Abstract

A cross-national study with university students from Germany (n = 1135) and Turkey (n = 634) tested whether personal belief in a just world (PBJW) predicts students’ life satisfaction and academic cheating. Based on the just-world theory and empirical findings in the school context, we expected university students with a stronger personal BJW to be more satisfied with their lives and cheat less than those with a weaker BJW. Further, we investigated the mediating role of justice experiences with lecturers and fellow students in these relations. Differences in PBJW directly and indirectly predicted undergraduates’ life satisfaction. Students’ justice experiences with peers mediated the relationship between PBJW and life satisfaction. Differences in PBJW indirectly predicted undergraduates’ academic cheating. Students’ justice experiences with lecturers mediated the relationship between PBJW and academic cheating. The results did not differ between German and Turkish students and persisted when we controlled for gender, start of studies, socially desirable responding, general BJW, and self-efficacy. We discussed the importance of personal BJW’s adaptive functions and their relevance for international university research and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Students’ transition from school to university is closely linked with increased self-responsibility, self-regulated learning, and a higher level of expectations (Justus, 2017; Schiefele, Streblow, & Brinkmann, 2007). Due to the change in the learning environment and its new demands on university students, topics such as life satisfaction and cheating behavior in test situations are of interest. Thus, one aim of this research on psychological processes in education is to identify factors that can explain students’ life satisfaction and such unjust behavior. Personal belief in a just world (PBJW) represents an essential factor here. PBJW is focused on a person’s social environment and defined as their conviction that they live in a just world, in which they are usually treated justly (Dalbert, 1999). Researchers have shown that PBJW significantly relates to life satisfaction (e.g., Correia, Batista & Lima, 2009), dishonesty, delinquency, and academic cheating (e.g., Donat, Dalbert, & Kamble, 2014) among secondary school students and adults. Based on the findings, people with a strong PBJW experience a better well-being and behave more justly and socially appropriately than those with weak PBJW.

Because researchers have observed mediating effects of PBJW on well-being and academic cheating in various contexts (e.g., Li, Zhang, & Li, 2017), we also aimed at investigating the role of mediators in our study. The decisive assumption in our study was that these connections would be at least partly mediated by the students’ individual perception of their lecturers’ and fellow students’ just behavior (Anderman, Freeman, & Mueller, 2007). In recent studies, PBJW’s relations to, for example, school-specific well-being (e.g., Donat, Peter, Dalbert, & Kamble, 2016) and several forms of deviant behavior, such as academic cheating (e.g., Donat et al., 2014), have been examined. Investigating university students might further extend our understanding of PBJW’s significance to young people’s psychological functioning. At university, PBJW also seems to play an essential role for experiences in the social environment as well as for behavior in examination situations (Li et al., 2017).

We also focused on the cross-national generalization of the expected relations between PBJW and life satisfaction as well as academic cheating. Some researchers emphasize the cultural dependence (e.g., collectivist vs. individualist) of the effects of PBJW (Laurin, Fitzsimons, & Kay, 2011; Nartova-Bochaver, Donat, Astanina, & Rüprich, 2018; Wu et al., 2011). Therefore, we tested our hypotheses in a German sample first and then used a Turkish sample for a replication.

Belief in a Just World

People’s subjective conviction that they live in a just world and are treated fairly by fellow human beings plays an important role in structuring their life. In theory, this conviction is called ‘belief in a just world’ (BJW). BJW is based on the theory of the justice motive by Lerner (1977). In accordance with his theory, the justice motive serves as a resource in people’s lives and permits an effective interaction with their social environment and life events. Lerner (1977) postulated that people have the need to believe in a just world in which everyone gets what they deserve and deserves what they get. This BJW indicates the justice motive and has been conceptualized as an inter-individually varying disposition (e.g., Dalbert, 2001, Ellard, Harvey & Callan, 2016).

Just-world researchers have identified several adaptive functions of BJW, which have been differentiated by Dalbert (2001) into the assimilation function, the trust function, and the motive function.

The assimilation function serves to preserve BJW by restoring justice cognitively (e.g., by minimizing or denying injustice). It is usually activated by self-experienced or perceived injustice (Dalbert & Donat, 2015) that cannot be eliminated or reduced on the behavioral level (e.g., by compensation). In the school context, for example, students with a stronger BJW felt more justly treated by their teachers and classmates than those with a weaker BJW (Dalbert & Stoeber, 2005; Donat et al., 2014).

The trust function encompasses people’s conviction that they will be treated justly by others (Bègue, 2002) and incorporates the idea that everyone gets what they deserve (Dalbert & Donat, 2015). A frequently investigated, adaptive consequence of the trust function is that BJW helps people maintain their mental health and well-being (e.g., Dalbert, 2001; Hafer & Bègue, 2005).

The motive function includes the obligation of strong just-world believers to act justly and avoid unjust behavior of their own. Empirical evidence shows that students with a strong BJW behaved more equitably toward their schoolmates (Donat, Knigge, & Dalbert, 2018), were more strongly motivated to achieve personal goals by just means, and reported less rule-breaking behavior such as academic cheating or delinquency (e.g., Donat et al., 2014).

Just-world researches have emphasized that it is necessary to distinguish between PBJW and general belief in a just world (GBJW) (e.g., Dalbert, 1999). GBJW represents a person’s conviction that justice prevails all over the world (Dalbert, Montada, & Schmitt, 1987) and is not linked to socially appropriate behavior or a positive view of people’s own life. Researchers have shown that PBJW is more strongly connected with subjective well-being and a better indicator of the justice motive (Dalbert & Donat, 2015; Schindler & Reinhard, 2015). GBJW is a better predictor of harsh social attitudes (see Hafer & Sutton, 2016, for a review) and associated with a lower degree of life satisfaction. Furthermore, Wenzel, Schindler, and Reinhard (2017) identified a positive connection between dishonest behavior and GBJW. Consequently, we focused here on PBJW as the main predictor, but also controlled for effects of GBJW as an additional predictor. This might enable us to identify the predictive role of PBJW in contrast to GBJW.

Personal Belief in a Just World and Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction is defined as a cognitive dimension of subjective well-being indicating how individuals assess their lives and which factors influence their positive judgments regarding their lives (Diener, 1984; Dalbert, 1992). From a theoretical perspective, PBJW serves as a protector of individuals’ well-being (Dalbert, 2001; Hafer & Sutton, 2016) due to its adaptive functions (e.g., assimilation, trust). There is evidence that people’s PBJW relates to their life satisfaction (Dalbert, 1992). Other studies (Lipkus, Dalbert, & Siegler, 1996; Kiral Ucar, Hasta, & Kaynak Malatyali, 2019) showed positive relations between PBJW and life satisfaction among university students from different countries (e.g., USA, Turkey), even when controlling for personality dimensions. Similar results have been identified in experimental studies that confirmed the causal direction of PBJW’s impact on life satisfaction (Correia, Batista et al., 2009, Correia, Kamble, & Dalbert, 2009b).

Personal Belief in a Just World and Academic Cheating

Cheating is described by Pegels (1997) as a small fraud, which leads to a personal advantage in examination situations and can be understood as a form of deviant and unlawful behavior. Marsden, Carroll, and Neill (2005, p. 3) further narrow down academic cheating and define it as “dishonest behavior in a test or exam situation, with possible cheating behaviors including copying from other students, using non-permitted notes, obtaining information about a test from someone who attended an earlier session, and otherwise inappropriately obtaining questions prior to an exam.” This behavior is characterized by a lack of transparency and students’ dishonest and undeserved achievements (Davis, Drinan, & Bertram Gallant, 2009).

