Abstract

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a strong infectious pathogen that may cause severe respiratory infections. Since this pathogen may possess a latent period after infection, which sometimes leads to misdiagnosis by traditional diagnosis methods, the establishment of a rapid and sensitive diagnostic method is crucial for transmission prevention and timely treatment. Herein, a novel detection method was established for M. pneumoniae detection. The method, which improves upon a denaturation bubble-mediated strand exchange amplification (SEA) that we developed in 2016, is called accelerated SEA (ASEA). The established ASEA achieved detection of 1% M. pneumoniae genomic DNA in a DNA mixture from multiple pathogens, and the limit of detection (LOD) of ASEA was as low as 1.0 × 10−17 M (approximately 6.0 × 103 copies/mL). Considering that the threshold of an asymptomatic carriage is normally recommended as 1.0 × 104 copies/mL, this method was able to satisfy the requirement for practical diagnosis of M. pneumoniae. Moreover, the detection process was finished within 20.4 min, significantly shorter than real-time PCR and SEA. Furthermore, ASEA exhibited excellent performance in clinical specimen analysis, with sensitivity and specificity of 96.2% and 100%, respectively, compared with the “gold standard” real-time PCR. More importantly, similar to real-time PCR, ASEA requires only one pair of primers and ordinary commercial polymerase, and can be carried out using a conventional fluorescence real-time PCR instrument, which makes this method low-cost and easy to accomplish. Therefore, ASEA has the potential for wide use in the rapid detection of M. pneumoniae or other pathogens in large numbers of specimens.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pneumonia, a common respiratory infectious disease with widespread global prevalence, is one of the major disease states resulting in mortality in children younger than 5 years [1, 2]. This disease is triggered by a variety of pathogens, including Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae and some types of coronavirus [3,4,5,6], among which M. pneumoniae is the cause of approximately 10–30% of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), especially in children and adolescents [7]. Besides the typical symptoms of pneumonia such as headache, sore throat, fever and cough, the infection of M. pneumoniae can also lead to multiple complications, including nervous system disorders, diarrhea, hemolytic anemia and myocarditis [8, 9]. However, these clinical symptoms are similar to those of respiratory diseases induced by other bacterial or viral infections, which thus might lead to misdiagnosis and delayed treatment [10]. Moreover, the incubation period of M. pneumoniae is roughly 2–4 weeks [11], and therefore most patients are unaware of the invasion of this pathogen for 14 days after infection, which greatly increases the risk of pathogen transmission in crowded places, such as schools. This is also one of the reasons why M. pneumoniae has caused frequent CAP outbreaks in school-aged children aged 5 to 15 years [8]. For these reasons, rapid and sensitive detection methods capable of accurately diagnosing M. pneumoniae early in the incubation period are critical in preventing the outbreak of M. pneumoniae-caused CAP.

Traditional diagnostic methods for M. pneumoniae include isolation culture and serological test, which are still generally used in medical institutions [12]. However, isolation culture is time-consuming, space-occupying and laborious, and usually takes several days to even more than 1 week to obtain detectable strains [13], since the antibodies can barely be detected in serum during the incubation period [14]. Besides, poor specificity has been reported for serological testing [15]. Therefore, these two traditional methods cannot meet the requirement for accurate, rapid and early diagnosis. Compared with the traditional methods, nucleic acid amplification technologies are normally free of the pathogen culture process and able to detect pathogens during the incubation period, exhibiting excellent specificity and sensitivity [16, 17]. Thus, these technologies are more desirable for early diagnosis, among which real-time polymerase chain reaction (real-time PCR) is the most widely used in clinical diagnosis [18, 19]. However, the amplification progress of conventional real-time PCR usually takes 1–1.5 h [20], which makes it difficult for the technology to meet the demands of situation requiring quick testing of a large number of samples, such as 2019-nCoV detection in airports or seaports. Although some extreme PCR methods greatly shorten the detection time to less than 100 s, even to 46 s according to some reports, these efficient approaches are dependent on special DNA polymerase and sophisticated instruments, and generally require more than a tenfold series of primers and polymerase, all of which make the process costly and restrict the widespread application of this technology [21, 22]. In our previous work, we developed an isothermal denaturation bubble-mediated strand exchange amplification (SEA) method, which is started by the invasion of one pair of primers into the denaturation bubbles randomly formed in a DNA duplex triggered by DNA respiration [23]. This isothermal reaction relies on Bst 2.0 WarmStart DNA, an easily available commercial enzyme with polymerase and strand displacement activity which allows the primers to be extended at a constant reaction temperature [10, 24,25,26]. Although SEA takes less time than conventional real-time PCR to detect pathogens, including M. pneumoniae, the time required for this method is only approximately 25% shorter than real-time PCR, and its sensitivity is obviously lower, though this isothermal amplification method requires no sophisticated temperature control equipment [27]. We recently discovered that the amplification efficiency of SEA could be significantly improved by introducing a narrow range of rapid thermal cycling [28], which does not require special equipment and can be performed by conventional fluorescence real-time PCR instruments. Also, similar to SEA, this accelerated SEA (ASEA) is initiated by Bst 2.0 WarmStart DNA polymerase and one pair of primers, rather than expensive special polymerase. Therefore, this method possesses the potential to fulfill the requirements for fast and low-cost detection of epidemic pathogens from a large number of specimens.

