Abstract

Affective states are closely linked to attention to internal aspects of the self (i.e., self-focused attention). We investigated how self-focused attention induced by emotional experiences affects memory for subsequently presented information. Prior to incidental encoding of affectively neutral target words, participants were induced to feel shame or anger through autobiographical recall (vs. no emotion-induction control condition). Memory for words (item memory) and their associated contextual features (source memory) were subsequently assessed. Self-focused attention, measured by the private self-consciousness scale, was highest in the shame condition, followed by the anger and then control conditions. Item memory was significantly impaired in the shame condition compared to both the anger and control conditions, and self-focused attention negatively mediated the effect of emotion condition on memory performance. Source memory did not significantly differ across the emotion conditions, and we discuss possible factors contributing to this null finding. Our findings suggest that emotion-induced self-focused attention may reduce attentional resources available for encoding task-relevant external information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

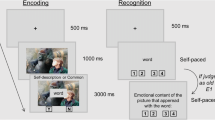

Source memory can be assessed in conjunction with item memory whereby participants are first asked to determine whether or not a given item had been previously presented in the encoding phase, and then, only for the items that were determined as having been presented, to further indicate their associated source feature (e.g., Doerksen and Shimamura 2001). Alternatively, source memory can be assessed independently of item memory by having participants indicate the source feature of all studied items, for example using a forced-choice test (e.g., Davidson et al. 2006). In the present study, we opted to use an independent test of source memory that is not contingent on correct item recognition.

We asked participants to complete these questionnaires at the end of the experiment in an attempt to reduce the likelihood that they would be aware of the fact that their mood and the resulting self-focused attention were being manipulated or the purpose/hypothesis of the study.

A parallel set of analyses using d-prime (d′) as the dependent measure produced exactly the same pattern of results. Complete statistical analyses and results are presented in Appendix 2.

The same null results were obtained when source memory accuracy was conditionalised on correct item recognition (i.e., the proportion of correctly recognised old items that were attributed to their correct source, P(source correct | hit)). Complete statistical analyses and results are presented in Appendix 3.

References

Agatstein, F. C., & Buchanan, D. B. (1984). Public and private self-consciousness and the recall of self-relevant information. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 10, 314–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167284102019.

Allen, R. J., Schaefer, A., & Falcon, T. (2014). Recollecting positive and negative autobiographical memories disrupts working memory. Acta Psychologica, 151, 237–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2014.07.003.

Bargh, J. A. (1982). Atttention and automaticity in the processing of self-relevant information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 425–436. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.43.3.425.

Baddeley, A. D., Lewis, V., Eldridge, M., & Thomson, N. (1984). Attention and retrieval from long-term memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 13, 518–540. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.113.4.518.

Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (1999). Affective Norms for English Words (ANEW): Instruction manual and affective ratings (Technical Report C-1). Gainesville, FL: The Center for Research in Psychophysiology, University of Florida. Retrieved from https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.306.3881

Carver, C. S. (1979). A cybernetic model of self-attention processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 1251–1280. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.37.8.1251.

Carver, C. S., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2009). Anger is an approach-related affect: Evidence and implications. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 183–204. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013965.

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1981). Attention and self-regulation: A control theory approach to human behavior. New York: Springer.

Craik, F. I. M., Govoni, R., Naveh-Benjamin, M., & Anderson, N. D. (1996). The effects of divided attention on encoding and retrieval processes in human memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 125, 159–180. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.125.2.159.

Cortheart, M. (1981). The MRC psycholinguistic database. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 33A, 497–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/14640748108400805.

Curci, A., Lanciano, T., Soleti, E., & Rimé, B. (2013). Negative emotional experiences arouse rumination and affect working memory capacity. Emotion, 13, 867–880. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032492.

Davidson, P. S. R., McFarland, C. P., & Glisky, E. L. (2006). Effects of emotion on item and source memory in young and old adults. Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Neuroscience, 6, 306–322. https://doi.org/10.3758/CABN.6.4.306.

Doerksen, S., & Shimamura, A. P. (2001). Source memory enhancement for emotional words. Emotion, 1, 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.1.1.5.

Duval, S., Duval, V. H., & Mulilis, J. P. (1992). Effects of self-focus, discrepancy between self and standard, and outcome expectancy favorability on the tendency to match self to standard or to withdraw. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 340–348. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.62.2.340.

