Abstract

Recommendation 6 of the Commission on Religious Education’s Final Report has focused attention on teacher preparation in England for Religious Education (RE) during primary Initial Teacher Education (ITE). It recommends at least twelve hours for ‘all forms of primary ITE’, challenging the current provision of many primary ITE providers. Information gathered by the National Association of Teachers of Religious Education (NATRE) and others demonstrates the need to improve not only the hours taught, but also the quality of provision across all training routes. Many beginner teachers lack confidence in their RE subject knowledge and fear causing offence. If RE is to play a valid part in a twenty-first century primary curriculum, training needs to address these concerns and develop understanding of the complex knowledge the subject requires. This paper explores aspects of knowledge in RE, the importance of relating developing practical wisdom to subject knowledge and considers a project which responds directly to the Commission’s report.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The Commission on Religious Education was established by the Religious Education Council (REC) for England and Wales in 2016. Its purpose was to ‘review the legal, educational and policy frameworks for religious education’ in England (CORE 2017, p. 16). Although established by the REC, the Commission was independent and had the purpose of improving ‘the quality and rigour of religious education and its capacity to prepare pupils for life in modern Britain’ (CORE 2017, p. 106). Its Final Report, Religion and Worldviews: The Way Forward, a national plan for RE (CORE 2018) describes the situation in England where Religious Education (RE) is in a parlous state in many schools. (APPG 2013; Ofsted 2013; NATRE 2017; CORE 2017, 2018; Myatt 2020; Brine and Chater 2020). It outlines reasons for the decline in RE provision in primary/elementary (pupils aged 5–11) and secondary (pupils aged 11–18) schools and proposes eleven recommendations which could improve the understanding and delivery of RE in England if they are developed further. The Report has already galvanised academics, consultants and teachers into new thinking about RE or Religion and Worldviews (RW), as one of the recommendations calls the subject. In particular there have been keen debates around the new name (Recommendation 1), the need for a National Entitlement (Recommendation 2) and the suggested removal of the right to withdraw pupils from RE (Recommendation 11), as well as the proposal for local advisory networks (Recommendation 8). It is important to see the recommendations as a complete and interconnected group, which together set out to provide the impetus for a multi-faceted improvement in the status and provision of the subject. They also need to be seen within the context of a wider range of publications concerning RE and the resulting debate about the nature, content and intentions of the subject (Conroy et al. 2013; Clarke and Woodhead 2015, 2018; The Woolf Institute 2015; Dinham and Shaw 2015; CORE 2017; Castelli and Chater 2018; Chater 2020; Freathy and John 2019). The Commission calls for responses ranging from policy makers and inspectors to local SACREs and classroom teachers. It sets out its own agenda, but it is also embedded in the challenges and developments set out within other reports from the RE community in England and the UK.

2 Recommendation 6

So far there has been less discussion and contention around Recommendation 6 which states:

All Initial Teacher Education (ITE) should enable teachers, at primary and where relevant at secondary level, to teach Religion and Worldviews based on the National Entitlement and with the competence to deal with sensitive issues in the classroom, and the teachers’ standards should be updated to reflect this. In order to support this, the following should be implemented.

- a.

There should be a minimum of 12 h of contact time for Religion and Worldviews for all forms of primary ITE including School Direct and other school-based routes.

- b.

…Funding should be allocated for Subject Knowledge Enhancement for primary.

- d.

…Two new modules for Religion and Worldviews should be developed for primary ITE, and also made available as continuing professional development (CPD) modules: one for those with limited experience and one for those with proficiency in the subject…These modules should focus on the delivery of the national programmes of study [Recommendation 3] (CoRE 2018, p. 15)

The call for improvement in the provision of RE in primary ITE is the focus of this article because the current situation is uneven, fragile in many cases, under-researched and unpublicised. There are different types of ITE route in England, from Higher Education Institutions (HEIs), which are involved in undergraduate and post graduate courses, to School Centred Initial Teacher Training routes (SCITTs), School Direct and Teach First initiatives. Since the CORE report, some primary ITE/ITT providers have reviewed and in some cases increased their provision in terms of hours, recognising the need to develop RE as part of their Foundation Subjects’ provision. This may be further stimulated by the Office for Standards in Education, Children's Services and Skills’ (Ofsted) recent call for a ‘broad and balanced curriculum’ in schools (Ofsted 2019a, 2019b) and the resultant impact on ITE inspection (Ofsted 2020). It is difficult to judge the impact of the recommendation itself at this stage, but it is undoubtedly important that primary RE is specifically identified as needing attention at the ITE level. Although changes to Teacher Standards and financial support for primary CPD have not yet been forthcoming, it is important that what has been suggested is acknowledged and acted upon as far as possible by the RE community in England. Primary RE can be missing from or given a very short time in beginner teacher training, taught by non-specialists and marginalised or generalised through approaches which do not identify the individuality of the subject (CORE 2018).

