Abstract

Spin-spiral multiferroics exhibit a magnetoelectric coupling effects, leading to the formation of hybrid domains with inseparably entangled ferroelectric and antiferromagnetic order parameters. Due to this strong magnetoelectric coupling, conceptually advanced ways for controlling antiferromagnetism become possible and it has been reported that electric fields and laser pulses can reversibly switch the antiferromagnetic order. This switching of antiferromagnetic spin textures is of great interest for the emergent field of antiferromagnetic spintronics. Established approaches, however, require either high voltages or intense laser fields and are currently limited to the micrometer length scale, which forfeits the technological merit. Here, we image and control hybrid multiferroic domains in the spin-spiral system TbMnO3 using low-temperature electrostatic force microscopy (EFM). First, we show that image generation in EFM happens via surface screening charges, which allows for probing the previously hidden magnetically induced ferroelectric order in TbMnO3 (PS = 6 × 10−4 C/m2). We then set the antiferromagnetic domain configuration by acting on the surface screening charges with the EFM probe tip. Our study enables detection of entangled ferroelectric and antiferromagnetic domains with high sensitivity. The spatial resolution is limited only by the physical size of the probe tip, introducing a pathway towards controlling antiferromagnetic order at the nanoscale and with low energy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magnetoelectric multiferroics allow controlling one order parameter by influencing another, opening pathways to affect forms of ferroic order, which are not accessible to external manipulation in conventional ways. This enables conceptually advanced ways for controlling ferroic domains, which is crucial for modern technology. Recently, magnetoelectric multiferroics moved into focus because of their inherent capability for controlling antiferromagnetic order by electric fields1. In contrast to ferromagnets, the net magnetisation of antiferromagnetics cancels out so that stored information is inherently protected against perturbations by external magnetic fields. Because of this outstanding robustness, antiferromagnets hold great promise for the design of next-generation non-volatile memory technology2,3,4,5,6.

A particularly strong one-to-one coupling between magnetic and electric order occurs in so-called spin-spiral multiferroics. In spin-spiral multiferroics, the emergence of non-collinear spin textures breaks inversion symmetry and, thereby, induces ferroelectric order7,8. Prominent compounds that fall into this class of materials are TbMnO39,10,11, Ni3V2O812 and MnWO413,14. Each of these materials develops hybrid multiferroic domains, that is, with inseparably entangled electric and magnetic degrees of freedom15. Application of an electric field can thus influence the antiferromagnetic domain pattern, for example, by driving these systems into a single-domain state11,16 or switching between single-domain states with spin cycloids of opposite helicity17. A recent breakthrough towards local control of antiferromagnetism was the demonstration of sequential optical writing and erasing of micrometre-sized multiferroic domains in TbMnO318. However, while these experiments showed the general possibility to reversibly switch antiferromagnetic order by light, the applied approach is specific to a certain configuration of material parameters, imposing strong boundary conditions for the utilisation of optical domain control.

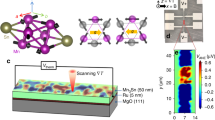

Here, we demonstrate local electric-field control of hybrid multiferroic domains in orthorhombic TbMnO3. Below 27 K, TbMnO3 forms a spin cycloid (zero net magnetic moment). This type of antiferromagnetic order is characterised by a spin chirality C = Si × Sj and the distance unit vector eij linking neighbouring spins Si and Sj (Fig. 1a). The spin cycloid breaks inversion symmetry and induces a polarisation P ∝ eij × (Si × Sj) along the c axis, thus establishing the multiferroic phase10,16,19. Depending on the sense of chirality, the polarisation points up or down leading to a rigid connection between the polarisation and antiferromagnetic structure. Upon heating, the material undergoes a phase transition to an incommensurate antiferromagnetic (AFM) phase, with sinusoidally modulated spins and zero polarisation, and, subsequently, at 42 K, a transition into the paramagnetic state (PM)11.

