Abstract

This paper presents a simple conceptual framework specifically tailored to measure individual perceptions of wage inequality. Using internationally comparable survey data, the empirical part of the paper documents that there is huge variation in inequality perceptions both across and within countries as well as survey-years. Focusing on the association between aggregate-level inequality measures and individuals’ subjective perception of wage inequality, it turns out that there are both a high correlation between the two measures and a considerable amount of misperception of the prevailing level of inequality. The final part of the analysis shows that subjective inequality perceptions appear to be more important, in a statistical sense, in explaining variation in individual-level attitudes toward social inequality than objective measures of inequality. This underlines the conceptual and practical importance of distinguishing between subjective perceptions of inequality and the true level of inequality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Such as the perception of inequality of opportunity (Brunori 2017), tax rates (Gemmell et al. 2004), the perception of corruption (Olken 2009), or individuals’ self-assessment of how their own well-being would change as a result of various life events (Odermatt and Stutzer 2018). One persistent and well-known finding relates to individuals’ (mis-)perception of probabilistic events (e.g., Dohmen et al. 2009).

Consistent with this line of reasoning, evidence is accumulating on behavioral and attitudinal spillovers from inequality from a diversity of contexts and based on either experimental (e.g., Clark et al. 2010; Card et al. 2012; Kuziemko et al. 2015) or non-experimental data (e.g., Clark et al. 2010; Cornelissen et al. 2011; Dube et al. 2019; Kuhn 2019; Pfeifer 2015). Moreover, a related literature, focusing on the effect of inequality on subjective measures of satisfaction or happiness, generally finds that higher inequality is associated with less satisfaction and/or lower happiness (e.g., Senik 2005; Verme 2011). Clark and D’Ambrosio (2015) provide a comprehensive survey of both experimental and survey evidence on individuals’ attitudes to income inequality.

The same data, or parts thereof, were used with a similar purpose by several previous studies (e.g., Jasso 1999; Niehues 2014; Osberg and Smeeding 2006), but all of these studies used different frameworks to measure individuals’ inequality perceptions. See also Knell and Stix (2017), who compare different conceptualizations of inequality perceptions.

The data are available to researchers from the GESIS data archive (http://www.gesis.org). More information about the ISSP is available from the organization’s website (http://www.issp.org). Note that the cumulation file contains a harmonized list of variables, but that it does not cover all of the countries taking part in the separate waves of the survey.

Moreover, while most respondents were asked to estimate earnings before taxes, respondents in a few realizations of the survey were asked to estimate wages after taxes. This further complicates any simple comparison between the two measures. In the empirical analysis below, however, the inclusion of country and survey-year fixed effects will largely eliminate this issue. Another issue is that the questions in the ISSP module implicitly refer to full-time workers only, while objective inequality measures cover both full- and part-time workers.

Kuhn (2013) provides kind of a validity check of the framework, showing that the framework is able to capture plausible differentials in inequality perceptions between (former) East and West Germany, consistent with evidence from other, independent sources of data (Alesina and Fuchs-Schündeln 2007).

The two population shares are treated as fixed parameters, even though it is easy to imagine that individuals have different (and potentially biased) perceptions of these quantities as well; see Evans and Kelley (2004), for example. This contrasts with other frameworks used in the literature which rely on individuals’ estimates of relative group sizes (e.g., Engelhardt and Wagener 2014; Gimpelson and Treisman 2018; Niehues 2014). As mentioned in Introduction, the findings from Eriksson and Simpson (2012) and Chambers et al. (2014) suggest that the extent of inequality individuals perceive might differ, depending on whether the measurement is based on individuals’ estimates of wages and/or relative group sizes.

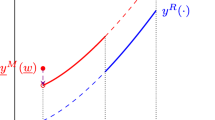

In principle, and in contrast to the Gini coefficient describing the objective distribution of wages, the subjective Gini coefficient given by Eq. (4) can take on negative values because some individuals may believe that \({\overline{y}}^{\mathrm{bottom}}> {\overline{y}}\), which would imply that the perceived wage share of the bottom group is larger than their actual population share. (That is, \(q_{i}^{\mathrm{bottom}}\) can take on any value between zero and one.) Empirically, as shown in Table 1, this is true for a small fraction of the overall sample (less than 0.4% of the overall sample).

Estimated group shares do not change much over time, and thus, the results would hardly change if I only were to allow the population shares to vary across countries (but not over time within a given country). There are, however, substantial differences in \(f_{\mathrm{bottom}}\) across countries.

While it is possible to include a full set of country \(\times \) survey-year fixed effects, note that the fixed effects will fully pick up any potential effect of aggregate-level inequality on inequality perceptions (i.e., it is not possible to estimate both a full set of fixed effects and the effect of any aggregate-level variable). Nonetheless, estimating such a specification is useful as a robustness check, as discussed in Sect. 5.4 below.

“Online Appendix Table B.5” reports estimates using alternative measures of individual-level inequality perceptions in place of the baseline subjective Gini coefficient.

