Abstract

One in eight children aged 5–19 years in the UK suffer from a psychiatric disorder, while fewer than 35% are identified and only 25% of children access mental health services. Whilst government policy states that primary schools are well-placed to spot the early warning signs of mental health issues in children, the implementation of early identification methods in schools remains under-researched. This study aims to increase understanding of the acceptability and feasibility of different early identification methods in this setting. Four primary schools in the East of England in the UK participated in a qualitative exploration of views about different methods that might enhance the early identification of mental health difficulties (MHDs). Twenty-seven staff and 20 parents took part in semi-structured interviews to explore current and future strategies for identifying pupils at risk of experiencing MHDs. We presented participants with four examples of identification methods selected from a systematic review of the literature: a curriculum-based approach delivered to pupils, staff training, universal screening, and selective screening. We used NVivo to thematically code and analyse the data, examining which models were perceived as acceptable and feasible as well as participants’ explanations for their beliefs. Three main themes were identified; benefits and facilitators; barriers and harms, and the need for a tailored approach to implementation. Parents and staff perceived staff training as the most acceptable and feasible approach to systematic identification, followed by a curriculum-based approach. Universal and selective screening garnered mixed responses. Findings suggest that a systematic and tailored approach to early identification would be most acceptable and feasible, taking into consideration school context. Teacher training should be a core component in all schools.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One in eight children aged 5–19 years suffer from psychiatric disorder and many more experience symptoms that, whilst not reaching the threshold of clinical disorder, are a source of distress for children and their families (Sadler, Vizard, Ford, Goodman, & McManus, 2018). Only 25% of children with clinically impairing psychiatric disorders receive specialist care (Sadler et al., 2018), and teachers are consistently reported to be the commonest ‘mental health service’ contacted in relation to mental health (Ford, Hamilton, Meltzer, & Goodman, 2007; Newlove-Delgado, Moore, Ukoumunne, Stein, & Ford, 2015).

One of the key barriers to intervention is poor identification (Weist, Rubin, Moore, Adelsheim, & Wrobel, 2007; Wolpert et al., 2012). In 2015, the UK Department of Health (DOH) published a strategy for improving the provision of mental health services to children young people and families, which called for the early identification of need (DOH, 2015). This was followed by a green paper, which comprehensively outlines the vital role schools and colleges have to play in identifying and responding to MHDs (DOH & DFE, 2017).

The Role of Schools in Identifying Children at Risk of Poor Mental Health Outcomes

The World Health Organization (WHO) has recognised schools as a ‘key setting’ for promoting the physical and mental health of young people (Jones & Furner, 1998). A Lancet review of school-based mental health provision highlighted future research on processes and mechanisms to identify children at risk of MHDs as a priority for maximising the effectiveness of school-based interventions (Fazel, Hoagwood, Stephan, & Ford, 2014). The integration of mental health services into the school system was reported as a key factor, whereby integrative strategies would increase access to mental health support when required.

There is already an established practice of systematic school-led identification of physical health problems via the conduct of physical health checks for 4–5 and 10–11 year olds (Kipping, Jago, & Lawlor, 2008). The UK’s current guidance on social and emotional wellbeing in primary schools, issued by the National Institute of Health and Social Care Excellence (NICE),sets out the expectation that teachers and school staff should be trained to identify and assess early signs of MHDs (NICE, 2008; Eklund & Dowdy, 2014). However, there is limited guidance with respect to how they should do this (Weare, 2015).

In the UK, most schools aspire to help pupils with emotional and behavioural difficulties through preventative or early intervention initiatives before significant problems arise (Vostanis, Humphrey, Fitzgerald, Deighton, & Wolpert, 2013). Whilst there is significant effort across schools in the UK to use systematic methods of identifying children who may benefit from more targeted forms of support (Marshall, Wishart, Dunatchik, & Smith, 2017), school staff feel ill-equipped to identify children with a mental health disorder. Parental and teacher concern is a poor predictor of clinical need (Mathews, Newlove-Delgado, & Finning, 2020). Furthermore, only 23% of schools staff believe that there is appropriate support available to help classroom teachers to identify mental health issues, and only 35% feel confident in helping children access support following identification (Day, Blades, Spence, & Ronicle, 2017). Other barriers to systematic approaches to identification have been reported, such as the concern of inaccurate identification, stigmatisation, and low availability of follow-up care (Soneson et al., 2018).

Evidence on Systematic School-Based Methods of Identification

Well-designed programs to identify children and adolescents at-risk of, or experiencing poor mental health show promise for improving detection and referral to intervention, and may improve the mental health outcomes of evidence-based intervention (D’Souza C.M., Forman S., & Austin, 2004; Allison, Nativio, Mitchell, Ren, & Yuhasz, 2014; Husky, Sheridan, McGuire, & Olfson, 2011; Mitchell et al., 2012; Wener-Siedler, Perry, & Calear, 2017). There are a range of approaches to systematic identification in school settings, each with its strengths and weaknesses. A recent systematic review (Anderson et al., 2018) identified and summarised the evidence on effectiveness for four key approaches.

Anderson et al. (2018) reported that one of the most commonly used methods is teacher nomination, where classroom teachers are given a brief description of possible behavioural and emotional manifestations of a problem (e.g. Ollendick, Greene, Weist, & Oswald, 1990) and are asked to nominate 3–10 children in their class who they believe exhibit the described symptoms. However, studies have found that teachers routinely under-identify students with internalising problems and depression, therefore limiting its utility when used in isolation (Cartwright-Hatton, McNicol, & Doubleday, 2006; Cunningham & Suldo, 2014; Dowdy, Doane, Eklund, & Dever, 2011; Horwitz et al., 2007).

Curriculum-based identification involves the delivery of information about symptoms of MHDs to pupils and encouragement to speak to a designated member of school staff should they consider themselves or another student as having MHDs. The SEYLE study (The Saving and Empowering Young Lives in Europe) found that the curriculum-based intervention programme was over 100% more effective in reducing the incidence of suicide attempts and severe suicide ideations compared to the control condition (Wasserman et al., 2015). However, evidence to date does not report on the acceptability, feasibility and effectiveness of curriculum-based approaches in identifying students presenting with the early signs of emotional difficulties.

Staff training programmes provide all or selected members of school staff with training on prevention of MHDs. Training can be delivered by an internal member of staff or external professional with relevant expertise. Students identified by staff members as having MHDs are interviewed by a designated member of staff who determines whether referral to relevant supportive services is necessary and notifies parents. Studies that examined the effectiveness of staff training reported improvements to accurate identification of students with adverse childhood experiences, anxiety and ADHD (Awadalla, Ali, Elshaer, & Eissa, 1995; Hillman & Siracusa, 1995). However, this evidence is limited when compared to research on screening programmes that seek to identify a broad range of MHDs (Vander Stoep et al., 2005). Interventions need to be tested in real-world settings to identify facilitators and barriers in different school contexts (Neil & Christensen, 2007).

Universal screening is one strategy that has received significant attention in the USA and which has generated interest in the UK (Humphrey & Wigelsworth, 2016; Williams, 2013a, Williams, 2013b). This approach involves the administration of questionnaires to all pupils about their emotional health and wellbeing. A recent systematic review (Anderson et al., 2018) indicated that universal screening can identify a proportion of children who would not be detected using less formal methods (Eklund & Dowdy, 2014; Eklund et al., 2009), and increases the referral to and uptake of supportive services (Cuijpers, Van Straten, Smits, & Smit, 2006).

