Abstract

Stamm’s Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL) was utilized to examine compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction among three types of caregivers: formal (employed in a caregiver role), adult child (caring for an aging parent), and spouse/partner (caring for significant other). Data were collected from a sample of 87 adults who were currently (for 6 months or longer) providing care to an individual 65 years of age or older. The results revealed that formal caregivers had significantly higher compassion satisfaction scores compared to both adult child and spouse/partner caregivers. Additionally, results indicated that formal caregivers had significantly lower compassion fatigue scores than adult child caregivers. Although limited by the homogeneities in the sample of convenience, this study suggests that family caregivers could benefit from additional support in providing care. Furthermore, research should be conducted to examine factors that contribute to formal caregivers’ increased satisfaction and decreased fatigue in an effort to inform family caregivers.

Similar content being viewed by others

In the United States (U.S.), the number of individuals 65 years old and over is projected to reach 83.7 million by 2050 (Ortman et al. 2014). By 2030, 20% of the U.S. population will be 65 years old or older. The increase in the number of individuals over the age of 65 may have serious consequences for the entire nation, ranging from changes in home life to new economic challenges (Hayutin et al. 2010). With increased age comes an increased risk for developing challenging restrictions including chronic medical conditions (Alosco et al. 2012), inhibited physical and mental health well-being (Bliwise et al. 2011), increased dependence on others, and a greater need for health services (Sands et al. 2006). Often the potential challenges associated with aging are found in concordance with each other. For instance, with age comes a decrease in physical activity. Alosco et al. (2012) found a relationship between reduced physical activity and depression. Thus, the elderly may be more likely to experience depression in conjunction with a decrease in physical activity compared to their younger counterparts. Moreover, older adults who live without necessary assistance have higher rates of hospital admissions than those who receive assistance (Sands et al. 2006).

The rise in the size of the older population also leads to an increase in the number of people who have dementia, which is expected to double from 4.3 million in 2010 to 11.4 million by 2050 (Hayutin et al. 2010). This increase in the number of individuals with dementia will likely lead to increased demand for caregivers. While not all caregivers experienced negative outcomes from caregiving, some reported emotional, physical, and financial issues after being in the role for 5 years (National Alliance for Caregiving 2009). When asked to rate the emotional stress of caregiving, 31% of caregivers reported that caregiving was very stressful, and almost half of the caregivers sampled (47%) rated their health as poor to fair (National Alliance for Caregiving 2009). This highlights the importance in identifying compassion fatigue, characterized by burnout and secondary traumatic stress, and compassion satisfaction, the counterpart to fatigue (Stamm 2010).

Both responses arising from compassion (fatigue and satisfaction) can be experienced by caregivers simultaneously. Shim et al. (2010) utilized qualitative data gathered over the course of 57 interviews with 21 spousal caregivers caring for someone with Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease. Participants were asked to describe three negative and three positive aspects of caregiving experienced within the previous month. Caregivers’ responses were separated into three groups: negative, ambivalent, and positive. The negative group was characterized by the view that the relationship with the care recipient was poor due to the care recipient’s negative behavior, the inability to describe a positive caregiving experience, or a lack of empathy and interest in the spouse’s condition. The ambivalent caregiver group found that their relationship with the care receiver was mostly positive, but still missed the person that was once their spouse. The combination of the changing relationship dynamic and the unpredictable and inconsistent behaviors of their spouses contributed to mixed feelings about caregiving. Conversely, the caregivers in the positive group were living in the present with their spouses, rather than being concerned with who they once were. These spouses appreciated and accepted their spouses and the time they had left to spend together (Shim et al. 2010).

Another study looked at the perceived quality of life of patients by comparing data from the patients themselves, spousal caregivers, and adult child caregivers (Conde-Sala et al. 2010). The results found that spousal caregivers had a more positive perception of the patients’ quality of life than adult child caregivers. In addition, the persons being cared for indicated a preference for spousal caregivers. It was suggested that spousal caregivers could be more likely to consider the task of caring as part of their marital commitment and would be physically and emotionally closer to the patient. In addition, despite taking on this role in old age, it could give meaning and purpose to their lives. Adult child caregivers on the other hand were believed to experience generational differences and feel more distant emotionally. Additionally, they likely had to combine other obligations such as family and work (Conde-Sala et al. 2010).

