Abstract

Is there a correlation between the composition of the board of directors and the quantity and quality of information disclosed to the market, and in particular with respect to the disclosure of privileged, price-sensitive information? Our work examines this question with respect to the Italian Stock Exchange, also considering the role of minority-appointed directors in light of the Italian rules on slate voting that facilitate the election of directors by institutional investors and other minority shareholders. Based on a unique dataset of hand-picked data, we answer the basic research question in the affirmative. Independent directors and minority-appointed directors appear to have a positive impact on the amount and, to some extent, quality of disclosure, in particular if they have specific professional and educational qualifications (‘highly skilled directors’). We also tested if the market reacts to the information that is made public in order to consider the possible objection that outside directors simply require more disclosure of unimportant information. The event studies we conducted, however, indicate abnormal returns in the correspondence on the announcements we considered. The study sheds light on the role of independent and minority-appointed directors suggesting that they foster corporate transparency.

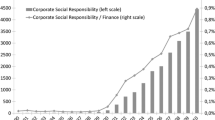

Source Consob (2018)

Source Consob (2018)

Source Consob (2018)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Marchetti et al. (2017).

Marchetti et al. (2017).

Regulation (EU) No. 596/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 on market abuse (market abuse regulation) and repealing Directive 2003/6/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and Commission Directives 2003/124/EC, 2003/125/EC and 2004/72/EC [2014] OJ L 173/1–61.

Directive 2014/57/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 on criminal sanctions for market abuse (market abuse directive) [2014] OJ L 173/179–189.

Aside from the well-known ‘co-determination’ system (Mitbestimmung) in Germany, that mandates the representation of employees on the board of supervisors of larger corporations, several jurisdictions, both in Europe and abroad, promote board diversity by providing for the appointment of independent and minority directors. Just to mention a few examples: in the UK, for premium listed companies, Listing Rule 9.2.2.ER requires that the election of any independent director must be approved by the ‘independent shareholders’ (i.e., shareholders different from the controlling shareholder). In Spain, Art. 243 of the Real Decreto Legislativo 1/2010 allows (minority) shareholders of sociedades anónimas to group together in order to appoint one or more directors. As for the US, independent directors have gained particular prominence in listed corporations, as stock listing standards, in conjunction with the Sarbanes–Oxley Act and the Dodd-Frank Act, require a majority of the board to be independent. Additionally, case law and regulatory evolution have facilitated proxy access, making it easier for small shareholders to indicate candidates for the board of directors. Other interesting examples are offered by Brazil and Israel: Art. 141 of the Brazilian Corporate Law provides for cumulative voting to ensure board representation for minority shareholders (voto múltiplo) and also reserves to minority shareholders that hold a minimum threshold of voting rights the appointment of a minority director, while in Israel the appointment of outside directors requires approval by the majority of the minority shareholders (see Art. 239, Israeli Corporate Law). For further references, see Davies and Hopt (2013); Davies et al. (2013); Gordon (2007); Recalde Castells et al. (2013); Salam and Prado (2011); OECD (2012).

Ex multis, Fama and Jensen (1983).

Beasley (1996).

Chen and Jaggi (2000).

Ho and Wong (2001).

Haniffa and Cooke (2002).

Eng and Mak (2003).

Armstrong et al. (2014).

Wang et al. (2015).

Schipper (1989) defines earnings management as ‘a purposeful intervention in the external financial reporting process, with the intent of obtaining some private gain (as opposed to, say, merely facilitating the neutral operation of the process) […].’ (emphasis added).

Quan and Li (2017).

Cao et al. (2014).

Inter alia, see Francis et al. (2002).

