Abstract

This paper studies the relationship between the innovation performance of European regions and their resilience. By exploiting a novel dataset that includes patents and trademarks at the regional (NUTS2) level for the 2008–2016 period, the paper addresses two research questions: (1) are innovative regions more resilient? (2) which type of innovation is more conducive to resilience? We frame the relationship between resilience and innovation within the Schumpeterian notion of innovation as a ‘creative response in history’. Overall, we find that a stronger performance in innovation is associated with a better performance in employment both during and in the aftermarket of the 2008 financial crisis. We argue that learning capabilities built over time by regions make them more effective in adapting and recovering during major shocks. While the crisis may have created an opportunity for less developed regions to move ahead, this opportunity has in fact been grasped mainly by those already having a strong regional system of innovation in place.

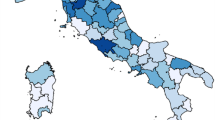

Source: Authors’ elaboration Eurostat data

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See also the European Commission Communication COM (2017) 479 final titled “Investing in a smart, innovative and sustainable Industry A renewed EU Industrial Policy Strategy”, available here.

In principle there are several other control variables that can affect our two measures of resilience, such as for instance the degree of internationalization. However, we cannot include variables that can explain at the same time innovation, which is our main explanatory variable. Part of these effects we expect to be captured by country dummies.

Actually, Bottazzi and Peri (2003) suggest that due to the tacit nature of knowledge spillover can be very localized, according to their estimations, on average, spillover operates on a range of about 300 km.

References

Acs, Z. J., & Audretsch, D. B. (1989). Patents as a measure of innovative activity. Kyklos, 42(2), 171–180.

Antonelli, C. (2015). Innovation as a creative response. A reappraisal of the Schumpeterian legacy. History of Economic Ideas, 23(2), 99–118.

Antonelli, C., & Scellato, G. (2011). Out-of-equilibrium profit and innovation. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 20(5), 405–421.

Antonioli, D., Bianchi, A., Mazzanti, M., Montresor, S., & Pini, P. (2013). Economic crisis and innovation strategies. Evidence from Italian firm-level data. Economia politica, 1, 33–68.

Antonioli, D., & Montresor, S. (2019). Innovation persistence in times of crisis: An analysis of Italian firms. Small Business Economics, 1–26.

Archibugi, D., Filippetti, A., & Frenz, M. (2013). Economic crisis and innovation: Is destruction prevailing over accumulation? Research Policy, 42, 303–314.

Bassi, F., & Durand, C. (2018). Crisis in the European monetary union: A core-periphery perspective. Economia Politica, 35, 251–256.

Boschma, R. (2015). Towards an evolutionary perspective on regional resilience. Regional Studies, 49, 733–751.

Bottazzi, L., & Peri, G. (2003). Innovation and spillovers in regions: Evidence from European patent data. European Economic Review, 47(4), 687–710.

Briguglio, L., Cordina, G., Farrugia, N., & Vella, S. (2009). Economic vulnerability and resilience: Concepts and measurements. Oxford Development Studies, 37, 229–247.

Bristow, G., & Healy, A. (2018). Innovation and regional economic resilience: An exploratory analysis. The Annals of Regional Science, 60, 265–284.

Bristow, G.I., Healy, A., Norris, L., Wink, R., Kafkalas, G., Kakderi, C., Espenberg, K., Varblane, U., Sepp, V., Sagan, I., & Masik, G. (2014). ECR2. Economic crisis: Regional economic resilience. Final report of the ESPON 2013 programme, ESPON & Cardiff University.

Cainelli, G., Ganau, R., & Modica, M. (2019a). Industrial relatedness and regional resilience in the European union. Papers in Regional Science, 98, 755–778.

Cainelli, G., Ganau, R., & Modica, M. (2019b). Does related variety affect regional resilience? New evidence from Italy. The Annals of Regional Science, 62(3), 657–680.

Clark, J., Huang, H.-I., & Walsh, J. P. (2010). A typology of “Innovation Districts”: What it means for regional resilience. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3, 121–137.

Combes, P. P. (2000). Economic structure and local growth: France, 1984–1993. Journal of Urban Economics, 47(3), 329–355.

Coniglio, N. D., Lagravinese, R., & Vurchio, D. (2016). Production sophisticatedness and growth: Evidence from Italian provinces before and during the crisis, 1997–2013. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 9, 423–442.

Crescenzi, R., Gagliardi, L., & Percoco, M. (2013). The ‘Bright’ side of social capital: How ‘Bridging’ makes Italian provinces more innovative. In R. Crescenzi & M. Percoco (Eds.), Geography, institutions and regional economic performance (pp. 143–164). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Crescenzi, R., Pietrobelli, C., & Rabellotti, R. (2016). Regional strategic assets and the location strategies of emerging countries’ multinationals in Europe. European Planning Studies, 24, 645–667.

