Abstract

The vibrational energy of crystals is known to propagate in a fixed number of phonon branches allowed by symmetry. In the realm of nonlinear dynamics, however, additional nonlinear propagating modes are possible. Nonlinear propagating modes have unique properties that are important in many disciplines including optical communications, conducting polymers, biology, magnetism, and nuclear physics. Yet, despite the crucial importance of crystal lattice vibrations in fundamental and applied science, such additional propagating modes have not been observed in ordinary crystals. Here, we show that propagating modes exist beyond the phonons in fluorite-structured thoria, urania, and natural calcium fluoride using neutron scattering and first-principles calculations. These modes are observed at temperatures ranging from 5 K up to 1200 K, extend to frequencies 30–40% higher than the maximum phonon frequency, and travel at velocities comparable to or higher than the fastest phonon. The nonlinear origin of the modes is explained in part via perturbation theory, which approximately accounts for nonlinearity. Given that these modes are still clearly observed at 5 K, they are likely an inherent feature of the quantum ground state. The existence of these waves in three-dimensional crystals may have ramifications for material properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The study of lattice dynamics continues to play a key role in the development of modern materials including thermoelectric materials1, nuclear fuels2, and solar cell materials3, among many others. Thermal properties up to high temperatures are of particular interest for nuclear fuel materials such as ThO2 and UO2, with thermal properties impacting reactor performance and safety, and some next-generation reactor designs operating above 1000 K4. The dispersion relation of the phonons may determine a variety of properties, including phase stability and elasticity. Phonon interactions give rise to finite phonon lifetimes, and including these effects perturbatively5,6 may account for a larger number of properties, including thermal transport and thermal expansion7. However, some of the most interesting effects cannot be handled perturbatively, and strong nonlinearity must be directly accounted for.

A foundational study of nonlinear systems by Fermi, Pasta, and Ulam (FPU or Fermi–Pasta–Ulam) considered a one-dimensional lattice of particles coupled by nonlinear springs8. This simulation was expected to tend towards an equipartition of energy among all degrees of freedom after a large number of time steps, demonstrating the ergodicity of the system. Instead, they found energy moving between degrees of freedom, remaining unevenly distributed at any time scale, in what is now known as the FPU recurrence phenomenon9. Some complex nonlinear systems can be chaotic or very complex and are expected to be ergodic. However, some nonlinear systems like the FPU simulation form coherent nonlinear structures and traveling waves. This is because these simulations are below a stochasticity threshold, but still exhibit nonlinear dynamical structures beyond perturbed harmonic modes. A solitary traveling wave solution known as a soliton is the prototypical coherent structure seen in many macroscopic nonlinear systems10.

Although nonlinear traveling waves are well established in one-dimensional lattices, they have not been directly observed in one of the most commonly studied systems: three-dimensional crystal lattices. There is some evidence that crystals support anharmonicity-driven intrinsic localized modes (ILMs)11, which are stationary vibrations confined to just a few atoms. However, ILMs have only been observed at certain high temperatures and are sensitive to small changes in conditions12,13. Here we report the observation of robust nonlinear propagating modes (NPMs) in a common crystal lattice structure, the fluorite structure. These modes are observed at all temperatures measured—ranging from 5 K to 1200 K—and in all three fluorite-structured materials measured. The modes appear at energies above 60 meV and temperatures down to 5 K, demonstrating that they are not thermally generated, and they are inherently induced via the quantum zero-point motion. These nonlinear modes are always present and should be observable in the quantum mechanical ground state. Furthermore, it is likely that some features of fluorite structure are essential to the observation of these modes.

