Abstract

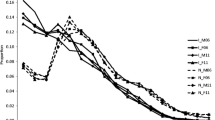

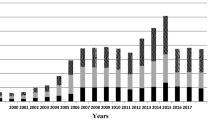

Using data from the 2011 National Household Survey 5-year migration question, we examined the migration of First Nations, Inuit and Métis between communities. Migration into and out of First Nations Reserves, small urban and rural areas, and Census metropolitan areas was estimated, as was migration into and out of Inuit Nunangat. We found that 5-year migration rates decreased in 2011 compared to previous census periods for Status First Nations, Inuit and Métis, but increased for non-Status First Nations. We also found that First Nations communities continued to be net gainers of Status First Nations migration.

Résumé

À l'aide des données de l'Enquête nationale auprès des ménages de 2011, nous avons examiné la migration intercommunautaire chez les Premières Nations, les Inuits et les Métis. Nous avons estimé la migration en provenance et en direction des réserves des Premières nations, des petites régions urbaines et rurales et des régions métropolitaines, de même que la migration en provenance et en direction de l'Inuit Nunangat. Nos résultats indiquent que les taux de migration quinquennaux ont diminué par rapport aux périodes de recensement précédentes pour les membres inscrits des Premières nations, les Inuits et les Métis, mais qu’ils ont augmenté pour les autochtones non-inscrits. Les communautés des réserves des Premières nations continuent d'être les gagnants nets du flux migratoires des Premières nations inscrites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The term “Indigenous” has come to be preferred to “Aboriginal” as a term to refer to First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. However, to be consistent with the terminology used in the Statistics Canada classifications and the 2011 NHS questions, we use “Aboriginal” when referring to the population identifying as First Nations, Inuit or Métis in the census or NHS.

Inuit Nunangat refers to the Inuit homelands of Inuvialuit (western Arctic), the territory of Nunavut, Nunavik (northern Quebec) and Nunatsiavut (northern Labrador).

An Indian Reserve or Settlement is land set aside by the Crown for the use of a First Nation.

We use the term “Status First Nations” to refer to those who are registered under the Indian Act of Canada, and who are elsewhere referred to as “Registered Indians.” “Non-Status First Nations” refers to those who identify culturally as First Nations but who are not registered under the Act.

A Census Metropolitan Area (CMA) is a city with an urban population of 100,000 or more and a core population of 50,000 or more.

The federal department of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) has since been dissolved, and replaced with two departments, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada and Indigenous Services Canada.

Note that the differences between these definitions and those used elsewhere, such as those that use Aboriginal identity only (e.g., Statistics Canada 2014), lead to different estimates of the size of these populations.

References

Aborignal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. (2013). Aboriginal Demographics from the 2011 National Household Survey. Ottawa: AANDC Planning, Research and Statistics Branch.

Andersen, C. (2014). “Métis”–Race, recognition and the struggle for Indigenous peoplehood. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Belanger, Y. D. (Ed.). (2009). Aboriginal Self-Government in Canada: trends and issues (3rd ed.). Saskatoon: Purich Publishing.

Bell, M., & Taylor, J. (2004). Conclusion: emerging research themes. In J. Taylor & M. Bell (Eds.), Population Mibility and Indigenous Peoples in Australasia and North America (pp. 262–267). London: Routledge.

Bérard-Chagnon, J. (2017). Comparison of place of residence between the T1 family file and the census: evaluation using record linkage. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Biddle, N. (2010). Indigenous migration and the labour market: a cautionary tale. Australian Journal of Labour Economics, 13(3), 313.

Bonesteel, S. (2008). Canada’s relationship with Inuit: a history of policy and program development. Ottawa: Indian and Northern Affairs Canada.

Bonhert, N. (2013). Migration: interprovincial, 2009/10 and 2010/11 Report on the Demographic Situation in Canada. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Boyd, M. (1989). Family and personal networks in international migration: recent developments and new agendas. International Migration Review, 23(3), 638–670.

