Abstract

Weak signals and wild cards are used to scan the environment and make systems more sensitive to emerging changes. In this paper, the applicability of weak signals and wild cards is experimented in a case of a highly reliable and conservative sector, water and sanitation services. The aim is to explore an approach suitable for water utilities. The paper discusses different theoretical and methodological approaches to weak signals and wild cards, and reflects these in relation to the chosen approach. It is argued that the process of weak signals and wild cards can serve as a communication and reflection exercise for an organisation like a water utility. Furthermore, incorporating weak signals and wild cards can be an essential part in futures thinking, challenge prevailing mental models, and make systems more open to sense and learn from their environment. It is recommended for water utilities to apply a loose approach on weak signals and wild cards and embed it as a part of their organisational culture. However, it should be remembered that the approach should always be chosen to match the overall objectives and context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A variety of futures research methodologies exist and are constantly being developed to scan the environment and to make systems more “sensitive to emerging changes as early as possible so that they have better time to react or to be in time to utilize the opportunities of an emerging change.” [1]. The potential of wild cards and especially weak signals in identifying possible changes in the future that could jeopardise or promote a system’s existence have been eagerly discussed and scrutinised [2,3,4,5,6,7].

In this paper we conduct a small experiment on applying a methodology of weak signals and wild cards in the case of water supply and sanitation services.Footnote 1 Weak signals and wild cards have typically been analysed in the context of corporate decision-making or national foresight processes. Water services provide in many ways an interesting and differing case. For example, water utilities function as monopolies in their operational area, and thus in their case utilising weak signals and wild cards are not about finding a competitive edge in the markets, but about sustaining and ensuring safe services.

Our objective is to experiment and analyse the applicability of weak signals and wild cards in a water utility to enhance the futures thinking capabilities, build-up of flexibility, and ability to cope with uncertainties [8, 9]. The basic idea is to see if weak signals and wild cards could be a useful exercise to be practiced without notable additional resources. Thus, this is a small scale experiment instead of a full-fledged foresight process. We discuss different theoretical and practical underpinnings of weak signals and wild cards based on literature, and analyse them against the experience gained in the experiment.

As Popper [10] reminds, methods ought to be chosen according to the objectives and available resources and capabilities [11]. Thus, in the next section we will describe the context of water services and elaborate on our objective.

Water services as a context

In industrialised nations, water services are typically considered highly reliable. People rely on the continuity of these services; they expect to get safe water simply by turning on the tap, and expect wastewater to disappear without harming the environment or human health when flushing the toilet. However, if something goes wrong, it could compromise significantly the well-being of many. One example is the water crisis in the Finnish town of Nokia in the year 2007: some 6000 people were taken ill because treated wastewater was accidentally released into the drinking water distribution system. Another example is the water crisis of City of Flint, Michigan, where residents were exposed to high levels of lead in the drinking water [12]. Thus, if a wild card materialises in water services, the question is not just about business opportunities or threats, but about human lives and functioning societies. Water services support either directly or indirectly all socio-economic activities; during the Nokia water crisis, for example, schools and day care centres had to be closed down and many businesses struggled. On the whole, the Nokia water crisis had a long-lasting socio-economic effect for local businesses.

The water services system can be characterised as a relatively static system. In industrialised countries these systems have mostly been built between the Second World War and the 1980s. During this era, development was expected to be mostly linear. For example, many of the pipelines were scaled for stable growth of consumption, which proved unrealistic after the oil crisis in the 1970s and the introduction of new water saving household appliances. Unfortunately, infrastructure systems are rather inflexible and there has not been significant changes in the systems after the adaptation of centralised drinking water distribution or water based sanitation. There have been improvements to the treatment technologies of both raw water and wastewater, and the materials and technologies used in the piping systems have been improved, but in the end, these changes have not really affected the big picture or the paradigm of water services. Overall, the whole water services system is relatively inflexible and slow to adapt to changing conditions.

The static and inflexible nature of the water systems has contributed to the fact that the sector is rather conservative: somewhat resistant to change and slow to embrace innovations [13]. One reason for this can be related to the fact that water services are considered a natural monopoly. As there has been no need to compete, there has been less need for revolutionary changes and innovations in the field. A further explanation could be the fact that water services are an engineer-oriented sector. As Nafday argues, engineers are generally dismissive of unpredictable events until they occur because engineers are used to focus on specifics and feel uncomfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity [14]. Then again, these characteristics are not limited to engineers alone but can be generalised to all of us. According to Kahneman, people do not cope well with uncertainties but want to believe that by understanding the past it is possible to predict and control the future [15]. In addition, Taleb argues that humans in general focus too narrowly on one’s own field of expertise and overestimate one’s own knowledge [16]. People tend to underestimate the role of chance and the implications of big changes, and overestimate their own capacity to cope with them. To sum up, it is not inherent to organisations in the water services sector - especially those that rely on the bureaucratic organisational culture and construction of the large technical systems - to be adaptive and responsive to changes.

The world has changed and also the operational environment of water services is getting more complex. Various societal changes, such as the development of the information society, have affected the practices of people and organisations. Nowadays, almost everyone has access to inexpensive information and communication channels which, in turn, set new standards for the transparency and openness of organisations. From the point of view of water services, this can be seen either as an opportunity or a threat. It makes organisations more vulnerable if their actions do not meet public expectations but, on the other hand, it can be utilised as a way to better observe and reflect the operational environment.

