Abstract

Newly created academic programs at Brazilian universities have provided the impetus for new archaeological projects in southeastern South America during the last two decades. The new data are changing our views on emergent social complexity, natural and human-induced transformation of the landscape, and transcontinental expansions and cultural interactions across the Río de la Plata basin during the Middle and Late Holocene. We concentrate on six major archaeological traditions/regions: the Sambaquis, the Pantanal, the Constructores de Cerritos, the Tupiguarani, the Southern Proto-Jê, and the middle and lower Paraná River. Diverse and autonomous complex developments exhibit distinct built landscapes in a region previously thought of as marginal compared with cultural developments in the Andes or Mesoamerica. The trajectories toward increased sociopolitical complexity flourished in very different and changing environmental conditions. While some groups were pushed to wetland areas during a drier mid-Holocene, others took advantage of the more humid Late Holocene climate to intensively manage Araucaria forests. The start of the second millennium AD was a critical period marked by an increased number of archaeological sites, the construction of ceremonial architecture, and the intensification of landscape transformation; it also was marked by the rapid expansion of influences from outside the La Plata basin. The Amazonian Tupiguarani and Arawak newcomers brought with them significant changes in technologies and social and political structures, as well as novel landscape management practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Large river systems in the Americas were major avenues that promoted the emergence of complex societies and multiethnic cultural interactions over vast regions during the Middle and Late Holocene (e.g., Gassón 2002; Heckenberger and Neves 2009; Iriarte et al. 2004; Roosevelt 1999; Saunders et al. 1997; Schaan 2012). Southeastern South America encompasses the eastern sector of the Río de la Plata basin—the second largest river system in the Americas—and its adjacent Atlantic Coast. With several major zones of ecological and cultural diversity, this region constitutes a geographical enclave where cultural traditions converged and interacted, giving rise to a diversity of social developments during pre-Columbian times (Dillehay 1993; Iriarte et al. 2008a; Noelli 1999/2000; Politis and Bonomo 2012; Rodríguez 1992; Rogge 2005).

Long viewed as a marginal area compared to the Andes and the Circum-Caribbean (Meggers and Evans 1978; Steward and Faron 1959), we are learning that this region had an early sequence of cultural trajectories contemporaneous with the first urban societies in the Andes and the rise of the Amazonian Formative (e.g., Burger 1995; Dillehay 2014; Heckenberger and Neves 2009). During the last two decades, the archaeology of this region has received new energy through the development of several archaeological projects at national universities in Brazil (e.g., López Mazz 1999) and the arrival of land development-funded archaeology (e.g., Copé 2007; DeMasi 2006). A large portion of the original work reported in this article appears in unpublished theses, completed mainly in Brazilian universities. This renewed archaeological research, combined with new conceptual and methodological advances, allows us to discuss in detail issues relating to the emergence of social complexity, the scale and nature of past human impact on these landscapes, and the role of regional interaction networks in a way that was not possible before.

We begin with an overview of recent developments in the Middle and Late Holocene archaeology of the region, followed by a discussion of how these new data are changing our views on the emergence of social complexity, the transformation of landscapes, migrations, and the establishment of interaction spheres during the Late Holocene. The introductory sections present the diverse environments and a summary of the Middle and Late Holocene archaeological cultures of the region (Fig. 1). In the following thematic sections, we present key findings and emerging research agendas for each archaeological culture. Finally, we summarize the major new findings and briefly discuss the main thematic concerns in the context of South America. We focus on major trends without intending to provide a complete overview of all recent excavations or interpretations. Not included in our review are the archaeology of Paraguay and large parts of the Gran Chaco and the archaeology of mid-Holocene hunter-gatherers. Similarly, we highlight major historical trends in each particular section but do not produce a detailed account of the history of archaeological investigations in each region (see López Mazz 1999; Noelli 2005; Politis 2003).

Map (right) showing approximate locations of major archaeological traditions and archaeological sites in southeastern South America during the Middle and Late Holocene that are discussed in the text. Cerritos: 1, India Muerta region (Los Ajos, Estancia Mal Abrigo, Puntas de San Luis); 2, Lemos; 3, Pago Lindo; 4, Laguna de Castillos; 5, Laguna Negra (Los Indios, CH2D01, CH1D01). Sambaquis: 6, Santa Marta Lagoon and Cape (Caieiras, Congonhas, Jabuticabeira, Carniça, Mato Alto, Morrote); 7, Babitonga Bay; 8, Guaratuba and Paranaguá Bays. Pantanal: 9, MS-MA-50 site. Southern Proto-Jê: 10, Pinhal da Serra and Anita Garibaldi regions (Avelino, Chico Carneiro, Leopoldo, Ari, Posto Fiscal, Reco, SC-AG-98, SC-AG-108); 11, Campo Belo and San José do Cerrito regions (Abreu and Garcia, SC-CL-52, Rincão dos Albinos); 12, PM01; 13, SC-CL-37; 14, SC-AG-12; 15, PR-UB-04; 16, Urubici region (Avencal, Bonin). Goya-Malabrigo: 17, Tres Cerros; 18, Tapera Vázquez. Tupiguarani: 19, Pardo River valley; 20, Pelotas region; 21, RS-T-114. Paraná Delta region: 22, Arroyo Fredes, La Bellaca, Las Vizcacheras. Pollen sites: 23, São Francisco de Assis; 24, Morro Santana; 25, Cambará do Sul. Schematic chronological chart (left) of major archaeological traditions in southeastern South America

The Environmental Diversity of the La Plata Basin and Its Adjacent Littoral Zone

The La Plata basin drains about one-quarter of the South American continent. It encompasses parts of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay, covering 3,100,000 km2. Like the Amazon River system, it comprises a network of huge rivers that constituted a major avenue for communication among different pre-Columbian groups. There are no important geographical barriers that separate these two large river systems. South of the Amazon, the annual inundation of the Llanos de Mojos and the Gran Chaco merge the basins of the Río Madeira and the Río Paraguay, respectively, into a vast “freshwater sea,” opening up a network of waterways that extend south to the Río de la Plata estuary (e.g., Lathrap 1970; Lothrop 1931; Torres 1911). The movement of people was certainly facilitated by the lack of geographical barriers and the connectedness of the Amazon–La Plata basins. Most of the tropical, subtropical, and parts of temperate areas of South America were connected by waterways that were easily traveled by groups who possessed watercraft, such as the Tupiguarani and Arawak. The ease of water travel has implication for the migration and expansion of people.

The Río de la Plata basin and adjacent Atlantic Coast encompass an enormous ecological diversity characterized by a mosaic of environments that shaped, and were shaped by, different types of pre-Columbian land use. The Atlantic coastal plain to the east, with its rich estuaries, lagoons, and mangroves, is covered by restinga vegetation (sandy soil grasslands, shrubs, and forests). The southern Brazilian highlands constitute a plateau above the Atlantic Coast, from nearly 1900 m above sea level in the easternmost peaks of Serra do Mar and sloping west to the Río de la Plata basin. Subtropical mixed Araucaria forest and high-altitude grasslands cover the plateau. Its eastern escarpment is dominated by the Atlantic Forest—one of the last remaining biodiversity hotspots on earth (Myers et al. 2000); subtropical semideciduous Interior Atlantic Forest covers the western and southern escarpment. West and south of the plateau are large expanses of savannah and grasslands intersected by gallery forest, xerophytic forest, palm groves, and vast areas of wetlands including the Pantanal, the world’s largest tropical wetland (140,000 km2) (Clapperton 1993). To the south, large floodplains continue virtually uninterrupted, spreading through the humid Chaco region of Paraguay and Argentina. Hundreds of miles from the Río de la Plata, the Paraná deposits silt to form the innumerable and intermittent islands of the Paraná Delta, characterized by subtropical wetlands, riverine islands and grasslands, and xerophilous and subtropical semideciduous forest.

Paleoecological studies show that the region experienced major changes in climate, vegetation, fire regimes, and sea levels during the Middle and Late Holocene, which created constraints and opportunities for pre-Columbian populations (e.g., DeBlasis et al. 2007; Iriarte 2006b). While the mid-Holocene drought seems to have promoted increased sedentism in the form of mounded villages around the wetlands of southwest Uruguay, the more humid climate of the Late Holocene is likely to have encouraged the spread of forest and facilitated the expansion of Araucaria forests in the southern Brazilian highlands. Some groups were fairly restricted to certain environmental zones, such as the Constructores de Cerritos (hereafter called Cerritos) in wetlands, the Sambaquis in the coastal bays, and the Tupiguarani who mostly expanded to forested floodplains. Other groups, like the Southern Proto-Jê, thrived in a diversity of environments including the Atlantic coastal plain, the Atlantic Forest escarpment, and the southern Brazilian plateau.