While the aforementioned study focused on the perceived quality of life of the care recipient, it is essential to understand the quality of life of the caregiver. As Conde-Sala et al. (2010) suggested, it is important to improve caregiver quality of life and advocate for family caregivers (Wiles 2003). Moreover, Litzelman et al. (2014) suggested caregiver strain with caregiver subgroups such as spousal support and that of close family members.

Crowther et al. (2014) recorded the personal experiences of bereaved caregivers of a close family member that suffered from dementia. The results suggested that caregiver compassion fatigue had immediate consequences and long-lasting effects. Furthermore, caregivers’ confidence in their ability to provide adequate care influenced how they viewed the caregiving experience. It further affected caregiver susceptibility to developing depressive symptoms and increased the risk of developing compassion fatigue. Past research has also identified value in comparing informal (or familial) and formal care for the elderly (Lyons et al. 2000).

Research into formal caregiving has revealed that some caregivers are more vulnerable to the physical and mental implications of caregiving (Abendroth and Flannery 2006). Among 216 hospice nurses, those who were self-sacrificing for patients were found to be at greater risk for developing compassion fatigue. In addition, they were more likely to partake in smoking, experience financial stress, and suffer from headaches and hypertension. Abendroth and Flannery (2006) believed this type of caring comes from an excess of empathy. This level of investment in caregiving was considered a result of wavering boundaries between family and work, which put nurses at a higher risk for developing compassion fatigue (Abendroth and Flannery 2006).

A phenomenological-hermeneutic study of formal caregivers for those with aggressive behavior in dementia suggested a need for balance and support (Skovdahl et al. 2003). Furthermore, caregivers who master caregiving skills and their implementation could be more successful at reducing distressing behaviors than caregivers that only act in a custodial role (Skovdahl et al. 2003). Additionally, Gilliam and Steffen (2006) identified a direct relationship between self-efficacy and depressive symptoms within caregivers. There was no evidence suggesting that there was a moderating relationship; even after accounting for high levels of cognitive impairment in the care recipient, the relationship between caregivers’ self-efficacy and depression was unchanged (Gilliam and Steffen 2006). Fundamentally, it is important to establish an appropriate balance of supportive behaviors beneficial to the care recipient and caregiver (Gopalan et al. 2012).

Although caregiving can result in compassion fatigue, there is evidence that protective factors can combat compassion fatigue among caregivers. Gallagher et al. (2011) measured the abilities of 84 caregivers to cope with the strain of caregiving, self-efficacy, and self-reported depressive symptoms. The findings revealed a negative correlation between self-efficacy and caregiver depression. For instance, with an increase in self-efficacy, the risk of depression decreased. A caregiver’s symptom management, education level, neuroticism, coping style, and patient function all contributed to caregiver depression. Additionally, high caregiver burden contributed to caregivers’ depressive symptoms (Gallagher et al. 2011). Likewise, caregivers who experienced care burden and depression had a lower relationship quality with the care recipient (Davis et al. 2011).

In order to care for both the aging population and caregivers, it is critical to better understand the needs of caregivers. Although caregiving generally involves compassion towards another human being, there are many stressful aspects to caregiving. Crowther et al. (2014) suggested that compassion is characterized by an understanding of the emotional state of another. There are two responses that arise from feeling compassion: compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction. Both of these terms have been defined in the Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL; Stamm 2010). The ProQOL is used to measure positive and negative elements of caregiving to elicit quantitative measures of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue.