It is debatable whether the water services sector can maintain its static nature. There are several challenges facing the water services sector compromising its sustainability [13, 17]. In addition to the identified challenges, there might be some less visible but major changes looming around the corner that could seriously impact the field. It has been assessed that future uncertainty is increasing in the infrastructure sector [18]. Furthermore, due to the nature of water services, there are long delays in the feedback loops. Meadows argues that in such cases foresight is essential; if one acts only when a problem is obvious, then one misses a crucial opportunity to solve the problem [19].

For the whole water sector, many foresight activities have been carried out [13, 20] and water issues are also included in some general foresight projects [21]. However, these tend to analyse global situation focussing on the situation in developing countries, and main trends like effects of climate change. Of course these are also relevant for the water services sector and water utilities in Finland, but do not cover all relevant issues and do not really challenge prevailing mental models.

One of our personal motivations to conduct this study was to explore a tool or methodology that challenges current ways of thinking in the field of water services. Water services are too often solely examined from a technical perspective and in isolation from the rest of the society. Due to the conservative nature of the sector, current ways of thinking and modus operandi are rarely confronted. However, from a systems perspective, water services are entangled with and bound within wider sociotechnical, political, cultural and economic complexes [22, 23]. We, in the field of water services, need to be more sensitive to what is happening elsewhere in society and take this into consideration in strategic planning. As Hiltunen argues weak signals can help us to break prevailing mental models, encourage us to think differently, and help us to be more innovative about the futures [1].

Because of our aspiration to challenge prevailing mental models and the conservative character of water services sector, and our interest in systems view, our approach is more inclined to that of critical futures studies than on the strong empiricist and technical orientation of foresight activities [9, 24, 25], and this will also guide our methodological choices that are discussed in the next section.

Methodological framework

This section first of all covers a short overview of theory on weak signals and wild cards, and methodology related to them. At the end, the material choice of this study is introduced.

Weak signals

Igor Ansoff, who can be considered the pioneer of weak signals analysis, defines weak signals as imprecise early warnings about impeding impactful events [26]. Weak signals are too incomplete to permit an accurate estimation of their impact, and/or to determine a complete response [4, 27]. There are, however, many views on weak signals some of which are contradictory [3, 28]. For example, some use the terms ‘emerging issues’, ‘seeds of change’, ‘wild cards’ and ‘early warning signals’ interchangeably with weak signals, whereas others make a clear distinction between these terms [1]. According to Moijanen, weak signals are generally defined in three ways [28]: First, some consider that weak signal in itself is a changing phenomenon that will strengthen in the future. Second, some see that weak signals are the cause of new phenomena and changes. Third, some limit weak signals as symptoms or signs that indicate change in the future.

Another issue causing confusion in defining weak signals is the debate on their objectivity versus subjectivity; or the essentialist or deterministic versus the constructivist perspective [2, 3, 7]. According to the objective view, weak signals exist as such and are independent of the interpreter. Then again, according to the subjective view, weak signals always need a recipient who interprets the signal [28]. Rossel criticises existing literature on weak signals for “neutralising” weak signals, “as if they were objects or features in their own right, waiting to be discovered, instead of considering them as the expression of the paradigmatic capacity of the analyst to organise perception and interpretation in a certain way” [11]. Following the subjective view, interpretation of weak signals depends on the context and is situated [4, 5]. Thus, same signal can in one case be interpreted as weak and in another as strong.

Wild cards

Wild cards have been part of futures research and scenario building since the 1960s. However, it was only in 1996 that an approach to study wild cards came about as John L. Petersen’s book Out of the Blue: How to Anticipate Big Future Surprises was published. [29]. Wild cards are generally defined as rapid, surprising events with huge disastrous, destructive, catastrophic or anomalous consequences. It should not be forgotten, however, that wild cards can also be beneficial events, whose potential we want to be able to exploit. Usually these events take place so rapidly that normal, planned management processes cannot respond, making the organisations highly vulnerable [27, 30, 31]. Petersen and Steinmüller argue that in the complex and interconnected world of today, it is now more relevant than ever to study wild cards so that we could prepare for them, prevent them or in some cases even deliberately provoke them [29]. Furthermore, wild cards can be seen as a heuristic to articulate uncertainty [32].

Some use wild cards as a synonym for weak signals. Hiltunen however, defines wild cards as events with a huge impact whereas weak signals are signs of events or emerging issues, such as wild cards [1]. Whether or not one considers these two terms as synonyms, depends on how one defines weak signals. If one accepts that weak signals can be both events and signs of events, then wild cards and weak signals can be used interchangeably. However, if one maintains that weak signals are not events in themselves but indications of them, wild cards and weak signals are not synonyms. Instead, it can be perceived that weak signals precede wild cards. Thus, weak signals can be employed as a means to anticipate wild cards [1, 30].

Wild cards are often confused with gradual change [1]. Gradual change, like the change from dry toilets to water closets, has a significant impact, but it is not rapid as it is not possible to observe the change and adapt to it. In the case of wild cards, there is only little time to react before change takes place. An example of a wild card could be the Nokia water crisis described in the introduction.