Overview of Middle and Late Holocene Archaeology in the La Plata Basin

The Middle Holocene

Renewed archaeological work in the region reveals the appearance of social complexity during the mid-Holocene, as exemplified by the Cerritos, the Sambaquis, and potentially the preceramic Pantanal. These developments, contemporary with early urban societies in Peru and the Amazonian Formative, indicate that the region was a major center of cultural development.

Sambaquis

Shell mounds (or sambaquis) on the Brazilian coast have been described since the 16th century. Many have disappeared as a result of urban development and intensive mining for construction fill and lime production. They occur all along the extensive Atlantic Coast, usually clustering in rich bays or lagoons, where a range of land and aquatic resources is available. Sambaquis are more common along the southern Brazilian coast, from Río de Janeiro to Santa Catarina, including Paraná and São Paulo (Gaspar, 1998, 2000; Lima and López Mazz, 1999; Prous, 1992). Shell mounds farther north have only occasionally been described (e.g., Bandeira 2008; Calderón 1964; Simões and Correa 1971), while the mounds become smaller and infrequent south of this region (Pestana 2007; Rogge and Schmitz 2010).

The shell mounds typically occur in highly productive bay and lagoon ecotones where the mingling of salt and freshwater supports mangrove vegetation and abundant shellfish, fish, and aquatic fowl. The Sambaquis cultural tradition spans a time interval roughly between 8000 and 1600 years ago, but the bulk of radiocarbon determinations on coastal shell mounds are concentrated between 5000 and 2000 cal yr BP—“the golden age” of the Sambaquis culture (Gaspar et al. 2008; Lima 2000; Prous 1992). Along the Atlantic Coast of Río Grande do Sul in Brazil and Uruguay, the mounds were replaced by the Cerritos cultural tradition.

Pantanal

During the mid-1990s, an attempt to map the largely unexplored region resulted in the documentation of 200 archaeological sites across an area of 20,000 km2 around the city of Corumbá in Mato Grosso do Sul state, Brazil (Schmitz et al. 1998), which began to fill the vacuum of archaeological information for this crucial region at the crossroads of Amazonia and the Río de la Plata.

As in the wetlands of southeastern Uruguay (Iriarte 2013), the Llanos de Moxos in Bolivia (Lombardo et al. 2013), and the Paraná Delta (Bonomo et al. 2011b), mounds in the Pantanal are easily recognized as forest islands via remote sensing. Occupation of the Pantanal goes back to circa 9200 cal yr BP, as evidenced by a preceramic site located on the terraces of the Paraguay River. After a hiatus of around 4200 years, the preceramic component of mounds dated to 5000 cal yr BP began to appear in low-lying wetland areas, followed by the ceramic component around 2200 cal yr BP (Schmitz et al. 1998). Peixoto et al. (2001) have suggested that the more intense occupation of the Pantanal was related to the stabilization of the region’s lakes and fluvial channels, which started during the mid-Holocene around 5000 cal yr BP; recent palaeoecological work has confirmed this (Whitney et al. 2011).

The first millennium BC marks the beginning of the ceramic Pantanal tradition (Schmitz et al. 1998). In the municipalities of Corumbá and Ladário, intensive archaeological survey has revealed a major increase in the number of Pantanal tradition sites. The definition of a new ceramic tradition highlights the need to start from the very basics of cultural chronology in many of these regions. The Pantanal tradition encompasses four different phases defined by technological characteristics: Pantanal, Jacadigo, Castelo, and Taimã (Migliacio 2000; Rogge 2000; Schmitz et al. 1998). These ceramic “styles” are not restricted to the Brazilian Pantanal (De Oliveira 2004, p. 45) but also are present in the Bolivian Pantanal, the Argentinian Chaco, and Paraguay (e.g., Rodríguez 1992; Willey 1971). Regional differences in pottery styles across this vast region are likely to come into closer focus as research progresses. For example, Schmitz et al. (2009) argue that there are slight differences between the left and right margins of the Paraguay River in the temper and external surface finishing of the pottery, as well as in bone point morphology.

Constructores de Cerritos

Mound-building pre-Columbian cultures date back to circa 4750 cal yr BP and generally are referred to in Uruguay as Constructores de Cerritos; they represent one of the less mature Early Formative cultures of South America. The Cerritos are divided into two main periods: the preceramic mound period from around 4750 to 3000 cal yr BP, followed by the ceramic mound period (Iriarte 2006a, p. 648, fig. 2). This archaeological culture extended along the coastal and inland wetlands and grasslands on the Atlantic Coast between 28° and 36°S (Bracco et al. 2000a; Iriarte 2003; Schmitz et al. 1991). The region is characterized by a patchwork of closely packed environments including wetlands, wet prairies, grasslands, riparian forests, stands of Butia palms, and the Atlantic Ocean sand dunes and lagoons (Iriarte and Alonso 2009; López Mazz et al. 2014).

The Late Holocene

During the Late Holocene many regions of lowland South America experienced population growth and regional integration, as well as a marked increase in monumental constructions, the development of regional ceramic styles, and long-distance population expansions. Lowland societies also began to transform the landscape at a scale not previously seen. From French Guiana to southern Chile, extensive agricultural landscapes began to be built, such as raised-field systems in seasonally flooded savannahs. Human-made soils—anthropogenic dark earths—possibly associated with more sedentary settlements, and later with more intensive agriculture, began to appear along the bluffs of major rivers in Amazonia (Bush et al. 2008; Denevan 2001; Heckenberger and Neves 2009; Iriarte 2009).

During the late Holocene the La Plata basin constituted a geographical enclave where major cultural traditions from the tropical forests, like the Tupiguarani (Brochado 1984; Noelli 1998), the Goya-Malabrigo archaeological entity—possibly related to Arawak people (Métraux 1934; Nordenskiöld 1930; Politis and Bonomo 2012, 2015)—and the Southern Jê (Iriarte et al. 2008a; Noelli 2005) converged and interacted during pre-Columbian times.

The arrival of these external influences does not necessarily mark an abrupt break with the mid-Holocene cultures of the region. For the Sambaquis, the arrival of Southern Jê influences seems to have been a complex process involving population replacement in some areas and the adoption of ceramics by local groups in others (DeBlasis et al. 2014; Okumura and Eggers 2005). Similarly, the Tupiguarani advance over the La Plata basin was marked not only by conquest and displacement of previous groups, but also by interaction with them, including exchange of objects, styles, and possibly people, especially in ecotone regions (e.g., Chmyz and Sauner 1971; DeMasi e Artusi 1985; Ribeiro 1991; Rogge 2005; De Souza et al. 2016).

Southern Proto-Jê

During the last two decades there have been major developments in the archaeology of the southern Brazilian highlands in relation to the Taquara/Itararé tradition. First defined by Menghin (1957) as El Doradense in Misiones Province, Argentina, this archaeological tradition was known as Itararé and Casa de Pedra in Paraná (Chmyz 1967) and Taquara in Santa Catarina and Río Grande do Sul states (Miller 1967). More recently, Beber (2005) used the term Taquara/Itararé to refer to this broadly defined archaeological tradition.

Recent studies by archaeologists (DeMasi 2009; Noelli 2005), anthropologists (Silva 2001), and historians (Dias 2005) emphasize the historical continuity between the Taquara/Itararé tradition and the Southern Jê historic groups. We use the prefix “proto” to encompass all the ancestors of modern Southern Jê people in this tradition, including the former speakers of the extinct Southern Jê languages: Ingain and Kimdá (Jolkesky 2010).

The Taquara/Itararé tradition that is the material correlate of Southern Proto-Jê groups dates back to c. 2220 cal yr BP and extends to the beginning of the 19th century. It is mainly characterized by its diagnostic small ceramics with thin walls, the construction of subterranean houses (hereafter called pit houses) in the highlands, collective burials in caves, rock art, and elaborated mound and enclosure complexes (e.g., Araújo 2007; Beber 2005; DeMasi 2009; Iriarte et al. 2013; Noelli 2005; Ribeiro 1999/2000; Riris and Corteletti 2015; Schmitz 1999/2000). Beyond the general label of Southern Proto-Jê and its shared material culture, there is increasing recognition that this broadly defined tradition spread over a vast area (more than 600 km north to south) encompasses a remarkable range of local variability in social and ritual organization. This is exemplified by the Canoas and Pelotas River basins (Copé 2007; Corteletti et al. 2015; DeMasi 2009; De Souza and Copé 2010; Iriarte et al. 2013; Schmitz et al. 2010; 2013b), Misiones Province, Argentina (Iriarte et al. 2008a, 2010; Menghin 1957; Riris 2015), the Atlantic Coast (Silva et al. 1990), the Atlantic forest escarpment (Farias et al. 2015), the north of Paraná state (Araújo 2001; Parellada 2005), and the southern portion of the southern Brazilian highlands (Copé 2006, 2007; Copé et al. 2002; Corteletti 2008; Schmitz et al. 2002).