The obligation and motivation of strong just-world believers to act justly contradicts immoral and socially deviant behavior (motive function). Thus, cheating not only breaks rules and norms of the university but also those of justice and the personal contract of strong just-world believers to maintain the justice of the world. In line with this reasoning, studies showed the importance of PBJW for appropriate and rule-abiding behavior among Portuguese, Indian, and German secondary school students (Correia, Batista, et al., 2009, Correia, Kamble, et al. 2009b; Donat et al., 2014). Moreover, secondary school students from India and Germany with a strong PBJW were less likely to self-report cheating and delinquent behavior, perpetration of bullying, and school absenteeism than those with a weak PBJW (Donat et al., 2014, Donat, Gallschütz & Dalbert, 2018; Donat, Knigge, et al., 2018). Only a few studies (e.g., Hafer & Rubel, 2015) have considered the relationship between PBJW and academic cheating among university students. To our knowledge, the comparison of German and Turkish students with regard to the effects of PBJW on cheating has not yet been drawn in recent research.

The Mediating Role of Justice Experiences

Although just-world research indicates direct relationships between PBJW and life satisfaction as well as academic cheating, it is plausible that university students’ experiences with justice could mediate these relations. Two groups who could be an important source for justice experiences of university students are lecturers and fellow students (e.g., Dalbert, 2004). Thus, we focused on students’ justice experiences with these groups and defined lecturer justice in accordance with Dalbert and Stoeber’s (2006) definition of teacher justice, that is, as university students’ individually and subjectively experienced justice of their lecturers’ behavior toward them. Similarly, we defined fellow student justice in accordance with Correia and Dalbert’s (2007) study on classmate justice as university students’ individually and subjectively experienced justice of their fellow students’ behavior toward them.

Secondary school students’ PBJW was positively associated with both teacher justice (e.g., Dalbert & Stoeber, 2005; Kiral Ucar & Dalbert, 2018) and classmate justice (e.g., Correia & Dalbert, 2007). In addition, studies have shown that teacher justice (e.g., Dalbert & Stoeber, 2005; Donat, Peter, Dalbert, & Kamble, 2016; Kamble & Dalbert, 2012) and classmate justice (e.g., Correia & Dalbert, 2007) mediated the relation between secondary school students’ PBJW and various indicators of well-being, including life satisfaction.

Accordingly, university students with a strong PBJW could be expected to experience their lecturers’ and fellow students’ behavior toward them as being more just. Just treatment by lecturers and fellow students may further signal that university students are esteemed members of their social group (Group-Value-Theory; Lind & Tyler, 1988), which in turn conveys feelings of belonging and social inclusion (e.g., Umlauft & Dalbert, 2017). These feelings of esteem, belonging, and inclusion may relate positively to students’ life satisfaction.

Furthermore, recent studies have shown that the negative relations between school student’s PBJW and deviant behavior, including cheating (e.g., Donat et al., 2014), were at least partly mediated by justice experiences. The authors argued that just treatment at school motivates students to accept and observe school rules and norms. Secondary school students even generalized this acceptance and observance to institutions outside school, such as the police, the judiciary, and the law in general (e.g., Sanches, Gouveia-Pereira, & Carugati, 2012; Thomas & Mucherah, 2018). Consequently, it would be reasonable to assume that the student’s justice-related learning history also applies to university life. In line with this reasoning, studies showed that the experience of a just treatment in the university environment was significantly associated with reduced levels of academic cheating among university students (e.g., McCabe, Trevino, & Butterfield, 2002; Murdock, Miller, & Goetzinger, 2007). According to McCabe et al. (2002), academic cheating is also dependent on the behavior of fellow students. They argued that the perception of fair behavior and compliance with honor codes by fellow students promotes academic honesty. Therefore, we expected lecturer justice and fellow student justice to mediate the relationship between university students’ PBJW and academic cheating.

Cross-National Differences

Not only cultural differences (religion, political stability, and economic situation) but also university differences (size, selection criteria, and percentage of the population attending university) are of interest when comparing different countries (Gerhards, 2007). In detail, Gerhards (2010) described that Turkish citizens prefer a traditional male-dominated gender order and show an affinity to a more authoritarian regime. Despite these cultural differences, no significant differences of the PBJW have been identified between German and Turkish students (Kiral Ucar & Dalbert, 2018). Differences in PBJW between various countries have often been studied but were not significant (Alves, Gangloff, & Umlauft, 2018; Correia & Dalbert, 2007; Kamble & Dalbert, 2012). Moreover, country-specific factors neither seem to impact the relationship between PBJW and life satisfaction (Correia, Kamble, et al. 2009b; Donat et al., 2016; Kiral Ucar et al., 2019) nor the relationship between PBJW and academic cheating and other delinquent behavior among secondary students (Donat et al., 2014; Donat, Umlauft, Dalbert, & Kamble, 2012). Consequently, we assumed a cross-national generalizability of the adaptive functioning of PBJW. Due to above-mentioned prototypical differences between European countries listed by Gerhards (2007), we tested our hypotheses in a German sample of university students at first and then used a Turkish sample of university students for a replication. Therefore, despite cultural differences in Germany and Turkey, we expect the effects of PBJW on life satisfaction and academic cheating to be similar across both countries.

Present Study

Based on PBJW studies in the school sector, we expected a positive relationship between university students’ PBJW and life satisfaction on the one hand and a negative relationship between their PBJW and academic cheating (e.g., Correia, Batista, et al., 2009, Correia, Kamble, et al. 2009b; Donat et al., 2014) on the other hand. We further examined the mediating role of the students’ justice experiences in PBJW’s associations with life satisfaction and academic cheating (e.g., Donat et al., 2016; Kiral Ucar et al., 2019). We also aimed to test our hypotheses in one country (two German universities) and replicate these findings in another country (two Turkish universities), which would enable us to evaluate the cross-national generalizability of PBJW’s adaptive functioning. The external validity of the study results can also be strengthened by the variance in the structure of the universities where the study was conducted. Everyday university life is comparable at all four universities, although the size of the universities and the classes there differ. Despite the variance, we assume that the adaptive functioning of PBJW does not differ between students.

Our first hypothesis was: The more university students endorse the PBJW, (1a) the more satisfied they are with their lives and (1b) the less academic cheating they self-report.

Our second hypothesis was: Lecturer justice would at least partly mediate the relations between students’ PBJW and their (2a) life satisfaction and (2b) academic cheating.

Our third hypothesis was: Fellow student justice would at least partly mediate the relations between students’ PBJW and their (3a) life satisfaction and (3b) academic cheating.

Control Factors

We expected that the relations described in our hypotheses would remain statistically significant when we controlled for confounding effects of GBJW (as described above), gender, start of studies, academic self-efficacy, and social desirability.Footnote 1

Gender is usually used as a control variable in BJW research (Dalbert & Stoeber, 2006; Donat et al., 2016). Gender differences are also reflected in research on life satisfaction and academic cheating. Girls and women were found to be less satisfied with their lives than boys and men (Bergold, Wirthwein, Rost, & Steinmayr, 2015; Tesch-Römer, Motel-Klingebiel, & Tomasik, 2008). Male students were more likely to cheat than female students at school and university (Anderman & Danner, 2008; Donat et al., 2014; McCabe & Trevino, 1997).

We considered the start of studies as a control factor in the prediction of academic cheating because the duration of studies seems positively related to cheating (Marsden et al., 2005; Patrzek, Sattler, van Veen, Grunschel & Fries, 2015).

