Abstract

In the last decade, financial regulations have focused on issues posed by systemic risk. The derivatives market has been the subject of structural reforms which have involved both the post-trade—Regulation (EU) No. 648/2012 (‘EMIR’)—and the trading phase—Directive 2014/65/EU (‘MiFID II’) and Regulation (EU) No. 600/2014 (‘MiFIR’). In particular, the post-crisis regulation is characterized by the increasing role of the EU authorities both as a supervisor and as a regulator. The paper focuses on the role of ESMA in light of its new intervention powers. This paper analyses the regulations on over-the-counter derivatives introduced in Europe, with the goal of underlining the costs and benefits of this approach. To fully achieve its objective, the paper proposes, in the first section, a logical path that starts from an overview of the regulatory response to the crisis; then, in the second section, it focuses on ESMA’s growing role in light of the recent reforms. The third section points out the strengths and weaknesses of the law-making process with a particular reference to a highly technical topic. Finally, the analysis concludes by speculating on the potential ‘Brexit’ impact on the ESMA’s reform proposal, due to the role played by financial institutions and the activism of interested Member States.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Regulation (EU) No. 648/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 July 2012 on OTC derivatives, central counterparties and trade repositories [2012] OJ L201/1.

Directive 2014/65/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 May 2014 on markets in financial instruments and amending Directive 2002/92/EC and Directive 2011/61/EU [2014] OJ L173/349.

Regulation (EU) No. 600/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 May 2014 on markets in financial instruments and amending Regulation (EU) No 648/2012 [2014] OJ L173/84.

Tafara (2012), pp xi–xiv.

The regulatory agenda was set out in European Commission, Regulating Financial Services for sustainable Growth, 2 June 2010, COM(2010) 301 final. Among the scholars, in this sense, see Moloney (2012), p 115. Concerning the regulatory agenda, on the US side there is the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act and in the EU there are the regulations and directives on rating agencies, alternative investment fund managers, market infrastructures and OTC derivatives (EMIR), and the measures on short selling and the ban on credit default swaps (‘CDS’). For an analysis, see Moloney (2011c), pp 523–525; on short selling see Avgouleas (2011), pp 71 et seq.

According to Art. 10, para. 3, EMIR, a derivative contract is for a hedging purpose when it is ‘objectively measurable as reducing risks directly relating to the commercial activity or treasury financing activity of the non-financial counterparty or of that group’.

Cf. Arts. 10 and 11 Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No. 149/2013 [2013] OJ L52/11. In particular, for commodity derivatives the notional fixed threshold is € 3 billion.

On its website, ESMA will publish which derivatives are subject to the trading obligation, at which venue and from what date onwards (Art. 34).

Moloney (2011a), p 52.

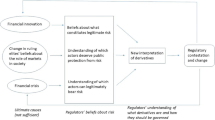

Black (2005), pp 1–15. The author precisely describes a range of different levels of ‘regulatory innovations’ (pp 8–11). The third level is about the ‘paradigm shift’ which means ‘changes in the cognitive and normative framework of the regulatory regime’ that determine the relevant transformation of regulatory instruments or institutions.

Moloney (2012), p 116. The author distinguishes three levels of changes. The first is a change in the ‘setting of regulation’—technical changes that involved rules and practices—which do not vary the regulatory status quo. The second level concerns changes to the institutional structures and the nature of regulatory intervention (e.g., soft and hard law). The third level is about the shift of the paradigm illustrated by Black (2005) which determines a reorganization of the ‘policy goal’ of regulations.

See Regulation (EU) No. 1095/2010 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 November 2010 establishing a European Supervisory Authority (European Securities and Markets Authority), amending Decision No. 716/2009/EC and repealing Commission Decision 2009/77/EC [2010] OJ L331/84 (hereinafter, ‘ESMA Regulation’), Art. 1(5) and Arts. 18–32.

Moloney (2011a), p 79.

Moloney (2007), pp 367 et seq.

See Sciarrone and Grossule (2017), pp 463-466.

It is worth noting that, when the physical agricultural markets are seriously affected—see Art. 42.2(f)—the competent national financial authorities have to properly consult public bodies that are competent for the physical agricultural markets in compliance with Council Regulation (EC) No. 1234/2007 of 22 October 2007 establishing a common organization of agricultural markets and on specific provisions for certain agricultural products (Single CMO Regulation) [2007] OJ L299/1.