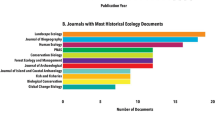

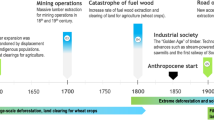

Archaeological projects during the last two decades have begun to reveal general chronological trends in the development of the Southern Proto-Jê. Available radiocarbon dates indicate that Taquara/Itararé sites began to spread in the second millennium BP, becoming more common around 1500 cal yr BP and peaking after around 1000 cal yr BP (Fig. 2). Around 1000 cal yr BP, we also see the appearance of mound and enclosure complexes and oversized pit structures (Copé 2006; Corteletti 2012; Iriarte et al. 2013; Schmitz et al. 2013a); significantly, this appearance coincided with the expansion of Araucaria angustifolia (Paraná pine) as evidenced by pollen records along the southern Brazilian highlands (Iriarte and Behling 2007; see Gessert et al. 2011, p. 30, fig. 1).

Composite graph showing dates of all archaeological sites, mound and enclosure complexes, and oversized pithouses combined with Araucaria forest and Campos (high-altitude grasslands) pollen curves from Cambará do Sul record (Behling et al. 2004). The composite graph illustrates the correlation of major cultural transformations (increase in archaeological sites, appearance of oversize pit houses, and the arrival of monumental architecture) with the expansion of Araucaria forest.

The Tupiguarani

The investigation of population expansions in the past—and the correlation with existing distributions of archaeological sites, contemporary languages, and human population genetics—is one of the most controversial topics in linguistics, archaeology, and human genetics in lowland South America (e.g., Heckenberger 2002; Hornborg 2005; Neves 2011; Politis and Bonomo 2012; Santos et al. 2015). The expansion of the archaeologically defined Tupiguarani tradition along some 5,000 km of the Atlantic Coast and through the major rivers in the hinterland represents one of the major migrations in the lowlands of South America during the Late Holocene (Bonomo et al. 2015; Brochado 1984; Noelli 1998).

The greatest diversity of Tupian languages is found in the southwestern Amazon. Consequently, most linguists point to this region (around the modern Brazilian state of Rondônia) as the center of origin of this linguistic stock, which had started to expand around 4,000–5,000 years ago (Migliazza 1982; Rodrigues 1984; Storto and Moore 2001; Urban 1992; Walker et al. 2012). Recent craniometrics studies (Neves et al. 2011) also point to an Amazonian origin of Tupí-Guaraní speakers. Interestingly, the purported homeland of the Tupian stock in the southwestern Amazon has one of the longest cultural histories in the entire Amazon. Early Holocene shell middens have recently been discovered in the Llanos de Moxos (Lombardo et al. 2013) and the Brazilian Guaporé River (Miller 1992, 2013), while other evidence includes the presence of 5,000-year-old anthropogenic dark earths, one of the earliest centers of pottery production—dated to around 4,000 cal yr BP (Miller 1992, 2009, 2013)—and the likely cradle of manioc (Manihot esculenta) domestication (Olsen and Schaal 1999).

The earliest material correlates for the Tupian speakers in southwestern Amazonia remain a matter of discussion (Almeida 2013; Almeida and Neves 2015; Cruz 2008; Miller 2009). Although early syntheses postulated that the Tupiguarani pottery was derived from the Amazon polychrome tradition (Brochado 1984), refinements in chronology and stylistic analyses suggest it was an earlier, though related development (Almeida 2013; Heckenberger et al. 1998). Pottery clearly identifiable as Tupiguarani appears in the archaeological record around 2700 cal yr BP (Corrêa 2014, p. 255); this broadly coincides with the linguistic estimate, based on glottochronology, for the beginning of the Tupí-Guaraní diaspora (e.g., Rodrigues 1964) around 2,500 years ago.

Despite this unresolved debate, it is clear that at least by around 2000 cal yr BP groups carrying Tupiguarani ceramics arrived in the southeastern sector of the Río de La Plata basin and started colonizing and establishing large villages in forested areas along the major river courses (Bonomo et al. 2015; Brochado 1984; Prous 1992). Based on the linguistic distribution of the ancient Guarani family, mainly restricted to the southeastern sector of the Río de La Plata basin and the adjacent Atlantic Coast, the Tupiguarani have been renamed the Guarani archaeological tradition (Bonomo et al. 2015). The archaeological correlates of the Guarani archaeological tradition are more restricted and include ceramic dishes, shallow bowls, and large jars with restricted orifices and conical bases; vessels with corrugated, nail-incised, brushed, or painted surfaces; lip plugs; polished stone axes; secondary burials in urns; and bounded, dark terra preta sediment, associated with households and other architectural structures (Bonomo et al. 2015, p. 55). In addition to these material traits was a preference for subtropical deciduous forest environments close to navigable rivers and the practice of polyculture agroforestry, including the management of old fallows and secondary forests (Scheel-Ybert et al. 2014).

Paraná River Delta

The region of the Paraná Delta has received renewed archaeological interest, in particular in relation to the Goya-Malabrigo archaeological entity (Cerutti 2003; Politis and Bonomo 2012) and the archaeology of complex hunter-gatherers adapted to the lower Paraná River wetlands. Although the region was the focus of archaeological investigations at the end of the 19th century (Ambrosetti 1893) and the first part of the 20th century (e.g., Bonomo 2013; Lothrop 1931; Torres 1911), archaeological research in the region was stagnant until the last decade (see Bonomo et al. 2011a). New research on the Goya-Malabrigo is reframing old research agendas, mainly based on chronology and the definition of ceramic styles, to discuss incipient social hierarchy and the development of early village life, as well as the role of cultigens in the diet of these Late Holocene groups. The earliest date from mound contexts associated with the Goya-Malabrigo in the middle Paraná River is c. 2025 cal yr BP (Arroyo Aguilar 2) (Politis and Bonomo 2012, 2015), though most of the dates show a more intense occupation of the Paraná Delta and the lower Uruguay River between 1200 cal yr BP and the time of European contact (Bonomo et al. 2011a; Politis and Bonomo 2015). Goya-Malabrigo, previously known as Ribereños Plásticos, has recently been more strictly defined. This new definition is based on the diagnostic morphological and stylistic features found in its ceramics, as well as the construction of artificial mounds, the existence of a mixed economy and riverine settlement patterns, and a close relationship (technical, economic, constructive, and cosmological) with clay (Politis and Bonomo 2015). Diagnostic ceramics include globular vessels; modeled zoomorphic adornos affixed to bowl rims representing bird heads, mammals, reptiles, and mollusks; and the unique alfarerias gruesas represented by bell- or tubular-shaped objects of thick-walled pottery. The objects usually exhibit drag and jab punctuations, incisions, rows of punctate dots, and fingernail impressions. Red and white slip also is common (Cerutti 2003, pp. 118–123; Politis and Bonomo 2012). According to Politis and Bonomo (2015), the zoomorphic adornos demonstrate the incorporation of animals into the sphere of cultural representations, where birds played a prominent role.

