the city in 1910 (the only year for which both measures are available). In a subsample of cities whose size was close to that of the church district, the education coefficient remains qualitatively unchanged (column 3).

Over time, new advanced schools may have been set up in medium-sized cities in the neighborhood of the large cities included in our sample, pulling students from medium-city cities out of advanced schools in the large cities where they had previously attended.Footnote 27 To test that results are not driven by such changes, we exclude all cities situated in urban regions, restricting the analysis to only those cities situated in rural regions or regions with rudiments of suburbanization (Regionen mit Verstädterungsansätzen).Footnote 28 Our results hold in this subsample (column 4).

When we split the sample along the share of Protestants in the city in the census year 1910 (columns 5–8), we find that the result is largely the same in cities with a Protestant majority and minority. In cities that are overwhelmingly Protestant, the coefficient is still negative and large, but loses statistical significance. This may reflect the reduced sample size, but it may also indicate that determinants of demand decreases like education play a lesser role in cities with a very large Protestant share because social pressure motives make it more common that people attend church as an investment in social capital (Hölscher 2005).

Results are also robust to a number of additional robustness checks not shown in the table. First, they are robust to dropping Berlin, by far the largest city in the sample. Second, we included dummy variables for structural breaks in municipal borders, such as when smaller neighboring towns were incorporated into Berlin before the 1925 observation and into several cities in the Ruhr area before 1930. Qualitative results are unaffected in this specification. Third, to test that results are not driven by jumps due to measurement error in the data, we included dummy variables for periods whenever particularly large changes occurred in the variable of interest between two points in time, such as upward or downward jumps of 50, 30%, or even only 20%. Results are fully robust, and if anything, point estimates become larger, as would be expected for classical measurement error.

6.4 Different measures of income

Given that income is often a main competing explanatory factor for decreasing church attendance in secularization theories (see Sect. 2.1) and given that income and education are often positively associated, we also focus on the robustness of our results on the effect of education on church attendance to the use of different income measures. The proxy for income included in our baseline model refers to the per-capita municipal tax revenue of cities, available from the same Statistical Yearbooks of German Cities that provide our data on enrollment in advanced schools. While overall municipal taxes proxy for a city’s income, they may to some extent also reflect specific local preferences in that, for example, some cities charged a horse tax while others did not.

By contrast, there is one component of municipal taxes, the income tax, that was centrally determined and was directly based on the income of the population. However, city-level data on per-capita revenues from income tax are available only for Prussian cities and only for the period 1890–1905. A third proxy for overall income used previously in Becker and Woessmann (2009, 2013) is the average annual income of male elementary-school teachers. As teacher income was almost entirely financed from local contributions, it likely reflects overall local income, and teaching is a well-defined occupation that facilitates comparison. However, teacher income data are only available at the county (rather than city) level and again are only available for Prussia and only for the period 1890–1910.

As shown in Table 11 in the Appendix, all three income measures are positively associated with enrollment in advanced schools. However, only the two alternative measures capture statistical significance, whereas the original municipal tax measure does not. Furthermore, in this depiction that includes city and year fixed effects so as to reflect the identifying variation of our analysis, changes in both tax-based measures are significantly positively associated with changes in the teacher income measure (although not among each other), corroborating the interpretation that each proxies for income.Footnote 29

In our baseline model, municipal income tax per capita consistently enters insignificantly in predicting church attendance. To test whether the specifics of this measure drive our insignificant results on income, columns 2 and 3 of Table 5 show results when instead using the two alternative income measures. Both income tax per capita and teacher income enter the model statistically insignificantly and negatively. Despite the smaller samples of available income data, the coefficient on the education measure remains significant and is in fact larger in magnitude than in the baseline model. When including all three income measures together, all three have a negative but insignificant relationship with church attendance (column 4). Even in the absence of the education variable (columns 5–7), neither of the income measure captures statistical significance in predicting church attendance.

In sum, the choice of the income proxy is not driving our results. All income measures are insignificantly related to church attendance in our preferred specification. What is more, irrespective of the income proxy used, the negative effect of education on church attendance is large and highly significant.

In light of the conceptual framework discussed in Sect. 2.1, our results suggest that in our historical context, modernization in the form of higher education was a stronger driver for the decline of church attendance than other aspects of modernization. The Marxian view that improved material conditions lead to lower church attendance is not supported by our city-level analysis (see also Becker and Woessmann 2013). Also, an opportunity-cost view of modernization where larger cities are associated with more temptations to spend a Sunday does not come out in the regression analyses. Instead, increased education matters. We will discuss potential mechanisms by which education affects church attendance in Sect. 9, where we exploit data on different types of advanced schools.

7 Dynamic panel models

The fixed effects panel models so far have only considered contemporaneous effects of education on church attendance. In this section, we turn to dynamic panel models that consider different lags of the education variable, include lagged church attendance, and test for robustness to city-specific trends.

7.1 Different lag structures of education

A first concern is that results so far might suffer from bias due to reverse causality if religious participation affects education decisions. Furthermore, we interpret our measure of education—enrollment in advanced schools—as a measure of the overall educational and scientific orientation of the city as reflected in families’ openness to advanced education. Given this measure, one might expect education to affect religious participation with some time lag. In particular, part of the effect may come from the students who went to advanced schools subsequently deciding to reduce religious participation themselves.

