Abstract

This study describes the socio-cognitive dynamics of collaborative online knowledge-building discourse among Dutch Master of Education students from the perspective of openness. A socio-cognitive openness framework consisting of four social and four cognitive components was used to analyze contributions to online collective knowledge building processes in two Knowledge Forum® databases. Analysis revealed that the contributions express a moderate level of openness, with higher social than cognitive openness. Three cognitive indicators of openness were positively associated with follow-up, while the social indicators of openness appeared to have no bearings on follow-up. Findings also suggested that teachers’ contributions were more social in nature and had less follow-up compared to students’ contributions. From the perspective of openness, the discourse acts of building knowledge and expressing uncertainty appear to be key in keeping knowledge building discourse going, in particular through linking new knowledge claims to previous claims and simultaneously inviting others to refine the contributed claim.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In higher education, there is increasing interest in collaborative learning and knowledge building (within) communities (Garrison et al. 2010; Love 2012). Knowledge building in educational settings is conceptually comparable to knowledge creation in innovative organizations, but involves not only generating new ideas, but also the further development of ideas within the community (Bereiter and Scardamalia 2014). Community knowledge creation is seen as beneficial in helping students develop ways of thinking and the skills necessary to flexibly adapt to changes in our society, and also to develop ideas and insights as a basis for innovation (Paavola and Hakkarainen 2005). Online collaboration tools are widely accepted and integrated in educational practices to facilitate computer supported collaborative learning (CSCL) and online knowledge building. Knowledge building communities vary in size and scope: collaboration can be limited to fixed, small groups that work on different subjects, but building knowledge collaboratively can also be the responsibility of an entire community in which varying combinations of groups engage in a continuous, dynamic collaboration process (Zhang et al. 2009).

Knowledge creation is viewed as a social process among innovative communities in the pursuit of new knowledge which is built by the members of a community in interaction with each other through shared objects (Paavola et al. 2004; Stahl 2012). According to van Aalst (2009), knowledge creation is the mode of discourse representing a higher level of intellectual effort by community members than knowledge sharing (i.e., merely presenting pieces of knowledge) or knowledge construction (i.e. bringing together established knowledge in the domain). At one level, knowledge creation involves the development of shared objects needed to create new knowledge (i.e., ideas, theories, explanations, and justifications), while at another level it evaluates the knowledge advances and social issues in the community.

The socio-cognitive nature of community knowledge building

In CSCL research, the term community is often taken for granted (Barab 2003; Wise and Schwarz 2017), which complicates the distinction between a group of collaborating learners and a knowledge building community. This study uses five features of a knowledge building community, based on previously reported characteristics of a knowledge building community (Hong and Sullivan 2009; Scardamalia and Bereiter 2006; Zhang et al. 2009) and of a community of practice (Barab 2003; Barab and Duffy 2000). First, a knowledge building community is characterised by the orientation towards knowledge development as a collective effort. Second, a knowledge building community is recognised by discourse in which understanding emerges from the collective practice of idea development using authoritative sources originating from outside the community. Third, the discourse is facilitated by an environment which is appropriate for community knowledge building. Fourth, a community culture (i.e. common goals, meanings and practices) emerges as a result of social negotiation as the community develops. Last, a sense of purpose and awareness of self will gradually develop at both the individual and the community level. Whether or not a group of learners evolves into a community will eventually become evident in the knowledge building process. Barab (2003) for instance has noted that “one cannot simply design community for another, but rather community is something that must evolve with a group around their particular needs and for purposes that they value as meaningful” (p.199).

Building knowledge as a community requires more than the division of labor between community members working on a task. Collaboration in knowledge building is a complex activity, aiming at the collective improvement of ideas in a process of socio-cognitive collaboration. Cress and Kimmerle (2008), for instance, state that in collaborative knowledge building, “social systems depend on cognitive systems, because there would be no communication without cognitions” (p. 109). They argue that the social and cognitive systems involved in collaborative knowledge building operate separately, but are also interconnected in that they influence each other and develop together into more complex systems over time. Scardamalia (2002) addresses both aspects of collaborative knowledge building in a system of twelve principles describing the socio-cognitive dynamics of knowledge building, departing from the viewpoint that every member’s idea is valuable and that the community will evaluate these ideas and generate new insights through discourse, with the constructive use of authoritative sources. As a result, creative solutions will be generated for the community’s self-defined problems. This implies that community members should adopt a “design thinking mindset” (Bereiter and Scardamalia 2014), in which taking knowledge for granted is replaced by a joint effort to critically question established knowledge, adopt an open attitude towards new ideas and reach a thorough understanding by the meaning-making process which evolves in the discourse (de Jong 2015). The interrelatedness of social and cognitive aspects of knowledge construction processes is reflected in the discourse of the community, so the analysis of contributions to such discourse aids the mapping of the socio-cognitive dynamics of online knowledge building (Howley et al. 2011).

Factors that influence online knowledge building discourse

Online knowledge building conversations vary greatly in the level of discourse and the associated knowledge yield, ranging from mere fact-oriented knowledge sharing, to more elaborative understanding in knowledge construction and eventually to knowledge creation, in which continuous elaboration results in idea improvement. Discourse patterns reflecting the lowest level of knowledge sharing are observed much more frequently than patterns reflecting the higher level modes (Fu et al. 2016; van Aalst 2009). This indicates that realizing a thorough and effective knowledge building discourse is a demanding joint practice which cannot be taken for granted.

Sustainable online interaction and participation are crucial for knowledge building. Limited participation and fragmented conversations make the construction of collective knowledge virtually impossible. Previous studies have reported several factors influencing participation and continuation, amongst which are the organization and facilitation of courses, characteristics of participants, and the discourse itself. For example, Cacciamani et al. (2012) found that higher participation is associated with a more critical evaluation of the knowledge itself and of the knowledge-building activities in the community. Beneficial for participation are a clear organization and facilitation of the discourse (Dennen 2005), with clear expectations about participation. In addition, students must consider the knowledge subjects as relevant, and feel free to bring in different perspectives (Cacciamani et al. 2012). Goal orientation also makes a difference: someone who wants to learn from the discourse participates differently than someone who wants to make minimal effort, or is mainly focused on receiving appreciation from others (Wise et al. 2012). Student participation also benefits from teacher presence characterized by their providing feedback without taking over the conversation (Dennen 2005). Too little or too much teacher participation was found to have a negative impact on student participation (Schrire 2006; Zingaro and Oztok 2012), indicating that teachers should dose their contributions carefully. Nevertheless, the degree of participation in online knowledge building communities has repeatedly been reported as disappointing.