Emergence of Social Complexity

The emergence of cultural complexity has been a key topic in the study of the dynamics of intermediate-level societies (sensu Upham 1990) (e.g., Arnold 1996; Brumfiel and Fox 1994; Enrenreich et al. 1995; Price and Brown 1985; Price and Feinman 1995). Reevaluations of progressivist typological frameworks (Fried 1967; Service 1962) have recognized that a degree of inequality exists even in the most egalitarian societies (Cashdan 1980; Collier and Rosaldos 1982; Flanagan 1989; McGuire and Paynter 1991), that the origins of agriculture are not intrinsically related to the emergence of cultural complexity (Arnold 1996; Koyama and Thomas 1981; Price and Brown 1985; Price and Gebauer 1995; Upham 1990), and that there is more social variability among Early Formative societies than previous neo-evolutionary concepts of sociocultural complexity had accounted for (Baker 1996; Blanton et al. 1996; Drennan 1991,1995; Nelson 1995). These reconceptualizations demonstrate that different aspects of cultural complexity, such as inequality, differentiation, scale and integration, and their correspondent list of archaeological correlates (Creamer and Haas 1985; Peebles and Kus 1977), do not necessarily covary from one stage of cultural evolution to the other; neither do they all need be present in every Early Formative society. On the contrary, social variation in Early Formative societies can be understood to have been multidimensional and continuous (Feinman and Nietzel 1984; Plog 1974; Upham 1987; Yoffee 1993). In response to these reevaluations, archaeologists over the last two decades have begun to look beyond neo-evolutionary frameworks that stress functionally oriented ecological and economic explanations, turning instead to considerations of ideology, power, and factional competition while adopting a more historically based approach (e.g., Canuto and Yaeger 2000; Chapman 2003; Clark and Blake 1994; Dietler 2001; Parkinson 2002; Pauketat 2001). These perspectives differ from oppositional views of simple/egalitarian versus complex/hierarchical, in that other concepts are employed. Actor-based perspectives (e.g., Clark and Blake 1994), heterarchy (Crumley 1987), and situationalism are explored, along with network and corporate strategies (Blanton et al. 1996), communalism (Saitta 1997), and a more flexible concept of tribal societies as defined by Parkinson (2002). As a result, most archaeologists today recognize various pathways to emergent complexity and employ various models to explain it. They recognize that social power is constructed in significantly different ways by aspiring political actors involving competitive strategizing, which may include feasting (e.g., Clark and Blake 1994; Hayden 1995), the practice of extensive or intensive agriculture (e.g., Drennan 1995; Gilman 1991), participation in long-distance exchange and craft production of luxury goods (e.g., Helms 1994), warfare (Redmond 1994), the appropriation of the means of expressing ideological knowledge (e.g., Aldenderfer 1993; Drennan 1976; Earle 1991), and/or the combination of many of the above (e.g., Spencer 1994). Under this more productive and informative approach, archaeologists have focused their efforts on understanding how these societies became complex, rather than simply trying to define how complex they were (Nelson 1995).

Many of these new approaches concentrate on more particular historical developments (e.g., Pauketat 2001) and incorporate the concepts of practice (Bourdieu 1977) and structure (Giddens 1979) into their interpretations of specific historical trajectories. At the same time, aspects relating to the perception, memory, ideology, and underlying structural principles and meanings of Early Formative landscapes are taken into account (e.g., Ashmore and Knapp 1999; Barrett 1996; Bradley 1998; Dillehay 2007; De Boer 1997; Edmond 1999; Feinman 1999; Iriarte et al. 2013; Thomas 1999; Tilley 1995); several authors have emphasized the importance of the landscape as a means of encapsulating and transmitting historical memory (e.g., Bender 1993, 2002; Criado Boado et al. 2006; Santos-Granero 1998, 2004).

Despite decades of culture history approaches, archaeologists in the Río de la Plata basin have only recently begun to discuss different aspects of emergent social complexity beyond the simple categorization of archaeological traditions into evolutionary categories (e.g., Gaspar 1998; Iriarte et al. 2004; Lima and López 1999; Politis et al. 2011). In some regions, such as the Pantanal, much research still focuses on defining new cultural traditions. But in others, such as the southern Brazilian highlands, archaeology has reached a maturity where we can now move to more nuanced interpretations and conceptual issues beyond cultural chronology and discuss emergent cultural complexity along the lines of regional settlement patterns, site-level community patterns, mound uses, construction history and architecture, mortuary practices, and subsistence economy. As a result of decades of sustained systematic archaeological research coupled with new methodological advances, we can now begin to reconstruct regional settlement patterns of the Cerritos in the Campos region (e.g., Gianotti and Bonomo 2013; Iriarte 2006a, 2013). At the site level, archaeologists’ interests in revealing community patterns or recurrent architectural patterns in complex sites, beyond the study of single mounds or pit houses, also are paying dividends by showing recurrent patterns of community organization (Gianotti and Bonomo 2013; Iriarte 2006a, 2013). Advances also have been made on the documentation of mound-building practices and the uses of mounded architecture (e.g., Bonomo et al. 2011a; Castiñeira et al. 2014; DeBlasis et al. 2007; DeMasi 2009;). Renewed excavations, more comprehensive radiocarbon chronologies, detailed faunal analysis, artifact composition and density trends, and the novel application of micromorphology and phytolith analysis are revealing more complex construction histories than previously reported (e.g., Castiñeira et al. 2014; Iriarte 2003; Suárez Villagran and Gianotti 2013). Last but not least, the subsistence economy of these groups is also beginning to be revealed. Archaeobotany is still in its nascent stages in the Río de La Plata basin (Iriarte 2007). The systematic implementation of new archaeobotanical methods, in particular microfossil botanical analyses (phytolith, pollen, starch grains, and charcoal), is leading to a better understanding of the plant component of diets and the role of domesticated plants, which has implications for our understanding of the economy and mobility of these groups (Bonomo et al. 2011b; Corteletti et al. 2015; Iriarte et al. 2004; López Mazz et al. 2014), as well as the ritual aspects (Iriarte et al. 2008a). The role of maize in the diet of groups such as the Goya-Malabrigo and Tupiguarani of the Paraná Delta is also beginning to be revealed through stable carbon isotope analysis (Loponte and Acosta 2007).

Here we present a summary of new findings that touch on the aspects of the emergence of social complexity. We discuss different aspects of emergence complexity in terms of regional settlement patterns, site-level community organization, earthwork use and construction history, mortuary practices, and subsistence economy.

Constructores de Cerritos

In southeastern Uruguay, aerial photography has played a major role in the documentation of settlement patterns, aided by earthen mounds that are highly visible on aerial photographs (Bracco and López Mazz 1989; Iriarte 2013). At a macroregional scale, encompassing the entire Cerritos region, Bracco (2006, p. 513; fig. 1) has shown how the largest aggregations are located on the middle and upper course of streams. Bracco et al. (2005) estimated the existence of around 1,500 mounds within the Uruguayan southern sector of the Laguna Merin basin (30,000 km2). Similarly, in northeastern Uruguay, Giannotti (2004) has documented the presence of 1,023 mounds, consisting of 97 clusters of different sizes with large (50–80), medium (15–30), and small (2–5) clusters of mounds (Gianotti 2000, 2005; Gianotti and Bonomo 2013, p. 131).

The India Muerta wetlands are one of the more intensively studied areas (Fig. 3). Investigations in the early 1990s documented the presence of numerous large and spatially elaborated mound complexes, some of them, like Estancia Mal Abrigo, consisting of 66 mounds; these investigations firmly established the beginning of the preceramic mound period at around 4,750 cal yr BP (Bracco 2006; Iriarte et al. 2001). Settlement pattern research revealed that mound sites are confined to wetland floodplains in ecotonal areas characterized by fertile soils within a mosaic of wetlands, wet prairies, grasslands, riparian forests, and palm groves (Bracco 2006). A more nuanced analysis by Iriarte (2003, 2006a) revealed a dual distribution pattern for mound sites in this region. Small sites (1–3 mounds) generally occur in the wetland floodplains on top of the most prominent levees following the courses of streams and exhibiting a linear/curvilinear pattern. In contrast, in the more stable locations of the landscape, such as the flattened spurs of hill ranges (e.g., the Sierra de los Ajos) adjacent to wetland floodplains—which are secure from flooding and have immediate access to resource-rich and fertile wetlands—mound sites are large, numerous, and spatially complex, covering up to 60 ha. In the nuclear sector of this region, the average distance between large mound complexes is less than 2 km (Bracco 2006).