Although there have been calls for the introduction of school-based universal screening in the UK as a strategy for enhancing the prevention of mental health problems and narrowing the treatment gap (Humphrey & Wigelsworth, 2016; Williams, 2013a, Williams, 2013b), there is a lack of published research evaluating the effectiveness of this approach in a UK context (Anderson et al., 2018). Furthermore, there is a lack of evidence on the acceptability and feasibility of school-based identification methods (Soneson et al., 2020).

Only a handful of studies have evaluated the acceptability of mental health screening in schools, finding that in general few parents withdraw consent for screening and that parents are generally comfortable with completing standardised measures (Beatson, 2014; Fox, Eisenberg, McMorris, Pettingel, & Borowsky, 2013; Edmunds, Garratt, Haines, & Blair, 2005). Studies considering the acceptability of suicide screening in American high schools showed that school heads, staff and young people themselves perceived universal screening programmes as the least acceptable method of identification (in comparison to curriculum-based approaches and staff training programmes), due to time burden and intrusiveness (Miller, Tanya, DuPaul, & White, 1999; Eckert, Miller, Dupaul, & Riley-Tillman, 2003; Severson, Walker, Hope-Doolittle, Kratochwill, & Gresham, 2006). In contrast, parents are largely supportive of such programmes (Fox et al., 2013). A recent survey of parents with children attending four primary schools in the East of England reported universal screening as an acceptable and viable prospect from the perspective of parents, although a significant minority of those sampled thought it could be harmful (Soneson et al., 2018). However, this study did not ask parents about their preference for universal screening in relation to other methods of identification.

Less research considers the feasibility of universal screening as a method of identification (Severson et al., 2006). A scoping review (Anderson, Howarth, Vainre, Jones, & Humphrey, 2017) identified 24 studies evaluating some aspect of universal screening, only two of which explicitly considered feasibility. One study of universal screening for emotional distress found that a shift from passive (opt out) to active (opt in) consent procedures reduced participation in screening from 85% to 66%, with the decline in participation disproportionately higher amongst pupils who were at greater risk for depression (McCormick, Thompson, Vander Stoep, & McCauley, 2009).

Acceptability and feasibility must be key considerations as well as effectiveness in the evaluation of school-based identification programmes. The World Health Organization identifies acceptability as a cornerstone of any successful screening programme (Wilson & Jungner, 1968), while the UK National Screening Committee cites acceptability as one of the key criteria that must be met before a screening programme can be implemented (Kern, George, & Weist, 2016). Acceptability is particularly important in the context of screening for MHD due to associated stigma (UK NSC recommendations; Mills et al., 2006) and significant difficulties surrounding schools’ communication and cooperation with mental health services (Ekornes, 2015).

Furthermore, the implementation of mental health interventions into real-world contexts is challenging (Regan, Lau, & Barnett, 2017). A Cochrane review of the WHO Health Promoting Schools Framework found no evidence of the effectiveness for the framework leading to improvements in pupils’ mental health, identified potential adverse effects of whole school interventions, and also stressed the need for comprehensive process evaluations (Langford, Bonell, Jones et al., 2015). It concluded that injecting multiple programs into schools without a clear understanding of implementation factors runs the risk of being costly and ineffective.

A further limitation of the literature about identification of poor mental health in schools is the failure to consider the variation of specific mental health conditions by both age and gender (Cohen et al., 1993; Merikangas et al., 2010; Wesselhoeft, Pedersen, Mortensen, Mors, & Bilenberg, 2015). Boys are more likely to develop neurodevelopmental conditions and behavioural problems, which mostly present in childhood (Jensen & Steinhausen, 2015; Zahn-Waxler, Shirtcliff, & Marceau, 2008). In contrast, internalising difficulties are more common among boys in primary school but the prevalence escalates rapidly among girls after puberty (Wesselhoeft et al., 2015; Zahn-Waxler et al., 2008: Rutter, Caspi, & Moffitt, 2003; Sadler et al., 2018). This variation by age and gender, combined with the ability for children versus adolescents to reflect on their own difficulties, suggests that we may need different strategies to optimise identification at different educational stages.

Primary schools in the UK are particularly well placed to identify and respond to early difficulties given their relatively closer ties with children and families, and an already established practice of physical health checks in England (Kipping et al., 2008). Yet, despite the potential of systematic school-based identification programmes to improve the response to children at risk of, or currently experiencing, MHDs, the evidence-base on cost effective, acceptable, and feasible methods of identification is still relatively underdeveloped, and in particular, there is an absence of UK-based studies.

Current Study

Despite the clear importance of, and recent policy focus on the early identification of MHDs, there is a paucity of evidence on the effectiveness, feasibility, and acceptability of school-based identification models, especially within the UK and in primary schools settings (Anderson et al., 2018; Fazel et al., 2014; Humphrey & Wigelsworth, 2016; Soneson et al., 2020). The current study aimed to explore the ‘in principle’ acceptability of four key methods of identification from key stakeholders in primary/elementary schools using qualitative methods. Our aim was to gather UK parent and teacher views on the relative benefits and harms of each model and to ascertain participants’ overall preference for any one of the four models. These findings form part of a wider mixed-methods project called ‘DEAL’ (Developing Early identification and Access in Learning Environments), which aims to develop an early identification programme for use in UK primary schools.

Method

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Cambridge Psychology Research Ethics Committee (PRE.2017.045). Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Participants

Schools

Participants were recruited through four participating UK primary schools in the East of England. All are situated in relatively socially deprived areas, serving communities in the bottom tertian for social deprivation with above average uptake of free school meals (approximately 19%). The English indicies of social deprivation (2019) provide a set of relative measures of deprivation for small geographical areas across England, based on seven different domains of deprivation: income, employment, education, skills and training, health and disability, crime, barriers to housing and services, and living environment deprivation. The age range of pupils at one school was 3–7 years and 4–11 years at the three other schools. Three of the schools were based in an urban areas while one was in a rural setting (see Table 1). Inspection of school websites, key documents and interviews with staff indicated that schools had different approaches to responding to MHDs. Whilst staff were aware of the importance of early identification, none of the schools had in place a systematic process for identifying MHDs.

Across the four schools, 290 parents had previously participated in a survey for the DEAL study of which 122 had indicated their willingness to be contacted by the research team for a follow-up interview (Soneson et al., 2018). An email was sent to all 122 parents inviting them to contact the primary researcher should they wish to take part in a qualitative interview, to which 24 of responded, and 20 parents agreed to be interviewed. There were no differences between those parents who consented and those that did not with regards to gender and ethnicity. The primary researcher corresponded with parents to set up a mutually convenient date and time to conduct the interview.

School staffing charts were obtained with consent of the headteacher (principal). Staff were purposively sampled to represent the range of management, teaching and non-teaching roles in each school, including the head-teacher, deputy/assistant head teacher, Special Educational Needs Co-ordinators, class room teachers representing reception, infants and juniors, teaching assistants, administrators and lunchtime supervisors. All staff approached consented to be interviewed. The diversity of participants was considered in relation to gender, age and ethnicity, to ensure as representative a sample as possible.

We conducted in-depth interviews with 19 parents and 26 school staff. The majority of parents interviewed were mothers (89%) and white British (95%). The ethnicity reflects the regional population. Most school staff were female (92%) and Table 2 describes their roles.