There is some disagreement whether a wild card can be anticipated at all. Petersen and Steinmüller distinguish three types of wild cards: 1) events that are known and relatively certain to occur but without any certainty as to timing (e.g. the next earthquake), 2) future events that are unknown to the general public (or even the professionals) but that could be discovered if we only consulted the right experts or if we had adequate models (e.g. impacts of climate change), and 3) intrinsically unknowable future events that no expert has in mind, where we lack concepts and means of observation (the unknown unknowns). The last type of wild cards, the unknown unknowns can only be judged by hindsight [29].

Mendonça et al. [30] argue that it is sometimes possible to anticipate wild cards in advance as weak signals of it are available. The question is if someone notices these signals and is able to make “correct” interpretations. In the case of the Nokia water crisis the weak signals were observations made by consumers reporting on changes in the appearance of the drinking water. Consumers complained about these to the water utility, but these complaints, or weak signals, were not taken seriously. The Nokia water utility assumed that foaming of the tap water and its weird smell and taste were due to pressure changes in the water distribution network. It was only after two days when people reported stomach problems that the issue was taken seriously.Footnote 2 If the weak signals had been taken seriously and reacted earlier on, it probably would have been possible to limit the extent of the water epidemic.

Methodology

In general, the methodology of weak signals and wild cards is part of the process of horizon or environmental scanning [10, 27, 34], and as such, it situates in the interpretative domain [9]. It is qualitative in nature and relies on subjective and creative analysis [10]. Popper maintains that the methodology is undeveloped, and there are calls for more rigorous processes [35]. Some methods to analyse weak signals have been developed. For example, Ansoff has created a Weak Signal Issue Management System (Weak Signal SIM). Hiltunen argues that the practical use of Ansoff’s approach appears to be very mechanistic as there is no space for creativity and intuition [1].

According to Schultz, a basic approach to scan environment for weak signals consists of the following phases [36]: 1) choosing from five to nine information sources, that should preferably be from different sectors and should cover both, specialist and fringe sources, 2) creating a scanning database, including the title, source, description and implications of the signal, 3) evaluating scan “hits”: are they subjectively or objectively new, are they confirming, reinforcing or negating, and 5) looking for interdependencies, feedback delays and repeating patterns in the scanned data [31, 37].

As weak signals are seen to precede or indicate wild cards, identifying weak signals and interpreting them can produce information on wild cards [38]. Another possibility is to directly try to identify wild cards and then assess and monitor them by identifying weak signals that could indicate these wild cards. For example, Petersen and Steinmüller introduce a wild cards methodology that starts by directly identifying wild cards [29]. This can be done by using published lists of wild cards.Footnote 3 However, they recommend collecting or inventing wild cards specific to case in question. This can be done by, for example, brainstorming, science fictioning and genius forecasting [10]. The identified wild cards are assessed and their amount is narrowed down so that only the ones deemed most relevant will be considered in the following phases. The third phase consists of monitoring weak signals of the wild card. In the fourth phase, options for action (to prevent, to prepare for, or to promote wild cards) are discussed.

Usually, identification and analysis of weak signals and wild cards is conducted by a group of highly-skilled people with expertise and creativity [10]. Text-mining tools and search engines can be used to detect signals from a vast amount of data. One key question in the process, is the choice of sources to search for signals. Hiltunen [39] conducted a survey study asking futurists what they consider to be good sources of weak signals. According to the results, personal connections are emphasised, and overall, favoured sources are researchers, futurists, colleagues, academic and scientific journals, and reports of research institutes.

As is obvious from the preceding discussion, there is a variety of ways to understand and conduct studies focused on weak signals and wild cards. We will next describe the approach we applied in our exercise.

Approach in this study

The method we used in this study does not directly follow any of the approaches described in literature. Weak signal methods are often used as a part of national foresight processes. Our case, however, was somewhat different. We were not looking to create scenarios or strategies or to formulate policies for the whole water service sector. Our objective was to conduct a small scale experiment on weak signals and wild cards to see, if they could be applied in water utilities. Thus, the starting point was that the process should be possible to be embedded in daily practices and on routine basis, and that it would not necessitate special resources.

We started by discussing the possible problems and issues related to water services. Following Coffman [40], we were discussing about things that just feel funny about our case and things that we see as happening, but cannot really pin them down. In a sense, this phase resembles also the first phase of wild cards methodology: inventing things that could happen [29]. Next, we decided on the sources or the material that we go through to look for weak signals.

As mentioned, preferred sources for horizon scanning are usually researchers and experts and their publications. However, as discussed in the introduction, the water sector is rather conservative. Thus, we felt that it would not be beneficial to use field experts or their writings as a source. Furthermore, the idea was try to use sources that would be readily available and accessible to people working in the water utilities. Thus we chose newspaper and magazine articles that were not related to water sector directly as our source material. In addition, we used some other materials, like blog texts. These were used in the first phase when we were trying to scan for interesting issues and problems external to the water sector. Hiltunen also recommends the use of so called peripheral sources (such as arts, science fiction, alternative press, blogs) [39].

