Abstract

Reducing invasive species abundance near the leading edge of invasions is important for maintaining diverse, high-functioning ecosystems, but it can be hard to remove invasives present at low levels within desirable plant communities. Focusing on an invasive annual grass, Bromus tectorum, near the edge of its range in the southern Colorado Plateau, we used an observational study to ask what plant community components were associated with lower levels of B. tectorum, and a manipulative experiment to ask if targeted spring grazing or seeding native competitors were effective for reversing low-level invasion. The observational study found that higher C3 perennial grass cover and shrub cover were associated with lower B. tectorum abundance, and adult Poa fendleriana and Pascopyrum smithii plants had the fewest B. tectorum individuals within 50 cm. Our manipulative experiment used a randomized, hierarchical design to test the relative effectiveness of seeding native perennial grasses using different spatial planting arrangements, seeding rates, seed enhancements, and targeted spring grazing. Two years after seeding, seeded species establishment was 36% greater in high seed rate than unseeded plots, and high rate plots also had lower B. tectorum cover. One season after targeted spring grazing (a single, 2-week spring-grazing treatment 17 months post-seeding), grazed paddocks displayed trends towards higher seeded species densities and lower B. tectorum biomass in certain seeding treatments, compared to ungrazed paddocks. Results suggest high rate native grass seedings may be effective and short-duration spring grazing should be further evaluated as potential tools for preventing ecosystem conversion along invasion fronts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In many dry shrublands of western North America, plant community composition and structure have been drastically altered by the introduction of invasive annual grasses, including Bromus tectorum L., also called cheatgrass or downy brome. Invasive annual grasses increase fuel loads and fuel continuity, ultimately increasing the likelihood of fire ignition and spread (Balch et al. 2013; Brooks et al. 2004; Davies and Nafus 2013; Pilliod et al. 2017) in ecosystems where wildfires were historically localized or infrequent (Klinger and Brooks 2017). Following fire, cover and density of B. tectorum typically increase (e.g., Kulpa et al. 2012), creating a positive feedback cycle that has caused widespread ecosystem conversions from perennial shrublands to grasslands dominated by non-native annuals across hundreds of thousands of square kilometers in the Western US (Alba et al. 2015; Balch et al. 2013; Bradley et al. 2018; D’Antonio and Vitousek 1992). Broad-scale conversions are most likely after B. tectorum has established a pervasive but low-level presence: in the Great Basin, the probability of fire increases dramatically even at very low (1–5%) levels of B. tectorum cover (Bradley et al. 2018). Thus, a key research and management goal is to determine how to slow or reverse low-level invasions before they lead to ecosystem conversions or expand to new sites.

In order to minimize or reverse low-level invasion, it is important to identify what aspects of uninvaded ecosystems make them resistant to invasion. At broad scales, resistance to B. tectorum is related to temperature and moisture regimes. Colder and higher elevation systems show more resistance (Chambers et al. 2014); however, within the elevational range where it occurs, B. tectorum prevalence tends to be higher at higher elevations (Williamson et al. 2020). Resistance may be further aided by monsoonal (summer-dominated) precipitation patterns that benefit native plants actively growing in the summer months, at the expense of B. tectorum, which typically senesces before monsoonal moisture arrives (Bradley 2009; Brummer et al. 2016). Within climate regimes suitable for B. tectorum, invasion resistance has been primarily related to perennial bunchgrass cover, and to a lesser degree, cover of other native vascular plants and biocrusts, with mechanisms of biotic resistance related to soil resource acquisition (Bansal and Sheley 2016; Beckstead and Augspurger 2004; Brummer et al. 2016; Chambers et al. 2014; Condon et al. 2011; Condon and Pyke 2018; Slate et al. 2019). In the Great Basin, increased gaps between perennial bunchgrasses, increased litter, and soil disturbances have all been associated with B. tectorum invasion (Beckstead and Augspurger 2004; Chambers et al. 2014; Jones et al. 2015; Reisner et al. 2013). Thus, both biotic and abiotic factors can drive invasion resistance at finer spatial scales.

