Abstract

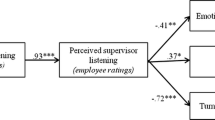

Emotions are a ubiquitous part of the workplace, and research on emotion sharing suggests that people often seek out others to express and share their emotions, in particular their negative emotions. Drawing from theory on sensemaking within organizations, we argue that employee perceptions of listener responses to negative emotion/stressful-event sharing have a significant impact on how included employees feel with their peers and their organization-based self-esteem. If employees perceive that others have responded positively to their sharing of negative emotions, they will experience positive inclusion and esteem beliefs and seek to maintain these positive views through socially attached attitudes (i.e., greater commitment and lower turnover intentions). However, if employees perceive listeners have responded negatively, inclusion, esteem, and socially attached attitudes will suffer. Across two studies, we found that employees’ perceptions that others tended to respond to them in a positive manner (e.g., by being supportive and validating the employees’ perspective) predicted the extent to which employees felt included, and experienced positive organization-based self-esteem. In turn, this translated into increased organizational commitment and decreased turnover intentions. In contrast, perceived negative listener reactions (e.g., responding in a critical or disengaged manner) threatened these outcomes. Our second study suggested that these effects are more driven by identity (i.e., esteem)-related processes than by generalized perceptions of social support, and that these effects are stronger for those with lower levels of communion striving.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A final distinction involves measurement. As we define listener reactions as perceived interpersonal cues, we take a behavioral approach towards listener reactions in both our theory and measurement by asking employees to reflect on specific behaviors that coworkers did or did not enact. In contrast, as Mathieu et al. (2018) recently pointed out, the social support literature has tended to focus on general evaluations of support to the neglect of studying what individuals perceive that others say and do in social support situations. Thus, our conceptualization of positive listener reactions is more context-specific, deliberate in its behavioral approach to measurement, and closely aligned with emotion sharing theory and includes a greater variety of social reactions (i.e., incorporation of negative listener reactions) than received social support.

Wrzesniewski et al. (2003) did not quantitatively measure interpersonal cues but instead took a qualitative, story-telling approach. Fenalson and Beehr (1994) introduced a communication measure reflecting positive interactions in the workplace, but their measure assesses general conversations that occur (e.g., “we talk about the good things about our work”), and not specific reactions others may express when one shares a negative emotion/experience. Recent meta-analytic evidence suggests that there does not appear to be a consistently used/agreed-upon measure of received social support in the literature (Mathieu et al., 2018). Finally, a thorough search of the literature did not reveal a suitable measure of negative reactions within a work context.

References

Allen, N., & Meyer, J. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63, 1–18.

Ashforth, B., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39.

Barrick, M. R., Mitchell, T. R., & Stewart, G. L. (2003). Situational and motivation influences on trait-behavior relationships. In M. R. Barrick & A. M. Ryan (Eds.), Personality and work: Reconsidering the role of personality in organizations. Wiley.

Barrick, M. R., Mount, M. K., & Li, N. (2013). The theory of purposeful work behavior: The role of personality, higher-order goals, and job characteristics. Academy of Management Review, 38(1), 132–153. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2010.0479.

Barrick, M. R., Stewart, G. L., & Piotrowski, M. (2002). Personality and job performance: Test of the mediating effects of motivation among sales representatives. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.87.1.43.

Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B., Walker, S., Christensen, R., . . . & Green, P. (2017). Package ‘lme4’. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lme4/lme4.pdf.

Bauer, D., Preacher, K., & Gil, K. (2006). Conceptualizing and testing random indirect effects and moderated mediation in multilevel models: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 11(2), 142–163. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.142.

Beehr, T., Bowling, N., & Bennett, M. (2010). Occupational stress and failures of social support: When helping hurts. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15, 45–59.

Bowling, N. A., Eschleman, K. J., Wang, Q., Kirkendall, C., & Alarcon, G. (2010). A meta-analysis of the predictors and consequences of organization-based self-esteem. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(3), 601–626. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909X454382.

Brown, A., Colville, I., & Pye, A. (2015). Making sense of sensemaking in organization studies. Organization Studies, 36(2), 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840614559259.

Caplan, R., Cobb, S., French, J., Harrison, R., & Pinneau Jr., S. (1975). Job demands and worker health (pp. 75–160). Washington, DC: H. E. W. Publication No. NIOSH.

