Abstract

This work describes the geochemical and hydrogeological characteristics of Santa Cesarea Terme, an active sulfuric acid speleogenetic system located along the Adriatic coastline (Apulia, southern Italy). It represents a very peculiar site, where rising thermal and acidic waters mix with seawater creating undersaturated solutions with respect to CaCO3, able to dissolve and corrode limestone and create caves. The Santa Cesarea Terme system is composed of four caves: Fetida, Sulfurea, Gattulla, and Solfatara. Hypogene morphologies and abundant deposits of native sulfur (especially in Gattulla Cave) and sulfate minerals are present in these caves. Fetida and Gattulla caves were investigated primarily because they are easily accessible throughout the whole year through artificial entrances, the other caves being reachable only from the sea. Geochemical analysis of water, monitoring of cave atmosphere, and measurement of the stable isotopes of S, O, and H helped to identify the main processes occurring in this complex cave system. In particular, changes in Ba2+ and Sr2+ concentration allowed for the identification of two main domains of influence, characterized by marine and rising acidic waters.

Résumé

Ce travail décrit les caractéristiques géochimiques et hydrogéologiques des thermes de Santa Cesarea, un système actif spéléogénétique sulfurique acide situé le long de la côte adriatique (Pouilles, Sud de l’Italie). Il représente un site très particulier, où l’eau thermale émergeant et les eaux acides se mélangent à l’eau de la mer créant des solutions sous saturées vis-à-vis du CaCO3, capables de dissoudre et corroder le calcaire et de créer des cavités. Le système des thermes de Santa Cesarea est composé de quatre cavités: Fetida, Sulfurea, Gattula, et Solfatara. Les morphologies hypogènes et les dépôts abondant de soufre natif (spécialement dans la cavité de Gattulla) et de minéraux sulfatés sont présents dans ces cavités. Les cavités de Fetida et Gattulla ont été étudiées en premier car elles sont facilement accessibles tout au long de l’année via des entrées artificielles, les autres cavités étant accessibles seulement depuis la mer. L’analyse géochimique de l’eau, le suivi de l’atmosphère des cavités, et la mesure des isotopes stables de S, O, et H ont permis d’identifier les principaux processus qui prennent place dans ce système complexe de cavités. En particulier, les variations de concentration en Ba2+ et Sr2+ ont permis d’identifier deux principaux domaines d’influence, caractérisés par des eaux marines et des eaux acides ascendantes.

Resumen

En este trabajo se describen las características geoquímicas e hidrogeológicas de Santa Cesarea Terme, un sistema espeleogenético activo basado en el ácido sulfúrico situado a lo largo de la costa adriática (Apulia, Italia meridional). Representa un sitio muy peculiar, donde las aguas termales y ácidas ascendentes se mezclan con el agua de mar creando soluciones subsaturadas con respecto al CaCO3, capaces de disolver y corrosionar la caliza y generar cuevas. El sistema de Santa Cesarea Terme está compuesto por cuatro cuevas: Fétida, Sulfurea, Gattulla y Solfatara. En estas cuevas hay morfologías hipogénicas y abundantes depósitos de azufre nativo (especialmente en la Cueva Gattulla) y minerales de sulfato. Las cuevas de Fétida y Gattulla se investigaron principalmente porque son fácilmente accesibles durante todo el año a través de entradas artificiales, mientras que las otras cuevas sólo son accesibles desde el mar. El análisis geoquímico del agua, la observación de la atmósfera en las cuevas y la medición de los isótopos estables de S, O y H ayudaron a identificar los principales procesos que se producen en este complejo sistema de cuevas. En particular, los cambios en la concentración de Ba2+ y Sr2+ permitieron identificar dos dominios principales de influencia, caracterizados por aguas marinas y aguas ácidas ascendentes.

摘要

这项工作描述了Santa Cesarea Terme的地球化学和水文地质特征,该处位于Adriatic海岸线(意大利南部Apulia)上的活跃的硫酸造山系统。它代表了一个非常奇特的场所,在这里,不断上升的热水和酸性水与海水混合,产生了CaCO3不饱和的溶液,能够溶解和腐蚀石灰石并形成洞穴。Santa Cesarea Terme系统由四个洞穴组成:Fetida,Sulfurea,Gattulla和Solfatara。这些洞穴存在表观形态和天然硫(尤其是在Gattulla洞穴中)和硫酸盐矿物的大量沉积物。对Fetida和Gattulla洞穴进行了调查,主要是因为它们整年容易通过人工入口进入,而其他洞穴只能从海上进入。对水进行地球化学分析,监测洞穴环境以及测量S,O和H的稳定同位素有助于确定该复杂洞穴系统中发生的主要过程。特别是,Ba2+和Sr2+浓度的变化可以确定两个主要的影响域,其特征是海水和上升的酸性水域。

Riassunto

Il presente lavoro descrive le caratteristiche geochimiche ed. idrogeologiche di Santa Cesarea Terme, un attivo sistema speleogenetico sulfureo ubicato lungo la costa Adriatica (Puglia, Italia meridionale). Esso rappresenta un sito molto interessante, dove le acque risalienti, termali e acide, si mescolano con l’acqua marina, producendo soluzioni sottosature rispetto al CaCO3, e capaci quindi di dissolvere e corrodere la roccia carbonatica creando vere e proprie grotte. Il sistema di Santa Cesarea Terme è composto da quattro grotte: Fetida, Sulfurea, Gattulla e Solfatara. Morfologie ipogeniche e abbondanti depositi di zolfo elementare (specialmente in Grotta Gattulla) e gesso sono presenti all’interno delle cavità. Le grotte Fetida e Gattulla sono state oggetto di dettagliati studi, essenzialmente grazie alla loro accessibilità durante tutto l’anno attraverso ingressi artificiali, mentre le altre cavità sono raggiungibili solo da mare. Le analisi geochimiche delle acque, il monitoraggio dell’atmosfera di grotta, e le misure degli isotopi stabili di S, O e H hanno consentito di identificare i processi principali che avvengono in questo complesso sistema di grotte. In particolare, variazioni nella concentrazione di Ba2+ and Sr2+ hanno consentito di discriminare i due principali domini di influenza, rappresentati da acque marine e da acque di risalita acide.

Resumo

Este trabalho descreve as características geoquímicas e hidrogeológicas da Terma de Santa Cesarea, um sistema espeleogenético de ácido sulfúrico ativo localizado ao longo da costa do Adriático (Apúlia, sul da Itália). Representa um local muito peculiar, onde as águas termais e ácidas ascendentes se misturam com a água do mar criando soluções subsaturadas em relação ao CaCO3, capazes de dissolver e corroer calcário e criar cavernas. O sistema da Terma de Santa Cesarea é composto por quatro cavernas: Fetida, Sulfurea, Gattulla e Solfatara. Morfologias hipogênicas e depósitos abundantes de enxofre nativo (especialmente na Caverna Gattulla) e minerais de sulfato estão presentes nessas cavernas. As cavernas Fetida e Gattulla foram investigadas principalmente porque são facilmente acessíveis durante todo o ano através de entradas artificiais, sendo as outras cavernas acessíveis apenas pelo mar. A análise geoquímica da água, o monitoramento da atmosfera da caverna e a medição dos isótopos estáveis de S, O e H ajudaram a identificar os principais processos que ocorrem neste complexo sistema de cavernas. Em particular, as mudanças na concentração de Ba2+ e Sr2+ permitiram a identificação de dois domínios principais de influência, caracterizados por águas marinhas e águas ácidas ascendentes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sulfuric acid speleogenetic (SAS) systems are hypogene caves (i.e., influenced by rising acidic waters) and, in contrast to epigene caves (i.e., formed by infiltrating waters), they typically are less involved in surface processes. Hypogene speleogenesis from a hydrogeological standpoint has been defined as “the formation of solutional-enlarged permeability structure (void-conduit systems) by fluids that recharge the cavernous zone from below, driven by hydrostatic pressure or other sources of energy, independent of direct recharge from the overlying or immediately adjacent surface” (Klimchouk 2017, p. 3).

Hypogene caves often develop along deep-rooted fractures and faults rather than bedding planes, and, being influenced by rising acidic waters and/or vapors passing through feeders (i.e. vertical and often narrow passages), produce morphologies such as cupolas, megacusps, blind chimneys, and domes (Audra et al. 2009; De Waele et al. 2016; D’Angeli et al. 2019a).

The most important reaction in SAS systems is the oxidation of H2S into H2SO4 (Egemeier 1981), a strong acid which rapidly reacts with the carbonate (CaCO3) host rock, producing gypsum by-products and releasing CO2 into the atmosphere, which, in turn, further amplifies the carbonate dissolution.

Sulfuric acid speleogenetic caves are widespread all over the world (Galdenzi and Menichetti 1995; Hose and Pisarowicz 1999; Hill 2000; Jagnow et al. 2000; Summers Engel et al. 2004; Galdenzi et al. 2010; Klimchouk 2017), and are widely documented in Italy (De Waele et al. 2014), hosting at least 25% of the known worldwide systems in 12 regions located along the Apennine Mountain Chain, in Apulia, and in the main islands of Sicily and Sardinia (D’Angeli et al. 2019a).