The Code requires the board of directors to evaluate the independence of its non-executive members ‘having regard more to the substance than to the form’ and provides an illustrative and non-exhaustive list of independence criteria. In particular, a director is normally not considered independent if (i) she controls, directly or indirectly, the issuer or is able to exercise a dominant influence over the issuer, or participates in a shareholders’ agreement through which one or more persons can exercise a control or dominant influence over the issuer; (ii) she is, or has been in the previous three fiscal years, a significant representative of the issuer, of a subsidiary having strategic relevance or of a company under common control with the issuer, or of a company controlling the issuer or able to exercise a considerable influence over the issuer, also jointly with others through a shareholders’ agreement; (iii) if she has, or has had in the previous fiscal year, directly or indirectly, a significant commercial, financial or professional relationship with the issuer, one of its subsidiaries, or any of its significant representatives, or with a subject who controls the issuer, or if she is, or has been in the previous three fiscal years, an employee of the above-mentioned subjects; (iv) if she receives, or has received in the previous three fiscal years, from the issuer or a subsidiary or holding company of the issuer, a significant additional remuneration compared to its fixed remuneration, also in the form of participation in incentive plans linked to the company’s performance, including stock option plans; (v) if she was a director of the issuer for more than 9 years in the last twelve years; (vi) if she is an executive director of another company in which an executive director of the issuer holds the office of director; (vii) if she is shareholder or quotaholder or director of a legal entity belonging to the same network as the company appointed for the auditing of the issuer; (viii) if she is a close relative of a person who is in any of the positions mentioned above. See generally Regoli (2008).

Assonime, Emittenti Titoli S.p.A. (2018), pp 34–35, 185, Table 51. The criterion that is more frequently not applied is the 9-year limit to the tenure of a director as a condition to be qualified as independent (considering that, under Italian law, the board is generally appointed every 3 years).

See Calvosa and Rossi (2013), pp 13 et seq.

See also Cerved (2018).

See Linciano et al. (2017).

See Linciano et al. (2017).

See Marchetti (2007), pp 143 et seq.

See, e.g., Ventoruzzo (2012).

Ventoruzzo (2017), p 14.

To be more precise, additional limitations might apply to primary insiders and might derive from contractual obligations, but the general framework is the one briefly described in the text.

Art. 17(4) MAR. See Moloney (2014), pp 730 et seq.

The definition of inside information has been the focus of several cases decided by the European Court of Justice. See infra in the text for a discussion of the relevant decisions. For a discussion of the notion of inside information, also in a comparative perspective, see Ventoruzzo (2014).

See generally Moloney (2014), pp 722–723.

Consob (2017).

The rationale might be that the mere knowledge of an event affecting volatility might allow to speculate in derivative instruments: see ECJ Case C-628/13 Lafonta v. Autorité des marchés financiers, ECLI:EU:C:2015:162. On this decision see Klöhn (2015).

Cass. 16 October 2017, no. 24310.

Cass. 14 February 2018, no. 3577.

Key Developments provides structured summaries of material news and events that may affect the market value of securities. It monitors over 100 types of disclosures including executive changes, M&A rumours, changes in corporate guidance, delayed filing. This database is also used by Cao et al. (2017) as a source of a firm’s disclosure.

Glaum et al. (2013).

See Haw et al. (2004).

Lang and Lundholm (1996).

Kothari et al. (2009).

Petersen (2009).

Jiang et al. (2013).

Matsunaga and Yeung (2008).

Jiang, Wan and Zhao (2015).

The reader should be aware that in no way do we believe that a more formally educated and/or professionally qualified individual is a ‘better’ director. We have no doubts, to speak about our own profession, that a very successful and accomplished academic can be an utterly awful director, and a person who started working early cutting her teeth ‘on the street’, without a long formal education and lacking any specific professional qualification, can be an excellent board member. More simply, our aim is to test whether those personal characteristics might have an impact on disclosure. We hope that the labels we picked for short, ‘high skilled’ and ‘low skilled’, do not detract the reader from the substance of our hypothesis or are not interpreted as expressing a value judgment.

The two SDIRs we use to collect privileged disclosures are emarketstorage and 1info.

See Francis et al. (2002).