Carver, C., Scheier, M., & Weintraub, J. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 267–283.

Cho, S., & Mor Barak, M. (2008). Understanding diversity and inclusion in perceived homogeneous culture: A study of organizational commitment and job performance among Korean employees. Administration in Social Work, 32(4), 100–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/03643100802293865.

Cohen, S. (1992). Stress, social support, and disorder. In H. O. F. Veiel & U. Baumann (Eds.), The meaning and measurement of social support (Chapter 8 (pp. 109–124). Hemisphere.

Conway, J., & Lance, C. (2010). What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25, 325–334.

Crossley, C., Grauer, E., Lin, L., & Stanton, J. (2002). Assessing the content validity of intention to quit scales. Paper presented at the annual meeting of Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Toronto, Canada.

Cutrona, C., & Suhr, J. (1992). Controllability of stressful events and satisfaction with spouse support behaviors. Communication Research, 19, 154–174.

Dougherty, D., & Drumheller, K. (2006). Sensemaking and emotions in organizations: Accounting for emotions in a rational(ized) context. Communication Studies, 57(2), 215–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510970600667030.

Dunbar, R. I. M., Marriott, A., & Duncan, N. D. C. (1997). Human conversational behavior. Human Nature, 8, 231–246.

Dutton, J., Roberts, L., & Bednar, J. (2010). Pathways for positive identity construction at work: Four types of positive identity and the building of social resources. Academy of Management Review, 35(2), 265–293.

Emotional rescue: How to help angry employees vent. (2013). Retrieved from https://www.businessmanagementdaily.com/37000/emotional-rescue-how-to-help-angry-employees-vent.

Feeney, B., & Collins, N. (2015). Thriving through relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology, 1, 22–28.

Fenalson, K., & Beehr, T. (1994). Social support and occupational stress: Effects of talking to others. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15, 157–175.

Grant, A., Dutton, J., & Rosso, B. (2008). Giving commitment: Employee support programs and prosocial sensemaking process. Academy of Management Journal, 51(5), 898–918.

Gross, J., & John, O. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348.

John, O., Naumann, L., & Soto, C. (2008). Paradigm shift to the integrative big-five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, and L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 114–158). Guilford.

Karasek, R. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24, 285–308.

Kim, H., & Kao, D. (2014). A meta-analysis of turnover intention predictors among U.S. child welfare workers. Children and Youth Services Review, 47, 214–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.09.015.

Klep, A., Wisse, B., & Van der Flier, H. (2011). Interactive affective sharing versus non-interactive affective sharing in work groups: Comparative effects of group affect on work group performance and dynamics. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 312–323. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.775.

Knight, A., & Eisenkraft, N. (2015). Positive is usually good, negative is not always bad: The effects of group affect on social integration and task performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(4), 1214–1227. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000006.

Kowalski, R. (2002). Whining, griping, and complaining: Positivity in the negativity. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(9), 1023–1035. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp10095.

Lazarus, R. S. (1999). Hope: An emotion and a vital coping resource against despair. Social Research, 66, 653–678.

Lee, C.-Y. S., & Dik, B. J. (2017). Associations among stress, gender, sources of social support, and health in emerging adults. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 33(4), 378–388.

Lohr, J., Olatunji, B., Baumeister, R., & Bushman, B. (2007). The psychology of anger venting and empirically supported alternatives that do no harm. Scientific Review of Mental Health Practice, 5(1), 53–64.

Luminet, O., Bouts, P., Delie, F., Manstead, A., & Rimé, B. (2000). Social sharing of emotion following exposure to a negatively valenced situation. Cognition and Emotion, 14, 661–668. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930050117666.

Lykken, D. T. (1968). Statistical significance in psychological research. Psychological Bulletin, 70, 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0026141.

Mathieu, M., Eschleman, K. J., & Cheng, D. (2018). Meta-analytic and multiwave comparison of emotional support and instrumental support in the workplace. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000135.

McLeod, L. (n.d.) How to deal with the 5 most negative types of coworkers. Retrieved from https://www.themuse.com/advice/how-to-deal-with-the-5-most-negative-types-of-coworkers.

Meyer, J., Stanley, D., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61, 20–52. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842.

Mitchell, T., & Lee, T. (2001). The unfolding model of voluntary turnover and job embeddedness: Foundations for a comprehensive theory of attachment. Research in Organizational Behavior, 23, 189–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(01)23006-8.