Nevertheless, actively forming SAS caves, only sporadically documented worldwide (Egemeier 1981; Sarbu and Lascu 1997; Hose et al. 2000; Galdenzi 2001; Macalady et al. 2006; Onac et al. 2009; Parise et al. 2015), have shown a wide range of temperatures. As a matter of fact, temperatures of 13–17 °C have been observed in Frasassi streams, Italy (Galdenzi 2001; Zerkle et al. 2016), 16–19 °C in Melissotrypa Cave in Greece (Popa et al. 2019) and in Mexico (Hose et al. 2000), ~29 °C in Ninfe Cave, southern Italy (Vespasiano et al. 2016; Galdenzi and Maruoka 2019), 29–37 °C in Acquasanta Terme in central Italy (Galdenzi 2001), and up to 53 °C in Diana Cave, Romania (Povara et al. 2008; Onac et al. 2013). The pH of fluids involved in SAS, due to the buffering effect of the carbonates, is commonly neutral and ranges between 6.5 and 7.4. H2S-rich fluids generally show a milky color due to suspended elemental sulfur (Hose et al. 2000), and geochemically can be classified as Na-Cl-SO4 and/or Ca-Cl-SO4 waters (Jones et al. 2015; Santaloia et al. 2016; Vespasiano et al. 2016).

The spatial and temporal concentration of H2S varies in both the cave water and atmosphere. In fact, at the same sample site, the variation of H2S concentration ranged between 17 and 750 ppm in Cueva de Villa Luz in Mexico (Hose et al. 2000), and from <0.1 to 20.5 ppm in the Frasassi caves (Jones et al. 2015). Along with H2S, also CO2 and CH4 are present in the rising fluids and intervene in some SAS reactions. As a matter of fact, rising fluids enriched in hypogene CH4 and CO2 may contribute to increase the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, which is a further reason to study the CH4, CO2 and H2S content in active SAS caves. Geological carbon sources may complicate the mass-balance measurement of the Earth’s carbon cycle (Rye et al. 2012), with SAS caves behaving as methane producers, in contrast to epigene caves which are methane sinks (Fernández-Cortès et al. 2015).

Important information regarding both H2S sources and reactions involved in the sulfur cycle (Eckardt 2001; Canfield 2001) can be inferred by sulfur stable isotopes.

The isotopic composition for sulfur is expressed in δ34S (‰) according to the following equation:

δ34S is normalized to the Vienna Cañon Diablo Troilite (VCDT) standard, and the average δ34S values vary from −50 to +35‰. One of the most striking chemical signatures of SAS is the depletion in the heavier isotope (δ34S down to −25‰) in secondary gypsum ascribed to the bacterial sulfate reduction (BSR) or dissimilatory sulfate reduction (DSR).

Studies on δ34S fractionation during sulfur oxidation have shown that the δ34S shift can be very small, producing no fractionation at high temperature (Ohmoto and Rye 1979) and small fractionation at low temperature (Fry et al. 1988). Nevertheless, in the Cerna Valley of southwest Romania, the wide range of δ34S values derive from thermal sulfate reduction (TSR) of sedimentary sulfates; the reaction of sedimentary sulfates with methane, produced by bacterial decay of nearby coal deposits, is very significant (Onac et al. 2011). These reactions are limited by methane and/or sulfate during reduction, and by oxygen during oxidation.

In contrast, sulfate-reducing bacteria are able to produce 34S-depleted H2S (Strauss 1997). BSR causes δ34S values to shift by as much as −30‰, and sulfides resulting from this process have an average δ34S value of −12‰ (Seal 2006). DSR can produce sulfides depleted in 34S by more than −40‰ (Zerkle et al. 2016). The biological disproportion of intermediate compounds, such as thiosulfate (S2O32−), sulfite (SO32−), and elemental sulfur (S0), can induce large isotopic differences, with H2S depleted in 34S (+5 to +7‰) with respect to SO42− (+17 to +21‰) (Canfield and Thamdrup 1994). Furthermore, the shift of stable oxygen and hydrogen isotopes (δ18O and δ2H), normalized using the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW), from the Global Meteoric Water Line (GMWL; D’Amore and Panichi 1987) for groundwater, can help to identify meteoric sources, fluid–rock interactions along flow paths and temperature gradients, including low/high temperature mineral reactions, CO2 exchange, hydration of silicates, and H2S exchange (Karolytė et al. 2017; Craig 1961).

Rainfall values of the GMWL in central Italy have been documented to range between −9.02 and −4.18‰ for δ18O and between −58.8 and −19.8‰ for δ2H (Bono et al. 2005), whereas for the Apulia area, Longinelli and Selmi (2003) reported values ranging from −5.31 to −4.91‰ for δ18O, and from −32.0 to −29.1 for δ2H, at the towns of Ceglie Messapica, San Giorgio Ionico, and Santa Maria di Leuca.

In addition, the study of trace and rare earth element (REE) contents provides information on the origin and sources of rising fluids (D’Amore et al. 2005)—for example, Sr and Ba are released by rock and soil weathering (Greve et al. 2007), Mn, Fe and Al derived from Fe-bearing alumino-silicates dissolution, and Fe, Ni, Cu and Zn can testify to the presence of living systems (Ali Khan et al. 2010). REE concentration in deep-sea hydrothermal environments is generally 10–103 times higher than in seawater (Wang et al. 2013), and a study of the shells of benthic animals living close to hydrothermal springs helped in recognizing the source and evolution of fluids (Zeng et al. 2018).

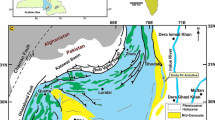

The aim of this work is to describe the hydrogeological characteristics and the baseline geochemistry in the Santa Cesarea Terme (SCT) karst groundwater system (southeastern area of Apulia foreland), consisting of four SAS caves—namely Fetida, Sulfurea, Gattulla, and Solfatara (or Sulfurara; D’Angeli et al. 2017)—which open along the Adriatic coastline at present sea level (Fig. 1). At SCT, the groundwater flows with piezometric gradient of about 0.03% toward the Adriatic coast, where it emerges in several locations, including the four caves along the coastline. Maximum specific discharge measured in boreholes inland is over 100 L/s/m, and is likely related to a higher level of karstification along the main discontinuity systems (Ciardo 2006).

a Map showing the location of the Santa Cesarea Terme karst system in Italy and the piezometric contours (grey lines, depth in m) in the Salento region. The grey dots show the location of cities and towns. The enlargement (b) displays the location of Fetida (PU 102), Sulfurea (PU 103), Gattulla (PU 105), and Solfatara (PU 914) caves. The sites of water sampling in Fetida Cave (SCA1, SCAfin, SCB1, SCC1), Gattulla Cave (SCG1) and the Adriatic Sea (M1) are shown as colored dots. PU refers to the regional code in the register of natural caves of Apulia. c Two geological cross-sections (A–A′ and B–B′), modified after Cotecchia (2014). Country codes according to ISO (2020)

Geological setting

Apulia (in the extreme southeastern portion of Italy) represents a foreland basin for the southern Apennine and Dinarides orogens (Ricchetti 1980; Ricchetti et al. 1988). Here, the Hercynian crystalline basement (Pieri et al. 1997) with a felsic composition is overlain by Meso-Cenozoic sedimentary rocks (thickness of 4–12 km) and thin Plio-Pleistocene carbonates (Tropeano et al. 2004). Two important tectonic features (the Ofanto Graben and Soglia Messapica) divide the Apulian foreland into main blocks, corresponding to three karst regions (Funiciello et al. 1991; Parise 2011): Gargano (to the north), Murge (central Apulia), and Salento (to the south). Normal faults have been recorded in all the blocks with variable ages (Mesozoic-Pleistocene) associated with Apennine (NW–SE) and anti-Apennine (NE–SW) stress fields (Tadolini and Bruno 1993; Gambini and Tozzi 1996).

The Salento peninsula of southern Apulia is a carbonate plateau defined by a wide, WNW–ESE trending, antiform structure, dissected by normal and strike-slip faults (Tozzi et al. 1988), and characterized by shallow-water carbonate sedimentation (Mostardini and Merlini 1986). Since the Cretaceous, the Salento platform experienced multiple phases of transgression and regression that produced an overall stratigraphic succession characterized by several unconformities (Doglioni et al. 1994).

Quaternary tectonics characterize Salento terrains, with Pleistocene deposits cut by several normal faults (Martinis 1962; Moretti 1996). A model of the Apulian crust, reconstructed to identify potential detachment faults and the role of the Apennine orogeny, showed that the Moho depth in the Apulia foreland ranges between 26 and 31 km, with thickness of the Meso-Cenozoic platform increasing from Gargano (4–6 km) in the north to Salento (11 km) in the south (Amato et al. 2014). Given the widespread outcrop of carbonates, Salento terrains are extremely rich in karst landforms, with development and spatial distribution strongly controlled by tectonics, as shown by research at the surface and within cave systems (Onorato et al. 1999; Denitto et al. 2006; Festa et al. 2012; Pepe and Parise 2014). Hundreds of caves characterize both the Adriatic and Ionian coastlines of Salento, creating one of the main attractions for tourists in the area. Furthermore, the low-lying topography, with flat beaches approaching the seas, is frequently affected by sinkhole development, due to the rapid evolution of caves from the mixing of brackish and freshwater along the coasts (Delle Rose and Parise 2002; Delle Rose and Leucci 2010; Del Prete et al. 2010; Margiotta and Parise 2019).