References

Alvaro S, Mollo G, Siciliano G (2012) Il voto di lista per la rappresentanza di azionisti di minoranza nell’organo di amministrazione delle società quotate, Quaderno Giuridico, No 1. Consob, Rome

Armstrong CS, Core JE, Guay WR (2014) Do independent directors cause improvements in firm transparency? J Financ Econ 113(3):383–403

Assonime, Emittenti Titoli S.p.A. (2018) La Corporate Governance in Italia: autodisciplina, remunerazioni e comply-or-explain (anno 2017). Note e Studi No 2/2018. http://www.assonime.it/_layouts/15/Assonime.CustomAction/GetPdfToUrl.aspx?. http://www.assonime.it/attivita-editoriale/studi/Documents/Note%20e%20Studi%202%202018.pdf. Accessed 10 June 2018

Beasley MS (1996) An empirical analysis of the relation between the board of director composition and financial statement fraud. Account Rev 71:443–465

Belcredi M, Caprio L (2015) Amministratori di minoranza e amministratori indipendenti: stato dell’arte e proposte evolutive. In: Mollo G (ed) Atti dei seminari celebrativi per i 40 anni dall’istituzione della Commissione Nazionale per le Società e la Borsa, vol 9. Consob, Rome

Belcredi M, Bozzi S, Di Noia C (2013) Board elections and shareholders activism: the Italian experiment. In: Belcredi M, Ferrarini G (eds) Boards and shareholders in European listed companies. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 365–421

Brickley JA, James CM (1987) The takeover market, corporate board composition, and ownership structure: the case of banking. J Law Econ 30(1):161–180

Bushee BJ, Noe CF (2000) Corporate disclosure practices, institutional investors, and stock return volatility. J Account Res 38:171–202

Calvosa L, Rossi S (2013) Gli equilibri di genere negli organi di amministrazione e controllo delle imprese. Osservatorio Dir Civ Comm 2:3–33

Cao Y, Dhaliwal D, Li Z, Yang YG (2014) Are all independent directors equally informed? Evidence based on their trading returns and social networks. Manag Sci 61(4):795–813

Cao Y, Myers LA, Tsang A, Yang YG (2017) Management forecasts and the cost of equity capital: international evidence. Rev Account Stud 22(2):791–838

Castells AR, León Sanz F, Latorre Chiner N (2013) Corporate boards in Spain. In: Davies P, Hopt KJ, Nowak R, Van Solinge G (eds) Corporate boards in law and practice: a comparative analysis in Europe. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 549–615

Cerved (2018) Le donne al vertice delle società italiane. http://know.cerved.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CERVED_LE-DONNE-AL-VERTICE.pdf. Accessed 20 June 2018

Chen CJP, Jaggi B (2000) Association between independent non-executive directors, family control and financial disclosures in Hong Kong. J Account Public Policy 19(4–5):285–310

Chow C, Wong-Boren A (1987) Voluntary financial disclosure by Mexican corporations. Account Rev 62(2):533–541

Consiglio Nazionale dei Dottori Commercialisti e degli Esperti Contabili (2017) Disclosure di informazioni non finanziarie. https://commercialisti.it. Accessed 20 June 2018

Consob (2017) Gestione delle informazioni privilegiate. http://www.consob.it/documents/46180/46181/LG_Gest_Inf_Priv_20171013.pdf/28cc9d88-f517-4a68-be85-c63ecabc2584. Accessed 20 June 2018

Consob (2018) Report on corporate governance of Italian listed companies—statistics and analyses. http://www.consob.it/documents/46180/46181/rcg2018.pdf/549286f4-907e-427c-9fdf-926386140479. Accessed 9 Dec 2019

Cooke TE (1989) Disclosure in the corporate annual report of Swedish companies. Account Bus Res 19(Spring):113–122

Courtis JK (1979) Annual report disclosure in New Zealand: analysis of selected corporate attributes. Research Study. University of New England, Armidale

Davies P, Hopt KJ (2013) Corporate boards in Europe—accountability and convergence. Am J Comp Law 61:301–376