Recommendation 6 calls for twelve hours of training time, which is a useful, if blunt, instrument of measurement. The other recommendations flesh out the potential quality and content, but as a baseline, time can begin to demonstrate the weak position of RE on Primary training routes. NATRE has indicated in successive reports that the amount of ITE training recorded by primary teachers in RE has reduced over the years (NATRE 2013, 2016, 2018) despite calls in Ofsted reports to improve provision (Ofsted 2007, 2010, 2013). The trends show a worrying decline in training opportunities in primary ITE. Despite some courses offering RE as a specialism, where beginner teachers can receive specific RE training often exceeding twenty hours of provision, generalist trainees, or those who are pursuing another specialism, on average receive between 0 and 3 h (CORE 2018, p. 46). The stark use of hours here demonstrates the inadequacy of RE training in these circumstances. Many beginner teachers are not receiving enough time to consider the subject, its requirements, subject content or appropriate pedagogies and this perpetuates the problems around content and delivery which are highlighted by many writers (Castelli and Chater 2018; Freathy and John 2019; Brine and Chater 2020; Kueh 2020).

In contrast, twelve hours of RE can provide beginner teachers with the opportunity to be introduced to the aims of the subject, the ‘complex, diverse and plural nature’ of its subject matter (CORE 2018, p. 6), aspects of and approaches to knowledge and pedagogies which are appropriate to primary pupils. It provides opportunity for discussions, activities, reflection and an appreciation of how valuable the subject can be for pupils. Twelve hours creates time for a more nuanced understanding of belief and unbelief in individuals and communities. It can provide time for beginner teachers to consider their own positions and understandings, and develop professional skills and personal confidence to teach a subject about which many have anxieties. Above all, twelve hours can begin to challenge essentialised and often stereotypical views which exist around religions and worldviews and encourage a better understanding of what subject knowledge can mean in the primary context (Whitworth 2017). This recommendation could rapidly improve the status and quality of primary RE in ITE, but to date there has not been a marked improvement in provision.

3 RE in primary schools

Training in Primary ITE in RE is also impacted by the position the subject holds in many schools, including those which provide placements or are centres for training. School experience is seen by many beginner teachers as the most authentic part of their training and their attitudes are greatly influenced by what they see there. The uneven quality of RE being taught in primary schools has long been recognised (Ofsted 2007, 2010, 2013; APPG 2013; NATRE 2016, 2018; CORE 2018). There are a number of problems, including: breaches in school observation of the legal entitlement to RE, low status for RE as a subject in the curriculum, diminished time allocation within the busy primary timetable, underdeveloped systems of assessment and teachers’ lack of experience and confidence due to lack of RE training and on-going professional development. Some schools employ other teachers or Higher Level Teaching Assistants (HLTAs) to provide the RE teaching in their schools, resulting in some class teachers being less aware of RE’s content and relevance in the lives of their pupils and therefore not making links to the wider curriculum. All these impact on beginner teachers’ experiences. Research into one provider indicated that a quarter of undergraduates did not have experience of RE in at least two out of their three placements (Whitworth 2017) and PGCE and School Direct trainees also did not have regular opportunities to observe and teach RE within their training. If quality in RE in ITE is focused on experience being gained in schools, it is not sufficiently dependable and may not make a reliable contribution to beginner teachers’ training.

