Abstract

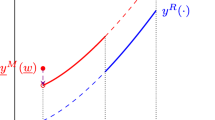

Preferences over social ranks have emerged as potential drivers of weaker than expected support for redistributive interventions among those closest to the bottom of the income distribution. We compare preferences for alterations of the income distribution affecting the decision maker’s social rank, but not their income, and compare them with similar alterations leaving both rank and income unchanged. Our study fails to find evidence of last-place aversion in a replication of Kuziemko et al. (Q J Econ 129(1):105–149, 2014). However, using a modified design that holds ranks fixed across rounds we find support for both a discontinuously greater disutility from occupying the last as opposed to higher ranks, thus affecting only those closest to the bottom of the distribution, and for a general dislike of rank reversals affecting most ranks. We discuss implications for policy design in both public finance and management science.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Even should one’s relative position not enter the utility function directly, outcomes that people care about, such as job or marriage quality or access to food, depend on their rank in the distribution (e.g. of income, education, attractiveness). It hence makes evolutionary sense that people would care about rank.

Support can be found in evolutionary arguments: the weakest animal in a herd is usually the last to eat and the first to perish.

KBRN also run an experiment linking individuals’ rank to their propensity to purchasing risky lotteries. While the lottery games offer important insights into rank preferences, the scope of this paper is limited to the modified dictator game described in what follows.

The two Dollars did not originate from the allocator’s endowment.

We will often use the shorthand “to allocate downwards” in referring to the choice of allocating to the lower ranked person in one’s choice set. For ranks two to five this choice translates into allocating to the subject ranked immediately below oneself (see Sect. 2).

KBRN do not take a stance on whether last place aversion works differently if the last rank is shared by multiple individuals (they formally define last place aversion only for the case in which individuals have distinct incomes). We extend their theoretical model to account for situations in which the last place is shared (see Online Appendix D). Whether shared or not, ending up in the last place will qualitatively yield the same result of being “last”, and will still be (discontinuously) worse than occupying any higher rank. From an evolutionary perspective, for instance, the chance of being hunted down by a pride of predators is 100% for the weakest and slowest animal. If two animals are equally weak it depends on how large the pride is. Each weak animal is however still caught with a probability of at least 50% (still discontinuously higher than the chance of any other member of the herd being caught).

We cannot exclude that other mechanisms might be at play between our RR and NoRR conditions. Our design is to the best of our knowledge the closest possible to that of KBRN to, simultaneously, enable a meaningful one-step deviation comparison and allow the removal of rank reversals as confounders of last place aversion. As pointed out by a referee, a concern in this respect is that different amounts are being transferred between individuals. As discussed in Online Appendix D, however, inequity aversion (Fehr and Schmidt 1999) cannot explain behavioural differences across RR and NoRR conditions. Further, Xie et al. (2017) show that aversion to rank reversals is stronger than aversion to inequality as subjects in their experiment tend to prefer rank preservation to equalisation of incomes.

Konrad and Morath (2010) show that “perceived social mobility” (i.e. mobility in the experimental income distribution from one round to the next, without any implications for current round incomes) has an effect on people’s redistributive choices, even if these choices only concern a given round and have no implications for the rest of the session.

We acknowledge that examples countering such arguments exist. These are however, arguably, rather exceptional cases.

As rightly suggested by a referee, fixing ranks may offer the further advantage of allowing the subjects to better understand the structure of the game, ultimately allowing them to make choices that are more (repeatedly) consistent with its intrinsic (material and non-material) incentive structure.

We adjusted the distribution used by KBRN to meet our subject payment requirements.

Confusion could arise according to how to number and evaluate ranks. We decouple rank numbering from rank prestige, adhering to the dominant representation of rankings in our culture. We define the rank of a person with income \(y_i\) as “one plus the number of individuals with incomes higher than \(y_i\)”. Rank 1 is therefore the highest and rank 6 the lowest. A positive relationship between rank and propensity to allocate downwards would therefore have high prestige (low-numbered) ranks display the highest propensity while low prestige (high-numbered) ranks the lowest. An alternative perspective would assign high numbers to high prestige ranks and low numbers to low prestige ranks. We however feel such approach would be less intuitive and less immediately applicable to our everyday experience.

As the distribution here adopted proceeds in increments of two Euros between contiguous subjects, we accordingly adjusted the amount subjects could allocate.

Other behavioural theories all predict subjects to always allocate downwards (Online Appendix D).

Notice however that the potential negative impact of boredom may be balanced by the subjects’ desire to choose (mindlessly) consistently across repeated identical tasks.

Summarising, Part 2 consisted of 15 more repetitions of the game played in Part 1 but including an additional choice conditional on the endowment of the next-in-rank being randomly unchanged, increased or decreased by 1 unit. Part 3 consisted of the elicitation of the subjects’ basic Social Value Orientation (Murphy et al. 2011).

The data was collected in two waves. We collected data for all conditions in the summer/autumn of 2018, and again in the autumn of 2019 for the fixed conditions. We use the target effect size observed in KBRN to compute the power of our study: i.e. a proportion below 0.6 (which we conservatively round up to 0.6) of subjects ranked fifth and a proportion above 0.8 (which we conservatively round down to 0.8) of subjects ranked second allocating money downwards. In each condition, we have a number of independent observations equal to the number of subjects participating in that condition. As the subjects participate in a series of independent repetitions of the game (no feedback is provided across repetitions with stranger matching) the number of observations in each rank is given by the number of subjects choosing in each rank multiplied by the number of repetitions. Our power in a two-sample proportions test exceeds \(power=0.9\) at \(\alpha =0.05\) in all conditions.

See Online Appendix D for a detailed discussion.