Davies P, Hopt KJ, Nowak R, Van Solinge G (2013) Corporate boards in law and practice: a cross-country analysis in Europe. In: Davies P, Hopt KJ, Nowak R, Van Solinge G (eds) Corporate boards in law and practice: a comparative analysis in Europe. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 3–115

Depoers F (2000) A cost benefit study of voluntary disclosure: some empirical evidence from French listed companies. Eur Account Rev 9(2):245–263

Di Noia C, Gargantini M (2012) Issuers at midstream: disclosure of multistage events in the current and in the proposed EU market abuse regime. Eur Co Financ Law Rev 9(4):484–529

Eng L, Mak YT (2003) Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure. J Account Public Policy 22(4):325–345

Enriques L, Gilotta S (2015) Disclosure and financial market regulation. In: Moloney N, Ferran E, Payne J (eds) The Oxford handbook of financial regulation. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 512–536

Erhardt NL, Werbel JD, Shrader CB (2003) Board of director diversity and firm financial performance. Corp Gov Int Rev 11(2):102–111

ESMA (2016) MAR Guidelines. Delay in the disclosure of inside information, 2016/1478. https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/2016-1478_mar_guidelines_-_legitimate_interests.pdf. Accessed 20 June 2018

ESMA (2017) MAR Guidelines. Information relating to commodity derivatives markets or related spot markets for the purpose of the definition of inside information on commodity derivatives, 2016/1480. https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/esma-2016-1480_mar_guidelines_on_commodity_derivatives.pdf. Accessed 20 June 2018

Fama EF, Jensen MC (1983) Separation of ownership and control. J Law Econ 26(2):301–325

Fan JP, Wong TJ (2002) Corporate ownership structure and the informativeness of accounting earnings in East Asia. J Account Econ 33(3):401–425

Francis J, Schipper K, Vincent L (2002) Expanded disclosures and the increased usefulness of earnings announcements. Account Rev 77(3):515–546

Gilotta S (2012) Trasparenza e riservatezza nella società quotata. Giuffrè, Milan

Glaum M, Baetge J, Grothe A, Oberdörster T (2013) Introduction of international accounting standards, disclosure quality and accuracy of analysts’ earnings forecasts. Eur Account Rev 22(1):79–116

Gordon JN (2007) The rise of independent directors in the United States, 1950–2005: of shareholder value and stock market prices. Stanf Law Rev 59:1465–1568

Guglielmetti R (2018) La dichiarazione sulle informazioni non finanziarie: ruoli e responsabilità degli organi aziendali. Riv Dott Comm 55–89

Haniffa RM, Cooke TE (2002) Culture, corporate governance and disclosure in Malaysian corporations. Abacus 38(3):317–349

Hansen JL (2010) Insider dealing defined: the EU Court’s decision in Spector Photo Group. Eur Co Law 7(3):98–105

Hansen JL (2016) Say when: when must an issuer disclose inside information?. University of Copenhagen Faculty of Law Legal Studies Research Paper No 2016-28; Nordic & European Company Law Research Paper Series No 16-03. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2795993. Accessed 20 June 2018

Haw IM, Hu B, Hwang LS, Wu W (2004) Ultimate ownership, income management, and legal and extra-legal institutions. J Account Res 42(2):423–462

Healy PM, Palepu KG (2001) Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: a review of the empirical disclosure literature. J Account Econ 31(1–3):405–440

Heflin FL, Shaw KW, Wild JJ (2005) Disclosure policy and market liquidity: impact of depth quotes and order sizes. Contemp Account Res 22(4):829–865

Hellgardt A (2013) The notion of inside information in the Market Abuse Directive: Geltl. Common Mark Law Rev 50(3):861–874

Ho SSM, Wong KS (2001) A study of corporate disclosure practice and effectiveness. Hong Kong J Int Financ Manag Account 12(1):75–102

Hoskin RE, Hughes JS, Ricks WE (1986) Evidence on the incremental information content of additional firm disclosures made concurrently with earnings. J Account Res 24:1–32

Hossain M, Perera MHB, Rahman AR (1995) Voluntary disclosure in the annual reports of New Zealand companies. J Int Financ Manag Account 6(1):69–87

