Abstract

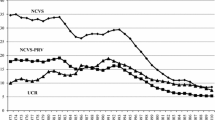

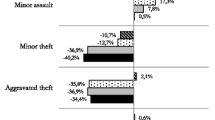

The study intends to explain the convergence of the UCR and NCVS data series (1973–2008). Hypothesized explanatory variables include increased police productivity, change in people’s attitudes toward crime and the police, demographic changes, changes in the measurements used in data collections, and the advancement of telecommunication tools. The time series models with relevant predictor variables are estimated to explain the convergence of the two crime data series in five different crime categories. The results show that an increase in the total number of employees in the police, changes in measurements, especially the methodological changes adopted in the victimization survey in 1992, and changing attitudes toward crime and the police affect the relationship between the two crime data series and may have helped the convergence of the two. We argue that (1) the convergence of the two crime data series is not a mere convergence of methodological inadequacies resulting from the declining quality of the victimization survey and (2) all the predictor variables only partially affect the convergence of the two crime data series. Methodological limitations of this study are also addressed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The UCR started an incident-based ambitious data collection program in 1987, known as the National Incident-Based Reporting Systems (NIBRS). The NIBRS collects crime data on 46 different offenses classified in 22 offense categories known as group A and arrest data for 11 offenses categories known as group B. The expansion of the NIBRS is slow because of its ambitious nature and the need for resources and technical expertise. However, 6444 law enforcement agencies from 31 states are participating in the NIBRS (FBI, 2004).

A lengthy introduction of the historical and technical details concerning the UCR and NCVS is not provided here given the space constraints and focus of the paper. Technical notes for the UCR and NCVS should be consulted for detailed descriptions of the respective crime data series. In addition, Biderman et al. (1991) and various chapters in Lynch and Addington (2007) provide exhaustive coverage on many aspects concerning these two crime data.

In the UCR, rape is defined as “the carnal knowledge of a female forcibly and against her will” while the NCVS includes rape of both female and male. The basic counting unit of the NCVS is the victim, and the basic counting unit of the UCR is the offense.

Hotel and hierarchy rules are counting protocols in the UCR. According to the hotel rule for scoring, if a number of dwelling units under a single manager are burglarized and the offenses are more likely to be reported to the police by the manager rather than the individual tenants, the burglary must be scored as one offense (Federal Bureau of Investigation 2004). According to the classifying and scoring rule of hierarchy, law enforcement agencies are required to identify and report the most serious crime in a multiple-offense situation in which several offenses have been committed at the same time and place. The hierarchy rule does not affect the prosecution. The offenses of justifiable homicide, motor vehicle theft, and arson are exceptions to the hierarchy rule (Federal Bureau of Investigation 2004).

The police productivity hypothesis (O’Brien 1999) argues that the convergence of the two crime data series was largely, at least in the initial years, facilitated by the increase in the UCR rates and the increase in the UCR rates was primarily caused by the increase in police productivity rather than the increase in crime. Police productivity is a sum of increase and development in crime reporting and recording practices of police. The factors responsible for increased police productivity include but are not limited to changes in employment; demographic composition of employees; civilianization; per capita police officers and per capita expense of police; technological development, such as computerization, data management tools, mobile computer, and computer-aided dispatch; changes in operational strategies, such as community policing and domestic violence specialized units; and institutional changes, such as mandatory arrest policies. These factors are reported to increase the efficiency of police reporting and recording of crimes by law enforcements.

Both the data collection programs have gone through the process of maturation and development and incorporated several methodological changes of defining, collecting, classifying, and reporting crime rates. Increase in the state UCR programs and reporting agencies have certainly improved the estimate of UCR rates. Rates affecting changes of the NCVS have brought significant changes in the estimation of victimization after 1993. These methodological changes in the UCR and NCVS have shown positive relationships with continuously decreasing discrepancies between the two crime data series.

The Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics (LEMAS) survey is conducted by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) every 3 or 4 years to collect data on law enforcement from a nationally representative sample of over 3000 state and local law enforcement agencies including all the law enforcement agencies that employ 100 or more sworn officers. The last survey was conducted in 2007.

CTIA, the Wireless Association’s semi-annual wireless industry survey, develops industry-wide information drawn from operational member and nonmember wireless service providers. It has been conducted since January 1985, originally as a cellular-only survey instrument and now including PCS, ESMR, and AWS licensees.

Rape is excluded because of measurement problems and inconsistency. The 1992 NCVS methodological changes had a significant impact on the reporting of rape data. Because the purpose of this study is to explore the trends and convergence between the two crime data series over time, inclusion of rape may be problematic.

For descriptions of the dependent variables used in the analyses, refer to Fig. 1 in the literature review section.

References

Anderson, E. (1999). Code of the street: decency, violence and the moral life of the inner city. New York: W.W. Norton.

Ansari, S., & He, N. (2012). Convergence revisited: a multi-definition, multi-method.

Austin, P. C., & Steyerberg, E. W. (2015). The number of subjects per variable required in linear regression analyses. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 68(6), 627–636.

Barnett-Ryan, C. (2007). Introduction to the uniform crime reporting program. In J. P. Lynch & L. A. Addington (Eds.), Understanding crime statistics: Revisiting the divergence of NCVS and UCR (pp. 225–250). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Baumer, E. P., & Lauritsen, J. L. (2010). Reporting crime to the police, 1973–2005: a multivariate analysis of long-term trends in the National Crime Survey (NCS) and National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS). Criminology, 48(1), 131–185.

Biderman, A. D. (1967). Surveys of population samples for estimating crime incidence. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 374(1), 16–33.

Biderman, A. D., & Reiss, A. J. (1967). On exploring the “dark figure” of crime. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 374(1), 1–15.

Biderman, A. D., Lynch, J. P., & Peterson, J. L. (1991). Understanding crime incidence statistics: why UCR diverges from the NCS. New York: Springer Verlag.

Black, D. J. (1970). Production of crime rates. American Sociological Review, 35, 733–748.

Blumstein, A., Cohen, J., & Rosenfeld, R. (1991). Trend and deviation in crime rates: a comparison of UCR and NCS data for burglary and robbery. Criminology, 29(2), 237–263.

Booth, A., Johnson, D. R., & Choldin, H. M. (1977). Correlates of city crime rates: victimization surveys versus official statistics. Social Problems, 25(2), 187–197.

Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2010). Criminal victimization, 2009 (NCJ No. 231327). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Catalano, S. M. (2006). The measurement of crime: victim reporting and police recording. New York: LFB Scholarly Publishing.

Catalano, S. M. (2007). Methodological change in the NCVS and the effect on convergence. In J. P. Lynch & L. A. Addington (Eds.), Understanding crime statistics: revisiting the divergence of the NCVS and the UCR (pp. 125–155). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cohen, L. E., & Land, K. C. (1984). Discrepancies between crime reports and crime surveys—urban and structural determinants. Criminology, 22(4), 499–530.

Cohen, L. J., & Lichbach, M. I. (1982). Alternative measures of crime: a statistical evaluation. The Sociological Quarterly, 23(2), 253–266.

Decker, S. H. (1977). Official crime rates and victim survey: an empirical comparison. Journal of Criminal Justice, 5, 47–54.

Dugan, L., Nagin, D. S., & Rosenfeld, R. (2003). Exposure reduction or retaliation? The effects of domestic violence resources on intimate-partner homicide. Law & Society Review, 37(1), 169–198.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2004). Uniform crime reporting handbook. Washington, DC: Author.

Groves, R. M., & Cork, D. L. (Eds.). (2008). Surveying victims: options for conducting the National Crime Victimization Survey. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Gujarati, D. N. (2004). Basic econometric (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Kindermann, C., Lynch, J., & Cantor, D. (1997). Effects of the redesign on victimization estimates. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice Statistics.