Canadian Bar Association Aboriginal Law Section. (2016). Bill S-3– Indian Act amendments (elimination of sex-based inequities in registration). Ottawa: Canadian Bar Associoation.

Clatworthy, S. (2004). Re-assessing the population impacts of Bill C-31. Ottawa: Indian and Northern Affairs Canada.

Clatworthy, S., & Cooke, M. (2001). Patterns of registred Indian migration between on- and off-reserve locations. Ottawa: Research and Analysis Direcorate, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada.

Clatworthy, S., & Norris, M. J. (2007). Aboriginal mobility and migration: trends, recent patterns, and implications: 1971-2001. In J. P. White, S. Wingert, D. Beavon, & P. Maxim (Eds.), Aboriginal Policy Research: Moving forward, making a difference (Vol. IV, pp. 207–234). Toronto: Thompson Educational Publishing.

Cooke, M., & Bélanger, D. (2006). Migration theories and First Nations mobility: towards a systems perspective. Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology, 43(2), 141–164.

Cooke, M., & McWhirter, J. (2011). Public policy and Aboriginal peoples in Canada: taking a life-course perspective. Canadian Public Policy, 37(Supplement 1), S15–S31.

Cooke, M., & O’Sullivan, E. (2014). The impact of migration on the First Nations community cell-being index. Social Indicators Research, 122(2), 371–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0697-4.

Cooke, M., & O’Sullivan, E. (2015). The impact of migration on the First Nations community well-being index. Social Indicators Research, 122(2), 371–389.

Cooke, M., Mitrou, F., Lawrence, D., Guimond, E., & Beavon, D. (2007). Indigenous well-being in four countries: an application of the UNDP’S human development index to indigenous peoples in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 7(1), 9.

Delgamuukw v. British Columbia (1997). 3 SCR 1010, 1997 CanLII 302 (SCC). http://canlii.ca/t/1fqz8. Accessed 30 Nov 2019.

Distasio, J., Sylvestre, G., & Wall-Wieler, E. (2013). The migration of indigenous peoples in the Canadian prairie context: exploring policy and program implications to support urban movers. Geography Research Forum, 33, 38–63.

Fawcett, J. T. (1989). Networks, linkages, and migration systems. International Migration Review, 23(3), 671–680.

Guimond, E., Kerr, D., & Beaujot, R. (2004). Charting the growth of Canadian Aboriginal populations: problems, options and implications. Canadian Studies in Population, 31(1), 33–82.

Harris, J. R., & Todaro, M. P. (1970). Migration, unemployment and development: a two-sector analysis. The American Economic Review, 60(1), 126–142.

Maaka, R., & Fleras, A. (2005). The politics of indigeneity: challenging the state in Canada and Aotearoa. New Zealand: Otago University Press.

Mendelson, M. (2004). Aboriginal people in Canada’s labour market: work and unemployment, today and tomorrow (Vol. 1). Ottawa: Caledon Institute of Social Policy.

Mitrou, F., Cooke, M., Lawrence, D., Povah, D., Mobilia, E., Guimond, E., & Zubrick, S. R. (2014). Gaps in Indigenous disadvantage not closing: a census cohort study of social determinants of health in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand from 1981–2006. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 201.

Moyser, M. (2017). Aboriginal people living off-reserve and the labour market: estimates from the labour force survey, 2007-2015. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Norris, M. J., & Clatworthy, S. (2011). Urbanization and migration patterns of Aboriginal populations in Canada: a half century in review (1951 to 2006). Aboriginal Policy Studies, 1(1), 13–77.

Norris, M. J., & Clatworthy, S. (2014a). Aboriginal mobility and migration in Canada: patterns, trends, and implications, 1971 to 2006. In F. Trovato & A. Romaniuk (Eds.), Aborignal Populations: Social, Demographic, and Epidemiological Perspectives (pp. 119–160). Alberta: University of Alberta Press.

Norris, M. J., & Clatworthy, S. (2014b). Aboriginal mobility and migration in Canada: patterns, trends, and implictions, 1971 to 2006. In F. Trovato & A. Romaniuk (Eds.), Aboriginal Populations: Social, Demographic and Epidemiological Perspectives (pp. 119–160). Alberta: University of Alberta Press.