According to Bandura (1977), academic self-efficacy describes an individual’s conviction that they can successfully cope with difficult situations and challenges, such as examinations, on their own. Research has revealed a positive relationship between self-efficacy and PBJW (Otto, Glaser, & Dalbert, 2009; Strobel, Tumasjan, & Spörrle, 2011) as well as life satisfaction (Burger & Samuel, 2017; Strobel et al., 2011) and a negative relationship with academic dishonesty (Bolin, 2004; David, 2015; Marsden et al., 2005).

Paulhus (2002) defined socially desirable responding as a person’s tendency to give positive self-descriptions. It would be important to estimate the truthfulness of the self-reported behavior (for a review, see Tourangeau & Yan, 2007) and control for its influence on moral questions (Kemper, Beierlein, Bensch, Kovaleva, & Rammstedt, 2012). Thus, it may be an important factor in predicting students’ academic cheating and life satisfaction because their assessment could be affected by socially desirable responding (Benesch & Raab-Steiner, 2002; Leising, Locke, Kurzius, & Zimmermann, 2016). We used Kemper, Beierlein, Bensch, Kovaleva, and Rammstedt’s approach (2012) in which they differentiate between two facets of social desirability, that is, overstatement of positive qualities (PQ +) and understatement of negative qualities (NQ −).

Method

Participants and Procedure

A total of N = 1769 students from Germany (n = 1135) and Turkey (n = 634) participated in this study. The age range in the overall sample was 18–48 years with an average age of 21.7 years (SD = 3.30). The German/Turkish sample had an age range of 18–48/18–43 years (MGerman = 22.3, SDGerman = 3.63; MTurkish = 20.7, SDTurkisch = 2.31). In total, 27.2% (nGerman = 343; nTurkish = 139) of the students were male and 72.1% (nGerman = 783; nTurkish = 492) female. The start of the participants’ university education varied between 2006 and 2018. More than half of the university students had started their studies in 2016/17. Only 13 of the participants stated that they had begun their studies before 2012.

The survey took place between 2017 and 2018 at two German and two Turkish universities. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Students were invited to take part in a questionnaire-based survey, which took about 20 min, during class time at seminars and lectures. The questionnaire was introduced by a standardized instruction that contained the target intent as well as information about the voluntary and anonymous nature of participation. Demographic data (age, gender, beginning of studies, and course of studies) were assessed at the end.

Measures

Below, the instruments used in our study are presented within the categories of internal personal factors, justice experiences, life satisfaction, and cheating. All instruments were available in German. For the data collection in the Turkish sample, previously adapted and newly translated scales were used. Measures were combined into one questionnaire battery. The participants were instructed to indicate their responses on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 6 (completely agree). For academic cheating, participants rated their responses from 1 (never) to 6 (very often).

Internal Personal Factors

The Personal BJW scale contains 7 items, which capture people’s conviction that they experience justice everywhere in their life (Dalbert, 1999; e.g., “Overall, events in my life are just”; Turkish version adapted by Göregenli, 2003). In the present study, the internal consistency for the German sample was α = .84; rij est = .45Footnote 2 and for the Turkish sample α = .77; rij est = .34 (α varied in other studies between α = .68 and α = .83; Correia, Batista, et al., 2009, Correia, Kamble, et al. 2009b; Donat et al., 2014). Dalbert (1999) has demonstrated the factorial validity of the scale.

The General BJW scale (Dalbert et al., 1987; Schmitt et al., 2008; Turkish version adapted by Göregenli, 2003) contains 6 items describing the belief that justice prevails all over the world (e.g., “I think basically the world is a just place.”). The internal consistency of the scale for the German sample was α = .75; rij est = .32 and for the Turkish sample α = .67; rij est = .25 (α varied in other studies between α = .74 and α = .90; Alves et al., 2018). Dalbert (1999) describes the factorial validity of the scale. Schmitt et al. (2008) carried out a norm-related validation.

We assessed academic self-efficacy using the Academic Self-Efficacy Scale (Jerusalem & Schwarzer, 1981; Turkish version adapted by Yılmaz, Gürçay, & Ekici, 2007) comprising seven items that capture students’ stable expectancy tendency toward their competence in dealing with study-related requirements (German: α = .77; rij est = .32; Turkish: α = .78; rij est = .34; α ranged in other studies between α = .79 and α = .84; Titz, 2001; Yılmaz et al., 2007; e.g., “Even though a test is very difficult, I know that I will succeed”).

We used the Short Scale Social Desirability-Gamma (KSE-G; Kemper et al., 2012; Turkish version adapted by Kiral Ucar, Celik, Baier, Müller & Kals, 2016) to measure people’s tendency to show socially appropriate response behavior. The scale consists of two subscales (overstatement of positive qualities: PQ + , e.g., “In an argument, I always remain objective and stick to the facts.”; understatement of negative qualities: NQ −, e.g., “It has happened that I have taken advantage of someone in the past”, reversely coded) with 3 items each. Reference values for the reliability estimate were ω = .71 for PQ + and ω = .78 for NQ − (Kemper et al., 2012; Kobbé, 2017), which can be interpreted as acceptable. In our study, internal consistencies were: PQ + : αGerman = .49; rij est = .24/αTurkish = .48; rij est = .25; NQ −: αGerman = .43, rij est = .21/αTurkish = .50; rij est = .26). Kemper et al. (2012) introduced the scale as an economic, reliable, and valid measure of the gamma factor of socially desirable response behavior.

Justice Experiences

Lecturer justice was measured using an adapted version of the 10-item Teacher Justice Scale (Dalbert & Stöber, 2002; translated into Turkish for this study), which captures students’ experience of the justice of their lecturers’ behavior toward them personally (German: α = .85; rij est = .35; Turkish: α = .84; rij est = .34; α ranged in other studies between α = .87 and α = .88, Dalbert & Stoeber, 2006; Peter & Dalbert, 2010; e.g., “My lecturers generally treat me justly”). We also measured fellow student justice using an adapted version of the Classmate Justice Scale (Correia & Dalbert, 2007; translated into Turkish for this study) comprising six items (German: α = .84; rij est = .46; Turkish: α = .85; rij est = .48; α ranged in other studies between α = .82 and α = .87, e.g., “My fellow students generally treat me justly”).

Life Satisfaction

Students’ life satisfaction was investigated using the 7-item subscale General Life Satisfaction from Dalbert’s (1992; translated into Turkish for this study) Trait Well-Being Inventory, which captures people’s evaluation of their satisfaction with their past and present life and future perspectives (German: α = .85; rij est = .45; Turkish: α = .87; rij est = .49; α ranged in other studies between α = .86 and α = .90, Dalbert, 1992, 2001; e.g., “I am satisfied with my life”).

Academic Cheating

We assessed self-reported academic cheating using 16 items from McCabe and Treviño’s (1993) Academic Integrity Survey (see also https://honesty.rutgers.edu/rutgersfac.asp for the online version; translated into Turkish for this study), which measures the frequency of university students’ academic dishonesty (German: α = .90; rij est = .36; Turkish: α = .90; rij est = .36; α ranged in other studies between α = .75 and α = .90, Bolin, 2004; McCabe et al., 2002; e.g., “copied from another student during a test or exam”). We further added the timeframe “since the beginning of your study” to the original instrument to increase validity. We formed scale scores by averaging the responses across items, reverse coding negative items as necessary.

Results

Analytical Strategy

Due to the nonparametric data structure, we had to resort to suitable analytical methods. For example, only the comparison of the medians is possible. Other methods like ANOVA are robust for large samples. As a first step, we inspected the correlations between our variables. We also analyzed the correlation patterns regarding differences between the German and the Turkish samples using Box’s M test to assess the homogeneity of the covariance matrices. In addition, based on the nonparametric data, the Mann–Whitney-U-Test was used to test whether the medians of the study variables in the German and Turkish sample significantly differed.