Langan, P. A., & Farrington, D. P. (1998). Crime and justice in the United States and in England and Wales, 1981-96 (NCJ No. 169284). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Levitt, S. D. (1998). The relationship between crime reporting and police: implications for the use of uniform crime teports. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 14(1), 61–81.

Lynch, J. P. (2011). A strategic vision for the bureau of justice statistics. The Criminologist, 36(3), 1–6.

Lynch, J. P., & Addington, L. A. (Eds.). (2007). Understanding crime statistics: revisiting the divergence of NCVS and UCR (pp. 225–250). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Marvell, T. B., & Moody, C. (1996). Specification problems, police levels, and crime rates. Criminology, 34(4), 609–646.

McDowall, D., & Loftin, C. (2007). What is convergence, and what do we know about it? In J. P. Lynch & L. A. Addington (Eds.), Understanding crime statistics: revisiting the divergence of the NCVS and the UCR (pp. 93–124). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Menard, S. (1987). Short-term trends in crime and delinquency: a comparison of UCR (Uniform Crime Reports), NCS (National Crime Survey), and self-report data. Justice Quarterly, 4(3), 20.

Menard, S., & Covey, H. C. (1988). UCR and NCS: comparisons over space and time. Journal of Criminal Justice, 16(5), 371–384.

Mullins, R. (2008). Can you find me now? Cell phones hard for 911to trace. Retrieved from http://www2.tbo.com/content/2008/dec/28/280011/na-can-you-find-me-now/news-breaking/.

O’Brien, R. M. (1985). Crime and victimization data. Beverly Hills: Sage.

O’Brien, R. M. (1990). Comparing detrended UCR and NCS crime rates over time: 1973-1986. Journal of Criminal Justice, 18(3), 10.

O’Brien, R. M. (1996). Police productivity and crime rates: 1973-1992. Criminology, 34(2), 183–207.

O’Brien, R. M. (1999). Measuring the convergence/divergence of “Serious Crime” arrest rates for males and females: 1960-1995. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 15(1), 97–114.

Penick, B., & Owens, M. (1976). Surveying crime. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Rand, M. (2006). The national crime victimization survey: 34 years of measuring crime in the United States. Statistical Journal of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, 23(4), 289–301.

Rand, M. (2007). The National Crime Victimization Survey at 34: looking back and looking ahead. In M. Hough & M. Maxfield (Eds.), Surveying crime in the 21st century (pp. 145–164). Monsey: Criminal Justice Press.

Rand, M. R., & Rennison, C. M. (2002). True crime stories? Accounting for differences in our national crime indicators. Chance, 15(1), 47–51.

Rand, M. R., Lynch, J. P., & Cantor, D. (1997). Criminal victimization, 1973-95. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report: National Crime Victimization Survey. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Rennison, C. M., & Rand, M. R. (2007). Introduction to the National Crime Victimization Survey. In J. P. Lynch & L. A. Addington (Eds.), Understanding crime statistics: revisiting the divergence of the NCVS and the UCR (pp. 55–92). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rosenfeld, R., & Fornango, R. (2007). The impact of economic conditions on robbery and property crime: the role of consumer sentiment. Criminology, 45(4), 735–769.

Skogan, W. G. (1974). The validity of official crime statistics: an empirical investigation. Social Science Quarterly, 55(2), 25–38.

Skogan, W. G. (1984). Reporting crimes to the police: the status of world research. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 21(2), 113.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2011). Survey Abstracts. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/aboutus/pdf/surveyabstracts.pdf.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Sami Ansari declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ni He declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Not applicable

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ansari, S., He, N. Explaining the UCR-NCVS Convergence: a Time Series Analysis. Asian Criminology 12, 39–62 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-016-9236-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-016-9236-3