One cause of limited participation may be that follow-up participation lags behind, causing conversations to cease prematurely. Online contributions often do not receive follow-up, for example due to participant characteristics such as the role of the contributor. Several studies indicated that students who are perceived as active or are considered intelligent, tend to receive more follow-up (Ke et al. 2011; Zingaro and Oztok 2012). Ioannou et al. (2014) have suggested that the absence of indications referring to one’s own beliefs, opinions and reference to sources jeopardize knowledge construction, as readers do not find textual clues to build on. A study by Jeong (2006) found that aspects of conversational language in computer-supported collaboration (e.g. posing questions, agreement, apology, gratitude, humor, using a signature, greeting) lead overall to more follow-up. Jeong suggested that conversational language may be found more personable and express more openness to differing viewpoints, which might encourage readers to respond more easily than in contributions without signs of conversational language. The present study aims at taking these suggestions a step further and is based on the assumption that the characteristics of the online contributions to discourse itself might be understood as different manifestations of socio-cognitive openness that encourage the continuation of a conversation. This study therefore explores how social and cognitive openness are manifested in online contributions in two separate student cohorts operating as knowledge building communities in differently organized consecutive courses that were facilitated by different teachers and investigates how manifested openness relates to the continuation of their conversations.

Socio-cognitive openness as a characteristic of community knowledge building discourse

The work of a knowledge building community is intentional and primarily benefits the community itself (Scardamalia and Bereiter 2010). In knowledge building communities working with the assumptions of intentionality and community benefit, openness is key (Chinn et al. 2011; Song 2017), reflecting the willingness to think together. In this study, the term openness pertains to the cognitive, epistemic, and relational activities of community members as manifested in their discourse. To build knowledge as a community, members must cognitively engage with each other in an intellectual process of developing knowledge claims. This implies intellectual efforts such as developing, comparing, and judging claims. It also implies taking a critical and flexible epistemic stance in order to evaluate knowledge claims and develop alternative viewpoints. In addition, openness has a social dimension. Practicing the relational skills inherent in opening up to others fosters a climate of freedom to contribute immature knowledge claims (Ness and Riese 2015). Relational skills are a prerequisite to becoming truly engaged with other community members, which in turn supports the ability to think along with each other. (Song 2017). This study therefore takes as its departure point the assumption that openness is a necessary condition for understanding one another during online knowledge building and aids the development of new insights as a joint effort. We also assume that it involves both social and cognitive aspects, and that it can be expressed in different ways. The next section presents a conceptual framework to analyze socio-cognitive openness in online discourse.

The conceptual framework for socio-cognitive openness

Departing from the observations above, a conceptual framework was developed to enable a systematic analysis of online contributions to collective knowledge building. The framework is composed of eight different components which serve to detect openness. The selection of components to be included in the framework is grounded in a dialogical approach to learning and knowledge building (Ludvigsen and Mørch 2010). The dialogical approach views the construction of knowledge as an intermental process, where new insights emerge from a multivocal dialogue encompassing multiple perspectives (Koschmann 1999; Wegerif et al. 2010).

In compliance with the dialogical approach, the current study presumes two key principles to knowledge building: a) knowledge building starts with producing knowledge claims and b) taking an intersubjective stance is of vital importance to develop new insights in response to these claims. Producing knowledge claims takes place when an individual brings in a proposition on a relevant subject or asks a question with the aim of being able to bring in a new proposition. Concomitantly, community members engage in intersubjective stance taking (see du Bois 2007; Hyland 2005; Kärkkäinen 2006; Martin and White 2003). Following du Bois, an intersubjective stance is viewed as a public dialogical act consisting of three simultaneous activities: Evaluating knowledge claims, positioning the self, and aligning with the other(s). The intersubjective stance relies on the principle of multivocality, which implies acceptance of the multifaceted character of conversations, where different voices can co-exist without necessarily reaching consensus ((Skidmore and Murakami 2012; Suthers et al. 2013).

The components that have been brought together in the framework reflect these basic principles and were first grouped on the basis of their cognitive or social character. The components have a descriptive character; they refer to the ways in which openness can be expressed in online contributions. The cognitive dimension contains components that primarily relate to the mental activities of producing and evaluating knowledge claims. These activities entail connecting knowledge to earlier contributions (Gweon et al. 2013; Weinberger and Fischer 2006), justifying knowledge claims, (Baehr 2015; Chinn et al. 2011), taking epistemic stance (Chinn et al. 2011; Howley et al. 2013) and inviting response (Goodman et al. 2005; Martin and White 2003). The social dimension contains components mainly relating to how the contributor aligns with others and presents him- or herself. These components relate to the transactivity of knowledge between self and another (Gweon et al. 2013; Mitchell and Nicholas 2006), the ownership of problems (Ligorio et al. 2013; Loperfido et al. 2014), personal positioning towards the claim (Martin and White 2003; Rourke et al. 2001) and the authority position that is taken by the contributor (Howley et al. 2011; Howley et al. 2013). The background, development and content of the framework are described in more detail in van Heijst et al. (2019).

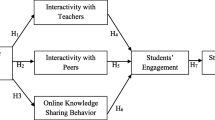

In a second step of building the socio-cognitive openness framework, discourse acts were articulated as an intermediate category between the components and the social and cognitive dimensions of the framework. The components were grouped in pairs on the basis of their resemblance relative to the above stated key principles of knowledge building producing knowledge claims and taking intersubjective stance. When engaged in the discourse acts of building knowledge, expression of uncertainty, community orientation and the expression of self the interactants are actually doing things with regard to the discourse as they express social and cognitive openness in the collective knowledge building process. Building knowledge reflects the principle of producing knowledge claims, while the expression of uncertainty, community orientation and the expression of self are reflecting the activities necessary to accomplish the principle of intersubjective stance taking. The final framework for the analysis of openness thus represents three levels of openness: dimensions, discourse acts and components (see Fig. 1).