See also Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No. 567/2017 [2017] OJ L87/90, Arts. 19–21.

Art. 39, MiFIR, specifies the task of market monitoring. In accordance with Art. 9(2) of the ESMA Regulation, ESMA shall monitor the market for financial instruments which are marketed, distributed or sold in the Union. NCAs are competent within their Member States.

Moloney (2012), pp 186 et seq.

Moloney (2015), p 761.

Cf. Art. 40(2)(a, b, c). It is worth noting that, in the case of commodity derivatives, when the physical agricultural markets are seriously affected—see Art. 40(3)(f)—ESMA has to properly consult with public bodies that are competent for the physical agricultural markets in compliance with the Single CMO Regulation.

In this sense, see Art. 40(8), MiFIR; the criteria and factors to be taken into account by ESMA are: (a) the degree of complexity of a financial instrument and the relation to the type of client it is marketed and sold; (b) the size or notional value of an issuance of financial instruments; (c) the degree of innovation of a financial instrument, an activity or practice; (d) the leverage that a financial instrument or practice provides.

Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No. 591/2017 of 1 December 2016 supplementing Directive 2014/65/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council with regard to regulatory technical standards for the application of position limits to commodity derivatives (RTS 21) [2017] OJ L87/479. As it is specifically detailed in RTS 2, NCAs must set limits based on the methodology developed by ESMA. Always in accordance with this methodology, NCAs have the power to review and reset position limits if significant market changes occur (e.g., in delivery supply or in open interest) on the basis of new market dynamics (Art. 57(4)).

As a consequence, ESMA can take action in accordance with its powers under Art. 17 of the ESMA Regulation.

The information that ESMA can request concerns the size and purpose of a position or the exposure entered into via a derivative. See Arts. 45(1) ((a), (b) and (c)) and 45(2), MiFIR. Moreover, in such exceptional cases, NCAs can also impose a strengthened regime of position limits, where the action is objectively justified and proportionate, taking into account the liquidity and the orderly functioning of the specific market (Art. 57(13)).

Even if ESMA is not mandated under MiFID II to develop technical standards in respect of this requirement and, therefore, position management controls applied by trading venues are not discussed further in the Discussion Paper, ESMA’s view is that this regime will operate in tandem with position limits set by NCAs. ESMA, Discussion paper MiFID II/MiFIR, 22 May 2014 (ESMA/2014/548), pp 406, 414; Moloney (2014), pp 535–538.

See Regulation (EU) No. 513/2011 amending Regulation (EC) No. 1060/2009 on credit rating agencies [2011] OJ L145/30. The CRA market represents a small section of the financial market but it was a major development for ESMA that for the first time has been empowered with direct supervision.

See also, Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No. 571/2017 supplementing MiFID II on the authorisation, organisational requirements and publication of transactions for data reporting services providers [2017] OJ L87/126 and Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No. 590/2017 supplementing MiFIR with regard to the reporting of transactions to competent authorities [2017] OJ L87/449. Avgouleas and Ferrarini (2018), p 61.

Busch (2018), p 36.

European Commission, Explanatory Memorandum EMIR Commission Proposal, 13 June 2017, COM(2017) 331 final, pp 3–4.

Due to EMIR Art. 88, ESMA has published a list of third-country central counterparties that are recognized as offering services and activities in the Union (7 January 2019 last update ESMA70-152-348). See also EMIR Arts. 75–76.

Given the highly technical aspects of the derivatives regulation, the EU legislator has conferred a wide range of powers to ESMA and to the NCAs also with regard to the regulatory issue. This strategy, though, gives rise to an important question related to the nature of the rules (RTS/ITS) issued especially by ESMA which, actually, is not only technical but also has political significance with all the well-known consequences for accountability.

This point of view has always met a certain degree of consensus for such regulatory processes as ‘scientific knowledge (technique) is everywhere the same’. In this sense see Loya and Boli (1999), p 188; the authors underline how often private organization reflects this idea. The most common expressions are: ‘based on international consensus among experts in the field […]’ or ‘the best available combination of technical skills and background experience […]’.