Duval, S., & Wicklund, R. A. (1972). A theory of objective self-awareness. New York: Academic Press.

Duval, S., & Wicklund, R. A. (1973). Effects of objective self-awareness on attribution of causality. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 9, 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(73)90059-0.

Eichstaedt, J., & Silvia, P. J. (2003). Noticing the self: Implicit assessment of self-focused attention using word recognition latencies. Social Cognition, 21, 349–361. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.21.5.349.28686.

Ellis, H. C., Thomas, R. L., McFarland, A. D., & Lane, J. W. (1985). Emotional mood states and retrieval in episodic memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 11, 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.11.2.363.

Ellis, H. C., Thomas, R. L., & Rodriguez, I. A. (1984). Emotional mood states and memory: Elaborative encoding, semantic processing, and cognitive effort. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 10, 470–482. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.10.3.470.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioural, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146.

Fenigstein, A. (1984). Self-consciousness and the overperception of self as a target. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 860–870. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.47.4.860.

Fenigstein, A., Scheier, M. F., & Buss, A. H. (1975). Public and private self-consciousness: Assessment and theory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43, 522–527. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076760.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Branigan, C. (2005). Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cognition and Emotion, 19, 313–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930441000238.

Frijda, N. H., Ortony, A., Sonnemans, J., & Clore, G. L. (1992). The complexity of intensity: Issues concerning the structure of emotion intensity. In M. Clark (Ed.), Emotion: Review of personality and social psychology (Vol. 13, pp. 60–89). Newbury Park: Sage.

Gable, P., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2010). The motivational dimensional model of affect: Implications for breadth of attention, memory, and cognitive categorization. Cognition and Emotion, 24, 322–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930903378305.

Gray, J. (2001). Emotional modulation of cognitive control: Approach-withdrawal states double-dissociate spatial from verbal two-back task performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 130, 436–452. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.130.3.436.

Green, J. D., & Sedikides, C. (1999). Affect and self-focused attention revisited: The role of affect orientation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 104–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167299025001009.

Green, J. D., Sedikides, C., Saltzberg, J. A., Wood, J. V., & Forzano, L. A. B. (2003). Happy mood decreases self-focused attention. British Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466603763276171.

Hamilton, V. (1975). Socialization anxiety and information processing: A capacity model of anxiety-induced performance deficits. In I. G. Sarason & C. D. Spielberger (Eds.), Stress and anxiety (Vol. 2, pp. 45–68). New York: Wiley.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford.

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76, 408–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750903310360.

Herrald, M. M., & Tomaka, J. (2002). Patterns of emotion-specific appraisal, coping, and cardiovascular reactivity during an ongoing emotional episode. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8, 434–450. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.83.2.434.

Hertel, P. T., Benbow, A. A., & Geraerts, E. (2012). Brooding deficits in memory: Focusing attention improves subsequent recall. Cognitive and Emotion, 26, 1516–1525. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2012.668852.

Hertel, P. T., & Rude, S. S. (1991). Depressive deficits in memory: Focusing attention improves subsequent recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 120, 301–309. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.120.3.301.

Hull, J. G., & Levy, A. S. (1979). The organizational functions of the self: An alternative to the Duval and Wicklund model of self-awareness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 756–768. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.37.5.756.

Hull, J. G., Slone, L. B., Meteyer, K. B., & Matthews, A. R. (2002). The nonconsciousness of self-consciousness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 406–424. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.83.2.406.

Hull, J. G., Van Treuren, R. R., Ashford, S. J., Propsom, P., & Andrus, B. W. (1988). Self-consciousness and the processing of self-relevant information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 452–465. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.3.452.

Ingram, R. E. (1990). Self-focused attention in clinical disorders: Review and a conceptual model. Psychological Bulletin, 109, 156–176. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.156.

Isen, A. M., & Gorgoglione, J. M. (1983). Some specific effects of four affect-induction procedures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 9, 136–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167283091019.

Johnson, M. K., Foley, M. A., Suengas, A. G., & Raye, C. L. (1988). Phenomenal characteristics of memory for perceived and imagined autobiographical events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 117, 371–376. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.117.4.371.

Johnson, M. K., Hashtroudi, S., & Lindsay, D. S. (1993). Source monitoring. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.3.

Kahneman, D. (1973). Attention and effort. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Keltner, D., Ellsworth, P. C., & Edwards, K. (1993). Beyond simple pessimism: Effects of sadness and anger on social perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 740–752. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.64.5.740.