Compassion satisfaction refers to the pleasurable feelings that come from caregiving (Stamm 2010). In prior literature, the beginning stage of compassion fatigue was coined compassion stress and was characterized by caregivers’ inability to free themselves from the negative emotions of caregiving (Perry et al. 2010). Caregiving can have immediate and long-term effects; therefore, compassion fatigue is broken down into two categories: burnout and secondary trauma. Burnout is associated with negative effects experienced when an individual is actively engaged in the role of caregiver (i.e., frustration at the job). Secondary trauma occurs when the negative aspects of caregiving extend beyond the realm of care, such as experiencing disturbed sleep for a prolonged period of time as a result of caregiving.

Although the volume of research on compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction is increasing, limited information exists regarding possible differences between caregiver types. Therefore, the purpose of this research study was to explore compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue for three different types of caregivers providing care for aging populations (65 years old or older). The types of caregivers were formal (employed in a caregiver role), adult child (caring for an aging parent), and spouse/partner (caring for a significant other). The ProQOL (Stamm 2010) was specifically selected because it is free and available to the public as a self-scored tool. Therefore, individuals could track their own satisfaction or fatigue to manage self-care. Moreover, mental health practitioners could use the instrument to examine the emotional state of caregivers and develop interventions for fatigue. Additionally, with the size of the aging population on the rise (Ortman et al. 2014), it is important to further examine caregiver compassion fatigue and satisfaction.

The research questions and hypotheses were as follows. Research Question 1 was: Does the level of compassion fatigue differ for the different types of caregivers (spouse, adult child, or formal caregiver)? Hypothesis 1 postulated that compassion fatigue would differ between the different types of caregivers. Research Question 2 was: Does the level of compassion satisfaction differ for the different types of caregivers (spouse, adult child, or formal caregiver)? Hypothesis 2 proposed that the level of compassion satisfaction would differ among the different types of caregivers. The hypotheses were non-directional in order to be receptive to effects going in either direction for each caregiver type.

Method

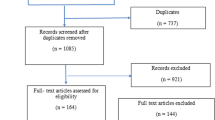

The three types of caregivers on which this research was focused were (a) formal caregivers (employed in a caregiver role), (b) adult children (caring for an aging parent), and (c) spouse/partner caregivers (caring for a significant other). Following IRB approval, participants were recruited from a sample of convenience located primarily in the Midwest (but not limited to the Midwest). Recruitment occurred through flyers, emails, social media, and snowball referral techniques. Once identified, potential participants were directed to an anonymous online survey. An informed consent form that indicated the purpose of the study and the inclusion criteria was presented prior to the online survey. The inclusion criteria established for this study were that participants must be 18 years of age or older, have Internet access, be able to read and comprehend eighth grade English, and be currently (for 6 months or longer) providing care to an individual 65 years of age or older. Caregivers then selected the role that best described them in the demographic questionnaire. The demographic questionnaire included other basic information such as the caregiver’s age, education level, and household income.

This research study consisted of a quantitative (online) survey research design. The instrument used was the Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL; Stamm 2010), a 30-item questionnaire with a 5-point Likert scale regarding compassion fatigue (characterized by burnout and secondary trauma), and compassion satisfaction. Professional quality of life comprises the qualities that a person feels in relation to working as a helper. This incorporates two aspects: the positive (compassion satisfaction) and the negative (compassion fatigue). Cronbach’s alpha reliability analysis procedure was used to examine reliability of the measure for this study (Tabachnick and Fidell 2007). Scale reliability was assumed if the coefficient was ≥ .70. Results from the test found sufficient reliability for the dependent variables: compassion satisfaction (.907), burnout (.845), and secondary traumatic stress (.831). Results from the test found that the variable constructs were sufficiently reliable. Thus, the variable constructs did not violate the assumption of reliability and were used to evaluate the research questions. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS; version 23.0 2015) was used to further analyze the data.

Results

Prior to analyzing the research questions, data cleaning and data screening were undertaken to ensure the variables of interest met appropriate statistical assumptions. Thus, the following analyses were assessed using an analytic strategy in that the variables were first evaluated for missing data, univariate outliers, normality, homogeneity of variance, and multicollinearity. Finally, MANOVA analysis was run to test the two research questions.