Previous studies have shown that impacts of livestock grazing on B. tectorum invasion and invasion resistance vary based on grazing intensity, timing, and site characteristics. In the Great Basin, legacies of historical heavy livestock grazing have been identified as one factor associated with the widespread invasion of B. tectorum (Williamson et al. 2020; Bradley and Marvin 2011; DiTomaso 2000; Mack 1981). Intense grazing (e.g., use that occurs 100–400 m from watering points) can facilitate B. tectorum invasion by reducing perennial bunchgrass cover, widening gaps between perennial plants, and weakening facilitative interactions between shrubs and perennial grasses (Holthuijzen and Veblen 2016; Reisner et al. 2013). Grazing can also reduce grass seedbanks (Diamond et al. 2012; Schmelzer 2009). At the same time, targeted grazing can be used as a strategy for enhancing invasion resistance in some instances. Targeted grazing is designed to achieve specific vegetation management goals via specified timing, duration, and intensity of use (Frost and Launchbaugh 2003). Targeted grazing can disrupt the grass-fire cycle by reducing fuel loads and connectivity, and increasing fuel moisture (Belsky and Blumenthal 1997; Davies et al. 2016a, 2010, 2016b, 2017, 2009; Diamond et al. 2009; Porensky et al. 2018; Schmelzer 2009), though effects are limited when fire weather becomes extreme (Strand et al. 2014). Targeted spring grazing can also reduce B. tectorum seed production (Diamond et al. 2012).

In the Colorado Plateau region of southwestern North America, substantial B. tectorum invasions can occur despite monsoonal precipitation and the presence of intact summer-active perennial vegetation (e.g., Belnap and Phillips 2001). At broad scales, hotspots of invasion in the Colorado Plateau have been correlated with greater soil water availability, lower elevations, colder mean winter temperatures, flatter slopes, higher soil clay content, and lower mean fall precipitation (Bishop et al. 2019). Intact biological soil crusts reduce suitable microsites for B. tectorum seeds to establish (Belnap et al. 2006; Deines et al. 2007; Serpe et al. 2006, but see Ferrenberg et al. 2018). Intensive grazing and the removal of livestock grazing have both been associated with reduced ecosystem function and more invasion than moderate grazing in this system (Loeser et al. 2007; Munson et al. 2016).

Active restoration approaches (i.e. resource inputs and manipulations of plant communities via seeding, herbicide, targeted grazing, or other methods) may be useful for increasing biotic resistance within lightly-invaded systems (e.g., Munson et al. 2015). However, active restoration may be risky in largely intact arid ecosystems, since many common methods could lead to soil erosion, damage to desired species, further invasion, or other unintended consequences (e.g., Abella and Chiquoine 2019; Diamond et al. 2012; Owen et al. 2011; Pierson et al. 2007; Porensky et al. 2018).

This study evaluated which plant community components were associated with resistance to further B. tectorum invasion along the edge of its invasion front in the Colorado Plateau, and experimentally tested the separate and combined efficacy of five approaches that could be utilized in lightly invaded uplands to increase resistance to additional B. tectorum invasion. Focusing on native seed addition and targeted spring grazing, we tested approaches that may be effective in lightly invaded communities, including: using seed coatings to increase water availability for germinating seeds (Madsen et al. 2012), choosing species that can compete at the seedling stage with invasive annuals (Rowe and Leger 2011), bolstering seeding rates of native species (Mazzola et al. 2010), using spatial separation (i.e. planting species individually rather than as part of a seed mix) to reduce competition among planted species (Porensky et al. 2012; Vaughn and Young 2015), and using targeted spring grazing to reduce invasive plant competition and associated wildfire risk (Davies et al. 2017; Schmelzer et al. 2014). Our research addressed four main questions:

-

A)

Do plant functional groups of northern Arizona differ in their association with B. tectorum abundance?