Results

Inelastic neutron scattering results

Time-of-flight inelastic neutron scattering measurements were performed using the wide Angular Range Chopper Spectrometer (ARCS) at the Spallation Neutron Source at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. A large (1.48 g) sample of ThO2 was grown by hydrothermal growth15 (see Methods for sample growth details), with μ-Raman measurements and time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (presented in Supplementary Note 1) characterization to ensure the crystal quality, resulting in crystals of equivalent quality to previous growths. Inelastic scattering results are compared to density functional theory (DFT) calculations of the phonons in Fig. 1 (see Methods for details of DFT calculations). There is general agreement with previous DFT results16, as well as current and previous inelastic neutron scattering results14 for the phonon modes. Phonons with different polarizations are measured separately in different scattering geometries (Supplementary Note 2). Additional scattering from the new mode is shown at energies higher than the highest phonon mode. The additional scattering is highlighted in the color contour plots shown in Fig. 1b–e. The middle panels (b, c) show the data along the [0,0,L] direction, integrated across a large range in [H,H,0] with the longitudinal optic modes (LO1 and LO2) visible. Additional scattering above the LO2 mode, from approximately 76 to 93 meV, is also visible at both 750 K (left) and 5 K (right). The two bottom panels (d, e) show constant energy plots as a function of two crystallographic directions, [0,0,L] and [H,H,0]. The lower left panel (d) shows the top of the LO1 mode, which does not significantly disperse in the [H,H,0] direction. The new mode scattering shares this geometry, as shown in the lower right panel (e).

a The dispersion of ThO2 is plotted along the three principal axes. Our current results are shown as open points, with previous triple-axis spectrometer data shown as closed points14 and our Density Functional Theory (DFT) results shown as stars for calculated points, and lines for the Fourier interpolation between the points. Longitudinal modes are shown as triangles, with transverse modes shown as circles. For many points, the error bar is smaller than the data point. Error bars represent one standard deviation. The new intensity is shown as pink, half-filled diamonds. With N = 3 atoms in the unit cell, 3N = 9 modes are numbered along the [ζζ0] direction where modes are not degenerate. The images to the right show the Brillouin zone, and the structure in real space. b, c The scattered neutron intensity as a function of energy and the [0,0,L] direction in reciprocal lattice units (r.l.u.), for 750 K and 5 K. The scattered intensity is indicated by a color scale, to the right of each figure. The perpendicular direction, [H,H,0], has been integrated over a large range and includes several Brillouin zones. As a result, several modes are visible simultaneously and across a range of energies if they disperse in [H,H,0]. The first Longitudinal Optic (LO1) mode does not disperse in [H,H,0] and is clearly visible from approximately 30 to 60 meV with a sinusoidal shape. Above the highest energy phonon is the new scattering intensity labeled as the Nonlinear Propagating Mode (NPM). d, e Constant energy slices as a function of [0,0,L] and [H,H,0] for the 750 K measurement. The top of the LO1 mode is shown on the left. It does not change as a function of [H,H,0], indicating that the LO1 mode does not disperse much along that direction. As a result, integration along [H,H,0] does not change the shape observed in b and c. At very high energies, 86 to 91 meV far above the highest phonon energy, the NPM is visible as shown on the right, with the same geometry as the LO1 mode in reciprocal space.

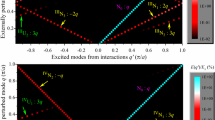

To help identify the origin of the dispersive mode above 76 meV we start by ruling out potential trivial explanations including a missed phonon, multiphonon scattering, multiple scattering, or a new unknown phase with high energy phonons. First, the number of phonon branches is fixed at three times the number of atoms in the primitive cell17, for a total of nine modes in fluorite, and all nine phonon modes have been accounted for below 76 meV (Fig. 1a). Independently, first-principles DFT calculations made in the harmonic approximation also account for all the phonon modes below 76 meV (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, the dielectric properties18 along with the Lyddane–Sachs–Teller relation and energy of the TO2 mode can be used to calculate the LO2 mode at Γ, and provide an independent measurement of the highest energy phonon at the Γ point. Next, two-phonon or higher order multiphonon scattering processes are strongly temperature dependent and should vanish at low temperatures (see Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 10); yet this mode persists at about the same relative intensity as the phonons on cooling from 750 K (Fig. 1b) to 5 K (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, while one-phonon scattering depends on the square of the neutron momentum transfer Q2, multiphonon scattering processes scale as Q4 (two-phonon) or higher19, and this high-energy mode exhibits the same Q2 dependence as a phonon (Fig. 2). Multiphonon scattering processes are also generally diffuse in both Q and E, while this mode is sharp in both Q and E. Finally, multiple independent scattering events (multiple scattering) generally do not follow the crystal symmetry and depend strongly on the incoming neutron energy Ei20,21 (see Supplementary Note 4).