Jiang F, Zhu B, Huang J (2013) CEO’s financial experience and earnings management. J Multinatl Financ Manag 23(3):134–145

Jiang W, Wan H, Zhao S (2015) Reputation concerns of independent directors: evidence from individual director voting. Rev Financ Stud 29(3):655–696

Klöhn L (2010) The European insider trading regulation after Spector Photo Group. Eur Co Financ Law Rev 7(2):347–366

Klöhn L (2015) Inside information without an incentive to trade? What’s at stake in ‘Lafonta v. AMF’. Cap Mark Law J 10(2):162–180

Kosnik RD (1990) Effects of board demography and directors’ incentives on corporate greenmail decisions. Acad Manag J 33(1):129–150

Kothari SP, Shu S, Wysocki PD (2009) Do managers withhold bad news? J Account Res 47(1):241–276

Krause H, Brellochs M (2013) Insider trading and the disclosure of inside information after Geltl v Daimler—a comparative analysis of the ECJ decision in the Geltl v Daimler case with a view to the future of European Market Abuse Regulation. Cap Mark Law J 8(3):283–299

Lang MH, Lundholm RJ (1996) Corporate disclosure policy and analyst behavior. Account Rev 71(4):467–492

Lang M, Ready J, Wilson W (2006) Earnings management and cross listing: are reconciled earnings comparable to US earnings? J Account Econ 42:255–283

Lapointe-Antunes P, Cormier D, Magnan M, Gay-Angers S (2006) On the relationship between voluntary disclosure, earnings smoothing and the value-relevance of earnings: the case of Switzerland. Eur Account Rev 15(4):465–505

Lee CI, Rosenstein S, Rangan N, Davidson III (1992) Board composition and shareholder wealth: the case of management buyouts. Financ Manag 21(1):58–72

Leuz C (2006) Cross listing, bonding and firms’ reporting incentives: a discussion of Lang, Raedy and Wilson (2006). J Account Econ 42(1–2):285–299

Leuz C, Verrecchia RE (2000) The economic consequences of increased disclosure. J Account Res 38(Suppl):91–124

Leuz C, Nanda D, Wysocki P (2003) Earnings management and investor protection: an international comparison. J Financ Econ 69:505–527

Linciano N, Ciavarella A, Signoretti R, Della Libera E (2017) Report on corporate governance of Italian listed companies. Consob, Statistics and analyses. http://www.consob.it/documents/46180/46181/rcg2017.pdf/7846a42b-1688-4f45-8437-40aceaa2b0e3. Accessed 20 June 2018

Macrì E (2010) Informazioni privilegiate e disclosure. Giappichelli, Turin

Marchetti P (2007) I controlli sull’informazione finanziaria. In: Balzarini P, Carcano G, Ventoruzzo M (eds) La società per azioni oggi. Atti del convegno internazionale di studi tenutosi a Venezia, vol 1. Giuffrè, Milan, pp 143–160

Marchetti P, Siciliano G, Ventoruzzo M (2017) Dissenting directors. Eur Bus Org Law Rev 18(4):659–700

Matsunaga SR, Yeung PE (2008) Evidence on the impact of a CEO’s financial experience on the quality of the firm’s financial reports and disclosures. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1014097. Accessed 20 June 2018

Meek GK, Roberts CB, Gray SJ (1995) Factors influencing voluntary annual report disclosures by US, UK and continental European multinational corporations. J Int Bus Stud 26(3):555–572

Moloney N (2014) EU securities and financial markets regulation, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Montalenti P (2013) ‘Disclosure’ e riservatezza nei mercati finanziari: problemi aperti. Analisi Giur Econ 12:245–254

OECD (2012) Board member nomination and election. OECD Publishing. http://www.oecd.org/daf/ca/BoardMemberNominationElection2012.pdf. Accessed 20 June 2018

Petersen MA (2009) Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: comparing approaches. Rev Financ Stud 22(1):435–480