More positively, good examples of practice can be found across England, from inspirational Agreed Syllabuses to dedicated organisations, local groups and teachers who promote the subject by outstanding teaching and resourcing. Individual projects such as Understanding Christianity (CEM 2016), RE-searchers (Freathy et al. 2015) and Primary 1000 (NATRE 2019a) are making a considerable impact at school level. Recent information gathered by NATRE (2019b) on reports written under the new Ofsted framework for inspection (Ofsted 2019a) indicates that RE is being considered in these inspections and ‘Deep Dives’, which collaboratively gather evidence with the school on intent, implementation and impact, are including RE in the subjects inspected. These are positives, as inspection can assist in raising the subject’s profile and may contribute to improved teaching of RE in primary schools, which in turn may influence RE’s quality in ITE.

4 Content and knowledge in primary RE

The content of RE is considered in CORE’s Recommendation 2 for a National Entitlement. Approaches to content are currently very varied between Agreed Syllabuses and the Report states that the subject would benefit from a national body to draw up non-statutory programmes of study (Recommendation 3) to assist teachers in designing content and resources. Underlying such decisions are perceptions of knowledge which need to be identified and interrogated so that there is cohesion in establishing content.

There are a variety of approaches to knowledge currently used in RE and CORE advocates a consciously multi-disciplinary approach. Georgiou and Wright (2018) identify that in their experience much primary content is based on a human and social sciences understanding of content, in contrast to more philosophical approaches in secondary schools. They argue for a balance between theological, philosophical and human and social science approaches to knowledge across school provision. Kueh (2018, 2020) recognises the problems RE has in this area and identifies a need for a clearer agreed rationale to underpin approaches to knowledge, which are currently over-complex because of RE’s own heritage in England. He argues for a reassertion of an academic justification for the subject (also called for in the CORE Report), using the concept of ‘powerful’ knowledge which recognises diversity and complexity and contextualises substantive knowledge in a multi-disciplinary framework using conceptual understandings. Freathy and John (2019) argue that the inherent complexity and fluidity of religions and worldviews should be recognised when approaching selection of content and that the study of RE should be focused on both the content of worldviews and the process of study itself. Each of these approaches agrees on the need for a multi-disciplined approach to knowledge and, as work on a National Entitlement progresses, it is to be hoped that the academic study of RE will become better defined.

5 An example from one HEI primary ITE provider

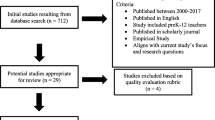

How can Primary ITE beginner teachers be introduced to this debate about complex knowledge when many teachers already identify lack of subject knowledge as a major hurdle in teaching RE (NATRE 2013, 2016, 2018; CORE 2018)? Research undertaken with primary undergraduate beginner teachers in one university-led provision reported that 40% identified as having concerns about teaching RE (total sample size 279, Whitworth 2017). Those with no experience indicated more concerns than those who had taught RE on placement.

Further analysis indicated that their concerns subdivided into five main areas (Fig. 1). The largest was lack of secure subject knowledge, but there were also issues around sensitivities, anxiety about parents’ responses to the subject, a fear that children might know more than the beginner teachers knew themselves and a discomfort about compromising their own beliefs when asked to teach about religions and worldviews. This indicated that beginner teachers require both academic and professional training to respond to their concerns.

Areas of concern expressed by beginner teachers. (Average over 6 years, total sample size 279) (Whitworth 2017, p. 130)

Further enquiry into expectations of ‘subject knowledge’ for their taught RE module revealed that many beginner teachers expected they would receive mostly substantive information which could be repeated for children to learn. Richard Kueh (2020) articulates this continuing issue clearly when he writes of:

a reductive, fact-based curriculum, accompanied by a naïve pedagogical application of direct instruction (Kueh 2020, 131).

Some beginner teachers clearly wanted to be told what to teach so that they could be confident about accuracy. Yet when this attitude to knowledge was critiqued, they recognised that their own experiences of religious and non-religious worldviews were diverse and did not fit into essentialised descriptions. As understandings of ‘subject knowledge’ were problematized, more real-life nuances of religious belief, unbelief and practice were discussed and a new understanding of how religion and worldviews might be taught started to emerge. Beginner teachers began to develop their understandings of what constituted epistemic knowledge. Georgiou and Wright’s identification of a human and social sciences approach (2018) emerged as the beginner teachers’ dominant model, with a focus on practices, but within this, issues of complexity and diversity could now begin to be addressed.