The SCT area is located along the coast of SE Salento (Fig. 1). Here the Upper Cretaceous micritic Altamura Limestone Formation is overlain by the Eocene-Oligocene coral reef Castro Limestone Formation (Bosellini et al. 1999; Bossio et al. 2008). Both limestones are locally, in turn, unconformably overlain by the Oligocene Porto Badisco Calcarenites and the Messinian Andrano Calcarenites. Eventually, Plio-Pleistocene formations crop out, consisting of the yellow calcarenites of Uggiano La Chiesa Formation and the massive to poorly bedded and weakly cemented Salento Calcarenites. The whole carbonate succession is unconformably covered by terra rossa and talus deposits. Terra rossa may reach significant thickness (up to 4–5 m) in large topographic depressions.

Karst landforms appear to be structurally controlled in the study area, with the NW–SE fault systems playing a dominant role, as also observed in other sectors of Salento (Pepe and Parise 2014). Several normal and trans-tensional structures characterize the SCT area, mostly represented by NW–SE faults with related pull-apart features, and subordinate presence of SW–NE and N–S faults.

From a hydrogeological standpoint, the SCT area behaves as most of the Salento peninsula, a karst region with average rainfall between 500 and 800 mm/year. The surface runoff is typically limited to the occurrence of the most extreme and rapid rainfall events, or to the immediate aftermath of long-lasting moderate rains. Rainwater infiltrates immediately into the subsoil in a diffuse way, or through the numerous dolines and swallow holes. Both types of contributions provide natural recharge to groundwater. There is a high degree of difficulty in delineating the boundaries of single catchments (Gunn 2007) and in evaluating the different components of the recharge, due to the prevailing flow through karst conduits. Therefore, due to widespread karst phenomena, at the surface and at depth, most of the geological formations are mainly characterized by secondary permeability, related to the presence of several structural discontinuities, with multi-stage development of karst processes. Interaction with marine water has to be taken into account also, with the peculiar lenticular shape characterizing the fluctuating fresh/salt-water interface.

In the hydrogeological map in Fig. 2, the geological formations have been merged on the basis of the role they play in the groundwater circulation, and also on the similarity in their hydrogeological characteristics and permeability values. Three main hydrogeological units have been thus recognized: the Pliocene-Pleistocene calcarenites, with medium permeability which is a function of grain size and litho-stratigraphic conditions, with hydraulic conductivity values of about 10–5 m/s (Andriani and Walsh 2010); the Miocene calcarenites, with very low porosity, and permeability linked essentially to fracturing, leading to lower values of hydraulic conductivity (10−6 m/s); and, finally, the set of Cretaceous-Paleogene limestones, characterized by fracturing and intense karst processes, with high permeability values (10−3 m/s hydraulic conductivity; Cotecchia 2014, and references therein).

a Schematic profile and b hydrogeological map at Santa Cesarea Terme. The lithologies have been grouped into hydrogeological units, consisting of the mainly porous Plio-Pleistocene calcarenites, resting on the Miocene calcarenites, these latter unconformably covering the bedrock, permeable due to karstification and fracturing. The piezometric contour lines are supplied by the Water Safeguard Plan by Apulia Region (Regione Puglia 2008). The profile C–C′ shows water upwelling from the main faults. The thicknesses of the hydrogeological units in the profile are not to scale

Notwithstanding the small groundwater flow gradient, a groundwater flow toward the sea is present (Fig. 2), as is common along most of the Apulian coastlines, where the groundwater flow is drained at many submarine springs. The presence of these springs was ascertained by infrared thermal surveys (Cotecchia 2014, and references therein), but their discharge is difficult to evaluate quantitatively, with the exception of the most significant ones (Liso and Parise 2020).

Several faults have been recognized in the area, both along the shoreline and inland (Vigor 2014). Regarding their age, in the sectors where Plio-Pleistocene deposits crop out, some of these faults cross them, thus testifying to the fact that tectonic activity was not limited to post-Miocene time.

The village of Santa Cesarea Terme is located on a structural high of the Altamura and Castro Limestone formations, bounded by NW–SE structures that may be followed offshore (Zuffianò et al. 2013). The importance of the NW–SE fault system is further shown by the control it exerts on the spatial development of the four caves, and the presence of the thermal springs therein.

The emergence of deep upwelling water at the sea surface is visible as white plumes during quiescent marine conditions and winds. In the caves, degassing H2S from rising thermal waters is rapidly oxidized into H2SO4 in condensation waters on the cave walls and ceilings, reacting with the host carbonate and replacing calcite with gypsum (D’Angeli et al. 2018). Dissolution rate monitoring in the innermost portion of Fetida Cave (SCB1 and SCC1 in Fig. 1) is still ongoing, but the first results showed that dissolution-corrosion is greater at the water–air interface than in subaqueous and aerated conditions (D’Angeli et al. 2019c).

Several hypotheses have been presented for the origin of the sulfidic springs. In one scenario, elevated temperatures, several degrees higher than in shallow groundwater, are due to exothermic reactions of sulfate in the seawater interacting with organic matter in the Miocene calcarenites (Zezza 1980; Calò et al. 1983; Calò and Tinelli 1995). According to researchers, thermal waters could derive from connate fluids, confined at depth and associated with hydrocarbons in the Otranto Channel, rising along fault systems in the Dinaric foredeep bedrock, with elevated temperatures due to the regional geothermal gradient (Maggiore and Pagliarulo 2003).

For reference, sulfur-rich thermal water in the Salento karst region is not limited only to the SCT area, since it has been identified at other sites such as the Ionian coast near Ugento, where a borehole intersected sulfur-rich water below a thick layer of lower Pleistocene clays (Calò and Tinelli 2004).

The four SAS caves (Fig. 1) in SCT are developed along a 500-m-long stretch of the Adriatic coastline (Fig. 3) in the micritic and fossiliferous Altamura Limestone Formation (D’Angeli et al. 2017, 2019b; Olarinoye et al. 2020; Liso and Parise 2020).

The thermal properties of these caves have been known and described by scholars since the nineteenth century (Mauget 1875; De Giorgi 1882, 1901, 1922), and three have been used as spas since the 1930s (Corti 1992). These caves are a significant tourist attraction and economic resource in Apulia. All four caves are relatively short (30–588 m), low and wide, developed at modern sea level (maximum depth of 17 m in Fetida Cave; Table 1), and follow NW–SE discontinuities.

Methods

The hydrogeological units have been defined based upon the stratigraphic data from the official geological maps, integrated by the outcomes of the Vigor Project (Vigor 2014).

The piezometric contours at Salento, and in the SCT area as well, were reconstructed from a variety of sources, starting from the Water Safeguard Plan of Apulia Region, updated after Cotecchia (2014) and the Vigor Project. All sources used thousands of wells, where the water level measurements were carried out using a piezometric probe with centimeter accuracy. At SCT, for the detail shown in Fig. 2, more than 200 wells (Irrigation Authority of Apulia and Basilicata, Consorzio di Bonifica Ugento Li Foggi, private wells, etc.) were surveyed. The topographic elevations, to which the depths of the piezometric level were referred, were obtained from the Technical Regional Topographic Maps (scale 1: 5000).

Geochemical analyses of water and monitoring of the cave atmosphere were performed at Gattulla and Fetida caves, the only ones of the SCT karst system that are easily accessible during the whole year.

From October 2015 to November 2018, 27 waters samples were collected from four sample sites in Fetida Cave (SCA1, SCAfen, SCB1, SCC1), 7 from Gattulla Cave (SCG1), and four samples in the Adriatic Sea (M1)—Fig. 1, Table 2, Table S1 of the electronic supplementary material (ESM). At the sample sites close to the entrance of Fetida Cave (SCA1 and SCAfen), because of a storm and adverse conditions, it was impossible to collect samples on March 7, 2016. Water parameters such as pH, temperature (T), electrical conductivity (EC), and total dissolved solids (TDS) were measured using a Hanna HI991001 portable probe at the time of sampling (relative accuracies at 25 °C: ±0.02 pH, ±0.5 °C, ± 2% EC/TDS). Water samples were collected in 250-ml HDPE bottles, one acidified with 65% HNO3 for cations, and stored at 4 °C. The concentration of dissolved HS− was measured in situ using a Hach DR/2010 spectrophotometer. Geochemical analyses were performed at Politecnico of Torino University: cations were analyzed using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer Thermo S (AAS), anions with ion chromatography, NH+ by colorimetry, and alkalinity (HCO3−) through titration with HCl and methylorange as indicator. Saturation indices (SI) for calcite, dolomite and gypsum were calculated using the Debye-Hückel Eq. (SI = 0 equilibrium condition, SI < 0 undersaturation, SI > 0 oversaturation).

Gas monitoring was done during fieldwork on June 8, 2017, and on May 7, 2018, using a portable MSA Altair 4X multigas detector able to measure O2 (0–30 ± 0.7 vol%), SO2 (0–20 ± 1 ppm SO2), H2S (0–200 ± 2 ppm), and temperature (−20 to 60 ± 0.5 °C).