a The incoming energy Ei = 140 meV neutron scattering data of ThO2 shown for the first Longitudinal Optic (LO1) mode as blue circles and the Nonlinear Propagating Mode (NPM) multiplied by a factor of 3 as red circles. The LO1 mode and the NPM are plotted as a function momentum transfer Q along the [0,0,L] direction, with a dotted green line indicating Q2 behavior. A range of [H,H,0] = [0, 4] reciprocal lattice units (r.l.u.) is integrated to produce the two plots, with energy ranges E = [58, 60] meV for the LO1 mode and E = [89, 91] meV for the NPM. Error bars represent one standard deviation. b The scattering intensity for a single quasiparticle excitation depends on Q as Q2, and the ratio of the NPM peak area and the LO1 peak area is plotted. The NPM and LO1 share the same Q dependence, and the quotient of the two mode intensities does not change as a function of Q. c Scattering intensity as a function of temperature is shown for the Transverse Acoustic (TA) mode and d the NPM. The dotted lines indicate how scattering intensity scales with temperature, which depends on the phonon population and energy, multiplied by a scale factor.

We have measured ThO2 at two different values of Ei (Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Fig. 5) and observed the new scattering repeating through at least three full Brillouin zones in the plane and in the out-of-plane detectors (Supplementary Fig. 6). Multiple scattering, which generally does not conform to crystal symmetry, can be the result of large crystal samples or scattering from the sample environment equipment. We have observed that this new signal does not change when observed with multiple different crystals of varying sizes and in different sample environment setups. An additional phase, with its own set of phonons, could also produce a high-energy mode, but a new phase would also produce Bragg peaks, which scatter much stronger than phonons and would be visible in addition to the expected peaks we observed. No new Bragg peaks have been observed beyond the peaks predicted for the flourite crystal structure. We have thus found that this scattering does not conform to any known artifact and instead exhibits the properties of a novel, single scattering event vibrational excitation. This excitation propagates within the lattice in addition to the harmonic (linear) modes. Hence, we refer to this new mode as a NPM.

NPM properties

The geometry of the NPM is similar to that of the LO1 mode, shown in the lower panels (d, e) of Fig. 1. Intensity as a function of two primary crystallographic directions, [H,H,0] and [0,0,L], is plotted for a given range in energy. For the LO1 mode, a narrow energy range of 58–60 meV, encompassing the very top of the LO1 mode at the Γ point was used. The corresponding color contour plot Fig. 1d shows the top of the LO1 mode at all odd values of [0,0,L], with no change as a function of H in the [H,H,0] direction, which allowed the integration in Fig. 1b,c. A wider energy range was used for the less intense NPM, shown in Fig. 1d, which still includes the high energy portion of the visible dispersion around the Γ point. The top of the NPM also exists on the odd values of [0,0,L], with at least three repetitions visible in this data set centered at [0,0,L] for L = 5, 7, and 9. This is additional evidence that periodicity of the propagating NPM matches the crystal structure, since it repeats from zone to zone. The NPM also shows no change in the perpendicular [H,H,0] direction. With a flat dispersion in the [H,H,0] direction, the NPM can be integrated over a large range in [H,H,0] to increase the intensity of the mode and produce the two middle panels of Fig. 1. Generally, phonons have a strong dependence along any crystallographic direction, and an integration of this type would integrate a mode as it disperses in [H,H,0] resulting in the mode’s intensity spreading over a large range in energy. However, the geometry of the LO1 phonon and NPM, unchanging with [H,H,0], allows for an integration along this direction without losing details of the LO1 mode or the NPM.

Single-phonon scattering intensity increases with Q as Q2. This is shown for the LO1 mode in Fig. 2. However, this Q dependence is not limited to strictly phonons. Any single quasiparticle scattering from the nucleus which is the result of atomic displacements will follow this Q dependence19, including scattering from the NPM. Higher order scattering processes will follow a different Q dependence (Q4, Q6, ...), and magnetic scattering will also follow a different Q dependence based on the magnetic form factor. This is also shown in Fig. 2 for the three visible peaks of the NPM which also follow a Q2 behavior. In addition to the Q dependence, the intensity of the NPM follows the temperature dependence of a phonon mode, shown in the lower two panels in Fig. 2. A general phonon-like temperature dependence described by the Bose occupation factor, n(ω, T) + 1, adjusted by an overall scale factor, is shown along with the temperature dependence of the TA mode and NPM.