A three-layered representation of religions (Religious tradition, community and individual, Jackson 1997; Whitworth 2009) was used to identify complexity in religions and worldviews. This enabled beginner teachers to understand and navigate the realities they discovered when discussing their own ideas, beliefs and practices. They recognised that over-simplification could lead to stereotypical descriptions and inaccuracies when related to lived experience. They also identified the importance of including the diverse experiences of their pupils. At first this may appear to risk further complicating their anxiety about subject knowledge, but in practice they realised acknowledgement of diversity resolved some of their concerns. They continued to recognise their professional responsibility to research individual religions and worldviews so that they could teach them more knowledgeably, but also recognised that they could engage in more complexity when discussing religious belief and practice by acknowledging nuance and difference as well as similarity. This moved them from a model of simplified instruction towards one of more complex facilitation. Finding out about religions and worldviews additionally enabled them to consider investigative and dialogic pedagogical models, which they had already met in other subjects and felt able to reimagine into an RE context. These examples of feedback comments, from beginner teachers at the end of their taught RE module, demonstrate the changes in their perceptions of what RE knowledge could be:

This has made me realise it is not only about giving children knowledge, it’s more holistic—about how the child relates to the knowledge and how it affects their thinking.

Now I can talk to children about their own lives (Whitworth 2017, pp. 150–151).

These comments indicated that by problematizing perceptions of knowledge, beginner teachers could recognise and reject over-simplified accounts of religions, which could create objects of study far-removed from the experiences of many of their primary pupils. Instead positionality became more relevant and diversity was acknowledged and accommodated in their teaching. Beginner teachers were encouraged to consider the difference between providing knowledge and translating that knowledge into meaningful learning in specific situations, drawing particularly on investigative and dialogic pedagogies. If, for example, student teachers were aware of the religious and cultural backgrounds of their pupils, they were able to adapt their teaching to complement and enhance the understandings of those pupils. Different classes required different planning because of the pupils within the class and ‘off the peg’ lessons were not sufficient as they did not include this refinement.

Beginner teachers’ fear of ‘not knowing enough’ can therefore be responded to by interrogating their understandings of knowledge and also by contextualising subject knowledge within their understanding of primary pedagogy. Knowledge of how to teach includes learning to make judgements within specific contexts and situations. What is taught and how it is taught is chiefly determined by consideration of who is being taught. The Aristotlean concept of phronesis (practical wisdom) (Aristotle 350BCE/1999; Flyvbjerg 2001; Kessels and Korthagen 2001; Kinsella and Pitman 2012; Whitworth 2017) is particularly helpful here because beginner teachers can be challenged to consider what informs their ethical decision-making about teaching in differing circumstances. Phronetic knowledge develops through the process of learning to teach and reflecting on how learning has occurred. It is not technical teacher craft but perceptual wisdom informed by values. Engaging beginner teachers’ growing understanding of phronesis with understanding of complex and nuanced RE helps to develop the application of context-related subject knowledge. It is no longer sufficient to know information and deliver it, lessons should provide learning opportunities which engage both personal and academic development for pupils. As beginner teachers become more confident in their practical decision-making, this can help them decide how to proceed with issues which require sensitivity. A more self-aware approach, which harnesses a more complex understanding of epistemic knowledge and phronesis, the relationship between theoretical knowledge and practical wisdom, can assist beginner teachers’ ‘competence to deal with sensitive issues in the classroom’ (CORE 2018, p. 15).

6 Responding to the commission through a project

A project specifically designed to address Recommendation 6 began in 2018. Its purpose was to explore what could be included in twelve hours’ provision and disseminate examples of good practice. An on-line twelve hour course for beginner teachers was envisaged as a precursor to the two modules, one for beginners and another for those with proficiency, recommended by the Commission. It was designed to be flexible enough for ITE tutors and teachers to use to supplement their own teaching or, in cases where there was no other provision, as a course which would introduce beginner teachers to some of the current issues in RE, approaches to subject knowledge and consideration of primary-oriented pedagogies which would inform their understanding of good RE in the classroom. Materials were designed using knowledge drawn from a variety of different types of provision including HEIs and SCITTs. Throughout the project it was agreed that ideally beginner teachers would be taught face-to-face by tutors and teachers, but where that was not possible, an on-line course, Teach:RE Primary: an Introduction, (Wright et al. 2019a) could provide a support for beginner teachers, newly and recently qualified teachers and HTLAs who taught RE in their primary schools. In addition to the beginner teacher course, a second resource, The Toolkit for Primary Religious Education ITT providers (Wright et al. 2019b), was also designed to provide examples of resources and activities which could be used with beginner teachers as part of taught courses. There was informal evidence that tutors and teachers who were not RE specialists were, in some circumstances, being asked to teach beginner teachers and this document was intended to support them by providing materials which informed them of the Commission’s vision for RE as well as considering the development of subject knowledge and pedagogy.