The output of the probit regressions are reported in Online Appendix A.

Here, and throughout the rest of the paper, analogous Fisher’s Exact tests lead to the same conclusions as the reported PR tests.

P values in Fig. 2.

p values reported in Fig. 2.

Regression coefficients reported in Online Appendix B.2.

Notice that the same is not true for higher ranks.

Recall that in NoRR and NoRRfixed downwards allocations do not cause the subjects to lose their rank, but allow the subject ranked immediately below to “catch up”.

A curious counterexample was pointed out to us. The rather unflattering title of “lanterne rouge” (“tail lamp”, in English) is assigned to the last classified competitor in the cycling competition “Tour de France”. The “lanterne rouge” is devoted a substantial amount of media and sponsor attention, resulting in at least one known case of competition to classify last in the race. While countering our reasoning, the peculiar circumstances surrounding and the media attention devoted to the “lanterne rouge” make it a case hardly generalisable to other contexts.

One may argue that only the first place is associated with the greatest utility. We do not dispute that. However, we point out that despite the fact that utility may decrease sharply with the second and even further with the third rank, any sports passionate would agree that neither the second nor the third placed athlete would be glad to share their place with the next classified contestant (if not symbolically by allowing them to step on their podium stall, or for other types of prestige or notoriety gains).

While no competition takes place in our framework, we believe that our results would be amplified by the presence of active competition for the ranks among the subjects.

References

Alesina, A., Miano, A., & Stantcheva, S. (2018). Immigration and redistribution. Working paper 24733, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2004). Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics, 88(7), 1359–1386.

Bolton, G. E., & Ockenfels, A. (2000). ERC: A theory of equity, reciprocity, and competition. The American Economic Review, 90(1), 166–193.

Camerer, C. F., Dreber, A., Forsell, E., Ho, T.-H., Huber, J., Johannesson, M., et al. (2016). Evaluating replicability of laboratory experiments in economics. Science, 351(6280), 1433–1436.

Card, D., Mas, A., Moretti, E., & Saez, E. (2012). Inequality at work: The effect of peer salaries on job satisfaction. The American Economic Review, 102(6), 2981–3003.

Charness, G., & Rabin, M. (2002). Understanding social preferences with simple tests. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(3), 817–869.

Duesenberry, J. S. (1949). Income, saving, and the theory of consumer behavior. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Falk, A., & Fischbacher, U. (2006). A theory of reciprocity. Games and Economic Behavior, 54(2), 293–315.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(3), 817–868.

Ferrer-i Carbonell, A. (2005). Income and well-being: An empirical analysis of the comparison income effect. Journal of Public Economics, 89(5), 997–1019.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10(2), 171–178.

Fong, C. (2001). Social preferences, self-interest, and the demand for redistribution. Journal of Public Economics, 82(2), 225–246.

Gilens, M. (2009). Why Americans hate welfare: Race, media, and the politics of antipoverty policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gill, D., Kissová, Z., Lee, J., & Prowse, V. (2018). First-place loving and last-place loathing: How rank in the distribution of performance affects effort provision. Management Science, 65(2), 459–954.

Greiner, B. (2015). Subject pool recruitment procedures: Organizing experiments with ORSEE. Journal of the Economic Science Association, 1(1), 114–125.

Konrad, K. A., & Morath, F. (2010). Social mobility and redistributive taxation. In WZB markets and politics working paper no. SP II (p. 15).

Kuziemko, I., Buell, R. W., Reich, T., & Norton, M. I. (2014). “Last-place aversion”: Evidence and redistributive implications. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(1), 105–149.

Luttmer, E. F. P. (2005). Neighbours as negatives: Relative earnings and well-being. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(3), 963–1002.

Martinangeli, A., & Windsteiger, L. (2019). Immigration vs. poverty: Causal impact on demand for redistribution in a survey experiment. In Working paper of the Max Planck Institute for Tax Law and public finance no. 2019–13.

Murphy, R. O., Ackermann, K. A., & Handgraaf, M. (2011). Measuring social value orientation. SSRN scholarly paper ID 1804189, Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY.

Rabin, M. (1993). Incorporating fairness into game theory and economics. The American economic review, 83(5), 1281–1302.

Smith, J. M. (1982). Evolution now: A century after Darwin. New York: Freeman.

Xie, W., Ho, B., Meier, S., & Zhou, X. (2017). Rank reversal aversion inhibits redistribution across societies. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(8), 0142.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to the editor Roberto Weber and two anonymous referees for invaluable guidance in the revision process, and to Duk Gyoo Kim, Werner Güth, Martin Kocher, Kai A. Konrad, Anna Ressi, Stefanie Stantcheva and to the participants in various seminars and workshops at the Max Planck Institute for Tax Law and Public Finance, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Otto von Guericke Universität, ZEW Mannheim, LUISS Guido Carli, Loughbourough University, Ifo Institute and TUM Munich for precious comments and suggestions. This work also received invaluable feedback from the participants of the SEET, IMEBESS, ASFEE, IIPF, IAREP/SABE, EU-ESA and SIEP conferences.Our debt of gratitude extends to Birgit Menzemer and the staff at the ECONLAB of the Max Planck Institute for Tax Law and Public Finance for efficiently organising and running the sessions.

Funding

Financial support was provided by the Max Planck Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors decalre that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martinangeli, A.F.M., Windsteiger, L. Last word not yet spoken: a reinvestigation of last place aversion with aversion to rank reversals. Exp Econ 24, 800–820 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-020-09682-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-020-09682-8

Keywords

- Income distribution

- Last place aversion

- Positional concerns

- Preferences for redistribution

- Rank reversal aversion