Due to the advantages described above, herein, the ASEA method was established for M. pneumoniae detection for the first time. Specifically, we first optimized reaction conditions, followed by feasibility, specificity, sensitivity and anti-jamming capacity assessment. Finally, ASEA was employed for M. pneumoniae nucleic acid testing of clinical specimens to verify the accuracy of this novel method by comparison with real-time PCR, the current “gold standard.” The objective was to provide a rapid, low-cost and sensitive detection method with conventional instruments and easily available commercial polymerase for early diagnosis of M. pneumoniae and other epidemic pathogens.

Materials and methods

Materials and reagents

Fifty sputum specimens from patients with respiratory tract infection symptoms were provided by the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. All of the sputum specimens were immediately stored at −20 °C after collection for subsequent use. M. pneumoniae (ATCC 15531) and nine other reference pathogen strains that may also infect humans and cause pneumonia with similar symptoms, including Streptococcus pneumoniae (ATCC BAA-255), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA, ATCC 43300), Escherichia coli (ATCC 43895), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 47085), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (ATCC 27294), Legionella pneumophila (ATCC 33823), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (ATCC 17666), Haemophilus influenzae (ATCC 49247) and Acinetobacter baumannii (ATCC 19606), were provided by Navid Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Qingdao China). Genomic DNA of sputum specimens was extracted using a High Pure Viral Nucleic Acid extraction kit purchased from Roche Applied Science (Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. dNTP was purchased from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). EvaGreen was purchased from Bridgen (Beijing, China). Bst 2.0 WarmStart DNA polymerase and ISO buffer were purchased from New England Biolabs Inc. (Beijing, China). The 20-bp DNA ladder was purchased from Takara Co., Ltd. (Dalian, China).

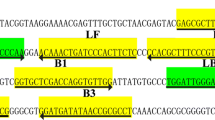

ASEA primers specific to M. pneumoniae 16S rDNA were designed and optimized by NCBI primer-BLAST (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast), NUPACK software (http://www.nupack.org/) and the DINAMelt web server (http://unafold.rna.albany.edu/?q=DINAMelt), and were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) and purified by HPLC. All other reagents and buffers used in this study were of analytical grade.

ASEA reaction

The ASEA reaction was performed in 20 μL amplification mixture containing 2 μL of the relevant templates, 3.0 × 10−6 M primers F and R, 2 μL ISO buffer, 0.5 μL EvaGreen, 0.2 μL Bst 2.0 WarmStart DNA polymerase and 1.6 μL dNTPs. The amplification mixture was subjected to rapid thermal cycles between a first temperature (T1) and a second temperature (T2) using the CFX Connect™ Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad, CA, USA). In particular, each thermal cycle consisted of incubating the amplification mixture at T1 for 1 s, then immediately reducing the reaction temperature to T2 at a rate of 3 °C/s, and incubating the amplification mixture at T2 for another 1 s, before immediately increasing the temperature back to T1 at a rate of 5 °C/s. The fluorescence signal emitted from the amplification mixture was scanned every thermal cycle and plotted over time to monitor the amplification in real time. Reaction temperatures including T1 and T2 were optimized prior to using this method for sputum specimen detection. Specifically, two series of temperatures from 76 °C to 72 °C and from 61 °C to 57 °C were selected as T1 and T2, respectively. T1 and T2 at which the reaction showed the lowest threshold time (Tt) and highest specificity were employed for sputum sample detection.