In the next step, separate mediation analyses were calculated for the German and Turkish samples to illustrate a replication of the results. The mediation analyses were performed using the macro named PROCESS v3.3 for IBM SPSS (Hayes, 2017), which is a suitable method for executing a conditional process analysis. If the proposed research model includes mediators, only limited analysis tools are available (Darlington & Hayes, 2017; Hayes & Rockwood, 2020; Montoya & Hayes, 2017). The macro according to Hayes (2017) allows the calculation of various regression models with an integration of mediators and covariates. We chose this statistical strategy because it is robust against violations of the normal distribution and enables the analysis of a nonparametric data structure. For our mediation analyses, we used Model 4 of PROCESS (Hayes, 2017), which allows users to include up to ten parallel operating mediators and a simultaneous control of covariates. We proceeded step by step in the analysis of mediation by including the control variables. In each model, direct and indirect effects are calculated, as well as estimates of bootstrap confidence intervals (CI) for indirect effects. According to Hayes (2017), 5000 bootstrap samples are used to generate the CI. A CI is interpreted as insignificant if it contains zero.

Correlational Results

We first inspected zero-order correlations between all variables (see Table 1). Box’s M test indicated significantly different covariance matrices (F66,3890299.48 = 8.44; p < .001). Thus, Table 1 shows correlations for both countries separately.

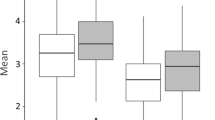

A comparison of the factors between the German and Turkish sample using Mann–Whitney-U test showed that the self-efficacy levels (Mdn(German) = 4.1, Mdn(Turkish) = 4.1; z = − 0.73, p = .47) did not differ. However, the null hypothesis for the variables PBJW (Mdn(German) = 4.5, Mdn(Turkish) = 3.7; z = − 22.10, p = .00), GBJW (Mdn(German) = 3.3, Mdn(Turkish) = 3.7; z = − 6.49, p = .00), lecturer justice (Mdn(German) = 4.4, Mdn(Turkish) = 4.0; z = − 10.16, p = .00), fellow student justice (Mdn(German) = 5, Mdn(Turkish) = 4.5; z = − 13.18, p = .00), life satisfaction (Mdn(German) = 4.9, Mdn(Turkish) = 4.1; z = − 14.56, p = .00), academic cheating (Mdn(German) = 2.1, Mdn(Turkish) = 1.9; z = − 6.41, p = .00) and social desirability (PQ + : Mdn(German) = 4.3, Mdn(Turkish) = 4.7; z = − 9.60, p = .00/NQ −: Mdn(German) = 3.6, Mdn(Turkish) = 4.0; z = − 4.57, p = .00) was not supported. Compared to German university students, Turkish university students reported different levels of the variable. Therefore it is important to check whether PBJW predicts the behavior of both samples in the same way.

Prediction of Life Satisfaction

We then tested the mediation effects of lecturer justice and fellow student justice on the relation between PBJW and life satisfaction. We began by testing these effects in the German sample first (see Table 2) and then in the Turkish sample (see Table 3) by using the same analytic strategy. In Models 1, we tested the mediation without considering control variables which we added in Models 2 (non-psychological variables) and Models 3 (psychological variables).

Model 1 (Table 2) showed significant direct effects of PBJW and fellow student justice on life satisfaction but no direct effect of lecturer justice. Additionally, the direct effect of PBJW was partly mediated by fellow student justice only, as indicated by the significant indirect effect. By considering gender, the explained variance in Model 2 slightly increased and the direct and indirect effects of the predictor and mediators did not change; the effect of gender was insignificant. After adding GBJW, self-efficacy, and both indicators of social desirability in Model 3, the direct and indirect effects of the predictor and mediators changed slightly. The effects of gender (women) and self-efficacy were significant. The explained variance of this model was higher with R2 = 42.82% (F8,952 = 89.11, p < .001). According to Cohen (1988), this represents a large effect size of f2 = .75.

We observed very similar results in the Turkish sample (see Table 3). Model 1 also showed significant direct effects of PBJW and fellow student justice on life satisfaction. The significant direct effect of PBJW was partly mediated by fellow student justice. After adding gender and the psychological control variables in Models 2 and 3, the results changed only slightly. In contrast to the German sample, the direct positive effects of GBJW and understatement of negative qualities were significant. The explained variance in the final model was R2 = 41.32% (F8,582 = 51.23, p < .001). According to Cohen (1988), this represents a large effect size of f2 = .70. The main results of both samples are summarized in Fig. 1.

Final mediation model of the relation between PBJW and life satisfaction considering the control variables. Unstandardized direct effects of the German (above the paths) and the Turkish sample (below the paths) are shown. Indirect effects of PBJW through fellow student justice (bGerman = 0.08, bTurkish = 0.05) were significant. Estimates are based on a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 bootstrap samples (PROCESS for SPSS, Model 4; Hayes, 2018). *p < .05, ***p < .001

Prediction of Academic Cheating

We used the same analytical strategy to test the mediation effects of lecturer justice and fellow student justice on the relation between PBJW and academic cheating. We began by testing these effects in the German sample first (see Table 4) and then in the Turkish sample (see Table 5) by using the same analytic strategy. In Models 1, we tested the mediation without considering control variables which we added in Models 2 (non-psychological variables) and Models 3 (psychological variables).

Model 1 (Table 4) showed a significant direct effect of lecturer justice on academic cheating. Additionally, the direct effect of PBJW was insignificant and mediated by lecturer justice, as indicated by its significant indirect effect. An ANOVA further showed a significant main effect of PBJW on academic cheating in the German sample (F1,28 = 2.04, p < .001).

After adding gender and start of studies, the explained variance in Model 2 slightly increased; the direct and indirect effects of the predictor and mediators did not change. The effects of gender and start of studies were significant. After adding GBJW, self-efficacy, and both indicators of social desirability in Model 3, the significant direct and indirect effects changed slightly. The effects of gender (men), start of studies, GBJW, and both indicators of social desirability were significant. The explained variance of this model was higher with R2 = 20.09% (F9,910 = 25.43, p < .001) According to Cohen (1988), this represents a medium effect size of f2 = .25.

We observed very similar results in the Turkish sample (see Table 5). Again, only lecturer justice was directly related to academic cheating and meditated the direct effect of PBJW in Model 1. An ANOVA further showed a significant main effect of PBJW on cheating in the Turkish sample (F1,32 = 1.48, p < .05). After adding the non-psychological and psychological control variables in Models 2 and 3, the results changed only slightly. The explained variance in the final model was R2 = 22.65% (F9,522 = 16.99, p < .001). According to Cohen (1988), this represents a medium effect size of f2 = .29. In contrast to the German sample, the direct positive effects of GBJW and overstatement of positive qualities were insignificant. Furthermore, Turkish students who started their studies later reported cheating more frequently, whereas this effect was reverse in the German sample. The main results of both samples are summarized in Fig. 2.