Demographics

Data were collected from a valid sample of 87 adults that were currently (for 6 months or longer) providing care to an individual who was 65 years of age or older. Specifically, 48.3% of participants were adult–child caregivers (n = 42), 34.5% were formal caregivers (n = 30), and 17.2% were spousal/partner caregivers (n = 15). The majority of participants were female (95.4%, n = 84) and the remaining four participants were male (4.6%, n = 4). Additionally, 95.4% of the participants were White (n = 83), 2.3% were Black/African American (n = 2), and 2.3% were from multiple ethnicities (n = 2). Out of the 87 valid participants, the majority (n = 71) were between 30 and 69 years of age. That is, 11 were between 30 and 39 years old (12.6%, n = 11), 19 were between 40 and 49 (21.8%, n = 19), 30 were between 50 and 59 years old (34.5%, n = 30), and 11 were between 60 and 69 years old (12.6%, n = 11). Furthermore, five participants’ highest level of education was a high school degree/GED (5.7%, n = 5), 24 attended some college but did not receive a degree (27.6%, n = 24), seven had an associate degree (8.0%, n = 7), 25 had a bachelor’s degree (28.7%, n = 25), and 26 had a graduate degree (29.9%, n = 26).

Analysis of Research Questions 1 and 2

Research questions 1 and 2 were evaluated using MANOVA analysis to determine if any significant differences in caregivers’ quality of life existed between caregiver types, age groups, and level of education. The dependent variables were three quality of life subscales including compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress (compassion fatigue) as measured by the 30-item Professional Quality of Life Scale—Compassion Satisfaction and Compassion Fatigue Version 5 (PROQOL). The three quality of life subscales were measured by ten items each on the PROQOL and response parameters were measured on a 5-point scale, where 1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, and 5 = very often. Composite scores were calculated by summing case scores across the three subscales’ 10-item constructs resulting in a possible range of scores between 10 and 50. That is, higher scores on the compassion satisfaction subscale indicated higher levels of compassion satisfaction. Whereas, lower scores on the remaining two subscales (burnout and secondary traumatic stress) indicated higher levels of quality of life.

The independent variables were participants’ caregiver type, age, and level of education. Participants were categorized into three types of caregivers including formal caregivers (employed in a caregiver role n = 30), adult child (caring for an aging parent n = 42), and spouse/partner caregivers (caring for a significant other n = 15). Furthermore, due to low sample sizes across age groups, participants were placed into two groups including those that were between 18 and 49 years old (n = 39) and those that were 50 years and older (n = 48). Similarly, participants were placed into two educational groups including those with a high school degree/GED, some college experience, or an associate degree (associate degree or less n = 36) and those with a bachelor’s degree and/or graduate degree (bachelor’s degree or higher n = 51).

Data Cleaning

A valid sample of 87 caregivers participated in the current study. Before the data were evaluated, the data were screened for missing data, univariate outliers, and multivariate outliers. Missing data were investigated using frequency counts and no cases were found. The data were screened for univariate outliers by transforming raw scores to z-scores and comparing z-scores to a critical range between − 3.29 and + 3.29, p < .001 (Tabachnick and Fidell 2007). Z-scores that exceed this critical range are more than three standard deviations away from the mean and thus represent outliers. The distributions were evaluated and no cases with univariate outliers were found.

Multivariate outliers were evaluated using Mahalanobis distance. Mahalanobis distances were computed for each variable and these scores were compared to a critical value from the chi-square distribution table. Mahalanobis distance for three dependent variables indicates a critical value of 16.27. Results indicated that no cases within the distributions were found to exceed these values. Thus, 87 responses from participants were received and 87 were evaluated by the MANOVA model for research questions 1 and 2 (N = 87).

