Abstract

Neurofilament light chain (NfL) is a novel biomarker of neurodegenerative diseases. It is detectable in the peripheral blood, allowing low-invasive assessment of early signs of neurodegeneration. The level of NfL gradually increases with age; however, what other factors affect it remains unclear. The present study examined the association between blood NfL level and renal function among healthy participants undergoing a health check (n = 43, serum NfL) and patients with diabetes mellitus (n = 188, plasma NfL). All participants were 60 years of age or older; none were diagnosed with dementia. In each group, levels of blood NfL and serum creatinine significantly correlated (coefficient r = 0.50, 0.56). These associations remained statistically significant even after adjustment for age, sex, and body mass index. These findings indicate that blood NfL level might be partially affected by renal function. We recommend measuring renal function for a more precise evaluation of neuroaxonal damage, in particular, among older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An ability to detect and track the course of a neurodegenerative disease is paramount to research and clinical practice, allowing evidence-based decisions regarding treatment initiation and outcome evaluation. Neurofilament light chain (NfL) is a neuronal cytoskeletal protein primarily expressed in large-caliber myelinated axons1,2. It has recently gained attention as a biomarker of neuroaxonal damage. Ultrasensitive immunodetection methods enabled reliable quantification of NfL in not only cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) but also serum and plasma3. Previous studies have reported an association between CSF and blood concentrations of NfL, suggesting both reflects shared physiological and pathological mechanisms within the central nervous system (CNS)4,5,6,7. Blood-based measurement of NfL is a promising low-invasive method of assessing various neurologic conditions, including multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, frontotemporal dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, traumatic brain injury, and HIV-1 associated neurocognitive disorders5,8,9,10,11,12,13,14.

To effectively use NfL as a biomarker of neurodegeneration for research purposes, accurate identification of potentially confounding factors is required. A recent study has reported an association between plasma NfL level and body mass index (BMI) or blood volume15. However, the evidence is inconsistent on whether there is an association between blood NfL level and renal function16,17. Blood NfL and renal function both change with age, but to our knowledge, no study had investigated the association between plasma NfL level and renal function adjusted for age.

The present study investigated the relationship between blood NfL concentration and renal function in two groups separately and first assessed whether this relationship is independent of age, sex, and BMI.

Methods

Study participants

This study was approved by the research ethics committees of Osaka University Health and Counseling Center (HaCC), and Osaka University Hospital. All participants provided written informed consent, and all research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

In the Health-Checkup (HC) group, 158 study participants were employees of Osaka University (aged > 60 years) who received an annual medical exam between April 2016 and March 2017 at the HaCC. Individuals with HbA1c (hemoglobin A1c) > 6.5% were excluded from the analysis. Serum samples were collected, processed, aliquoted, and frozen for later use. Samples underwent the freeze–thaw procedure only once. We randomly selected 44 out of 158 samples for NfL measurement and analysis, based on sample size calculation described below.

In addition, we recruited 198 outpatients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) who visited the Department of Metabolic Medicine of Osaka University Hospital, Osaka, Japan, from July 2018 to June 2019. Clinical data or blood samples were not available for 12 individuals. Thus, a total of 188 participants were included in this study.

Measurements of serum creatinine and estimation of glomerular filtration rate

We examined the relationship between blood NfL and serum creatinine levels in the HC group, since serum creatinine level reflects renal function.

In both groups, serum creatinine and urea nitrogen levels were acquired from the existing medical records. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the following formula developed and validated in the Japanese population (1), which uses age and sex as surrogates for creatinine generation18:

Measurements of serum neurofilament light chain

Serum or plasma NfL concentration was measured in duplicate with ultrasensitive single-molecule array (Simoa) platform, using Simoa NF-Light Advantage kits on a Simoa HD-1 Analyzer instrument (Quanterix Corporation), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The lower limit of quantification for the NfL concentration was 0.466 pg/mL. Samples with either fatal measurement errors or coefficients of variance (CV) > 20% were excluded from the analysis. In all batches, two types of quality-control samples provided in the kit were measured in duplicate, ensuring measurement validity.

In the HC group, one sample was excluded due to fatal measurement errors in both replicates. The remaining 43 samples were all included in the analysis. The mean CV of duplicates in this group was 5.3%. In the DM group, all 188 samples were included in the analysis. The mean CV of duplicates in this group was 3.6%.

Statistical analysis

The sample size in the HC group was calculated by G*Power version 3.1.9.619, using the following parameters: r(correlation coefficient) = 0.4, α = 0.05, Power(1 − β) = 0.8, which intended to detect correlation with medium-to-large effect size.