Kesebir, S., & Oishi, S. (2010). A spontaneous self-reference effect in memory: Why some birthdays are harder to remember than others. Psychological Science, 21, 1525–1531. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610383436.

Kimble, C. E., Hirt, E. R., & Arnold, E. M. (1985). Self-consciousness, public and private self-awareness, and memory in a social setting. The Journal of Psychology, 119, 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1985.9712607.

Kimble, C. E., & Zehr, H. D. (1982). Self-consciousness, information load, self-presentation, and memory in a social situation. The Journal of Social Psychology, 118, 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1982.9924416.

Lazarus, R. S. (1993). From psychological stress to the emotions: A history of changing outlooks. Annual Review of Psychology, 44, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.44.020193.000245.

Mirandola, C., & Toffalini, E. (2016). Arousal—but not valence—reduces false memories at retrieval. PLoS ONE, 11, e0148716. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0148716.

Mor, N., & Winquist, J. (2002). Self-focused attention and negative affect: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 638–662. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.128.4.638.

Nasby, W. (1985). Private self-consciousness, articulation of the self-schema, and recognition memory of trait adjectives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 704–709. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.49.3.704.

Naveh-Benjamin, M., Craik, F. I. M., Perretta, J. G., & Tonev, S. T. (2000). The effects of divided attention on encoding and retrieval processes: The resiliency of retrieval processes. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 53A, 609–625. https://doi.org/10.1080/713755914.

Nielson, K. A., & Bryant, T. (2005). The effects of noncontingent extrinsic and intrinsic rewards on memory consolidation. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 84, 42–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2005.03.004.

Nielson, K. A., & Powless, M. (2007). Positive and negative sources of emotional arousal enhance long-term word-list retention when induced as long as thirty minutes after learning. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 88, 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2007.03.005.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 400–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x.

Panayiotou, G., Brown, R., & Vrana, S. R. (2007). Emotional dimensions as determinants of self-focused attention. Cognition and Emotion, 21, 982–998. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930701319170.

Panayiotou, G., & Vrana, S. R. (1998). Effect of self-focused attention on the startle reflex, heart rate, and memory performance among socially anxious and nonanxious individuals. Psychophysiology, 35, 328–336. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0048577298960875.

Rogers, T. B., Kuiper, N. A., & Kirker, W. S. (1977). Self-reference and the encoding of personal information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35, 677–688. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.35.9.677.

Roskes, M., Elliot, A. J., Nijstad, B. A., & De Dreu, C. K. (2013). Avoidance motivation and conservation of energy. Emotion Review, 5, 264–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073913477512.

Salovey, P. (1992). Mood-induced self-focused attention. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 699–707. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.62.4.699.

Sedikides, C. (1992). Mood as a determinant of attentional focus. Cognition and Emotion, 6, 129–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699939208411063.

Schaefer, A., & Phillippot, P. (2005). Selective effects of emotion on the phenomenal characteristics of autobiographical memories. Memory, 13, 148–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210344000648.

Scheier, M. F., Buss, A. H., & Buss, D. M. (1978). Self-consciousness, self-report of aggressiveness, and aggression. Journal of Research in Personality, 12, 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-6566(78)90089-2.

Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. (1977). Self-focused attention and the experience of emotion: Attraction, repulsion, elation, and depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35, 625–636. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.35.9.625.

Scherer, K. R., & Wallbott, H. G. (1994). Evidence for universality and cultural variation of differential emotion response patterning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 310–328. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.66.2.310.

Serbun, S. J., Shih, J. Y., & Gutchess, A. H. (2011). Memory for details with self-referencing. Memory, 19, 1004–1014. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2011.626429.

Storbeck, J., & Clore, G. L. (2005). With sadness comes accuracy; with happiness, false memory: Mood and the false memory effect. Psychological Science, 16, 785–791. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01615.x.

Storbeck, J., & Clore, G. L. (2011). Affect influences false memories at encoding: Evidence from recognition data. Emotion, 11, 981–989. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022754.

Suengas, A. G., & Johnson, M. K. (1988). Qualitative effects of rehearsal on memories for perceived and imagined complex events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 117, 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.117.4.377.