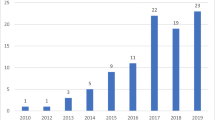

We decided to cover a time span of one year for the newspapers and magazines (March 2010 – March 2011). The newspapers chosen were Aamulehti and Lapin Kansa. We did not read all the issues published during the particular year, but made a selection and focused on papers of 11th and 27th day of each month. Aamulehti is the newspaper in the Tampere area and Lapin Kansa is published in northern Finland. Magazines chosen were Image and Kuluttaja. Image magazine covers a wide range of phenomena from popular culture to politics, and it can be characterized as a trendsetter. We chose Image as we thought it might offer some fresh perspectives. Kuluttaja magazine is published by the Finnish Consumer Agency and it focuses on reviews of products and services. Kuluttaja was chosen to give perspectives of changes in consumer culture and preferences of people.

After the choice of sources, we read through the material and made notes of everything novel and unexpected that sparked our imagination. After the scanning phase, we discussed our findings and interpretations, and clustered them into themes.

Findings

As described, we started the empirical part of this study by discussing things that feel funny about water services and things that are happening, but we cannot really pin them down. Second, we read the newspapers and magazines. The results are shortly described in this section.

Inventing things that could happen

First, we discussed some potentially emerging issues in the water services sector. Basically, these were issues that had puzzled us already before. One such issue is bottled water. Many water sector experts condemn bottled water as a totally useless, ridiculous and stupid product and downplay people’s reasons to choose bottler water over tap water. The markets for bottled water, however, have been rapidly growing so consumers are appealed to it. Then again, the biggest challenge in Finnish water services sector is the aging infrastructure and the growing renovation debt [17]. If the water utilities cannot keep up with the needed infrastructure renovation pace because of lack of required resources, the quality of tap water will be endangered at some point. Could one option be to accept lowered quality of tap water and use bottled water for drinking and other purposes requiring higher quality of water? After all, about 95% of tap water is used for other than drinking and cooking purposes, such as flushing toilets.

Another issue discussed was water-related crises – will there be another crisis like the one in Nokia? What could trigger such a crisis? Could one cause be the use of various plastic compounds in the distribution networks, such as new epoxy plastics in renovation? There is no experience of these materials in the long-term. There have, however, been concerns about the plastic used to package bottled water, and studies showing that more or less hazardous chemicals can be released from the plastic into water [41]. Could plastic water pipes jeopardise people’s health in the future? Why would plastic be harmful only as bottle material but not as pipe material? Also, what if it is found out that the plastic pipes are not durable in use and need to be replaced only after few years in use? This would not necessarily compromise people’s health directly, but would be a huge financial burden to the water service providers and, after all, to the customers.

The third issue was the role of the customer in water services. In Finland, provision of water services is the responsibility of municipalities. Is there a tension between the roles of a customer and citizen? Will people trust public services in the future? Will the requirements of people significantly change in the future? Quite many water service experts seem to think that many challenges of the field could be resolved by moving water services further away from political decision-making, i.e. especially that water works would be financially separate from the municipal administration. How will this impact water services and people’s perception of these services?

Scanning for weak signals and wild cards

Table 1 presents a selection of signals that resulted from reading the newspaper and magazine articles. Altogether around hundred notes were made, but the table presents only the ones that we focused in our analysis and grouped into clusters. Furthermore, what is obvious is that the signals are difficult to present without interpretation. Thus, we will next discuss our interpretation of these signals in relation to water services sector.

One issue that seemed to rise from reading the newspaper and magazine articles were customers’ changing expectations. Both public and private services need to be convenient and readily available. Older generations are used to being passive objects or recipients of services, but younger generations want to make more individual choices about services and want services to reflect their personal values and needs. One aspect related was the need to focus more on the ultimate purpose of services, and trying to find out and anticipate what people actually want of the services. An individual and his or her needs should be the starting point of different public services, not the way these services are organised or minimising their costs.

Another issue is the apprehension about chemicals and the appreciation of naturalness. This was especially visible in the Kuluttaja magazine’s test on consumer products. People expect more information about chemical consistency and additives of different products in an understandable way. Some businesses had already responded to these demands. An example of this is a full-page advertisement by a dairy producer on new margarine that is “totally without additives”.

The third issue that we found interesting was related to political decision-making. There were some articles about how power has been shifted away from democratically chosen political decision-makers to professional civil servants. For example, in Image 8/2010 the victory of an Icelandic political party that was set-up just as a joke was explained by voters’ frustration towards the toothless political decision-making in the past. In general, there were calls for politicians to resume power and carry their responsibility, not hiding anymore behind civil servants. There were quite a few articles that called for more open, transparent and participatory decision-making processes.

There were also some examples of how decision-making processes had been improved. The civil servants responsible for urban planning and waste management in the town of Rovaniemi, Finland, for example, participate in open coffee meetings with local residents. In these unofficial gatherings people feel easier to ask civil servants about things puzzling them and sharing their personal views. Another issue, quite expectedly, was the utilisation of internet and social media in public services. Quite surprising, however, was that the Finnish tax authorities turned out to be forerunners and are already utilising blogs and discussion forums in their work.

All in all, it might be useful to think about how the service could be made more customer-oriented in the water services sector. One should also think about what the ultimate purpose of the service is. This is also related to the trend of more open, political and transparent decision-making. If politicians assumed more power and responsibility over their decisions, how would this impact the water services sector? Would the resources to provide safe service be improved? What if customers and citizens would be better aware of decision-making related to water services? Would this increase or decrease resources?

These are just a few examples of the issues that were chosen and analysed. In the next section, these findings are assessed against theories on weak signals and wild cards.