Due to the non-normal distribution of the data, blood NfL and creatinine values were log-transformed before statistical calculations were performed (Fig. S3). The Pearson correlation was used to calculate the strength of the association between variables of interest. A Student’s t-test was used to compare blood NfL levels between sexes. Using blood NfL as a dependent variable, age, sex, BMI and serum creatinine were included in a linear regression analysis. Because age, sex, and serum creatinine are used for the eGFR calculation, multivariate adjustment by these variables was not performed when analyzing the association between eGFR and blood NfL level to avoid collinearity problems.

All tests were two-sided. Statistical significance was set as p < 0.05. JMP Pro version 14.3.0 (SAS Institute Inc.) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Participants’ demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. All participants were aged above 60 years.

Association between blood NfL and serum creatinine levels

The two groups were separately assessed for an association between blood NfL level and serum creatinine level.

Serum NfL was significantly correlated with serum creatinine levels in the HC group (r = 0.50, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.23, 0.69, p = 0.0007; Fig. 1a).

In the DM group, plasma NfL level significantly correlated with serum creatinine level (r = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.45, 0.65, p < 0.0001; Fig. 1b), consistent with the HC group findings.

Association with age, sex, and BMI

As associations between blood NfL level, age, and BMI have been previously reported5,10,15, we adjusted our regression analysis of the association between blood NfL and serum creatinine levels for age, sex, and BMI (Table 2).

In the HC group, serum NfL level was not significantly associated with age (p = 0.48) or BMI (p = 0.80). No significant differences in mean serum NfL levels were observed between sexes (p = 0.56). The association between serum NfL and serum creatinine levels remained significant after adjusting for age, sex, and BMI (p = 0.0004).

In the DM group, there was a significant correlation between plasma NfL level and age (r = 0.40, 95% CI: 0.28, 0.51, p < 0.0001), but not between serum creatinine level and age (r = 0.07, 95% CI: − 0.07, 0.21, p = 0.30). BMI was negatively correlated with plasma NfL level (r = − 0.23, 95% CI: − 0.36, − 0.09, p = 0.0014). No significant differences in mean plasma NfL levels were observed between sexes (p = 0.10). After adjusting for age, sex, and BMI, the association between plasma NfL and serum creatinine levels remained significant (p < 0.0001).

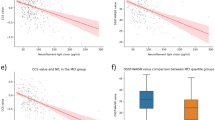

Estimated renal function and blood NfL level

A moderate correlation between blood NfL level and eGFR was observed in the HC (r = − 0.446, 95% CI: − 0.652, − 0.178, p = 0.0019) and DM group (r = − 0.473, 95% CI: − 0.578, − 0.355, p < 0.0001), indicating that approximately 20% of the variability in blood NfL levels can be explained by renal clearance (Fig. 2).

Discussion

This cross-sectional study of two different populations showed a positive correlation between blood NfL and serum creatinine levels in each group, indicating that blood NfL level may be partially influenced by renal function. Moreover, we have shown that blood NfL level in the DM group significantly correlated with age, but not with sex, a finding consistent with previous reports5,10,15, whereas the HC group analysis was underpowered to detect some of the association due to narrow age distribution and focused on detecting moderate-to-strong association. In the present study, the correlation between blood NfL and serum creatinine levels remained significant after adjustment for age, sex, and BMI. Estimated GFR calculated from serum creatinine, age, and sex was also significantly correlated with blood NfL in each group. These findings support the hypothesis about a negative correlation between blood NfL levels and renal function.

Two reports assessed relationships between blood NfL level and renal function. Consistent with the present data, Korley et al. have reported poor renal function as associated with a higher serum NfL level in a single cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes (mean age = 62.8 years)16. Concurrently, Hermansson et al. reported that plasma NfL level is not correlated with serum creatinine levels among patients with HIV infection (median age = 41 years)17. This inconsistency may be explained by between-study differences in age distribution, suggesting that the relationship between blood NfL and renal function becomes more evident among older adults. Not only in patients with type 2 diabetes, but the current study also showed that the association between blood NfL and renal function may be present in healthy individuals.

While the mechanism underlying how kidney function affects blood NfL dynamics are not known, there are some possibilities. One hypothesis is that blood NfL is cleared by the kidneys. This hypothesis suggests there is a risk of overestimating the extent of neuroaxonal damage among adults with low renal function.

Another possible mechanism incorporates the other functions of the kidneys. The decline of renal function leads to low levels of erythropoietin (EPO) and active vitamin D, both of which are primarily synthesized in the kidney20. EPO receptors are expressed in not only the bone marrow but also the brain21,22,23, and EPO is reported to have neuroprotective effects24. Active vitamin D is also reported to have neuroprotective effects25, and its deficiency is associated with various neuropsychological diseases such as depression, Alzheimer’s disease, and cerebrovascular dementia26,27,28,29. Blood levels of EPO and active vitamin D may link renal function and neuronal damage.