Buthe and Mattli (2011), pp 12 et seq.

On this topic, see Scott et al. (2011), pp 1 et seq.

This is a very debated topic especially in the US and UK; for an in-depth analysis see Biggins and Scott (2012), pp 311 et seq.

In this sense, Partnoy (2010), p 293 is emblematic. The author describes the law-making process as: ‘The legislative process has sometimes been compared to sausage-making; in the case of derivatives, the sausage makers were actually writing the law. The role of Congress was simply to look over the shoulders of the financial lobby, and nod’.

In addition to EMIR, the 2014/65/EU (cf. MiFID II) Directive and Regulation (EU) No. 600/2014 (cf. MiFIR) were approved: measures that modify the previous MiFID discipline. A discipline has been introduced that restricts short selling with particular restrictions on CDSs on sovereign debt securities (Regulation (EU) No. 236/2012 on short selling and certain aspects of credit default swaps [2012] OJ L86/1).

The legislation adopted only in response to the crisis events has resulted in a large critical movement. In the literature, in general see Ribstein (2003a), p 77; in relation to the Sarbanes–Oxley Act, see Ribstein (2003b), p 299; very critical is R. Romano (2005), pp 1521 et seq., where the author proposes a procedure that contrasts this phenomenon. Related to the Dodd–Frank Act, see Bainbridge (2011), pp 1779 et seq.

It is clear that the mere fact of approving a reform involves immediate costs for the operators involved. In addition to this, the reform phases are a period of disciplinary uncertainty, with the additional risk that the incumbent can undermine the acquired income positions; on this point, see Ferran (2012b), p 18: ‘[…] It characterizes the political economy as a terrain populated with entrepreneurial actors, with firms as key players, all seeking to advance their interests within existing rules and institutions that complement and reinforce each other’.

Hertig (2012), p 321.

To deepen these dynamics, referring in particular to the EU (cf. The Lamfalussy process), see Ferran (2004), pp 61 et seq.; Moloney (2008), pp 1009 et seq.; Dorn (2011), pp 35 et seq., highlights the need to implement democratic controls on the legislative procedure for financial regulation, criticizing the current law-making process. The author underlines: ‘the current de facto “independence” of financial market regulators allows them to network globally yet privately, to negotiate on the basis of market demands (each national regulator championing its home industry) and to coverage their rules accordingly—producing common blind spots, systemic vulnerabilities and heightened potential for global crisis’. Regarding accountability issues of independent authority, see Lastra and Shams (2001), p 167. For an in-depth analysis on comitology in the EU see Harlow (2002), p 32; related to the law-making process in the EU, see Moloney (2014), pp 845–894.

OTC derivative agreements are opaque and their potential financial consequences are often unknown. See Armour et al. (2016), p 470; the authors underline ‘the extreme opacity of OTC derivatives also pose information problems for dealers’ shareholders, counterparties and other creditors. Specifically, the size, complexity, and opacity of dealers’ derivatives portfolios can make it difficult for these institutions to meaningfully evaluate the financial condition of these institutions’.

Ibid., pp 470–471. There are relevant asymmetries of information between dealers and their clients. Moreover, derivatives, on the one hand, often mitigate counterparty credit and other risks while, on the other, they can increase financial instability.

On this aspect, even though referring to MiFID, see Ferrarini and Recine (2006), pp 235 et seq.

For an analysis of public consultation on MiFID II, European Commission, Public Consultation, Review of the Market in Financial Instruments Directive, 8 December 2010, http://ec.europa.eu/finance/consultations/2010/mifid/docs/consultation_paper_en.pdf (Accessed 17 April 2019).

Coffee Jr. (2012), p 311. The author introduces the ‘Regulatory Sine Curve’ theory according to which the intensity of regulatory action is not constant: it grows after the crisis and decreases with the return to normal market conditions.

EMIR, for example, empowers ESMA on 24 occasions. The implementation of these detailed technical standards is essential for the effectiveness of the new discipline. See Lannoo and Valiante (2012), p 2. The Dodd-Frank Act presents similar weaknesses, defined as ‘a skeletal structure that has few affirmative commands’ by Coffee Jr. (2012), p 351.