Final mediation model of the relation between PBJW and academic cheating considering the control variables. Unstandardized direct effects of the German (above the paths) and the Turkish sample (below the paths) are shown. Indirect effects of PBJW through lecturer justice (bGerman = − 0.158, bTurkish = − 0.06) were significant. Estimates are based on a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 bootstrap samples (PROCESS for SPSS, Model 4; Hayes, 2018). ***p < .001

Discussion

One aim of our study was to investigate the extent to which the expected relations between PBJW and life satisfaction as well as academic cheating and the mediation effects can be generalized across university students from different countries. The results from both studies confirm most of our hypotheses and support other studies that show justice experiences mediate the relationship between PBJW and outcomes in different situational settings (e.g., family, teachers and classmates), and other countries, such as Turkey, India, and Portugal (e.g., Correia & Dalbert, 2007; Dalbert & Stoeber, 2006; Donat et al., 2016; Kamble & Dalbert, 2012; Kiral Ucar et al., 2019).

In line with our first hypothesis, PBJW had a significant positive effect on life satisfaction (Hypothesis 1a). Contrary to our assumptions, the results of the mediation analyses showed no direct negative effect of PBJW on academic cheating. However, two ANOVAs showed a significant main effect of PBJW on academic cheating in both samples. According to Warner (2013), a significant direct effect of X on Y is not a precondition for the mediation analysis. Also, Hayes (2018) disagrees with the idea that the effect of X on Y should only be studied once a non-zero total effect of X on Y has been demonstrated in a bivariate analysis. Thus, our results also support Hypothesis 1b. The more university students believed in a personally just world, the more they were satisfied with their life and the less likely they were to self-report academic cheating. These results are in line with previous studies among secondary school students and adults (e.g., Donat et al., 2014, 2016, Dzuka & Dalbert, 2006) and support the idea that PBJW represents an important resource for people. In our study, it enabled university students to maintain their well-being (life satisfaction) and avoid socially problematic behavior (academic cheating). Due to the adaptive functions of BJW (especially PBJW), students with a strong PBJW seem to be able to cognitively cope with unjust and adverse experiences at university, trust in others, and commit themselves to just behavior toward others. This social obligation is described as a personal contract between people and individuals in their social environment (e.g., Dalbert, 2001). In general, it motivates people to interact justly with their fellow human beings and, in specific, ensures just interaction between lecturers and students. Our study showed that this adaptive functioning seems to apply to university students regarding their life satisfaction and academic cheating from at least two countries, namely Germany and Turkey.

In addition to the effect of PBJW on life satisfaction and academic cheating, an interaction between experiences of justice and PBJW can also be assumed. As discussed above, strong just-world believers perceive others’ behavior as more just, which is reflected in their own experience and behavior and supports the assumption of a mediation effect by justice experiences. Accordingly, in our second and third hypothesis, we expected that students’ justice experiences at the university would at least partly mediate the relations between their PBJW and life satisfaction as well as academic cheating. These justice experiences (1) signal that university students are esteemed members of their social group (Lind & Tyler, 1988), which in turn conveys feelings of belonging and social inclusion (e.g., Umlauft & Dalbert, 2017), and (2) motivate them to accept and observe university rules and norms (e.g., Sanches et al., 2012; Thomas & Mucherah, 2018). These cognitive processes may thus strengthen their well-being and decrease the likelihood that they cheat.

In our study, students’ PBJW was significantly related to lecturer and fellow student justice. Concerning the mediation effects of these justice experiences, we observed differential results for life satisfaction and academic cheating. In both samples, lecturer justice mediated PBJW’s effect on academic cheating and fellow student justice mediated PBJW’s effect on life satisfaction, which partly supported our second and third hypothesis.

It seems that lecturers’ just behavior is more important for establishing just rules and norms which increases students’ motivation to behave accordingly. This could be due to lecturers considering distributional, procedural and interpersonal justice (Peter, Donat, Umlauft, & Dalbert, 2013). McCabe and colleagues (McCabe & Trevino, 1993; McCabe et al., 2002) highlighted the importance of honor codes for the compliant behavior of students at university, especially in exam situations. Lecturers could have a special function here, as they represent the institutionally established guidelines via direct contact with the university students.

However, fellow students’ just behavior seems to be more important for students’ feelings of relatedness, esteem, and inclusion. On the one hand, this is in line with previous studies on secondary school students’ well-being (Correia & Dalbert, 2007; Donat et al., 2016), in which classmate justice but not teacher justice mediated the relation between PBJW and well-being. On the other hand, our result regarding academic cheating is in contrast with, for example, Khodaie, Moghadamzadeh and Salehi (2011) or Marsden et al. (2005) who argue that honest behavior of fellow students in examination situations can serve as a model for a student’s own behavior. Due to the different relevance of the justice experiences for the university-related behavior of the students and their well-being at the university, the findings support the situation-specific impact of the justice experiences which has already been shown in several studies (Dalbert & Stoeber, 2006; Dzuka & Dalbert, 2006; Kamble & Dalbert, 2012).

It is possible that the effect of PBJW on academic cheating among Turkish students may be less pronounced than among German students. An indication of this is provided by comparing the results of the ANOVAs. In this case the cultural differences might be considered as an explanation. As Gerhards (2010) pointed out, the affinity to an authoritarian regime is more strongly marked in the mindset of the Turks. This way of thinking could also be represented by students from Turkey. It is associated with an orientation toward persons with power and the obedience and could have an influence on the student’s perception of the lecturers and their behavior. Thus, a lecturer’s behavior might be more significant for academic cheating than the PBJW. The cultural diversity of German and Turkish students further strengthens the external validity of our results and the possible generalizability of the adaptive functioning of the PBJW.

Control Factors

We expected that the direct and indirect effects of PBJW on life satisfaction and academic cheating would persist when we controlled for the students’ GBJW, gender, start of study, academic self-efficacy, and social desirability. This expectation was supported by our data in both samples.

In detail, we controlled for the effects of GBJW in the prediction of life satisfaction and academic cheating. Due to recent research, we expected that the adaptive functioning of BJW applies more strongly to PJWB than GBJW (for a review, see Hafer & Sutton, 2016). However, researchers emphasize that there might also be cultural differences in the importance of PBJW and GBJW for specific outcomes (e.g., Nortova-Bochaver, Donat, Astanina, & Rüprich, 2018). Indeed, we observed that GBJW was a significant predictor of life satisfaction among Turkish students and academic cheating among German students. Thus, and in accordance with recent research (e.g., Bartholomaeus & Strelan, 2019; Hafer, Busseri, Rubel, Drolet, & Cherrington, 2020), we suggest investing both dimensions of BJW in future studies on university students’ well-being and rule-breaking behavior to rule out their different significance depending on political, cultural, or economic characteristics of countries in this context.

Furthermore, we observed that male students reported being more satisfied with their lives but also cheating more often than females which is in line with recent research (e.g., Anderman & Danner, 2008; Bergold et al. 2015). Interestingly, the effect of start of studies on academic cheating among German (earlier) and Turkish students (later) was reversed, with the effect in the German sample being in line with other studies (e.g., Marsden et al., 2005).

We expected that students with an earlier start of studies would have had more opportunities to cheat due to the duration of their studies and the number of tests they have gone through. The country-specific cultural and political diversity mentioned by Gerhards (2007) in general and for university life in particular could be the reason for the contrasting results. These different circumstances under which German and Turkish students learn could be investigated in future studies.

Our analyses showed that self-efficacy was an important control factor in the explanation of life satisfaction in both samples but was unrelated to academic cheating. In detail, a strong conviction of students to be able to successfully cope with difficult situations and challenges, such as examinations, was associated with high levels of a positive evaluation of their life, which replicates findings from recent studies (e.g., Burger & Samuel, 2017). Furthermore, this conviction might also make it unlikely that university students need to cheat in test situations. However, we did not observe such a relationship in our study which contradicts findings of other research (e.g., David, 2015). This latter result is somewhat surprising because we specifically measured students’ academic self-efficacy. Furthermore, as recent research showed in a Turkish sample of university students (Kiral Ucar et al., 2019), self-efficacy could also function as a mediator in the relation between PBJW and life satisfaction, which could also be investigated in future studies in German students.