Two samples of water in Gattulla Cave (at SCG1 and at the natural entrance) were collected for sulfate δ34S analysis on December 10, 2016, using 1-L HDPE containers. Samples were acidified by adding 10 ml of a 0.25 M BaCl2 solution to precipitate BaSO4, and the resulting powders were collected in Eppendorf tubes and analyzed at the ETH Zurich, Switzerland. The precipitates were wrapped in tin capsules with V2O5 and converted into SO2 in a Thermo Fisher Flash-A 1112 analyzer coupled with a ConFlo IV, interfaced to a Thermo Scientific Fisher Delta V isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS). Isotope ratios are reported in the conventional δ-notation with respect to VCDT. The method was calibrated with the reference materials NBS-127 (δ34S = +21.1‰), IAEA-SO-5 (δ34S = +0.5‰) and IAEA-SO-6 (δ34S = −34.1‰). Measurement reproducibility based on the repeated analysis of an internal standard was better than 0.3‰.

During the same field campaign in December 2016, waters in Gattulla (SCG1) and Fetida caves (SCAfen, SCC1), and waters from ceilings in Fetida Cave (SCAfin, SCC1) were sampled in 2-ml borosilicate vials to study δ2H and δ18O. These samples were analyzed at the Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis water isotope laboratory using a Picarro L2130-i analyzer coupled to an auto sampler and high-precision water vaporizer unit. Measurements were corrected for memory and drift following the methodology of Geldern and Barth (2012). Final values were corrected to the VSMOW scale using calibrated standards from Los Gatos Research. Precision for δ18O and δ2H was 0.1 and 0.6‰, respectively. In Table 2 all the sampling and monitoring campaigns carried out in Gattulla, Fetida and water collection of Adriatic Sea are summarized.

Results

Ion concentrations for all the six sample sites are reported in Table S1 of the ESM and show charge balances lower than 1.09% for all sites. The geochemistry of both sea and cave samples belongs to the Na-Cl-SO4 type of waters (Fig. 4).

Ludwig-Langelier diagram for waters. All samples from the sea and caves are located within the Na-Cl-SO4 field. Sample sites are shown in Fig. 1

Seawater (M1) presents the highest pH, [Na+], [K+], [Mg2+], [Cl−], [SO42−], TDS, and the lowest [Ca2+] and T (from seasonal variation). SCB1, a discrete spring of rising thermal water, shows the highest T, [HS−], [Ca2+], and the lowest pH (Fig. 5a, b).

In the innermost zone of Fetida Cave (SCC1 and SCB1) temperatures higher than those close to the entrance (SCA1, SCAfen) are observed, and particularly in SCB1 where a clear site of rising sulfur-rich water was found that reached 29.1 °C in December 2016. Nevertheless, the whole system is influenced by the sea; in March 2016, during a storm, temperatures of 14.6 (SCB1) and 15.3 °C (SCC1) were recorded.

In Gattulla Cave (SCG1) temperatures range between 15.3 and 25.4 °C and are slightly higher than seawater (M1) which vary from 15.7 to 21.1 °C (Table S1 of the ESM).

Trace elements (Fig. 5c–d; Table 4) such as Cu and V, are more abundant in seawater (M1), whereas Ba, Sr and Zn concentrations are higher in the innermost portion (SCB1 and SCC1) of Fetida Cave. SCG1 in Gattulla Cave shows the highest concentration of rare earth elements (Fig. 5e, f; Table S2 of the ESM) such as Y, Er and Yb, whilst in the innermost portion (SCC1) of Fetida Cave, La, Nd and Eu are more abundant.

a Mean values of major and minor element abundances; b Close-up view of a on a different scale; c Mean values of trace element abundances; d Close-up view of c on a different scale; e Mean values of REE abundances; f Close-up view of e on a different scale. The values of the analytical standard (black-dashed line) are reported on the primary (left) y axis (c–f). The standards are from Taylor and McLennan (1985)

Saturation indices (denoted C-SI for calcite, D-SI for dolomite, and G-SI for gypsum) at the sample sites (Fig. 6) showed that waters are mostly oversaturated with respect to calcite and dolomite, and undersaturated with respect to gypsum during the whole monitoring period (October 2015 to November 2018). Only sample sites SCAfen, SCB1, and SCC1 showed some samples to be undersaturated and/or close to the equilibrium line with calcite. In addition, in the two caves, some samples were slightly oversaturated or at equilibrium with gypsum. Calcite (C-SI) and dolomite (D-SI) saturation indices exhibit a clear correlation, whereas both gypsum (G-SI) versus calcite (C-SI) and gypsum (G-SI) versus dolomite (D-SI) do not appear to be correlated.

a–f Calcite (C-SI), gypsum (G-SI), and dolomite (D-SI) saturation indices for all the sample sites. The horizontal black dashed line indicates the equilibrium condition. All values above the line are oversaturated, whilst those below are undersaturated. Graphs (g–i) display the correlation between saturation indices. Calcite and dolomite are well correlated, whereas both calcite-gypsum and dolomite-gypsum are not correlated

The sample collected for δ34S (December 10, 2016) at the entrance of Gattulla Cave returned values in the range of marine water, whereas in its innermost zone the values are more depleted in the heavier isotope (Table 3). For δ18O and δ2H, cave waters returned values similar to ocean water. Waters from ceilings in Fetida Cave are more depleted in the heavier isotope (Table 3).

The minimum, maximum, median and standard deviation values of O2, H2S, SO2 concentration in the cave air during the fieldwork in June 2017 and May 2018 both in Gattulla and Fetida caves are reported in Table 4. Oxygen concentrations are at standard atmospheric values (20.8%). The concentration of H2S was quite variable at all sites during the monitoring time. The highest concentration of H2S was observed at SCB1 (15.40 ppm lasting for 30 s). The recorded temperature was always above 23 °C.

Discussion

The rising groundwater in the caves of SCT shows a mean temperature of 23 °C, 7 C° higher than the local average annual air temperature. Since Schoeller (1962) and White (1969) suggested that a mean groundwater temperature of at least 4–5 °C higher than the regional annual mean may be considered slightly thermal, and Ford (1995) identified groundwaters elevated by 20 C° above the mean as a threshold for hydrothermal environments, the SCT cave system can be considered slightly thermal. Santaloia et al. (2016) describe SCT as a peculiar low-temperature geothermal system, located in a zone of low heat flux and great lithospheric and crustal thickness (120 and 45 km, respectively).

In general, the SCT system is influenced both by rising sulfidic fluids and seawaters, which tend to mix. Seasonal effects, modest water head variations (i.e. tides), and meteo-marine conditions (smooth, rough, long-term rough water) strongly affect the SCT caves, causing geochemical variations, in particular at the cave entrances.

The innermost portion of Fetida Cave (in SCB1 and SCC1) is dominated by rising sulfidic waters where temperatures and pH can reach values of 29.0 °C and 6.76, respectively, whereas its entrance (SCA1) and Gattulla Cave (SCG1) are controlled by mixing of rising sulfidic fluids and seawaters producing temperatures and pH ranging from 15.3 to 26.50 °C, and from 7.01 to 8.16, respectively.

Air temperature in the innermost portion of Fetida Cave is more stable with respect to the entrance of Fetida (SCA1) and Gattulla Caves (SCG1), which are more influenced by outside variations. However, the H2S concentrations recorded in the atmosphere and water of SCA1 and SCG1 suggest that sulfidic rising fluids characterize the underground environment of SCT. Sulfide-rich waters show a milky appearance (Hose et al. 2000; Macalady et al. 2006; D’Angeli et al. 2017) and, when conditions are favorable, they are visible as white plumes along the coastline.

Based on these results, the waters collected inside the caves (SCA1, SCAfen, SCB1, SCC1, SCG1) and along the coastline (M1) can be classified as Na-Cl-SO4 waters (Fig. 4), with detailed geochemical composition (major and minor, trace and rare earth elements) reported in Tables S1 and S2 of the ESM. Saturation indices (Fig. 6) for calcite (C-SI), dolomite (D-SI) and gypsum (G-SI) showed these waters to be undersaturated with respect to gypsum, slightly oversaturated with calcite and oversaturated with dolomite. Only a few samples from SCB1 and SCAfen are at the equilibrium condition for calcite, whereas in SCC1 some are slightly undersaturated with respect to calcite.

The concentration of [HS−] is quite variable over time and seems to be linked to episodic activities, as documented in Cueva de Villa Luz (Hose et al. 2000) and in Frasassi caves (Jones et al. 2015). Indeed, in SCT it was observed that the H2S concentration can suddenly change both in water and air (Table S1 of the ESM and Table 4).