Discussion

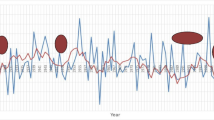

One problem assessing weak signals is, as Hiltunen points out, that the actual value or worth of weak signals can only be judged with hindsight [1]. The same can be said to apply to wild cards. We scanned for the weak signals and wild cards in year 2011. Now, after six years we can say that there is no clear indication that customers’ changing expectations or changing political processes would have had major implications for the Finnish water sector. Then again, the apprehensions about chemicals seems to be a trending topic in the water sector. For example, the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health together with the Ministry of Environment stated in their press release that certain plastic water pipes had been found to cause taste and odour problems with tap water.Footnote 4 This was reported also in the news and raised some discussion in social media (e.g. blogs). Still, we cannot know if our interpretations are correct or useful to the water services sector. Furthermore, we cannot rule out false positives (discovering later on that the evidence was misleading) and false negatives (being right but on false grounds) even in hindsight [5].

According to Rossel, we should not only focus on the signals themselves but the process [11]. We should ask how and why we chose signals and interpreted them in a certain way. Thus, we will discuss our findings against theories on weak signals and wild cards. First of all, the reliability of findings depends on the resources or materials used. According to Hiltunen [1] weak signals can be divided into primary and secondary exosignals. Primary signals are directly connected to an emerging issue and are, for example, visual observations of it. When primary signals are interpreted and presented e.g. in newspapers, they turn into secondary signals. Hiltunen [1] warns that there is a risk with secondary signals being distorted or even fictitious. Probably one of the biggest weaknesses in this study was the sources we chose. We used mainly newspapers and magazines, and thus it can be said that we relied only on secondary signals.

A further weakness with the materials used in systematic scanning was that none of them were really peripheral or alternative as recommended [39], but they were mainstream. In the background, identifying the emergent issues, we did use blog writings but these were not used in the systemic scanning. The original idea was to include also peripheral sources for scanning, but this was given up due to lack of time.

Then again, as the futurists in Hiltunen’s study emphasised, it is not the sources of weak signals that are important, but rather the processing of them [39]. Thus, the actual process will be discussed next. As mentioned, we started by discussing issues that had puzzled us. According to van der Heijden, people have tacit knowledge consisting of isolated observations and experience that they have not yet been able to integrate with their codified knowledge and this is also why they do not understand meaning of these very clearly [42]. Furthermore, he describes weak signals as unconnected insights and knowledge. It could be said that our first discussions on the problems and issues was an attempt to try to understand the weak signals we had encountered earlier on. Now, afterwards trying to separate the signals from the interpretations of the emerging issues they are signalling, is quite impossible and would be artificial.

Similarly, if one looks at the findings described in the previous section, they are not descriptions of the signals themselves but clusters of signals and their interpretations. This relates to the debate whether weak signals can be objective, and whether the signal can be separated from its interpretation. It was obvious in the process, that nearly all of the signals we found were somehow related to the problems we had discussed earlier on. One could accuse us of scanning for signals that further strengthen our previous understanding. Hiltunen describes this as “collective blindness”, when only signals that strengthen a vision are allowed inside an organisation [1]. She argues that this can happen easily with secondary exosignals. However, starting with a problem or issue in mind, is also part of many methodologies described in the literature [29, 37].

Interpretation, in our case, was mainly based on assessing the relevance of signals in the water services sector. Hiltunen warns of emphasising the relevance too much as it can cause filtering especially of signals that are inconvenient but could have a big impact in the future [1]. Then again, it can be argued that weak signals reach our consciousness because we intuit that they have some relevance to our situation [4, 42]. It is a tempting idea that we could scan our environment without preconceptions. However, in practice this is not possible. Instead, we agree with Rossel who argues that we should make “our assumptions as explicit as possible, and part of the weak signal identification process itself (i.e. taking into account the different usages we have of weak signals, according to our diverse roles and contextual interests)” [11]. The first part of the results, describing the issues that puzzled us, is an attempt to make our assumptions explicit.

Another issue that could probably have improved the results by helping to avoid the filtering (e.g. past experiences, educational background, political interests [4]) to some extent would have been to include more people in the process with more diverse backgrounds [43]. If their preconceptions, assumptions and tacit knowledge is diverse, diversity of the results would probably be enhanced. The futurists in Hiltunen’s study emphasised interaction, openness and discussion in finding weak signals [39]. Or as Mendonça et al. state, the process is actually structured networked communication [4]. In addition, it would be important to pay more attention the design of the frame of interpretation [44].

One could criticise our approach as being too loose, as we lacked an explicit frame on interpretation. Furthermore, Moijanen argues that scanning for weak signals requires systematic search as one must be able to distinguish weak signals from the background noise [28]. Also Holopainen and Toivonen criticise the loose use of the concept of weak signals as it blurs the identification of the really relevant and strategic changes [3]. However as Mendonça et al. remind, the distinction between noise and signal is not so straightforward but depends on the interpretive context [4].