Silvia, P. J., Kelly, C. S., Zibaie, A., Nardello, J. L., & Moore, L. C. (2013). Trait self-focused attention increases sensitivity to nonconscious primes: Evidence from effort-related cardiovascular reactivity. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 88, 143–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.03.007.

Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. L. (2002). Shame and guilt. New York: Guilford.

Tangney, J. P., Miller, R. S., Flicker, L., & Barlow, D. H. (1996). Are shame, guilt, and embarrassment distinct emotions? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 1256–1269. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.6.1256.

Threadgill, A. H., & Gable, P. (2019). Negative affect varying in motivational intensity influences scope of memory. Cognition and Emotion, 33, 332–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2018.1451306.

Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2007). The self in self-conscious emotions: A cognitive appraisal approach. In J. L. Tracy, R. W. Robins, & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research (pp. 3–20). New York: Guilford.

Troyer, A. K., Winocur, G., Craik, F. I. M., & Moscovitch, M. (1999). Source memory and divided attention: Reciprocal costs to primary and secondary tasks. Neuropsychology, 13, 467–474. https://doi.org/10.1037/0894-4105.13.4.467.

Vallacher, R. R. (1978). Objective self-awareness and the perception of others. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 4, 63–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/014616727800400113.

Van Damme, I. (2013). Mood and the DRM paradigm: An investigation of the effects of valence and arousal on false memory. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 66, 1060–1081. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2012.727837.

Wang, B. (2015). Negative emotion elicited in high school students enhances consolidation of item memory, but not source memory. Consciousness and Cognition, 33, 185–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2014.12.015.

Wang, B., & Sun, B. (2015). Timing matters: Negative emotion elicited 5 min but not 30 min or 45 min after leaning enhances consolidation of internal-monitoring source memory. Acta Psychologica, 157, 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2015.02.006.

Watkins, E., & Brown, R. G. (2002). Rumination and executive function in depression: An experimental study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 72, 400–402. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.72.3.400.

Wells, G. L., Hoffman, C., & Enzle, M. E. (1984). Self- versus other-referent processing at encoding and retrieval. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 10, 574–584. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167284104010.

Wood, J. V., Saltzberg, J. A., & Goldsamt, L. A. (1990). Does affect induce self-focused attention? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 899–908. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.5.899.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Grant in Support of Scholarship (GISOS) from Wesleyan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

The structure of the MCQ composite variables, Cronbach’s Alphas, and corresponding items.

Composite variable | Cronbach’s α | Items |

|---|---|---|

Clarity | .835 | My memory for the event was dim vs. sharp/clear. My memory for the event involved visual details. My memory for the event was sketchy vs. very detailed. The order of events in my memory was confusing vs. comprehensible. Overall, my memory for the event was vague vs. very vivid. Overall, I remembered the event hardly vs. very well. |

Sensory | .605 | My memory for the event involved sound. My memory for the event involved smell. My memory for the event involved taste. My memory for the event involved touch. |

Contextual | .630 | My memory for the location where the event took place was vague vs. clear/distinct. In my memory, relative spatial arrangement of objects was vague vs. clear/distinct. In my memory, relative spatial arrangement of people was vague vs. clear/distinct. |

Time | .729 | My memory for the time when the event took place was vague vs. clear/distinct. My memory for the year when the event took place was vague vs. clear/distinct. My memory for the season when the event took place was vague vs. clear/distinct. My memory for the day when the event took place was vague vs. clear/distinct. My memory for the hour when the event took place was vague vs. clear/distinct. |

Thoughts and feelings | .645 | I remembered what I thought at the time when the event took place: Not at all vs. clearly. I remembered how I felt at the time when the event took place: not at all vs. clearly. |

Valence of feelingsa | My feelings at the time when the event took place were negative vs. positive. | |

Intensity of feelingsa | My feelings at the time when the event took place were not intense vs. very intense. |