Specificity, sensitivity and anti-jamming capability of ASEA

Genomic DNA extracts of the M. pneumoniae strain and the nine pathogens mentioned above were used as template for ASEA to assess the feasibility of this method for detecting M. pneumoniae and distinguishing this pathogen from others. The sensitivity of ASEA was evaluated by employing tenfold serial dilution of M. pneumoniae genomic DNA ranging from 1.0 × 10−11 M to 1.0 × 10−18 M as the templates. Additionally, a series of multicomponent blends containing 0%, 1%, 5%, 10%, 50% and 100% of M. pneumoniae genomic DNA were prepared by mixing genomic DNA extracts of the abovementioned pathogens. These mixtures, which possessed the same final DNA weight of 200 ng, were subsequently utilized for anti-jamming assay of ASEA, and the amplification products were subsequently loaded on 4% agarose gel and subjected to electrophoresis for 0.5 h at 110 V. Each assay was conducted in triplicate.

Detection of M. pneumoniae in sputum samples

The feasibility of ASEA in actual samples was validated by detecting M. pneumoniae in the genomic DNA extracts of sputum specimens collected from patients with the symptoms of respiratory infection. Prior to the detection, all of the above sputum specimens were tested by gold-standard real-time PCR. The sensitivity and specificity of ASEA were assessed by comparing the number of negative and positive detections, respectively, with the real-time PCR results.

Results and discussion

Design of ASEA for M. pneumoniae detection

The mechanism of ASEA is shown in Fig. 1. The initial cycling of ASEA is similar to SEA, which is also initiated by the invasion of the primers into the denaturation bubbles and extended with the help of Bst 2.0 WarmStart DNA polymerase. As the amplification reaction progresses, the short amplicons, which can melt to ssDNA at T1 of the thermal cycling and bind with primers at T2, largely accumulate. Therefore, the later cycling is triggered by both melting and annealing of amplicons, as well as the invasion of primers into denaturation bubbles. Based on the primer design strategy we established previously [29], a pair of primers specific to M. pneumoniae 16S rDNA was designed with amplicon length of 36 bp (Table 1), while M. pneumoniae genomic DNA at a concentration of 1.0 × 10−11 M was applied as template. Subsequently, in order to achieve the melting of the short amplicons and binding of primers with targets during the thermal cycling, a series of temperatures was set as T1 (76 °C, 75 °C, 74 °C, 73 °C and 72 °C) and T2 (61 °C, 60 °C, 59 °C, 58 °C and 57 °C) for reaction temperature optimization based on the melting temperature (Tm) value of amplicon and primers, respectively. According to our previous work on SEA, a reaction temperature slightly lower than the average value of the primers’ Tm value is the most beneficial for the combination of primers to target; therefore, 60 °C was first fixed as T2 for T1 optimization. As shown in Fig. 2a, the reaction with T1 of 74 °C exhibited the lowest Tt value, suggesting this temperature was best for this amplification reaction. It was observed that even a small number of amplification products were detected in the reaction with 76 °C as T1, which may be attributed to the fact that the polymerase was inactivated during the rapid thermal cycling ranging from 76 °C to 58 °C. We then fixed 74 °C as T2 for T1 optimization, the result of which is shown in Fig. 2b. To our surprise, the reaction with T2 of 58 °C instead of 60 °C exhibited the lowest Tt value. Finally, to confirm that 74 °C was still the optimal T1 when 58 °C was employed as T2, we fixed 58 °C as T2 to optimize T1 again. As expected, the reaction with 74 °C as T1 still showed the lowest Tt value (Fig. 2c). In summary, thermal cycling in the range of 74 °C to 58 °C was most beneficial for this ASEA reaction; thus, 74 °C and 58 °C were employed as T1 and T2, respectively, for subsequent research in this work. It was found that T1 and T2 were both slightly lower than the amplicon’s Tm value and average Tm value of primers, respectively. On one hand, a temperature lower than the primers’ Tm value ensured the strong binding of primers to the target sequence [30, 31], which was crucial for the subsequent amplification. On the other hand, the polymerase applied in this work displayed the best reaction performance at 60–72 °C, and would be inactivated within 20 min at 80 °C; thus a reaction temperature far beyond this range is not conducive to amplification reaction. Besides, an excessive temperature difference between T1 and T2 would also increase the time consumption of the temperature change process, thus extending the total reaction time. Therefore, a temperature higher than the amplicon’s Tm value in this research was not favorable for amplification, though denatured bubbles appeared in the DNA duplex more frequently at the target portion at a temperature higher than the amplicon’s Tm value, which would increase the probability of primers invading denatured bubbles [26]. Combining the above factors, thermal cycling between 58 °C and 74 °C was most beneficial for the ASEA reaction utilized in this work.