Measures and Procedures

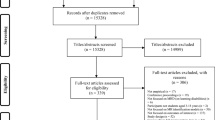

Written examples describing the four school-based early identification methods identified by our earlier systematic review were developed (Anderson et al., 2018; Fig. 1). These examples provided participants with sufficient context to understand the phenomena they were being asked to comment on. Topic guides were developed a priori from the findings of a scoping review (Anderson et al., 2017) as well as several implementation frameworks (Damschroder et al., 2009; Greenberg, Domitrovich, Graczyk, & Zins, 2005; McEvoy et al., 2014; Ozer, 2006). These topic guides contained interview questions which had a wide focus of exploring experiences and knowledge of early identification methods, as well as specific approaches. They were reviewed and refined by two advisory groups, each comprised of eight parents. Members of the advisory groups were parents of children attending a primary school in the regions, and were independent to participation in the study, in accordance with National Standards for Public Involvement in Research (2018). The focus of this paper is drawn on responses to questions in semi-structured one–one interviews, which elicited participants’ views about the acceptability and feasibility of each of the four early identification methods presented in the examples, with separate versions for parents and school staff. Participants were also asked to comment on their most and least preferred method of identification.

Summary of the four identification methods shared with participants during interviews, based on findings from Anderson et al. (2018)

Procedure

Where possible, interviews took place on school premises. Participant information sheets and consent forms were given at the start of the interviews, along with copies of the four examples of identification methods. The researcher presented the aims of the wider study and those addressed by the interview; the harms and benefits of participation were discussed, along with the participants’ right to withdraw from the interview and the study as a whole. Each participant was informed of who to talk to in the school setting if the interview raised concerns, and was given a list of local mental health resources to access if needed. Fully informed written consent was provided before proceeding with the interviews.

Interviews lasted between 40–60 min and participants received a £10 shopping voucher at the end of the interview as a token of appreciation. Participants were given examples of the four identification methods, and asked to think about benefits/facilitators and harms/barriers of each. Participants were also asked to rank the four examples in terms of their perceived ‘most preferred’ method and the ‘least preferred’ method.

Analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. NVivo V11 was used to support data management and analysis. Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) drawing on the approach of constant comparison was utilised to construct a coding framework calibrated by the research team, including inductive and deductive codes. This applied approach to thematic analysis is primarily concerned with characterising and summarising perceptions and lived experiences allowing for conceptualisation of themes as domain summaries (Guest, MacQueen, & Namey, 2012). Responses to the four examples of identification methods were analysed under the deductive themes/domains of ‘benefits and facilitators’, and ‘barriers and harms’ to implementation. Additionally, two team members inductively coded a selection of transcripts (JC-F, EH) who then met to compare and contrast the codes and develop the initial coding scheme. The codeframe and all the anonymised transcripts were coded in NVivo by JC-F. A third member of the team (A-MB) reviewed the coding and met regularly with the primary researcher to analyse the data and interpret the findings. Where there was divergence in views these were discussed and themes were reconsidered to reach consensus, in line with achieving rigour in qualitative research (Morse, 2015). Identified themes and patterns across themes were reconsidered until consensus was reached. The final theme structure was then discussed and agreed by the research team.

Findings

Thematic Findings of Identification Methods

The analysis generated three main themes that cut across the different identification methods. The themes and subthemes are listed in Table 3 and described below. The themes and subthemes represent a synthesis of themes across the four school contexts and the respondent groups.

Theme One: Benefits and Facilitators of Early Identification Programmes

In general, the identification programmes were viewed positively because they help facilitate early identification and access to timely support, and help to raise awareness about MH and reduce stigma. Each of these sub-themes are illustrated below

Facilitates Early Identification and Leads to Timely Support

Parents and staff accept or value school-based early identification programmes because they facilitate early identification and enable timely support.

“Mental health problems can be identified really early on, like with any other problem. The potential to help is so much greater than if it’s allowed to fester and continue, and if it isn’t identified until senior school or later life, because then you’ve got years and years of bad coping mechanisms to unpick, instead having put those coping mechanisms in early.” Parent, Cambridgeshire

Parents voiced strong opinions that emotional health and wellbeing should be a priority in the school curriculum so that children are educated from an early age about MH to understand their emotions, build resilience and self-regulate.

“I think, without being disrespectful to religion, but if religion can be part of the curriculum, then… Emotional health should have priority because it’s the person that you are, and that’s more important than anything and, if you are emotionally well, you do much better in everything.” Parent, Cambridgeshire

Training approaches were perceived to prepare children and staff to spot the early signs of MHDs, and increase the likelihood that children would disclose to staff as well as equip staff with the skills and knowledge to respond to such disclosures.

Parents and staff were very positive about teacher training and thought it important for accurate identification and discussion of MH with children.

“The advantages, I think, are numerous. The fact that the teachers will have that knowledge to be able to identify children very quickly, know where to go, how to support that child, who to turn to” Class teacher, Norfolk

“So definitely if all the staff are trained, there’s definitely going to be more people there to notice, more kind of skilled people to notice, to be able to identify problems. Yeah, I’d say training is always a winner” Class Teacher, Norfolk

Overall, teachers thought that training would help them to respond consistently and would empower them to know what to do in various situations. By upskilling staff, training was seen to facilitate early identification, leading to timely support.

The universal screening approach was viewed positively by parents and staff as an effective method for identifying mental health problems, particularly in those children who hide their feelings and are ‘invisible’ and may ‘slip through the net’.

“I like the school-wide screening programme, I prefer it to a selective screening programme…we know…that children have poor attendance, special educational needs, domestic abuse in the family, these are the ones that we have already identified. My worry is the ones that we’ve not identified.” Headteacher, Cambridgeshire.

“at least you find out everything…the quiet ones who don’t really want to say something… will happily read a question and tick a box” Parent, Norfolk

Raises Awareness of Mental Health and Reduces Stigma

All school-based identification methods were perceived to help raise awareness and challenge stigma around mental health. Teacher training was seen as having the potential of breaking down barriers and stigma among staff. The curriculum approach would have the benefit of teaching all children about how to express their emotions, be accepting of others and potentially increase the likelihood of children approaching staff to seek help:

“I think if it was a programme that was devised by experts and delivered by teacher…I think that…would benefit children who don’t necessarily have hugely severe problems but maybe beginning to develop some…It’s like your physical health, you teach children to eat the right foods…about…personal hygiene and keeping their diet healthy and exercise.” Class Teacher, Cambridgeshire

Staff hoped a curriculum-based method would raise awareness and help children with difficult home lives as it would explain their own parent’s MHDs:

“So big brother changes baby’s nappy and gives baby biscuits and Year 1 child biscuits. It’s the norm, he does that a lot because Mummy sleeps a lot and they don’t get to school. So a little person is unable to read those tell-tale signs that Mummy is going through a blip… Or Daddy staying up all hours of the night playing on his Playstation and drinking and not really being any part of the family because he leads this twilight life. For them to learn that would be [invaluable]” Family support worker, Norfolk.

Participants thought that universal screening could also raise awareness about mental health in schools. Administering screening questionnaires to all children has the benefit of avoiding the potential stigma for children being selected and could be positioned as a universal health check similar to UK National Health Service (NHS) physical checks carried out with all children:

“I don’t think that [universal screening] is a bad thing. They have somebody coming in from the NHS to weigh them and take their height” (Parent, Cambridgeshire)

“The approaches that we’ve used with other areas of school improvement is we do know that to have a universal approach actually is the most effective, it has the biggest impact” Headteacher, Norfolk

Familiarity

The familiarity and quality of the school–parent relationship was identified as a critical facilitator of effective systematic identification:

“I spoke to the headmistress and I spoke to a teacher.

Interviewer: What response did you get from the headteacher?

R: Oh, fantastic. The same as you always get, “We’ll keep an eye and make sure everything’s fine, and if we think there’s a problem, we’ll let you know.”