Referring to the Dodd-Frank Act, Coffee Jr. (2012), p 311 states: ‘Such administrative softening (or even abandonment) of legislative enactments may be even more likely in the case of the Dodd-Frank Act, because (1) the prospective costs to the financial industry are higher; (2) the Dodd–Frank Act has no natural allies among the major political players who usually support “reform” legislation applicable to the financial markets; and (3) the Dodd–Frank Act is even more dependent on administrative implementation and rule-making’.

Coffee Jr. (2012), p 352. The author adds another element of weakness: the financial industry would be able to obtain further benefits from using the Courts against administrative measures more than it would against legislative measures.

This dynamic is deepened by Hertig (2012), pp 321 et seq.

Moloney (2008), pp 1071 et seq. discusses this topic with particular reference to EU committees within the Lamfalussy process.

On the need to make the financial markets law ‘democratic’, see Dorn (2011), p 35; Moloney (2008) emphasizes the accountability risk, recalling the need for greater transparency in decision-making and greater dialectics in the consultation process. In particular, the author also focuses on the analysis of these issues which has led European institutions to involve the European Parliament in the decision-making process. Bovens (2007), pp 447 et seq. However, he does not believe that democratic control over the financial market regulatory process is left almost exclusively to consultation procedures.

Black (2011), pp 3 et seq.

On this issue, see Ferran (2012b), pp 17, 20–21 et seq. After a brief description of the two large and diverse capitalist patterns within the EU—a ‘liberal market economy’ characterized by a strong financial market relevance (referring to the United Kingdom system), and the other ‘coordinated market economy’, characterized by long-term non-market relationships (e.g. Germany)—the author explains: ‘Starting from the rational assumption that countries will act so as to protect and promote their national interest, theory postulates the stance that countries adopt with respect to the new regulatory initiatives will be influenced by their determination of whether those initiatives are likely to sustain or undermine the comparative institutional advantages of their nation’s economy’. Finally, the author adds that the integration of the financial markets in the EU is also known as the ‘systems battle’.

Mügge (2013), p 460.

FSA-HM Treasury (2009), pp 11 et seq.

Schieffer (2011), pp 22–25. There are two models for the organization of the clearing service: the vertical system (‘vertical silo’)—where trading, clearing and settlement are housed in a singular infrastructure, and the horizontal model in which CCPs clear products for various exchanges and execution facilities. In theory, vertical silos are more efficient from the operational point of view, conversely it is less transparent as regards costs. In fact, it is a closed system that allows it to internalize all revenues obtainable in the different phases from trading to clearing. Deutche Borse, Intercontinental Exchange and CME, for example, have adopted the vertical silos. The horizontal model (adopted, for example, by LCH.Cleatnet and Options Clearing Corporation—OCC) encourages competition between CCPs and supports new market entrants by providing an accessible clearing structure. In contrast, this system is less efficient and more costly from on operational point of view, due to the presence of a multitude of trading venues.

The compromise was analysed by Grant (2011); Ferran (2012b), pp 38–39. The author highlights the case of the ban on ‘naked’ CDS on sovereign debt securities. The rule, desired by the continental countries, provides for the loosening of the restriction that could have negative effects on both the sovereign bond market and the CDS market. This last caveat, albeit limited in such cases, represents a compromise in favour of the British position.

See ‘Feedback statement on the public consultation on the operations of the European Supervisory Authorities having taken place from 21 March to 16 May 2017’, Brussels 20 June 2017, p 5, available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/2017-esas-operations-summary-of-responses_en.pdf.

Arts. 10–11, Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No. 149/2013, supra n. 8.

On capital and margin requirements and the issues posed by exceptions, see also Financial Stability Board (2010), pp 27 et seq. For an in-depth analysis of revenue distributions, Hertig (2012), p 335: ‘[…] The implication: the exemption is driven by rent distribution consideration, giving priority to the revenues of non-financial users and their banks over clearing house’.

Lanoo and Valiante (2012), p 2; Table 1 summarizes this study schematically. The number of articles of regulation increased from 72 to 91; the number of words increased from 19,465 to 43,101.

Lanoo and Valiante (2012), p 2: ‘The exemption for pension funds is regarded as the major success of lobbying efforts with the European Parliament, but it does not apply in the US’. See in particular, recitals from 26 to 29 and Art. 89 EMIR.