Schematic illustration of M. pneumoniae detection by ASEA. The initial cycling was mediated mainly by the invasion of primers into denaturation bubbles formed between the duplex of M. pneumoniae genomic DNA, whereas the later cycling was triggered by both melting of amplicons and invasion of primers into denaturation bubbles

T1 and T2 optimization of the ASEA method for detecting M. pneumoniae. (a) T1 optimization at the T2 value of 61 °C. ASEA reactions were carried out at T1 values of (1) 76 °C, (2) 75 °C, (3) 74 °C, (4) 73 °C and (5) 72 °C. 1′–5′ represent the corresponding NTC. (b) T2 optimization at the T1 value of 74 °C. ASEA reactions were carried out at T2 values of (1) 61 °C, (2) 60 °C, (3) 59 °C, (4) 58 °C and (5) 57 °C. 1′–5′ represent the corresponding NTC. (c) T1 optimization at the T2 value of 58 °C. ASEA reactions were carried out at T1 values of (1) 76 °C, (2) 75 °C, (3) 74 °C, (4) 73 °C and (5) 72 °C. 1′–5′ represent the corresponding NTC

The italic portion is the same with primer F. The sequence complementary to primer R is shown in bold.

Evaluation of ASEA for M. pneumoniae detection

The feasibility and specificity of ASEA were evaluated by performing amplification using genomic DNA of M. pneumoniae and nine other species of common pathogens mentioned above as templates, all at concentrations of 1.0 × 10−13 M (approximately 1.1 ng). As shown in Fig. 3a, significant fluorescence signal accumulation was observed only in the reactions with genomic DNA of M. pneumoniae as template, while hardly any fluorescence signal accumulation was detected in the reactions with other templates, which exhibited no obvious differences with NTC. This result demonstrated that ASEA was able not only to accomplish the amplification of the target sequence of M. pneumoniae, but also to avoid non-specific amplification and to distinguish M. pneumoniae from other common pathogens, suggesting the feasibility and good specificity of this method for M. pneumoniae detection.

(a) Feasibility and specificity of ASEA for M. pneumoniae detection with genomic DNA of M. pneumoniae and nine other common pathogens as template. 1 represents genomic DNA of M. pneumoniae, and 2–10 represent genomic DNA of S. pneumoniae, MRSA, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, M. tuberculosis, L. pneumophila, S. maltophilia, H. influenzae and A. baumannii, respectively. (b) Anti-jamming capability of ASEA for M. pneumoniae detection and (c) agarose gel electrophoresis image of corresponding ASEA products. 1 represents genomic DNA extract of M. pneumoniae, and 2–6 represent a mixture of the genomic DNA of the above pathogens with 50%, 10%, 5%, 1% and 0% genomic DNA of M. pneumoniae, respectively. The white dashed line frames the bands of 36-bp amplicons. M and NTC represent a 20-bp DNA ladder and no target control, respectively

With respect to practical detection application, M. pneumoniae is normally coexistent with multiple pathogens in the samples collected from patients. In order to assess the capability of detecting M. pneumoniae from the specimens comprising multiple pathogens, DNA mixtures with ratios of 50%, 10%, 5% and 1% M. pneumoniae genomic DNA prepared by blending genomic DNA extracts of the above pathogens were utilized as templates to carry out ASEA reactions with M. pneumoniae 16S rDNA-specific primers. M. pneumoniae genomic DNA extracts and a mixture of the other nine pathogen genomic DNA extracts were also employed as positive and negative control. The total amount of DNA in all the above mixtures was 200 ng to eliminate the influence of DNA content on amplification efficiency. As expected, the result showed that the fluorescence signals were obviously enhanced in genomic DNA extracts of M. pneumoniae in the mixtures containing 50%, 10%, 5% and 1% M. pneumoniae genomic DNA, with Tt values of 7.34 ± 0.09, 8.52 ± 0.15, 9.78 ± 0.24, 11.35 ± 0.08, and 12.04 ± 0.11 min, respectively. Low fluorescence signals were detected in the mixtures without M. pneumoniae genomic DNA and NTC (Fig. 3b), demonstrating that M. pneumoniae genomic DNA even as low as 1% could be accurately detected. Additionally, agarose gel electrophoresis was carried out, the result of which was consistent with that shown by fluorescence curves. The bands of 36-bp amplicons framed by the white dashed line were observed in the lane of the mixture containing M. pneumoniae genomic DNA, while hardly anything was detected in the lane with the mixture of genomic DNA from the other nine pathogens as well as NTC (Fig. 3c). The above results suggest that ASEA possesses high specificity and strong anti-jamming capability in DNA mixtures of multiple species. Moreover, since the Tt value exhibited significant correlations with the target DNA content in the mixtures, this method also showed great potential for the quantitative analysis of M. pneumoniae. Therefore, ASEA is feasible for the detection and analysis of M. pneumoniae in actual specimens collected from patients.