In the water, [HS−] tends to increase with higher temperatures and lower pH, both associated with warmer sulfidic inputs in the system (Fig. 7). The correlation between temperature and [HS−] is a bit stronger (R2 = 0.46) than that related to decreasing pH (R2 = 0.36).

a The relation between [HS−] (ppm) content and temperature (°C), showing that warmer waters contain higher concentrations of [HS−]. b The relation between [HS−] (ppm) content and pH, showing that more acidic waters contain higher concentrations of [HS−]. [HS−] content shows a higher correlation with the increase of temperature rather than with the decrease in pH

Moving from the innermost portion of Fetida Cave towards the Adriatic Sea, a general increase of water salinity (Na+, Cl−, and TDS; Fig. 8a) was observed. [Mg2+] and [Ca2+] show an opposite trend, likely related to different processes ([Mg2+] is more influenced by seawater). [SO42−] and [HCO3−] have an opposite trend too, whereas [Ca2+] and [HS−] exhibit a similar behavior (Fig. 8b). This would indicate [Ca2+] in solution linked to an increase of [HS−]. [HS−] inputs from rising acidic fluids would also change the pH and temperature. Moving from the innermost portion of Fetida Cave towards the sea, pH tends to increase whilst T and [HS−] decrease. Trace elements such as Sr and Ba, as shown in Fig. 9, are more abundant in the innermost portion of Fetida than in the seawater. It is well known that [Sr2+] and [Ba2+] can substitute [Ca2+] ions (Lucas et al. 1990; Gabitov et al. 2013), and thus, the further dissolution-corrosion of carbonate host rock induced by rising acidic waters (D’Angeli et al. 2018) in contact with deep-seated Ca-sulfates, would increase their concentration in solution. In contrast, V and especially Cu ions, which show a constant concentration inside the cave, tend to increase in seawater. Cu is essential for marine biogeochemical processes such as photosynthesis, respiration, N-cycling and Fe-assimilation. Actually, a low concentration of free Cu (lower than 10−11 ppm) can limit phytoplankton production (Maldonado et al. 2006; Thompson 2015).

Graphs displaying the tendency of major and minor elements and chemical–physical parameters (TDS, T, pH) moving from the innermost portion of Fetida toward the entrance and the Adriatic Sea; a Mean values of Na+, Cl−, TDS (on the primary y axis), Mg2+, Ca2+, SO42−, HCO3− (on the secondary y axis); b Mean values of HCO3−, HS− (on the primary y axis), Ca2+, SO42− (on the secondary y axis); c Mean values of pH, HS− (on the primary y axis), temperature (on the secondary y axis). The dashed line is for the elements on the secondary y axis

Na+ and Cl− are well correlated (R2 = 0.95497) as shown in Fig. 10a. As expected, [HS−] has an influence on [Ca2+] (Fig. 10c), but not on [Na+]/[Cl−] (Fig. 10b). Figure 10d–f document a clear two-field distribution of the [Ba2+]/[Sr2+] ratio corresponding to: (1) rising acidic fluids; and (2) marine waters. The samples collected in the Adriatic Sea are always in the domain of marine influence, whilst all the other sample sites, from both Gattulla and Fetida caves, depending on sampling conditions, can fall in both the domains. These distributions would testify that, even if strongly dominated by rising acidic waters, the innermost portion of Fetida Cave is still subjected to marine influence.

a The correlation between Na+ and Cl−, which is close to 95%; b The concentration of Na/Cl, which is shown not to be influenced by the increase of HS−; c The concentration of Ca2+, as influenced by HS−. d–f The Ba2+/Sr2+ ratio, compared with Mg2+, Ca2+/HCO3−, and Ca2+ /SO42−, respectively; in these three graphs it is possible to see two main domains: (1) rising acidic fluids; (2) marine. The legend is displayed in f

[Cl−] and [Br−] are conservative and highly soluble ions, and their ratio can be used as a natural tracer to understand the origin and evolution of groundwater (Freeman 2007; Alcalá and Custodio 2008), and also to elucidate the source of salinity in coastal aquifers (Alcalá and Custodio 2004). [F−] has been considered an important tracer both for seawaters and geothermal active areas (Edmund and Smedley 2013). Geothermal waters can constitute a source of natural fluorine contamination (Nordstrom and Jenne 1977).

In SCT, using [Cl−], [Br−], and [F−], unusual ratios were observed (Table 5). The Adriatic Sea water (M1) showed the highest [Cl−]/[Br−] and ([Cl−]/[Br−])/([Ca2+]/[Mg2+]), and the lowest [F−]/[Cl−] and [F−]/[Br−] ratios. The sample site in Gattulla Cave (SCG1) is more influenced by seawater fluctuation than those at Fetida Cave. All the sample sites in Fetida Cave are characterized by ratios influenced by the amount of rising acidic inputs mixing with seawater.

Almost all REEs show positive anomaly trends (Fig. 5e, f). As described by Lawrence and Kamber (2007), shale-normalized seawaters are characterized by various anomalies, with La as the most abundant element, followed by Y/Ho, Eu, Gd, and Lu. Since leaching of RREs La, Nd and Y increases with the consequent rise of acidity and temperature, the concentration of La, Nd and Y, shown in Fig. 5e, f, might be linked with rising sulfidic thermal fluids and sulfuric acid interaction (Kim et al. 2020).

Values of δ34S at the entrance in Gattulla Cave are close to modern Mediterranean seawater (+21‰; Böttcher et al. 1999), whereas waters sampled in the cave interior (SCG1) are more negative, likely due to BSR. Indeed, waters in both Gattulla and Fetida caves during calm seawater conditions exhibit abundant white floating and rock-attached filaments, which in Fetida Cave have been recently described by D’Angeli et al. (2019b) to be dominated by bacterial taxa involved in sulfur oxidation and reduction in aquatic, aphotic, microaerophilic/anoxic environments (Campylobacterales, Thiotrichales, Arenicellales, Desulfobacterales, Desulforomonadales).

Stable isotopes of O and H from Gattulla in SCG1 (1.19‰ for δ18O, and 7.79‰ for δ2H, respectively) are different from those observed in the waters of Fetida Cave (Table 3) collected at SCAfen (0.17‰ for δ18O and 1.85 for δ2H) and SCC1 (0.11 for δ18O and 1.96‰ for δ2H), which may indicate differences in recharge source inputs, water circulation, residence time, and/or degree of mixing between rising fluids and seawaters (Karolytė et al. 2017).

The waters from ceilings collected in two sample sites of Fetida Cave showed negative values −3.15‰ for δ18O and −3.50‰ for δ2H (SCC1) and −3.64 δ18O and −6.86 for δ2H (SCAfen), and plot above the GMWL in the area where H2S exchange might occur (Karolytė et al. 2017; Fig. 11). They likely derived from evaporation of rising sulfidic water mixed with seawater, which rapidly condensate on ceilings. The relative absence of stalactites, soda straws and stalagmites would testify to the limited amount of surface-water infiltration, as previously stated in the description of the hydrogeological setting. Nevertheless, further investigations on stable S isotope signatures will help to understand the source of H2S, thought to be associated with the reduction of sulfates contained in the seawaters (Zezza 1980) and/or Triassic deep-seated gypsum (Galdenzi and Menichetti 1995).

Graph displaying the Global Meteoric Water Line (GMWL) by Rozanski et al. (1993), who proposed the following equation: δ2H = 8.17δ18O + 11.27. The two samples from Fetida Cave are placed in the area dominated by H2S exchange

These results, together with previous works (Santaloia et al. 2016; Zuffianò et al. 2018), suggest the SCT coastal karst represents a localized geothermal anomaly, where moderately faulted zones, acting as the most relevant permeability sectors, alternate with less permeable areas.

As demonstrated by Calò and Tinelli (1995), rising sulfidic waters can reach the surface through deep tectonic fractures and karst flowpaths, generating bell-shaped upwelling of groundwater. Nevertheless, their behavior is extremely sensitive to both (1) modest water head variations (tidal fluctuations, increase of colder freshwater thickness), and (2) seawater conditions (smooth, rough, long-term rough water). Hydrogeological monitoring of thermal water flowpaths helped to assert the important influence of sulfidic fluids on the SCT karst system, especially during low and calm seawater conditions, showing evident zonation (Calò and Tinelli 1995). Rough sea conditions create different hydrodynamic situations (see Fig. 9 in Calò and Tinelli 1995), inducing the loss of water zonation, with more homogeneous values of temperature and salinity. The concentration of hydrogen sulfide is variable as a consequence of tides (Visintin 1945).

Conclusions

In Santa Cesarea Terme, rising sulfidic fluids mixing with seawater along the coastline produced a system composed of four small-sized caves—Fetida, Sulfurea, Gattulla, and Solfatara—formed along the main regional, NW–SE oriented, geological structures.

This study describes the hydrogeological and geochemical investigations performed during several field campaigns from October 2015 to November 2018. The hydrogeology of the system is complex, and still needs further efforts in order to reach substantial conclusions about the origin of the sulfur springs. The present state of knowledge can surely confirm the important influence of seawater movements on the local hydrogeology at SCT; this can significantly modify the elemental contents, temperature and pH of the overall solution. During a storm, in the sample sites where it was possible to collect samples, lower temperatures and higher values of pH were recorded, which are surely linked with seawater intrusion inside the caves.