European Commission, Proposal for Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council, Amending Regulation (EU) No. 1093/2010 establishing a European Supervisory Authority (European Banking Authority); Regulation (EU) No. 1094/2010 establishing a European Supervisory Authority (European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority); Regulation (EU) No. 1095/2010 establishing a European Supervisory Authority (European Securities and Markets Authority); Regulation (EU) No. 345/2013 on European venture capital funds; Regulation (EU) No 346/2013 on European social entrepreneurship funds; Regulation (EU) No. 600/2014 on markets in financial instruments; Regulation (EU) 2015/760 on European long-term investment funds; Regulation (EU) 2016/1011 on indices used as benchmarks in financial instruments and financial contracts or to measure the performance of investment funds; and Regulation (EU) 2017/1129 on the prospectus to be published when securities are offered to the public or admitted to trading on a regulated market, 20 September 2017, COM(2017) 536 final.

See Art. 47(3) and Art. 29a, ESAs Proposal.

Art. 45-45a and 47, ESAs Proposal.

Avgouleas and Ferrarini (2018), p 57.

European Commission, Public Consultation on the Operations of European Supervisory Authorities, 21 March 2017, available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/consultations/public-consultation-operations-european-supervisory-authorities_en#about-this-consultation.

See the Feedback statement on the public consultation on the operations of the European Supervisory Authorities having taken place from 21 March to 16 May 2017, Brussels 20 June 2017, p 5, supra n. 65.

European Commission, Public Consultation, supra n. 75, and Busch (2018), p 34.

European Commission, Explanatory Memorandum in Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Regulation (EU) No. 1095/2010 establishing a European Supervisory Authority (European Securities and Markets Authority) and amending Regulation (EU) No. 648/2012 as regards the procedures and authorities involved for the authorisation of CCPs and requirements for the recognition of third-country CCPs, 13 June 2017, COM(2017) 331 final, p 5.

‘The Commission Reflection Paper on the deepening of the Economic and Monetary Union suggests that a review of the EU supervisory framework—in particular of the European Securities and Markets Authority (“ESMA”)—should deliver the first steps towards such a single supervisor by 2019’. European Commission, Proposal for a Regulation on the European Parliament and the Council, supra n. 78, p 2.

Cf. Art. 21a(5) sub a) and b), Art. 44b(1) EMIR proposal and Art. 6(1a) ESMA regulation in the EMIR proposal. On the new powers of the CCP Executive Session see Busch (2018), pp 45–46.

The UK is the major centre for market-based funding in the EU (in particular in alternative funding) through ‘business angels’, venture capital, and private equity investment, see European Commission, European Financial Stability and Integration Review 2016, p 26, available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/system/files/efsir-2016-25042016_en.pdf. The UK was also one the main contributors to developing the MiFID II/MiFIR package and UCITS (Undertakings for the collective investment of transferable securities) and AIMFD (Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive regimes. See Moloney (2017), pp 116–117.

European Court of Justice 13 June 1958, Case 9/56, Meroni v. High Authority [1957-1958] ECR 133. Cf. also, European Court of Justice 2 May 2006, Case C-217/04, UK v. EU Parliament and Council [2006] ECR I-3789. In general, on issues posed by the Meroni doctrine, see Hofmann, Rowe and Turk (2011), p 587. See also, Pelkmans and Simoncini (2014), p 2. For an in-depth analysis in the legal literature see Moloney (2011a), p 73 and Moloney (2011b), p 220.

See European Commission, Building an European Capital Markets Union, Green Paper, 18 February 2015, COM(2015) 63 final.

Germany is unlikely to support a significant increase in ESMA’s power. In this way, Ireland and Luxembourg, very active in the post-Brexit market, prefer to maintain national discretion; see Moloney (2017), p 125 and fn. 92.