-

B)

Do adults of different native perennial grass species differ in their association with B. tectorum abundance?

-

C)

What are the best methods for establishing native perennial grasses in these systems?

-

D)

Can seeding or targeted spring grazing treatments affect B. tectorum cover or biomass?

We predicted that native perennial bunchgrasses would be effective at resisting B. tectorum, and that cool-season C3 grasses would have the strongest suppressive effect given their potential for overlapping phenology. We expected strong direct effects of our planting and grazing treatments on the establishment of planted species. Specifically, we predicted that high seed rates, spatial separation, and seed coating techniques would improve the establishment of seeded grasses, and expected targeted spring grazing would have negative impacts on seeded species establishment in the first year after seeding, but positive impacts on seeded species survival due to reductions in competition from B. tectorum. During their first two years of establishment, we expected perennial grass seedlings to have minimal effects on B. tectorum abundance, but predicted that targeted spring grazing would reduce B. tectorum cover, indirectly benefiting seeded species establishment.

Methods

Study site

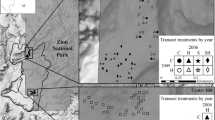

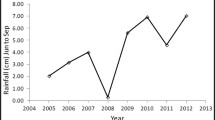

The study site was in the Kaibab National Forest in northern Arizona (Fig. 1a; 36.64–36.57°N, 112.38–112.51°W; 1800–2100 m elevation). Annual precipitation (30-year average) is approximately 406 mm and occurs primarily during the winter/spring and the summer monsoon season. Precipitation was within 10% of the 30-year average for the 2015 and 2016 water years (October–September), with a wetter-than-average (~ 160%) 2015 summer and drier than average (~ 60%) 2016 winter and spring (PRISM Climate Group). Soils are shallow, very stony fine sandy loams derived from Kaibab limestone and sandstone (Soil Survey Staff 2015) and lacked a robust soil biotic crust component. Vegetation was a patchy and diverse mixture of pinyon-juniper woodlands, big sagebrush shrublands, Gambel oak and cliffrose brushlands, and forb-rich grasslands, including both warm-season (C4) and cool-season (C3) grasses. We encountered 135 unique plant taxa, including 17 species of shrubs, 19 grasses, 4 cacti, and over 95 forbs (Appendix A). The majority of species were native (Appendix A); however, non-native, invasive species had increased in abundance following the Bridger Knoll (1996) and Slide (2007) fires, prompting concern that observed increases in B. tectorum abundance were facilitating cheatgrass-fire cycles akin to those of the Great Basin (Sisk et al. 2010).

The experiment had a hierarchical design with three levels. a Blocks and paddock-scale treatments. Each of nine blocks contained two 20.2 ha paddocks randomly assigned to grazing treatments. Each paddock contained eight 0.12 ha planted plots and twelve unseeded control plots. Unseeded plots were randomly interspersed among planted plots (> 15 m from any planted plot). b Plot- and subplot-scale treatments. The eight plots within each paddock were randomly assigned to four different grass restoration treatments. Each planted plot included three 20 × 20 m subplots, one of which was randomly assigned to the coated seed treatment. In monoculture treatments, colors represent different species. Plant cover and seeded species densities were sampled in both red and black quadrats; non-seeded species densities were only sampled in red quadrats

Native grass seeding and targeted spring grazing experiment (Questions A, C and D)