Nevertheless, geochemical analysis showed the presence of a clear rising sulfidic fluid spot, recognized in the innermost portion of Fetida Cave and in particular at SCB1 sample site. δ34S results from water collected in Gattulla Cave showed values typical of modern Mediterranean seawater (+21‰) with a clear imprint of bacterial sulfate reduction (+15‰) likely induced by the sulfur-reducers found inside the white filaments coming towards the surface with rising waters. δ18O and δ2H of waters upwelling in Gattulla and Fetida caves may have differences in recharge source inputs, water circulation, residence time and/or degree of mixing between rising and seawaters (Karolytė et al. 2017), whilst those collected from ceilings in Fetida Cave exhibit values typical of H2S exchange, and would derive from the evaporation of rising sulfidic fluids mixed with seawater and their subsequence condensation on ceilings. The variable concentration of Ba2+ and Sr2+ in the same sample site over time allowed for identification of both marine and rising acidic domains. In addition, the higher concentrations of La, Nd, and Y with respect to the other REEs would testify to a significant influence of sulfuric acid in their mobilization. The lack of common epigene speleothems such as soda straws, stalactites, and stalagmites reflects the scarce surface seepage, thus indicating minimal contribution by freshwater in the dissolution. Santa Cesarea Terme, already classified as a sulfuric acid speleogenetic system (D’Angeli et al. 2019a), can be also considered a great example for the study of karst evolution due to the mixing of sea water and deep rising sulfidic waters.

References

Alcalá FJ, Custodio E (2004) Use of the Cl/Br ratio as tracer to identify the origin of salinity in some coastal aquifers of Spain, 18 SWM. IGME, Cartagena, Spain, pp 481–497

Alcalá FJ, Custodio E (2008) Using the cl/Br ratio as tracer to identify the origin of salinity in aquifers in Spain and Portugal. J Hydrol 359:189–207

Ali Khan MM, Umar R, Lateh H (2010) Study of trace elements in groundwater of Western Uttar Pradesh, India. Sci Res Essays 5(20):3175–3182

Amato A, Bianchi I, Piana Agostinetti N (2014) Apulian crust: top to bottom. J Geodynam 82:125–137

Andriani GF, Walsh N (2010) Petrophysical and mechanical properties of soft and porous building rocks used in Apulian monuments (south Italy). In: Prikryl R, Torok A (eds) Natural Stone Resources for Historical Monuments. Geol Soc Lond Spec Publ 333, pp 129–141

Audra P, Mocochain L, Bigot JY, Nobécourt JC (2009) Morphological indicators of speleogenesis: hypogenic speleogens. In: Klimchouk AB, Ford DC (eds) Hypogene speleogenesis and karst hydrogeology of artesian basins. Ukrainian Institute of Speleology and Karstology (Spec. paper 1), Simferopol, Ukraine, pp 17–22

Bono P, Gonfiantini R, Alessio M, Fiori C, D’Amelio L (2005) Stable isotopes (δ 18O and δ 2H) and tritium in precipitation: results and comparison with groundwater perched aquifer in central Italy. International Atomic Energy Agency-TECDOC-1453, IAEA, Vienna, pp 115–124

Bosellini A, Bosellini FR, Colalongo ML, Parente M, Russo A, Vescogni A (1999) Stratigraphic architecture of the Salento coast from capo d’Otranto to S. Maria di Leuca (Apulia, southern Italy). Riv Ital Paleontol Stratigr 105(3):397–416

Bossio A, Mazzei R, Monteforti B, Salvatorini G (2008) Stratigrafia del Neogene e Quaternario del Salento Sud-Orientale (con rilevamento geologico alla scala 1:25.000) [Neogene and quaternary stratigraphy of South-Eastern Salento (with geological survey at a scale of 1: 25,000)]. Geol Romana 38:31–60

Böttcher ME, Bernasconi SM, Brumsack H-J (1999) Carbon, sulfur, and oxygen isotope geochemistry of interstitial waters from the western Mediterranean. In: Zahn R, Comas MC, Klaus A (eds) Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results 161, Ocean Drilling Program, Texas A&M, College Station, TX, pp 413–421

Calò GC, Tinelli R (1995) Systematic hydrogeological study of the hypothermal spring (S. Cesarea Terme, Apulia), Italy. J Hydrology 165:185–205

Calò GC, Tinelli R (2004) Le acque sulfuree nel contesto idrogeologico dell’area di Torre Mozza di Ugento (Penisola Salentina, Puglia) [The sulfidic waters in the hydrogeological context of Torre Mozza di Ugento area) (Salento Peninsula, (Apulia)]. Acque Sotterranee [Underground Waters] 89:9–22

Calò GC, Spizzico M, Tinelli R, Zezza F (1983) Hydrogeological investigations on the area surrounding Santa Cesarea Terme springs (southern Apulia). Geol Appl Idrogeol 18(2):129–144

Canfield DE (2001) Biochemistry of sulfur isotopes. Rev Mineral Geochem 43:607–636

Canfield DE, Thamdrup B (1994) The production of 34S-depleted sulfide during bacterial disproportion of elemental sulfur. Science 266:1973–1975

Ciardo B (2006) Genesi e chimismo delle sorgenti sulfuree di Santa Cesarea Terme (Lecce) [Genesis and chemistry of the sulfidic springs in Santa Cesarea Terme, Lecce]. Master Thesis, Aldo Moro University, Bari, Italy

Corti E (1992) Relazione sul Convegno Nazionale di Speleologia di Castro, 14-15-16 settembre 1936 [Report on the National Speleological Conference in Castro, 14-15-16 September 1936]. Itiner Speleol 6:89–97

Cotecchia V (2014) Le acque sotterranee e l’intrusione marina in Puglia: dalla ricerca all’emergenza nella salvaguardia della risorsa [The underground waters and the marine intrusion in Apulia: from research to emergency in safeguarding the resources]. Memorie Descrittive della Carta Geologicad’Italia 92:416

Craig H (1961) Isotopic variation in meteoric waters. Science 133(3465):1702–1703

D’Amore F, Panichi C (1987) Geochemistry in geothermal exploration. Appl Geotherm 9:69–89

D’Amore JJ, Al-Abed SR, Scheckel KG, Ryan JA (2005) Methods for speciation of metals in soils. Rev J Environ Quality 34(5):1707–1745

D’Angeli IM, Vattano M, Parise M, De Waele J (2017) The coastal sulfuric acid cave system of Santa Cesarea Terme (southern Italy). In: Klimchouk AB, Audra P, Palmer AN, De Waele J, Auler A (eds) Hypogene karst regions and caves of the world. Springer, Heidelberg, Germany, pp 161–168

D’Angeli IM, Carbone C, Nagostinis M, Parise M, Vattano M, Madonia G. De Waele J (2018) New insights on secondary minerals from Italian sulphuric acid caves. Int J Speleol 47(3): 271–291

D’Angeli IM, Parise M, Vattano M, Madonia G, Galdenzi S, De Waele J (2019a) Sulfuric acid caves of Italy: a review. Geomorphology 333:105–122

D’Angeli IM, Ghezzi D, Leuko S, Firrincieli A, Parise M, Fiorucci A, Vigna B, Addesso R, Baldantoni D, Carbone C, Miller AZ, Jurado V, Saiz-Jimenez C, De Waele J, Cappelletti M (2019b) Geomicrobiology of a seawater-influenced active sulfuric acid cave. PLoS One 14(8):e0220706

D’Angeli IM, Parise M, Vattano M, Madonia G, De Waele J (2019c) Limestone and gypsum tablets weight loss in sulfuric acid speleogenetic caves of southern Italy. Proceedings of the 27th Int. Karstological School, Karst Research Institute, Ljubljana

De Giorgi C (1882) I bagni solfurei di Santa Cesarea in Terra d’Otranto [Sulfidic spa of Santa Cesarea Terme in the Otranto territor]. Riv Idrol Clim Med 4:8

De Giorgi C (1901) Le Terme Sulfuree di S. Cesaria sull’Adriatico [The sulfidic spa in Santa Cesarea along the Adriatic coastline]. Tipografia Adriano Salani, Lecce, Italy

De Giorgi C (1922) Descrizione fisica, geologica e idrografica della provincia di Lecce [Physical, geological and hydrographic description of the Lecce district]. Tipografia Editoriale Salentina, Lecce, Italy

De Waele J, Galdenzi S, Madonia G, Menichetti M, Parise M, Piccini L, Sanna L, Sauro F, Tognini P, Vattano M, Vigna B (2014) A review on hypogene caves in Italy. In: Klimchouk A, Sasowski ID, Mylroie J, Engel SA, Summers Engel A (eds) Hypogene cave morphologies, vol 18. Karst Water Institute, pp 28–30

De Waele J, Audra P, Madonia G, Vattano M, Plan L, D’Angeli IM, Bigot JY, Nobécourt JC (2016) Sulfuric acid speleogenesis (SAS) close to the water table: examples from southern France, Austria and Sicily. Geomorphology 253:452–467

Del Prete S, Iovine G, Parise M, Santo A (2010) Origin and distribution of different types of sinkholes in the plain areas of southern Italy. Geodin Acta 23(1/3):113–127

Delle Rose M, Leucci G (2010) Towards an integrated approach for characterization of sinkhole hazards in urban environments: the unstable coastal site of Casalabate, Lecce, Italy. J Geophys Eng 7:143–154

Delle Rose M, Parise M (2002) Karst subsidence in south-central Apulia Italy. Int J Speleol 31(1/4):181–199

Denitto F, Moscatello S, Palmisano P, Poto M, Onorato R (2006) Novità speleologiche, idrologiche e naturalistiche dalla Palude del Capitano (Psic It9150013) Costa Neretina (Lecce) [Speleological, hydrological and naturalistic news from the Capitano Marshland (Psic It9150013), Nardò Coast, Lecce]. Thalassia Salentina 29:99–116