Community patterns or the lack of them have been at the center of discussions about the complexity of the Cerritos. During the first archaeological reconnaissance of the region in the mid-1960s, archaeologists interpreted mound sites as the result of successive short-term occupations of hunters, gatherers, and fishers who moved seasonally to exploit locally rich environments (Brochado 1984; Schmitz et al. 1991). The presence of postholes and hearths, domestic debris food preparation, tool manufacture and maintenance, and occasional burials were used to infer the habitation nature of the mound. In the mid-1980s, the Archaeological Salvage Program of the Laguna Merin Basin (CRALM) began systematic archaeological fieldwork in Uruguay. Initial excavations on small two-paired mound sites, which yielded complex arrays of ceramic mound period multiple burials, led the researchers to characterize these sites as ceremonial and/or mortuary in nature (Cabrera et al. 1989). The societies were typified as complex hunter-gatherers adapted to a resource-rich wetland environment (López Mazz and Bracco 1994). The researchers began to recognize the presence of large mound complexes with a high degree of similarity in ground plan, as well as the presence of an extensive off-mound area associated with the mounds (López Mazz and Gianotti 1998). In 1996, the Arqueología de las Tierras Bajas international conference included the participation of archaeologists investigating Early Formative societies from across the Americas (Durán and Bracco, 2000). This provided the much-needed pan-American comparative perspective that enabled Uruguayan archaeologists to start viewing the Cerritos not as simple or complex hunter-gatherers but as intermediate-level societies living in well-planned villages (Dillehay, n.d.). Subsequently, the investigation of community patterns has become a prolific focus of research. It was recognized that these sites contain varied mounded architecture geometrically arranged in circular (e.g., Estancia Mal Abrigo), elliptical (e.g., Damonte), and horseshoe formats (e.g., Los Ajos), surrounding a central communal space and accompanied by vast outer sectors that generally exhibit more disperse and less formally integrated mounded architecture (Fig. 4; Bracco et al. 2000b; Iriarte 2003, 2006a, 2013; Iriarte et al. 2001; López Mazz and Gianotti 1998). Bracco (2006, pp. 520–521, figs. 8 and 9) shows how within the sites the orientation of the mounds and the distance between them are fairly regular, reinforcing the idea that these were well-planned settlements. Giannoti and Bonomo (2013, p. 136, fig. 2) have recorded similar patterns in northeastern Uruguay, where a parallel linear arrangement, suggesting dual symmetrical organization, also has been identified (e.g., Echenagusía site).

In addition, the interpretation of the uses and construction history of mounds in the region has been subject to debate in relation to the habitation versus ceremonial nature of these earthen structures (Bracco et al. 2008; Iriarte et al. 2008b), with implications for cultural complexity.

Originally interpreted by Programa Nacional de Pesquisas Arqueológicas (PRONAPA) researchers in the early 1970s as the domestic spaces of mobile hunter-gatherers (Schmitz et al. 1991), the features were considered by Uruguayan archaeologists to be the burial mounds of complex hunter-gatherers (López Mazz and Bracco 1994). Influenced by landscape archaeology approaches (Criado Boado 1993), the appearance of mounds was seen to reflect a major breakthrough in the history of hunter-gatherers in the region, with the onset of mound-building practices perceived as an innovative behavior where groups “show the intention” to monumentalize the landscape by constructing ceremonial/monumental architecture (Gianotti 2000; López Mazz 2001; Pintos 2000a). López Mazz (2001, p. 237) views the beginning of mound construction as “…a novel cultural behavior of mid-Holocene specialized hunter-gatherers that started building mounds in strategic locations of the landscape previously characterized as hunting camps”; the first mounds were the product of highly mobile preceramic hunters-gatherers who had long hunted in the region. According to López Mazz, possible functions of these older mounds was to serve as territorial markers that signaled exploitation rights to zones of concentrated resources and to facilitate travel in this flooded landscape. In a similar vein, Gianotti (2000, p. 90) interpreted the earthen structures as monuments that represent the first evidence of “an effective transformation of the natural environment, the narrowing of the breach that exists between nature and culture” (see also Criado Boado et al. 2006). Furthermore, Pintos (2000a) suggested that the construction of mounds in the Laguna de Castillos basin should be interpreted as the appearance of monumental architecture. Since mounds contain burials, they conform to a landscape “connoted by the monumentalization of the dead” (Pintos 2000a, p. 78). Following Vincent (1991), Pintos sees in the monumentalization of the death of certain individuals as the historic consolidation of a new social order, where ancestors played a major role. This change reflects the transition from a classificatory to a lineage system of kinship relations (sensu Meillaisoux 1978).

As investigations continue in the region, the complex relationship between episodes of construction, maintenance, remodeling, and reuse of pre-existing mounds is becoming clearer (Bracco et al. 2000b; Iriarte 2006a; López Mazz et al. 2014; Suárez Villagran and Gianotti 2013). There is also increasing recognition that the dominant function or behaviors that created the mounds shifted over time (e.g., Bracco et al. 2000b; Iriarte, 2006a; Suárez Villagran and Gianotti 2013). For example, excavations at the Los Ajos sites revealed a complex construction history and varied uses of mounds throughout their use life. The combined analysis of stratigraphy, artifact and ecofact composition, and horizontal spatial distribution of lithic debitage density showed that during the preceramic mound component, Mound Gamma was a residential area that grew through the gradual accumulation of occupational refuse. Despite intensive excavation in the center of the mound, no clear house features were identified. However, horizontal density trends of lithic debitage showed a consistent pattern, characterized by the presence of a central area of low density and a periphery exhibiting higher artifact density. The central zone of the mound has been interpreted as a regularly maintained habitation space and the periphery as a zone where trash was deposited (Iriarte 2003, 2006a). The lithic assemblage indicates that tool manufacture, use, and maintenance took place at Los Ajos. Local raw materials, mainly rhyolite and quartz, were brought to the site, where all stages of lithic reduction are represented, including core reduction, tool manufacture and use, and maintenance/rejuvenation. The generalized, nonspecific tool assemblage comprises a broad range of different tool types that include flake knives, end scrapers, wedges, notches, points/borers, and hafted bifaces; they indicate that Mound Gamma was a domestic area where a wide range of activities were carried out (Iriarte 2003; Iriarte and Marozzi 2009).

Similar complex histories have been recorded at the Lemos and Pago Lindo mound sites in northeastern Uruguay. The presence of hearths, postholes, and linear structures possibly associated with small constructions shows the domestic nature of the Lemos site, which was occupied between 3485 and 3280 cal yr BP. The mound was remodeled during the ceramic period (Gianotti and Bonomo 2013). Micromorphological analysis at the Pago Lindo archaeological complex has also recognized a distinct activity area interpreted as a domestic hut built over a platform, circa 1485 cal yr BP (Suárez Villagran and Gianotti 2013). As with the artifact density analysis of the Los Ajos preceramic mound component, these researchers interpreted the presence of a small quantity of macroscopic bone and charcoal fragments, and the complete absence of microbioarchaeological remains, as evidence of the regular practice of cleaning the occupation surfaces at the center of mounds. Excavations in northeastern Uruguay corroborate the fact that mounds started as habitation structures that grew intentionally or unintentionally through the gradual accumulation of domestic refuse.

Research is also showing that during the succeeding ceramic mound period (c. 3280–500 cal yr BP) there was a marked increase in the number of sites, the appearance of collective cemeteries, and a formalization and spatial differentiation of the earthen mound architecture. This appears to represent an early and distinct civic-ceremonial architectural tradition in lowland South America (Iriarte 2006a; Iriarte et al. 2004). The accretional residential mounds were the backdrop for these activities. For example, during the preceramic component in the Los Ajos mound complex, we saw the appearance of a household-based community distributed around a central public space; the ceramic mound component, however, witnessed the appearance of internal site stratification, characterized by the formalization and spatial differentiation of the inner precinct with respect to an outer, more dispersed and less formally integrated peripheral area. Low, circular, dome-shaped mounds were transformed into more imposing quadrangular platform mounds through gravel capping episodes. Similar practices were documented at the Puntas de San Luis mounds, where burnt chunks of termite mounds were used as construction material during the ceramic mound period to heighten and reshape mounds (Bracco et al. 2000b). Earthen architecture also served as funerary monuments, which represent first-order elements for the social construction of the landscape (Bonomo and Gianotti 2013; Criado Boado et al. 2006). In sum, research designs specifically tailored to reveal community patterns have been successful in showing that the large preceramic mound complexes in the India Muerta wetlands were neither the result of random, successive short-term occupations of mobile hunter-gatherers (Schmitz et al. 1991), nor the burial mounds or monuments of complex hunter-gatherers, as previously proposed (Bracco et al. 2000a; Gianotti 2000; López Mazz 2001). Instead they were well-planned plaza villages built by people who practiced a mixed economy (see below).

Burials in mounds appeared around the first millennium BC, during the later preceramic mound period. A diversity of primary and secondary burials is evident, including bundles, isolated bone fragments with signs of trauma (e.g., cut marks, intentional fractures, burnt alteration) (Gianotti 1998; Gianotti and López Mazz 2009; Pintos and Bracco 1999), and the presence of animals including dogs (Canis familiaris) (Criado Boado et al. 2006).

No clear signs of differential burial practices have been recovered for the Cerritos. One of the more intensively studied sites is CH2D01, consisting of two-paired mounds. More than 40 individuals were recovered, including three bundle burials: two of the burials represented two males while a third contained two heads, one male and one female. Analysis by Femenías and Sans (2000) found no significant differences in the material culture associated with the burials and argued against the restriction of high-status differentiation to a few individuals. Data from several excavations in the region also suggest that the upper parts of the mounds were built as a corporate burial facility designed to reinforce kinship, clan, or community ties rather than to mark the death of a single, important individual.