We additionally controlled for the effects of students’ tendency to give socially desirable responses. Specifically, we expected overstatement of positive qualities to be positively related to life satisfaction and understatement of negative qualities to be negatively related to academic cheating. In line with the literature (e.g., Tourangeau & Yan, 2007) and our expectation, we observed significant effects of social desirability (esp. understatement of negative qualities) in both samples. Basically, we assume that university students see academic cheating as a rule violation and consequently report it less because of their social desirability. One possible explanation for the missing direct effect of PBJW on self-reported cheating could be that university students who strongly believe in a just world may tend to conceal their dishonest behavior (academic cheating) because it is not compatible with their belief in justice. In contrast, university students who weakly believe in a just world may be more honest about their cheating. From this perspective, we expect a statistically expect a significant positive relation between PBJW and social desirability (Alves & Correia, 2018), especially understatement of negative qualities, but this was not supported by our results. Furthermore, there was only a small effect of understatement of negative qualities on life satisfaction in the Turkish sample. Even these differences found between German and Turkish students could be due to cultural and political attitudes as well as the mentality of the nationality. Thus, future studies, especially those on the relation between PBJW and rule-breaking behavior, should continue controlling for effects of social desirability to avoid biases in the study results.

Altogether, PJWB’s adaptive functioning seems to be similar in German and Turkish students. This finding is in accordance with other international studies (e.g., Correia, Batista, et al., 2009; Correia & Dalbert, 2007; Dzuka & Dalbert, 2006, Kiral Ucar et al., 2019) and supports the idea that PBJW represents a psychological resource across various nations. Although other researchers emphasize the cultural dependence (e.g., collectivistic vs. individualistic) of PBJW’s effects on specific outcomes (Laurin et al., 2011; Nartova-Bochaver et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2011), we did not observe such dependence in the PBJW’s relations to university students’ life satisfaction and academic cheating.

Limitations and Prospects

Some limitations of the study should be noted. The study has a cross-sectional design so that no causal derivations from the results are possible. A longitudinal study would allow a conclusion to be drawn in relation to the causality of the results.

Furthermore, some of the instruments we used were originally developed for application in a German and English context. Therefore, a translation was necessary for the application in Turkey. Despite careful processing, there could have been slight differences in the meaning of items and problems in understanding during investigation. However, we found no differences in the psychometric qualities of our measures between the German and Turkish subsamples. The assessment of social desirability can only be used to a limited extent for interpretation, because the reliability coefficients of the scales were below the acceptable range. A possible explanation would be the small number of times (just two or three) for these scales.

Regarding sample composition, it was a strength of our study that we considered students from two different countries, namely Germany and Turkey. However, the gender distribution was uneven, with 72.1% female and 27.9% male. Thus, our results regarding gender can be generalized to a limited extent only. Our data was collected by self-report measures, which are particularly likely to be distorted when people are asked to disclose sensitive information (e.g., about one’s own cheating). Thus, we considered social desirability as a control factor in our study. We only measured one general, cognitive dimension of university students’ subjective well-being, that is, life satisfaction. It would be interesting to test our hypotheses using a more differentiated approach in relation to BJW and justice experiences in future studies, especially as some authors emphasize in particular the importance of domain-specific effects of PBJW on well-being among secondary school students (e.g., Dalbert & Stoeber, 2006).

We investigated only a few selected mediators and control factors in our study. There might be other constructs that could be important in the explanation of life satisfaction and academic cheating in addition to justice psychological constructs. Thus, researchers should thus consider such constructs as covariates in future studies. Based on evidence from previous studies (Bolin, 2004; Strobel et al., 2011), personality factors, such as self-control or goal orientation could be potential factors for further investigation.

Conclusion

The results of our study replicate most of the existing findings from the school context and can complement research on the transnational significance of PBJW. It represents an important predictor for students’ experience and behavior in the university setting. PBJW may empower students’ general life satisfaction and their honest behavior in exam situations and can thus be interpreted as a psychological resource. Furthermore, PBJW fulfills an essential function in students’ perception of these justice experiences. The conviction of university students that they are treated justly can have a positive effect on their view of life and strengthen the motivation to behave in a socially acceptable manner.

Experiences of justice seem to play a decisive role here. The results show the situation-specific relevance of justice experiences for the university students’ behavior and well-being. Fellow student justice was the important mediator in the relation between PBJW and life satisfaction. In contrast, perceived lecturer justice has been identified as a particularly important mediator in the relation between PBJW and cheating. In the university setting, the significance of students’ experiences of lecturer justice appears to be greater in specific situations, such as test situations, that provide an opportunity to cheat. The consideration of such justice-related aspects by lecturers in everyday university life, such as distributive, procedural, and interpersonal justice (e.g., Peter et al., 2013), might reduce academic dishonesty among students. Students’ experiences of fellow student justice seem to be more important in a more general context, that is, for the students’ life satisfaction. Just fellow student behavior has the potential to provide students with feelings of relatedness, inclusion, and esteem and consequently increases their well-being. Treating others with civility, respect, and dignity might foster these justice experiences (Donat, Rüprich, Gallschütz, & Dalbert, 2020). Thus, researchers should increasingly consider the domain-specific importance of various justice experiences in predicting university students’ behavior and well-being. Simultaneously, they could investigate the functions of BJW and the associated cognitive processes in a more differentiated way.

Notes

In our study, we investigated the Big-Five personality traits as further control factors because we expected significant relations to life satisfaction and academic cheating. We measured them by using the short questionnaire Big-Five-Inventory-10 (BFI-10, Rammstedt & John, 2007), which provides an economic measurement with two items for each trait. In contrast to reports on the inventory’s psychometric attributes, we experienced very low reliabilities and decided to skip the Big-Five from further consideration in this study. Corresponding results can be retrieved from the authors.

Cronbach (1951) showed that alpha depends on the number of items, and introduced rij est as an index of homogeneity, which is independent of test length; for example, as a “rule of thumb,” a test with 16 items with α = .80 has a rij est = .20.

References

Alves, H., & Correia, I. (2018). On the normativity of expressing the belief in a just world: Empirical evidence. Social Justice Research, 21, 106–118.

Alves, H. V., Gangloff, B., & Umlauft, S. (2018). The social value of expressing personal and general belief in a just world in different contexts. Social Justice Research, 31(2), 152–181.

Anderman, E. M., & Danner, F. (2008). Achievement goals and academic cheating. International Review of Social Psychology, 21, 155–180.

Anderman, L. H., Freeman, T. M., & Mueller, C. E. (2007). 9—The “social” side of social context: Interpersonal and affiliative dimensions of students’ experiences and academic dishonesty. In E. M. Anderman & T. B. Murdock (Eds.), Psychology of academic cheating (pp. 203–228). Burlington: Academic Press.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215.

Bartholomaeus, J., & Strelan, P. (2019). The adaptive, approach-oriented correlates of belief in a just world for the self: A review of the research. Personality and Individual Differences, 151, 109485.

Bègue, L. (2002). Beliefs in justice and faith in people: Just world, religiosity, and interpersonal trust. Personality and Individual Differences, 32(3), 375–382.

Benesch, M., & Raab-Steiner, E. (2002). Zur Verfälschbarkeit von Persönlichkeitsfragebogen: Strategien zur Verhinderung und deren Grenzen. Psychologie in Österreich, 22(2–3), 39–41.