a Illustration of the rigid link between chirality (C) of the spin spiral and induced polarisation (P) direction. The spins Si and Sj (orange arrows) rotate in the bc-plane forming a clockwise (↻) or anticlockwise (↺) spin spiral. The polarisation is determined by P ∝ eij × C with the unit vector eij linking neighbouring spins (Graphic adapted from ref. 18). b Working principle of the EFM method used in this paper. A positive charge qtip at the tip experiences different overall forces depending on the surface charge qS and the mirror charge qm (induced by the tip voltage). The graphic shows a negative or positive net surface charge for down or up polarisation leading to an attractive (\({F}_{s}^{{\rm{attr}}}\)) or repulsive force (\({F}_{s}^{{\rm{rep}}}\)), respectively, due to an under-screening of the surface. The mirror charge always leads to an attractive force (\({F}_{m}^{{\rm{attr}}}\)).

Using low-temperature electrostatic force microscopy (EFM), we probe the ferroelectric component of the hybrid multiferroic domains via complimentary screening charges formed at the surface. This approach removes the need to resolve the piezoresponse associated with the magnetically induced polarization, which so far hampered the visualization of hybrid multiferroic domains by scanning-probe microscopy. In contrast to previous measurements by X-ray20 and nonlinear optical methods17, our EFM measurements allow nanoscale resolution of the hybrid multiferroic domains. By applying a voltage as low as 3 V to the probe tip, we can manipulate the distribution of surface charges and thus the ferroelectricity, and trough their rigid coupling to the spin system, create antiferromagnetic domain patterns in arbitrary geometries, benefiting from the nanoscale spatial precision offered by scanning-probe microscopes.

Results

Detection of multiferroic hybrid domains

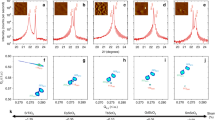

We perform low-temperature EFM measurements on a c-oriented out-of-plane-polarised bulk sample of TbMnO3 using a cryogenic scanning-probe microscope (see Methods). EFM is sensitive to electrostatic properties, including changes in surface potential as well as bound or free charges. The basic working principle of the EFM method used in this work is shown in Fig. 1b. Charge at the tip (qtip) interacts with the surface charge (qS) and the mirror charge generated by the tip (qm). Depending on the sign of the surface charge, the tip experiences an either ‘more attractive’ or ‘more repulsive’ overall force Fs + Fm (Fig. 1b shows the example of a positively charged tip)21. The corresponding force is detected as a phase shift in the tip oscillation, which is due to a change in resonant frequency of the tip (more information on the tip-sample interaction can be found in the Supplementary Fig. 2). This allows us to indirectly image the surface polarisation. Figure 2a–c shows three EFM images recorded in the multiferroic phase, the AFM phase with zero polarisation and the PM phase. The EFM images are recorded for decreasing temperatures with a holding time of 3–4 h at each temperature. A flat EFM signal is detected in the PM as well as the AFM phase (Fig. 2b, c); only in the multiferroic phase with P ≠ 0, a pronounced structure appears (Fig. 2a). See Supplementary Fig. 1 for an evaluation of the signal-to-noise ratio of the EFM images.

EFM signal in the multiferroic (a), AFM (b) and in the PM (c) phase of TbMnO3 (c-cut, tip voltage 1 V, tip-surface distance 30 nm). The scale bar corresponds to 5 μm. d Polarisation determined by pyrocurrent measurements (black line; left axis) and EFM signal determined by the contrast between dark and bright domains (orange dots; right axis) as a function of temperature.

The magnitude of the contrast between the bright and dark areas in the EFM images is shown in Fig. 2d as a function of temperature. In addition to the EFM measurements, we determine the spontaneous electric polarisation of the sample by pyroelectric current measurements (Fig. 2d). A transition temperature of Tc = 28.5 ± 1 K as well as a spontaneous polarisation of PS = 6.6 × 10−4 C/m2 at 9 K can be determined from pyroelectric experiments (see Methods) in agreement with previous studies (pyroelectric measurements8,9; P-E loops22; measurements of the ferroelectric phase transition by applying a magnetic field23). The comparison of the EFM signal and pyroelectric current data shows that the contrast in Fig. 2a relates to the onset of ferroelectric order. Additionally, reversing the tip voltage leads to a reversed domain contrast, confirming that the signal is of electrostatic origin (Supplementary Fig. 2). Additional surface potentials may create an additional homogeneous background, acting as an additional charge on the tip. The latter manifests as a shift in the voltage at which the contrast inversion occurs, but does not alter the results qualitatively (see Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). This leads us to the conclusion that dark and bright areas in Fig. 2a correspond to hybrid multiferroic domains, imaged via their ferroelectric component.