From the dispersion behavior deduced from Fig. 1 we see that the LO1 phonon and NPM propagate strictly along the [0,0,L] direction (equivalently [L,0,0] and [0,L,0]) in what look like plane waves in reciprocal space. Since planes in reciprocal space correspond to rods in real space, this dispersion behavior indicates quasi-one-dimensional propagation along these directions in real space. Interestingly, nonlinear modes such as solitons and cnoidal waves form most readily in lower dimensions22.

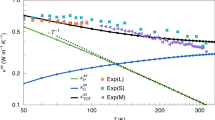

To check if the NPM exists in other fluorite structured materials, additional measurements were performed on fluorite structured UO2 and CaF2 using ARCS. Measurements on a UO2 single crystal, which was previously measured using a neutron triple-axis spectrometer23, were made at 600 and 725 K. A naturally grown geologic single crystal of the titular mineral fluorite, CaF2, was also measured at 5 K. The phonon dispersion curves of both materials have been previously measured using triple-axis spectrometers and simulated with a variety of techniques, including DFT23,24,25,26. We find evidence of an NPM in both samples, as shown in Fig. 3. There is a notable difference between the actinide oxide samples and the CaF2. The peak of the NPM dispersion in the CaF2 is shifted from the zone centers, where the LO1 maximum in energy is located, to the zone boundaries, where the LO1 minimum in energy is located (detailed description in Supplementary Note 5). The CaF2 also supports the NPM up to higher energy relative to the maximum phonon energy. The higher energy allows for more of the NPM dispersion to be visible in this material.

a, b Inelastic neutron scattering results in two additional fluorite structured materials, UO2 and CaF2. The scattering intensity as a function of [0,0,L] and energy is shown, with integration across a large range in [H,H,0]. The highest phonon energy from the second Longitudinal Optic (LO2) mode in both materials is shown as an orange dotted line. The scattered intensity is indicated by the color scale. c, d The intensity of the Nonlinear Propagating Mode (NPM) as a function of [0,0,L] and [H,H,0] is shown across an energy range indicated in the figure. Three reciprocal zones have a visible NPM in UO2, with the maximum energy occurring at the same location in reciprocal space as the maximum of the first Longitudinal Optic (LO1) mode, at odd values of L (L = 5, 7, and 9 reciprocal lattice units (r.l.u.) are visible). However, in CaF2 the maximum energy is not the same between the NPM and the LO1 mode, with the maximum of the LO1 mode occurring at odd values and the NPM maximum occurring at even values of L. The most visible NPM in CaF2 occurs at L = 8 r.l.u. as shown in d, which corresponds to a minimum of the LO1 mode. Additional maxima are visible at L = 4 and L = 6 r.l.u.

Discussion

From Figs. 1 and 3 we see that the NPM is supported in systems with varying mass ratios, interatomic force constants, and across a large range of temperatures. However, the fluorite structure is shared between these three samples and the NPM shares the quasi-one-dimensional geometry with the LO1 mode across all measurements. A number of flourite structures and dispersions have been established in the literature, with the LO1 mode sharing many common features across all structures. It seems likely that an NPM is supported in all fluorite structures as well.