The first two columns of Table 6 add the first lag of enrollment in advanced schools to our baseline model. Both the contemporaneous and the lagged enrollment variable enter the model with negative coefficients, but the coefficient on the lagged variable is about twice as large in absolute terms and is the only one capturing statistical significance. Even more strikingly, when adding the second lag of advanced-school enrollment, both the contemporaneous and the first lag of the education measure are insignificantly different from zero, while the second lag is negative, large, and statistically highly significant (columns 3–4). Alternatively, when including each lag of the education variable separately, both the first and the second lag enter significantly with a coefficient estimate slightly larger than in the contemporaneous baseline model, but the model with the second lag is most precise (columns 5–6). By contrast, the third lag of the education measure (or any further lag) does not capture statistical significance (column 7).

The results of the models with alternative lag structures indicate that increased enrollment in advanced schools is followed by subsequent decreases in church attendance. The fact that the dynamic pattern is strongest after about 10 years (the second lag) is hard to reconcile with an interpretation where the results are mostly driven by reverse causality from church attendance to advanced-school enrollment. Instead, it is most consistent with an interpretation where the effect of advanced education on religious participation materializes over time.

The interpretation is corroborated by the fact that lagged church attendance does not predict subsequent changes in advanced-school enrollment. In a model where the enrollment rate in advanced school is the dependent variable, lagged church attendance does not enter significantly (column 8). This is true for additional lags of church attendance, as well (not shown). That is, while changes in education predict subsequent changes in religious participation in our model, the reverse of changes in religious participation predicting subsequent changes in education is not true.

7.2 Lagged dependent variable and city-specific trends

A further concern with the panel models presented so far is that religious participation is likely correlated over time. To account for persistence in church attendance, Table 7 presents dynamic panel models with a lagged dependent variable. When added to our baseline model in column 1, current church attendance is indeed significantly positively related to lagged church attendance.Footnote 30 At the same time, the coefficient on advanced-school enrollment remains significantly negative. The long-run effect of advanced-school enrollment on church attendance implied in this model (the coefficient on enrollment over the difference between one and the coefficient on lagged church attendance) is −2.513, which is even larger than the −1.866 in the static baseline panel model.

Interestingly, when we use the second lag of advanced-school enrollment (rather than current enrollment), lagged church attendance becomes insignificant (column 2). This suggests that the persistence in church attendance really mainly reflects that lagged church attendance is affected by longer lags in (persistent) advanced-school enrollment. As in the model without a lagged dependent variable, only the second lag of education enters significantly when contemporaneous education and two lags of education are entered jointly (column 3). The contemporaneous education variable is also strongly negative but does not reach statistical significance at conventional levels (with or without the first lag included, column 4). Overall, results are thus very robust to the inclusion of the lagged dependent variable.

Our panel fixed effects models identify the coefficient of interest from within-city changes in education and church attendance over time. The identifying assumption of these models is that the change (rather than level) in church attendance would be similar across cities in the absence of differential changes in advanced-school enrollment (conditional on other observed changes). However, cities may be on different long-term trends in church attendance for other reasons unobserved in the analysis. One way to account for potential bias from different long-term city trends is to add city-specific linear time trends to the model, that is, to interact each city fixed effect with a time trend. Such a specification is very demanding, as it may throw out much of the unbiased identifying variation from the analysis. Still, when we add city-specific trends to the basic dynamic panel model in column 5 of Table 7, the negative coefficient on advanced-school enrollment stays significant and even increases in size.

8 Instrumental-variable estimates

The panel models attempt to purge the coefficient of interest from potential bias from omitted city characteristics by including city fixed effects. However, none of the specifications so far attempts to directly model variation in school enrollment that is arguably exogenous to the error term of our church-attendance model. A main remaining concern is that the identifying variation in school enrollment might be driven by variation in the demand for advanced schools that stems from omitted variables that are also associated with religious participation.

In this section, we propose an instrumental-variable model to identify arguably exogenous variation in advanced-school enrollment. An instrumental variable that can identify variation in advanced-school enrollment that is not driven by individual preferences for advanced schooling is the supply of advanced schools, as measured by the number of advanced schools in a city. In such an instrumental-variable model, only the part of the within-city variation in advanced-school enrollment that stems from the opening and closing of advanced schools is used to identify the effect of advanced schooling on church attendance. The number of advanced schools in a city affects the enrollment rate because a larger number of schools ceteris paribus decreases commuting time to school and offers more possibilities to parents to send their children to advanced schools. At the same time, the number of advanced schools should not be related to church attendance in other ways than through the actual enrollment in school, so the exclusion restriction is likely to hold. Note that we keep the fixed effects panel structure of the model, so that results are identified from differential within-city variation in the opening and closing of advanced schools over time.

In the first stage of this instrumental-variable model, the number of advanced schools in a city significantly predicts advanced-school enrollment (Table 8). In column 1, we use the first lags of the number and enrollment in advanced schools, whereas in column 2 we use the second lags; results are quite similar. The partial F statistics of the excluded instrument in the first stage suggest that the instruments are not particularly strong, though.