References

Armour J, Awrey D, Davies P, Enriques L, Goordon JN, Mayer C, Payne J (2016) Principles of financial regulation. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Avgouleas E (2011) The vexed issue of short sales regulation when prohibition is inefficient and disclosure insufficient. In: Moloney N, Alexander K (eds) Law reform and financial markets. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 71–110

Avgouleas E (2015) Regulating financial innovation. In: Moloney N, Ferran E, Payne J (eds) The Oxford handbook of financial regulation. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 659–689

Avgouleas E, Ferrarini G (2018) A single listing authority and securities regulator for the CMU and the future of ESMA. In: Busch D, Ferrarini G (eds) Capital Market Union in Europe. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 55–77

Bainbridge M (2011) Dodd–Frank: quack federal corporate governance round II. Minn Law Rev 45:1779–1821

Biggins J, Scott C (2012) Public-private relations in a transnational private regulatory regime: ISDA, the state and OTC derivatives market reform. EBOR 13:309–346

Black J (2005) What is regulatory innovation? In: Black J, Lodge M, Thatcher M (eds) regulatory innovation. A comparative analysis. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 1–15

Black J (2011) The rise, fall and fate of principles-based regulation. In: Moloney N, Alexander K (eds) Law reform and financial markets. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 3–34

Bovens M (2007) Analysing and assessing accountability: a conceptual framework. Eur Law J 13:447–468

Busch D (2018) A stronger role for the European supervisory authorithies in the EU27. In: Busch D, Avgouleas E, Ferrarini G (eds) Capital Markets Union in Europe. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 28–54

Buthe T, Mattli W (2011) The new global rulers. The privatization of regulation in the world economy. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Coffee JC Jr (2012) The political economy of Dodd–Frank. In: Ferran E, Moloney N, Hill JG, Coffee JC Jr (eds) The regulatory aftermath of the global financial crisis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 301–371

Dorn N (2011) Policy stances in financial market regulation: market rapture, club rules or democracy? In: Moloney N, Alexander K (eds) Law reform and financial markets. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 35–68

Ferran E (2004) Building an EU securities market. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Ferran E (2012a) Understanding the new institutional architecture of EU financial market supervision. In: Wymeersch E, Hopt KJ, Ferrarini G (eds) Financial regulation and supervision. A post crisis analysis. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 111–158

Ferran E (2012b) Where in the world is the EU going? In: Ferran E, Moloney N, Hill JG, Coffee JC Jr (eds) The regulatory aftermath of the global financial crisis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 1–107

Ferran E (2016) The UK as a third country in EU financial services regulation. University of Cambridge Faculty of Law Research Paper No 47/2016. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2845374. Accessed 17 Apr 2019

Ferrarini G, Recine F (2006) The MiFID and internalisation. In: Ferrarini G, Wymeersch E (eds) Investor protection in Europe. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 235–270

Financial Stability Board (2010) Implementing OTC derivatives market reforms. 25 October 2010. http://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/r_101025.pdf. Accessed 17 Apr 2019

FSA-HM Treasury (2009) Reforming OTC derivative markets: a UK perspective. December. http://www.fsa.gov.uk/pubs/other/reform_otc_derivatives.pdf. Accessed 22 Feb 2018

Grant J (2011) Quick view: UK gets best of compromise on EMIR. Financial Times, October 2011. https://www.ft.com/content/b51054d8-eeaf-11e0-959a-00144feab49a. Accessed 22 Feb 2018

Harlow C (2002) Accountability in European Union. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Hertig G (2012) Post-financial crisis trading and clearing reforms in the EU: a story of interest groups with magnified voice. In: Wymeersch E, Hopt KJ, Ferrarini G (eds) Financial regulation and supervision. A post crisis analysis. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 321–336

Hofmann CH, Rowe GC, Turk AH (2011) Administrative law and policy of the European Union. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Lannoo K, Valiante D (2012) Prospects and challenges of a pan-European post-trade infrastructure. ECMI Policy Brief No 20. November 2012 https://www.ceps.eu/publications/prospects-and-challenges-pan-european-post-trade-infrastructure. Accessed 29 Apr 2019

Lastra RM, Shams H (2001) Public accountability in financial sector. In: Ferran E, Goodhart C (eds) Regulating financial services and markets in 21st century. Hart Publishing, Portland, pp 165–188

Loya TA, Boli J (1999) Standardization in the word polity: technical rationality over power. In: Boli J, Thomas G (eds) Constructing world culture: international non-governmental organization since 1875. Stanford University Press, Stanford, pp 169–197