Doglioni C, Mongelli F, Pieri P (1994) The Puglia uplift (SE Italy): an anomaly in the foreland of the Apenninic subduction due to buckling of a thick continental lithosphere. Tectonics 13(5):1309–1321

Eckardt F (2001) The origin of sulphates: an example of sulphur isotopic applications. Prog Phys Geogr 25(4):512–519

Edmund WM, Smedley PL (2013) Fluoride in natural waters. In: Selinus O, Alloway B, Centeno JA, Finkelmann RB, Fuge R, Lindh U, Smedley P (eds) Essentials of medical geology, 2nd edn. Springer, Heidelberg, Germany, pp 311–336

Egemeier SJ (1981) Cavern development by thermal waters. Nat Spel Soc Bull 43:31–51

Fernández-Cortès A, Cuezva S, Alvarez-Gallego M, Garcia-Anton E, Pla C, Benavente D, Jurado V, Saiz-Jimenez C, Sanchez-Moral S (2015) Subterranean atmosphere may act as daily methane sinks. Nat Commun 6:7003

Festa V, Fiore A, Parise M, Siniscalchi A (2012) Sinkhole evolution in the Apulian karst of southern Italy: a case study, with some considerations on sinkhole hazards. J Cave Karst Studies 74(2):137–147

Ford TD (1995) Some thoughts on hydrothermal caves. Cave Karst Sci 22(3):107–118

Freeman JT (2007) The use of bromide and chloride mass rations to differentiate salt-dissolution and formation brines in shallow groundwater of the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin. Hydrogeol J 15:1377–1385

Fry B, Ruf W, Gest H, Hayes JM (1988) Sulfur isotope effects associated with oxidation of sulfide by O2 in aqueous solution. Chem Geol 73:205–210

Funiciello R, Montone P, Parotto M, Salvini F, Tozzi M (1991) Geodynamic evolution of an intra-orogenic foreland: the Apulia case history (Italy). Boll Soc Geol Ital 110:419–425

Gabitov RI, Gagnoc AC, Guan Y, Eiler JM, Adkins JF (2013) Accurate Mg/Ca, Sr/Ca, and Ba/Ca ratio measurements in carbonates by SIMS and NanoDIMS and an assessment of heterogeneity in common calcium carbonate standards. Chem Geol 356:94–108

Galdenzi S (2001) L’azione morfogenetica delle acque sulfuree nelle grotte di Frasassi, Acquasanta Terme (Appennino Marchigiano - Italia) e di Movile (Dobrogea - Romania) [The morphogenetic activity of the sulfidic waters in the caves of Frasassi, Acquasanta (Marche Apennines, Italy), and Movile (Dobrogea - Romania)]. Grotte Italia 5(2):49–61

Galdenzi S, Maruoka T (2019) Sulfuric acid caves in Calabria (South Italy): cave morphology and sulfate deposits. Geomorphology 328:211–221

Galdenzi S, Menichetti M (1995) Occurrence of hypogene caves in a karst region: examples from central Italy. Environ Geol 26:39–47

Galdenzi S, Cocchioni F, Filipponi G, Morichetti L, Scuri S, Selvaggio R, Cocchioni M (2010) The sulfidic thermal caves of Acquasanta Terme (central Italy). J Cave Karst Stud 72(1):43–58

Gambini R, Tozzi M (1996) Tertiary geodynamic evolution of the southern Adria microplate. Terra Nova 8:593–602

Geldern R, Barth JA (2012) Optimization of instrument setup and post-run corrections for oxygen and hydrogen stable isotope measurements of water by isotope ratio infrared spectroscopy (IRIS). Limnol Oceanography Methods 10:1024–1036

Greve K, Nielsen E, Ladefoged O (2007) Evaluation of health hazards by exposure to strontium in drinking water. Toxicol Lett 172(1–7):S210

Gunn J (2007) Contributory area definition for groundwater source protection and hazard mitigation in carbonate aquifers. In: Parise M, Gunn J (eds) Natural and anthropogenic hazards in karst areas: recognition, analysis and mitigation. Geol Soc Lond Spec Publ 279:97–109

Hill CA (2000) Sulfuric acid, hypogene karst in the Guadalupe Mountains of New Mexico and West Texas, USA. In: Klimchouk AB, Ford DC, Palmer AN, Dreybrodt W (eds) Speleogenesis: evolution of karst aquifers. National Speleological Society, Huntsville, AL, pp 309–318

Hose LD, Pisarowicz JA (1999) Cueva de Villa luz, Tabasco, Mexico: reconnaissance study of an active sulphuric spring cave and ecosystem. J Cave Karst Stud 61(1):13–21

Hose LD, Palmer AN, Palmer MV, Northup DE, Boston PJ, DuChene HR (2000) Microbiology and geochemistry in a hydrogen-sulphide-rich karst environment. Chem Geol 169:399–423

ISO (2020) https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#search/code/. Accessed November 2020

Jagnow DH, Hill CA, Davis DG, DuChene HR, Cunningham KI, Northup DE, Queen JM (2000) History of the sulfuric acid theory of speleogenesis in the Guadalupe Mountains, New Mexico. J Cave Karst Studies 62(2):54–59

Jones DS, Polerecky L, Galdenzi S, Dempsey BA, Macalady JL (2015) Fate of sulfide in the Frasassi cave system and implications for sulfuric acid speleogenesis. Chem Geol 410:21–27

Karolytė R, Serno S, Johnson G, Gilfillan SMV (2017) The influence of oxygen isotope exchange between CO2 and H2O in natural CO2-rich spring waters: implications for geothermometry. Appl Geochem 84:173–186

Kim R, Cho H, Jeong J, Kim J, Lee S, Chung KW, Yoon H-S, Kim C-J (2020) Effect of sulfuric acid baking and caustic digestion on enhancing the recovery of rare earth elements from a refractory ore. Minerals 10:532

Klimchouk A (2017) Types and settings of hypogene karst. In: Klimchouk AB, Audra P, Palmer AN, De Waele J, Auler A (eds) Hypogene karst regions and caves of the world, Springer, Heidelberg, Germany, pp 1–39

Lawrence MG, Kamber BS (2007) Rare earth element concentrations in the natural water reference materials (NRCC) NASS-5, CASS-4, and SLEW-3. Geostand Geoanal Res 31(2):95–103

Liso IS, Parise M (2020) Apulian karst springs: a review. J Environ Sci Eng Technol 8:63–83

Longinelli A, Selmi E (2003) Isotopic composition of precipitation in Italy: a first overall map. J Hydrol 270:75–88

Lucas J, El Faleh EM, Prevot L (1990) Experimental study of the substitution of Ca by Sr and Ba in synthetic apatites. Geol Soc Lond Spec Publ 52(1):33–47

Macalady JL, Lyon EH, Koffman B, Albertson LK, Meyer K, Galdenzi S, Mariani S (2006) Dominant microbial population in limestone-corroding stream biofilms, Frasassi cave system, Italy. AEM 72(8):5596–5609

Maggiore M, Pagliarulo P (2003) Groundwater vulnerability and pollution sources in the Apulian region (southern Italy). Proceedings of the 2nd symposium “Protection of Groundwater from Pollution and Sea-water Intrusion”, Bari, Italy, 2003, pp 9–20

Maldonado MT, Allen AE, Chong JS, Lin K, Leus D, Karpenko N, Harris SL (2006) Copper-dependent iron transport in coastal and oceanic diatoms. Limnol Oceanogr 51:1729–1743

Margiotta S, Parise M (2019) Hydraulic and geomorphological hazards at wetland geosites along the eastern coast of Salento (SE Italy). Geoheritage 11:1655–1666

Martinis B (1962) Lineamenti strutturali della parte meridionale della Penisola Salentina [Structural lineaments of the southern portion of Salento peninsula]. Geol Romana 1:11–23

Mauget A (1875) Note geologiche sulla Provincia di Lecce [Geological notes on the Lecce province]. Tipografia Garibaldi, Lecce, Italy

Moretti M (1996) Tettonica sinsedimentaria e strutture sedimentarie dei depositi pleistocenici di Santa Cesarea Terme (LE) [Synsedimentary tectonics and sedimentary structures of the Pleistocene deposits in Santa Cesarea Terme, Lecce]. Proceedings Riunione del Gruppo Informale di Sedimentologia del CNR, Catania, Italy, pp 196–199

Mostardini F, Merlini S (1986) L’Appennino centro meridionale: sezioni geologiche e proposta di modello strutturale [The central southern Apennine: geological cross-sections and proposal of a structural model]. Mem Soc Geol Ital 35:177–202

Nordstrom DK, Jenne EA (1977) Fluorite solubility equilibria in selected geothermal waters. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 41:175–188

Ohmoto H, Rye RO (1979) Isotopes of sulfur and carbon. In: Barnes HL (ed) Geochemistry of hydrothermal ore deposits. Wiley, Chichester, UK, pp 509–567