7 Designing the resources

These resources were designed with the recognition that the skills sets and requirements of beginner primary teachers are different from those of secondary, in particular recognising the relationship between class teachers and their pupils and beginner teachers’ growing understanding of learning and teaching with young children. Unlike secondary teachers, their expertise is in the nurture of learning across a wide range of subjects and pupils’ development is perceived more holistically. Combining understandings taught elsewhere on ITE courses with RE was therefore seen as a helpful bridge for beginner teachers’ understandings. Recognising, for example, what makes a good lesson in a generic sense could then be applied and refined for RE lessons. This was also designed to prevent the risk that planning content and selecting pedagogies were seen as less important in RE than in other subjects.

Early discussions considered the dynamics needed for the Teach:RE Primary course. Beginner teachers would need to feel supported and extension should be provided for those who had studied RE at A level or beyond. Personal experiences of RE, personal positions in relation to belief and attitudes, opportunities encountered in school-based practice and the range of types of primary school where practice might occur had to be factored into decision-making about content and approach. Access to a range of religions and worldviews would vary across England, which could impact on a student teacher’s understanding of some activities. Priority was given to those who might come with very limited personal knowledge of religions and who were practising in schools without a designated religious character. Those who had placements in faith or church schools were likely to receive a more supported opportunity to teach RE (NATRE 2018) and beginner teachers were more likely to consider their own position when placed in these schools. NATRE research indicated that it was in schools which did not have a religious character that RE was less likely to be taught on a regular basis (2018), suggesting that beginner teachers were less likely to be given opportunities to teach or observe the subject.

The Teach:RE Primary course is designed to be used flexibly by beginner teachers and tutors, so a common core from most provisions is identified. It contains an introduction and background to teaching RE, a section on subject knowledge and a section on approaches to teaching and learning. These three elements are seen as equally important for the unsupported learner. Accessibility to the course is achieved by placing it on a well-known RE website. The course is freely available, with the only requirement being that participants register to access the materials. The website has established experience in designing and running on-line courses and one of the co-writers of the course had previously designed materials for teachers on the site. The twelve hour length was already determined by the Commission’s report and it was decided to avoid imposing any timeframe for completion as different audiences might have different requirements. Those who complete the whole course are offered a certificate of completion, which although carries no academic credit can be seen as a sign of engagement with the materials.

The challenge was to present material which is both engaging and achievable for beginner teachers who may have little knowledge or support in learning about RE and also seek to challenge their perceptions about the subject. One way to make the course relevant to each beginner teacher’s circumstance is to encourage reflections on their own school placements. Each activity therefore comprises of a series of short, exploratory and investigative sections, followed by more formal responses which can be discussed with a mentor, teacher or tutor. It is hoped that face-to-face engagement will promote a dialogue about the provision for RE in the schools where beginner teachers are trained. During the activities there are clear references to the CORE report. This is intended to familiarize schools and training centres as well as beginner teachers with the new recommendations, so that face-to-face discussions might also inform schools about the Commission’s work, if they are unfamiliar with it. Within each activity there are tasks which link the participant to resources or groups (some on-line) which could support their future teaching. These include videos, apps and social media so that they become aware of the wider RE community which could offer assistance as their careers develop.

The subject knowledge section of the on-line resource is designed to assist the participants in considering their own worldview. The National Entitlement is introduced so that the complex nature of religions and worldviews is addressed from the beginning. The material used emphasises the experiences of individuals within a belief or worldview as well as introducing reliable resources which are designed for teacher use in the classroom or for personal study. In this way Christians, Muslims or Hindus are introduced as well as Christianity, Islam or the Hindu Tradition. This enables participants to engage with lived experience, thereby presenting religious belief as nuanced, which is further supported by the use of film material. A substantial resources section is included so that teachers can continue to develop their understandings over time. The approaches to subject matter explained earlier in the face-to-face course are echoed by asking participants to contextualise the material they are studying within their own experience of a classroom setting. This enables them to draw together subject knowledge and practical teaching skills to encourage them to interrogate the place and nature of knowledge in their own teaching.