Reflecting comments about the quality of relationships between teachers and parents, the familiar relationships between teachers and children were also seen as important facilitators of effective identification:

“if that relationship was there with the child, they’re more than likely to open up than if it was a stranger. Like me going down to year one and asking a child to fill out a questionnaire, they probably won’t open up to me” Teaching Assistant, Norfolk

“she [pupil] didn’t say anything to us [parents] and she didn’t say anything to our friends, but she did say things to the teachers. She drew pictures. She talked about how worried she was, how upset she was, and then the teacher spoke to us. So, if the teacher hadn’t have had that ability, she’d [pupil] have probably just bottled that up.” (Parent, Cambridgeshire).

Some features of the approaches were already familiar to staff, such as the selective use of Strengths & Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 2001) and the Boxhall Profile (2018), as well as visual methods where children display a drawing of a ‘happy face’ or a ‘sad face’ on their desks or coat pegs.

‘Staff training’ was familiar to participants as it is embedded within school culture, such as inset days. There was a sense that a whole school approach can only serve to assist staff, and would be more likely to lead to the early identification of pupils who may be struggling.

“everyone’s included. The admin, lunch time, everybody. Definitely the whole school need to do it together, not just the teachers…. it’s teamwork. You have to be in it together” Teaching Assistant, Norfolk

Theme Two: Barriers to and Harms of Early Identification

Echoing the results of our recent systematic review (Soneson et al., 2020), perceived barriers to the implementation of early identification programmes in schools focussed on lack of time and resources, the burden of responsibility and risk, parental engagement, the need for programmes to be age appropriate and factors that impede accuracy and reliability. Perceived harms of early identification such as increasing stigma and labelling were raised.

Lack of Time and Resources

Although MH was seen as easy to integrate with physical health topics into curriculum (PSHE), both teachers and parents were concerned that there would not be enough time to include mental health education in the curriculum.

“I think the biggest factor would be time. Time fitting it into our curriculum. We’re struggling to fit everything that we need to fit into the curriculum as it is.” Headteacher, Cambridgeshire

Both teachers and parents were particularly worried about the time involved in carrying out universal screening, and wondered if this was warranted in order to identify a relatively small number of children. The extra burden on staff was also acknowledged:

“delivery time to do it and not just carrying out the questionnaire, but collating the results and analysing everything.” Class teacher, Norfolk.

“teachers end up with that responsibility, when really, it should only be their responsibility for a limited [time]…I’ve always said that schools need a dedicated mental health [staff member] … even if it’s not all the time, but there needs to be someone that you can go to” Parent, Cambridgeshire

One school mentioned how they already are working to ease pressure on staff by providing psychological supervision:

“I have organised the budget so that we pay for psychological supervision so we provide time for people to work as teams to talk to each other about things that are difficult. It’s constantly challenging people to be able to recognise their own behaviours. You’ve got to be able to get the plank out of your own eye before you get the splinter out of somebody else’s.” Headteacher, Norfolk

The implication of funding was rarely mentioned by school staff, but was considered by some parents; ‘it’s a great idea, but it’s time, money’ and ‘obviously cost’.

Some staff thought selective screening was a more acceptable and time effective approach, but placed more accountability on teachers:

“Selective screening, is dependent on the teacher being honest about whether they’re managing the class or not and, also, having the confidence to say, “This child’s having a problem and it’s not all my fault.” I’d be very reluctant to do school-wide screening. Selective screening would be more ideal, but then the onus is on the teacher to identify whether that child’s having a difficulty or not.” Class teacher, Norfolk.

This potentially highlights the as the dependence of a selective approach on the knowledge, skill and experience of the teacher lack of rigour and reliability of a selective approach.

Burden of Responsibility and Risk

Both parents and staff discussed the level of responsibility that school-based identification methods place on schools. Parents were concerned that teacher training would place a huge responsibility on school staff and maybe beyond their remit:

“But then not being funny, teachers, if they’re teaching, how are they then going to have a one on one with a child if we think there’s an issue? You should just have someone specialising in it, coming in” Parent, Norfolk

Participants were concerned about how schools would clarify the parameters of staff training in mental health and what would subsequently be expected of teachers:

“There would have to be clear guidelines about what was actually appropriate…so that all staff didn’t feel they’d become mini-little psychologists or whatever. But I think with the right training…” Deputy Head, Norfolk

Staff commented that once a child is identified as having a MHD, schools may have an ethical dilemma when deciding what level of support to provide. Support from CAMHS was often lacking due to high thresholds for access, which would leave schools with the responsibility of provision. The provision of parenting programmes was reported as one method by which schools are attempting to address these issues.

Teachers also voiced concerns about psychiatric labels going on a child’s record. These fears were around data usage and over-labelling:

“As soon as you put something on paper…A professional will read that and the next report they write is this child is being diagnosed as… and it becomes received wisdom and I think we have to really mitigate against that… work [needs to be] done around it not being used as external data and not being used to label… and I don’t think we should in any way devalue the importance of parental perception.” Headteacher, Norfolk

Many participants, especially parents, were concerned that identification programmes might cause increased and perhaps unnecessary anxiety, even ‘putting ideas in their [children’s] heads’ and potentially labelling children:

“you’ve got the problem I think of children labelling themselves or thinking they’ve got a mental disorder when they haven’t. Or putting fear into them”. School administrator, Cambridgeshire

Fears about the impact of labelling could also be seen to imply stigma around MHD.

Stigma and Parental Engagement

There was a perception that stigma associated with MHD could impact on the way in which parents would complete questionnaires, or whether they engaged at all in selective or universal screening:

“going back to the stigma of mental health and some parents, I think, are quite protective over their families and don’t want to…are a bit reluctant to ask for help. So I’m not sure how much honest opinion you would get back” Teaching Assistant, Cambridgeshire

Resonating with the theme of familiarity described above, school staff highlighted that good quality school–parent relationships can help mediate the barriers to effective systematic identification using any method, and was seen as particularly important in relation to universal screening, where explicit upfront parental consent may be needed:

“There’s that trust issue there, isn’t there? I think our parents trust that this isn’t to trip them up or to be nosy or to pry. I think our parents trust that. Something like this would be done because we want the best for their children and we want to identify and support in any way that we can. So I think if you didn’t have that kind of relationship, it would be a very different thing.” Deputy Head, Norfolk

Some parents strongly believed that schools should be trusted to screen children, and wondered why other parents would be concerned:

“For what reason would they be concerned? What is there to be concerned about? You know, it’s the wellbeing of their child. Surely that should be paramount. If they’re concerned, I’m concerned for their children.” Parent, Norfolk

On the other hand, school staff in particular felt that some parents would be reluctant to engage with any type of screening, in some cases fearing that they would be blamed by the school for their children’s difficulties

“We would get parents who would say no. Just on principle. Or they know there’s a problem and they’ve decided not to do anything.” Teaching assistant, Norfolk

Several potential reasons for parental lack of engagement were offered:

“it’s just that they know there’s a problem, but they don’t really want to go there. They don’t want to have the stigma of their child having a need like that. They think it’s their fault and it quite often isn’t, but it feels like your fault when you’re a parent, doesn’t it?” Class teacher, Cambridgeshire

“I think engagement of the families, which you probably would have to have their consent, and they’d just say no. When they’re in a good place they’ll say yes and very quickly they will turn around and be in a bad place and say no and completely withdraw…To the detriment of the family and the children, but they don’t see that because they’re so engrossed in their own needs that they’re unable to offer containment to their children. So these little people are survivors, they manage and they survive on what they have.” Family support worker, Norfolk

There were also concerns however that some parents might struggle with wording in questionnaires and letters, some of which school staff thought would never actually get home or be returned to school.