Dijkstra, L., Garcilazo, E., & McCann, P. (2015). The effects of the global financial crisis on European regions and cities. Journal of Economic Geography, 15(5), 935–949.

Doran, J., & Fingleton, B. (2014). Economic shocks and growth: Spatio-temporal perspectives on Europe’s economies in a time of crisis. Papers in Regional Science, 93, S137–S165.

Faggian, A., Gemmiti, R., Jaquet, T., & Santini, I. (2018). Regional economic resilience: The experience of the Italian local labor systems. The Annals of Regional Science, 60, 393–410.

Filippetti, A., & Archibugi, D. (2011). ‘Innovation in times of crisis: National system of innovation. Structure and Demand’, Research Policy, 40, 179–192.

Filippetti, A., Guy, F., & Iammarino, S. (2019). Regional disparities in the effect of training on employment. Regional Studies, 53, 217–230.

Filippetti, A., & Peyrache, A. (2015). Labour productivity and technology gap in European regions: A conditional frontier approach. Regional Studies, 49, 532–554.

Frenken, K., Van Oort, F., & Verburg, T. (2007). Related variety, unrelated variety and regional economic growth. Regional Studies, 41, 685–697.

Giannakis, E., & Bruggeman, A. (2017). Determinants of regional resilience to economic crisis: A European perspective. European Planning Studies, 25, 1394–1415.

Giannini, V., Iacobucci, D., & Perugini, F. (2019). Local variety and innovation performance in the EU textile and clothing industry. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 28(8), 841–857.

Holling, C. S. (1973). Resilience and stability of ecological system. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 4(1), 1–23.

Hu, X., & Hassink, R. (2017). Exploring adaptation and adaptability in uneven economic resilience: A tale of two Chinese mining regions. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 10(3), 527–541.

Iammarino, S., & McCann, P. (2006). ‘The structure and evolution of industrial clusters: Transactions technology and knowledge spillovers. Research policy, 35, 1018–1036.

Iammarino, S., Rodriguez-Pose, A., & Storper, M. (2017). Why regional development matters for Europe’s economic future. Working Papers—European Commission, WP 07/2017.

Jacobs, J. (1969). The life of cities. New York: Random House.

Jaffe, A. B., Trajtenberg, M., & Henderson, R. (1993). Geographic localization of knowledge spillovers as evidenced by patent citations. The Quarterly journal of Economics, 108, 577–598.

Krugman, P. (1991). History and industry location: The case of the manufacturing belt. The American Economic Review, 81, 80–83.

Lagravinese, R. (2014). Crisi Economiche e Resilienza Regionale. EyesReg–Giornale di Scienze Regionali, 4, 48–55.

Lagravinese, R. (2015). Economic crisis and rising gaps North–South: Evidence from the Italian regions. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8, 331–342.

Lee, N. (2014). Grim down South? The determinants of unemployment increases in british cities in the 2008–2009 recession. Regional Studies, 48, 1761–1778.

March, J. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2, 71–87.

Martin, R. (2011). The local geographies of the financial crisis: From the housing bubble to economic recession and beyond. Journal of Economic Geography, 11, 587–618.

Martin, R. (2012). Regional economic resilience, hysteresis and recessionary shocks. Journal of Economic Geography, 12, 1–32.

Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2006). Path dependence and regional economic evolution. Journal of Economic Geography, 6, 395–437.

Martin, R., Sunley, P., & Tyler, P. (2015). Local growth evolutions: Recession, resilience and recovery. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8, 141–148.

Marzinotto, B. (2017). Euro area macroeconomic imbalances and their asymmetric reversal: The link between financial integration and income inequality. Economia Politica, 34, 83–104.

McCann, P., & Ortega-Argilés, R. (2013). Smart specialization, regional growth and applications to European union cohesion policy. Regional Studies, 49, 1291–1302.

Metcalfe, J. S., & Ramlogan, R. (2006). Creative destruction and the measurement of productivity change. Revue de l’OFCE, 5, 373–397.

Morgan, K. (2007). The learning region: Institutions, innovation and regional renewal. Regional Studies, 41, S147–S159.

Ortiz, J., & Salas Fumás, V. (2020). Technological innovation and the demand for labor by firms in expansion and recession. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 29(4), 417–440.

Palaskas, T., Psycharis, Y., Rovolis, A., & Stoforos, C. (2015). The asymmetrical impact of the economic crisis on unemployment and welfare in Greek urban economies. Journal of Economic Geography, 15(5), 973–1007.

Piscitello, L. (2004). Corporate diversification, coherence and economic performance. Industrial and Corporate Change, 13, 757–787.

Quatraro, F. (2009). Innovation, structural change and productivity growth: Evidence from Italian regions, 1980–2003. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 33, 1001–1022.

Sarra, A., Di Berardino, C., & Quaglione, D. (2019). Deindustrialization and the technological intensity of manufacturing subsystems in the European Union. Economia Politica, 36, 205–243.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1947). The creative response in economic history. The Journal of Economic History, 7, 149–159.