The Toolkit for Primary Religious Education ITT providers is designed to assist teacher trainers on all ITE routes. It is also freely available and comprises of approaches and activities drawn from experienced teachers, tutors and advisors which can be used in practical teaching sessions. No one approach is prioritised and a range of activities are presented so that tutors and teachers can select according to their own approaches. The Toolkit is divided into three layers (Fig. 2).

The design of the Toolkit for RE ITE providers (Wright et al. 2019b, p. 5)

This develops from the structure of the Teach:RE Primary course. The first, marked Essential, focuses on a rationale for RE. It contains information for tutors on RE’s purpose and introduces CORE’s recommendations. The second layer, Important, is divided between subject knowledge and pedagogy and practice. As indicated in the Teach:RE Primary course, both these aspects were seen as of equal importance. They have a clear relationship and both seek to improve beginner teachers’ competence and confidence.

The third layer, Desirable, is sub-divided into 6 sections: RE and the Local Context, Spiritual, Moral, Social and Cultural development, Visits and Visitors, RE and Inclusion, Safe Spaces and Controversial Issues, and Cross-Curricular RE. These identify elements taught in longer RE courses in primary ITE for tutors to consider. Those courses which offer a primary specialism in RE already have their own programmes, but this section may encourage others to expand their RE provision further.

The Commission recommends two resources to be developed for ITE and CPD based on the National Entitlement. It is hoped that these two resources will provide insight into how the one for those with limited experience can develop both subject knowledge and teaching and learning when the National Entitlement has been decided.

8 Responses to the Teach:RE primary course during COVID 19

The Teach:RE Primary course was used by some HEIs and SCITTs from September 2019, but the arrival of COVID 19 resulted in a move to on-line teaching for most ITE providers. By July 2020 over 1,200 participants had signed up for the course, because a number of ITE courses adopted it as an alternative or supplement to their own provision.

This unexpected surge enabled an initial on-line survey to be sent out to assess the impact of the course on participants. It was completed by 5% (60 responses) and indicated that:

40% heard of the course through their ITE provider (HEIs and SCITTs) |

40% undertook the course specifically to develop their subject knowledge |

25% wanted to develop their understanding of RE and wider expertise |

95% of those responding had either completed or intended to complete the whole course |

75% planned to request a certificate of completion |

85% felt their understanding of Religion and Worldviews as a school subject had been enhanced |

85% felt more confident about teaching Religion and Worldviews |

Although a limited response, this demonstrated the appetite for primary-focused training for beginner teachers. Qualitative feedback about specific activities indicated that those designed to promote understanding of the nature of RE and subject knowledge were particularly well-received. Most respondents commented that the course also impacted on their understanding of teaching RE and they could see the benefits of all aspects of the course. Comments included:

… my subject knowledge has improved … in a range of areas; I also have a greater understanding of how to teach RE effectively as well as gaining more knowledge. The course had also given me a range of resources which I can access to continue to enhance my subject knowledge so I can continue to develop. I feel more confident in my ability to teach RE and how to do it effectively.

Additions and amendments to the course will be made in the light of the feedback and further participant and tutor research will be carried out during the coming academic year.

9 Conclusion

The CORE recommendations for Primary ITE in RE, if adopted, could make significant improvements to beginner teachers’ understanding and practice in primary RE, because an increase in time allows more recognition of the content and purposes of primary RE and engages beginner teachers in more complex subject knowledge and a range of pedagogies. Currently Recommendation 6 does not have sufficient attention from ITE providers, but changes in emphasis in the curriculum, such as ensuring a ‘broad and balanced’ provision (Ofsted 2019a, b), offer an opportunity for more attention to be shown to RE. ITE responses to beginner teachers’ concerns about subject knowledge, in particular, need to recognise recent developments because these recommend real-life, engaging and diverse content which reflects the complexities pupils see around them.

Primary beginner teachers, in particular, need to make connections between the teaching skills they are taught and the content and pedagogies which work well in RE. They need to be shown ways of engaging with lived belief and unbelief which resonate with their pupils’ understandings and experiences and promote a more complex understanding of lived religion. They also benefit from explicitly drawing together this understanding of subject knowledge with their developing experience of a range of primary pedagogies.