In addition, the application of systematic archaeobotanical analyses has changed how we view the economy of these groups and has been used to document the earliest adoption of cultigens in the region. At the Los Ajos site, plant and animal remains indicate the adoption of a mixed economy shortly after people began to live in more permanent villages. Phytolith and starch grain analyses of seeds, leaves, and roots from a variety of wild and domesticated species uncovered the earliest occurrence in the region of at least two domesticated crops: corn (Zea mays) and squash (Cucurbita spp.), which appeared shortly after 4750 cal yr BP (Iriarte et al. 2004). The close association between large mound complexes and the most fertile agricultural lands in the region suggests that people likely practiced flood-recessional farming during the preceramic mound period. During the spring and summer months, organic soils are exposed on the wetland margins; these superficial peat horizons are highly fertile, hold moisture, and are easy to till. In addition, the floodwater of the nearby Cebollatí River periodically inundates the area and replenishes the soils with nutrients. The India Muerta wetlands are thus an ideal location for wetland margin seasonal farming (Iriarte 2003, 2007; Iriarte et al. 2004). The exploitation of palms is evidenced by the recovery of palm nut endocarps from butia (Butia capitata) and pindó (Syagrus romanzoffiana), as well as by the presence of abundant globular echinate palm phytoliths in the basal preceramic mound period at Los Ajos, Isla Larga, and Estancia Mal Abrigo (Iriarte et al. 2001). Dense stands of oligarchic butia palm groves, whether wild, encouraged, or cultivated, constituted an extremely rich seasonal resource for prehistoric populations living in the area (López Mazz et al. 2014). Analyses from different sites in the southern sector of the Lagoon Merin basin and northeastern Uruguay dating back to 4750 cal yr BP also have expanded our knowledge of the use of wild plants including tubers (Canna glauca, Typha dominguensis, Cyperus sp. and Scirpus sp.) and bromeliads (Bromelia sp.), and of the possibly domesticated plants including beans (Phaseolus sp.) and peanuts (Arachis sp.) (e.g., Capdepont et al. 2005; Del Puerto 2015; Del Puerto and Inda 2005; López Mazz et al. 2014).

Given the formal design of community villages in the Early Formative societies of southeastern Uruguay and the elaboration of public architecture, the lack of archaeological correlates for personal ranking is remarkable. Absent are differential mortuary patterns, specialized craft production, exotic/prestige goods, and/or corporate architecture that may require a body of authority to mobilize and organize large labor pools; the power aspirations of individual political actors may not have been successful. It seems that rituals aimed at reinforcing kinship ties through communal rites neutralized any attempt of individual aggrandizement. These mechanisms may have effectively limited and undermined the degree of political control that the Early Formative group leaders could have maintained over their communities. The archaeological evidence shows that agent-based competitive strategizing activities, such as feasting (e.g., Clark and Blake 1994; Dietler 2001; Hayden 1995, 2001), long-distance exchange (e.g., Helms 1994), or warfare (e.g., Carneiro 1998; Redmond 1994, 1998) did not crystallize in the Early Formative societies of southeastern Uruguay, or at least are not archaeologically conspicuous. Consequently, it is best to conceptualize these Early Formative societies as group-oriented (Renfrew 1974), corporate (Blanton et al. 1996), communal social formations (Saitta 1997) that resisted individual aggrandizers in their path to power (e.g., Lee 1990; Wiessner 2002).

Sambaquis

Regional studies have been especially fruitful in enlightening the social landscapes of the Sambaqui builders of the Atlantic Coast. Recent research, focused on an area of roughly 692 km2 on the southern coast of Santa Catarina, around the Santa Marta Cape, has investigated the joint evolution of the landscape and the nature of the Sambaqui occupation (DeBlasis et al. 2007; Kneip 2004). Sambaqui builders have been settled around a bay/lagoon system for at least six millennia, with a considerable demographic expansion between approximately 5,000 and 2,000 years ago, seen both in the number of sites and their overall incremental size/volume. Settlement expansion displays a circum-lagoon distribution of site clusters marked by some long-lived mounds and smaller sites. This coeval distribution has been interpreted as face-to-face communities around the lake sharing an essentially aquatic way of life, but also accessing nearby firm-ground hinterland resources. The lack of evidence for centralized power, together with evidence for cultural homogeneity and social integration, sedentariness, and economic intensification, strongly suggests the emergence of a heterarchical social structure. The distribution of mounds dedicated to ancestors points to the sharing of the territory between well-tied social units, possibly related to local lineages.

The social glue, based on the sharing of cultural (and, over the southern shores, probably also linguistic) traits, seems to have been provided by a strong overall religious system structured around the cult of ancestors, with strong reciprocity ties among communities. These links seem to have promoted peace and social stability, as well as propitious conditions for intensifying resource production into and around the lagoon. Occasional outstanding burials suggest the possibility of the emergence of more centralized leadership, but they are rare and dispersed. Burial patterns are rather homogenous and do not show peculiarities that could be related to gender, age, or even social distinctions.

The nature of their construction also has played a major role in discussion about the complexity of these groups. These shell mounds consist of cultural deposits of varying sizes and stratigraphies, in which shell is a major constituent. These accumulated deposits undoubtedly reflect a range of formative processes. They consist of sequences of sand and shell deposition, both natural and artificial, mingled with darker, more organic layers; they often display features associated with activities that took place on older surfaces, subsequently buried within the mound. While single-layered small sambaquis may contain only a few artifacts and features, possibly representing campsites or processing stations, many others served mortuary functions (Fig. 5). This is the case, in particular, with the massive mounds found on the southern shores, which contain complex stratigraphic sequences (Gaspar et al. 2008). These larger shell mounds exhibit many alternating sequences of shell deposits and narrower, darker layers with plenty of charcoal and (often burnt) fishbone that mark successive occupation surfaces over the mound. The dark layers represent large funerary areas with clusters of burials, hearths, and postholes. Lithic and bone artifacts also are characteristic components of these dark layers, which consist mostly of secondary fill brought from other activity areas outside the funerary context with the purpose of covering the burials (Suárez Villagran et al. 2010). Despite abundant food refuse in the mounds and features (such as earth ovens) that would be expected in domestic contexts, recognizable dwelling areas have not been encountered, neither do the distribution and arrangement of features indicate sustained domestic activity.

Archaeologists now perceive the sambaquis as long-lived monumental structures located in permanent places, highly visible in coastal cultural landscapes, and drenched with symbolic meaning (Fish et al. 2013). This interpretation clashes with previous views that saw them as giant middens or platforms for dry, elevated residences in the context of domestic activities (e.g., Beck 1972; Hurt 1974; Kneip 1977; Prous 1992; Rohr 1984). The enduring and socially orchestrated effort necessary to create these huge mounds of shell (up to 50 m in height and 600 m in diameter) is certainly not casual or unintentional. Instead, it has created impressive landmarks in which the ancestors are embedded in long-lived sacred landscapes (DeBlasis et al. 1998, 2007; Fish et al. 2013; Gaspar 1998, 2000; Gaspar et al. 2008).

There are funerary areas concentrated in confined spaces in the sambaquis. The bodies are not disposed of at random but in special areas set aside for this purpose. The funeral ritual is elaborated and characterized by the deposition of artifacts restricted to the funeral space and associated with burials (Gaspar 1998; Gaspar et al. 2008). As the burials are placed in areas of intersection of stratigraphic layers, it can be argued that they are directly related to the construction events of the sambaquis, which are characterized by discrete mounded layers and lenses. Funerary structures are generally demarcated by postholes, hearths, and ash lenses, leading Klokler and Gaspar (2013) to argue that the bodies must have been suspended on wooden structures during funeral rites. It is also common to find closed Lucina pectinata shells in association with articulated parts of fish skeletons, such as in the Amourins sambaqui; these have been interpreted as burial offerings (Klokler and Gaspar 2013). Additionally, although there is some evidence of violence recorded in sambaqui skeletal remains, the number of individuals who suffered violent deaths is extremely low, which in turn suggests that warfare did not play a major role in intra- or intergroup relationships (Lessa, 2005; Lessa and de Medeiros 2001). Overall, Mendonça de Souza et al. (2013) conclude that the buried and their contexts are testimonies to the mound builders, the construction processes employed, and how these sites were used, including their symbolic aspects.