Furthermore, in our view, a too mechanistic and rigid approach would probably limit the findings and kill the creativity of the process. Furthermore, it is very probable that we would have found answers to or at least reinforced problems that we are already aware of rather than challenging our understanding of problems. The whole idea, after all, is to try to break mental models and come up with events that you would not have thought about otherwise. It can also be argued that a more loose approach would not create false sense of security and certainty so easily [16]. A very rigid and heavy approach, on the other hand, can create the illusion that the operational environment is under control and weak signals and wild cards are being managed. Actually, Mendonça et al. maintain that thinking about weak signals can help to acknowledge the limits of foresight abilities [4].

Our interpretations and analysis were mostly based on analogies, i.e. scanning for signals from other sectors and analysing what these could mean in the water services sector. This kind of approach is criticised by van der Heijden [42]. He argues that the validity of such analogies cannot be assessed and thus, it must be concluded that the resulting subjective probabilities are untestable, arbitrary and meaningless. However, Ruuttas-Küttim encourages combining different contexts to weak signals in order to see their real potential [1].

Furthermore, it is questionable whether our findings really count as weak signals or wild cards. For example, the issue with the possible chemical contamination of tap water from the plastic pipes is more likely a gradual change than a wild card, as it is not a rapid development and water works could monitor this and change their behaviour in case some concerning results would appear [12]. Most of the other issues we discussed are also more gradual than rapid in nature. Thus, it could be said that we were not able to recognise actual wild cards. However, it needs to be remembered that it is also important to monitor weak signals for gradual change. As Hiltunen points out, people tend to ignore weak signals indicating gradual change [31].

Moreover, one could say that our weak signals are not signals but more like trends. This is due to the fact that they are presented in combination with the interpretations and they have been clustered together. Hiltunen actually reminds us that the single weak signals do not tell us much about futures, but a number of weak signals might tell us something about emerging trends in the future. She argues, thus, that weak signals should be clustered to trends [1].

It is debatable, whether the signals we found could be considered as weak. This again is related to our choice of materials and methodology. According to Hiltunen, a key characteristic of weak signal is its’ low visibility, as it usually appears only in a single channel and locally [1]. Our sources, newspapers and magazines, are quite widely read and their visibility is not limited. Another criteria proposed to describe the “weakness” of signals refers to the inability to give meaning to them [42]. In comparison, “strong” signals would be such that we can clearly understand the potential implication. Based on this definition our findings could be characterised as weak signals. They can be considered to be strong signals in their original context, but when they are transferred to the context of water services sector their implications are not clear and thus, they can be said to represent weak signals [38]. Innovativeness of findings always depends on the context [45, 46].

Several authors seem to favour validation of found signals through cross-referencing with published research or panel discussions or workshops with experts [13, 27]. We did not conduct a systematic validation of our findings as we find it debatable whether we can actually validate weak signals. As stated in the beginning of this section, weak signals and wild cards can only be fully validated in the hindsight. Furthermore, are the signals really novel and unexpected if they can be easily verified? We applied Hiltunen’s informal test of weak signals that is based on the reactions of colleagues [1]. According to Hiltunen, if your colleagues oppose a signal or it is not really talked about (taboo) it can be considered a weak signal. We presented the idea of bottled water replacing drinking water from the tap to our colleagues. First, there was a long silence which was followed by declarations of the stupidity of the whole idea. It seemed that our colleagues were upset by the sheer idea of taking bottled water seriously. This reinforced our idea that it would be important to expose our sector to thinking in new ways and breaking conservative mental models to better prepare, prevent or take advantage of these events in the future.

According to Holopainen and Toivonen, Hiltunen’s criteria is highly subjective [3]. Once again, discussion is reverted on the objectivity and subjectivity of the weak signals, and the problems of assessing signals beforehand. Weak signals and wild cards are partly evidence-based, but at the same time also results of imagination, thinking and debating [27]. In the end, we argue that the “rightness” or “correctness” of the weak signals and wild cards is secondary and the primary importance is in the process itself. Studying theories on weak signals and wild cards, scanning the sources for them and analysing our findings helped us to attune our senses to signals from outside the water sector and to acknowledge the limits of knowing about the future. Following Mendonça et al., we maintain that the value lies in the potential for social and organisational learning [4]: building capability to deal with uncertainties, the unknowns and the unexpected [see also 33]. This is an on-going process and “preparing for future unknowns is always an unfinished business” [4]. Thus, horizon scanning should be undertaken on routine basis to uncover and challenge conventional and deep-rooted mental models [34].

However, we are not suggesting that presented loose approach to weak signals and wild cards should be applied everywhere, or that it could replace more focused and extensive foresight activities in organisations [47]. If the aim is to formulate policies or strategies on the basis of findings, a more thorough and extensive process, preferably combined with other methods would be recommendable [10].

Conclusions and recommendations

As was discussed, it is debatable whether any of the “signals” we discovered were really weak signals by scientific criteria. Similarly, we were not able to identify wild cards. Furthermore, our approach did not follow any strict methodology but was quite loose. We cannot, at least yet, show that our findings would be “correct” as weak signals and wild cards can only be judged with hindsight. However, we do not think that this exercise was useless but quite the contrary. We have presented some of our findings to other people in the water services sector. Reactions have ranged from ignorance to anger. We argue that scanning for weak signals and wild cards can help one to step out of one’s comfort zone and think also about inconvenient issues [45]. Even if the weak signals and wild cards would not materialise in the future, it is useful to challenge oneself to think differently. This small experiment, for example, has moulded our research interests and encouraged new ways of looking at challenges of water services.