In terms of gaining consent for screening, there were mixed responses as to whether the approach would require an opt-in or opt-out approach:

“I think when it comes to individually screening children, I think it probably would be advisable to speak to the parents as well and say, “We’ve got these concerns.” I mean, I think the parents have to be included in things like that.” Parent, Cambridgeshire

The possibility of creating stigma from screening children concerned both parents and staff. For screening to be both acceptable and feasible, anonymity and confidentiality would be essential to avoid children being singled out and stigmatised. This is particularly the case for selective screening where children in particular risk groups may feel more singled out from their peers. Despite the foreseen barriers to a universal screening programme, the key to success was seen to lie in the timing of implementation and method of delivery, summed up nicely by a member of a school senior leadership team:

“I think it would depend what the screening looks like. The questions that are asked. How they’re then evaluated and shared” Teacher, Senior Leadership Team, Norfolk

These findings suggest that whilst both parents and staff perceive some potential positives of universal screening, there are perhaps many unknowns in how the process would be implemented and what the associated outcomes would be, and how these would be managed. A tentative approach to implementation is perhaps therefore warranted.

Age Appropriateness

The general consensus was that early identification programmes should be age appropriate and tailored for different age groups. For example, staff and parents were concerned that curriculum-based content and delivery could frighten or worry children about their mental health, which might escalate mental health problems among children, and was described as potentially being a ‘minefield’. For example, participants considered it inappropriate to discuss topics such as self-harm with very young children.

Of the different methods, the curriculum-based identification method was seen to offer more flexibility in terms of how content could be developed, presented and tailored specifically for different age groups. For example, education about mental health could be developed to prepare children for their transition to senior/secondary school in the UK. Age considerations would promote effective learning and minimise the risk of anxiety among children. Participants were concerned that screening questionnaires may not be suitable for very young children or children with learning disabilities:

“Obviously with the younger children we would have to read the questions to them, so that might have to be done, because they’re never particularly good at ticking boxes.” Headteacher, Cambridgeshire.

School staff suggested that screening questionnaires could be adapted to the needs and capabilities different age groups and presented visually to younger age groups. Some parents suggested setting a minimum age for screening (e.g. year 3, aged 7–8 years), but some thought that alternative methods would be needed for very young children.

Accuracy and Reliability

Concern regarding false-positives and false-negatives were common to both parent and staff accounts relating to screening. Participants highlighted that children’s emotions often fluctuate on a daily basis, and that answers to a questionnaire on a given day could therefore be an unrepresentative snapshot:

“And it can depend on the day, the time when you’re talking to a child. You know, speak to a child after they’ve just come in from playtime, the chances are, “Oh yes, I’m fine. I’m feeling great.” Do the screening after they’ve just sat their SATs, you’re going to get a completely different set, and they may not be representative of that child. I think if it’s done throughout the school year, because you could ask the teachers where they would say that child is, and then you could ask the child.” Parent, Cambridgeshire.

Staff also expressed concern about the reliability of teacher identification following training, especially in the case of children with more internalised issues who behave well in class and achieve well academically. Parents expressed concerns of whether staff were qualified to make adequate judgements about potential mental health issues in pupils.

Staff Skills and Knowledge

Some staff considered training important in order to effectively deliver MH curricula to children. Others were concerned whether they would have the skills necessary for teaching about MH and thought they would lack confidence. The theme of knowledge potentially being used without underpinning expertise was voiced by some school staff, for example a school administrator expressed the concern, “I think you could do more harm than good”. With this in mind, some suggested outside trainers or MH specialists who understand the culture of the school may be more appropriate for delivering curriculum material to children than staff.

By contrast, several participants felt that teachers could be trained to effectively deliver this type of material:

“I can’t see that it would be harmful unless it is delivered in a way that was unacceptable. You’d have to train people to deliver it…like an inset day, this is how you deliver” Teacher, Senior Leadership Team, Norfolk

Some staff members spoke of how they “know their kids” and that they would feel confident in spotting changes in children’s behaviour and emotions. In this way, selective screening with trust placed on teacher nomination of children in particular risk groups was seen as feasible.

The example of staff training specifically outlined an inclusive approach to training—of all staff in all schools—as opposed to just teachers, which was echoed by respondents.

“for all staff…because…admin, lunch supervisors as well as secretary or dinner ladies that cook here, they see the children every day…they might pick up something different… something that we hadn’t noticed or something that we hadn’t thought of” Teaching Assistant, Cambridgeshire

Lunchtime supervisors were valued for their interaction with children, as well as Teaching Assistants. However, there were concerns about where to sign post children and families for support, and that training is needed for staff in order to deal appropriately with parents. School-wide training approach should be named ‘staff training’ as opposed to ‘teacher training’, thereby underscoring the importance of whole school buy-in to upskilling staff:

“I would change ‘teacher training’ to ‘staff training’…as soon as you call anything ‘teacher training’, lots of people in school will think it’s nothing to do with them. So a professional development approach…” Headteacher, Norfolk

Theme Three: A Tailored Approach to Implementation

Participant responses did not lend to a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to the early identification of mental health issues in primary school children. A theme was identified suggesting the relevance of a ‘tailored’ approach informed by school characteristics.

Benefits of All Approaches

The final interview question asked participants which approach out of the four they preferred. Participants could see positive aspects to each of the four approaches in some regard, frequently preferring a combination of methods, as opposed to one in particular. Staff training received the most positive responses, but the other approaches were also seen to have benefits. Parents with lived experience of their own or their children’s mental health issues tended to support a combination of approaches:

“I think they definitely all need to be in place. I think there’s definitely a place for them all” Parent, Norfolk

This was often accompanied by accounts of how they felt let down by a system that lacked processes to identify and support their children’s needs or their own:

“we’ve had to fight for everything” Parent, Norfolk

Staff also voiced the benefits of the approaches:

I: “So out of the four, which one would you put at the top of your list?

R: That’s really tricky. I think probably, for us, the teacher training, at the moment. Because I think that we are very good with our safeguarding and our relationships with children… if [there is] a really good understanding [of mental health], I think you can then look at the school-wide screening and the curriculum in a little bit more depth. I think until you really know, and all of your staff really fully understand and have got it, then it’s tricky to put it into the curriculum.” Deputy Head, Norfolk

Implementing a ‘Package’ of Approaches

Participants commented on how the approaches could work in combination with one another, often depending on school context. Teacher training and selective screening were seen to be able to work together:

“The two that I like the best are, obviously, the curriculum-based and the teacher training, because I think once something’s curriculum-based, you take out that whole, “Well, I’m being targeted because I’m different.” It’s like, “Everybody’s doing this. It’s compulsory. We all have to do it,” but then I think that could then lead into the more selective screening, when it’s a case of, “Oh, we’re doing these things in class and we’re all trained to identify these things, and we identify that we need to do some more work with this child.” Class teacher, Cambridgeshire.

This was echoed by a headteacher:

“I’d be interested in the teacher training programmes for all staff and I’d be interested in the selective screening so that you could actually then dig a bit deeper with those that you actually then want to look at.” Headteacher, Norfolk.

A staff member suggested that universal screening could pave the way for a good curriculum-based prevention programme if it were used as a means of assessing needs of the student body:

“I think it [universal screening] would be helpful…so PSHE…lessons…will [plan to] address some of the issues that affect the children and I think it’s always helpful to flag up children who are having particular problems.” Class teacher, Cambridgeshire

This sub-theme illustrated that all approaches have a place in the early identification of MHDs and could be used in a way which was tailored to the individual school context.

