Abstract

In a technology-driven, digital world, many of the largest and most successful businesses now operate as ‘platforms’. Such firms leverage networked technologies to facilitate economic exchange, transfer information, connect people, and make predictions. Platform companies are already disrupting multiple industries, including retail, hotels, taxis, and others, and are aggressively moving into new sectors, such as financial services. This paper examines the distinctive features of this new business model and its implications for regulation, notably corporate governance. In particular, the paper suggests that a tension exists between the incentives created by modern corporate governance and the business needs of today’s platforms. The current regulatory framework promotes an unhealthy ‘corporate’ attitude that is failing platforms, and a new direction (what we term ‘platform governance’) is urgently required. In identifying this new regulatory direction, the paper considers how firms might develop as successful platforms. Although there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution, the paper describes three interconnected strategies: (1) leveraging current and near-future digital technologies to create more ‘community-driven’ forms of organization; (2) building an ‘open and accessible platform culture’; and (3) facilitating the creation, curation, and consumption of meaningful ‘content’. The paper concludes that jurisdictions that are the most successful in designing a new ‘platform governance’ based on the promotion of these strategies will be the primary beneficiaries of the digital transformation.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In a technology-driven, ‘digital world’, many of the largest and most successful businesses now operate and organize as open and inclusive ‘platforms’.Footnote 1 Most platforms leverage networked technologies to facilitate economic exchange, transfer information and connect people.Footnote 2 Think Amazon, Apple, Facebook, or Alphabet (Google).Footnote 3 These companies all facilitate interactions between creators and extractors of value and, in doing so, generate wealth for the platform owner-controller.Footnote 4 Thus, a platform derives value from its role as intermediary.Footnote 5

But platform companies do more than merely utilize new technologies to facilitate economic or social interactions between interested third parties. These companies also organize their internal operations in a flatter and more inclusive way to enable collaboration among multiple stakeholders.Footnote 6 By doing so, they maximize opportunities to deliver constant innovation in platform services and functionality.

It is this combination of features (which we term, respectively, ‘transaction facilitators’ and ‘organizing-for-innovation’) that distinguishes platform companies from more traditional business organizations. To develop a more historical account of the distinctive features of this ‘platform-style’ business, we contrast these organizations with the centralized, hierarchical organizational forms that dominated in an earlier phase of industrial capitalism.Footnote 7 Some suggest that we are living in a ‘platform age’ and that all firms—not just technology firms—should consider operating and organizing as a platform.Footnote 8 If they do not, they will be disrupted by existing platforms that will continue their aggressive expansion into new sectors and markets.Footnote 9

In this paper, we develop a conceptual framework for analyzing the governance of platform companies. Traditionally, corporate governance has emphasized the ‘primacy’ of shareholders—i.e., the economic, legal and moral owners of a company. Over time, policymakers have imposed measures on firms designed to compel the other actors within a company—mainly directors, executives, and managers—to act in the best interests of the shareholder-owners. Corporate governance measures were intended to protect the interests and control of those at the ‘top’ of the hierarchy (i.e., shareholders), and other considerations were of secondary importance. Moreover, the discourse and practice of corporate governance was an adaptation to—and a product of—a world of centralized, hierarchical organizations, primarily large corporations. This governance approach worked best when large corporations were the primary engines of economic growth, but it makes much less sense in an age of flatter, innovation-driven platforms.

Problems arise because the shareholder primacy model has not always operated as intended, and there have been several well-documented ‘side-effects’. These include a myopic focus on shareholder value and overly bureaucratized organizations. All too often, the unintended effect of corporate governance has been to entrench inefficient hierarchies and create a short-term and overly cautious corporate culture. What is the risk of such an approach? In the medium to long term, firms struggle to innovate and become corporate ‘dinosaurs’—i.e., lumbering giants facing extinction.

We review the traditional approach to corporate governance, the unintended problems that it has created, and recent policies aimed at promoting a longer-term and more socially and environmentally responsible view of corporate governance. Clearly, there is a tension between the regulatory incentives created by corporate governance and the business needs of most platform companies today. The question is whether the current regulatory framework promotes a healthy ‘corporate’ attitude for platform companies. Our analysis sheds light on how the current regulatory framework promotes a negative ‘corporate’ attitude that is failing platforms, and it suggests that a new direction—what we term ‘platform governance’—is urgently required.

How, then, do we develop a response to this regulatory challenge? One approach is to consider how firms might organize as successful platforms and then seek to align regulatory measures with such strategies and the interests of platforms. Although there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution, the paper outlines three interconnected strategies relevant to any firm looking to operate as a platform: (1) leveraging current and near-future digital technologies to create more ‘community-driven’ forms of business organization; (2) building an ‘open and accessible platform culture’; and (3) facilitating the creation, curation, and consumption of meaningful ‘content’. We describe these strategies and argue that they can benefit all businesses (both ‘old’ and ‘new’) that want to adapt to the unique challenges of a tech-driven, global economy.

This analysis also considers governance strategies that can help firms to promote a high degree of cooperation, loyalty and mutual trust. First, we show that a shift to new forms of communication may be especially significant in building a healthy bond among stakeholders. Moreover, it can help maintain a corporate culture of openness and honesty. Evidence suggests that the unmediated forms of corporate communications used to engage with stakeholders, especially via an annual letter, have become increasingly more important than official annual reports and conventional modes of financial communication. Second, the recent rise in the diversity of individuals appointed to corporate boards confirms the importance of their role in identifying issues and opportunities pertaining to disruptive innovation.

This paper concludes that, to identify new regulatory measures that help firms remain competitive in a global and digital age, policymakers must consider how best to incentivize firms to embrace these strategies. Moreover, the rise of platforms is disrupting both existing hierarchical business models and traditional understandings of corporate governance. In this context, existing regulatory models face an uncertain future. Those jurisdictions that are most successful in navigating this predicament and developing a new direction for corporate governance stand to be the primary beneficiaries of the digital transformation.

The structure of the paper is as follows. Section 2 reviews the distinction between the ‘platform-style’ business model and the ‘hierarchical firm’. Section 3 examines the underlying limitations of the traditional corporate governance model and considers why recent developments in corporate governance reform are unlikely to address the strategic governance needs of platform firms. Section 4 focuses on the three strategies for developing a successful platform organization and corporate culture. Section 5 concludes.

2 A ‘Platform Age’

In this section, we introduce the distinctive features of a ‘platform-style’ business model and contrast it with the hierarchical ‘firms’ that dominated in an earlier phase of industrial capitalism.

2.1 Platforms as Transaction Facilitators

There was a time when entrepreneurs could scale a new company by following a relatively simple formula: identify an existing business model for a product or service, ‘tweak’ it slightly, and focus all out on execution (e.g., standardizing production or service-delivery). Once the business was established, the pattern was similar; an ‘older’ firm could focus on making incremental improvements to its existing product or service line and on gradually expanding market share.Footnote 10

To achieve these objectives, firms were organized as closed, centralized, and hierarchical structures characterized by (1) a highly centralized source of authority; (2) a clear boundary between the firm and the ‘outside world’; (3) a settled and formal hierarchy with functionally differentiated ‘departments’ and ‘roles;’ and (4) standardized operating systems and procedures dictated by the centralized authority. Such a highly bureaucratized model of organizational design made sense when a firm’s primary objective was to minimize transaction costs and information asymmetries and deliver a (relatively) static product or service to a (relatively) stable national market.