Sensitivity of ASEA for M. pneumoniae detection

According to a previous report, asymptomatic carriers of M. pneumoniae are common, especially among children [32], and the pathogens that they carry are still infectious and may cause widespread transmission, despite the absence of symptoms in these healthy carriers. Since the amount of M. pneumoniae in an asymptomatic carrier is normally at a lower level than that in patients, the establishment of sensitive diagnostic approaches that can distinguish asymptomatic carriers from uninfected individuals is critical for M. pneumoniae transmission prophylaxis. To verify the sensitivity of the ASEA method, a tenfold serial dilution of M. pneumoniae genomic DNA ranging from 1.0 × 10−11 M to 1.0 × 10−18 M was employed as the templates for ASEA reaction, and the results are shown in Fig. 4a. The fluorescence signal increased significantly in the reactions with the DNA template ranging from 1.0 × 10−11 M to 1.0 × 10−17 M, with Tt values of 8.14 ± 0.08, 10.34 ± 0.07, 12.13 ± 0.10, 14.11 ± 0.18, 16.02 ± 0.36, 17.82 ± 0.25 and 20.39 ± 0.16 min, respectively. In contrast, similar to the NTC, no obvious signal changes were observed in the reaction with the template concentration of 1.0 × 10−18 M, suggesting that ASEA could detect a concentration as low as 1.0 × 10−17 M of M. pneumoniae genomic DNA (1.2 × 102 copies in our 20-μl reaction system) within 20.4 min. Moreover, the Tt value exhibited a significant linear relationship with the negative logarithm (lg) of genomic DNA amount from 1.0 × 10−11 M to 1.0 × 10−17 M, with a correlation equation of Tt = −14.977 + 2.094 × (–lgCDNA) and a corresponding correlation coefficient (R2) of 0.9998, demonstrating the excellent stability of this method for M. pneumoniae detection in this concentration range (Fig. 4b). Compared with the SEA method we established previously, the detection limit and corresponding processing time were 1.0 × 10−14 M and approximately 60 min (only 14.1 min was required by ASEA to detect M. pneumoniae at this concentration), respectively. Therefore, this new method displayed a lower limit of detection (LOD) in obviously shorter time. In addition, while real-time PCR and loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) were reported as having lower LOD, reaching 2.2 × 103 copies/mL and 1.1 × 103 copies/mL (equivalent to 3.7 × 10−18 M and 1.8 × 10−18 M), respectively [33, 34], ASEA exhibited an equal advantage with regard to detection time in comparison with 1 h–1.5 h for conventional real-time PCR, while LAMP had a high rate of false-positive amplification according to some reports [35]. More importantly, ASEA can be operated using common real-time PCR devices and is free of complicated primer design processes and expensive special polymerase or instruments that are required for LAMP, digital PCR or extremely rapid PCR [21, 36,37,38]. Furthermore, since 1.0 × 104 copies/mL (equivalent to 1.7 × 10−17 M) genomic DNA is generally recommended as the threshold for distinguishing clinical infection of M. pneumoniae from asymptomatic carriage [39, 40], this rapid and sensitive method, whose LOD was lower than this threshold, possesses the potential for diagnosis of M. pneumoniae infection from an asymptomatic carriage in practical application. To sum up, the abovementioned advantages render ASEA a promising approach for rapid, accurate and low-cost diagnosis of M. pneumoniae infection.

Sensitivity of ASEA for M. pneumoniae detection. (a) The fluorescence curves of ASEA reactions with the template of M. pneumoniae genomic DNA at concentrations of (1) 1.0 × 10−11 M, (2) 1.0 × 10−12 M, (3) 1.0 × 10−13 M, (4) 1.0 × 10−14 M, (5) 1.0 × 10−15 M, (6) 1.0 × 10−16 M, (7) 1.0 × 10−17 M and (8) 1.0 × 10−18 M. (b) Linear relationship between the threshold time and the negative logarithmic values of the concentration of M. pneumoniae genomic DNA (−lgCDNA). Error bars represent the standard deviations of three independent measurements

Application of ASEA for diagnosis of M. pneumoniae infection in clinical specimens