The exact wording of the corresponding items is as follows: (i) “Income differences in (respondent’s country) are too large” (five possible answer categories, ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”), (ii) “Government should reduce income differences” (with the same possible answers as in (i)), and (iii) “Should people with high incomes pay more taxes” (five possible answers, ranging from “much larger share” to “much smaller share”).

As a simple robustness check, I also estimated similar regressions using binary variables (indicating a respondent’s agreement with the underlying survey item) as dependent variables, yielding qualitatively identical results. Moreover, estimation by ordered probit also yields qualitatively identical results. These additional estimates are shown in “Appendix” Table 7.

Mean inequality perceptions are only marginally influenced by individual inequality perceptions, but one might argue that a respondent’s perception of wage inequality is influenced by the perceptions of people around him or her (for example his or her colleagues at work). One potential issue with this instrument is that there might be a direct (positive) effect on individuals’ attitudes, which would bias the 2SLS estimates (upward). On the other hand, the results from “Online Appendix Table B.3” suggest that regional differences (within countries) in inequality perceptions do not appear to be especially relevant, conditional on country and survey-year fixed effects.

I also estimated the models using both instruments at the same time and based on different estimation methods (see “Appendix” Table 9). Overall, the resulting point estimates are close to the 2SLS estimates from Table 5. Moreover, I cannot reject the null hypothesis that the overidentifying restrictions are valid in two out of three cases, supporting the credibility of the 2SLS estimates.

For each of the three outcomes of Table 4, I also estimated a regression specification including a full set of country \(\times \) survey-year fixed effects (see, again, “Appendix” Table 8). In each case, the estimates turn out very similar to those from Table 4, further strengthening the case that attitudes toward inequality are primarily driven by the perception of inequality, rather than by the true level of inequality.

Moreover, the finding of such a close association between inequality perceptions and aggregate-level inequality, using entirely independent sources of data, shows that simple survey items are sometimes surprisingly powerful indicators of even complex economic phenomena.

References

Alesina A, Angeletos G-M (2005) Fairness and redistribution. Am Econ Rev 95(4):960–980

Alesina A, Fuchs-Schündeln N (2007) Good-bye Lenin (or not?): the effect of communism on people’s preferences. Am Econ Rev 97(4):1507–1528

Bavetta S, Li Donni P, Marino M (2019) An empirical analysis of the determinants of perceived inequality. Rev Income Wealth 65(2):264–292

Bénabou R, Tirole J (2006) Belief in a just world and redistributive politics. Q J Econ 121(2):699–746

Brunori P (2017) The perception of inequality of opportunity in Europe. Rev Income Wealth 63(3):464–491

Cameron AC, Miller DL (2015) A practitioner’s guide to cluster-robust inference. J Hum Resour 50(2):317–372

Card D, Mas A, Moretti E, Saez E (2012) Inequality at work: the effect of peer salaries on job satisfaction. Am Econ Rev 102(6):2981–3003

Chambers JR, Swan LK, Heesacker M (2014) Better off than we know distorted perceptions of incomes and income inequality in America. Psychol Sci 25(2):613–618

Clark AE, D’Ambrosio C (2015) Attitudes to income inequality: experimental and survey evidence. In: Handbook of income distribution, vol 2A, chapter 13, North-Holland, pp 1147–1208

Clark AE, Masclet D, Villeval MC (2010) Effort and comparison income: experimental and survey evidence. Ind Labor Relat Rev 63(3):407–426

Cornelissen T, Himmler O, Koenig T (2011) Perceived unfairness in CEO compensation and work morale. Econ Lett 110(1):45–48

Cowell FA (2000) Measurement of inequality. Handb Income Distrib 1:87–166

Cruces G, Perez-Truglia R, Tetaz M (2013) Biased perceptions of income distribution and preferences for redistribution: evidence from a survey experiment. J Publ Econ 98:100–112

Di Tella R, Galiani S, Schargrodsky E (2007) The formation of beliefs: evidence from the allocation of land titles to squatters. Q J Econ 122(1):209–241

Dohmen T, Falk A, Huffman D, Marklein F, Sunde U (2009) Biased probability judgment: evidence of incidence and relationship to economic outcomes from a representative sample. J Econ Behav Organ 72(3):903–915

Dube A, Giuliano L, Leonard J (2019) Fairness and frictions: the impact of unequal raises on quit behavior. Am Econ Rev 109(2):620–63

Engelhardt C, Wagener A (2014) Biased perceptions of income inequality and redistribution. Working paper no. 4838, CESifo

Eriksson K, Simpson B (2012) What do Americans know about inequality? It depends on how you ask them. Judgm Decis Mak 7:741–745

Evans MD, Kelley J (2004) Subjective social location: data from 21 nations. Int J Publ Opin Res 16(1):3–38

Fuller M (1979) The estimation of Gini coefficients from grouped data: upper and lower bounds. Econ Lett 3(2):187–192

Gastwirth J, Glauberman M (1976) The interpolation of the Lorenz curve and Gini Index from grouped data. Econometrica 44(3):479–483