However, the world is different now. All businesses now operate in hyper-competitive global markets against a background of the digital transformation (i.e., exponential technological growth and fast-moving consumer demands).Footnote 11 This new operating environment creates a constant pressure to innovate. Simple ‘tweaks’ to existing business models, products or services are no longer enough.Footnote 12

All firms today have to engage with the Internet, the Cloud, mobile technologies, and more; and the next wave of tech—currently, robotics, blockchain, and artificial intelligence—is already having an impact on extant business models. In an age of ever shorter innovation cycles, the subsequent significant technological development is always imminent. Anticipating, planning for, and integrating the next ‘big thing’, whatever it may be, is crucial to maximizing a firm’s chance of long-term success—or even its very survival.

So, how can firms organize now for success tomorrow? What should companies do now to innovate and remain successful in the future? What kind of structures, practices, and processes will best equip a firm to continually reinvent itself, its products and its services? And how can firms leverage new digital technologies to maximize their performance and capacity for innovation?

One important adaptation to the new economic and technological environment has been the emergence of ‘platforms’. The term ‘platform’ tends to be associated with different types of tech-companies—i.e., companies that operate a ‘social’ platform (Facebook, Instagram), an ‘exchange’ platform (Amazon, Airbnb, Uber), a ‘content’ platform (YouTube, Medium, Netflix), a ‘software’ platform (Apple iOS, Google Android), or even a ‘blockchain’ platform (Ethereum, EOS).

This is not surprising. After all, the emergence of these new platforms and services has been one of the significant economic and business developments of the last two decades. In fact, the world’s most successful companies now operate as platforms (see Fig. 1). It is noteworthy that the world of platforms is dominated by companies from the United States and China.

Source: Adapted from http://VisualCapitalist.com

The world’s largest tech companies.

In each of the above examples, the ‘platform’ creates value by facilitating exchanges between different but interdependent groups (see Table 1). These platforms leverage networked technologies to promote economic exchange, transfer information or connect people. These companies facilitate interactions between creators and extractors of value and then generate profit.

The popularity of the platform business model has grown in recent years with the development of a series of inter-connected technologies—the Internet, code-based algorithms, and PCs and smartphones. These technologies have advanced the platform business model by allowing the fast, large-scale exchange of products and information utilizing decentralized networks. This creates a global ecosystem that encourages registered users and content consumers to add more value to the platform by repeatedly creating more content, which will, in turn, attract additional content creators and consumers (i.e., platforms benefit enormously from ‘network effects’).

The use of platform thinking extends beyond the technology sector. Many traditional retailers are shifting their distribution channels for selling products from ‘stores’ to online platforms and services, as in the case of Ikea’s acquisition of TaskRabbit. Traditional industrial firms are also seeing themselves less as producers of goods and more as platform-based services. General Electric, for example, the archetypal industrial giant, has tried to transform itself from a hardware manufacturer to a data science company that utilizes platforms, software, and big data analytics. More recently, platforms have been moving into the financial services sector, requiring existing financial firms to consider operating their own platforms.

2.2 Platforms and Organizing-for-Innovation

However, we should recognize that there is more to ‘platform companies’ than simply using new technologies to facilitate transactions, exchange information, or connect people. There is another valuable lesson to be learned from the emergence and success of this type of company.

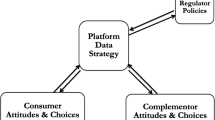

What these companies also have in common is that they organize their ‘internal’ operations to facilitate collaboration among multiple stakeholders and, thus, deliver constant innovation in the functionality of the platform and related products and services. These various stakeholders include managers, employees, and investors, as well as (crucially) consumers, developers, content creators, other companies (both large and small), non-profits, educational institutions, and governments (see Fig. 2). As such, smart platforms break from the traditional centralized, hierarchical and closed firm structure described above.

What makes platform-style organization distinctive is that it uses stakeholders’ input and feedback to improve users’ experience and engagement with the ‘platform’ and its products, services, and other solutions. This is another important lesson to be taken from the success of Amazon, Facebook, Netflix, etc. All of these companies are disrupting and ‘decentralizing’ existing business models by eliminating and replacing traditional intermediaries. These companies facilitate more direct ‘peer-to-peer’ transactions between service providers/creators/producers on the one hand and the consumers on the other.Footnote 13

The emergence of platforms has coincided with a profound decrease in information costs, and this transforms the traditional balance between the benefits of internal (firm-based) and external markets. In this sense, information technology contributes to an erosion of the boundary between the firm and the market.

In the best and most successful firms, governance is no longer about hierarchy, control or a clear border between the firm and the world. Instead, the focus is on creating a flat, open and inclusive organizational environment that leverages the talents of all stakeholders in that company’s network. As such, platforms are built around the idea of delivering constant innovation via an open and inclusive process of collaboration and co-creation. By organizing for innovation in this way, such platforms break from the clearly defined, fixed hierarchies, static roles, and authorized procedures of traditional business organizations.

Therefore, platform companies need to think about connecting with a community of users, an aspect of business that has become much more significant due to the enormous growth of social media. In this way, collaborative consumption—the shared use of a good or service by a group—is transforming conventional understandings of ownership and consumption. Both large established companies and startups have recognized the commercial opportunities of community-based business models and the importance of engaging with this aspect of connectivity.

Platforms have changed the way that we think and feel about new technology and innovation. We have become much more accustomed to life-changing technologies—think Internet, e-mail, smartphones—and, as a result, we all expect more. Within one generation, we have come to expect new technologies that offer even more connectivity, choice, and convenience. Our imaginations often run ahead of what current technologies can deliver. In a platform economy, all of us now have a highly developed sense of what technology might do and are more easily disappointed and frustrated when a new technology fails to meet these new expectations.

Businesses will either operate ‘as’ a platform or be ‘integrated’ within a platform. The future of the digital age will be platform-driven ecosystems in which multiple players participate. The most influential companies will be the ones that position themselves as platform owners (which typically control the platform).

As shown above, platforms are an adaptation to the realities of fast-emerging technologies and hyper-competitive global markets. For this reason, all businesses—not just tech-businesses—are now looking to reinvent themselves as platforms. By operating as platforms, many companies hope to build their capacity for disruptive innovation and ensure that they remain relevant. Established and ‘traditional’ companies must also undergo this transformation. The rule is straightforward: ‘You either become a platform, or you will be killed by one’.

Given the proliferation of platforms, we seem to be living through a shift from a world of firms to a new world of platforms. In the same way that the ‘firm’ came to replace ‘contracts’ for many business activities in the context of the industrial revolution, ‘platforms’ are now replacing ‘old-world firms’ in the context of the digital transformation.

Meeting this challenge is much easier said than done. As companies grow, they come to rely on hierarchical organizational structures. Such structures make sense as a strategy for managing the complexities of scale. The problem is that a hierarchical organization can result in the bureaucratization of firm culture. This type of organization and culture might have worked well in an era of mass production, but they are ill suited to today’s dynamic business realities. A tension can easily emerge between the structure and culture of a firm and what is required to succeed in an innovation-driven economy dominated by global platforms. The effect of this tension is that ‘established’ firms are unable to react effectively or quickly enough to the challenges of fast-paced changes in markets, consumers, and technologies. Such companies struggle to operate in an economy in which speed and innovation are everything.