Olarinoye T, Gleeson T, Marx V, Seeger S, Adinehvand R, Allocca V, Andreo B, Apaéstegui J, Apolit C, Arfib B, Auler A, Barberá JA, Batiot-Guilhe C, Bechtel T, Binet S, Bittner D, Blatnik M, Bolger T, Brunet P, Charlier JP, Chen Z, Chiogna G, Coxon G, De Vita P, Doummar J, Epting J, Fournier M, Goldscheider N, Gunn J, Guo F, Guyot JL, Howden N, Huggenberger P, Hunt B, Jeannin P-Y, Jiang G, Jones G, Jourde H, Karmann I, Koit O, Kordilla J, Labat D, Ladouche B, Liso IS, Liu Z, Massei N, Mazzilli N, Mudarra M, Parise M, Pu J, Ravbar N, Hidalgo Sanchez L, Santo A, Sauter M, Sivelle V, Skoglund RO, Stevanovic Z, Wood C, Worthington S, Hartmann A (2020) Global karst springs hydrograph dataset for research and management of the world’s fastest flowing groundwater. Sci Data 7:59

Onac BP, Sumrall JB, Tamas T, Povara I, Kearns J, Dârmiceanu V, Veres D, Lascu C (2009) The relationship between cave minerals and hypogene activity along the Cerna Valley (SW Romania). Acta Carsol 38(1):67–79

Onac BP, Wynn JG, Sumrall JB (2011) Tracing the source of cave sulfates: a unique case from Cerna Valley, Romania. Chem Geol 288:105–114

Onac BP, Effenberger HS, Wynn JG, Povara I (2013) Rapidcreekite in sulfuric acid weathering environment of Diana Cave, Romania. Am Mineral 98:1302–1309

Onorato R, Denitto F, Belmonte G (1999) Le grotte marine del Salento: classificazione, localizzazione e descrizione [The marine caves of Salento: classification, localization, and description]. Thalassia Salentina 23:67–116

Parise M (2011) Surface and subsurface karst geomorphology in the Murge (Apulia, southern Italy). Acta Carsol 40(1):79–93

Parise M, Ravbar N, Živanovic V, Mikszewski A, Kresic N, Mádl-Szonyi J, Kukuric N (2015) Hazards in karst and managing water resources quality. In: Stevanovic Z (ed) Karst aquifers: characterization and engineering. Professional Practice in Earth Sciences. Springer, Heidelberg, Germany, pp 601–687

Pepe M, Parise M (2014) Structural control on development of karst landscape in the Salento peninsula (Apulia, SE Italy). Acta Carsol 43(1):101–114

Pieri P, Festa V, Moretti M, Tropeano M (1997) Quaternary activity of the Murge area (Apulian foreland - southern Italy). Ann Geofis 40(5):1395–1404

Popa I, Brad T, Vaxevanopoulos M, Giurginca A, Baba S, Iepure S, Plaiasu R, Sarbu SM (2019) Rich and diverse subterranean invertebrate communities inhabiting Melissoreypa cave in central Greece. Travaux Institute Speleol Emil Racovita 58:65–78

Povara I, Simion G, Constantin M (2008) Thermo-mineral waters from the Cerna Valley basin (Romania). Studia UBB Geol 53(2):41–54

Regione Puglia (2008) Piano di gestione delle acque [Water management plan]. http://webapps.sit.puglia.it/freewebapps/ConsultaPubbPTA2019/. Accessed November 2020

Ricchetti G (1980) Contributo alla conoscenza strutturale della Fossa Bradanica e delle Murge (contribution to the structural knowledge of Bradanic trough and Murge). Boll Soc Geol Ital 49(4):421–430

Ricchetti G, Ciaranfi N, Luperto Sinni E, Mongelli F, Pieri P (1988) Geodinamica ed evoluzione sedimentaria e tettonica dell’Avampaese Apulo [Geodynamics and sedimentary and tectonic evolution of the Apulian foreland]. Mem Soc Geol Ital 41:57–82

Rozanski K, Araguás-Araguás L, Gonfiantini R (1993) Isotopic patterns in modern global precipitation. Clim Change Continental Isotopic Records 78:1–36

Rye RO, Etiope G, Belelle-Marchesini L, Papale D, Valentini R (2012) Geological carbon sources may confound ecosystem carbon balance estimates: evidence from a semi-arid steppe in southern of Spain. J Geophys Res Biogeosci 117:G03034

Santaloia F, Zuffianò LE, Palladino G, Limoni PP, Liotta D, Minissale A, Brogi A, Polemio M (2016) Coastal thermal springs in a foreland setting: the Santa Cesarea Terme system (Italy). Geothermics 64:344–361

Sarbu SM, Lascu C (1997) Condensation corrosion in Movile Cave, Romania. J Caves Karst Stud 59:99–102

Schoeller H (1962) Les Eaux Souterraines [Groundwater]. Mason et Cie, Paris, 642 pp

Seal RR (2006) Sulfur isotope geochemistry of sulfide minerals. Rev Mineral Geochem 61(1):633–677

Strauss H (1997) The isotopic composition of sedimentary sulfur through time. Palaeo 132:97–118

Summers Engel A, Stern LA, Bennett PC (2004) Microbial contributions to cave formation: new insights into sulphuric acid speleogenesis. Geology 32(5):369–372

Tadolini T, Bruno G (1993) The influence of geostructural setting upon water thermo mineralization in certain areas of Apulia (southern Italy), hydrogeological processes in karst terranes. IAHS Publ. no. 207, IAHS, Wallingford, UK, pp 75–83

Taylor SR, McLennan SM (1985) The continental crust: its composition and evolution. OSTI, Washington, DC, pp 311

Thompson CM (2015) Characterising copper biogeochemistry in marine systems, PhD Thesis, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia, pp 665

Tozzi M, Kissel C, Funiciello R, Laj C, Parotto M (1988) A clockwise rotation of southern Apulia? Geophys Res Lett 15(7):681–684

Tropeano M, Spalluto L, Moretti M, Pieri P, Sabato L (2004) Depositi carbonatici intrapleistocenici di tipo Foramol in sistemi di scarpata (Salento-Italia Meridionale) [Carbonate intrapleistocene deposits of Foramol type in continental shelf systems (Salento – southern Italy)]. Il Quaternario (Ital J Quatern Sci) 17(2/2):537–546

Vespasiano G, Apollaro C, Muto F, De Rosa R, Dotsika E, Marini L (2016) Preliminary geochemical characterization of the thermal waters of the Grotta delle Ninfe near Cerchiara di Calabria (South Italy). Rendiconti Online Soc Geol Ital 39:130–133

Vigor (2014) Energia dalla terra [Energy from the Earth]. http://www.vigor-geotermia.it. Accessed November 2020

Visintin B (1945) Studio sull’acqua della Grotta Gattulla delle Terme demaniali di S. Cesarea [Study on the water from Gattulla Cave in the Santa Cesarea Terme territory]. Annal Chim Appl 35(6–7):97–111

Wang XY, Zeng ZG, Chen S, Yin XB, Chen C-TA (2013) Rare earth elements in hydrothermal fluids from Kueishantao, off northeastern Taiwan: indicators of shallow-water, sub-seafloor hydrothermal processes. Chin Sci Bull 58(32):4012–4020

White WB (1969) Conceptual model for carbonate aquifer. Ground Water 7(3):15–21

Zeng Z, Ma Y, Wang X, Arthur Chen C-T, Yin X, Zhang S, Zhang J, Jiang W (2018) Elemental composition of crab and snail shells from Kueishantao hydrothermal field in the southwestern Okinawa Trough. J Mar Syst 180:90–101

Zerkle AL, Jones DS, Farquhar J, Macalady JL (2016) Sulfur isotope values in the sulfidic Frasassi cave system, Central Italy: a case study of a chemolithotrophic S-based ecosystem. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 173:373–386

Zezza F (1980) Le sorgenti ipotermali solfuree di Santa Cesarea Terme [The hypothermal sulfidic springs in Santa Cesarea Terme]. Salentum, Lecce, pp 1–2

Zuffianò LE, Palladino G, Santaloia F, Polemio M, Liotta D, Limoni PP, Parise M, Pepe M, Casarano D, Rizzo E, Minissale A (2013) De Franco R (2013) geothermal resource in a foreland environment: the Santa Cesarea Terme thermal springs (southern Italy). European Geothermal Congress 2013, Pisa, Italy, June 2013, pp 101–104

Zuffianò LE, Polemio M, Laviano R, De Giorgio G, Pallara M, Limoni PP, Santaloia F (2018) Sulphuric acid geofluid contribution on thermal carbonate coastal springs (Italy). Environ Earth Sci 77:517

Acknowledgements

We thank the Santa Cesarea Terme spa, and particularly Sergio Pistico, for their availability during sampling and monitoring campaigns. We thank Prof. Enrico Dinelli for lending the HACH DR/2010 spectrometer. Ilenia D’Angeli thanks Maria Luisa Garberi, Giovanni Belvederi and the Federazione Speleologica della Emilia-Romagna for use of the instrument MSA Altair 4X, and the Lions Club Napoli Megaride district 108 YA and the Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn for the travel grant “Paolo Brancaccio”.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Bari Aldo Moro within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Published in the special issue “Five decades of advances in karst hydrogeology”

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(PDF 470 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

D’Angeli, I.M., De Waele, J., Fiorucci, A. et al. Hydrogeology and geochemistry of the sulfur karst springs at Santa Cesarea Terme (Apulia, southern Italy). Hydrogeol J 29, 481–498 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-020-02275-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-020-02275-y