Normality

Before the research questions were analyzed, basic parametric assumptions were assessed. That is, for the dependent variable (compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress), assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were tested. To test if the distributions were normally distributed, the skew and kurtosis coefficients were divided by the skew/kurtosis standard errors, resulting in z-skew/z-kurtosis coefficients. This technique was recommended by Tabachnick and Fidell (2007). Specifically, z-skew/z-kurtosis coefficients exceeding the critical range between − 3.29 and + 3.29 (p < .001) may indicate non-normality. Thus, based on the evaluation of the z-skew/z-kurtosis coefficients, no distribution was found to be significantly skewed or kurtotic. Therefore, the assumption of normality was not violated, and the distributions were assumed to normally distributed.

Homogeneity of Variance

Levene’s test of equality of error variance was run to determine if the error variances of the dependent variables (compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress) were equal across levels of the independent variables (type of caregivers, age groups, and level of education). Results indicated that one of the distributions did violate the assumption of homogeneity of variance, burnout F(9, 77) = 2.165, p = .034. Thus, non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests were conducted across the distribution, burnout, to affirm the results of the MANOVA analysis. Results from the remaining dependent variables suggested that the error variances were equally distributed across levels of the independent variables and did not violate the assumption of homogeneity (p > .05).

Homogeneity of Variance–Covariance Matrices

To examine the assumption of homogeneity of variance–covariance matrices, Box’s M test of equality of covariance matrices was conducted. The test was run to determine if the distributions of the dependent variables (compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress) were equal across the levels of the independent variable (type of caregivers, age groups, and level of education). The critical value determining violation of the assumption is p < .001. Results from the test found that the distributions were equal across the dependent variables, Box’s M = 96.369, F(48, 2961.775) = 1.629, p = .004. Therefore, the assumption of homogeneity of variance–covariance matrices was not violated.

Multicollinearity

The assumption of multicollinearity was tested by calculating correlations between dependent variables (compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress) using collinearity statistics (correlations, tolerance, and variance inflation factor). Correlations between dependent variables did not exceed .80. Additionally, tolerance was calculated using the formula T = 1 − R2 and variance inflation factor (VIF) was the inverse of tolerance (1 divided by T). Commonly used cut-off points for determining the presence of multicollinearity are T < .10 and VIF > 10. Results indicated that tolerance and VIF coefficients did not exceed the critical values.

MANOVA

Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to determine if any significant differences in participants’ quality of life subscale scores existed between caregiver types, age groups, and level of education. Results indicated that there were significant multivariate difference between caregiver types on a model containing three dependent variables, Wilks’ λ = 0.724, F(6, 150) = 4.375, p < .001, η2 = .149. Additionally, there was a significant multivariate interaction between the three independent variables (caregiver types, age groups, and level of education) on the model containing three quality of life subscales, Wilk’s λ = 0.893, F(3, 75) = 3.003, p = .036, η2 = .107. Furthermore, results from the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests did not differ from those of the MANOVA analysis; therefore, the results of the MANOVA analysis were used to evaluate hypotheses 1 and 2. A model summary of the multivariate MANOVA results is displayed in Table 1 in Appendix 1.

Results from the individual between-subject effects test further indicated significant differences in participants’ quality of life subscale scores (compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress) existed between caregiver types (formal, adult–child, and spouse–partner). That is, there were significant differences between caregiver types and their scores on compassion satisfaction (p = .006), burnout (p < .001), and secondary traumatic stress (p = .004). No other significant differences were found in the MANOVA test of between-subject effects.

Results from the Tukey HSD post hoc analysis revealed that formal caregivers had significantly higher compassion satisfaction scores (M = 42.033, SD = 5.991) compared to both adult–child (p < .001, M = 34.714, SD = 7.079) and spouse/partner (p < .001, M = 33.533, SD = 5.854). Additionally, results indicated that formal caregivers had significantly (p < .001) lower burnout scores (M = 21.267, SD = 6.034) compared to adult–child caregivers (p < .001, M = 28.548, SD = 7.041). Lastly, the post hoc analysis indicated that formal caregivers had significantly lower secondary traumatic scores (M = 20.700, SD = 6.232) compared to adult–child caregivers (p = .001, M = 26.476, SD = 6.780) and spouse/partner caregivers (p = .032, M = 26.067, SD = 7.035). A means plot of participants’ quality of life scores by caregiver types is displayed in Fig. 1 in Appendix 2.