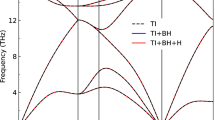

The existence of the NPM well above the phonon energies can be understood in part by examining q = Γ, where we see that the frequency of the NPM is very close to the sum of the TO2 and LO1 modes in all three materials (recall that LO1 and TO1 are degenerate). This experimental observation can be rationalized at the level of the single particle Green’s function, where the creation of a new peak in the imaginary portion (i.e., the vibrational spectral function) would require a new peak in the self-energy at the frequency of the NPM. Leading order perturbation theory5 at T = 0 dictates that there would need to be both a sufficient peak in the two-phonon density of states and a cubic interaction which links the three respective phonons. With regard to the latter, the Hamiltonian at q = Γ contains a cubic space group irreducible derivative of the form \({d}_{\Gamma \ \ \Gamma \ \ \Gamma }^{{T}_{1u}{T}_{1u}{T}_{2g}}\)27,28, where the T1u states give rise to TO2+LO2 and T2g correspond to LO1+TO1, so there is a nonzero cubic interaction which will link TO2 and LO1. Furthermore, both TO2 and LO1 are associated with appreciable peaks in the phonon DOS (Supplementary Note 6), which will result in a peak in the two phonon DOS at q = Γ. Therefore, we have a preliminary understanding of how the NPM emerges. However, a detailed understanding of the NPM and its dispersion, which behaves qualitatively different in CaF2 versus the other two systems, will require a full computation of the cubic interactions and evaluation of the scattering function.

It is also useful to draw a parallel with the Toda lattice22,29,30,31, a one-dimensional lattice with an exponential interatomic potential. The Toda potential supports both the standard linear phonon mode, as well as an additional lattice cnoidal wave mode based on the Jacobian cn function. Propagating modes with the cnoidal waveform may be considered solitons which are well-known outside of single-crystal systems. Lattice cnoidal waves are periodic with the reciprocal lattice periodicity and are of higher energy than the linear sinusoidal modes. Cnoidal waves therefore share the same fundamental properties of the NPM we have observed. They differ from the more common sinusoidal wave solution in real space, with more narrow peak heights surrounded by larger, flatter regions between the wave peaks in real space. In the continuum limit the Toda potential and lattice cnoidal wave solution becomes the well-known Korteweg–de Vries equation with macroscopic cnoidal wave solutions. More generally, additional modes such as the ILM or NPM that arise from nonlinearity are not strictly limited to one mode, and there may be additional NPMs beyond the single mode observed here.

Conclusion

We have measured and simulated the lattice dynamics in three fluorite structured materials. The phonon modes are observable by inelastic neutron scattering and in agreement with simulation. In addition to the full set of phonons, a nonlinear lattice mode is visible at energies above the highest energy phonon. This NPM retains the lattice periodicity and is visible in all fluorite structures measured, from a base temperature of 5 K up to 1200 K. Given that the mode is present at 5 K, our work calls for a detailed understanding of the quantum mechanical vibrational ground states in these materials. Furthermore, it will be imperative to understand how the NPM may affect various thermodynamic and transport observables.

Methods

Crystal growth

For this study, a ThO2 single crystal was fabricated by the hydrothermal growth method15. A feedstock of 15.476 g of ThO2 was placed in the bottom section of a 0.75 in.- silver reaction vessel/tube. A silver seed rack, which suspended a ThO2 seed crystal in the upper section of the tube, was inserted into the vessel. A silver baffle with a 15% porosity was also attached to the seed rack directly between the feedstock and seed zones. Once a mineralizer solution of 35 mL of 6M cesium fluoride was added to the vessel it was welded shut. The sealed silver vessel and 135 mL of counter pressure water was placed into a 250 mL Inconel autoclave. External band heaters affixed to the autoclave heated the feedstock and seed zones to 650 and 600 ∘C, respectively. This generated 26 kpsi of pressure inside of the vessel. These conditions were maintained for 60 days before the autoclave was cooled and the contents of the silver vessel were retrieved. A section measuring nominally 18.92 × 9.69 × 0.85 mm of the newly grown ThO2 was cut away from the seed crystal and used for the neutron scattering measurements. A second smaller section was also cut away and utilized for the ToF-SIMS measurements. Raman and ToF-SIMS characterization measurements are available in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Note 1). The elastic scattering collected during this experiment confirms the fluorite crystal structure across all temperatures (Supplementary Note 7).