Microscopic origin of EFM contrast

To scrutinise the origin of the pronounced EFM contrast further, we record a sequence of EFM images above and below the multiferroic transition temperature (Fig. 3). Prior to each of the consecutive measurements, the sample is cooled into the multiferroic phase to a temperature of 20 K and then heated to the respective temperatures above the transition temperature. This procedure is sketched in Fig. 3g and applied in the range from 30 to 70 K in 5 K steps. Each heating and cooling cycle requires approximately 3 h. Representative images from the data acquisition sequence are shown in Fig. 3a–f.

a–f Representative EFM images in the multiferroic phase (20 K) and above Tc (all images are taken at the same position). Tip voltages are chosen to produce the best contrast and are 2 V (a), 0 V (b), −2 V (c), 0 V (d), 0 V (e) and −4 V (f). See Supplementary Fig. 2 on a more detailed discussion on the implications of tip voltage and surface potential on the EFM signal. For temperatures above Tc, no voltage is applied to the tip in order to minimise the impact of the tip on the electrostatic potential of the sample. The length of the scale bar is 3 μm. g Schematic sketch of the thermal annealing protocol (blue line) and the two temperature regimes identified in this work: up to 50 K the domain pattern is preserved; above 50 K the domain structure changes (the time for each heating and cooling cycle is ~3 h).

EFM images in Figs. 3a–c show the effect of thermal cycling between 20 and 30 K for the initial domain structure (a), an image recorded in the same area above Tc (b) and again the same area after cooling back to 20 K (c). Interestingly, despite heating into the paraelectric (AFM) phase, the same pattern is observed in all three images. Once established, the EFM contrast pattern persists above the transition temperature and remains unchanged when re-entering the multiferroic phase. This behaviour can be observed up to about 50 K (Fig. 3g) in the PM phase. From about 60 K upwards (Fig. 3d), the contrast pattern begins to change when cooled back to the ferroelectric state. At 65 K (Fig. 3e) the EFM contrast has vanished entirely and subsequent cooling below Tc leads to a completely different multiferroic domain pattern (Fig. 3f).

As the multiferroic transition temperature Tc is unambiguously identified by the emerging ferroelectric order at 27 K (Fig. 2d), the observed contrast at higher temperatures cannot be caused by residual hybrid multiferroic domains in TbMnO3. Notably, the domain-like pattern above the transition temperature is only observed when the sample has previously been cooled below the transition temperature, whereas it is not observed during the initial cool-down. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the EFM signal above Tc is due to residual screening charges remaining on the surface after the polarisation has disappeared. Persistence of the EFM signal up to 60 K indicates very low mobility of these screening charges and thus a slow deterioration. This can be readily tested since the residual screening charge is not pinned by polarisation and thus is expected to decay over time24.

Hence, Fig. 4a shows the time-dependent evolution of the EFM signal at 35 K. Its magnitude is derived from the signal difference between the dark and bright domains. This value decays exponentially with a mean lifetime of 8.37 ± 0.29 h, during which time the domain-imprinted pattern remains unchanged, which corroborates our hypothesis that the observed EFM signal is due to screening charges with low mobility.

a Time dependence of the signal difference between the bright and dark domains at 35 K. The measured contrast decays exponentially (the black line is a fit to the measured data points (orange)). b and c show the same area below and above Tc, respectively, measured with the same voltage of 5 V applied to the tip. The same pattern, but with reversed contrast is measured. One exemplary region is highlighted by a white dotted line. The scale bar corresponds to 3 μm. d Schematic sketch of the charge distribution in the multiferroic and paraelectric phase. The circled charges on the surface represent the screening charges, the charges depicted inside the material are induced by the polarisation. The total charge in each area reverses its sign upon crossing the multiferroic transition temperature.