3 Corporate Governance

This section argues that to assist businesses in organizing effectively as platforms, regulators and other policymakers need to revisit their approach to business regulation, particularly corporate governance. It also suggests that there is currently a disconnect between the regulatory pressures created by corporate governance (i.e., maintaining centralized authorities, hierarchy, and control) and the needs of firms seeking to establish themselves as successful platforms (i.e., connecting and facilitating collaborations among multiple stakeholders). To address this disconnect, we present a model of platform governance that includes the roles of social media, flatter and open organizations, and directors as ‘feedback providers’.

3.1 Corporate Governance as Shareholder Primacy

Traditionally, corporate governance refers to an organization’s structures and procedures that aim to ensure that (1) authority, responsibility and control flows ‘downwards’ from the investors (the economic, legal and moral ‘owners’ of the company) through a board of directors to management and, finally, to the employees; and (2) accountability flows ‘upwards’. The primary goal of corporate governance is to protect the interests of the investor/owner/shareholders (see Fig. 3).

It is evident from this definition that corporate governance is built on the idea of a closed, centralized authority, and of a clearly-defined hierarchy with distinct roles and functions. Moreover, corporate governance rules have been designed to protect the interests of those at the pinnacle of that hierarchy—namely, the investor-shareholders. As such, the discourse and practice of corporate governance was an adaptation to, and product of, a world of centralized, hierarchical organizations—large corporations in particular. This regulatory approach made sense when large corporations were the primary engines of economic growth.

In practice, this ‘shareholder primacy model’ requires firms to adopt measures designed to ensure that all of the other actors within the firm act ‘as if’ they were investor-shareholders. By aligning the incentives of the various actors in this way, firm performance—as measured by the share price—is improved, benefiting not only ‘all’ of the stakeholders in a firm, but also members of the public, who benefit from the goods and services that a successful firm provides.

This kind of framework has provided the context for modern debates around corporate governance—i.e., identifying regulations that compel or, at least, ‘nudge’ the ‘agents’ within the firm to act ‘as if’ they were owner-principals. In this respect, corporate governance has been heavily implicated in the rise of shareholder primacy.

The context for the contemporary shareholder primacy model has been corporate scandals. Over the last two decades in particular, corporate governance reform has been driven, in large part, by the desire to minimize the risk of corporate scandals. The idea here is that ‘good’ corporate governance should aim to reduce the risk of managerial misbehavior and, in doing so, maximize shareholder value. Identifying structures, processes and mechanisms for achieving these two goals has provided the impetus for much regulatory reform in this field over the last decade.

Starting with the Enron accounting fraud, corporate scandals have taken on a new significance—both in the media and politically—that was not previously the case.Footnote 14 Politicians are under much higher pressure to act against corporations, and the result has been that much of the post-2000 regulatory debate has been driven by the need to mitigate the risk of corporate misbehavior.

As such, the goal of much contemporary corporate governance reform has been to limit opportunities for managerial ‘misbehavior’.Footnote 15 ‘Misbehavior’ here means acting in any way that is detrimental to the shareholder-owners’ best interests. A corporate culture that eradicates—or at the very least minimizes—opportunities for misbehavior of any kind offers the best means to maximize shareholder value and is, therefore, seen as optimal.

According to this view, executives, managers, and other employees are understood to be motivated by self-interest and to have a selfish disregard for the negative consequences of their actions for investors (and society). Increasing shareholder control over other actors within the firm becomes the primary goal of corporate governance rules, and many requirements are imposed on firms to mitigate this agency risk.

There is a global consensus that investor confidence depends, in large part, on the existence of an accurate and useful corporate governance framework. Such an organizational structure traditionally focuses on four issues: (1) an accountable board of directors that supervises executives; (2) a range of internal control and monitoring processes; (3) transparent information disclosure about the financial performance of the company; and (4) measures designed to protect the interests of ‘minority’ shareholders. The overall goal? Maximizing shareholder value.

Consider the global rise of ‘independent director’ rules and the concept of an ‘independent board’. An independent board is usually understood as a corporate board that has a majority—or a significant presence—of ‘outside’ directors who have no affiliation with the firm’s top executives and have minimal—ideally, no—business dealings with the company. The aim? To minimize the risk of potential conflicts of interest. The rationale is that an independent board is best placed to provide meaningful oversight over other (‘inside’) board members and the firm’s senior executives-managers and, thus, reduces managerial opportunism-illegality. The benefit of this type of board is that it enhances control and results in an increase in shareholder value. It at least minimizes the risk of destructive managerial behavior that can have potentially catastrophic effects on shareholders. In turn, this results in a healthier investment environment.

If the corporate governance is ‘right’, shareholder value will naturally follow. Jack Welch—CEO of General Motors from 1981 to 2003 and widely viewed as a ‘shareholder value maximization’ evangelist—insisted after the financial crisis of 2008 that maximizing shareholder value should be viewed as an ‘outcome rather than a strategy’. This viewpoint implies that increased shareholder value will be a predictable ‘by-product’ of aligning the interests of executives-management with the interests of shareholders. In other words, if management acts opportunistically at the expense of shareholder value, everyone suffers the negative consequences of firm underperformance and possible bankruptcy.

3.2 The Unintended Effects of Corporate Governance

However, not everyone agrees with the view that pursuing shareholder value represents the best way of ensuring corporate success.Footnote 16 Over the last decade, a more skeptical view has emerged. Serial entrepreneurs, venture capitalists, futurists and business visionaries, in particular, have argued that a focus on maximizing shareholder value creates a corporate environment in which conservative decision-making, short-term profit, and formalistic compliance are prioritized. This is to the detriment of the corporation and its long-term prospects of building relevancy and being successful.

According to this view, increasing corporate executives’ accountability to shareholders and shareholder control over executives does not address the business needs of most firms. In fact, this approach may have the counterproductive effect of incentivizing a damaging emphasis on financial reporting and quarterly results. A myopic focus on maximizing shareholder value feeds an unhealthy short-term focus on firm share price and market valuations that obscures issues of innovation.Footnote 17 Shareholder value maximizations result in a preference to concentrate on the execution of a settled business model built around already existing and successful products or services. In these companies, executives with a knowledge of, and focus on, innovation and consumer experience—i.e., those individuals responsible for the initial success of a company and best placed to deliver relevancy—often find themselves marginalized from core decision-making processes.

Listed companies, in particular, are prone to putting too much emphasis on financial metrics, such as ‘return on net assets’ (RONA), return on capital deployed, and internal rate of return (IRR). Of course, it is essential to focus on financial metrics. However, one must realize that an emphasis on measures of quarterly earnings and short-term stock price performance can easily distract an organization from the vital business tasks of identifying strategies that can help a firm remain relevant over the medium to longer term.

In the shareholder primacy view, a firm’s employees comprise one group of marginalized stakeholders. This is problematic since companies need to take care of their employees, as they, unlike senior management, are directly responsible for the customer; and a strategy of building a business around the promotion of shareholder value can result in practices that run counter to the interests of employees. An obvious example would be the use of mass layoffs to balance the firm’s books in a firm in which executive performance is evaluated based solely on the firm’s stock price (i.e., balanced books = share price is secured = big executive bonus). In certain circumstances, laying off employees and reducing labor costs may be a natural mechanism to achieve strong quarterly performance.

However, a corporate environment in which mass layoffs are implemented to secure an increase or maintain the current level of the stock price can easily have a damaging effect on the firm’s culture. Apart from anything else, there seems to be something perverse about rewarding executives for the business decisions that (presumably) created the initial problems on the balance sheet and triggered the pressure to reduce labor costs.