Discussion

This is the first qualitative study in the UK to undertake an exploration of the acceptability and feasibility of different approaches to the early identification of mental health issues in primary schools. Our main aim was to gain an understanding of parent and staff perceptions of the ‘in principle’ acceptability and feasibility of different methods, to inform the development of an early identification programme.

The findings illustrate the various facilitators and barriers, and the benefits and harms associated with four early identification methods, and indicated which approaches were preferred by school staff and parents. Of all the four approaches, staff training in mental health was universally seen as beneficial and easily facilitated. It was posited as a way of upskilling all staff in schools, from lunchtime supervisors, administrators, and class teachers, to the Senior Leadership Team (SLT). The other three approaches received a more mixed response with both benefits and harms reported by both groups of respondents. A few parents were fully in favour of introducing a curriculum-based programme, and some participants responded to the idea of universal screening with trepidation, relating mainly to the resource required to implement it. Selective screening was generally met with a degree of familiarity, as it is already implemented in the school system, but with concern about its reliability.

The themes highlight the potential burden on teachers in the implementation of early identification methods. The National College for Teaching & Leadership (Matthews, Higham, Stoll, Brennan, & Riley, 2011) raised the importance of not overloading teachers but building capacity within the school through the development of leadership qualities in all staff. In this way, staff are empowered by additional skills, thus enhancing the social, moral and knowledge capital in the school (Berwick, 2014). Given the positive response to staff training, the findings suggest that the first step to systematic identification should take the form of a whole school approach to staff training in all schools, in all contexts. Training would ensure staff know the limitations to their knowledge and the boundaries to their role in the process of identification and early intervention as educators. The provision of psychological supervision to staff would also help prevent overload and burnout (Skolvolt & Starkey, 2010).

A tailored and flexible approach to systematic early identification methods

Interestingly, the findings revealed that participants rarely preferred one approach in isolation, and many voiced the advantages of a combination of several models. This is in line with research suggesting a multi-tiered system of support to the mental health agenda in schools (MTSS; e.g., McIntosh & Goodman, 2016; Kern et al., 2016). Such systems aim to reflect the level of need by tailoring prevention and intervention strategies in multiple tiers with different levels of intensity (Fabiano & Evans, 2019). For example, our findings suggest that schools with well-developed curriculum-based programmes and sufficient staff training could consider the implementation of a universal screening programme, although this may not be a viable option for a school with fewer resources. Future research would need to establish the optimum components of a universal screening approach, from the frequency of screening to the outcome measures utilised. A potential challenge to this suggestion is that this study collected individual views, which differed across participants and within schools. A tailored approach may prove challenging where there are differences in opinion.

Universal screening programmes yielded mixed perceptions, with both staff and parents identifying barriers to implementation, replicating the recent systematic review of screening methods (Soneson et al., 2020). Concerns were raised in relation to the accuracy of results. Fears about data usage, over-labelling and the stigma associated with screening programmes in schools have been reported elsewhere (Fox et al., 2013). These results suggest a more cautious approach is needed to ensure that children are not singled out or unhelpfully labelled in the process. Concerns around time constraints, teacher capacity and the method of delivery have also received attention (Peia Oakes, Lane, Cox, & Messenger, 2014). Based on our findings, the acceptability of using a selective screening method as a standalone approach was also not supported. Participants felt that it would need to be built into a whole school approach to mental health and wellbeing, leading to the conclusion that neither the universal nor selective approaches were endorsed as standalone methods.

Importance of Context

School context plays a critical role in determining acceptability and feasibility of early identification/any programme (Peckham, 2017), which was voiced by both parents and school staff. Schools differ in the degree to which awareness of and attention to children’s emotional development and needs are embedded into school culture. Schools would need to assess the level of school readiness for early identification initiatives so as to inform decisions regarding if and how systematic identification should be facilitated. Future research could explore this further.

Ethical Implications and Parental Consent

There is a great deal of research that highlights the importance of parental engagement with schools to enhance children’s learning, through mechanisms which allow for learning to continue at home (Harris & Goodall, 2009). Our findings suggest that well-developed relationships with parents are also a key mechanism in ensuring the smooth implementation of identification programmes, and this is also likely to extend to other types of mental health promotion and prevention. Evidence to date suggests that parents do not necessarily respond to school physical health interventions (Mar & Mark, 1999), therefore schools may need to work at building this relationship in order for implementation of a mental health identification programme to be effective (Kern, Mathur, Albrecht, Ploand, Roxlaski, & Skiba, 2017).

The issue of parental consent requires careful consideration. The implementation of screening for mental health issues, such as anxiety, has been reported in some studies to be acceptable to parents (Beaston, 2014; Cresswell, Waite, & Hudson, 2020; Fox et al., 2013). In general, parents rarely withdraw consent for participation in school activities such as when presented with a community based anxiety prevention programme (Beatson, 2014; Fox et al., 2013). Our findings equally suggest that most parents were positive with regards to systematic identification programmes as long as they were informed by the school and were offered an opt-out option. In contrast, and as suggested by Humphrey and Wigelsworth (2016), school staff reported that response rates would be low to any ‘screening tools/questionnaires’ sent home for parents to complete. These contrasting views emphasise the need for parental engagement before such programmes are put in place, and further research is needed to ascertain whether children, staff as well as their parents would all be required to complete screening tools/questionnaires.

UK government policy is introducing compulsory Personal, Social and Health Education (PHSE) with statutory guidance in place from the DFE from September 2020 (DFE, 2019). Ideally, PHSE would be a specialism within a proscribed and evidence-based curriculum, which speaks to concerns voiced by our participants about knowledge and expertise of school staff. The Healthy Minds trial (London School of Economics, 2020) suggests that a spiral curriculum in secondary school may improve the mental health of pupils, but there is, to our knowledge, no similar evidence for such an approach in younger children. Further research is necessary to explore the content and frequency required as well as the methods and modes of delivery.

Our study’s findings corroborated with others around concerns of the age appropriateness of topics such as self-harm (Evans et al., 2019), indicating that delivery by professionals could be beneficial. The Green Paper on transforming children’s mental health services (DOH & DFE, 2017) advised that all schools are allocated funding to develop Mental Health Support Teams as well as a designated senior lead for mental health. Research has also suggested that school-based mental health services have the highest likelihood of identifying children in need (Kern et al., 2017). However, it remains to be seen how these policies will be implemented and their impact.

Limitations

This was a small and purposive sample drawn from a particular region of the UK, as is the norm for qualitative research, so findings reflect the experience and beliefs of those interviewed and may not generalise to parents and school staff from other areas or countries. We were able to recruit a diverse sample in terms of educator roles, but our sample were mostly women and nearly all white British so cannot be taken to represent the views of male educators, fathers or those of Black Asian & Minority Ethnic (BAME) backgrounds within the four schools from which our participants were drawn. Future research may wish to consider school contexts where the majority of pupils are from diverse BAME and cultural backgrounds, to ensure all groups are represented (Goodman, Patel, & Leon, 2008).

This study looked only at the perceptions of staff and parents in primary schools. Future direction could obtain adolescent pupils’ perspectives on the assessment of the acceptability and feasibility of early identification methods. Adolescents may be able to shed light on the reported views of parents and teachers, particularly around stigma and the likelihood of responding honestly in screening methods.

Conclusions

Ascertaining the perceptions of parents and school staff of the various approaches to early identification represents an important step towards understanding which methods could be acceptable and feasible in primary school settings. Some schools are implementing systematic screening programmes with non-validated measures, and many school-based mental health programmes are not evidence-based (Vostanis et al., 2013). Our findings could assist in paving the way for an evidenced-based approach to the early identification of mental health issues in primary schools.