The experimental design paralleled that of a sister targeted grazing and seeding experiment conducted at a highly-invaded Great Basin site (Porensky et al. 2018). At both sites, the experiment was hierarchical with three levels (split-split plot). At the broadest scale, targeted spring grazing treatments were implemented using a randomized complete block design. Eighteen 20.2 ha paddocks were arranged into nine blocks (Fig. 1a). Blocks were randomly located within broader areas that were non-randomly selected to represent plant communities with low tree cover and high B. tectorum cover (average B. tectorum cover in these study blocks was 11% in 2014, and 6 blocks included previously burned areas). For six of the blocks, one paddock per block was randomly assigned a targeted spring grazing treatment. Other blocks remained ungrazed due to unavailability of grazing animals for operational reasons; for these blocks, both paddocks were analyzed as ungrazed (N = 6 grazed and 12 ungrazed paddocks). Targeted spring grazing treatments were implemented 17 months after seeding treatments (described below) to minimize the negative impacts of targeted spring grazing on seeded species establishment. Twenty dry cows grazed each of the six spring-grazed paddocks for two weeks in April, 2016. We estimate that the grazing treatment achieved 30% utilization across grass species, based on (1) the reduction of grass size and weight as determined by ocular estimation and (2) clipping, drying, and weighing aboveground herbaceous biomass in 0.5 × 1 m frames at 9 random locations in each grazed and paired, ungrazed paddock soon after the removal of cows.

Within each paddock (middle level of the hierarchical design), we established eight 20 × 60 m experimental plots separated by ≥ 50 m. These plots were randomly assigned to four native grass seeding treatments, with two replicates of each treatment per paddock. Treatments included all combinations of two spatial arrangement treatments and two seed rate treatments (Fig. 1b). In the monoculture spatial arrangement plots, five native perennial grass species (described below) were seeded separately into adjacent 4-m wide strips within each 20 × 60 m plot. In mixture plots, the same amount of seed per species was used as in monoculture plots, but all seeds were mixed together before planting and seed was distributed across the entirety of each 20 × 60 m plot. Thus, monoculture and mixture plots differed only in the spatial distribution of seed. To avoid disturbance to soil and resident plants and because drill seeding was often infeasible due to very rocky soils, seeds were added using a broadcast seeding method. Plots were broadcast seeded using handheld broadcast seeders (for monoculture plots) or UTV-mounted broadcast seeders (for mixture plots) in November 2014. No rakes or chains were used following broadcast seeding.

At the finest experimental design scale (split-split plot), each experimental grass plot included three 20 × 20 m subplots, one of which was randomly selected for a coated seed treatment. Seeds were coated with a non-ionic alkyl terminated block co-polymer surfactant coating based on C1–C4 alkyl ethers of methyl oxirane–oxirane copolymers (Aquatrols Corporation of America, Paulsboro, NJ). This surfactant has been used to increase the wettability of water‐repellent soils (Fernelius et al. 2017; Kostka 2000) and can also improve plant drought tolerance in wettable soils (Ahmed et al. 2018).

For all seed addition treatments, five perennial grass species were selected from a pool of species native to the region, emphasizing a diversity of life-history strategies. Species included four locally abundant C3 grasses: Elymus elymoides (Raf.) Swezey [squirreltail], Pascopyrum smithii (Rydb.) Á. Löve [western wheatgrass], Poa fendleriana (Steud.) Vasey [muttongrass], Achnatherum hymenoides (Roem. & Schult.) Barkworth [Indian ricegrass], as well as a locally common C4 grass (Sporobolus cryptandrus (Torr.) A. Gray [sand dropseed]). Following NRCS recommendations, seed rates for the low rate treatment were: E. elymoides 6.11 PLS kg/ha; P. smithii 10.65 PLS kg/ha; P. fendleriana 1.3 PLS kg/ha; A. hymenoides 8.31 PLS kg/ha; and S. cryptandrus 0.22 PLS kg/ha; these rates were doubled for the high rate treatment. For a given seed rate, all plots received the same total number of PLS.

Pretreatment vegetation data were collected from eight 20 m transects per paddock in June 2014. These included 4 randomly-located transects within plots designated for seeding treatments, and 4 randomly-located transects in unseeded areas. For 10 evenly-spaced 20 × 50 cm quadrats per transect, we visually estimated aerial plant canopy cover (i.e. plant material that would intercept a raindrop) by species. For portions of the quadrat without plant cover, we estimated cover of litter (detached plant tissue less than 2 cm diameter), wood (woody plant matter larger than 2 cm diameter), rock (larger than 1 cm), moss/biocrust, and bare ground. We also recorded plant density and number of inflorescences by species for all vascular plants in two quadrats per transect.