Thus far, there is no clear insight into the expression of openness in online knowledge building, nor into its association with context characteristics such as community, participant roles, or trimester characteristics (temporality, course characteristics), nor how openness under the different context characteristics impacts on the continuation of conversations. The objective of the present exploratory study is therefore to investigate the presence and impact of socio-cognitive openness in the online knowledge building discourse of two knowledge building communities in a Master’s program. The research questions guiding the study are: (1) How do social and cognitive openness manifest themselves in online contributions? (2) How do social and cognitive openness relate to follow-up? (3) How do context characteristics relate to socio-cognitive openness and follow-up?

Method

Context

The study took place in the context of a nationally top-rated Master’s Program in Education Learning and Innovating (M. Ed.) at a Dutch university of applied sciences and teacher education. The two-year part-time program is based on knowledge building pedagogy which focuses on collective knowledge creation (de Jong 2015) and includes study activities supporting students’ work on an innovation in their workplaces. The practice-based research they conduct during the program is supportive of the decisions they make in their innovative work practices. Students are experienced professionals who aspire to become innovators of learning and development in their work place. The Master’s program emphasizes the joint development of knowledge in a knowledge building community of students and teachers which lasts throughout the program. To support the work-related processes during the program, five trimester courses are designed around four monthly one-day meetings at the institute. The two cohorts of students selected for the present research (n = 37; n = 32) participated in three trimester courses scheduled one after the other in the first academic year. The three courses, labeled “Innovating in Teams”, “Learning” and “Design for Learning” focused on investigating how innovations can be developed effectively at the team level, deciding which vision for learning is appropriate for the innovation, and designing an intervention to support the innovation. The consecutive courses differed with regard to the assignments. There were also differences with regard to the organization and facilitation of the online discourse, based on personal style of the teacher and the characteristics of the course. The overall aim of the three courses, was to collectively work on the improvement of students’ conceptual ideas about the course subjects, using scientific and practical knowledge and using each other’s perceptions and experiences to create a community knowledge base for the benefit of all. Each course ended with the writing of a term paper, either individual, as a sub-group, or as a combination of individual and collective tasks. Regardless of the degree of collective work included in the assignment, students were encouraged to build knowledge collectively throughout the program. Although there were slight differences between the courses of the two cohorts, the pedagogy and the facilitating teachers were the same.

Participants

The study included 61 students (44 females, 17 males), all of whom were experienced professionals participating in the part-time Master’s program to become more proficient in initiating and steering innovations in their working practices. A minimum of two years of work experience is required to enroll. The majority (n = 52; 85.3%) were in the teaching profession, nine (14.7%) were knowledge professionals (e.g., human resource development professionals, educational consultants, director of a consulting company). The average age was 44.5 years (SD = 9.4; range 23–59 years). Contributions from seven teachers, (five females, two males; mean age 42.4 years (SD = 8.1; range 31–56 year) who participated in the selected conversations, were included in the data. All teachers had at least three years of experience in the Master’s program and in the use of Knowledge Forum. Five teachers (including the first author) were course teachers, while two additional teachers were study coaches who joined the conversations.

Procedure

The data were taken from a database containing the online discourse of students and their teachers. To facilitate collective knowledge building between the course meetings, Knowledge Forum® (KF) was used. KF is designed to facilitate collective construction of knowledge and a well-developed understanding of issues which arise in the community (Scardamalia 2002). In KF, collaboration spaces (KF views) were created by the course teachers as an integral part of the course design. In addition, students were allowed to create their own collaboration spaces. In the collaboration spaces, students build knowledge related to the course subjects, starting from questions and ideas which arise from the activities they undertook as innovators in the work place. Building knowledge in KF was done by placing contributions (KF notes). A note could either be a conversation starter, which initiates a new conversation thread, or a build-on note, which connects to a previous one. KF also provides the feature of a rise-above note, in which previous notes can be collapsed and a new conversation can be started based on insights of the previous conversation. Figure 2 shows a screen shot of a KF view included in this study.

Students and teachers were informed about the study before the start of the program and agreed to participate in the study. Selection of data and data analysis took place after completion of the courses and the associated formal assessment of the assignments. The procedures were approved by the Open University research ethics committee.

Instrument

Based on the conceptual framework (van Heijst et al. 2019), a coding scheme (see Table 1) and coding instruction were developed through an iterative process involving three coders who were familiar with the program and KF. The first and second author developed the coding procedure and applied it to data which was not involved in the study. Then, in three stages of coding, discussing differences and refining of the coding manual and instructions, 20% (n = 119) of the KF notes were subjected to the coding procedure to establish sufficient reliability. The first author and a third coder independently coded 10% (n = 59) and reached almost full agreement in discussing the results while refining the manual. Next, the first author coded another 10% (n = 60) of the data and recoded them after approximately three months. Finally, six KF notes that remained under discussion were, together with their adjacent notes, once again coded by an external coder who was unfamiliar with the educational and research context and not involved in the development of the instrument. Comparison of the coding of the first author and the external coder yielded satisfactory intercoder reliability (Kcognitive openness = .94; KCk = 1.00; KJkc = 1.00; KEs = .78; KIr = 1.00; Ksocial openness = .89, KT = 1.00; KO = .89; KPtc = .77; KA = .68, n = 19). The first author coded the remainder of the data.

Data collection

For the study, 638 notes written by 68 community members were selected from 10 KF views. These notes covered a representative image of the students’ activities over the two cohorts and the three courses. Five KF views were full community views (i.e., collaboration spaces per cohort for all participating students and their teachers) and five others were created for further exploration of issues of sub-communities within the cohorts. The full community views were initiated by the course teachers. These views were initiated at the start of the courses and dealt with collaboration tasks aiming at knowledge construction based on prescribed knowledge sources, exploring each other’s work contexts and understanding the courses’ knowledge base. The sub community views were mostly initiated by students and dealt with a further exploration of a chosen theory or perspective. Here the aims were to develop a knowledge base to be applied to students’ own practices. Some views included sub community collaboration tasks to be assessed as part of their individual term papers. The sample contained notes of extensive conversation threads containing at least three notes (n = 64), as well as isolated notes, which were not connected (n = 56) or were merely connected to one note (n = 33). All notes within the selected conversation threads were included in the analysis, including both students’ and teachers’ notes.