Appendix 2

Statistical results of item memory using d-prime as a measure of performance

The proportion of missing responses (Shame: M = .004, SD = .007; Anger: M = .004, SD = .009; Control: M = .004, SD = .007) did not significantly differ across the emotion conditions, F(2, 237) = 0.122, p = .885. Missing responses were counted as incorrect responses. For each participant, d-prime score was calculated by subtracting z-score-transformed false-alarm rates (the proportion of “new” words incorrectly identified as old) from z-score-transformed hit rates (i.e., the proportion of “old” words correctly recognised as old). One-sample t-tests showed that d-prime scores were significantly above chance performance level of zero across all Emotion conditions, all t(79)s > 15.472, all ps < .05. A one-way ANOVA conducted on d-prime scores with Emotion (shame, anger, control) as the between-subjects factor revealed a significant effect of Emotion, F(2, 237) = 5.317, p = .006, ηp2 = .043. Bonferroni-corrected post-hoc tests revealed that item memory was significantly impaired in the Shame condition (M = 0.770, SD = 0.445) compared to both the Anger (M = 0.973, SD = 0.372), p = .010, and Control conditions (M = 0.950, SD = 0.472), p = .026. Item memory did not significantly differ between the Anger and Control conditions, p = .999.

To examine whether self-focused attention mediated the effect of Emotion condition on item memory performance, we ran two mediation analyses with PROCESS macro for SPSS (model 4; Hayes 2018) using bootstrapping procedures with 10,000 samples. In the first analysis, we dummy-coded the Emotion condition to examine the relative direct effect, indirect effect, and total effect (i.e., the sum of the direct and indirect effects) of the Shame condition and Anger condition, respectively, relative to the Control condition (i.e., reference group). In the second analysis, we used two orthogonal contrasts to examine relative direct, indirect, and total effects of (a) Shame and Anger conditions collectively (i.e., Emotions) relative to the Control condition (contrast coded as Shame = 1/3, Anger = 1/3, Control = – 2/3) and (b) the Shame condition relative to the Anger condition (contrast coded as Shame = 1/2, Anger = – 1/2, Control = 0), respectively.

As shown in Table 5, relative to the Control condition, the Shame condition had a significant negative indirect effect on item memory accuracy via self-focused attention as well as a significant negative total effect, but a nonsignificant direct effect. Relative to the Control condition, the Anger condition had a significant negative indirect effect on item memory via self-focused attention but a nonsignificant total effect, suggesting that the nonsignificant yet positive direct effect counteracted the negative indirect effect. Relative to the Control condition, the two emotion conditions (Shame and Anger) collectively had a significant negative indirect effect on item memory accuracy via self-focused attention, but nonsignificant direct and total effects. Relative to the Anger condition, the Shame condition had a significant indirect effect on item memory accuracy via self-focused attention as well as significant direct and total effects, all of which were in a negative direction.

Appendix 3

Statistical results of source memory accuracy conditionalised on correct item recognition

Source memory accuracy was calculated as the proportion of correctly recognized old words that were attributed to the correct source, P(source correct | hit). The overall proportion of missing responses (Shame: M = .004, SD = .009; Anger: M = .005, SD = .010; Control: M = .004, SD = .009) did not significantly differ across the emotion conditions, F(2, 237) = 0.246, p = .782. Missing responses were counted as incorrect responses, conditionalised on correct item recognition. One-sample t-tests showed that source memory accuracy was significantly above chance performance level of .50 across all Emotion conditions, all t(79)s > 2.884, all ps < .05. A one-way ANOVA with Emotion (shame, anger, control) as the between-subjects factor revealed no significant effect of Emotion, F(2, 237) = 0.132, p = .877 (Shame: M = .533, SD = .093; Anger: M = .531, SD = .097; Control: M = .539, SD = .104)

To examine whether self-focused attention mediated the effect of Emotion condition on source memory performance, we ran two mediation analyses using PROCESS macro for SPSS (model 4; Hayes 2018) using bootstrapping procedures with 10,000 samples. In the first analysis, we dummy-coded the Emotion condition to examine the relative direct effect, indirect effect, and total effect (i.e., the sum of the direct and indirect effects) of the Shame condition and Anger condition, respectively, relative to the Control condition (i.e., reference group). In the second analysis, we used orthogonal contrasts to examine relative direct, indirect, and total effects of (a) Shame and Anger conditions collectively (i.e., Emotions) relative to the Control condition (contrast coded as Shame = 1/3, Anger = 1/3, Control = – 2/3) and (b) the Shame condition relative to the Anger condition (contrast coded as Shame = 1/2, Anger = – 1/2, Control = 0), respectively. As shown in Table 6, the results of these analyses revealed that none of the direct, indirect, or total effects was statistically significant.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jeon, Y.A., Resnik, S.N., Feder, G.I. et al. Effects of emotion-induced self-focused attention on item and source memory. Motiv Emot 44, 719–737 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-020-09830-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-020-09830-w