Post-seeding data were collected in June 2015, and post-seeding and post-targeted spring grazing data were collected in June–July 2016. We recorded species-specific aerial cover and density at multiple sampling stations per seeded plot (Fig. 1b) as well as once at each unseeded plot. We estimated plant cover in 1 × 1 m quadrats using the visual estimation methods described above and recorded seedling densities of all seeded species in the northeast 50 × 50 cm corner of each quadrat frame. Because of small seedling sizes, it was difficult to confidently distinguish among some planted grass species, so seeded species seedling densities and aerial cover of seeded species seedlings were recorded in aggregate. We also recorded density and inflorescence counts by species for all vascular plants in the northeast 25 × 25 cm corner of the frame at two sampling stations per plot (Fig. 1b) and within each unseeded control.

In June 2015 and August 2016, we quantified standing biomass in each paddock by clipping all aboveground non-shrub biomass rooted inside 1 × 1 m and 0.5 × 0.5 m frames, respectively. We sampled at 5 locations per paddock in June 2015 (one randomly selected seeded plot and four unseeded locations), and at 22 locations per paddock (once per seeding treatment plot and at all 12 unseeded locations) in August 2016. Clipping locations were shifted 3 to 10 m each sampling effort to avoid resampling the same areas. Biomass was separated into four categories (B. tectorum, forbs, seedlings of seeded species, and all other native grasses), then oven-dried and weighed.

Species-specific B. tectorum exclusion study (Question B)

We sampled a subset of invaded paddocks to investigate the ability of different perennial grasses to potentially resist B. tectorum invasion. Sampling was conducted in October 2015 within the six paddocks (arranged into three blocks) that had the highest cover and density of B. tectorum. Within each paddock, we sampled along four random 20 m transects in unseeded areas. On both sides of the transect at each of ten evenly spaced points, we selected the nearest adult individual belonging to one of the five native perennial grass species seeded in the manipulative experiment. For each sampled plant, a 20 × 50 cm frame was centered against the edge of the plant base, extending perpendicular to and away from the transect. The frame was divided into three rectangular sampling regions (0–10 cm, 10–20 cm, 20–50 cm), with the 0 cm mark against the sample plant.

For each sample plant, the basal diameter and tallest leaf height were measured. Within each of the three sampling regions, B. tectorum density was recorded, and the cover class (1 = 0–10%, 2 = 10–50%, 3 = 50–100%) of each of five functional groups was visually estimated. Functional groups were: heterospecific grass (all but the species of the focal plant), conspecific grass (including only the species of the focal plant), forb, subshrub, and shrub.

Data analysis

To answer question A, “Do plant functional groups of northern Arizona differ in their association with B. tectorum abundance?”, we used 2014 pretreatment data averaged at the transect scale to produce 8 data points per paddock. We used generalized linear-mixed-models with a model selection and model averaging approach to determine which plant functional groups were most closely associated with B. tectorum cover, density and inflorescence counts at each transect. Predictor variables in a global model included the cover of six different plant functional groups (C3 perennial grasses, C4 perennial grasses, shrubs, cacti, forbs, and non-B. tectorum annual grasses; Appendix A). Block and paddock nested within block were included as random factors. We compared the global model to all possible subsets, including a null (intercept + random effects) model. Using all models within 4 AICc units of the best model, we performed full model averaging to further isolate the most important predictors of B. tectorum abundance. To test whether B. tectorum invasion was associated with litter cover, we regressed pretreatment B. tectorum cover against pretreatment litter cover for each transect, including random factors as described above.