DFT calculation of phonons

DFT calculations within the Generalized Gradient Approximation32 were performed using the Projector Augmented Wave method33,34, as implemented in the VASP code35,36,37,38. A plane wave basis with a kinetic energy cutoff of 400 eV was employed. We used a Γ-centered k-point mesh of 20 × 20 × 20. The crystal structure was relaxed, yielding a cubic lattice constant of 5.62018 Å. Phonons were computed using the Lone Irreducibe Derivarive approach27, which is a central finite difference approach that individually computes each group of theoretically allowed irreducible derivative within the smallest supercell possible. All irreducible derivatives within a 4 × 4 × 4 supercell were computed, though each derivative was extracted from a supercell with a multiplicity of 4 or less. The phonon density of states was also computed for ThO2 and is shown in Supplementary Fig. 9.

Time-of-flight inelastic neutron scattering

The wide Angular Range Chopper Spectrometer (ARCS) at the Spallation Neutron Source of Oak Ridge National Laboratory39 was used to perform neutron scattering measurements presented in this work. Single crystal samples were aligned in the [HHL] plane and an incident neutron energy of 50, 120, or 140 meV was used. The resulting energy resolution (FWHM) at the elastic line was 1.56, 5.25, and 4.531 meV for Ei = 50, 120, 140 meV, respectively. At a given value of Ei, the energy resolution depends on the neutron energy transfer and improves at higher neutron energy loss. ARCS can use three interchangeable Fermi choppers, with only the ARCS-100-1.5 chopper used here, which is optimal for measurements with incoming energy near 100 meV and has 1.5 m curvature of the chopper blades, and was rotated at 600 Hz40. The 300 K and above temperatures were measured using a Nb holder in a MICAS furnace. The 5 K measurements used an Al sample holder and a closed-cycle refrigerator. The four-dimensional volumes of scattered intensity as a function of Q and E were analyzed using the HORACE41 and DAVE42 software packages.

Supplemental Information

Supplemental Information is available for this paper.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Wan, C. et al. Development of novel thermoelectric materials by reduction of lattice thermal conductivity. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 11, 044306 (2010).

Chernatynskiy, A. & Phillpot, S. R. Phonon-mediated thermal transport: confronting theory and microscopic simulation with experiment. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 17, 1–9 (2013).

Yang, J. et al. Acoustic-optical phonon up-conversion and hot-phonon bottleneck in lead-halide perovskites. Nat. Commun. 8, 14120 (2017).

Locatelli, G., Mancini, M. & Todeschini, N. Generation IV nuclear reactors: current status and future prospects. Energy Policy 61, 1503–1520 (2013).

Maradudin, A. & Fein, A. Scattering of neutrons by an anharmonic crystal. Phys. Rev. 128, 2589 (1962).

Kokkedee, J. J. Anharmonic effects in coherent scattering of neutrons by crystals - a formal treatment of shift and width of peaks in scattering spectrum. Physica 28, 374 (1962).

Cowley, R. Anharmonic crystals. Rep. Prog. Phys. 31, 123 (1968).

Fermi, E., Pasta, P., Ulam, S. & Tsingou, M. Studies of the nonlinear problems. Tech. Rep. https://doi.org/10.2172/4376203 (1955).

Berman, G. & Izrailev, F. The Fermi–Pasta–Ulam problem: fifty years of progress. Chaos 15, 015104 (2005).

Drazin, P. G. & Johnson, R. S. Solitons: An Introduction Vol. 2 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1989).

Sievers, A. & Takeno, S. Intrinsic localized modes in anharmonic crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 970 (1988).

Manley, M. E. et al. Intrinsic localized modes observed in the high-temperature vibrational spectrum of NaI. Phys. Rev. B 79, 134304 (2009).

Manley, M. E. et al. Intrinsic anharmonic localization in thermoelectric PbSe. Nat. Commun. 10, 1928 (2019).

Clausen, K. et al. Inelastic neutron scattering investigation of the lattice dynamics of ThO2 and CeO2. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 2: Mol. Chem. Phys. 83, 1109–1112 (1987).

Mann, M. et al. Hydrothermal growth and thermal property characterization of ThO2 single crystals. Cryst. Growth Des. 10, 2146–2151 (2010).

Szpunar, B. & Szpunar, J. A. Theoretical investigation of structural and thermo-mechanical properties of Thoria up to 3300 K temperature. Solid State Sci. 36, 35 (2014).

Kittel, C. Introduction to Solid State Physics Vol. 8 (Wiley, New York, 1976).