Sustainability of water services is a key issue for the well-being of people. The world becomes increasingly complex, unpredictable and uncertain, and this will eventually impact also the water services sector increasingly. As the sector is static and conservative, it is not very agile to react to these changes. This makes the need for strategic thinking and planning even more evident. The idea of weak signals and wild cards can play an important part in this [48].

Water services, by their nature, strive for keeping balance; a lot of effort is put to ensure that nothing unwanted occurs. In this regard, it is a sort of crisis management long before any crisis takes place. Thus, as Edwards argues [49], vigilant organisations capable of social learning succeed well in avoiding crises and accidents, even if their operations are heavily based on technologies [50]. More theoretically speaking, exploring weak signals and wild cards can serve as a communication and reflection practice in which new information is processed, thereby producing and decreasing entropy in the social system. Organisation’s ability to continuously produce and decrease entropy can ensure its autopoietic process by which an organisation can evolve over time [51]. We therefore see that weak signals and wild cards are useful methods for improving vigilance and learning in the organisations of the water services sector.

Thus, we recommend water utilities and other central actors in the field of water services to apply a loose approach on weak signals and wild cards as a part of their organisational culture. We see this more as an ongoing activity and future-oriented organisational philosophy rather than a strict scientific exercise [25]. If the aim is to use the results for policy or strategy formulation, then a more extensive process utilising futurist and foresight expertise should be considered.

In practice, loose process to uncover weak signals and wild cards in water utilities could, for example, simply be a coffee table discussion covering daily newspapers and some social media sources, reflecting what these could mean for the water services and trying to identify relations between the potentially meaningful signals. Reflexivity should be an important part of the process, i.e. discussing why and how certain interpretations have been made. Based on our experiment and literature, we argue that this would help to build a dynamic, learning organisation that is open to sense the environment around it.

Notes

We will use the term “water services” to cover both water supply and sanitation services from here onwards.

For a detailed description of the Nokia Water Crisis see [33].

See e.g. http://wiwe.iknowfutures.eu/

Ministry of the Environment (2014) Uusista muovisista vesijohdoista aiheutunut paikoin haju- ja makuhaittoja talousveteen. http://www.ym.fi/fi-FI/Ajankohtaista/Tiedotepalvelu/Uusista_muovisista_vesijohdoista_aiheutu(30347). Accessed 22 February 2017.

References

Hiltunen E (2010) Weak signals in organizational futures learning. Aalto University School of Economics, Dissertation

Miller R, Rossel P, Jorgensen U (2012) Future studies and weak signals: a critical survey. Futures 44:195–197. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2011.10.001

Holopainen M, Toivonen M (2012) Weak signals: Ansoff today. Futures 44:198–205. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2011.10.002

Mendonça S, Cardoso G, Caraça J (2012) The strategic strength of weak signal analysis. Futures 44:218–228. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2011.10.004

Rossel P (2012) Early detection, warnings, weak signals and seeds of change: a turbulent domain of futures studies. Futures 44:229–239. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2011.10.005

Saritas O, Smith JE (2011) The big picture – trends, drivers, wild cards, discontinuities and weak signals. Futures 43:292–312. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2010.11.007

Cevolini A (2016) The strongness of weak signals: self-reference and paradox in anticipatory systems. Eur J Futures res 4:1–13. doi:10.1007/s40309-016-0085-1

Ansoff HI (1975) Managing strategic surprise by response to weak signals. California Management Review 18:21–33

Slaughter RA (1999) A new framework for environmental scanning. Foresight 1:441–451

Popper R (2008) Foresight methodology. In: Georghiou L, Harper JC, Keenan M, Miles I, Popper R (eds) The Handbook of technology foresight: concepts and practice. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 44–88

Rossel P (2009) Weak signals as a flexible framing space for enhanced management and decision making. Technol Anal Strateg 21:307–320. doi:10.1080/09537320902750616

Pieper KJ, Tang M, Edwards MA (2017) Flint water crisis caused by interrupted corrosion control: investigating "ground zero" home. Environmental Science & Technology 51:2007

Saritas O, Proskuryakova L (2017) Water resources – an analysis of trends, weak signals and wild cards with implications for Russia. Foresight 19:152–173. doi:10.1108/FS-07-2016-0033

Nafday AM (2009) Strategies for managing the consequences of black swan events. Leader Manag Eng 9:191–197. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)LM.1943-5630.0000036

Kahneman D (2011) Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York

Taleb NN (2007) The black swan: the impact of the highly improbable. Random House, New York

Heino OA, Takala AJ, Katko TS (2011) Challenges to Finnish water and wastewater services in the next 20–30 years. E-Water 01:1–20

Dominguez D (2008) Handling future uncertainty - strategic planning for the infrastructure sector. Dissertation, ETH Zurich

Meadows DH, Wright D (2008) Thinking in systems: a primer. Chelsea Green, White River Junction

Rognerud I, Fonseca C, Kerk A van der, Moriarty P (2016) IRC trends analysis, 2016–2025

Ravetz J, Miles I, Popper R (2011) ERA toolkit: applications of wild cards and weak signals to the grand challenges & thematic priorities of the European research area, Manchester Institute of Innovation Research, University of Manchester.