Moreover, this model seems unlikely to result in the kind of corporate culture that will motivate employees or maximize opportunities for employee job satisfaction. Quite to the contrary, it seems likely to breed a culture of distrust between employees on the one hand and executives and managers on the other. And if keeping employees happy is the key to innovation, customer happiness and the long-term commercial success of a firm, then a corporation oriented around maximizing shareholder value is likely to fail.

Silicon Valley serial entrepreneur Steve Blank goes so far as to suggest that a ‘shareholder value maximization’ model built on financial metrics to measure business efficiency makes it extremely difficult for a company to retain the type of consumer-oriented focus that is critical to maintaining relevancy over the long term.Footnote 18 Consumers now demand constant innovation, rapid product evolution, and highly disruptive technologies.

One effect of this consumer demand is faster innovation cycles. To give a simple illustration: it took radio 38 years to reach 50 million users. It took television 13 years to achieve the same degree of market penetration. But the Internet and Facebook needed ‘only’ 4 and 2 years, respectively, to achieve the same number of users. Investing in potentially disruptive innovation is risky and demands a long-term focus. Emphasizing the importance of ‘making money’—i.e., profit for investors—in the short term merely encourages executives and managers to look for fast and easy payoffs. Such a mindset does nothing for the long-term prospects of a firm.

Moreover, rewarding such behavior means that companies end up being controlled and managed by ‘salespeople’ (with a focus on marketing), based on strong input from accountants (with a focus on financials and past performance) and strategy consultants (with a focus on structures and processes that increase ‘total returns to investors’).

Paradoxically, executives with a knowledge of, and focus on, products and consumer experience—i.e., individuals responsible for the initial success of a company and best placed to deliver relevancy—find themselves marginalized from core decisions. Steve Jobs described this risk very well when reflecting on his early experience with (and departure from) Apple:

The people that can make a company more successful are sales and marketing people. In addition, they end up running the companies. Moreover, the product people are driven out of decision-making forums. And the companies forget what it means to make great products. The product sensibility and product genius that brought a firm early success get rotted out by people running these companies who have no understanding of a good product versus a bad product.

Ironically, the shareholder primacy view sets a process of (inevitable) long-term decline into motion. For both Jobs and Blank, such a ‘customer-first approach’ is the key to creating a corporate environment that ensures relevancy for the long term.Footnote 19 This relevancy will then be reflected in continued commercial success. It will also contribute to the stimulating and exciting working environment that attracts (and then retains) the most talented executives, managers, and employees.

3.3 ‘New’ Corporate Governance

Recognition of these limitations of the shareholder primacy model has driven some recent trends in corporate governance that focus on encouraging stakeholders to take a more responsible ‘long-term’ approach. Two trends are highlighted here: (1) stewardship codes; and (2) measures aimed at promoting ‘sustainability’.

First, the recognition that a long-term focus needs to be added to the ‘corporate governance equation’ has resulted in the adoption of so-called ‘stewardship codes’ across multiple jurisdictions (see Table 2). What makes these codes distinctive is their attempt to create more engaged and responsible shareholders. These shareholders, particularly institutional investors, must be viewed as ‘stewards’ of a firm. Such stewards necessarily take a longer-term view of the firm and also embrace a more active role in the supervision of management issues.

Forcing shareholders, particularly institutional investors, to adopt a longer-term view when making their investments arguably leads to a more balanced corporate culture.Footnote 20 Policy discussion has focused on encouraging these institutional investors—who, compared to retail investors, tend to be sophisticated market actors—to take a more active role in firm governance. There is a consensus that firms can make strategic gains from such engagement. However, earlier studies on this issue have found that while some institutions spend time and resources on active ownership, a significant number of institutional investors have not actively engaged in the corporate governance of their portfolio companies.Footnote 21

Moreover, the recognition of the potential value of shareholder engagement seems to reflect the prevailing view that the recent financial crisis was, at least in part, caused by a lack of shareholder intervention. ‘Where were the shareholders?’ asked John Plender in a Financial Times article that he wrote in the early stages of the crisis.Footnote 22

To encourage a meaningful and constructive engagement, industries and countries have, therefore, promulgated and published so-called ‘stewardship codes’. As mentioned above, these codes attempt to create more responsible and purposeful investor engagement. In particular, they attempt to foster the view that institutional investors must be viewed as ‘stewards’ of a company, rather than as ‘investors’ in the narrow sense.

Rather than setting formal standards, in 2010, the UK regulator—the UK Financial Reporting Council—published the first country-based stewardship code.Footnote 23 The UK Stewardship Code sets out good practices for institutional investors seeking to engage with the board and management of listed companies and applies on a ‘comply or explain’ basis. Thus, institutional investors may either comply with it or not; but if not, they must explain why publicly. The Code is principles-based rather than rules-based and sets out recommendations rather than rules.

The Code principles state that institutional investors should: (1) publicly disclose their policy on how they will discharge their stewardship responsibilities; (2) have a robust policy for managing conflicts of interest in relation to stewardship that should be publicly disclosed; (3) monitor their investee companies; (4) establish clear guidelines on when and how they will escalate their stewardship activities; (5) be willing to act collectively with other investors where appropriate; (6) have a clear policy for voting and disclosure of voting activity; and (7) report periodically on their stewardship and voting activities.

Some other countries have developed or are in the process of developing stewardship codes, particularly in Europe, but also in Brazil, Canada, Japan, Malaysia, South Africa, South Korea and Thailand.

A second example of recent corporate governance reforms are initiatives that encourage firms to take a more ‘responsible’ and ‘sustainable’ approach to their activities.Footnote 24 Currently, the primary focus of such efforts is on disclosure and transparency (the one-way dissemination of information from the company to external actors, especially investors).

Increasingly, the public’s growing unease with corporate behavior drives these reform trends. We all recognize the power that corporations have in modern life, and many people now expect better standards from them. While corporations have colonized the public good, public space, and the public commons, their narrow focus on extracting value has generated mistrust and anti-corporate attitudes among many people. The result is that there is greater public demand for a broader view of the corporate mission than mere profit-seeking. This has triggered a new conversation about what is expected from companies and the company mission. The public increasingly demands this, particularly younger people (the prospective future ‘talent’ of any organization). Companies increasingly recognize this themselves, and many corporations have adjusted their behavior by, for example, spending their profits on investing in more sustainable and environmentally friendly research and development (R&D). Of course, this is done out of self-interest: companies recognize that if they do not do this, it will affect their long-term survival.

In spite of the short-term populist appeal of corporate governance initiatives that encourage ‘long-term’ thinking or corporate responsibility and sustainability, there are concerns that such initiatives might not work in the way that policymakers hoped or intended. Stewardship codes are an illustrative example of the risks. The potential benefits of these codes seem clear. Consider Japan, for example. Partly as a result of adopting a stewardship code (and other corporate governance reforms), Japan has risen in the Asian Corporate Governance Association rankings. More importantly, there is greater interest in Japanese firms among international, especially US, institutional investors.

But, is putting the onus on shareholders to be ‘more responsible’ a realistic or sensible move? Do we want policymakers to make shareholders more ‘active’? Mobilizing investors may lead firms’ executives and managers to ask the wrong questions about what needs to be done to ensure success. Rather than incentivizing a focus on innovation and relevancy, such measures seem to merely reinforce the centralized shareholder primacy view. Indeed, stewardship pressures still expose companies to an unhealthy focus on short-term dividends and share buybacks to please the stock market.