Our perception of the economy of these groups is also changing. Sambaquis have traditionally been seen as the remains of successive camping episodes left behind by mobile mollusk-gathering and fishing bands. Recent studies, however, have yielded increasing evidence in terms of demography, social organization, and long-term territorial stability for the presence of more complex communities based primarily in highly productive estuarine and lagoon environments (DeBlasis et al. 1998, 2007; Gaspar et al. 2008). Zooarchaeological studies (Figuti and Klokler 1996; Klokler 2008) and isotopic analyses of human bone (Colonese et al. 2014) have shown that the diet of these groups relied predominantly on fishing, supplanting the deep-rooted idea of a simple nomadic shellfish-gathering economy. Indeed, bone artifacts from sambaquis are compatible with net and hook fishing technologies (Figuti and Klokler 1996). Anthracological analysis of sambaquis on the Río de Janeiro coast by Scheel-Ybert (2001) allowed for the first time the documentation of the consumption of monocotyledon tubers (Dioscorea sp., Typha sp., Cyperaceae), which along with the presence of palm fruit shells and seeds attest to the importance of plants in the diet of Sambaqui people. Evidence for the use of vegetable food (Boyadjian 2012; Scheel-Ybert 2013) is also reinforced by a variety of stone grinding tools and mortars found in sambaquis. Skeletal studies reveal evidence for canoeing and diving, a lifestyle linked to aquatic environments (e.g., Okumura and Eggers 2005).

Collectively, the evidence gathered so far suggests that Sambaqui society of the southern shores evolved for several millennia during the mid-Holocene and more recently (between 5000 and 2000 cal yr BP), with a considerable demographic expansion occurring without visible changes in social organization patterns. Social and economic complexification seems to have led to the emergence of a rather heterarchical social structure, with no particular evidence for social hierarchy. Further research will clarify to what extent these long-standing cultural patterns were widespread and whether there are subtle social changes that are still unseen in this long sequence.

Pantanal

Regional studies of settlement patterns in the Pantanal show that mounds seldom occur in isolation. They are generally found in clusters forming a line along the margins of streams and rivers, and forming circular to semicircular arrangements along the perimeter of lagoons; they also occur in hundreds in the flooded marshes, creating forest islands. A visual inspection of the distribution map of Córrego das Pedras (Schmitz et al. 1998, p. 81) reveals how these sites exhibit mound clusters of varied spatial arrangements: this surely deserves further exploration and detailed topographical mapping. Mounds are generally elliptic or elongated in plan; they exhibit diameters of 20–100 m and heights of 1–3 m. Schmitz et al. (1998) observed that the majority of mounds are located in places where today’s floods do not cover the marshes more than 1.5 m; they concluded that the Pantanal pre-Columbian people took advantage of topographically higher locations like river levees to construct mounds, similar to the wetlands of the Paraná Delta (Bonomo et al. 2011a) and southeastern Uruguay (Iriarte 2006a).

Based on the seasonality of resources, the location of sites in the landscape, the thickness of archaeological layers, relative density of artifacts, and the composition of the faunal assemblages, Schmitz et al. (1998, 2009) have suggested that the Pantanal populations were highly mobile canoe foragers who left behind two different types of archaeological sites. On the one hand, central sites have larger, more permanently occupied habitation areas. They are located in central and more stable margins of the larger lagoons and river dykes and contain thicker stratigraphic layers, a higher density of archaeological artifacts, primary and secondary burials, and necklace beads; the faunal assemblage is mainly composed of fish, mammals, and birds. On the other hand, short-term, temporary sites were are located in seasonally flooded marshes and likely related to seasonal occupations. Shellfish and crustaceans dominate the faunal assemblages of these sites; they lack fish, reptile, mammal, and bird bones.

Mound stratigraphy is a combination of natural and cultural processes. In general, the base of the mound has a natural silty clay layer followed by a crusty calcareous concretion layer, on top of which the cultural layers were deposited. The heterogeneous cultural strata contain layers of shellfish, fish, bird, and mammal bones as well as charcoal and ash lenses, which has led the excavators to interpret the mounds as habitation sites. Site MS-MA-50 represents a typical example of this recurrent stratigraphic sequence (Schmitz et al. 1998, p. 152, fig. 57).

The Pantanal offers rich and abundant resources for human populations. Wetlands encompassing water bodies and adjacent wet prairies and marshes contain a great variety of fish resources (Siluriformes, Scianidae, Hoplias sp., Serrasalminae, among others), alligator (Caiman yacare), turtles (Chelidae), shellfish (Pomacea, Marisa), capybaras (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), giant otters (Pteronura brasiliensis), and marsh deer (Blastocerus dichotomus) as well as a great abundance of birds. An important plant resource, wild rice (Oryza latifolia), grows in wetland margins; it must have provided another abundant seasonal resource for pre-Columbian populations, as it did for historic groups. Levees and the adjacent escarpment provided wood, tree, and palm fruits, among many other resources. However, these rich resources are highly seasonal and unevenly concentrated throughout the year. During the flooding season fish disperse into the wetland shallow waters while animals find refuge in the forest islands. Shellfish, from the genera Pomacea and Marisa, living in the roots of the water hyacinth aguape (Eichhornia crassipes), are easy to collect at this time of the year. This period also marks the beginning of the planting season. As the dry season starts, fish resources begin to concentrate in the larger lagoons; the fruits of gravatá (Bromelia balansae), bocaiúva (Acrocomia sclerocarpa), amendoim-do-bugre (Sterculia apetata), acuri (Attalea phalerata), and other palm and fruit trees are ripe; and canoe travel is possible only in large lagoons and river channels. As the dry season comes to an end, wild rice and cultivars, such as maize, are ready to collect and harvest. Today, Guató indigenous populations plant squash (Cucurbita sp.), cotton (Gossypium sp.), sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas), yams (Dioscorea trifida), tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), manioc (Manihot esculenta), maize (Zea mays), and bananas (Musa spp.) as well as managing the acuri palm on the top of habitation mounds (De Oliveira 2000).

Southern Proto-Jê

Recent research shows that the southern Brazilian highlands were a highly structured landscape that revolved around funerary/ceremonial mound and causewayed enclosure complexes, usually located on hilltops or ridges commanding wide views. This distinctive range of monuments started to proliferate in the first half of the second millennium AD. Although recognized by early researchers (Ribeiro 1991; Rohr 1971), mound and enclosure complexes in the southern Brazilian highlands were not subject to intensive study. Locally called danceiros (dance grounds) in Brazil, they are characterized by circular, elliptical, rectangular, and keyhole-shaped earthworks whose rims are 30–80 cm tall, 3–6 m wide, and 20–180 m in diameter. They may exhibit or lack mounds and associated ringlets. Mounds are generally circular but can be rectangular platforms (e.g., SC-AG-12; DeMasi 2009); isolated large flat-top platforms have been documented around São José do Cerrito (Schmitz et al. 2013a), Lages, and Campo Belo do Sul localities (Fig. 6A).

Examples of Southern Proto-Jê earthworks: A, panoramic view of Abreu and Garcia mound complex showing circular bank (forefront), central mound (middle), and, wide viewshed; B, Houses 4 and 5 from the SC-CL-43 pit house village (Schmitz et al. 2010) showing the artificial low terrace around the houses on their downhill side.

In some regions, such as in El Dorado, Pinhal da Serra, Anita Garibaldi, and Campos Novos, mound and enclosure complexes occur together in groups, usually on the top of prominent hills that today exhibit wide view-sheds; several are positioned in relation to localized natural features such as rock outcrops that mark the highest spot of these hills (Iriarte et al. 2013; Saldanha 2008). However, these funerary structures also can be found in lower positions in the landscape, such as in the Urubici region (Corteletti 2012; Corteletti et al. 2015, p. 47, fig. 1).

Detailed topographical survey of complete plateaus and ridges has allowed a number of novel insights on the development of these site formations, revealing the complexity of sites through the number of alignments between different site types. For example, on the Avelino plateau in Pinhal da Serra (Iriarte et al. 2013), one linear arrangement at the site consists of three earthworks focused on the central mound of each mortuary earthwork (Fig. 7). A key nodal point in these alignments is a solitary pit house that forms the central point of three of the six identified alignments; it potentially identifies this as one of the most important points on the hill. Isolated pit houses associated with mound and enclosure complexes also have been documented at the Chico Carneiro site in Pinhal da Serra and at the Abreu and Garcia site (Campo Belo do Sul), where a linear alignment with the central mounds at the site has been identified. Possible interpretations are that these structures were utilized as part of ritual or ceremonial activity on the hill or that they housed a key person within that activity sequence.