Data analysis

The qualitative and quantitative analysis of the KF contributions consisted of five consecutive steps, outlined as follows:

-

1)

Determination of appropriate level of analysis

-

Individual contributions were used as primary data. As many contributions build on previous ones, texts of the surrounding contributions in the same conversations were taken into account in the coding decisions, allowing for analysis of all contributions, whether they stood alone or were part of a conversation between community members.

-

2)

Determination of unit of analysis

-

The unsegmented KF note was considered appropriate, as the aim of the study was to determine the degree of openness and the interrelatedness of different kinds of openness within contributions.

-

KF notes were regarded as single segments with natural borders, signaling the contribution to knowledge of an individual at a particular point in time (Clarà and Mauri 2010; Strijbos et al. 2006).

-

For the sake of consistency, four KF notes in the sample had to be segmented. The coders agreed that these notes elaborated on two distinct topics, which should have been discussed in separate notes.

-

3)

Preparation and qualitative analysis of data

-

KF notes were extracted from the KF databases, anonymized, marked for participant number, time of creation and thread structure information, and entered into ATLAS.ti® Qualitative Data Analysis software for coding.

-

Together with the coding function of the software, comments and analytic and theoretical memo functions were used, guaranteeing constant comparison during coding (Friese 2014).

-

The socio-cognitive openness of each KF note was analyzed for the eight components of the coding scheme in the ATLAS.ti® project database. For each component codes were created which indicated signs of openness. These were attached to selected text fragments in which linguistic markers of openness were found. If no signs of openness for a component were found in the note, it was coded as not-open for this component. In sum, 642 units were analyzed. 48 notes were excluded from the analysis, due to lack of content or off-task character (i.e., not related to the knowledge subject).

-

4)

Entry of coding results into IBM SPSS version 24.0 for quantitative analysis

-

SPSS-variables were created for the components and defined as 1 when the KF note showed manifest openness or as 0 in case no signs of openness were observed.

-

Descriptive statistics were applied to investigate the frequencies of the occurrence of openness and mean scores for the social and cognitive dimension.

-

Principal Components Analysis for Categorical Data (CATPCA) was then carried out to examine whether the relatedness of components in the conceptual framework was reflected in the data.

-

5)

Measurement of relationship between follow-up and level of social and cognitive openness

-

Using McNemar’s test, the level of social and cognitive openness was compared to community type (i.e., was the KF note located in a full community or in a sub community view) and teacher-student role. Using Chi-square tests, the level of social and cognitive openness was compared to trimester (entailing potential differences such as character of the course subjects, assignment, teacher style, student enculturation or community development).

-

McNemar’s test compared openness per component to the presence of follow-up notes.

The authors are aware that, due to the nature of the data, the CATPCA and chi-square tests violate the statistical independence assumption. To account for the interdependence of the data, McNemar’s test was used for comparisons where possible. Nevertheless, the results should be interpreted cautiously.

Results

This section presents the results in two parts. First, findings concerning the question as to how social and cognitive openness manifest themselves are presented. In this part, two full text examples of the analysis of KF notes are presented to explain how socio-cognitive openness occurs in the contributions. In addition, the interrelatedness of the components, the average sum scores for the social and cognitive dimensions and frequency counts for the components of social and cognitive openness are presented. Second, findings are presented concerning the question of how the level of social and cognitive openness relates to follow-up contributions. The answers to both questions are described in terms of the levels of social and cognitive dimensions as well as the eight components and the four discourse acts, and are differentiated for community type, trimester, and teacher-student role.

The manifestation of socio-cognitive openness

As an illustration of how socio-cognitive openness emerged in the conversations, the qualitative analysis results of two typical and contrasting KF notes are presented. The notes were posted in a 15-note conversation amongst five students. The conversation was situated in the context of a Learning course and started with a note about the character of modern educational processes, where communities of students permanently have to consciously choose what they want to learn. The conversation discussed the assumption that this might cause motivational problems. The first note shows openness for all the components and received follow-up. The second note shows a much less open character with only two indices of openness and received no follow-up. Figure 3 illustrates the analysis of openness in ATLAS.ti® using the codes for the eight indicators of openness, attached to text fragments in which openness was observed.

Full text of two KF notes with codes for socio-cognitive openness attached to selected text fragments in ATLAS ti®. Font style of text between brackets is changed for reasons of clarity. Italics indicate social openness, bold font indicates cognitive openness. “Ziehe” and “Illeris” refer to first authors in the course reading material. Texts were translated from Dutch

In the first KF note, the maximum of social and cognitive openness was found. In this note, student P96 responds to student P86, who states that teachers have to set rules to overcome motivational problems and invites those students in the community who are teachers themselves, to express their opinion on this. The note reveals cognitive openness in adding new information based on course material (i.e., the textbook written by IllerisFootnote 1) (elaboration), and shows how different insights from theory combined with an own opinion (expressing uncertainty) underpin the claim that students need structure, rules and clarification (multiple justification). The note ends with an invitation to bring in different viewpoints (thereby questioning own claims). Social openness is manifested by building on P86’s note (other transactivity) and by giving an opinion (expert authority) about someone else’s problem (joint ownership) in “even though I myself am not working as a teacher I agree that students need structure …”. The claim that learning to deal with frustration is part of the game expresses a moral view of the contributor (personal positioning). Figure 3 demonstrates that text fragments which reveal openness for the different indicators show overlap, in that three out of four indicators of cognitive openness in this example are clustered around a particular part of the text.

In contrast to the first KF note, the second note contains only two indicators of openness. With this note, student P100 responds to a note of student P71, who gave a representation of Ziehe’s thoughts on the problematic effects of the culture of optionality that students live in and the demands this imposes on teachers. P71 asked other community members who are teachers how they think about the suggested solution. The response of P100 shows other transactivity (“Hi P71, You have perfectly expressed this…”). The note also indicates elaboration by stating that Ziehe’s theory has implications for the role of teachers in dealing with students, although it remains unclear what the knowledge claim would consist of exactly. Despite the fact that uncertainty and enthusiasm about knowledge claims in the preceding KF note are expressed, these characteristics cannot be related to a specific knowledge claim, and therefore no manifestations of other indicators of openness in building knowledge were found in this KF note.