Although further investigations are required to determine the underlying mechanism, studies involving blood NfL level should assess renal function with serum creatinine or eGFR. When involving an older adult population, in particular, such an approach can help achieve precise assessment of neuroaxonal damage within the CNS.

This study has several limitations. Since we did not measure CSF NfL levels, it remains unknown whether NfL dynamics within the CNS are related to renal function. However, blood NfL level has been reported to strongly correlate with the CSF NfL level4,5,6,7. Because the study group comprised participants aged 60 years and older, these findings are not necessarily generalizable to all age groups. The sample size of the HC group was underpowered to detect a correlation coefficient smaller than 0.4 and the age distribution was narrow due to the Japanese system of mandatory retirement at the age of 65 while previous studies reported the correlation coefficient between age and blood NfL to be 0.32–0.5930,31,32. The association of blood NfL with renal function is confirmed in two distinct clinical groups, but the probability of confounding by comorbidities of diabetes such as peripheral neuropathy cannot be excluded, because we did not analyze the association with severities of comorbidities of diabetes in the DM group. Finally, because the present study used exclusively cross-sectional data, a causal relationship between blood NfL level and renal function was not assessed.

In summary, we observed a moderate correlation between blood NfL level and renal function among older adults who were healthy or had type 2 diabetes, which was independent of age, sex, and BMI. When analyzing blood NfL level as a marker of neurodegeneration, we recommend measuring renal function to assess the extent of neuroaxonal damage more precisely.

Data availability

The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Khalil, M. et al. Neurofilaments as biomarkers in neurological disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 14, 577–589 (2018).

Schlaepfer, W. & Lynch, R. Immunofluorescence studies of neurofilaments in the rat and human peripheral and central nervous system. J. Cell Biol. 74, 241–250 (1977).

Hansson, O. et al. Blood-based NfL: a biomarker for differential diagnosis of parkinsonian disorder. Neurology 88, 930–937 (2017).

Gaiottino, J. et al. Increased neurofilament light chain blood levels in neurodegenerative neurological diseases. PLoS ONE 8, e75091 (2013).

Disanto, G. et al. Serum neurofilament light: a biomarker of neuronal damage in multiple sclerosis: serum NfL as a Biomarker in MS. Ann. Neurol. 81, 857–870 (2017).

Benedet, A. L. et al. Plasma neurofilament light associates with Alzheimer’s disease metabolic decline in amyloid-positive individuals. Alzheimers Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 11, 679–689 (2019).

Novakova, L. et al. Monitoring disease activity in multiple sclerosis using serum neurofilament light protein. Neurology 89, 2230–2237 (2017).

Weydt, P. et al. Neurofilament levels as biomarkers in asymptomatic and symptomatic familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 79, 152–158 (2016).

Gisslén, M. et al. Plasma concentration of the neurofilament light protein (NFL) is a biomarker of CNS injury in HIV Infection: a cross-sectional study. EBioMedicine 3, 135–140 (2015).

Mattsson, N., Andreasson, U., Zetterberg, H. & Blennow, K. Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative. Association of plasma neurofilament light with neurodegeneration in patients with alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 74, 557–566 (2017).

Pijnenburg, Y. A. L., Verwey, N. A., van der Flier, W. M., Scheltens, P. & Teunissen, C. E. Discriminative and prognostic potential of cerebrospinal fluid phosphoTau/tau ratio and neurofilaments for frontotemporal dementia subtypes. Alzheimers Dement. Amst. Neth. 1, 505–512 (2015).

Shahim, P., Zetterberg, H., Tegner, Y. & Blennow, K. Serum neurofilament light as a biomarker for mild traumatic brain injury in contact sports. Neurology 88, 1788–1794 (2017).

Lu, C.-H. et al. Neurofilament light chain: a prognostic biomarker in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology 84, 2247–2257 (2015).

Feneberg, E. et al. Multicenter evaluation of neurofilaments in early symptom onset amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology 90, e22–e30 (2018).

Manouchehrinia, A. et al. Confounding effect of blood volume and body mass index on blood neurofilament light chain levels. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 7, 139–143 (2020).

Korley, F. K. et al. Serum NfL (Neurofilament Light Chain) levels and incident stroke in adults with diabetes mellitus. Stroke 50, 1669–1675 (2019).