The focus on dividends and share buybacks makes it extremely difficult for a company to invest in innovations that are critical to maintaining relevancy over the long term. In a digital and networked age, the real question to ask management is: what are you doing to make our firm more relevant in dealing with current and future business opportunities and challenges? And the real question for regulators is: what kind of corporate governance is best placed to deliver the most innovative businesses for the twenty-first century?

There is an obvious problem with both of these approaches: although they may succeed in promoting long-term shareholder engagement or more sustainable behavior, they do little to encourage the kind of constant innovation that is necessary in a digital age. Instead, such codes seem to be a corrective measure designed to address problems created by earlier corporate governance measures (i.e., short-termism and a ‘bureaucratization’ of the corporate culture). As a secondary effect, these codes may result in more dynamic and innovative firm behavior, but this is not the primary goal of such measures; nor does it seem likely to be a direct effect. Stated bluntly: do these more recent developments in corporate governance actually help firms stay relevant in today’s highly competitive digital markets?

Another concern is the speed of regulatory change. Reform in this field of law now occurs so quickly that it merely creates a culture of formalistic compliance. New or additional corporate governance rules, guidelines, principles or codes increasingly meet with indifference, skepticism or even hostility, and there seems to be little doubt that many companies suffer from ‘compliance fatigue’. And even if such initiatives are on the agenda of a company’s next board meeting, the question remains whether they result in a genuine change in the governance and culture of the firm, particularly regarding the firm’s capacity to innovate. As such, the digital transformation and the rise of platforms remains a forgotten element in the contemporary discourse and practice of corporate governance.

4 ‘Platform Governance’

So, what can regulators do to help firms succeed in the digital transformation by operating as platforms?Footnote 25 One possible starting point might be to consider the likely evolution of platforms and the strategies necessary for building the successful platform of tomorrow. Regulatory measures—what we term ‘platform governance’—that are more closely aligned with the business needs of such firms could then be identified. The ‘disconnect’ that currently exists between ‘regulatory pressures’ and ‘business needs’ could then be mitigated to some degree.

In the following, we suggest three strategies that are crucial for any firm either considering entering the platform business or developing an existing platform. The structure and organization of the platform of the future will depend on the successful deployment of these three strategies.

It should be noted from the outset that there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ model for platforms. Platforms can take multiple forms, ranging from slightly ‘tweaked’ versions of traditional ‘centralized’ companies to blockchain-based ‘decentralized autonomous organizations’ (see Fig. 4). At one extreme are well known platforms such as Amazon and Netflix. In contrast, an example of a decentralized platform is Openbazaar, a peer-to-peer trading network that uses Bitcoin. The ‘best’ approach to platform design depends on the individualized circumstances of a particular business model and its goals. Every firm has to analyze and use these strategies to find the unique recipe for its platform to maximize creativity and opportunities for innovation.

4.1 Strategy 1: Leveraging New Technologies to Create ‘Community-Driven’ Organizations

New digital technologies have been central to the emergence and global expansion of platforms. Consider the following crucial technologies:

-

Cheaper and more powerful digital hardware (i.e., PCs and, more recently, smartphones).

-

Global communication networks and mass connectivity (i.e., the Internet).

-

Cloud-based storage of Big Data and automated algorithms that ‘match’ platform users.

These overlapping technological developments provide the foundation and infrastructure for platforms. Digital technology offers ‘peer-to-peer’ solutions and also provides users with the possibility of sharing reviews, experiences, and any other information. The technology that drives the platform also connects developers and creators on one side and users on the other. In this respect, all companies that wish to operate as platforms need to think and act ‘as if’ they are a technology company.

Several features of successful platforms are worth noting. First, the underlying technology on which a platform runs must be secure, safe and reliable for all of the platform’s users and participants. Second, it must be user-friendly and offer a continually updated and upgraded interface. The digital world changes fast, and new information must be readily available. People do not want to waste time, so it should not be too cumbersome (with clicks, registrations, etc.) to use the platform and its services. Third, the technology must offer users and participants ‘connectivity’, ‘choice’, and ‘convenience’. Nevertheless, it should also enable monetization, as well as analytical (including artificial intelligence), promotional (marketing), and creative activities.

Indeed, a platform needs to be easy for others to ‘plug into’. Platforms and their infrastructure need to enable quick and simple interactions between participants. After all, the ‘customer relationship’ with a platform can be brittle, and, as new platforms emerge, the competition for users intensifies. As such, platform builders must pay attention to the design of incentives, reputation systems, feedback mechanisms, and pricing models.

Data management is at the heart of successful platform ‘matchmaking’ and distinguishes platforms from other business models. The successful matchmaker collects data from platform participants and leverages that data to facilitate connections between groups of users.Footnote 26

As transaction facilitators, platforms help users find and compare content, products and services. What is interesting in this regard is that platforms help users make the ‘right’—or ‘better’—choices. Seamless online access to a platform, in combination with user reviews, has become as important to people’s choice processes as brand image or loyalty. As a result, branding matters much less than the delivery of reliable service and constant innovation in the range of services that the platform offers. Therefore, technology is central to the operation and lasting appeal (or ‘stickiness’) of platforms for all stakeholders, and continually planning for the arrival of near-future technologies becomes crucial. This requires constant vigilance, awareness of incoming innovations and a high degree of imagination regarding how such technologies can be deployed in a platform environment.

Consider one example of how constant innovation in the integration of newly developed technologies is central to building a successful platform: blockchain-based ‘tokens’. A platform can issue its own tokens as an integral part of the platform’s operations. These tokens can be thought of as a company-specific cryptocurrency that performs many functions and brings multiple benefits.

The issuance of these coins/tokens can be compared with a company’s loyalty program.Footnote 27 The tokens provide access to products, services, discounts and other perks and, thus, will help gather a community of participants, such as developers, investors, and consumers, on the platform. They tie individuals into the platform’s ecosystem, facilitating network effects. However, unlike a loyalty program, tokens have other benefits attached to them.

Most importantly, they offer liquidity. Platform participants can transfer them to other interested parties on crypto-exchanges or secondary markets. These parties could be the public or a more restricted and predefined group of people. This integrates the token (and platform) into the mainstream economy.Footnote 28 Finally, since the ‘owners’ of the tokens are not locked into the platform, the issuance of tokens can be a means to attract funding for the platform (without issuing shares).

Similar creativity will be required to incorporate multiple emerging technologies—such as robots/automation, artificial intelligence, machine learning, the Internet of Things, and nanotechnologies—into platform operations.

4.2 Strategy 2: Building an Open and Accessible Platform Culture

Having a platform ‘culture’ is probably the most important (but often misunderstood or neglected) strategy for developing a successful platform. A platform needs to embed an open and accessible corporate culture in every aspect of its operations and organization.

In this context, ‘open and accessible’ means that the platform and all of its participants need to clearly understand what and whom they are dealing with. For more decentralized platforms, this means, for instance, that its code and protocols must be ‘open source’ so that weaknesses and shortcoming can constantly be tested and updated (if necessary). A more centralized platform may not need to make its code public, but it does need to be ‘open’ about its processes and the inner-workings of its technology (code and algorithms).