Lucantoni P (2014) Central counterparties and trade repositories in post-trading infrastructure under EMIR Regulation on OTC derivatives. J Int Bank Law Regul 29:681–688

Macey J (1992–1993) Corporate law and corporate governance: a contractual perspective. J Corp Law 18:185–211

Moloney N (2007) Law making risks in EC financial market regulation after the financial services action plan. In: Weatherill S (ed) Better regulation. Hart Publishing, Oxford, pp 321–367

Moloney N (2008) EC securities regulation. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Moloney N (2011a) The European Securities and Markets Authority and institutional design for the EU financial market—a tale of two competences: part (1) Rule-making. EBOR 12:41–86

Moloney N (2011b) The European Securities and Markets Authority and institutional design for the EU financial market—a tale of two competences: part (2) Rules in action. EBOR 12:177–225

Moloney N (2011c) Reform or revolution? The financial crisis, EU financial markets law, and the European Securities and Markets Authority. Int Comp Law Q 60:521–534

Moloney N (2012) The legacy effects of the financial crisis on regulatory design in the EU. In: Ferran E, Moloney N, Hill JG, Coffee JC Jr (eds) The regulatory aftermath of the global financial crisis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 111–202

Moloney N (2014) EU securities and financial markets regulation. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Moloney N (2015) Regulating the retail markets. In: Moloney N, Ferran E, Payne J (eds) The Oxford handbook of financial regulation. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 736–768

Moloney N (2016) International financial governance, the EU and Brexit, the agencification of EU financial governance and the implication. EBOR 17:451–480

Moloney N (2017) Brexit and EU financial governance: business as usual or institutional change. Eur Law Rev 42:112–128

Moloney N (2018) EU financial governance after Brexit: the raise of technocracy and absorption of the UK’s withdrawal. In: Alexander K, Barnard C, Ferran E, Lang A, Moloney N (eds) Brexit and financial services. Hart Publishing, Oxford, pp 61–113

Mügge D (2011) The European presence in global financial governance: a principal agent. J Eur Public Policy 18:383–402

Mügge D (2013) The political economy of Europeanized financial regulation. J Eur Public Policy 20:458–470

Partnoy F (2010) Infectious greed: how deceit and risk corrupted the financial markets. Profile Books, London

Pelkmans J, Simonicini M (2014) Mellowing Meroni: how Esma can help build the single market. CEPS commentary 18 February 2018. https://www.ceps.eu/publications/mellowing-meroni-how-esma-can-help-build-single-market. Accessed 20 June 2018

Quaglia L (2012) The ‘old’ and ‘new’ politics of financial services regulation in the EU. New Polit Econ 17:515–535

Quaglia L (2014) The European Union and global financial regulation. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Ribstein LE (2003a) Bubble laws. Houst Law Rev 40:77–98

Ribstein LE (2003b) International implications of Sarbanes-Oxley Act: raising the rent on US law. J Corp Law Stud 3:299–328

Romano R (2005) The Sarbanes–Oxley Act and the making of quack corporate governance. Yale Law J 114:1521–1611

Schieffer J (2011) Axis or open access? Markit Mag 13:22–25

Sciarrone A, Grossule E (2017) Commodity derivatives. In: Busch D, Ferrarini G (eds) Regulation of the EU financial markets: MiFID II and MiFIR. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 439–467

Scott C, Cafaggi F, Senden L (2011) The conceptual and constitutional challenge of transnational private regulation. J Law Soc 38:1–19

Tafara E (2012) Observation about crisis and reform (foreword). In: Ferran E, Moloney N, Hill JG, Coffee JC Jr (eds) The regulatory aftermath of the global financial crisis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp xi–xxvi

Wymeersch E (2010) The reforms of the European supervisory system—an overview. Eur Co Financ Law Rev 7:240–265

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Professor Andrea Perrone for his precious comments and to Professor Danny Busch for discussions on this topic during my Visiting Period at the Financial Institute—Radboud University, Nijmegen. This article is the outcome of a research period at the University of Pavia under the supervision of Professor Paolo Benazzo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grossule, E. Risks and Benefits of the Increasing Role of ESMA: A Perspective from the OTC Derivatives Regulation in the Brexit Period. Eur Bus Org Law Rev 21, 393–414 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40804-019-00147-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40804-019-00147-x