To probe the behaviour and dynamics of the screening charges further, we record EFM images below and above the transition temperature with the same tip voltage (see Fig. 4b, c). Images in Fig. 4b, c show the same area at 20 K and 35 K. Both temperatures show the same pattern, however, with a reversed contrast (highlighted by the white dotted line). The reversal occurs because above Tc, the surface hosts residual screening charges due to the previous presence of ferroelectric polarisation, whereas below Tc, the surface polarisation is now under-screened due to a slow reacquisition of screening charges subsequent to their interim decay/degradation above Tc (mechanism sketched in Fig. 4d)24. Thus a similar exponential decay of the EFM signal as in Fig. 4a can also be seen at 20 K, where it corresponds to a slow acquisition of screening charges to compensate the ferroelectric polarisation (see Supplementary Fig. 5).

Electric control of antiferromagnetic domains

After establishing the origin of our EFM signal, we use mobile charges at the sample surface to control the hybrid multiferroic domains via local electric-field cooling. In contrast to hysteretic electric field switching, the electric field required to orient the domains while cooling through the phase transition is much smaller and previous studies demonstrated that electric fields of 2–3 kV/cm, are sufficient to drive TbMnO318,23 into a macroscopic single-domain state. Figure 5a depicts the domain pattern at 20 K. After imaging, the temperature is increased to 40 K and a 2 × 2 μm2 box is written onto the sample surface with 3 V applied to the EFM tip as illustrated in Fig. 5b. By applying a voltage above Tc to the EFM tip while in contact with the sample surface, the screening charges can be influenced by the electric field25,26 or the pressure exerted by the tip27, leading to a redistribution of existing surface charges and/or charge injection. Then, the temperature is reduced to 20 K and the same surface area is imaged again by EFM (Fig. 5c). The domain pattern in the region where no tip voltage was applied remains the same, whereas a bright domain appears where the voltage was applied. Additionally, the bright square is surrounded by a predominately dark region of oppositely polarised domains, whereas the distribution further away remains the same. This behaviour can be explained based on the minimization of electric stray fields, which can only be achieved via a rearrangement of the domains around the switched area, as the polarization state of the manipulated area is stabilized by the persistent surface charges. Furthermore, the EFM contrast level (bright) in the manipulated region is comparable to other domains with the same orientation (Supplementary Fig. 6), which shows that contributions from the polarisation orientation play a dominant role, without any sign of pronounced additional contributions from, e.g. charged adsorbents or charges manipulated by the tip.

The EFM images in a and c were taken with 3 V applied to the tip and are shown before and after a square box with 3 V applied to the tip was written onto the surface at 40 K (b). To be able to compare both images we reversed the contrast in image (c) as it was originally measured with −3 V (see Supplementary Fig. 2 for reversed contrast under opposite voltage). The scale bar corresponds to 3 μm.

To analyse the precision with which we can write domains, we compare the distances across which the contrast changes from bright to dark for the written box-shaped domain and naturally occurring domains (Supplementary Fig. 6). We find that this distance is about 800 nm for both our written domains and the naturally occurring ones. As the width of domain walls in spin-spiral multiferroics is well below this value28, this demonstrates that we are resolution limited by the EFM experiments, with 800 nm giving an upper bound for the precision with which domains can be controlled. In Supplementary Fig. 7, we show that domains can also be written without entering the multiferroic phase first, which indicates that residual screening charges are not required to write domains. Possible mechanisms that can lead to the observed effect, but which we cannot distinguish in the EFM experiment, are a redistribution of existing charges that cause the aforementioned homogeneous surface potential and/or charge injection from the bias tip. Concerning the thermal stability, we observe the same behaviour for the written charges as for the residual ones as presented in Supplementary Fig. 8. Thus, by electrically modifying the local surface potential (via the redistribution of mobile surface charges and/or charge injection) we can efficiently influence the multiferroic domain pattern. Hence, the antiferromagnetic order can be manipulated by thermal cycling combined with a small seed voltage (local electric-field cooling) through a coupling to the ferroelectric order, whereas direct poling in the multiferroic phase would require impractically large fields.