More generally, a platform needs to offer an accessible, honest, and personal experience to participants. Participants must be able to verify the reputation of, and trust, other participants. Platforms must facilitate connections to a community of users that ‘matters’ to them. They must encourage user creativity and engagement (through social media, reviews, blogs, and, perhaps, loyalty coins). After all, a successful platform culture is about ensuring a strong and sustainable relationship between the platform and its participants: Are you constantly enticed to use the platform? Are you able to make ‘using the platform’ a routine, habitual part of your everyday life? And does the routinized use of the platform add value and offer inspiration? Stated slightly differently, the platform culture needs to ‘invite’ platform ‘participants’ on a meaningful digital journey. It should offer a flexible, unique, personalized experience that ‘kickstarts’ a ‘platform cycle’ of consuming, learning, sharing, creating, curating, networking and experimenting (see Fig. 5).

Central to this sort of open platform culture is communication. It is important to note that most of the issues that arise between a platform and its participants are the result of a platform’s failure to communicate properly (i.e., openly and honestly). For instance, YouTube’s difficulties with its content creators have tended to be the result of poor communication. Crucially, ‘smart’ platforms understand that communication is not a one-way process of information disclosure (from platform operators to platform users) but, instead, should entail a more engaged, responsive and open process that encourages a mutually productive dialogue.

Many alternative means can now be used for communicating within a platform’s ecosystem. For example, platform leaders can interact with participants via an annual letter. Such letters seem to work best when written in a personalized and honest style. Social media and other online media (such as blogs) are, of course, also becoming increasingly important as a forum for disclosing information about a company, both internally and externally. There are many new opportunities and possibilities for more creative forms of information dissemination and sharing.

A well-documented example of a company that has adopted this type of approach is Amazon. Jeff Bezos’ annual letters to investors are considered a ‘must-read’ for anyone with interest in Amazon (and platform companies).Footnote 29 What is perhaps most interesting is that these letters not only inform investors and other participants about the previous year’s performance and future developments and growth prospects, but also provide business advice and insights. It is not surprising that these letters attract enormous attention on social media. They have created significant hype, which makes the communication even more personalized, open, and effective.

But there is more. For a platform to work, a ‘best-idea-wins’ principle must be embedded in its culture. One company that is often cited for its success in creating this kind of open culture is Netflix. In 2009, its founder, Reed Hastings, pointed out that too many companies have ‘nice-sounding’ value statements, such as integrity, communication, respect, and excellence. However, he understood that these are often not what a company really values and, all too often, are just window dressing.

In a 124-page slide deck,Footnote 30 Hastings outlined that the dynamic of this employer-employee relationship needs to be changed. Moreover, the quality of the working experience and environment now matters so much more. Of particular importance are opportunities for learning and capacity building. As Hastings stated in the slide deck, ‘The actual company values, as opposed to the nice-sounding values, are shown by who gets rewarded, promoted, or let go’.

This forward-thinking approach to culture, which was recently updated, helps to attract talented people, as it offers them a much higher degree of freedom and responsibility. In the absence of this type of culture, the best young talent will leave.Footnote 31 Inside Netflix, it is all about context, not control. The result is that every Netflix employee is treated as an entrepreneur. Its ability to attract creators also shows that the open culture is in the DNA of Netflix. Thus, potential employees are attracted by the creative (and financial) freedom offered by the Netflix platform.

Finally, to successfully build a smart platform, leadership is essential. Business leaders should be visionary, entrepreneurial, and innovation-minded. They should understand the ‘platform dynamics’.

Take Netflix again. When Reed Hastings ‘let go’ his Head of Communications for repeated use of a racial slur, he showed the importance of leadership. In a memo to Netflix staff, he wrote: ‘I should have done more to use [a first incident] as a learning moment for everyone at Netflix about how painful and ugly that word is, and that it should not be used. I realize that my privilege has made me intellectualize or otherwise minimize race issues like this. I need to set a better example by learning and listening more, so I can be the leader we need’.

A company’s success in becoming a smart platform depends on its leadership and on its leader’s ability to listen and engage. Business leaders should have a thorough understanding of the ingredients that make a company a successful and smart platform.

The same goes for a platform’s directors.Footnote 32 Since their ability to add value in a digital age is beyond question, many more companies can be expected to appoint ‘digital technology people’ to the board of directors. This is a necessary step to deal with the digital challenges and opportunities in today’s business environment.

An example of a company that appointed ‘digital experience’ to its board of directors is The Walt Disney Company. Sheryl Sandberg (Facebook) and Jack Dorsey (Twitter and Square) were added to the Disney board to bring the requisite social media and technology expertise to the company. Such expertise was seen as ‘[e]xtremely valuable, given Disney’s strategic priorities, which include utilizing the latest technologies and platforms to reach more people and to enhance the relationship we have with Disney’s customers’.Footnote 33

Together, these examples illustrate the general point that the successful platform of the future understands the power of an open, engaged and ‘flat’ culture that encompasses all stakeholders in a platform.

4.3 Facilitating ‘Meaningful’ Platform Content

Platform content is also vital. After all, if the platform fails to deliver meaningful content to users, then it will fail. Yet it should be emphasized that the delivery of strong platform content is interrelated and overlaps with the other strategies of leveraging technology and building the right kind of platform culture.

As to content, we can be brief. The content (including products, services, and other ‘creative’ content) needs to be authentic. It must establish networks and connections that are crucial to the success of both the platform and its participants. These connections are important because they provide the platform and its participants with a sense of community that can then have a positive impact on the development of the platform, its participants, and future content.

Community insights are essential for all platform firms as they develop. The goal of such connectivity is to create a stronger platform culture that adds to the user experience and builds brand loyalty. Consumer commitment to a product or brand has a commercial value that firms can then leverage to their advantage in multiple ways.

There was a time when companies could develop and market their products without devoting much—if any—thought to connectivity. The possibilities for connected products—i.e., products that allow data to be exchanged between the product and its environment, manufacturer, user, and other devices or systems—were limited. But the emergence of network technologies has completely changed what is technically possible and what consumers now expect regarding connectivity.

Here, we can again refer to Walt Disney. The company was able to create a platform culture around its Star Wars movie The Force Awakens with ‘only’ limited resources. The movie’s teaser on YouTube generated 1.3 million Facebook interactions in the first hour after it had become available. Fans, discussing clues about the movie’s plot, posted 17,000 tweets per minute.

Finally, a ‘give-before-you-get’ principle prevails (as much as possible). And revenue models are often either ‘ad-supported’ or based on subscriptions that offer unlimited access and other perks.

The smart platform of tomorrow has all three strategies working in synergy (see Fig. 6). All platforms need to pursue this objective, and the goal of platform governance needs to be the identification of regulatory mechanisms that nudge firms in this direction.

4.4 Open Communication and Governance

As highlighted earlier, the more fluid and inclusive relationships that are now necessary in order for a firm to innovate—what we term ‘partnering for innovation’—presupposes a high degree of cooperation, loyalty and mutual trust, at least when compared to more control-oriented, directed and horizontal organizational forms. Open communication provides a mechanism for coordinating different stakeholders. Most obviously, open communication involves a different style of information dissemination and exchange that characterizes relationships between all actors in the firm. In particular, open communication is characterized by a more personalized approach to communication.

To begin with, open communication is not only about sharing information (the one-way dissemination of information from one part of the company to another, or from the company to external actors, most notably investors). Indeed, it encourages the building of an ongoing and constructive dialogue with other actors in the firm and the market, which can then have a significant impact on that company’s future performance. Moreover, open and ‘personalized’ communication is about respect (building trust and loyalty), but it is also about recognizing the material benefits that accrue from sharing. Thus, by embracing open communication, more inclusive and meaningful relationships among and between firm stakeholders can be forged.