Hermansson, L. et al. Plasma concentration of neurofilament light chain protein decreases after switching from tenofovir disoproxil fumarate to tenofovir alafenamide fumarate. PLoS ONE 14, e0226276 (2019).

Matsuo, S. et al. Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. . Am. J. Kidney Dis. Off. J. Natl. Kidney Found. 53, 982–992 (2009).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A. & Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 41, 1149–1160 (2009).

Webster, A. C., Nagler, E. V., Morton, R. L. & Masson, P. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet Lond. Engl. 389, 1238–1252 (2017).

Marti, H. H. et al. Erythropoietin gene expression in human, monkey and murine brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 8, 666–676 (1996).

Juul, S. E., Anderson, D. K., Li, Y. & Christensen, R. D. Erythropoietin and erythropoietin receptor in the developing human central nervous system. Pediatr. Res. 43, 40–49 (1998).

Juul, S. E., Yachnis, A. T., Rojiani, A. M. & Christensen, R. D. Immunohistochemical localization of erythropoietin and its receptor in the developing human brain. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. Off. J. Soc. Pediatr. Pathol. Paediatr. Pathol. Soc. 2, 148–158 (1999).

Simon, F., Floros, N., Ibing, W., Schelzig, H. & Knapsis, A. Neurotherapeutic potential of erythropoietin after ischemic injury of the central nervous system. Neural Regen. Res. 14, 1309–1312 (2019).

Fernandes de Abreu, D. A., Eyles, D. & Féron, F. Vitamin D, a neuro-immunomodulator: implications for neurodegenerative and autoimmune diseases. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34(Suppl 1), S265–S277 (2009).

Ganji, V., Milone, C., Cody, M. M., McCarty, F. & Wang, Y. T. Serum vitamin D concentrations are related to depression in young adult US population: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Int. Arch. Med. 3, 29 (2010).

Dursun, E., Gezen-Ak, D. & Yilmazer, S. A novel perspective for Alzheimer’s disease: vitamin D receptor suppression by amyloid-β and preventing the amyloid-β induced alterations by vitamin D in cortical neurons. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD 23, 207–219 (2011).

Buell, J. S. et al. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, dementia, and cerebrovascular pathology in elders receiving home services. Neurology 74, 18–26 (2010).

Farid, K. et al. Correlation between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and regional cerebral blood flow in degenerative dementia. Nucl. Med. Commun. 33, 1048–1052 (2012).

Hviid, C. V. B., Knudsen, C. S. & Parkner, T. Reference interval and preanalytical properties of serum neurofilament light chain in Scandinavian adults. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365513.2020.1730434 (2020).

Hu, H. et al. Neurofilament light chain plasma concentration predicts neurodegeneration and clinical progression in nondemented elderly adults. Aging 11, 6904–6914 (2019).

Mielke, M. M. et al. Plasma and CSF neurofilament light: Relation to longitudinal neuroimaging and cognitive measures. Neurology 93, e252–e260 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants who took part in this study. We thank all medical staff that collected samples and data used in this study. We thank Yukiko Mizutani for the technical assistance in stable NfL measurement. This study was supported in part by grants from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (JP19dk0207039 to M.I. and JP19dk0207042 to T.K.). S.A. is supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (19K23943). S.G. and K.M. are supported by the JSPS KAKENHI (JP17H05091, JP18K19515), AMED (JP18ek0109316), SENSHIN Medical Research Foundation (to K.M. and Dr. Shinji Tagami), Takeda Science Foundation and Mochida Memorial Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in sample and data collection. S.A. and N.M. measured blood NfL concentration. S.A., N.M., and D.K. performed statistical analyses. S.A., N.M., D.K., and T.K. designed the study and wrote the manuscript with the help of the coauthors S.G., R.M., K.Y., Y.S., K.M., H.A., J.K., N.M., O.M., T.M., H.I., I.S., and M.I. M.I. and T.K. obtained funding for the present study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akamine, S., Marutani, N., Kanayama, D. et al. Renal function is associated with blood neurofilament light chain level in older adults. Sci Rep 10, 20350 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76990-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76990-7

This article is cited by

-

Correlation analysis between smoke exposure and serum neurofilament light chain in adults: a cross-sectional study

BMC Public Health (2024)

-

The impact of kidney function on plasma neurofilament light and phospho-tau 181 in a community-based cohort: the Shanghai Aging Study

Alzheimer's Research & Therapy (2024)

-

Neurofilaments as biomarkers in neurological disorders — towards clinical application

Nature Reviews Neurology (2024)

-

Identification and management of subclinical disease activity in early multiple sclerosis: a review

Journal of Neurology (2024)

-

Serum neurofilament light chain in COVID-19 and the influence of renal function

European Journal of Medical Research (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.