To examine the relationship between the components of the framework in the data, coding results were subjected to Principal Components Analysis for Categorical Data (CATPCA) in SPSS, version 24. Principle components analysis with Promax Kaiser rotation yielded two dimensions in the model with Eigen values exceeding 1, accounting for 36.2% of the total variance. Dimension 1 explained 20.9% of the variance (loadings ranging from .36–.75), while dimension 2 explained 15.2% of the variance (loadings ranging from .49–.70). The two extracted dimensions show strong similarities with the theoretical framework, with the four cognitive components (connecting knowledge, justifying knowledge claim(s), epistemic stance and inviting response) included in dimension 1, and three social components (ownership, positioning towards the claim and authority) included in dimension 2. One social dimension component (transactivity) was not included in the model. For this study, the authors maintain the theoretical importance of this component as an indicator of intersubjective stance. Therefore, as this study is the first empirical data analysis using the socio-cognitive framework, it was decided to maintain authority as part of the framework until more extended analysis has been carried out.

Table 2 shows the overall degree of socio-cognitive openness resulting from the analysis of the full sample. The degree of social openness in KF notes (M = 2.37; SD = .89), is higher than the degree of cognitive openness (M = 1.60; SD = .88), t(594 = 16,60, p < .001).

Further examination of the frequency distribution of the overall socio-cognitive openness scores showed that all the socio-cognitive scores from the minimum score of zero (2 notes) to the maximum score of eight (1 note) were present in the data. At the extremes, there were two KF notes showing no openness at all, and one showing openness for every component in the framework. The average number of openness indicators in the notes was 4 (152 notes).

Figure 4 shows the proportions of notes in which openness indicators were observed for each component. Frequently observed openness was found in elaboration (92.4%), other transactivity (91.8%) and expert authority (77.3%). More evenly divided scores were observed in joint ownership (51.5%) and relativist stance (44.1%). Openness was not frequently observed in questioning of the knowledge claim (16.8%), personal positioning (16.2%) and multiple justification (6.9%). The frequency of openness within the knowledge building discourse acts differs substantially for the underlying indicators (e.g., building knowledge 92.4% - 6.9%, expression of uncertainty 44.1% - 16.8%, community orientation 91.8% - 51.5% and expression of self 77.3% - 16.2%).

The relatedness of socio-cognitive openness to follow-up

To examine differences in social and cognitive openness, the average dimension scores (Msocial = 2.37; Mcognitive = 1.60) were used as a separation point to divide the data into either high or low level openness notes. Subsequently, the level of socio-cognitive openness was related to community type, trimester and teacher-student role. McNemar’s tests indicated that for the social and cognitive dimension, the level of openness was different depending on community type. Full community views had more high social as well as high cognitive openness dimension scores compared to sub communities (p < .01). Chi-square tests revealed a small difference in the cognitive dimension score related to trimester (χ2(2) = 6.75, p < .05).Trimester 2 had more high scores for cognitive openness than the other trimesters, although the effect size was small (ɸ = .13). For the social dimension, trimester was not significantly related to the level of openness. With regard to teacher-student role, descriptive analysis revealed that 65 of the analyzed KF notes (10.9%) were contributed by the course teachers. McNemar’s test showed that teachers’ contributions were more often characterized by a high level of social openness than students’ contributions (p < .01). For cognitive openness no difference in the level of openness was found. Teachers’ KF notes received less follow-up than expected compared to students’ notes (p < .01).

Out of 594 analyzed units, 282 (47,5%) had follow-up notes; 312 KF notes (52,5%) lacked follow-up. To examine whether socio-cognitive openness of KF notes for the dimensions of openness were related to follow-up, McNemar’s tests were conducted. For both the social and cognitive openness dimension, the results did not indicate a significant association between dimension scores of KF notes and having follow-up notes. For the components of the social and cognitive dimension of openness, McNemar’s tests revealed a mixed picture of the relationships with follow-up. With regard to the social dimension, two components (transactivity and authority) were found to be significantly associated to follow up (p < .01) in the sense that KF notes that are open with respect to these components were less likely to receive follow up, whereas the components ownership and positioning towards the knowledge claim were not significantly associated with having follow-up notes. On the other hand, regarding the cognitive dimension, three components were significantly related to follow-up, in that KF notes showing openness for the components connecting knowledge, justifying knowledge claims and inviting response had more follow-up than expected (p < .01). The cognitive component epistemic stance was not significantly related to follow-up.

The findings for the relatedness of the separate components of the framework to follow-up were supported by additional chi-square tests relating the four discourse acts to follow-up. For the social dimension, notes having openness for both components of community orientation had less follow-up than expected (χ2(2) = 13.91, p < .01), while expression of self showed no significant association with follow-up. On the other hand, for the cognitive dimension, notes lacking openness for building knowledge had less follow-up than expected (χ2(2) = 10.93, p < .01). Notes having openness for both components of expression of uncertainty had more follow up than expected (χ2(2) = 11.93, p < .01).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate how socio-cognitive openness manifests itself in the online discourse of two knowledge building communities of Master’s students and how openness relates to the continuation of their conversations. Findings indicate that: (a) those Knowledge Forum contributions studied show on average a moderate degree of openness, with a higher social than cognitive openness; (b) community type, trimester and teacher-student role within the Master’s program have little impact on the presence of openness; (c) cognitive openness has a positive impact on follow up, but social openness does not; and (d) the openness indicators that are most likely to receive follow-up are not identical to the indicators that are most often used. In sum, this study indicates that socio-cognitive openness matters: it impacts upon the chance of receiving follow-up and affects the continuation of online conversations, depending on the character of openness that is reflected in the online contributions. The results suggest that socio-cognitive openness is one of the determinants of the socio-cognitive dynamics of knowledge building discourse as a process of evaluation of ideas and generation of new insights, as described by Scardamalia (2002). In particular the cognitive dimension seems to be conducive to continuation of the discourse, whereas the social dimension does not contribute or even could bring continuation to a halt.