Patrick, D., & Tomiak, J.-A. (2008). Language, culture and community among urban Inuit in Ottawa. Études/Inuit/Studies, 32(1), 55–72.

Pendakur, K., & Pendakur, R. (2011). Aboriginal income disparity in Canada. Canadian Public Policy, 37(1), 61–83.

Peters, E. (1994). Demographics of Aboriginal Peoples in Urban Areas in relation to Self-Government. Ottawa, Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development.

Petrov, A. N. (2007). Revising the Harris-Todaro framework to model labour migration from the Canadian northern frontier. Journal of Population Research, 24(2), 185–206.

Rotondi, M. A., O’Campo, P., O’Brien, K., Firestone, M., Wolfe, S. H., Bourgeois, C., & Smylie, J. K. (2017). Our Health Counts Toronto: using respondent-driven sampling to unmask census undercounts of an urban indigenous population in Toronto, Canada. BMJ Open, 7(12), e018936.

Siggner, A. J. (1977). Preliminary results from a study of 1966-1971 migration patterns among status Indians in Canada. Ottawa: Indian and Eskimo Affairs Program.

Smith, Wayne R. (2015). The 2011 National Household survey–the complete statistical story. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/blog-blogue/cs-sc/2011NHSstory. Accessed 30 Oct 2019.

Statistics Canada. (2010). Aboriginal peoples technical report, 2006 Census, Second Edition. Cat No. 92-569-X. Ottawa: Minister of Industry.

Statistics Canada. (2011). 2006 Census: aboriginal peoples in Canada in 2006: Inuit, Métis and First Nations, 2006 Census: Inuit. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Statistics Canada. (2012a). Census Dictionary, Census Year 2011. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Statistics Canada. (2012b). National Household Survey Dictionary, 2011. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Statistics Canada. (2013a). Aborignal Peoples Reference Guide, National Household Survey 2011. Cat No. 99-011-XWE2011006. Ottawa: Minister of Industry.

Statistics Canada. (2013b). Incompletely enumerated Indian reserves and settlements. Retrieved Novermber 10, 2015, from https://www.12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/ref/aboriginal-autochtones-eng.cfm. Accessed 10 Nov 2015

Statistics Canada. (2013c). National Household Survey User Guide, 2011. Cat No. 99-001-XWE2011001. Ottawa: Minister of Industry.

Statistics Canada. (2014). Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: First Nations People, Métis and Inuit. Retrieved April 4, 2015, from http://www.12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-011-x/99-011-x2011001-eng.cfm

Statistics Canada. (2015a). Aboriginal statistics at a glance’ 2nd Edition. Catalogue No. 89-465-X2015001. Ottawa: Statistics Caanda.

Statistics Canada. (2015b). Mobility and migration reference guide, national household survey, 2011. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Statistics Canada. (2017). Aboriginal peoples in Canada: Key results form the 2016 Census. The Daily. Retrieved October 18, 2018, from https://www.150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171025/dq171025a-eng.htm?indid=14430-1&indgeo=0. Accessed 18 Oct 2018

Tjepkema, M., Wilkins, R., Senécal, S., Guimond, É., & Penney, C. (2009). Mortality of Métis and registered Indian adults in Canada: an 11-year follow-up study. Health Reports, 20(4), 31.

Tomiak, J.-A., & Patrick, D. (2010). Transnational migration and indigeneity in Canada: a case study of urban Inuit. In M. C. Forte (Ed.), Indigenous Cosmopolitans: Transnational and Transcultural Indigeneity in the Twenty-First Century (pp. 127–144). New York: Peter Lang.

Zelinsky, W.. (1971). The hypothesis of the mobility transition. Geographical Review, 219–249.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cooke, M., Penney, C. Indigenous Migration in Canada, 2006–2011. Can. Stud. Popul. 46, 121–143 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42650-019-00011-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42650-019-00011-w