A total of 50 specimens from patients with symptoms of respiratory tract infection, which had been assayed via the gold-standard real-time PCR by the hospital that provided these specimens in advance, were collected for verification of the potential application of ASEA in clinical diagnosis. As shown in Table 2, 26 of the 50 specimens were detected as positive by real-time PCR, while 25 of these positive specimens were also successfully diagnosed by ASEA, indicating that ASEA yielded a positive detection rate of 96.15% taking PCR as a reference, which was higher than SEA and LAMP, whose positive detection rates were 90.5% and 95.23%, respectively, according to our previous work [10]. The false-negative result of ASEA demonstrated that the sensitivity of ASEA was slightly lower than real-time PCR. However, from another perspective, the possibility of real-time PCR giving false detection results cannot be excluded. In contrast to the positive specimens, ASEA exhibited diagnostic results identical to those with real-time PCR for all remaining 24 specimens, which were diagnosed with the negative results by this gold standard, thus indicating that no false-positive diagnostic results appeared in the ASEA assay. That is, ASEA achieved specificity of 100.0%, higher than the 98.91% of LAMP. Although ASEA failed to exhibit 100.0% sensitivity based on the premise that real-time PCR would not give false results, this method still showed 100% specificity and had a favorable performance for M. pneumoniae detection in clinical specimens. Moreover, the slight differences between diagnostic results of these two methods are not statistically significant according to the result of chi-square tests (p > 0.05). In addition to excellent specificity and sensitivity, the running time of ASEA was only approximately 30 min, significantly shorter than real-time PCR, SEA and LAMP, whose processing took around 80 min, 60 min and 70 min, respectively. Furthermore, each testing of ASEA was estimated to cost approximately $0.24, which was close to SEA, including $0.05 for the reaction tube and pipette tip, and $0.19 for reagents, lower than PCR and LAMP, since Taq polymerase is normally more expensive than Bst 2.0 WarmStart DNA polymerase, while LAMP requires multiple pairs of primers. Hence, this rapid and low-cost method still presents great advantages in terms of efficiency, making ASEA more suitable for the situations that require fast detection of a large number of specimens, such as epidemic outbreaks or inspection and quarantine of airports and seaports.

Conclusion

In this present work, the ASEA method was successfully established for M. pneumoniae detection by introducing a narrow range of a rapid thermal cycling process in the SEA method that we developed previously. The range of the thermal cycling should be between the temperature slightly lower than the amplicon’s Tm value and that slightly lower than the average Tm value of primers to ensure high polymerase possessing activity and strong binding of primers to the target sequence. This method was able not only to accurately distinguish genomic DNA extracts of M. pneumoniae from other common pathogens, but also to detect 1% M. pneumoniae genomic DNA in a multi-DNA mixture. Moreover, the diagnosis time was shortened dramatically by this method, which detected 1.0 × 10−17 M of M. pneumoniae genomic DNA in 20.4 min via conventional amplification instruments and ordinary commercial polymerase. Since the LOD of ASEA was lower than the asymptomatic carriage threshold and its diagnostic time was much shorter than commonly used real-time PCR, we believe this rapid, low-cost, sensitive and highly specific method possesses great application potential for the rapid diagnosis of M. pneumoniae and other pathogens, as well as the development of relevant kits.

Availability of data and material

The authors declare that all data and materials support our published claims and comply with field standards.

Abbreviations

- 2019-nCoV:

-

2019 Novel coronavirus

- ASEA:

-

Accelerated strand exchange amplification

- CAP:

-

Community-acquired pneumonia

- LOD:

-

Limit of detection

- NTC:

-

No template control

- SEA:

-

Strand exchange amplification

- T1 :

-

First temperature

- T2 :

-

Second temperature

- Tm :

-

Melting temperature

- Tt :

-

Threshold time

References

Mina MJ, Klugman KP. The role of influenza in the severity and transmission of respiratory bacterial disease. Lancet Resp Med. 2014;2(9):750–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70131-6.

Walker CLF, Rudan I, Liu L, Nair H, Theodoratou E, Bhutta ZA, et al. Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet. 2013;381(9875):1405–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60222-6.

Waites KB, Xiao L, Liu Y, Balish MF, Atkinson TP. Mycoplasma pneumoniae from the respiratory tract and beyond. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30(3):747–809. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00114-16.

Dumke R, Schnee C, Pletz MW, Rupp J, Jacobs E, Sachse K, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia spp. infection in community-acquired pneumonia, Germany, 2011-2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(3):426–34. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2103.140927.