Moderate openness, with a more social than cognitive nature

This study found large differences in the presence of openness for the various components in the framework. Of the eight components of openness, three constituted a frequently observed pattern by indicating expert authority in building on another participant’s notes through adding knowledge claims. Openness was observed less frequently for the other five components. In general, the degree of social openness was higher than that of cognitive openness.

It was also observed that within the four knowledge building discourse acts there is a tendency to use one of the indicators more often than the other. Possibly, this indicates that community members deliberately show a moderate degree of openness with regard to the discourse acts. This might be due to previous educational settings that the students experienced, in which individual learning was advocated instead of the knowledge building pedagogy that was adopted in the Master’s program. As a consequence, contributing online on an individual basis might be an issue for the students. Posting contributions to knowledge building discourse may be viewed as publicly displaying knowledge. Not using certain types of openness (i.e. questioning their knowledge claims, taking a multi-perspective, showing a personal stance) might be students’ strategy to avoid being held accountable for the constructed knowledge, as was suggested by Lester and Paulus (2011). From this perspective, not being open functions as a rhetorical move to stay safe in the discourse and avoid the challenge of exploring knowledge outside the safe borders of the educational context. A tentative suggestion is that there is a hierarchy in openness indicators, from the more basic ones that were used frequently, to more subtle ones relating to discourse acts such as expression of uncertainty and the expression of self. These subtler expressions of openness might be of a more demanding nature and therefore possibly emerge only in a later stage in the program, when practices for knowledge building discourse have been re-negotiated and incorporated into the community culture. As Wise and Schwarz (2017) have stated, the development of a group into a community takes place simultaneously at the individual, small-group and collective level and takes time. The present explorative study did therefore possibly not capture the full development of the community culture. Similarly, community members’ development of self-awareness may not have fully developed yet. Individuals may lack the awareness or the repertoire to position themselves to engage in the process of intersubjective stance taking. They may feel reluctant “to stamp their personal authority onto their arguments” and instead “step back and disguise their involvement” (Hyland 2005, p. 176). Such factors might provide an explanation for the limited degree of taking stances in the community discourse.

Community type, trimester and student-teacher role have little impact on the presence of openness

From the small differences in the degree of social and cognitive openness related to community type and for the trimesters it is apparent that the manifestation of openness is a relatively stable fact in the context of the first year of the Master’s program. Socio-cognitive openness appears not to be related to trimester differences such as the course subject and assignments, the organization and facilitation of the courses and the course teachers’ communication style. Also, the fact that the degree of openness hardly changes during the trimesters, suggests that gaining experience as a knowledge building community during the first year of study does not impact on openness as a feature of a gradually developing community culture, as might be expected in the course of time (Barab 2003; Barab and Duffy 2000). There was however a slight difference between the degree of openness of messages between students and teachers: teachers’ contributions were on average slightly more socially open, whereas for cognitive openness no difference was found. A possible explanation is that social openness relates to the role of facilitator, whereby teachers act differently according to their role, as was indicated by Schrire (2006) and Zingaro and Oztok (2012). It is plausible that due to their role perception, teachers focused more on the concerns of others or the community than students on average do.

Cognitive openness impacts follow-up positively, social openness does not

Findings indicated that for several components and discourse acts, cognitive openness appears to be beneficial to follow-up and social openness has no bearing on follow-up. Contributions that elaborate on knowledge claims from others, make use of multiple justification and invite others to contribute alternative standpoints received more follow-up. Indeed, the results are congruent with studies of Gweon et al. (2013) and Weinberger and Fischer (2006) indicating that cognitive activities such as reasoning on knowledge claims expressed earlier in the conversation are key to sustaining knowledge building. In addition, the results support the claim of Chinn et al. (2011) that expressing different perspectives and communicating openness to different viewpoints foster the development of initial ideas and beliefs into better supported views. For social openness the results of the study are reversed in that the social openness components do not relate to follow up or are actually associated with less follow-up, as is the case for the components transactivity and authority. Similar results were obtained at the framework level of discourse acts. Here, the results seem to contradict previous research findings that absence of indications to own beliefs might hinder follow-up (Ioannou et al. 2014) or that openness as a result of language containing features of orientation towards the other would more easily lead to follow up (Jeong 2006). At present it is unclear how these results can be explained. Further study is needed to investigate whether or not social openness could be beneficial in community knowledge building.

Manifested openness does not correspond with openness that leads to follow-up

It is striking that of the three frequently used indicators of openness, only elaboration supported the continuation of the conversation by generating more follow-up. The other two often used indicators of openness (e.g. other transactivity and expert authority) were instead associated with less follow-up. These findings indicate that the repertoire of openness that was often used and remained stable over the three trimesters is not particularly efficient for continuation, and that a more favorable repertoire for sustaining the knowledge building discourse – containing indicators of the expression of uncertainty - was not optimally used. This study suggests that the expression of uncertainty in the making of knowledge claims is a key variable in the framework of socio-cognitive openness that may lead to discourse in which the social-cognitive dynamics more effectively support the process of community knowledge building. Findings regarding the expression of uncertainty are in line with existing literature emphasizing the value of expressing uncertainty with regard to knowledge claims (Chinn et al. 2011; Goodman et al. 2005; Howley et al. 2013). Expressing uncertainty contributes to the open space needed to explore ideas in the knowledge building process (Jordan et al. 2012). Further work might explore why uncertainty is not expressed more frequently in the discourse and how knowledge building discourse may benefit from this discourse act.

Implications for practice

Previous studies into knowledge building in communities have indicated that meta-discourse is not easily realized (Scardamalia and Bereiter 2006; van Aalst 2009). Educational practices that build their pedagogy around knowledge building communities may benefit from the socio-cognitive openness framework in that it offers community members an educational vocabulary to evaluate the discourse and thereby gives an impulse to the meta-discourse of a community. The knowledge building discourse acts in the framework (i.e., building knowledge, expression of uncertainty, community orientation and expression of self) provide teachers and students with an accessible and efficient language for reflection on their knowledge building communication and knowledge results and possibly also impacts the awareness of self of individuals and community as a whole. Reflection on the openness of teachers may help them to consolidate their critical role as facilitator by contributing with more cognitive openness compared to social openness, and in so doing, evoking more follow-up from students.