In the second stage, the point estimate on advanced-school enrollment is slightly larger than and insignificantly different from our baseline model, even though it does not capture statistical significance at conventional levels. To elaborate on these results, we also look at the enrollment rate just in Gymnasien and Realgymnasien, the more classical institutions of the advanced-school system (see Sect. 3.2), as we discuss in greater detail in the next section. Here, we use the number of Gymnasien and Realgymnasien as an instrument. The first-stage partial F statistics are slightly larger in this specification (columns 3 and 4), although still not particularly strong. The estimated impacts of advanced-school enrollment in the second state are larger than in our main specification and reach statistical significance at the 10% level.

While statistical precision is limited in these instrumental-variable estimations, in the absence of other instruments that plausibly meet the exclusion restriction we still find these instrumental-variable results interesting and supportive of our findings. Overall, even though the estimates have large standard errors, the point estimates are consistent with and even larger in magnitude than the baseline results, indicating that advanced education reduced church attendance.

9 Explorations into mechanisms: different types of advanced schools

As a final analysis, we explore different potential mechanisms how education may have affected religious participation. While education may have affected economic development which some secularization hypotheses argue to affect secularization (Sect. 2.1), the fact that we do not find evidence for effects of different measures of income and urbanization in our models (Sect. 6.4) casts doubt that this is a particularly relevant mechanism in our context. Similarly, our analysis of robustness to contemporaneous changes in other factors in Sect. 6.2 has shown that the estimated effect of education is hardly affected by conditioning on enrollment at the university level, the sectorial structure of the economy, welfare spending on poor relief, the emergence of secular movements (as measured by social-democratic votes), and nationalistic sentiment (as measured by votes for nationalistic parties). While each of these factors might in principle be conceived as a potential mechanism through which education might have affected religious participation, the results suggest that none of the factors is a major channel of our main result. These results suggest that it might have been the schooling per se that exerted the effect.

As discussed in the conceptual framework (Sect. 2.1), there may be two separate aspects of schooling that might have given rise to reduced church attendance, which we referred to as critical thinking and scientific knowledge. We can use the different curricula of the different types of advanced schools (see Sect. 3.2) for an exploration into which of these two mechanisms may have been particularly relevant. The school type most directly oriented towards scientific knowledge was the newly emerging Oberrealschule with its curricular focus on the natural sciences. In these schools, students learn scientific facts that may reduce their belief in religious explanations of natural phenomena. By contrast, the traditional Gymnasium had a humanistic curriculum focused on classical languages and literature which may have sparked critical thinking towards the church as an institution in general but instilled only limited knowledge in modern sciences. To a lesser extent, the same can be argued for the Realgymnasium with its curricular focus on modern languages.

Table 9 shows estimates of our model separately for each type of advanced schools. The first column indicates that the significant negative effect of total advanced-school enrollment on church attendance is also visible in the subsample of periods for which data on attendance rates are available by type of advanced schools. Column 2 separates out the advanced schools for male students (Höhere allgemeine Bildungsanstalten für das männliche Geschlecht) and the advanced schools for female students (Höhere Mädchenschulen). The subdivision into different types of advanced schools is only available for the schools for male students. In fact, the Höhere Mädchenschulen were neither oriented towards the humanistic education of the Gymnasien nor towards the advanced teaching in the natural sciences of the Oberrealschulen but were rather attended by the daughters of upper-class families (“höhere” Töchter, see Konrad 2012, p. 85). Consistently, the point estimate for female schools is only half as large as for the male schools, although both lack statistical significance when entered jointly. Column 3 jointly enters the enrollment rates in the different types of advanced schools, whereas columns 4–7 show results for each of the main types of advanced schools separately.

While the separate estimates of the different school types are all relatively imprecisely estimated, they all have negative point estimates and fall roughly in the same ballpark, with no clear indication that the effect of one school type is particularly stronger than the other. If anything, the effect seems to be largest in the classical institution of the Gymnasium (and possibly the Realgymnasium in column 3) which had limited teaching in the natural sciences. As a consequence, it does not seem that the instillation of scientific knowledge is a pivotal aspect for the effect of advanced-school education on church attendance. Rather, the evidence on the Gymnasien suggests that a general conveyance of critical thinking in advanced schools may have undermined the willingness to subordinate to the institutionalized church.

This is consistent with the result on enrollment in middle schools (Realschulen), which is also included in column 3. The coefficient on middle schools, which ran for nine rather than 12 years and had a practically oriented rather than academic curriculum focused on occupational demands (Konrad 2012, [p. 82]), is small and positive. Finally, when combining enrollment in the three main types of advanced schools together in column 8, the negative effect is in fact statistically significant and larger than the overall effect, indicating a rather general effect of these advanced schools.

Of course, these results are in no way conclusive, not least given the limited statistical power of the separate estimates. However, they inform the debate about which aspect of education is particularly relevant in decreasing religious participation. Our results side with the explanation that education decreases the belief in the institution of the church, while we find little evidence that the main channel is the learning of scientific facts.

10 Conclusion