Cash P, Argo E, Ford L, Lawrie L, Mckenzie H. A proteomic analysis of erythromycin resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Electrophoresis. 2015;20(11):2259–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19990801)20:11<2259::AID-ELPS2259>3.0.CO;2-F.

Munster VJ, De Wit E, Feldmann H. Pneumonia from Human Coronavirus in a Macaque Model. New Engl J Med. 2013;368(16):1560–2. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1215691.

Atkinson TP, Balish MF, Waites KB. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, pathogenesis and laboratory detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32(6):956–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00129.x.

Yiş U, Kurul SH, Çakmakçı H, Dirik E. Mycoplasma pneumoniae: nervous system complications in childhood and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167(9):973–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-008-0714-1.

Wang K, Gill P, Perera R, Thomson A, Harnden A. Clinical symptoms and signs for the diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in children and adolescents with community-acquired pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10(10):D9175. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009175.pub2.

Shi W, Wei M, Wang Q, Wang H, Ma C, Shi C. Rapid diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumonia infection by denaturation bubble-mediated strand exchange amplification: comparison with LAMP and real-time PCR. Sci Rep-UK. 2019;9(1):896. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-36751-z.

Principi N, Esposito S. Emerging role of Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae in paediatric respiratory-tract infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2001;1(5):334–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00147-5.

Kawakami N, Namkoong H, Ohata T, Sakaguchi S, Saito F, Yuki H. Clinical features of Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018;18(5):814–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13278.

Barreda-García S, Miranda-Castro R, De-los-Santos-Álvarez N, Miranda-Ordieres AJ, Lobo-Castañón MJ. Helicase-dependent isothermal amplification: a novel tool in the development of molecular-based analytical systems for rapid pathogen detection. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2018;410(3):679–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-017-0620-3.

Al-Toma A, Volta U, Auricchio R, Castillejo G, Sanders DS, Cellier C, et al. European Society for the Study of Coeliac Disease (ESsCD) guideline for coeliac disease and other gluten-related disorders. United Eur Gastroent. 2019;7(5):583–613. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050640619844125.

Singh S, Singh J, Kumar S, Gopinath K, Mani K. Poor Performance of Serological Tests in the Diagnosis of Pulmonary Tuberculosis: Evidence from a Contact Tracing Field Study. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40213. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0040213.

Mothershed EA, Whitney AM. Nucleic acid-based methods for the detection of bacterial pathogens: Present and future considerations for the clinical laboratory. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;363(1–2):206–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cccn.2005.05.050.

Yang H, Chen Z, Cao X, Li Z, Stavrakis S, Choo J, et al. A sample-in-digital-answer-out system for rapid detection and quantitation of infectious pathogens in bodily fluids. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2018;410(27):7019–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-018-1335-9.

Wolff BJ, Thacker WL, Schwartz SB, Winchell JM. Detection of Macrolide Resistance in Mycoplasma pneumoniae by Real-Time PCR and High-Resolution Melt Analysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(10):3542–9. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00582-08.

Muniandy S, Dinshaw IJ, Teh SJ, Lai CW, Ibrahim F, Thong KL, et al. Graphene-based label-free electrochemical aptasensor for rapid and sensitive detection of foodborne pathogen. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2017;409(29):6893–905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-017-0654-6.

Zhao F, Liu L, Tao X, He L, Meng F, Zhang J. Culture-Independent Detection and Genotyping of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in Clinical Specimens from Beijing, China. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e141702. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141702.

Farrar JS, Wittwer CT. Extreme PCR: Efficient and Specific DNA Amplification in 15–60 Seconds. Clin Chem. 2015;61(1):145–53. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2014.228304.

Myrick JT, Pryor RJ, Palais RA, Ison SJ, Sanford L, Dwight ZL, et al. Integrated Extreme Real-Time PCR and High-Speed Melting Analysis in 52 to 87 Seconds. Clin Chem. 2019;65(2):263–71. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2018.296608.

Ye X, Fang X, Li Y, Wang L, Li X, Kong J. Sequence-Specific Probe-Mediated Isothermal Amplification for the Single-Copy Sensitive Detection of Nucleic Acid. Anal Chem. 2019;91(10):6738–45. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.9b00812.

Liu C, Shi C, Li M, Wang M, Ma C, Wang Z. Rapid and simple detection of viable foodborne pathogen Staphylococcus aureus. Front Chem. 2019;7:124. https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2019.00124.

Zhang M, Wang X, Han L, Niu S, Shi C, Ma C. Rapid detection of foodborne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes by strand exchange amplification. Anal Biochem. 2018;545:38–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2018.01.013.