Limitations and directions for future research

The present study has used a novel analysis perspective to provide an impression of the role of socio-cognitive openness in sustaining online knowledge building discourse. Some methodological limitations should be mentioned here. Many CSCL studies, including the present one, use data from collaborative settings within fixed groups and as a consequence violate the assumption of the independence of observations (Janssen et al. 2011; Nussbaum 2008). This problem has been accounted for by using McNemar tests where possible. However, the results should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, we acknowledge that the binary coding scheme did not capture nuances of openness within each component. Further development of the coding scheme is warranted to yield a sharper picture of openness and its effects in collaboration processes. Nevertheless, the framework offers the CSCL research community an interesting perspective to further investigate the socio-cognitive dynamics of discourse needed to expand the dialogic space needed for students’ thinking and learning together (Wise and Schwarz 2017) and for instance enhance our understanding of phenomena such as rotating leadership in the discourse (Ma et al. 2016).

This study did not examine how the degree of openness relates to the realized levels of the knowledge in the discourse as a result of idea improvement, nor whether the expression of openness correlates with individual epistemic beliefs or perceptions of collaboration. These are directions for research which the authors of this study will address in a future study. As socio-cognitive openness is relevant in all kinds of situations in which knowledge is constructed collaboratively, it is also an interesting idea for future research to use the lens of socio-cognitive openness to investigate the dynamics of knowledge building in other types of conversations aiming at collaboration, such as synchronous or face-to-face knowledge building communication. In fact, online collaboration in educational contexts is frequently embedded in blended learning arrangements, as was the case in the present study. Using the socio-cognitive openness framework, the research into the online social-cognitive dynamics can be extended to include the more comprehensive communication of knowledge building discourse.

Notes

Illeris, K. (Ed.). (2009). Contemporary theories of learning. Learning theorists ... in their own words. New York: Routledge.

References

Baehr, J. (2015). The structure of open-mindedness. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 41, 191–214.

Barab, S. A. (2003). An introduction to the special issue : Designing for virtual communities in the Service of Learning. The Information Society, 19, 197–201.

Barab, S. A., & Duffy, T. M. (2000). From practice fields to communities of practice. In D. H. Jonassen & S. M. Land (Eds.), Theoretical Foundations of Learning Environments (pp. 25–55). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. (2014). Knowledge building and knowledge creation: One concept, two hills to climb. In S. C. Tan, H. J. So, J. Yeo (Eds.), Knowledge Creation in Education (pp. 35–52). Singapore: Springer.

Cacciamani, S., Cesareni, D., Martini, F., Ferrini, T., & Fujita, N. (2012). Influence of participation, facilitator styles, and metacognitive reflection on knowledge building in online university courses. Computers and Education, 58, 874–884.

Chinn, C. A., Buckland, L. A., & Samarapungavan, A. (2011). Expanding the dimensions of epistemic cognition: Arguments from philosophy and psychology. Educational Psychologist, 46(3), 141–167.

Clarà, M., & Mauri, T. (2010). Toward a dialectic relation between the results in CSCL: Three critical methodological aspects of content analysis schemes. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 5, 117–136.

Cress, U., & Kimmerle, J. (2008). A systemic and cognitive view on collaborative knowledge building with wikis. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 3, 105–122.

de Jong, F. P. C. M. (2015). Understanding the difference - responsive education: A search for ‘a difference which makes a difference’ for transition, learning and education. Wageningen: The Netherlands.

Dennen, V. P. (2005). From message posting to learning dialogues: Factors affecting learner participation in asynchronous discussion. Distance Education, 26, 127–148.

du Bois, J. W. (2007). The stance triangle. Stancetaking in Discourse: Subjectivity, Evaluation, Interaction, 164(3), 139–182.

Friese, S. (2014). Qualitative data analysis with ATLAS.Ti. London: Sage.

Fu, E. L. F., van Aalst, J., & Chan, C. K. K. (2016). Toward a classification of discourse patterns in asynchronous online discussions. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 11, 441–478.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2010). The first decade of the community of inquiry framework: A retrospective. The Internet and Higher Education, 13, 5–9.

Goodman, B. A., Linton, F. N., Gaimari, R. D., Hitzeman, J. M., Ross, H. J., & Zarrella, G. (2005). Using dialogue features to predict trouble during collaborative learning. User Modelling and User-Adapted Interaction, 15, 85–134.

Gweon, G., Jain, M., McDonough, J., Raj, B., & Rosé, C. P. (2013). Measuring prevalence of other-oriented transactive contributions using an automated measure of speech style accommodation. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 8, 245–265.

Hong, H.-Y., & Sullivan, F. R. (2009). Towards an idea-centered, principle-based design approach to support learning as knowledge creation. Educational Technology Research and Development, 57(5), 613–627.

Howley, I., Mayfield, E., & Rosé, C. P. (2011). Missing something? Authority in collaborative learning. In Proceedings of the 9 th international computer supported collaborative learning conference (pp. 336–373).

Howley, I., Mayfield, E., Rosé, C. P., & Strijbos, J. (2013). A multivocal process analysis of social positioning in study groups. In: Suthers, D.D., Lund, K., Penstein Rosé, C.P., Teplovs, T. & Law, N. (Eds.), Productive Multivocality in the Analysis of Group Interactions, computer-supported collaborative learning series 16, New York, NY, Springer.

Hyland, K. (2005). Stance and engagement: A model of interaction in academic discourse. Discourse Studies, 7(2), 173–192.

Ioannou, A., Demetriou, S., & Mama, M. (2014). Exploring factors influencing collaborative knowledge construction in online discussions : Student facilitation and quality of initial postings. The American Journal of Distance Education, 28, 183–195.

Janssen, J., Erkens, G., Kirschner, P. A., & Kanselaar, G. (2011). Multilevel analysis in CSCL research. In Analyzing interactions in CSCL (pp. 187–205). Boston, MA: Springer.