Discussion

Our experiments show that we can visualise the hybrid multiferroic domains by EFM via the ferroelectric order of TbMnO3 at low temperatures. An EFM signal is utilised through an imbalance between the polarisation and the screening charges due to the low charge carrier mobility of the material. The contrast pattern imprinted by the domains can be observed even above the multiferroic transition temperature, which we attribute to the persistence of screening charges in the paraelectric state. Manipulation of charges at the sample surface above the transition temperature allows to realise local electric-field cooling to influence the hybrid multiferroic domains with voltages on the scale of a few volts. Our approach thus allows us to switch antiferromagnetic domains of opposite chirality at low energies.

Thus, utilizing the one-to-one coupling between electric and magnetic order in TbMnO3, we manipulate the antiferromagnetic order using the probe tip of an atomic-force microscope. Being resolution limited with respect to the imaging of the manipulated area, it is possible to give an upper bound of about 800 nm for the precision with which domains can be manipulated. However, as the area where the surface charge state is controlled correlates with the diameter of the probe, it is reasonable to assume that the accuracy of the actual writing procedure can reach ≈10 nm (size of commercially available tips). The potential to control domains at the nanometre length scale could be a crucial step towards the realisation of antiferromagnetic memory devices. Antiferromagnetic memory devices are predicted to have an increased speed of operation, are robust against external perturbations and could have higher storage densities. These abilities make them very attractive for industry and could result in future antiferromagnetic data storage devices.

Methods

Electrostatic force microscopy

Electrostatic force microscopy (EFM) measurements were performed with a low-temperature atomic-force-microscopy system (attocube attoLIQUID2000). We use an oscillating platinum-coated tip, which is scanned across the material at a constant distance of 10–30 nm from the surface. In all experiments, the sample is grounded and a voltage is applied to the tip. The interaction between the charge on the tip and the charge on the sample results in a charge-dependent signal recorded as a change in phase shift of the cantilever oscillation (see Fig. 1b). The TbMnO3 sample investigated is a crystal of size 0.5 × 10 × 10 mm3 grown by the floating zone method. A face of the crystal perpendicular to the c-direction was chemo-mechanically lapped and polished for EFM measurements, with the ferroelectric polarisation pointing out of the measurement plane.

Pyroelectric current measurements

In addition to the EFM measurements, we determined the polarisation strength of the sample by pyroelectric current measurements. Silver-paste electrodes were applied on the ab plane and their size was optically determined. Then the sample was field cooling in E = 0.3 kV/mm from 50 to 9 K. At 9 K the electrods were grounded before we connected them to an electrometer (Keithley 6517B). The pyroelectric current was then determined by measuring the current between the electrodes under a heat rate of 1 K/min. The found transition temperature Tc = 28.5 ± 1 K as well as the polarisation strength of PS = 6.6 × 10−4 C/m2 at 9 K are in good agreement with previous studies8,9.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Codes used for simulations and data evaluation are available from the sources cited and from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Feng, Z., Yan, H. & Liu, Z. Electric-field control of magnetic order: from FeRh to topological antiferromagnetic spintronics. Adv. Electron. Mater. 5, 1800466 (2019).

Marti, X. et al. Room-temperature antiferromagnetic memory resistor. Nat. Mater. 13, 367–374 (2014).

Wadley, P. et al. Electrical switching of an antiferromagnet. Science 351, 587–590 (2016).

Jungwirth, T., Marti, X., Wadley, P. & Wunderlich, J. Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 231–241 (2016).

Kosub, T. et al. Purely antiferromagnetic magnetoelectric random access memory. Nat. Commun. 8, 13985 (2017).

Jungfleisch, M. B., Zhang, W. & Hoffmann, A. Perspectives of antiferromagnetic spintronics. Phys. Lett. A 382, 865–871 (2018).

Tokura, Y., Seki, S. & Nagaosa, N. Multiferroics of spin origin. Rep. Prog. Phys. 77, 076501 (2014).

Kimura, T. Spiral magnets as magnetoelectrics. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 37, 387–413 (2007).