Mound and enclosure complexes appear to be divided into two size categories, which probably relate to different uses of the structures (DeMasi 2009; De Souza and Copé 2011; Rohr 1971). Smaller rings, with a diameter of 10–40 m, are far more numerous; they are generally arranged in pairs, exhibit low and narrow rims, and most of them contain a shallow central mound or a pair of mounds. Smaller structures show dual architecture, a general southwest-northeast alignment, with larger structures located in the western section; these latter are always located in a slightly topographically higher position than the smaller structure (see Iriarte et al. 2013).

Larger rings, 70–180 m diameter, are fewer and exhibit higher, wider, and easily visible rims up to 1 m tall. Some of the large rings, like the one we have been investigating in El Dorado, Misiones, Argentina (Iriarte et al. 2008a, 2010), or site SC-CL-37 in Santa Catarina (Reis 2007) are more complex than a simple circle layout and include entry avenues and associated attached ringlets (Iriarte et al. 2010, p. 28, fig. 2).

Saldanha (2005, 2008) interpreted the small mound and enclosure complexes as likely village cemeteries. Following Adler and Wilshusen (1990), De Souza and Copé (2010) interpret small-paired mound and enclosure complexes as low-level integrative facilities built and visited by the inhabitants of nearby pit house villages. At these sites, the village inhabitants interred secondary inhumations and participated in collective funerary rites, reinforcing community ties. By contrast, large mound and enclosure complexes are interpreted as high-level social interaction facilities, whose construction involved the mobilization of labor from different communities dispersed across the region. More recently, Iriarte et al. (2013), drawing on the complementary asymmetry of historic Kaingang moieties, have suggested that the ritual separation of space in Southern Proto-Jê small-paired funerary structures, characterized by a larger mound and enclosure complex on the west side, may represent this dual ranked opposition.

Data from mound and enclosure complexes have provided one of the best avenues to discuss the complexity of the Southern Proto-Jê groups. For example, the SC-AG-12 mound complex consists of a pair of rings, Circle I and II, 30 m and 60 m in diameter, respectively (DeMasi 2006, 2009). The central mound of Circle I contains the cremated burial of an adult and an infant, and the central mound of Circle II contains six collective cremated burials. These cremated burials are accompanied by offerings including cups, food vessels, lip plugs, and ceramic figurines. In Circle I, in the area between the mound and the embankment, DeMasi (2006, 2009) excavated discrete stone clusters arranged in a crescent and facing the central mound, similar to the ones unearthed by Iriarte et al. (2008a, 2010) at the base of rim at the PM01 site in El Dorado Misiones. DeMasi (2009) argues that the two individuals, an adult and an infant, buried in the mound of the larger ring located on the western side of the site, had a higher social status than the six individuals buried collectively in the smaller ring of this site.

The excavation of such burial mounds and the analysis of the cremated human remains within them also has begun to reveal a diversity of funerary practices, including the cremation and burial of single or multiple individuals within pyres and the subsequent redeposition of cremated bone (Müller and Mendonça de Souza 2011; Ulguim 2015). These analyses show that the treatment of the dead comprised several different stages including, but not limited to, the cremation of human remains in funerary pyres. Remnants of funerary pyres have been found at the base of the mounds, notably the Avelino site, Structure 3A (DeMasi 2009; De Souza and Copé 2010) and the Anita Garibaldi sites (SC-AG-12, SC-AG-98-Structure 2) (Müller and Mendonça de Souza 2011). Redeposition of burned bone in “cremated deposits” is also common, both in small pits as well as on mound floors (Thompson and Ulguim, in press). Sometimes these practices are present within the same mound. At Pinhal da Serra, excavations at the central mound of Avelino Structure 3A show that it was built over the remains of a funerary pyre containing burned bone. In the same mound, in a separate context, a cremated deposit was uncovered, where the body had been cremated in another locality; the remains had been gleaned from the pyre and then collected, possibly in a basket, transported, and deposited in a pit that was later covered with earth, forming a mound (De Souza and Copé 2010, p. 111, figs. 5, 6; Ulguim 2015). In addition, patches of burnt earth with a few charcoal fragments have been identified on mounds, suggesting that these could be the pyre bases and ash beds of pyres where all the burned bone was gleaned and redeposited at another mound, as at Posto Fiscal and SC-AG-12 mounds (DeMasi 2009; Iriarte et al. 2013). Finds of small ceramic cups are characteristically associated with the interments and possibly indicate food offerings. The fragmented nature of the burned bones recovered in excavations makes it difficult to identify the age and sex of the deceased, but the type of fractures on bones suggest that bodies were cremated with soft tissues and that fire temperatures may have exceeded 650 °C (Müller and Mendonça de Souza 2011). At the burial cut feature of Avelino Structure 3A, aging evidence from the unfused distal tibial epiphysis indicates a probable subadult of 14–20 years old. At SC-AG-108 Enclosure 2, evidence for dental eruption indicates an age of greater than 21 years (Ulguim 2015, p. 202).

Other interesting features at mound and enclosure complexes are the assemblages of stone clusters. At site PM01 in El Dorado Misiones, eight stone clusters dating to circa AD 1250–1270 have been unearthed on the base of the western sector of the larger ring of the site (Iriarte et al. 2010, p. 31, fig. 6); they have been interpreted as earth ovens similar to the ones used during historic times (Paula 1924). Phytolith analysis from charred residues of four ceramic sherds associated with these stone clusters documents the presence of maize cob, suggesting these ceramics were used to drink maize-based beverages. Iriarte et al. (2008a, 2010) argue that the vast plaza area of Circle I at site PM01, the accumulated earth ovens, and their associated ceramics indicate that large numbers of participants came together regularly at this notable ritual structure to feast on meat delicacies and maize beverages as part of postburial funerary practices. Another collection of earth ovens forming a crescent-shaped spatial arrangement has been discovered in the sector between the rim and the central mound at the SC-AG-12 complex (DeMasi 2009). Single stone clusters also have been documented in mound floors at the Posto Fiscal site (Iriarte et al. 2013), again showing that these cooking structures were a common feature of mortuary sites and likely were associated with ritual feasting.

Finally, we also are beginning to understand the construction sequence of mound and enclosure sites and their architectural developments over time. Overall, excavated mounds from funerary structures associated with the Southern Proto-Jê groups are showing complex and diverse histories, ranging from the building of mounds as a single construction episode, as at the PR-UB-04 (Ubiratã) site (Chmyz and Sauner 1971), to the interments of several individuals in different episodes, as at the SC-AG-12 site (DeMasi, 2009). Detailed topographical survey and excavations at keyhole-shaped earthworks have revealed their construction history, showing a move from circular to rectilinear architectural shapes. For example, a rectangular annex was added to circular enclosures at the Reco and Posto Fiscal sites (Iriarte et al. 2013, p. 88, fig. 11), representing a movement toward more complex and diverse forms of architecture.

One of the most interesting aspects of the research on Southern Proto-Jê mound and enclosure complexes is that they reveal a clear connection between the archaeological record and ethnography. In fact, the southern Brazilian highlands are one of the few regions in the world where mortuary rituals associated with mound building are recorded in the European accounts of the 17th–19th centuries. Ethnographers subsequently investigated the Southern Jê groups during the 20th century (e.g., Baldus 1937; Becker 1976; Crépeau 1994; Henry 1964; Maniser 1930; Métraux 1946; Paula 1924; Veiga 2006). These groups exhibit dual social organization characterized by exogamic, patrilineal moieties. For the Kaingang, the moieties are complementary and also asymmetrical; the archaeological and ethnohistoric records suggest the presence of sizable, regionally organized, hierarchical societies (e.g., Crépeau 1994; Fernandes 2000). Importantly, funerary and postfunerary rituals are reported to be their single most important ceremony, when the entire group gathered together. These events included the burial of important chiefs, secondary burials, the inheritance of the chiefly office by the eldest son of the deceased chief, initiation rites, name-giving ceremonies, performance and recreation of the cosmogony myth, and feasting (e.g., Iriarte et al. 2008a, 2013; Maniser 1930; Métraux 1946; Silva 2001; Veiga 2006). The mound and enclosure complexes from the first half of the second millennium AD and the circumstances in which they arose are very different from the ones reported during the 17th–20th centuries. As we show below, there are many subjacent structures associated with the asymmetrical dual organization of these societies, and with the spatial segregation of ritual space and the alignment of burial mound and enclosures, that have endured during the historic times (see Iriarte et al. 2013). The connection also is exemplified at the Avencal rock art site in Urubici, which exhibits masks and faces with facial painting that could be related to Kaingang moieties. While some exhibit slim, tall, and open signs like the Kame moiety, others are characterized by circular, low, and closed motifs like the Kainru moiety (Riris and Corteletti 2015; Silva 2001).