The key idea behind open communication is that it fosters a sense of belonging and expands the pool and diversity of actors with a concrete involvement in key decision-making processes. What’s more, open communication is linked to various aspects of participation in, and responsibility for, decision making within an organization. The most innovative companies have acknowledged that they stand to benefit from a more open attitude towards both insiders and outsiders; such an attitude greatly expands the type of individuals responsible for guiding the direction of the company. In this way, open communication can create a powerful sense of participation and belonging that makes the corporate project more meaningful from the perspective of both insiders and outsiders—and also from the firm’s perspective.

Of course, adopting this kind of open and engaged communication strategy provides a company with other potential benefits. For example, open communication can allow firms to be better placed to make ‘smarter’ decisions. Similarly, firm ‘know-how’ will be enhanced, and problems will be dealt with more effectively. In addition, the firm will develop a more extensive and deeper network, retain more performance-related information necessary for planning, and offer a more collaborative and meaningful environment for all stakeholders. These are just some of the substantial benefits that a firm can enjoy when it embraces open communication and the more personal, inclusive relationships that such communication can facilitate.

If open communication is done properly, a whole ecosystem can emerge around the communication strategy of a firm. To understand the benefits of effective and open financial communication to stakeholders, consider the excitement surrounding Warren Buffet’s and Jeff Bezos’ annual letters to the shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway and Amazon, respectively. These examples show that information can be a resource to be exploited—via open communication—to the commercial advantage of a company.Footnote 34 The hype that can accompany the ‘event’ of disclosure can become an effective means to feed excitement and interest in the firm. This can make the company interesting and relevant for potential (and talented) employees, as well as for investors.

It is also important to have open communication strategies within the firm. Clearly, a focus on open communication involves a shift in how the role of the board of directors in a large firm is conceptualized. Currently, the dominant view is to treat the board mainly as the supervisors or monitors of the senior managers. As a result, the board tends to focus on controlling managerial misbehavior and monitoring the company’s past performance, compliance and sustainability, rather than on actively contributing to future performance. At several recent events, board members complained that more than 80% of the time at board meetings is now taken up with discussing monitoring and compliance issues.

It should be noted that many companies now recognize that this role is no longer sufficient and that the model of board ‘independence’ constitutes a missed opportunity. Instead, the more innovative twenty-first century firms, or those that desperately try to become one, include a diverse range of individuals who are expected to work in collaboration with the firm’s CEO and other senior managers. As mentioned earlier, the Walt Disney Company added Sheryl Sandberg (Facebook) and Jack Dorsey (Twitter and Square) to their board of directors for their social media and technology perspectives. Disney seems to understand that the directors help the firm stay relevant through their diverse perspectives. Such a diverse board of directors contributes to a more collaborative model of the relationship with management and ensures that these different perspectives are incorporated into the decision-making processes in a way that adds genuine value. The inherent uncertainty of identifying disruptive processes and technology explains why successful companies appoint such directors as ‘feedback providers’.

Recent research has raised a similar criticism of the effectiveness of independent directors. The degree to which such directors are effective—i.e., the degree to which they can ask difficult questions of other board members—seems to be contingent on the eradication of a structural bias towards the board members that appointed them in the first place. To what extent will ‘independent’ directors be willing or able to question the actions or decisions of those to whom they are, in some sense, obligated? Still, the degree to which these structural biases can be overcome or, at least, mitigated is the central challenge of implementing a corporate culture in which open communication is pervasive.Footnote 35

A related problem concerns firms that rely on technology to provide match-making services—i.e., bringing together individuals. Indeed, two obvious examples are Uber and Airbnb. Such firms stand or fall based on the ability of service providers and consumers to trust the system, and this willingness to trust is—crucially—contingent upon the willingness of participants to take part in and trust a system of reviews and ratings. Judgments about whether to enter a transaction are based upon the transaction history of the potential partner as evidenced by the rating system. If people decide not to participate—not to communicate—the system fails. What is interesting here is that these ‘match-making’ companies have introduced two-way rating systems through which service providers are rated by customers and customers by service providers.Footnote 36 Such a ‘checks-and-balances’ system helps build trust through a combination of open communication and algorithms put in place by the platform, and the result is that poor providers and/or customers get filtered out. In practice, the reliance on these technologies is becoming more important for other firms. So, for example, online retailers such as Amazon have made a rating system central to their online store, allowing potential consumers to make a decision about a good based on the experience of those who have already purchased it.Footnote 37

5 Conclusion

As we have seen, there is no doubt that the platform model is replacing traditional economic theories based on organizations, firms, and markets. The world of closed, centralized and hierarchical corporations is being displaced. The Internet, algorithms, online ratings, and artificial intelligence provide instant access to all kinds of information (with minimal effort). This provides almost unlimited opportunities for companies to bind users into their platform, to set up partnerships and to engage in constant innovation across multiple sectors of the economy. The success of platforms shows the enormous disruptive power of this new way of operating.

There is also considerable evidence that the most successful ‘new’ companies understand that trust, value and wealth are developed through the creation of smart platforms, instead of the static, hierarchical management of workers and products. Many established companies also recognize the opportunities of this new style of business but, nevertheless, continue to rely on existing structures, processes and procedures. It is hardly surprising that the shift to a digital age has proven enormously challenging for incumbents, as it requires a fundamental transformation of their organization and operations.

This brings us to the role of regulators and other policymakers. The new challenges raised by platform businesses requires a rethinking of the objectives and tools of regulating platforms. Of course, this is much easier said than done. After all, all levels of government are struggling to adapt to the fast-changing realities of a digital age. Rapid technological change makes it very difficult to identify and agree on an appropriate regulatory framework. At worst, regulations prohibit or otherwise limit the commercial exploitation of the opportunities created by constant technological innovation. Yet building on existing corporate governance frameworks—which don’t directly impinge on commercial opportunities—are also a part of the problem. Traditional models of corporate governance are an adaptation to a world of hierarchical and centralized organizations and often seem ill-suited to the organizational and business needs of platforms. ‘Corporate governance’ feeds a short-term, compliance-oriented and cautious corporate attitude that is counterproductive in a world in which companies need to be dynamic and continuously adapt to shifting technologies, markets, and evolving consumer demands.

The lesson? Regulators and policymakers should not intervene until they have developed a better understanding of their role in this new world of platforms. To this end, we must identify a unique form of ‘platform governance’ based on this better understanding of the needs and interests of platform-style businesses. As a first step, this paper has (1) identified the distinctive features of platforms; (2) described the disconnect that exists between platforms and corporate governance; and, (3) identified the core strategies that the successful platform of the future needs to adopt. The next step is to consider the specific regulatory mechanisms that can best incentivize firms to engage with and adopt these strategies. After all, those jurisdictions that are most successful in navigating this predicament and developing a new direction for corporate governance stand to be the primary beneficiaries of the digital transformation.

Notes

Parker and Van Alstyne (2018), p 3015.

Hagiu (2014), pp 1 et seq.

See Evans et al. (2006).

See Hagiu and Wright (2015).

See Kiron and Unruh (2018).

See Evans and Schmalensee (2016).

See Altman and Tushman (2017), p 3.

Parker et al. (2016), pp 205 et seq.

See Gluck et al. (1982).