Discussion

The findings indicated a significantly higher compassion satisfaction score for formal caregivers that were employed in a caregiver role. Moreover, adult child caregivers caring for an aging parent and spouse/partner caregivers had significantly higher burnout and secondary trauma scores (which characterize compassion fatigue). These findings present several important discussion points.

Perhaps, knowing the higher level of satisfaction experienced by professional caregivers will be a relief for family members who experience guilt when asking for help in providing care. Furthermore, results regarding the higher compassion fatigue for family caregivers may help family members know that they are not alone in feeling like caregiving is a difficult process. Understanding that others in this role also feel that way could empower them to seek out the support that is needed to cope with burnout and/or secondary trauma. For instance, Rote et al. (2015) examined elderly Mexican Americans and family caregivers, a rapidly growing segment of the aging population. The results suggested that low-income caregivers were especially vulnerable to psychological distress. Mobility limitations and social disability also impacted caregiver distress. In addition, females seemed more susceptible to depressive symptoms when caring for a male with aggressive outbursts. Moreover, these vulnerabilities could be the focus of intervention efforts (Rote et al. 2015).

Additionally, there could be factors that are transferrable to the family caregivers from the experiences of formal caregivers. For example, helping in shifts could be a factor that is transferrable from formal caregiving to family caregiving. Further research should be conducted to examine factors that could increase the satisfaction of family caregivers. Formal caregivers may feel they have more success because the caretaking responsibility is spread across several people, whereas spousal or adult children bear the majority or all of the responsibility. In addition, if something goes wrong in a formal caregiving situation, responsibility can be shared, whereas, in informal caregiving all of the additional weight is often placed on one family member. Therefore, it may be useful to help family caregivers create a schedule and share responsibilities when appropriate.

Scheduling and planning could be important to consider when examining compassion fatigue and satisfaction. For instance, previous research related to formal caregivers identified shift placement as a factor in fatigue (Smart et al. 2014). For example, working certain shifts (night shift or extended hours) contributed to low compassion satisfaction and high fatigue. Based on the results of this study and earlier research into compassion fatigue and satisfaction, there is evidence that a healthy work environment can prevent or reduce compassion fatigue in formal caregivers (Smart et al. 2014). Furthermore, the findings related to formal caregiving should be further explored to enhance the compassion satisfaction for adult children and spouses/partners providing care. Another factor might be the formal caregivers’ education level. As a result of education, formal caregivers develop coping skills and competency, whereas informal caregivers may not. Another component to consider is that formal caregivers have the opportunity to choose to provide care, whereas adult child and spousal caregivers tend to have less free will in the decision. Further, levels of compassion fatigue may be greater in adult child and spousal caregivers because of the emotional turmoil that accompanies watching a loved one age.

While much could be learned from formal caregivers, it is important to recognize double-duty caregivers. That is healthcare professionals juggling employment and informal caregiving (Boumans and Dorant 2014). The results of a questionnaire indicated that as professional healthcare workers provide more hours of informal care in their private lives, their mental and physical health significantly worsens. More specifically, emotional exhaustion, and negative experiences with work–home and home–work interferences. Therefore, double-duty caregivers are at risk to developing symptoms of overload. Boumans and Dorant call for special attention, with long-term solutions at both legislative and organizational levels (2014).

Moreover, the professional quality of life instrument used for this study (ProQOL; Stamm 2010) could be utilized by caregivers to monitor fatigue and satisfaction with the self-score option. This could help individuals better understand the nuances of burnout and secondary traumatic stress. It is important for caregivers to receive adequate support not just for their own well-being but also for that of the person receiving care.

Limitations

The primary limitation to this study was the sample of convenience. This produces problems with respect to external validity and the results may not be generalizable. In addition, the gender and race of the participants were homogenous (the majority was female and White). As a result, this study should be replicated with a larger and more diverse sample. Methodological limitations include the reliance on self-selection, self-reported data, and administering the study via the Internet only. This could limit accessibility given that one participant group (spousal caregivers) on which the study was focused is likely in an older demographic and may have some discomfort with Internet use. Moreover, the spouse/partner group had fewer participants. Additional data should be collected on this group for analysis and perhaps paper/pencil surveys would add ease of access for this demographic.