Kimura, T. et al. Magnetic control of ferroelectric polarization. Nature 426, 55–58 (2003).

Katsura, H., Nagaosa, N. & Balatsky, A. V. Spin current and magnetoelectric effect in noncollinear magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 057205 (2005).

Kenzelmann, M. et al. Magnetic inversion symmetry breaking and ferroelectricity in TbMnO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 087206 (2005).

Lawes, G. et al. Magnetically driven ferroelectric order in Ni3 V2 O8. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 087205 (2005).

Taniguchi, K., Abe, N., Takenobu, T., Iwasa, Y. & Arima, T. Ferroelectric polarization flop in a frustrated magnet MnWO4 induced by a magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 097203 (2006).

Meier, D. et al. Observation and coupling of domains in a spin-spiral multiferroic. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 107202 (2009).

Meier, D. et al. Topology and manipulation of multiferroic hybrid domains in MnWO4. Phys. Rev. B 80, 224420 (2009).

Yamasaki, Y. et al. Electric control of spin helicity in a magnetic ferroelectric. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 147204 (2007).

Matsubara, M. et al. Magnetoelectric domain control in multiferroic TbMnO3. Science 348, 1112–1115 (2015).

Manz, S. et al. Reversible optical switching of antiferromagnetism in TbMnO3. Nat. Photonics 10, 653–656 (2016).

Mostovoy, M. Ferroelectricity in spiral magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 067601 (2006).

Fabrizi, F. et al. Circularly polarized X rays as a probe of noncollinear magnetic order in multiferroic TbMnO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 237205 (2009).

Schoenherr, P. et al. Observation of uncompensated bound charges at improper ferroelectric domain walls. Nano Lett. 19, 1659–1664 (2019).

Aoyama, T. et al. Giant spin-driven ferroelectric polarization in TbMnO3 under high pressure. Nat. Commun. 5, 4927 (2014).

Kimura, T., Lawes, G., Goto, T., Tokura, Y. & Ramirez, A. P. Magnetoelectric phase diagrams of orthorhombic RMnO3 (R=Gd, Tb, and Dy). Phys. Rev. B 71, 224425 (2005).

Kalinin, S. V. & Bonnell, D. A. Local potential and polarization screening on ferroelectric surfaces. Phys. Rev. B 63, 125411 (2001).

Chen, X. Q. et al. Surface potential of ferroelectric thin films investigated by scanning probe microscopy. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 17, 1930 (1999).

Kim, Y. et al. Effect of local surface potential distribution on its relaxation in polycrystalline ferroelectric films. J. Appl. Phys. 107, 054103 (2010).

Tong, S. et al. Mechanical removal and rescreening of local screening charges at ferroelectric surfaces. Phys. Rev. Appl. 3, 014003 (2015).

Leo, N. et al. Polarization control at spin-driven ferroelectric domain walls. Nat. Commun. 6, 6661 (2015).

Acknowledgements

P.S., S.M., L.K., M.F. and D.M. acknowledge financial support by the SNSF projects 206021_150635, 200021_149192, 200021_178825. A.I. and T.K. were supported by JSPS KAKENHI under grant numbers JP17H01143 and JP19H05823. K.S. acknowledges the support of the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Grant Agreement No. 724529) and Ministerio de Economia, Industria y Competitividad through Grant Nos. MAT2016-77100-C2-2-P and SEV-2015-0496. D.M. is supported by the Research Council of Norway (FRINATEK Project No. 263228/F20) and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) through the Onsager Fellowship Programme and the Outstanding Academic Fellows Programme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.S. and S.M. designed the experiments. P.S. performed and analysed all experiments. K.S. performed all simulations. P.S., L.K., D.M. and M.F. wrote the paper and discussed the results. A.I. and T.K. provided the samples.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schoenherr, P., Manz, S., Kuerten, L. et al. Local electric-field control of multiferroic spin-spiral domains in TbMnO3. npj Quantum Mater. 5, 86 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-020-00289-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-020-00289-z

This article is cited by

-

Stabilizing electromagnons in CuO under pressure

npj Quantum Materials (2023)