Shi C, Shang F, Zhou M, Zhang P, Wang Y, Ma C. Triggered isothermal PCR by denaturation bubble-mediated strand exchange amplification. Chem Commun. 2016;52(77):11551–4. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6CC05906F.

Liu S, Wei M, Liu R, Kuang S, Shi C, Ma C. Lab in a Pasteur pipette: low-cost, rapid and visual detection of Bacillus cereu using denaturation bubble-mediated strand exchange amplification. Anal Chim Acta. 2019;1080:162–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2019.07.011.

Li M, Liu M, Ma C, Shi C. Rapid DNA detection and one-step RNA detection catalyzed by Bst DNA polymerase and the narrow-thermal-cycling. Analyst. 2020;145(15):5118–22. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0AN00975J.

Deng J, Li Y, Shi W, Liu R, Ma C, Shi C. Primer design strategy for denaturation bubble-mediated strand exchange amplification. Anal Biochem. 2020;593:113593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2020.113593.

Rodríguez A, Rodríguez M, Córdoba JJ, Andrade MJ. Design of primers and probes for quantitative real-time PCR methods. PCR Primer Design: Springer; 2015. p. 31–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2365-6_3.

Kwok S, Kellogg DE, McKinney N, Spasic D, Goda L, Levenson C, et al. Effects of primer-template mismatches on the polymerase chain reaction: human immunodeficiency virus type 1 model studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18(4):999–1005. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/18.4.999.

Meyer SPM, Unger WWJ, David N, Christoph B, Cornelis V, Van RAMC. Infection with and Carriage of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in Children. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:329. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00329.

Petrone BL, Wolff BJ, Delaney AA, Diaz MH, Winchell JM. Isothermal Detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae Directly from Respiratory Clinical Specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(9):2970–6. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01431-15.

Diaz MH, Cross KE, Benitez AJ, Hicks LA, Kutty P, Bramley AM, et al. Identification of Bacterial and Viral Codetections With Mycoplasma pneumoniae Using the TaqMan Array Card in Patients Hospitalized With Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Open Forum Infect Di. 2016;3(2). https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofw071.

Tomita N, Mori Y, Kanda H, Notomi T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) of gene sequences and simple visual detection of products. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(5):877–82. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2008.57.

Wong YP, Othman S, Lau YL, Son R, Chee HY. Loop Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP): A Versatile Technique for Detection of Microorganisms. J Appl Microbiol. 2018;124(3):626–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.13647.

Daniel A, Ginesta MM, Mireia G, Francisco RM, Joan F, Juli B, et al. Nanofluidic Digital PCR for KRAS Mutation Detection and Quantification in Gastrointestinal Cancer. Clin Chem. 2012;58(9):1332–41. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2012.186577.

Lee J, Cheglakov Z, Yi J, Cronin TM, Gibson KJ, Tian B, et al. Plasmonic Photothermal Gold Bipyramid Nanoreactors for Ultrafast Real-Time Bioassays. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139(24):8054–7. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.7b01779.

Chang HY, Chang LY, Shao PL, Lee PI, Chen JM, Lee CY, et al. Comparison of real-time polymerase chain reaction and serological tests for the confirmation of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children with clinical diagnosis of atypical pneumonia. J Microbiol Immunol. 2014;47(2):137–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2013.03.015.

Williamson J, Marmion BP, Worswick DA, Kok TW, Tannock G, Herd R, et al. Laboratory diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. 4. Antigen capture and PCR-gene amplification for detection of the mycoplasma: problems of clinical correlation. Epidemiol Infect. 1992;109(3):519–37. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0950268800050512.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Programs of China (2018YFE0113300) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21675094, 31670868).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chen Yang and Jie Deng performed the experiments; Chen Yang, Yang Li and Jie Deng analyzed the data; Yang Li, Cuiping Ma and Chao Shi designed the study; Yang Li, Chen Yang and Mengzhe Li wrote the manuscript; and all authors contributed to the writing of the paper, had primary responsibility for the final content, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics approval

The authorized Human Health and Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University approved this study, and all methods were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent to participate

All donors of clinical sputum specimens provided informed consent.

Consent for publication

All the authors and participants consent to publication of this manuscript in Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, C., Li, Y., Deng, J. et al. Accurate, rapid and low-cost diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae via fast narrow-thermal-cycling denaturation bubble-mediated strand exchange amplification. Anal Bioanal Chem 412, 8391–8399 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-020-02977-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-020-02977-y