Abstract

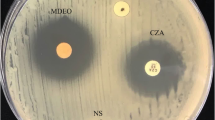

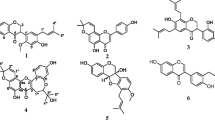

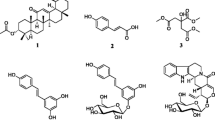

Antimicrobial resistance is increasing around the world and the search for effective treatment options, such as new antibiotics and combination therapy is urgently needed. The present study evaluates oregano essential oil (OEO) antibacterial activities against reference and multidrug-resistant clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii (Ab-MDR). Additionally, the combination of the OEO and polymyxin B was evaluated against Ab-MDR. Ten clinical isolates were characterized at the species level through multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the gyrB and blaOXA-51-like genes. The isolates were resistant to at least four different classes of antimicrobial agents, namely, aminoglycosides, cephems, carbapenems, and fluoroquinolones. All isolates were metallo-β-lactamase (MβL) and carbapenemase producers. The major component of OEO was found to be carvacrol (71.0%) followed by β-caryophyllene (4.0%), γ-terpinene (4.5%), p-cymene (3,5%), and thymol (3.0%). OEO showed antibacterial effect against all Ab-MDR tested, with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) ranging from 1.75 to 3.50 mg mL−1. Flow cytometry demonstrated that the OEO causes destabilization and rupture of the bacterial cell membrane resulting in apoptosis of A. baumannii cells (p < 0.05). Synergic interaction between OEO and polymyxin B (FICI: 0.18 to 0.37) was observed, using a checkerboard assay. When combined, OEO presented until 16-fold reduction of the polymyxin B MIC. The results presented here indicate that the OEO used alone or in combination with polymyxin B in the treatment of Ab-MDR infections is promising. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of OEO and polymyxin B association against Ab-MDR clinical isolates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All relevant data have been included in the manuscript.

References

World Health Organization (2017) Prioritization of pathogens to guide discovery, research and development of new antibiotics for drug-resistant bacterial infections, including tuberculosis

Potron A, Poirel L, Nordmann P (2015) Emerging broad-spectrum resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii: mechanisms and epidemiology. Int J Antimicrob Agents. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.03.001

Xiao SZ, Chu HQ, Han LZ et al (2016) Resistant mechanisms and molecular epidemiology of imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Mol Med Rep. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2016.5538

Alcántar-Curiel MD, García-Torres LF, González-Chávez MI et al (2014) Molecular mechanisms associated with nosocomial carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Mexico. Arch Med Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcmed.2014.10.006

Schlesinger SR, Lahousse MJ, Foster TO, Kim SK (2011) Metallo-β-Lactamases and aptamer-based inhibition. Pharmaceuticals. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph4020419

Noori M, Karimi A, Fallah F et al (2014) High prevalence of Metallo beta-lactamase-producing Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from two hospitals of Tehran, Iran. Arch Pediatr Infect Dis. https://doi.org/10.5812/pedinfect.15439

King D, Strynadka N (2011) Crystal structure of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase reveals the molecular basis for antibiotic resistance. Protein Sci. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.697

Poirel L, Jayol A, Nordmanna P (2017) Polymyxins: antibacterial activity, susceptibility testing, and resistance mechanisms encoded by plasmids or chromosomes. Clin Microbiol Rev. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00064-16

Scandorieiro S, de Camargo LC, Lancheros CAC et al (2016) Synergistic and the additive effect of oregano essential oil and biological silver nanoparticles against multidrug-resistant bacterial strains. Front Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00760

Sharifi‐Rad M, Berkay Yılmaz Y, Antika G, Salehi B, Tumer TB, Kulandaisamy Venil C, Das G, Patra JK, Karazhan N, Akram M, Iqbal M (2020) Phytochemical constituents, biological activities, and health-promoting effects of the genus Origanum. Phyther Res

Stojković D, Glamočlija J, Ćirić A et al (2013) Investigation on antibacterial synergism of Origanum vulgare and Thymus vulgaris essential oils. Arch Biol Sci. https://doi.org/10.2298/ABS1302639S

Woodford N, Ellington MJ, Coelho JM et al (2006) Multiplex PCR for genes encoding prevalent OXA carbapenemases in Acinetobacter spp. Int J Antimicrob Agents. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.01.004