The Teach: RE Primary course has proved a timely resource for a number of beginner teachers. Early feedback emphasises the engagement and enthusiasm they have for RE when they feel more confident to teach the subject. It is hoped that providers will continue to develop their provision by increasing the hours they devote to RE, with the concomitant emphasis on quality which more time would allow.

References

All Party Parliamentary Group on RE (APPG). (2013). RE: The Truth Unmasked. Retrieved August 7, 2020 from https://www.religiouseducationcouncil.org.uk/resources/documents/religious-education-the-truth-unmasked/.

Aristotle, (350BCE/1999). Nicomachean Ethics Translated by W.D. Ross. Retrieved August 12, 2020 from https://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/nicomachaen.html.

Brine, A., & Chater, M. (2020). How did we get here? The twin narratives. In M. Chater (Ed.), Reforming RE (pp. 21–35). John Catt Educational Ltd: Woodbridge.

Castelli, M., & Chater, M. (Eds.). (2018). We need to talk about religious education. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Chater, M. (Ed.). (2020). Reforming RE. Woodbridge: John Catt Educational Ltd.

Christian Education Movement (CEM). (2016). Understanding Christianity. Retrieved August 16, 2020 from https://www.understandingchristianity.org.uk/.

Clarke, C. & Woodhead, L. (2015) A New Settlement: Religion and belief in schools. London: Westminster Faith debates. Retrieved August 12, 2020 from https://faithdebates.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/A-ew-Settlement-for-Religion-and-Belief-in-schools.pdf.

Clarke, C. & Woodhead, L. (2018). A New Settlement Revised: Religion and belief in schools. London: Westminster Faith debates. Retrieved August 12, 2020 from https://faithdebates.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Clarke-Woodhead-A-New-Settlement-Revised.pdf.

Commission on Religious Education (CORE). (2017). Religious Education for all. Retrieved August 12, 2020 from https://www.commissiononre.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Commission-on-Religious-Education-Interim-Report-2017.pdf.

Commission on Religious Education (CORE). (2018). Religion and Worldviews: the way forward. A national plan for RE. Retrieved August 12, 2020 from https://www.commissiononre.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Final-Report-of-the-Commission-on-RE.pdf.

Conroy, J., Lundie, L., Davis, R., Baumfield, V., Barnes, P., Gallagher, T., et al. (2013). Does religious education work?. London: Bloomsbury.

Dinham, A. and Shaw, M. (2015). RE for REal: the future of teaching and learning about religion and belief. Retrieved August 11, 2020 from https://www.gold.ac.uk/media/documents-by-section/departments/research-centres-and-units/research-units/faiths-and-civil-society/REforREal-web-b.pdf.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2001). Making Social Science Matter: Why social inquiry fails and how it can succeed again,Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Retrieved August 16, 2020 from https://monoskop.org/File:Flyvbjerg_Bent_Making_Social_Science_Matter.pdf.

Freathy, G., Freathy, R., Doney, J., Walshe, K. and Teece, G. (2015). The RE-searchers: A New Approach to Religious Education in Primary Schools. Retrieved August 15, 2020 from https://www.natre.org.uk/uploads/The%2520RE-searchers%2520A%2520New%2520Approach%2520to%2520RE%2520in%2520Primary%2520Schools.pdf.

Freathy, R., & John, H. C. (2019). Worldviews and big ideas: A way forward for religious education? Nordidactica: Journal of Humanities and Social Science Education, 4, 1–27.

Georgiou, G., & Wright, K. (2018). RE-dressing the balance. In M. Castelli & M. Chater (Eds.), We need to talk about religious education (pp. 101–114). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Jackson, R. (1997). Religious education: An interpretive approach. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Kinsella, E. A., & Pitman, A. (Eds.). (2012). Phronesis as professional knowledge: Practical wisdom in the professions. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Kessels, B., & Korthagen, F. (2001). The relationship between theory and practice: Back to the classics. In F. Korthagen, B. Kessels, B. Lagerwerf, & T. Wubbels (Eds.), Linking practice and theory: The pedagogy of realistic teacher education (pp. 20–31). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Kueh, R. (2018). Religious education and the knowledge problem. In M. Castelli & M. Chater (Eds.), We need to talk about religious education (pp. 53–69). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Kueh, R. (2020). Disciplinary hearing: Making the case for the disciplinary in religion and worldviews. In M. Chater (Ed.), Reforming RE (pp. 131–147). John Catt Educational Limited: Woodbridge.