See Brynjolfsson and McAfee (2014).

See Moss Kanter (2006).

See Wei and Lin (2016).

See Armour and McCahery (2006).

See FSB (2018).

See Bainbridge (2003).

See Ladika and Sautner (2013).

See Blank (2016).

See Blank (2013).

See Harford et al. (2014).

See Fisch et al. (2018).

See Plender (2015).

See FRC (2012).

See Eccles et al. (2012).

See European Commission (2018).

See Evans and Schmalensee (2016).

See Sandblock (2017).

See Li and Mann (2017).

See Bezoz (2017).

See Hastings (2011).

See Hoffman et al. (2014).

See Rickards and Grossman (2017).

See Walt Disney Company (2013).

Berman and Knight (2010).

See Erel et al. (2018).

See FTC (2016).

Sahoo et al. (2017).

References

Altman EJ, Tushman M (2017) Platforms, open/user innovation, and ecosystems: a strategic leadership perspective. Harvard Business School Organizational Behavior Unit working paper No 17-076. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2915213. Accessed 18 Jan 2019

Armour J, McCahery J (2006) After Enron: improving corporate law and modernising securities regulation in Europe and the US. Hart Publishing, Oxford

Bainbridge SM (2003) Director primacy: the means and ends of corporate governance. Nw Univ Law Rev 97(2):547–606

Berman K, Knight J (2010) Financial communication, Warren Buffett style. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2010/03/financial-communication-warren. Accessed 18 Jan 2019

Bezoz J (2017) 2017 Letter to shareholders. Amazon investor relations. http://phx.corporate-ir.net/phoenix.zhtml?c=97664&p=irol-reportsannual. Accessed 18 Jan 2019

Blank S (2013) Why the lean start-up changes everything. Harvard Business Review, May 2013. https://hbr.org/2013/05/why-the-lean-start-up-changes-everything. Accessed 18 Jan 2019

Blank S (2016) Intel disrupted: why large companies find it difficult to innovate, and what they can do about it. 23 June 2016. https://steveblank.com/2016/06/. Accessed 18 Jan 2019

Brynjolfsson E, McAfee A (2014) The second machine age: work, progress and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies. W.W Norton and Company, New York

Eccles RG, Ioannou I, Serafeim G (2012) The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Harvard Business School working paper. https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Publication%20Files/SSRN-id1964011_6791edac-7daa-4603-a220-4a0c6c7a3f7a.pdf. Accessed 18 Jan 2019

Erel I, Stern LH, Tan C, Weisbach MS (2018) Could machine learning help companies select better board directors? Fischer College of Business working paper No 2018-03-05. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3144080. Accessed 18 Jan 2019

European Commission (2018) Proposal for a Regulation on promoting fairness and transparency for business users online intermediation services. COM (2018) 238 final. https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/regulation-promoting-fairness-and-transparency-business-users-online-intermediation-services. Accessed 18 Jan 2019

Evans D, Schmalensee R (2016) Matchmakers: the new economics of platform businesses. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Evans DS, Hagiu A, Schmalensee R (2006) Invisible engines: how software platforms drive innovation and transform industries. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Fisch JE, Hamdani A, Davidoff Solomon S (2018) Passive investors. ECGI law working paper No 414/2018. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3192069. Accessed 18 Jan 2019

FRC (2012) The UK stewardship code. https://www.frc.org.uk/getattachment/d67933f9-ca38-4233-b603-3d24b2f62c5f/UK-Stewardship-Code-(September-2012).pdf. Accessed 18 Jan 2019

FSB (2018) Strengthening governance frameworks to mitigate misconduct risk: a toolkit for firms and supervisors. April 2018. http://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/P200418.pdf. Accessed 21 Jan 2019

FTC (2016) The ‘sharing’ economy: issues facing platforms, participants & regulators. An FTC staff report, November 2016

Gluck F, Kaufman S, Walleck SA (1982) The four phases of strategic management. J Bus Strat 2:9–21

Hagiu A (2014) Strategic decisions for multisided platforms. MIT Sloan Management Review, Winter 2014. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/strategic-decisions-for-multisided-platforms/. Accessed 18 Jan 2019

Hagiu A, Wright J (2015) Multi-sided platforms. Harvard Business School working paper, 15-037. https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=48249. Accessed 18 Jan 2019

Harford J, Kecskes A, Mansi S (2014) Do long-term investors improve corporate decision making? Working paper. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2505261. Accessed 18 Jan 2019

Hasting R (2011) Freedom & responsibility culture (version 1) slideshare. https://www.slideshare.net/reed2001/culture-2009. Accessed 18 January 2019

Hoffman R, Casnocha B, Yeh C (2014) The alliance: managing talent in the network age. Harvard Business Review Press, Cambridge

Kiron D, Unruh G (2018) Corporate ‘purpose’ is no substitute for good governance. MIT Sloan Management Review, April 2018. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/corporate-purpose-is-no-substitute-for-good-governance/. Accessed 18 Jan 2019

Ladika T, Sautner Z (2013) Managerial short-termism and investment: option vesting. Working paper, University of Amsterdam. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2286789. Accessed 18 Jan 2019

Li J, Mann W (2017) Initial coin offering and platform building. Working paper. https://www.jbs.cam.ac.uk/fileadmin/user_upload/research/centres/alternative-finance/downloads/2018-af-conference/paper-li.pdf. Accessed 18 Jan 2019

Moss Kanter R (2006) Innovation: the classic traps. Harvard Business Review, November 2006. https://hbr.org/2006/11/innovation-the-classic-traps. Accessed 18 Jan 2019

Parker G, Van Alstyne M (2018) Innovation, openness and platform control. Manag Sci 64(7):3015–3032

Parker GG, Van Alstyne MW, Choudary SP (2016) Platform revolution: how networked markets are transforming the economy and how to make them work for you. Norton, New York

Plender J (2015) Capitalism: money, morals and markets. Biteback Publishing, London

Rickards T, Grossman R (2017) The board of directors you need for a digital transformation. Harvard Business Review, 13 July 2017. https://hbr.org/2017/07/the-board-directors-you-need-for-a-digital-transformation. Accessed 18 Jan 2019

Rochet J, Tirole J (2003) Platform competition in two-sided markets. J Eur Econ Assoc 1(4):990–1029

Sahoo N, Srinivasan S, Dellarocas C (2017) The impact of online product reviews on product returns. Boston U. School of Management research paper No 2491276. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2491276. Accessed 18 Jan 2019

Sandblock (2017) White Pape. https://medium.com/sandblock/white-paper-update-revision-7-4dc072d8c14b. Accessed August 2018

Walt Disney Company (2013) Jack Dorsey elected to The Walt Disney Company Board of Directors. https://www.thewaltdisneycompany.com/jack-dorsey-elected-to-the-walt-disney-company-board-of-directors/. Accessed 18 Jan 2019

Wei Z, Lin M (2016) Market mechanisms in online peer-to-peer lending. Manag Sci 63(12):4236–4257

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Fenwick, M., McCahery, J.A. & Vermeulen, E.P.M. The End of ‘Corporate’ Governance: Hello ‘Platform’ Governance. Eur Bus Org Law Rev 20, 171–199 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40804-019-00137-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40804-019-00137-z

Keywords

- Blockchain

- Corporate governance

- Decentralization

- Digital transformation

- Disclosure

- Finance

- Organizations

- Platforms

- Technology

- Transparency