Swyngedouw E (2004) Social power and the urbanization of water: flows of power. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Castro JE (2009) Systemic conditions and public policy in the water and sanitation sector. In: Castro JE, Heller L (eds) Water and sanitation services. Earthscan, London, pp 19–37

Slaughter RA (2002) From forecasting and scenarios to social construction: changing methodological paradigms in futures studies. Foresight 4:26–31

Miles I, Harper JC, Georghiou L, Keenan M, Popper R (2008) The many faces of foresight. In: Georghiou L, Harper JC, Keenan M, Miles I, Popper R (eds) The Handbook of technology foresight: concepts and practice. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 3–23

Ansoff HI (1984) Implanting strategic management. Prentice/Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Amanatidou E, Butter M, Carabias V, Könnölä T, Leis M, Saritas O, Schaper-Rinkel P, van Rij V (2012) On concepts and methods in horizon scanning: lessons from initiating policy dialogues on emerging issues. Science and Public Policy 39:208–221. doi:10.1093/scipol/scs017

Moijanen M (2003) Heikot signaalit tulevaisuuden tutkimuksessa. (Weak signals in futures studies). Futura 4:38–60

Petersen JL, Steinmüller K (2009) Wild cards. In: Glenn JC, Gordon TJ (eds) Futures research methodology version 3.0. The millennium project, Washington DC

Mendonça S, Cunha EMP, Kaivo-oja J, Ruff F (2004) Wild cards, weak signals and organisational improvisation. Futures 36:201–218. doi:10.1016/S0016-3287(03)00148-4

Hiltunen E (2006) Was it a wild card or just our blindness to gradual change? J Futures Stud 11(2):61–74. doi:10.6531/JFS

Nikolova B (2017) The wild card event: discursive, epistemic and practical aspects of uncertainty being ‘tamed’. Time Soc 26:52–69

Seeck H, Lavento H, Hakala S (2008) Kriisijohtaminen ja viestintä: tapaus Nokian vesikriisi. Helsinki, Suomen kuntaliitto

Miles I, Saritas O (2012) The depth of the horizon: searching, scanning and widening horizons. Foresight 14:530–545

Popper R (2008) How are foresight methods selected?. Foresight 10:62-89l.

Schultz WL (2002) Environmental Scanning: a Holistic Approach to Identifying and Assessing Weak Signals of Change. http://www.infinitefutures.com/essays/prez/holescan/sld001.htm. Accessed 21 Feb 2017

Linturi H (2003) Heikkoja Signaaleja metsästämässä. http://nexusdelfix.internetix.fi/en/sisalto/materiaalit/2_metodit/3_signalix?C:D=61590&C:selres=61590. Accessed 22 Feb 2017

Hiltunen E (2008) The future sign and its three dimensions. Futures 40:247–260. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2007.08.021

Hiltunen E (2008) Good sources of weak signals: a global study of where futurists look for weak signals. J Futures Stud 12(4):21–44

Coffman B (1997) Weak signal research. Part I: Introduction. http://www.mgtaylor.com/mgtaylor/jotm/winter97/wsrintro.htm. Accessed 22 Feb 2017

Westerhoff P, Prapaipong P, Shock E, Hillaireau A (2008) Antimony leaching from polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic used for bottled drinking water. Water Research 42:551–556. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2007.07.048

Van der Heijden K (1997) Scenarios, strategies and the strategy process. Nyenrode University Press, Nyenrode

Schatzmann J, Schäfer R, Eichelbaum F (2013) Foresight 2.0 - definition, overview & evaluation. Eur J Futures res 1:1–15. doi:10.1007/s40309-013-0015-4

Jørgensen U (2012) Design junctions: spaces and situations that frame weak signals – the example of hygiene and hospital planning. Futures 44:240–247. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2011.10.006

Miles I, Harper JC, Georghiou L, Keenan M, Popper R (2008) New Frontiers: emerging foresight. In: Georghiou L, Harper JC, Keenan M, Miles I, Popper R (eds) The Handbook of technology foresight: concepts and practice. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 400–417

Georghiou L, Keenan M (2008) Evaluation and impact of foresight. In: Georghiou L, Harper JC, Keenan M, Miles I, Popper R (eds) The Handbook of technology foresight: concepts and practice. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 376–399

van Rij V (2010) Joint horizon scanning: identifying common strategic choices and questions for knowledge. Science and Public Policy 37:7–18

Hauptman A, Hoppe M, Raban Y (2015) Wild cards in transport. European Journal of Futures Research 3:1–24. doi:10.1007/s40309-015-0066-9

Edwards PN (2003) Infrastructure and modernity: force, time, and social organization. In the history of sociotechnical systems. In: Misa T, Brey P, Feenberg A (eds) Modernity and technology. MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 185–226

Starbuck WH (2017) Organizational learning and unlearning. The Learning Organization 24:30–38. doi:10.1108/TLO-11-2016-0073

Maturana HR, Varela FJ (1980) Autopoiesis and cognition—the realization of the living. Reidel Publishing Company, Dordrecht

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the Alfred Kordelin Foundation is gratefully acknowledged. Furthermore, we would like to express our gratitude for the three anonymous reviewers whose comments and suggestions significantly improved the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Takala, A., Heino, O. Weak signals and wild cards in water and sanitation services – exploring an approach for water utilities. Eur J Futures Res 5, 4 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40309-017-0111-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40309-017-0111-y