Tubadji, A., Nijkamp, P., & Angelis, V. (2016). Cultural hysteresis, entrepreneurship and economic crisis an analysis of buffers to unemployment after economic shocks. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 9, 103–136.

Usai, S. (2011). The geography of inventive activity in OECD regions. Regional Studies, 45, 711–731.

Vezzani, A., Baccan, M., Candu, A., Castelli, A., Dosso, M., & Gkotsis, P. (2017). Smart specialisation, seizing new industrial opportunities. Ispra: Joint Research Centre (Seville site).

Xiao, J., Boschma, R., & Andersson, M. (2018). Resilience in the European Union: The effect of the 2008 crisis on the ability of regions in Europe to develop new industrial specializations. Industrial and Corporate Change, 27, 15–47.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The views expressed are purely those of the authors and may not in any circumstances be regarded as stating an official position of the European Commission.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2: Controlling for spatial correlation

A common feature of regional performance is the presence of spillovers, mostly occurring among neighbour regions.Footnote 3 Spillovers can arise from various factors, such as knowledge flows, inter-regional trade and other linkages among the different regional economic systems. Hence, the performance of a region is likely to be affected by that of neighbour regions. It can also be affected by regions that are further away as for instance through trade, the operations of multinational corporations or international collaborations. The literature has consistently found that the effect of spillover tends to decay with distance, and therefore proximity matters (Jaffe et al. 1993; Iammarino and McCann 2006). Actually, Bottazzi and Peri (2003) suggest that due to the tacit nature of knowledge spillover can be very much localized, according to their estimations, on average, spillover operates on a range of about 300 km.

As a result, we expect that the resilience of a region—hence both SI and RI—isaffected by the resilience of the other regions, with a positive effect that is maximum for continuous regions and decreases with distance.

To identify clusters of high or low resilience we have carried out a Local Indicator of Spatial Association (LISA). LISA allows to assess the similarity of each observation (region) with that of its surroundings. In this way we can identify patterns of spatial clustering for the resilience values.

The LISA identifies the basic regional patterns both for the Sensitivity Index and the Response Index. In Fig. 4, we colour only the values with a significance level of 0.05. It is possible to note that some regions in United Kingdom, Germany and Austria (high resilience) show highly significant local spatial correlations, as well as Greece, Bulgaria and Romania (low resilience).

As Cainelli et al. (2019b) suggest, there are several spatial models available (e.g. SAR model, SEM, Spatial Durbin Model (SDM) etc.). In our paper we want to know whether the dependent variables are related to those of the neighbour clusters, and we assume that the effects of the spatial lag of the dependent variables are linear and constant across observations. This brings us to consider the spatial autoregressive model (SAR), where the outcomes of a region are affected by the outcomes of “nearby” regions.

In order to take into account this feature this section presents spatial autoregressive model (SAR) based on the same model as for the estimates of Tables 1 and 2. The spatial model allows controlling for the effect of similar state in the SI and RI indexes in a given region by neighbours regions through the matrix of contiguity where the centroid of polygons (polygons are the regions) is the reference point (latitude and longitude) to calculate the geographical distance among regions. We have thus generated a matrix of spatial weights based on the distances between points obtaining the lagged dependent variable in space. In the SAR model, y is a function of observable characteristics Xβ, the spatial lags of the dependent variable ρWy and unobservable characteristics ε, producing a spatial regression relationship:

with W that represents the matrix of spatial weights. This model indicates that a region derives an advantage in terms of SI and RI that reflects a linear combination of the resilience (namely RI and SI) of the neighbour regions; B captures the effect of regional characteristics and p represents the effect of the resilience of neighbour regions (conditional on observed regional characteristics).

Tables 6 and 7 report the estimates using the same specification of the results reported in the main text and adding the spatial correlation control for SI and RI respectively. Both estimates report a strong and positive spatial correlation effect, thus confirming the important role played by proximity with other regions to explain the resilience of region i.

To test the robustness of results obtained with the SAR model, we run the estimations also using a spatially auto-correlated error model (SEM). SEM drops the assumption that outcomes are affected by spatial lags of the output variable and instead assume a SAR-type spatial autocorrelation in the error process. The SEM model (Tables 8 and 9), applied to the resilience variables, shows that our results are robust and virtually unchanged.

Turning to our variables of interest, Table 6 shows that patents are still positively correlated with SI, but this is no longer the case for trademarks. Table 7 shows that both patents and trademarks remain strongly and positively correlated with RI. To sum up, the results in this section confirm that more innovative regions are more resilient, particularly when considering technological innovation. Service innovation, most notably KIBS, is not associated to resilience during the crisis, while it is positively associated to resilience in the aftermath of the crisis.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Filippetti, A., Gkotsis, P., Vezzani, A. et al. Are innovative regions more resilient? Evidence from Europe in 2008–2016. Econ Polit 37, 807–832 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-020-00195-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-020-00195-4