Jeong, A. C. (2006). The effects of conversational language on group interaction and group performance in computer-supported collaborative argumentation. Instructional Science, 34, 367–397.

Jordan, M. E., Schallert, D. L., Park, Y., Lee, S., Chiang, Y. V., Cheng, A.-C. J., Song, K., Chu, H. N. R., Kim, T., & Lee, H. (2012). Expressing uncertainty in computer-mediated discourse: Language as a marker of intellectual work. Discourse Processes, 49, 660–692.

Kärkkäinen, E. (2006). Stance taking in conversation: From subjectivity to intersubjectivity. Text & Talk, 26, 699–731.

Ke, F., Chávez, A. F., Causarano, P.-N. L., & Causarano, A. (2011). Identity presence and knowledge building: Joint emergence in online learning environments? International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 6, 349–370.

Koschmann, T. (1999). Toward a dialogic theory of learning: Bakhtin's contribution to understanding learning in settings of collaboration. In Proceedings of the 1999 conference on computer support for collaborative learning (p. 38) International Society of the Learning Sciences.

Lester, J. N., & Paulus, T. M. (2011). Accountability and public displays of knowing in an undergraduate computer-mediated communication context. Discourse Studies, 13, 671–686.

Ligorio, M. B., Loperfido, F. F., & Sansone, N. (2013). Dialogical positions as a method of understanding identity trajectories in a collaborative blended university course. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 8, 351–367.

Loperfido, F. F., Sansone, N., Ligorio, M. B., & Fujita, N. (2014). Understanding I/we positions in a blended university course: Polyphony and chronotopes as dialogical features. Open and Interdisciplinary Journal of Technology, Culture and Education, 9(2), 51–66.

Love, A. G. (2012). The growth and current state of learning communities in higher education. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2012(132), 5–18.

Ludvigsen, S. R., & Mørch, A. I. (2010). Computer-supported collaborative learning: Basic concepts, multiple perspectives, and emerging trends. International Encyclopedia of Education, 290–296.

Ma, L., Matsuzawa, Y., & Scardamalia, M. (2016). Rotating leadership and collective responsibility in a grade 4 knowledge building classroom. International Journal of Organisational Design and Engineering, 4, 54–84.

Martin, J. R., & White, P. R. (2003). The language of evaluation. Appraisal in English. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mitchell, R., & Nicholas, S. (2006). Knowledge creation in groups : The value of cognitive diversity, Transactive memory and open-mindedness norms. Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 4, 67–74.

Ness, I. J., & Riese, H. (2015). Openness, curiosity and respect : Underlying conditions for developing innovative knowledge and ideas between disciplines. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 6, 29–39.

Nussbaum, E. M. (2008). Collaborative discourse, argumentation, and learning: Preface and literature review. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 33, 345–359.

Paavola, S., & Hakkarainen, K. (2005). The knowledge creation metaphor – An emergent epistemological approach to learning. Science & Education, 14, 535–557.

Paavola, S., Lipponen, L., & Hakkarainen, K. (2004). Models of innovative knowledge communities and three metaphors of learning. Review of Educational Research, 74, 557–576.

Rourke, L., Anderson, T., Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing social presence in asynchronous text-based computer conferencing. Journal of Distance Education, 1–18.

Scardamalia, M. (2002). Collective cognitive responsibility for the advancement of knowledge. Liberal Education in a Knowledge Society, 97, 67–98.

Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (2006). Knowledge building: Theory, pedagogy, and technology. In K. Sawyer (Ed.), Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 97–118). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (2010). A brief history of knowledge building. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 36, 1–16.

Schrire, S. (2006). Knowledge building in asynchronous discussion groups: Going beyond quantitative analysis. Computers and Education, 46(1), 49–70.

Skidmore, D., & Murakami, K. (2012). Claiming our own space: Polyphony in teacher–student dialogue. Linguistics and Education, 23, 200–210.

Song, Y. (2017). The moral virtue of open-mindedness. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 5091(June), 1–20.

Stahl, G. (2012). Traversing planes of learning. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 7, 467–473.

Strijbos, J. W., Martens, R. L., Prins, F. J., & Jochems, W. M. G. (2006). Content analysis: What are they talking about? Computers and Education, 46(1), 29–48.

Suthers, D. D., Lund, K., Rosé, C. P., & Teplovs, C. (2013). Achieving productive multivocality in the analysis of group interactions. In D. D. Suthers, K. Lund, C. P. Rosé, C. Teplovs, & N. Law (Eds.), Productive multivocality in the analysis of group interactions (pp. 577-612). Boston, MA: S pringer.

van Aalst, J. (2009). Distinguishing knowledge-sharing, knowledge-construction, and knowledge-creation discourses. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 4, 259–287.

van Heijst, H., de Jong, F., & Kirschner, P. (2019). Developing a descriptive framework for understanding the socio-cognitive dynamics of knowledge building discourse. Unpublished manuscript.

Wegerif, R., McLaren, B. M., Chamrada, M., Scheuer, O., Mansour, N., Mikšátko, J., & Williams, M. (2010). Exploring creative thinking in graphically mediated synchronous dialogues. Computers & Education, 54, 613–621.

Weinberger, A., & Fischer, F. (2006). A framework to analyze argumentative knowledge construction in computer-supported collaborative learning. Computers & Education, 46, 71–95.

Wise, A. F., & Schwarz, B. B. (2017). Visions of CSCL: Eight provocations for the future of the field. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 12, 423–467.

Wise, A. F., Marbouti, F., Hsiao, Y. T., & Hausknecht, S. (2012). A survey of factors contributing to learners' “listening” behaviors in asynchronous online discussions. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 47, 461–480.

Zhang, J., Scardamalia, M., Reeve, R., & Messina, R. (2009). Designs for collective cognitive responsiblity in knowledge building communities. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 18, 7–44.

Zingaro, D., & Oztok, M. (2012). Interaction in an asynchronous online course. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 16(4), 71–82.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a PhD-grant for teacher-researchers by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

van Heijst, H., de Jong, F.P.C.M., van Aalst, J. et al. Socio-cognitive openness in online knowledge building discourse: does openness keep conversations going?. Intern. J. Comput.-Support. Collab. Learn 14, 165–184 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-019-09303-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-019-09303-4