Recommendations

In order to assess all caregiver subtypes in the future, it would be useful to look into the nature of care recipients’ needs, the number of people for whom a caregiver provides, and whether there is shared care. Specific to familial caregivers, qualitative research could further explore reasons for fatigue in adult child and spouse/partner caregivers. Strategies for prevention of burnout and secondary trauma should be explored and presented to those experiencing compassion fatigue. Future research should look at the intensity of the caregiving situation, risks, and resources (Rote et al. 2015). Moreover, future research should take into consideration the compassion satisfaction and fatigue of young adult children and grandchildren in the role of primary caregivers for older relatives (Dellmann-Jenkins et al. 2000).

Furthermore, future research could examine how caregiver embarrassment, guilt, and shame relate to well-being, the type of care given, and willingness to accept and seek help from family or formal caregivers. It may also be useful to evaluate the impact of a strength-based approach for family caregivers in a therapeutic setting or to explore the impact of social support or group therapy interventions. Consequently, it is important to examine how to make caregiving more manageable mentally, physically, and financially.

Kalwij et al. (2014) also suggest that attention be given to additional informal home care providers such grandchildren and friends. For instance, single elderly persons may rely more on care from friends and neighbors. Therefore, policy makers should take into account not only home care provision from adult children, but also care from friends and neighbors to obtain accurate projections regarding increasing costs of care due to an aging population (Kalwij et al. 2014).

Conclusion

The professional quality of life for those providing care has been a topic of growing interest over the past 20 years (Stamm 2010). The aim of this research study was to better understand compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue among those caring for aging populations. The findings revealed a higher level of compassion fatigue (burnout and secondary trauma) for adult children and spouse/partner caregivers than for formal caregivers. This demonstrated a need to better understand the caregiving experience for the three participant groups, all of which are central for eldercare. Furthermore, additional research needs to focus on this area to identify an empirically supported understanding of the interaction between the health and well-being of the elderly and their caregivers and how to enhance satisfaction and prevent fatigue. The projected increase in the late adulthood population raises concerns for the health not just of these individuals, but also for their caregivers. It is important for mental health professionals to encourage the aging population to participate in healthy aging practices and to empower caregivers to communicate their needs, manage self-care, and receive adequate support.

References

Abendroth, M., & Flannery, J. (2006). Predicting the risk of compassion fatigue: A study of hospice nurses. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2010.06.006.

Alosco, L. M., Spitznagel, M. B., Miller, L., Raz, N., Cohen, R., Sweet, H. L., … Gunstad, J. (2012). Depression is associated with reduced physical activity in persons with heart failure. Health Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028711.

Bliwise, D. L., Mercaldo, N. D., Avidan, A. Y., Boeve, B. F., Greer, S. A., & Kukull, W. A. (2011). Sleep disturbance in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease: A multicenter analysis. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1159/000326238.

Boumans, N., & Dorant, E. (2014). Double-duty caregivers: Healthcare professionals juggling employment and informal caregiving. a survey on personal health and work experiences. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(7), 1604–1615. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12320.

Conde-Sala, J. L., Garre-Olmo, J., Turró-Garriga, O., Vilalta-Franch, J., & Lópex-Pousa, S. (2010). Quality of life of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: Differential perceptions between spouse and adult child caregivers. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1159/00027242.

Crowther, J., Wilson, K. C., Horton, S., & Lloyd-Williams, M. (2014). Compassion in healthcare: Lessons from a qualitative study of the end of life care of people with dementia. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076813503593.

Davis, L. L., Gilliss, C. L., Deshefy-Longhi, T., Chestnutt, D. H., & Molloy, M. (2011). The nature and scope of stressful spousal caregiving relationships. Journal of Family Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840711405666.