Higgins PG, Wisplinghoff H, Krut O, Seifert H (2007) A PCR-based method to differentiate between Acinetobacter baumannii and Acinetobacter genomic species 13TU. Clin Microbiol Infect. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01819.x

Segal H, Garny S, Elisha BG (2005) Is ISABA-1 customized for Acinetobacter? FEMS Microbiol Lett. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.femsle.2005.01.005

Hodge W, Ciak J, Tramont EC (1978) Simple method for detection of penicillinase-producing Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Clin Microbiol 7:102

Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (2015) Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically ; Approved Standard —Tenth Edition. CLSI document M07-A9. Clin Lab Standars Inst. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-237X.91790

Lee K, Lim YS, Yong D et al (2003) Evaluation of the Hodge test and the imipenem-EDTA double-disk synergy test for differentiating metallo-β-lactamase-producing isolates of Pseudomonas spp. and Acinetobacter spp. J Clin Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.41.10.4623-4629.2003

Yong D, Lee K, Yum JH et al (2002) Imipenem-EDTA disk method for differentiation of metallo-β-lactamase-producing clinical isolates of Pseudomonas spp. and Acinetobacter spp. J Clin Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.40.10.3798-3801.2002

Wei W, Yang H (2017) Synergy against extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in vitro by two old antibiotics: colistin and chloramphenicol. Int J Antimicrob Agents. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.11.031

Lescat M, Poirel L, Tinguely C, Nordmann P (2019) A Resazurin Reduction-Based Assay for Rapid Detection of Polymyxin Resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Clin Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01563-18

Hallap T, Nagy S, Jaakma Ü et al (2006) Usefulness of a triple fluorochrome combination Merocyanine 540/Yo-Pro 1/Hoechst 33342 in assessing membrane stability of viable frozen-thawed spermatozoa from Estonian Holstein AI bulls. Theriogenology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2005.07.009

Esterly JS, Richardson CL, Eltoukhy NS et al (2011) Genetic mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii. Ann Pharmacother 45:218

Blair JMA, Webber MA, Baylay AJ et al (2015) Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol 13:42

Prestes-Carneiro LE, Azevedo AM, Nakashima MA et al (2015) Frequency and antimicrobial susceptibility of pathogens at tertiary public hospital, Sao Paulo, Brazil. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 46:276

Sheck EA, Edelstein MV, Sukhorukova MV et al (2017) Epidemiology and genetic diversity of colistin nonsusceptible nosocomial acinetobacter baumannii strains from Russia for 2013–2014. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/1839190

Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB et al (2012) Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x

Kabbaj H, Seffar M, Belefquih B et al (2013) Prevalence of Metallo- β -Lactamases Producing Acinetobacter baumannii in a Moroccan Hospital. ISRN Infect Dis. https://doi.org/10.5402/2013/154921

Paton R, Miles RS, Hood J et al (1993) ARI 1: β-lactamase-mediated imipenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Int J Antimicrob Agents. https://doi.org/10.1016/0924-8579(93)90045-7

Maya JJ, Ruiz SJ, Blanco VM et al (2013) Current status of carbapenemases in Latin America. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 11:657

Labarca JA, Salles MJC, Seas C, Guzmán-Blanco M (2016) Carbapenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii in the nosocomial setting in Latin America. Crit Rev Microbiol 42:276

Turton JF, Ward ME, Woodford N et al (2006) The role of ISAba1 in expression of OXA carbapenemase genes in Acinetobacter baumannii. FEMS Microbiol Lett. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00195.x

Chen TL, Lee YT, Kuo SC et al (2010) Emergence and distribution of plasmids bearing the blaOXA-51- like gene with an upstream ISAba1 in carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates in Taiwan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00764-10

Fournomiti M, Kimbaris A, Mantzourani I et al (2015) Antimicrobial activity of essential oils of cultivated oregano ( Origanum vulgare ), sage ( Salvia officinalis ), and thyme ( Thymus vulgaris ) against clinical isolates of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella oxytoca, and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microb Ecol Heal Dis. https://doi.org/10.3402/mehd.v26.23289

Vasconcelos NG, Croda J, Silva KE et al (2019) Origanum vulgare l Essential oil inhibits the growth of carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0502-2018

Silva JPL, Duarte-Almeida JM, Perez DV, de Franco BDGM (2010) Óleo essencial de orégano: interferência da composição química na atividade frente a Salmonella Enteritidis. Ciência e Tecnol Aliment. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0101-20612010000500021