Gemmell N, Morrissey O, Pinar A (2004) Tax perceptions and preferences over tax structure in the united kingdom. Econ J 114(493):F117–F138

Gimpelson V, Treisman D (2018) Misperceiving inequality. Econ Polit 30(1):27–54

Giuliano P, Spilimbergo A (2014) Growing up in a recession. Rev Econ Stud 81(2):787–817

Gründler K, Köllner S (2017) Determinants of governmental redistribution: income distribution, development levels, and the role of perceptions. J Comp Econ 45(4):930–962

ISSP Research Group (2014a) International social survey programme: social inequality I–IV-ISSP 1987–1992–1999–2009. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne, ZA5890 Data File Version 1.0.0

ISSP Research Group (2014b) International social survey programme: social inequality I–IV add on—ISSP 1987–1992–1999–2009. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne, ZA5891 Data file Version 1.1.0

Jasso G (1999) How much injustice is there in the world? Two new justice indexes. Am Sociol Rev 64(1):133–168

Kakwani N, Podder N (1973) On the estimation of Lorenz curves from grouped observations. Int Econ Rev 14(2):278–92

Kelley J, Evans M (1993) The legitimation of inequality: occupational earnings in nine nations. Am J Sociol 99(1):75–125

Kluegel JR, Smith ER (1981) Beliefs about stratification. Annu Rev Sociol 7:29–56

Knell M, Stix H (2017) Perceptions of inequality. Working paper, Austrian Central Bank

Kuhn A (2011) In the eye of the beholder: subjective inequality measures and individuals’ assessment of market justice. Eur J Polit Econ 27(4):625–641

Kuhn A (2013) Inequality perceptions, distributional norms, and redistributive preferences in East and West Germany. Ger Econ Rev 14(4):483–499

Kuhn A (2017) International evidence on the perception and normative valuation of executive compensation. Br J Ind Relat 55(1):112–136

Kuhn A (2019) The subversive nature of inequality: subjective inequality perceptions and attitudes to social inequality. Eur J Polit Econ (forthcoming)

Kuziemko I, Norton MI, Saez E (2015) How elastic are preferences for redistribution? Evidence from randomized survey experiments. Am Econ Rev 105(4):1478–1508

Loveless M, Whitefield S (2011) Being unequal and seeing inequality: explaining the political significance of social inequality in new market democracies. Eur J Polit Res 50(2):239–266

Mijs JJ (2019) The paradox of inequality: income inequality and belief in meritocracy go hand in hand. Soc Econ Rev (forthcoming)

Moulton B (1990) An illustration of a pitfall in estimating the effects of aggregate variables on micro units. Rev Econ Stat 72(2):334–338

Niehues J (2014) Subjective perceptions of inequality and redistributive preferences: an international comparison. Working paper, Cologne Institute for Economic Research

Norton MI, Ariely D (2011) Building a better America—one wealth quintile at a time. Perspect Psychol Sci 6(1):9–12

Odermatt R, Stutzer A (2018) (Mis-) predicted subjective well-being following life events. J Eur Econ Assoc 17(1):245–283

Ogwang T (2003) Bounds of the Gini Index using sparse information on mean incomes. Rev Income Wealth 49(3):415–423

Olken B (2009) Corruption perceptions versus corruption reality. J Publ Econ 93(7–8):950–964

Osberg L, Smeeding T (2006) “Fair” inequality? Attitudes toward pay differentials: The United States in comparative perspective. Am Sociol Rev 71(3):450–473

Oto-Peralías D (2015) The long-term effects of political violence on political attitudes: evidence from the Spanish civil war. Kyklos 68(3):412–442

Petrova M (2008) Inequality and media capture. J Publ Econ 92(1):183–212

Pfeifer C (2015) Unfair wage perceptions and sleep: evidence from German survey data. Schmollers Jahrb 135(4):413–428

Schneider SM (2012) Income inequality and its consequences for life satisfaction: What role do social cognitions play? Soc Indic Res 106(3):419–438

Schneider SM, Castillo JC (2015) Poverty attributions and the perceived justice of income inequality: a comparison of East and West Germany. Soc Psychol Q 78(3):263–282

Senik C (2005) Income distribution and well-being: What can we learn from subjective data? J Econ Surv 19(1):43–63

Solt F (2015) On the assessment and use of cross-national income inequality datasets. J Econ Inequal 13(4):683

Solt F (2016) The standardized world income inequality database. Soc Sci Q 97(5):1267–1281

Trump K-S (2018) Income inequality influences perceptions of legitimate income differences. Br J Polit Sci 48(4):929–952

Verme P (2011) Life satisfaction and income inequality. Rev Income Wealth 57(1):111–127

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

I thank two anonymous referees for many thoughtful and constructive comments and Sally Gschwend-Fisher for proofreading the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Additional tables

Additional tables

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kuhn, A. The individual (mis-)perception of wage inequality: measurement, correlates and implications. Empir Econ 59, 2039–2069 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01722-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01722-4

Keywords

- Inequality perceptions

- Inequality

- (Mis-)perceptions of socioeconomic phenomena

- Attitudes toward social inequality