Dellmann-Jenkins, M., Blankemeyer, M., & Pinkard, O. (2000). Young adult children and grandchildren in primary caregiver roles to older relatives and their service needs. Family Relations, 49(2), 177–186.

Gallagher, D., Mhaolain, A. N., Crosby, L., Ryan, D., Lacey, L., Coen, R. F., … Lawlor, B. A. (2011). Self-efficacy for managing dementia may protect against burden and depression in Alzheimer’s caregivers. Aging & Mental Health, 15(6), 663–670.

Gilliam, C. M., & Steffen, A. M. (2006). The relationship between caregiving self-efficacy and depressive symptoms in dementia family caregivers. Aging & Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860500310658.

Gopalan, N., Miller, M. M., & Brannon, L. A. (2012). Motivating adult children to provide support to a family caregiver. Stress Health. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2480.

Hayutin, A. M., Dietz, M., & Mitchell, L. (2010). New realities of an older America: Challenges, changes and questions. Stanford Center on Longevity. http://longevity3.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/New-Realities-of-an-Older-America.pdf.

Kalwij, A., Pasini, G., & Wu, M. (2014). Home care for the elderly: The role of relatives, friends and neighbors. Review of Economics of the Household, 12(2).

Litzelman, K., Skinner, H. G., Gangnon, R. E., Nieto, F. J., Malecki, K., & Witt, W. P. (2014). The relationship among caregiving characteristics, caregiver strain, and health-related quality of life: Evidence from the Survey of Health Wisconsin. Quality of Life Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0874-6.

Lyons, K. S., Zarit, S. H., & Townsend, A. L. (2000). Families and formal service usage: Stability and change in patterns of interface. Aging and Mental Health, 4(3), 234–243.

National Alliance for Caregiving in Collaboration with AARP. (2009). Caregiver in the U.S.: A focused look at those caring for someone age 50 or older. http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/il/caregiving_09_es50.pdf.

Ortman, J. M., Velkoff, V. A., & Hogan, H. U. S. (2014). An aging nation: The older population in the United States (Report No. P25-1140). United States Census Bureau. http://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf.

Perry, B., Dalton, J. E., & Edwards, M. (2010). Family caregivers’ compassion fatigue in long-term facilities. Nursing Older People. https://doi.org/10.7748/nop2010.05.22.4.26.c7734.

Rote, S., Angel, J. L., & Markides, K. (2015). Health of elderly Mexican American adults and family caregiver distress. Research on Aging. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027514531028.

Sands, L. P., Wang, Y., McCabe, G. P., Jennings, K., Eng, C., & Covinsky, K. E. (2006). Rates of acute care admissions for frail older people living with met versus unmet activity of daily living needs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00590.x.

Shim, B., Barroso, J., & Davis, L. L. (2010). A comparative qualitative analysis of stories of spousal caregivers of people with dementia: Negative, ambivalent, and positive experiences. International Journal of Nursing Studies. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.09.003.

Skovdahl, K., Kihlgren, A. L., & Kihlgren, M. (2003). Different attitudes when handling aggressive behaviour in dementia–narratives from two caregiver groups. Aging & Mental Health, 7(4), 277–286.

Smart, D., English, A., James, J., Wilson, M., Daratha, K. B., Childers, B., & Magera, C. (2014). Compassion fatigue and satisfaction: A cross-sectional survey among US healthcare workers. Nursing and Health Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12068.

Stamm, B. H. (2010). The concise ProQOL manual (2nd ed.). Pocatello, ID: ProQOL.org. http://www.proqol.org/uploads/ProQOL_Concise_2ndEd_12-2010.pdf.

Tabachnick, B., C. & Fidell, L., S (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Wiles, J. (2003). Informal caregivers’ experiences of formal support in a changing context. Health and Social Care in the Community, 11(3), 189–207.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thorson-Olesen, S.J., Meinertz, N. & Eckert, S. Caring for Aging Populations: Examining Compassion Fatigue and Satisfaction. J Adult Dev 26, 232–240 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-018-9315-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-018-9315-z