Rosato A, Piarulli M, Corbo F et al (2010) In vitro synergistic action of certain combinations of gentamicin and essential oils. Curr Med Chem. https://doi.org/10.2174/092986710792231996

Cattelan MG, Nishiyama YPO, Gonçalves TMV, Coelho AR (2018) Combined effects of oregano essential oil and salt on the growth of Escherichia coli in salad dressing. Food Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fm.2018.01.026

Sakkas H, Gousia P, Economou V et al (2016) In vitro antimicrobial activity of five essential oils on multidrug resistant Gram-negative clinical isolates. J Intercult Ethnopharmacol. https://doi.org/10.5455/jice.20160331064446

Jan S, Rashid M, Abd-Allah EF, Ahmad P (2020) Biological efficacy of essential oils and plant extracts of cultivated and wild ecotypes of Origanum vulgare L. Biomed Res Int. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8751718

Rattanachaikunsopon P, Phumkhachorn P (2010) Assessment of factors influencing antimicrobial activity of carvacrol and cymene against Vibrio cholerae in food. J Biosci Bioeng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiosc.2010.06.010

Burt SA, Van Der Zee R, Koets AP et al (2007) Carvacrol induces heat shock protein 60 and inhibits synthesis of flagellin in Escherichia coli O157:H7. Appl Environ Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00340-07

Bnyan I, Hasan H, Ewadh M (2014) Antibacterial activity of carvacrol against different types of bacteria. Adv Life Sci Technol

Valcourt C, Saulnier P, Umerska A et al (2016) Synergistic interactions between doxycycline and terpenic components of essential oils encapsulated within lipid nanocapsules against gram negative bacteria. Int J Pharm. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.11.042

Lambert RJW, Skandamis PN, Coote PJ, Nychas GJE (2001) A study of the minimum inhibitory concentration and mode of action of oregano essential oil, thymol and carvacrol. J Appl Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01428.x

Lira MC, Rodrigues JB, Almeida ETC et al (2020) Efficacy of oregano and rosemary essential oils to affect morphology and membrane functions of noncultivable sessile cells of Salmonella Enteritidis 86 in biofilms formed on stainless steel. J Appl Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.14423

Fernández JL, Cartelle M, Muriel L et al (2008) DNA fragmentation in microorganisms assessed in situ. Appl Environ Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00318-08

Dubnau D (1999) DNA uptake in bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 53:217

Cacciatore I, Di Giulio M, Fornasari E et al (2015) Carvacrol codrugs: a new approach in the antimicrobial plan. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0120937

Sharifi-Rad M, Varoni EM, Iriti M et al (2018) Carvacrol and human health: a comprehensive review. Phyther Res 32:1675

Cleff MB, Meinerz AR, Sallis ES et al (2008) Toxicidade pré-clínica em doses repetidas do óleo essencial do Origanum vulgare L. (Orégano) em ratas Wistar. Lat Am J Pharm 27:704

Acknowledgements

We thank the Laboratory of Microbiology, School Hospital, Federal University of Pelotas (UFPel, Pelotas, RS, Brazil) for their collaboration and providing the isolates.

Funding

This work was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES, http://www.capes.gov.br/) - Finance Code 001 and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, http://www.cnpq.br/) which provided research (DDH) and scholarship (SCA, SBF and SOA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SCA—participated in the experiments, wrote the manuscript; BBP—participated in the experiments MHT, DDST, CDT, MIC e CBM; SOA—participated in the synergism test; SBF, MRAF, and CMJ—participated in the bacteria cultivation, extraction of DNA and PCR; DIBP—wrote the manuscript; ASVJ—flow cytometry; DDH—coordinator, wrote and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This research did not involve humans and animal participants, their data, or biological material. The isolates of A. baumannii used in this research belong to the culture collection of the Laboratory of Bacteriology and Bioassays, collected during the years of 2014 to 2016 in the School Hospital of the Federal University of Pelotas (UFPel, Pelotas, RS, Brazil. This study was approved by the appropriate institution (UFPel, Pelotas, RS, Brazil) under number 10146.

Informed consent

All authors consented to participate in the research. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and agreed to publish the research data.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Amaral, S.C., Pruski, B.B., de Freitas, S.B. et al. Origanum vulgare essential oil: antibacterial activities and synergistic effect with polymyxin B against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Mol Biol Rep 47, 9615–9625 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-020-05989-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-020-05989-0