Morrison, R. (2009). Are women tending and befriending in the workplace? Gender differences in the relationship between workplace friendships and organizational outcomes. Sex Roles, 60, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9513-4.

Nils, F., & Rimé, B. (2012). Beyond the myth of venting: Social sharing modes determine the benefits of emotional disclosure. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 672–681. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.1880.

Pearce, J., & Randel, A. (2004). Expectations of organizational mobility, workplace social inclusion, and employee job performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 81–98.

Pearson, C. M. (2017). The smart way to response to negative emotions at work. MIT Sloan Management Review.

Pierce, J., & Gardner, D. (2004). Self-esteem within the work and organizational context: A review of the organization-based self-esteem literature. Journal of Management, 30(5), 591.

Pierce, J. L., Gardner, D. G., Cummings, L. L., & Dunham, R. B. (1989). Organization-based self-esteem: Construct definition measurement and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 622–648.

Podsakoff, P., MacKenzie, S., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Qualtrics (2014). ESOMAR 28: 28 questions to help research buyers of online samples. Retrieved from https://success.qualtrics.com/rs/qualtrics/images/ESOMAR%2028%202014.pdf.

Regts, G., & Molleman, E. (2012). To leave or not to leave: When receiving interpersonal citizenship behavior influences an employee’s turnover intention. Human Relations, 66(2), 193–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726712454311.

Rimé, B. (2007). Interpersonal emotion regulation. In J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (2nd ed., pp. 466–485). Guilford.

Rimé, B. (2009). Emotion elicits the social sharing of emotion: Theory and empirical review. Emotion Review, 1, 60–85.

Rimé, B., Paez, D., Kanyangara, P., & Yzerbyt, V. (2010). The social sharing of emotions in interpersonal and in collective situations: Common psychosocial consequences. In I. Nyklicek, A. Vingerhoets, & M. Zeelenberg (Eds.), Emotion regulation and well-being (pp. 147–163). Springer Science + Business Media.

Rusbult, C. E., Verette, J., Whitney, G. A., Slovik, L. F., & Lipkus, I. (1991). Accommodation processes in close relationships: Theory and preliminary empirical evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(1), 53–78.

Sandberg, J., & Tsoukas, H. (2015). Making sense of the sensemaking perspective: Its constituents, limitations, and opportunities for further development. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36, S6–S32. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1937.

Selig, J., & Preacher, K. (2008). Monte Carlo method for assessing mediation: An interactive tool for creating confidence intervals for indirect effects [computer software]. Available from http://quantpsy.org/.

Sherony, K., & Green, S. (2002). Coworker exchange: Relationships between coworkers, leader=member exchange, and work attitudes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 542–548. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.87.3.542.

Sias, P., Heath, R., Perry, T., Silva, D., & Fix, B. (2004). Narratives of workplace friendship deterioration. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 21(3), 321–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407504042835.

Simpson, P., & Stroh, L. (2004). Gender differences: Emotional expression and feelings of personal inauthenticity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(4), 715–721. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.4.715.

Snijders, T., & Bosker, R. (1993). Standard errors and sample sizes for two-level research. Journal of Educational Statistics, 18, 237–260.

Spector, P. (1994). Using self-report questionnaires in OB research: A comment on the use of a controversial method. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15, 385–392.

Spector, P., Bauer, J., & Fox, S. (2010). Measurement artifacts in the assessment of counterproductive work behavior and organizational citizenship behavior: Do we know what we think we know? Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(4), 781–790.

StataCorp. (2015). Statistical software: Release 14. College Station: StataCorp LP.

Stone-Romero, E., & Rosopa, P. (2004). Inference problems with hierarchical multiple regression-based tests of mediating effects. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 23, 249–290.

Suhr, J., Cutrona, C., Krebs, K., & Jensen, S. (2004). The social support behavior code. In P. Kerig & D. Baucom (Eds.), Couple observational coding systems (pp. 311–318). Erlbaum.

Tett, R., & Burnett, D. (2003). A personality trait-based interactionist model of job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 500–517. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.500.

Turner, N. (2017). Social relations in and around work. Human Relations, 70(1), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726716678367.

Van Katwyk, P., Fox, S., Spector, P., & Kelloway, K. (2000). Using the Job-related Affective Well-being Scale (JAWS) to investigate affective responses to work stressors. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 219–230.