Bergold, S., Wirthwein, L., Rost, D. H., & Steinmayr, R. (2015). Are gifted adolescents more satisfied with their lives than their non-gifted peers? Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1623.

Bolin, A. U. (2004). Self-control, perceived opportunity, and attitudes as predictors of academic dishonesty. The Journal of Psychology, 138(2), 101–114.

Burger, K., & Samuel, R. (2017). The role of perceived stress and self-efficacy in young people’s life satisfaction: A longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46, 78–90.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Correia, I., Batista, M. T., & Lima, M. L. (2009a). Does the belief in a just world bring happiness? Causal relationships among belief in a just world, life satisfaction and mood. Australian Journal of Psychology, 61(4), 220–227.

Correia, I., & Dalbert, C. (2007). Belief in a just world, justice concerns, and well-being at Portuguese schools. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 22(4), 421–437.

Correia, I., Kamble, S. V., & Dalbert, C. (2009b). Belief in a just world and well-being of bullies, victims and defenders: A study with Portuguese and Indian students. Anxiety Stress and Coping, 22(5), 497–508.

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334.

Dalbert, C. (1992). Subjektives Wohlbefinden junger Erwachsener: Theoretische und empirische Analysen der Struktur und Stabilität. Zeitschrift für Differentielle und Diagnostische Psychologie, 13, 207–220.

Dalbert, C. (1999). The world is more just for me than generally: About the Personal Belief in a Just World Scale’s validity. Social Justice Research, 12(2), 79–98.

Dalbert, C. (2001). The justice motive as a personal resource: Dealing with challenges and critical life events. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Dalbert, C. (2004). The justice motive in adolescence and young adulthood. London: Routledge.

Dalbert, C., & Donat, M. (2015). Belief in a just world. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (2nd ed., pp. 487–492). Oxford: Elsevier.

Dalbert, C., Montada, L., & Schmitt, M. (1987). Glaube an eine gerechte Welt als Motiv: Validierungskorrelate zweier Skalen. Psychologische Beiträge, 29, 596–615.

Dalbert, C., & Stöber, J. (2002). Gerechtes Schulklima. In J. Stöber (Ed.), Skalendokumentation zum Projekt “Persönliche Ziele von SchülerInnen in Sachsen-Anhalt” (Hallesche Berichte zur Pädagogischen Psychologie Nr. 3) (pp. 34–35). Halle (Saale): Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg, Department of Educational Psychology.

Dalbert, C., & Stoeber, J. (2005). The belief in a just world and distress at school. Social Psychology of Education, 8(2), 123–135.

Dalbert, C., & Stoeber, J. (2006). The personal belief in a just world and domain-specific beliefs about justice at school and in the family: A longitudinal study with adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30(3), 200–207.

Darlington, R. B., & Hayes, A. F. (2017). Regression analysis and linear models: Concepts, applications, and implementation. New York: The Guilford Press.

David, L. T. (2015). Academic cheating in college students: Relations among personal values, self-esteem and mastery. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 187, 88–92.

Davis, S. F., Drinan, P. F., & Bertram Gallant, T. (2009). Cheating in school: What we know and what we con do. Oxford: Whiley.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575.

Donat, M., Dalbert, C., & Kamble, S. V. (2014). Adolescents’ cheating and delinquent behavior from a justice-psychological perspective: The role of teacher justice. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 29(4), 635–651.

Donat, M., Gallschütz, C., & Dalbert, C. (2018a). The relation between students’ justice experiences and their school refusal behavior. Social Psychology of Education, 21, 447–475.

Donat, M., Knigge, M., & Dalbert, C. (2018b). Being a good or a just teacher: Which experiences of teachers’ behavior can be more predictive of school bullying? Aggressive Behavior, 44(1), 29–39.

Donat, M., Peter, F., Dalbert, C., & Kamble, S. V. (2016). The meaning of students’ personal belief in a just world for positive and negative aspects of school-specific well-being. Social Justice Research, 29(1), 73–102.

Donat, M., Rüprich, C., Gallschütz, C., & Dalbert, C. (2020). Unjust behavior in the digital space: The relation between cyber-bullying and justice beliefs and experiences. Social Psychology of Education, 23, 101–123.

Donat, M., Umlauft, S., Dalbert, C., & Kamble, S. V. (2012). Belief in a just world, teacher justice, and bullying behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 38(3), 185–193.

Dzuka, J., & Dalbert, C. (2006). Student violence against teachers: Teachers’ well-being and the belief in a just world. European Psychologist, 12, 253–260.

Ellard, J., Harvey, A., & Callan, M. J. (2016). The justice motive: History, theory, and research. In C. Sabbagh & M. Schmitt (Eds.), Handbook of social justice theory and research (pp. 127–143). New York: Springer.

Gerhards, J. (2007). Cultural overstretch. Differences between Old and New Member States of the EU and Turkey. London: Routledge.

Gerhards, J. (2010). Culture. In S. Immerfall & G. Therborn (Eds.), Handbook of European societies (pp. 157–211). New York: Springer.

Göregenli, M. (2003). Şiddet, kötü muamele ve işkenceye ilişkin değerlendirmeler, tutumlar ve deneyimler. In İşkencenin Önlenmesinde Hukukçuların Rolü Projesi Raporu. İzmir: İzmir Barosu Avrupa Komisyonu.”

Hafer, C. L., & Bègue, L. (2005). Experimental research on just-world theory: Problems, developments, and future challenges. Psychological Bulletin, 131(1), 128–167.

Hafer, C. L., Busseri, M. A., Rubel, A. N., Drolet, C. E., & Cherrington, J. N. (2020). A latent factor approach to belief in a just world and its association with well-being. Social Justice Research, 33, 1–17.

Hafer, C. L., & Rubel, A. N. (2015). The why and how of defending belief in a just world. In J. M. Olson & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 51, pp. 41–96). London: Elsevier.

Hafer, C. L., & Sutton, R. M. (2016). Belief in a just world. In C. Sabbagh & M. Schmitt (Eds.), Handbook of social justice theory and research (pp. 145–160). New York: Springer.

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F., & Rockwood, N. J. (2020). Conditional process analysis: Concepts, computation, and advances in modeling the contingencies of mechanisms. American Behavioral Scientist, 64(1), 19–54.

Jerusalem, M., & Schwarzer, R. (1981). Fragebogen zur Erfassung von „Selbstwirksamkeit“. In R. Schwarzer (Ed.), Skalen zur Befindlichkeit und Persönlichkeit (pp. 15–28). Berlin: Freie Universität, Institut für Psychologie.

Justus, X. (2017). Selbstregulation im virtuellen Studium: Volitionale Regulation, Lernzeit und Lernstrategien in Online-Seminaren. Münster: Waxmann.

Kamble, S. V., & Dalbert, C. (2012). Belief in a just world and wellbeing in Indian schools. International Journal of Psychology, 47(4), 269–278.

Kemper, C. J., Beierlein, C., Bensch, D., Kovaleva, A., & Rammstedt, B. (2012). Eine Kurzskala zur Erfassung des Gamma-Faktors sozial erwünschten Antwortverhaltens: Die Kurzskala Soziale Erwünschtheit-Gamma (KSE-G). Köln: GESIS.

Khodaie, E., Moghadamzadeh, A., & Salehi, K. (2011). Factors affecting the probability of academic cheating school students in Tehran. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 29, 1587–1595.

Kiral Ucar, G., Celik, B., Baier, M., Müller, M., & Kals, E. (2016, July). The ecological belief in a just world and environmental behavior. Poster presented at the XXXI International Congress of Psychology in Yokohama, Japan, July 24–29, 2016. (Abstract published in International Journal of Psychology, 51, 567).