The findings support the acceptability and feasibility of staff training in social and emotional mental health. Facilitators and barriers are raised for all approaches of identification methods. A tailored and flexible approach to the implementation of various identification methods, moving from universal staff training through curriculum-based prevention programmes, and screening is suggested. The development and implementation of identification programmes should be carried out in partnership with school staff and parents. This study highlights divergence and convergence in parents’ and staff views, which could be taken forwards as a focal point for future research. It is suggested that well-developed implementation models are critical and should focus on barriers, such as the lack of resources and burden on school staff, highlighting issues schools may face dependent on their context. Further research in the form of piloting a model of systematic identification is necessary to ascertain feasibility and effectiveness.

References

Allison, V., Nativio, D., Mitchell, A. M., Ren, D., & Yuhasz, J. (2014). Identifying symptoms of depression and anxiety in students in the school setting. Journal of School Nursing, 30, 165–172.

Anderson, J. K., Ford, T., Soneson, E., Thompson Coon, J., Humphrey, A., Rogers, M., et al. (2018). A systematic review of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of school-based identification of children and young people at risk of, or currently experiencing mental health difficulties. Psychological Medicine, 49(1), 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718002490.

Anderson, J. K., Howarth, E., Vainre, M., Jones, P., & Humphrey, A. (2017). A scoping literature review of service-level barriers for access and engagement with mental health services for children and young people. Children and Youth Services Review, 77, 164–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.04.017.

Awadalla, N., Ali, O. F., Elshaer, S., & Eissa, M. (1995). Role of school teachers in identifying attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among primary school children in Mansoura, Egypt. 22. http://applications.emro.who.int/emhj/v22/08/EMHJ_2016_22_08_586_595.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 17 May 2017.

Beatson, R. (2014). Community screening for preschool child inhibition to offer the ‘cool little kids’ anxiety prevention programme. Infant Child Development, 23, 650–661.

Berwick, G. T. (2014). The Four Capitals: The key components of effective knowledge management, 2014, Challenge Partners, London. http://challengepartners.org/publications/view/3#.VfL-vxFVhBd.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Cartwright-Hatton, S., McNicol, K., & Doubleday, E. (2006). Anxiety in a neglected population: Prevalence of anxiety disorders in pre-adolescent children. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(7), 817–833.

Cohen, P., Cohen, J., Kasen, S., Velez, C. N., Hartmark, C., Johnson, J., et al. (1993). An epidemiological study of disorders in late childhood and adolescence: I. Age- and gender-specific prevalence. Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines, 34(6), 851–867.

Cresswell, C., Waite, P., & Hudson, J. (2020). Practitioner review: Anxiety disorders in children and young people—Assessment and treatment. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13186.

Cuijpers, P., Van Straten, A., Smits, N., & Smit, F. (2006). Screening and early psychological intervention for depression in schools: Systematic review and meta-analysis. European Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 15, 300–307.

Cunningham, J. M., & Suldo, S. M. (2014). Accuracy of teachers in identifying elementary school students who report at-risk levels of anxiety and depression. School Mental Health, 6, 237–250.

D’Souza, C. M., Forman, S., & Austin, B. (2004). Follow-up evaluation of a high school eating disorders screening program: Knowledge, awareness and self-referral. Journal of Adolescent Healh, 36, 208–213.

Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D., Keith, R., Kirsh, S., Alexander, J. A., & Lowrey, J. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4, 50.

Day, L., Blades, R., Spence, C., & Ronicle, J. (2017). Mental Health Services and Schools Link Pilots: Evaluation report. Department for Education. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/590242/Evaluation_of_the_MH_services_and_schools_link_pilots-RR.pdf.

Department of Education. (2019). Relationships Education, Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) and Health Education Statutory guidance for governing bodies, proprietors, head teachers, principals, senior leadership teams, teachers. London. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/805781/Relationships_Education__Relationships_and_Sex_Education__RSE__and_Health_Education.pdf.

Department of Health. (2015). Future in mind:Promoting, protecting and improving our children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing. London. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/414024/Childrens_Mental_Health.pdf.

Department of Health and Social Care & Department for Education. (2017). Transforming children and young people’s mental health provision: a green paper. https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/transforming-children-and-young-peoples-mental-health-provision-a-green-paper.

Dowdy, E., Doane, K., Eklund, K., & Dever, B. (2011). A comparison of teacher nomination and screening to identify behavioral and emotional risk within a sample of underrepresented students. Journal of Emotional and Behavioural Disorders, 21, 127–137.

Eckert, T., Miller, D., Dupaul, G., & Riley-Tillman, C. (2003). Adolescent suicide prevention: School psychologists’ acceptability of school-based programs. School Psychology Review, 32, 57–76.

Edmunds, S., Garratt, A., Haines, L., & Blair, M. (2005). Child health assessment at school entry (CHASE) project: Evaluation in 10 London primary schools. Child Care Health Development, 31, 143–154.

Eklund, K., & Dowdy, E. (2014). Screening for behavioral and emotional risk versus traditional school identification methods. School Mental Health, 6, 40–49.

Eklund, K., Renshaw, T., Dowdy, E., Jimerson, S., Hart, S., Jones, C., et al. (2009). Early identification of behavioral and emotional problems in youth: Universal screening versus teacher-referral identification. California School Psychology, 14, 89–95.

Ekornes, S. (2015). Teacher perspectives on their role and the challenges of interprofessional collaboration in mental health promotion. School Mental Health, 7(3), 193–211.

Evans, R., Parker, R., Russell, A. E., Mathews, F., Ford, T., Hewitt, G., et al. (2019). Adolescent self-harm prevention and intervention in secondary schools: A survey of staff in England and Wales. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 24(3), 230–238.

Fabiano, G., & Evans, S. (2019). Introduction to the special issue of School Mental Health on best practices in effective multi-tiered intervention frameworks. School Mental Health, 11(1), 1–3.

Fazel, M., Hoagwood, K., Stephan, S., & Ford, T. (2014). Mental health interventions in schools 1 Mental health interventions in schools in high-income countries. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1, 377–387.

Ford, T., Hamilton, H., Meltzer, H., & Goodman, R. (2007). Child Mental Health is Everybody’s Business: The prevalence of contact with public sector services by type of disorder among British school children in a three-year period. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 12(1), 13–20.

Fox, C., Eisenberg, M., McMorris, B., Pettingel, S., & Borowsky, I. (2013). Survey of Minnesota parent attitudes regarding school-based depression and suicide screening and education. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 17, 456–462.

Goodman, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 1337–1345.

Goodman, A., Patel, V., & Leon, D. (2008). Child mental health differences amongst ethic groups in the UK: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 8, 258.

Greenberg, M. T., Domitrovich, C. E., Graczyk, P. A., & Zins, J. E. (2005). The study of implementation in school-based preventive interventions: Theory, research, and practice. Promotion of Mental Health and Prevention of Mental and Behavior Disorders (Vol. 3). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2012). Applied thematic analysis. Thoudand Oaks: Sage.

Harris, A., & Goodall, J. (2009). Do parents know they matter? Engaging all parents in learning. Educational Research, 50(3), 277–289.

Hillman, S. J., & Siracusa, A. J. (1995). Effectiveness of training teachers to identify and intervene with children of alcoholics, abuse, and neglect. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, 41, 49–61.