Quan Y, Li S (2017) Are academic independent directors punished more severely when they engage in violations? China J Account Res 10(1):71–86

Raffournier B (1995) The determinants of voluntary financial disclosure by Swiss listed companies. Eur Account Rev 4(2):261–280

Regoli D (2006) Gli amministratori indipendenti. In: Abbadessa P, Portale GB (eds) Il nuovo diritto delle società. Liber amicorum Gian Franco Campobasso, vol 2. UTET, Turin, pp 385–438

Regoli D (2008) Gli amministratori indipendenti tra fonti private e fonti pubbliche e statutali. Riv Soc 53:382–408

Richter MS Jr (2016) Article 147-ter TUF. In: Abbadessa P, Portale GB (eds) Le Società per Azioni, vol 2. Codice Civile e Norme Complementari. Giuffrè, Milan, pp 4190–4210

Salam BM, Prado VM (2011) Legal protection of minority shareholders of listed corporations in Brazil: brief history, legal structure and empirical evidence. J Civ Law Stud 4:147–185

Schipper K (1989) Earnings management. Account Horiz 3(4):91–102

Ventoruzzo M (2012) Recesso e valore della partecipazione nelle società di capitali. Giuffrè, Milan

Ventoruzzo M (2014) Comparing insider trading in the United States and in the European Union: history and recent developments. Eur Co Financ Law Rev 11(4):554–593

Ventoruzzo M (2017) The concept of insider dealing. In: Ventoruzzo M, Mock S (eds) Market abuse regulation. Commentary and annotated guide. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 13–31

Ventoruzzo M, Picciau C (2017) Article 7: Inside information. In: Ventoruzzo M, Mock S (eds) Market abuse regulation. Commentary and annotated guide. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 175–207

Wallace RSO, Naser K, Mora A (1994) The relationship between the comprehensiveness of corporate annual reports and firm characteristics in Spain. Account Bus Res 25(97):41–53

Wang C, Xie F, Zhu M (2015) Industry expertise of independent directors and board monitoring. J Financ Quant Anal 50(5):929–962

Weisbach MS (1988) Outside directors and CEO turnover. J Financ Econ 20:431–460

Welker M (1995) Disclosure policy, information asymmetry, and liquidity in equity markets. Contemp Account Res 11(2):801–827

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Angelo Borselli and Maria Lucia Passador for excellent research assistance. We also thank Alessandro Delledonne for providing institutional details about privileged information. Massimo Menchini read an earlier draft of this work and offered useful comments; while Duccio Regoli shared several ideas on the role of independent directors with the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Empirical Definition of the Variables and Sources

Appendix: Empirical Definition of the Variables and Sources

Variables | Definition | Sources |

|---|---|---|

disclosure | Natural log of one plus the total number of press releases for firm i at year t | KeyDevelopment |

ind_dir | Natural log of one plus independent directors over board members for firm i at year t | Corporate Governance Report |

for_sales | Percentage of foreign sales over total sales for firm i at year t | Datastream |

us_listed | 1 if firm i in year t has shares listed on United States stock markets | Datastream |

concentration | Natural log one plus of HH index using relevant ownerships data of firm i at year t | Consob |

size | Natural log of one plus total assets for firm i at year t | Compustat Global |

roa | Natural log of one plus return on assets for firm i at year t | Compustat Global |

ret_vol | Natural log of one plus standard deviation of firm i’s daily returns in year t | Datastream |

min_dir | Natural log of one plus % minority independent directors for firm i at year t | Corporate Governance Relation |

pages | Natural log of one plus pages in privileged information for firm i at year t | SDIR (1info, emarketstorage) |

info_priv | 1 if firm i reports privileged information | SDIR (1info, emarketstorage) |

Year | Fiscal years end as reported in Compustat Global | Compustat Global |

Industry | 2-digit sic codes | Compustat Global |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marchetti, P., Siciliano, G. & Ventoruzzo, M. Disclosing Directors. Eur Bus Org Law Rev 21, 219–251 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40804-019-00172-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40804-019-00172-w