Kiral Ucar, G., & Dalbert, C. (2018). The longitudinal associations between personal belief in a just world and teacher justice among advantaged and disadvantaged school students. International Journal of Psychology, 55(5), 192–200.

Kiral Ucar, G., Hasta, D., & Kaynak Malatyalı, M. (2019). The mediating role of perceived control and hopelessness on the relation between personal belief in a just world and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 143, 68–73.

Kobbé, U. (2017). Die Kurzskala Soziale Erwünschtheit-Gamma (KSE-G). In U. Kobbé (Ed.), Forensische Prognosen. Ein transdisziplinäres Praxismanual. Standards, Leitfäden, Kritik (pp. 245–248). Lengerich: Pabst.

Laurin, K., Fitzsimons, G. M., & Kay, A. C. (2011). Social disadvantage and the self-regulatory function of justice beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 149–171.

Leising, D., Locke, K. D., Kurzius, E., & Zimmermann, J. (2016). Quantifying the association of self-enhancement bias with self-ratings of personality and life satisfaction. Assessment, 23(5), 588–602.

Lerner, M. J. (1977). The justice motive: Some hypotheses as to its origins and forms. Journal of Personality, 45(1), 1–52.

Li, S.-S., Zhang, Y.-C., & Li, X.-P. (2017). Belief in a just world on psychological well-being among college students: The effect of trait empathy and altruistic behavior. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 25(2), 359–362.

Lind, E. A., & Tyler, T. R. (1988). The social psychology of procedural justice. New York: Plenum.

Lipkus, I. M., Dalbert, C., & Siegler, I. C. (1996). The importance of distinguishing the belief in a just world for self versus for others: Implications for psychological well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(7), 666–677.

Marsden, H., Carroll, M., & Neill, J. T. (2005). Who cheats at university? A self-report study of dishonest academic behaviours in a sample of Australian university students. Australian Journal of Psychology, 57(1), 1–10.

McCabe, D. L., & Trevino, L. K. (1993). Academic dishonesty: Honor codes and other contextual influences. The Journal of Higher Education, 64(5), 522–538.

McCabe, D. L., & Trevino, L. K. (1997). Individual and contextual influences on academic dishonesty: A multicampus investigation. Research in Higher Education, 38(3), 379–396.

McCabe, D. L., Trevino, L. K., & Butterfield, K. D. (2002). Honor codes and other contextual influences on academic integrity: A replication an extension to modifies honor code settings. Research in Higher Education, 43(3), 357–378.

Montoya, A. K., & Hayes, A. F. (2017). Two-condition within-participant statistical mediation analysis: A path-analytic framework. Psychological Methods, 22, 6–27.

Murdock, T. B., Miller, A. D., & Goetzinger, A. (2007). Effects of classroom context on university students’ judgments about cheating: Mediating and moderating processes. Social Psychology of Education, 10(2), 141–169.

Nartova-Bochaver, S., Donat, M., Astanina, N., & Rüprich, C. (2018). Russian adaptations of General and Personal Belief in a Just World Scales: Validation and psychometric properties. Social Justice Research, 31, 61–84.

Otto, K., Glaser, D., & Dalbert, C. (2009). Mental health, occupational trust, and quality of working life: Does belief in a just world matter? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39(6), 1288–1315.

Patrzek, J., Sattler, S., van Veen, F., Grunschel, C., & Fries, S. (2015). Investigating the effect of academic procrastination on the frequency and variety of academic misconduct: A panel study. Studies in Higher Education, 40(6), 1014–1029.

Paulhus, D. L. (2002). Socially desirable responding: The evolution of a construct. In H. I. Braun, D. N. Jackson, D. E. Wiley, & S. Messick (Eds.), The role of constructs in psychological and educational measurement (pp. 67–88). Mahwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum.

Pegels, E. M. (1997). Mogeln und Moral: empirische und theoretische Studien über den Wert des Mogelns in der Schule. Münster: Lit.

Peter, F., & Dalbert, C. (2010). Do my teachers treat me justly? Implications of students’ justice experience for class climate experience. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 35(4), 297–305.

Peter, F., Donat, M., Umlauft, S., & Dalbert, C. (2013b). Einführung in die Gerechtigkeitspsychologie. In C. Dalbert (Ed.), Gerechtigkeit in der Schule (pp. 11–32). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Rammstedt, B., & John, O. P. (2007). Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), 203–212.

Sanches, C., Gouveia-Pereira, M., & Carugati, F. (2012). Justice judgements, school failure, and adolescent deviant behaviour. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(4), 606–621.

Schiefele, U., Streblow, L., & Brinkmann, J. (2007). Aussteigen oder Durchhalten. Was unterscheidet Studienabbrecher von anderen Studierenden? Zeitschrift für Entwicklungspsychologie und Pädagogische Psychologie, 39(3), 127–140.

Schindler, S., & Reinhard, M.-A. (2015). Catching the liar as a matter of justice: Effects of belief in a just world on deception detection accuracy and the moderating role of mortality salience. Personality and Individual Differences, 73, 105–109.

Schmitt, M., Dalbert, C., Montada, L., Gschwendner, T., Maes, J., Reichle, B., et al. (2008). Verteilung des Glaubens an eine gerechte Welt in der Allgemeinbevölkerung. Normwerte für die Skala Allgemeiner Gerechte-Welt-Glaube. Diagnostica, 54(3), 150–163.

Strobel, M., Tumasjan, A., & Spörrle, M. (2011). Be yourself, believe in yourself, and be happy: Self-efficacy as a mediator between personality factors and subjective well-being. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 52(1), 43–48.

Tesch-Römer, C., Motel-Klingebiel, A., & Tomasik, M. J. (2008). Gender differences in subjective well-being: Comparing societies with respect to gender equality. Social Indicators Research, 85(2), 329–349.

Thomas, K. J., & Mucherah, W. M. (2018). Brazilian adolescents’ just world beliefs and its relationships with school fairness, student conduct, and legal authorities. Social Justice Research, 31(1), 41–60.

Titz, W. (2001). Emotionen von Studierenden in Lernsituationen: Explorative Analysen und Entwicklung von Selbstberichtskalen. München: Waxmann.

Tourangeau, R., & Yan, T. (2007). Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychological Bulletin, 133(5), 859–883.

Umlauft, S., & Dalbert, C. (2017). Justice experiences and feelings of exclusion. Social Psychology of Education, 20(3), 565–587.

Warner, R. M. (2013). Applied statistics: From bivariate through multivariate techniques (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Wenzel, K., Schindler, S., & Reinhard, M.-A. (2017). General belief in a just world is positively associated with dishonest behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1770.

Wu, M. S., Yan, X., Zhou, C., Chen, Y., Li, J., Zhu, Z., et al. (2011). General belief in a just world and resilience: Evidence from a collectivistic culture. European Journal of Personality, 25, 431–442.

Yılmaz, M., Gürçay, D., & Ekici, G. (2007). Adaptation of the academic self-efficacy scale to Turkish. Hacettepe University The Journal of Education, 33, 253–259.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Kerem Aslan for his translation of the German items into Turkish and Serhat Yalçın for his back-translation from Turkish into German. We would also like to thank Gamze Özdemir for helping us to collect the data.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Münscher, S., Donat, M. & Kiral Ucar, G. Students’ Personal Belief in a Just World, Well-Being, and Academic Cheating: A Cross-National Study. Soc Just Res 33, 428–453 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-020-00356-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-020-00356-7