Venkataramani, V., Labianca, G., & Grosser, T. (2013). Positive and negative workplace relationships, social satisfaction, and organizational attachment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(6), 1028–1039. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034090.

Weick, K. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Wiggins, J. S., & Trapnell, P. D. (1996). A dyadic-interactional perspective on the five-factor model. In J. S. Wiggins (Ed.), The five-factor model of personality: Theoretical perspectives (pp. 88–162). Guilford.

Wrzesniewski, A., Dutton, J., & Debebe, G. (2003). Interpersonal sensemaking and the meaning of work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 25, 93–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(03)25003-6.

Cheung, J. H., Burns, D. K., Sinclair, R. R., & Sliter, M. (2017). Amazon Mechanical Turk in organizational psychology: An evaluation and practical recommendations. Journal of Business and Psychology, 32(4), 347–361.

Tabachnick, B., & Fidell, L. (2006). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Inc: Pearson Education.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Morgan Robertson and Aaron Van Groningen for their assistance with the early stages of this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 142 kb)

Appendix

Appendix

Pilot data on this measure were collected from 297 participants on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (after data cleaning; total N before data cleaning = 409). We took recommended steps to ensure data quality, for instance by requesting participants with high approval ratings and by including checks for careless responding (Cheung, Burns, Sinclair, & Sliter, 2017). Half of the participants were female (51.4%), and on average, they were around 34 years old (SD = 10.17, range = 18–65 years). Participants reported an average yearly income of $40,838 (range = $3000–$225,000) and working 42.51 h a week (SD = 7.10, range = 15–85). The average time spent working for a current employer was about 5 years (SD = 4.92, range = < 1–32 years), and most participants were not serving in a management position (70.1%). Finally, most participants had a college degree (48.3%); 27.7% had some college education, 10.6% had either some high school or a high school degree, and 13% reported earning a master’s degree or some type of a professional degree.

The purpose of the pilot study was to identify the best-performing items to select and include as part of a brief measure of positive and negative listener reactions as well as to assess construct validity. We identified the highest loading items in an exploratory factor analysis using the .70 factor loading cutoff as the decision criteria (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2006). This resulted in 12 positive listener reaction items and 6 negative listener reaction items. Notably, the 12 highest loading positive listener reactions loaded across three different factors in the EFA while all 6 of the negative listener reactions loaded on a single factor. Recognizing the possibility that the positive listener reaction measure could be separated into three subscales (capturing emotionally oriented positive responses, informationally oriented positive responses, and validation), we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis using the 12 positive items and the 6 negative items. Findings indicated acceptable fit for the four-factor model (X2(129) = 300.16, p < .001; CFI = .94, RMSEA = .073 (.063, .084), SRMR = .047).

However, previous theory and research on listener reactions and interpersonal cues suggests that listener reactions of the same valence (e.g., listener reactions that are all generally positive) could be combined into a higher-order factor as they essentially reflect the same overall affirmation appraisal (e.g., Suhr et al., 2004; Wrzesniewski et al., 2003). Additionally, recent meta-analytic findings in the social support literature suggest that emotional and instrumental supports (related to the emotionally oriented and information-oriented positive listener reactions, respectively) are strongly related across the literature (ρ = .73; Mathieu et al., 2018), suggesting that these constructs are quantitatively similar. Since our own factor correlations indicated significantly strong correlations among the positive listener reaction factors (ranging from r = .45–.61), suggesting the possibility of an overall affirmation interpretation of the positive interpersonal cues, we tested a factor structure where the three lower-order positively valenced listener reactions were loaded onto a positive second-order factor. All negatively valenced items remained loaded onto the negative listener reaction factor (representing the overall disaffirmation cue). Findings indicated acceptable fit for the second-order model (X2(131) = 315.07, p < .001; CFI = .94, RMSEA = .075 (.065, .086), SRMR = .068). Thus, we maintained the second-order factor structure to best reflect both theoretical and methodological considerations of our measure of affirming interpersonal cues (i.e., positive listener reactions). The reliabilities for both the positive (α = .93) and negative (α = .90) listener reaction measures were satisfactory.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reynolds-Kueny, C., Shoss, M.K. Sensemaking and Negative Emotion Sharing: Perceived Listener Reactions as Interpersonal Cues Driving Workplace Outcomes. J Bus Psychol 36, 461–478 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-020-09686-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-020-09686-4