Rodine, E. T. & Land, P. L. Electronic defect structure of single-crystal ThO2 by thermoluminescence. Phys. Rev. B 4, 2701 (1971).

Squires, G. L. Introduction to the Theory of Thermal Neutron Scattering (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2012).

Rønnow, H., Regnault, L.-P. & Lorenzo, J. Chasing ghosts in reciprocal space-a novel inelastic neutron multiple scattering process. Physica B 350, 11–16 (2004).

Moon, R. & Shull, C. The effects of simultaneous reflections on single-crystal neutron diffraction intensities. Acta Crystallogr. 17, 805–812 (1964).

Toda, M. Theory of Nonlinear Lattices Vol. 20 (Springer Sci. & Bus. Media, 2012).

Pang, J. W. et al. Phonon lifetime investigation of anharmonicity and thermal conductivity of UO2 by neutron scattering and theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 157401 (2013).

Schmalzl, K., Strauch, D. & Schober, H. Lattice-dynamical and ground-state properties of CaF2 studied by inelastic neutron scattering and density-functional methods. Phys. Rev. B 68, 144301 (2003).

Yin, Q. & Savrasov, S. Y. Origin of low thermal conductivity in nuclear fuels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 225504 (2008).

Kim, H., Kim, M. H. & Kaviany, M. Lattice thermal conductivity of UO2 using ab-initio and classical molecular dynamics. J. Appl. Phys. 115, 123510 (2014).

Fu, L., Kornbluth, M., Cheng, Z. & Marianetti, C. A. Group theoretical approach to computing phonons and their interactions. Phys. Rev. B 100, 014303 (2019).

Birman, J. Theory of Crystal Space Groups and Lattice Dynamics: Infra-Red and Raman Optical Processes of Insulating Crystals (Springer, 1974).

Mertens, F. & Buttner, H. Dynamic correlations for the Toda lattice in the soliton-gas picture. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 15, 1831 (1982).

Diederich, S. Time-dependent correlations in the exponential lattice. II. Response functions of the monatomic lattice at low temperatures. Phys. Rev. B 24, 3193 (1981).

Diederich, S. Force-force correlations in the Toda chain. Phys. Lett. A 86, 294–296 (1981).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Atoms, molecules, solids, and surfaces: applications of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation. Phys. Rev. B 46, 6671 (1992).

Blochl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758 (1999).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Abinitio molecular-dynamics for liquid-metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab-initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Abernathy, D. L. et al. Design and operation of the wide angular-range chopper spectrometer arcs at the spallation neutron source. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 83, 015114 (2012).

Lin, J. Y., Banerjee, A., Islam, F., Le, M. D. & Abernathy, D. L. Energy dependence of the flux and elastic resolution for the arcs neutron spectrometer. Phys. B 562, 26–30 (2019).

Ewings, R. et al. Horace: software for the analysis of data from single crystal spectroscopy experiments at time-of-flight neutron instruments. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 834, 132–142 (2016).

Azuah, R. T. et al. Dave: a comprehensive software suite for the reduction, visualization, and analysis of low energy neutron spectroscopic data. J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 114, 341 (2009).

Acknowledgments

M.S.B., M.E.M., L.F., C.A.M., and J.M.M. were supported by the Center for Thermal Energy Transport under Irradiation, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, United States, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. Portions of this research used resources at the Spallation Neutron Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated by the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. This research used resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, a DOE Office of Science User Facility supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. C.A.M. acknowledges useful conversations with Zhengqian Cheng. We thank K. and S. Gofryk for providing the CaF2 crystal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.E.M. conceived of the neutron scattering experiment. M.S.B., D.L.A., and M.E.M. performed the neutron scattering measurements and analyzed the data. L.F. and C.A.M. performed the DFT calculations. K.R., D.T., T.A.P., and J.M.M. synthesized the sample and performed the sample characterization measurements. M.S.B., C.A.M., and M.E.M. wrote the paper, and all authors contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bryan, M.S., Fu, L., Rickert, K. et al. Nonlinear propagating modes beyond the phonons in fluorite-structured crystals. Commun Phys 3, 217 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-00483-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-00483-2

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.