Horwitz, S. M., Kelleher, K. J., Stein, R. E. K., Storfer-Isser, A., Youngstrom, E. A., Park, E., et al. (2007). Barriers to the identification and management of psychosocial issues in children and maternal depression. Pediatrics, 119, 208–218.

Humphrey, N., & Wigelsworth, M. (2016). Making the case for universal school-based mental health screening. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 2752, 1–21.

Husky, M. M., Sheridan, M., McGuire, L., & Olfson, M. (2011). Mental health screening and follow-up care in public high schools. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 50, 881–891.

Indicies of deprivation 2019: technical report. (2019). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/english-indices-of-deprivation-2019-technical-report.

Jensen, C. M., & Steinhausen, H.-C. (2015). Comorbid mental disorders in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a large nationwide study. Attention Deficit Hyperacticity Disorder, 7(1), 27–38.

Jones, J. T., & Furner, M. (1998). WHO Global School Health Initiative & World Health Organization. Health Education and Promotion Unit.

Kern, L., George, M., & Weist, M. (2016). Supporting students with emotional and behavioral problems prevention and intervention strategies. Towson: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co., Inc.

Kern, L., Mathur, S., Albrecht, S., Ploand, S., Roxlaski, M., & Skiba, R. (2017). The need for school-based mental health services and recommendations for implementation. School Mental Health, 9, 205–217.

Kipping, R. R., Jago, R., & Lawlor, D. A. (2008). Obesity in children. Part 1: Epidemiology, measurement, risk factors, and screening. BMJ, 337, a1824.

Langford, R., Bonell, C., Jones, H., et al. (2015). The World Health Organization’s Health Promoting Schools framework: a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 15, 130.

London School of Economics. (2020). Healthy Minds Trial. https://bounceforward.com/healthy-minds-research-project/.

Mar, H., & Mark, T. (1999). Parental reasons for non-response following a referral in school vision screening. Journal of School Health, 69(1), 35–38.

Marshall, L., Wishart, R., Dunatchik, A., & Smith, N. (2017). Supporting mental health in schools and colleges—Quantitative survey. London: NatCen Social Research, Department for Education.

Mathews, F., Newlove-Delgado, T., & Finning, K. (2020). Teachers’ concerns about pupil’s mental health in a cross-sectional survey of a population sample of British schoolchildren. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12390.

Matthews, P., Higham, R., Stoll, L., Brennan, J., & Riley, K. (2011). Prepared to lead: how schools, federations an chain grow education leaders. Nottingham: National College for School Leadership.

McCormick, E., Thompson, K., Vander Stoep, A., & McCauley, E. (2009). The case for school-based depression screening: Evidence from established programs. Report on Emotional & Behavioural Disorders in Youth, 9, 91–96.

McEvoy, R., Ballini, L., Maltoni, S., O’Donnell, C. A., Mair, F. S., & MacFarlane, A. (2014). A qualitative systematic review of studies using the normalization process theory to research implementation processes. Implementation Science, 9, 2.

McIntosh, K., & Goodman, S. (2016). Integrated multi-tiered systems of support: Blending RTI and PBIS. New York: Guilford Publications.

Merikangas, K. R., He, J., Burstein, M., Swanson, S. A., Avenevoli, S., Cui, L., et al. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Study-adolescent supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989.

Miller, D., Tanya, E., DuPaul, G., & White, G. P. (1999). Adolescent Suicide Prevention: Acceptability of school-based progrms among secondary school principals. Suicide Life Threat Beavior, 29, 57–76.

Mills, C., Stephan, S. H., Moore, E., Weist, M. D., Daly, B. P., & Edwards, M. (2006). The President’s new freedom commission: capitalizing on opportunities to advance school-based mental health services. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 9(3–4), 149.

Mitchell, S. G., Gryczynski, J., Gonzales, A., Moseley, A., Peterson, T., O’Grady, K., et al. (2012). Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) for substance use in a school-based program: Services and outcomes. American Journal of Addictions, 21, S5–S13.

Morse, J. M. (2015). Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Health Research, 25(9), 1212–1222.

National Institute for Health & Care Excellence. (2008). Social snd emotional wellbeing in primary school education. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph12.

National Standards for Public Involvement in Research. (2018). http://www.invo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Public_Involvement_Standards_v1.pdf.

Neil, A. L., & Christensen, H. (2007). Australian school-based prevention and early intervention programs for anxiety and depression: A systematic review. The Medical Journal of Australia, 186, 305–308.

Newlove-Delgado, T., Moore, D., Ukoumunne, O. C., Stein, K., & Ford, T. (2015). Mental health related contact with education professionals in the British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey 2004. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 10(3), 159–169.

Ollendick, T. H., Greene, R. W., Weist, M. D., & Oswald, D. P. (1990). The predictive validity of teacher nominations: A five-year followup of at-risk youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 18, 699–713.

Ozer, E. J. (2006). Contextual effects in school-based violence prevention programs: A conceptual framework and empirical review. Journal of Primary Prevention, 27, 315–340.

Peckham, K. (2017). Developing school readiness: Creating lifelong learners. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Peia Oakes, W., Lane, K. L., Cox, M. L., & Messenger, M. (2014). Logistics of behavior screenings: How and why do we conduct behavior screenings at our school? Preventing school failure. Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 58(3), 159–170.

Regan, J., Lau, A. S., & Barnett, M. (2017). Agency responses to a system-driven implementation of multiple evidence-based practices in children’s mental health services. BMC Health Services Research, 17, 671. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2613-5.

Rutter, M., Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (2003). Using sex differences in psychopathology to study causal mechanisms: Unifying issues and research strategies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44, 1092–1115.

Sadler, K., Vizard, T., Ford, T., Goodman, R. & McManus, S. (2018). Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2017: Trends and characteristics. Leeds, UK: NHS Digital. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2017/2017.

Severson, H. H., Walker, H. M., Hope-Doolittle, J., Kratochwill, T. R., & Gresham, F. M. (2006). Proactive, early screening to detect behaviorally at-risk students: Issues, approaches, emerging innovations, and professional practices. Journal of School Psychology, 45, 193–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2006.11.003.

Skolvolt, T., & Starkey, M. (2010). The three legs of the practitioner’s learning stool: Practice, research/theory, and personal life. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 40, 125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-010-9137-1.

Soneson, E., Childs-Fegredo, J., Anderson, J., Stochl, J., Fazel, M., Ford, T., et al. (2018). Acceptability for mental health screening for mental health difficulties in primary schools: A survey of UK parents. BMC Public Health, 18, 1404. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6279-7.

Soneson, E., Howarth, E., Ford, T., Humphrey, A., Jones, P. B., Thompson Coon, J., et al. (2020). Feasibility of school-based identification of children and adolescents experiencing, or at-risk of developing, mental health difficulties: A systematic review. Prevention Science, 21(5), 581–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01095-6.

The Boxhall Profile. Copyright © (2018). The Nurture Group Network Limited. All rights reserved.

Vander Stoep, A., Mccauley, E., Thompson, K. A., Herting, J., Kuo, E., Stewart, D., et al. (2005). Universal emotional health screening at the middle school transition. Journal of Emotional and Behavioural Disorders, 13, 213–223.

Vostanis, P., Humphrey, N., Fitzgerald, N., Deighton, J., & Wolpert, M. (2013). How do schools promote emotional well-being among their pupils? Findings from a national scoping survey of mental health provision in English schools. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 18(3), 151–157.

Wasserman, D., Hoven, C. W., Wasserman, C., Wall, M., Eisenberg, R., Hadlaczky, G., et al. (2015). School-based suicide prevention programmes: The SEYLE cluster-randomised, controlled trial. Lancet, 385, 1536–1544.