To answer question B, “Do adult native perennial grass species differ in their association with B. tectorum abundance?”, we used data from the species-specific B. tectorum density counts conducted in October 2015. We used generalized linear-mixed-models with a model selection and model averaging approach as described above to determine which predictors were most closely associated with B. tectorum density at different distances from adult native perennial grass individuals. Predictors included species identity of the focal perennial grass, scaled size of the perennial grass (bunchgrass volume/maximum bunchgrass volume measured in the study), and cover class of forbs, heterospecific grasses, conspecific grasses, subshrubs, and shrubs in the same zone as B. tectorum. We calculated bunchgrass volume as π * (bunchgrass diameter/2)2) * (bunchgrass height). Random factors included block, paddock nested within block, and transect nested within both paddock and block.

For question C, “What are the best methods for establishing native perennial grasses in these systems?”, data on seeded species establishment were analyzed using generalized linear-mixed-models with a negative binomial distribution and a log link function due to zero-inflated count data. This distribution fit the data significantly better than other potential distributions (e.g., Gaussian, Poisson, Gamma). We ran two models using seedlings of seeded species per m2 as the response variable. Two models were necessary because it was not possible to evaluate all treatments across all plots. For example, we could not include data from areas we didn’t seed in a model investigating the effect of using coated versus uncoated seeds. For both models, random effects included block, paddock nested within block, and plot nested within paddock and block. The first model (seeding X grazing model) determined if plots planted with native grasses seeded at high or low rates had greater seeded species seedling densities than unseeded controls, and if targeted spring grazing affected seeded species seedling densities. For year one data, collected prior to initiation of targeted spring grazing treatments, the only fixed effect in the model was seeding rate (high rate seeding, low rate seeding, or unseeded). For second-year data, fixed effects included seeding rate, targeted spring grazing treatment, and their interaction.

The second model (planting strategies model) assessed the effects of different planting methods on seeded species densities, using only data from plots seeded with native grasses. Fixed effects included seed rate (high or low), spatial arrangement, seed coating, targeted spring grazing treatment (for second-year data), and all interactions among these factors. Seed coating subplot was added as an additional random effect nested within plot, paddock and block.

To answer question D, “Can native seeding or targeted spring grazing treatments affect B. tectorum cover or biomass?”, we analyzed B. tectorum cover and density data in 2016 using linear mixed-models. Random effects included block, grazing paddock nested within block, and plot nested within paddock and block. Fixed effects included 2015 B. tectorum cover (covariate), targeted spring grazing treatment, seeding rate (unseeded, low rate seeding, high rate seeding), and the interaction of targeted spring grazing treatment and seeding rate. To further explore the impact of seeded species on B. tectorum, we also regressed 2016 B. tectorum cover and density on seeded species seedling densities within each seed rate category (high, low, or unseeded), and B. tectorum cover levels from 2015 were included as a covariate in these regressions.

Finally, we used linear mixed-models to analyze B. tectorum biomass in 2015 and 2016. Each year was analyzed separately due to differences in data collection intensity between years. Fixed effects included targeted spring grazing, seeding rate (unseeded, low rate seeding, high rate seeding), and their interaction. Random factors included block and grazing paddock nested within block. For 2016 data, a negative binomial model structure was used due to non-normality of biomass data.

Analyses were conducted in R 3.4.0 using the lme4 (Bates et al. 2015) and MuMIn (Bartoń 2015) packages, and with JMP (JMP®, Version 12. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 1989–2007). Data were transformed or variance-weighted when necessary to meet model assumptions. All results were considered significant at p < 0.05 and marginally significant at 0.05 < p < 0.10, and are reported as means ± standard error (SE). Means separations were done using Tukey HSD.

Results

Do plant functional groups of northern Arizona differ in their association with B. tectorum abundance?