Myatt, M. (2020). Foreword: Reforming RE. In M. Chater (Ed.), Reforming RE (pp. 15–16). John Catt Educational Ltd: Woodbridge.

NATRE. (2013). An analysis of the provision for RE in Primary Schools-Spring Term 2013. Retrieved August 10, 2020 from https://www.natre.org.uk/uploads/Free%2520Resources/2013%2520NATRE%2520survey%2520on%2520RE%2520in%2520primary%2520schools.pdf.

NATRE. (2016). An Analysis of the provision for RE in primary schools. Retrieved August 10, 2020 from https://www.natre.org.uk/uploads/Free%2520Resources/NATRE%2520Primary%2520Survey%25202016%2520final.pdf.

NATRE. (2017). The State of the Nation: A report on religious education provision within secondary schools in England. Retrieved August 15, 2020 from https://www.natre.org.uk/uploads/Free%2520Resources/SOTN%25202017%2520Report%2520web%2520version%2520FINAL.pdf.

NATRE. (2018). An analysis of the provision for RE in primary schools: Autumn term 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2020 from https://www.natre.org.uk/uploads/Free%2520Resources/NATRE%2520Primary%2520Survey%25202018%2520final_1.pdf.

NATRE. (2019a). Primary RE 1000! Retrieved August 10, 2020 from https://www.natre.org.uk/membership/primary-RE-1000.

NATRE. (2019b). What are Ofsted inspectors saying about Religious Education? The first 101 reports that mention RE.Retrieved August 15, 2020 from https://www.natre.org.uk/uploads/Ofsted%2520Primary%2520and%2520Secondary%2520Reports%2520Autumn%25202019%2520221119%2520final%2520final.pdf.

OfSTED. (2007). Making sense of religion. London: Ofsted.

OfSTED. (2010). Transforming religious education. Retrieved August 16, 2020 from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/413157/Religious_education_-_realising_the_potential.pdf.

Ofsted. (2013). Religious education: Realising the potential. Retrieved August 16, 2020 from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/religious-education-realising-the-potential.

Ofsted. (2019a). The education inspection framework. Retrieved August 12, 2020 from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/801429/Education_inspection_framework.pdf.

Ofsted. (2019b). Inspecting the curriculum. Retrieved August 14, 2020 from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/814685/Inspecting_the_curriculum.pdf.

Ofsted. (2020). Initial teacher education (ITE) inspection framework and handbook. Retrieved August 12, 2020 fromhttps://www.gov.uk/government/publications/initial-teacher-education-ite-inspection-framework-and-handbook.

Whitworth, L. (2009). Developing primary student teachers’ understanding and confidence in teaching religious education. In J. Ipgrave, R. Jackson, & K. O’Grady (Eds.), Religious education research through a community of practice: Action research and the interpretive approach (pp. 114–129). Waxmann: Münster.

Whitworth, L. (2017). Engaging Phronesis: Religious Education with Primary Initial Teacher Education students, PhD thesis, Middlesex University.

Woolf Institute. (2015). Living with difference: The report of the Commission on religion and belief in British public life. Retrieved August 8, 2020 from https://www.woolf.cam.ac.uk/research/publications/reports/report-of-the-commission-on-religion-and-belief-in-british-public-life.

Wright, K., Whitworth, L., Lyal, J., Clinton, C., Flanagan, R. & Love, R. (2019a). Teach: RE primary: An introduction. Retrieved August 15, 2020 from https://www.teachre.co.uk/teach-re-course/teachre-primary/.

Wright, K., Whitworth, L., Lyal, J., Clinton, C., Flanagan, R. & Love, R. (2019b). Toolkit for primary religious education ITT providers. Retrieved August 15, 2020 from https://www.teachre.co.uk/itt-providers/primary-itt-tutor-toolkit/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Whitworth, L. Do I know enough to teach RE? Responding to the commission on religious education’s recommendation for primary initial teacher education. j. relig. educ. 68, 345–357 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40839-020-00115-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40839-020-00115-5