Using 2014 pretreatment data, we determined that high cover of C3 perennial grasses was associated with significantly lower B. tectorum cover, density, and inflorescence counts. In all cases, the best models based on AICc included C3 perennial grass cover (Table 1), and this parameter was highly significant in all averaged models (Table 2). Across all plots, an increase in C3 perennial grass cover from 0 to 20% was associated with an approximately 50% reduction in B. tectorum cover, density, and inflorescence number (Fig. 2a–c). Bromus tectorum inflorescence counts were also negatively associated with shrub cover (Fig. 2d), though there were no significant associations between shrub cover and B. tectorum density or cover (Tables 1 and 2). No other plant functional groups were significantly associated with B. tectorum abundance metrics. A regression of B. tectorum cover on litter cover indicated that litter was not strongly associated with B. tectorum cover in this system (F1,88 = 1.76, p = 0.18).

Bivariate relationships between C3 grass cover and B. tectorum a cover, b density, and c inflorescence density as well as between d shrub cover and B. tectorum inflorescence density. Graphs display raw values, but models included effects of other plant functional groups on B. tectorum (Table 2) and response variables were log-transformed for analysis

Do adult native perennial grass species differ in their association with B. tectorum abundance?

We found strong associations between adult native perennial grass species identity and B. tectorum density at all measured distances. Overall, P. fendleriana had the greatest suppressive effect on B. tectorum at all distances, and P. smithii had intermediate effects relative to the three other species. In areas 0–10 cm from the focal perennial grass, our best model had an RMSE of 0.7895 and an AICc of 2065.5. Fourteen alternative models were within 4 AICc units of the best model, while the null model AICc was 2088.6. Areas within 10 cm of P. fendleriana bases had 40–60% fewer B. tectorum individuals as areas near A. hymenoides, E. elymoides, or S. cryptandrus bases, while areas adjacent to P. smithii bases had intermediate B. tectorum densities (Fig. 3; Table 3). In the 0–10 cm zone, B. tectorum abundance was lower in microsites with higher conspecific grass cover and larger focal bunchgrasses (Table 3).

Impacts of adult perennial grass species identity on B. tectorum abundance within 50 cm. Species identity was associated with B. tectorum densities in all three distance zones. Within each distance zone, species sharing letters were not significantly different. Bars display raw means, but models assumed a negative binomial distribution and included effects of other factors on B. tectorum densities (Table 3). Species codes: ACHY Achnatherum hymenoides; ELEL Elymus elymoides; PASM Pascopyrum smithii; POFE Poa fendlariana; SPCR Sporobolus cryptandrus

In the area 10–20 cm away from the focal perennial grass, our best model had an RMSE of 0.7935 and an AICc of 2177.3. 31 alternative models were within 4 AICc units of the best model, while the null model AICc was 2208.1. P. fendleriana and P. smithii had 25–50% fewer B. tectorum individuals than S. cryptandrus, and P. fendleriana had about 60% fewer B. tectorum individuals than A. hymenoides or E. elymoides (Fig. 3).

In areas 20–50 cm away from the focal perennial grass, our best model had an RMSE of 0.8548 and an AICc of 3022.2. 15 alternative models were within 4 AICc units of the best model, while the null model AICc was 3051.9. Areas 20–50 cm from P. fendleriana or P. smithii bases continued to have significantly fewer B. tectorum individuals than areas 20–50 cm from S. cryptandrus (Fig. 3). At this distance, microsites with more forb cover had significantly more B. tectorum individuals, but cover of other functional groups was not significantly associated with B. tectorum density (Table 3).

What are the best methods for establishing native perennial grasses in these systems?

2015 results In June 2015, one growing season after sowing, densities of seeded native grass species were very low and were not significantly affected by any of our experimental treatments, including seeding treatments (p-values > 0.10).

2016 results Across analyses, data from 2016 revealed that higher seeding rates increased the density of seeded species. Effects of targeted spring grazing were weaker, but apparent in certain seed rate or planting treatments. Specifically, the seeding X grazing model revealed a main effect of seeding rate on seeded species density in 2016: grass plots planted at a high seed rate had 36% more seedlings of seeded species than unseeded plots, while low seed rate grass plots had intermediate seedling densities that were not significantly different from other treatments (Fig. 4a; F2,337 = 3.84, p = 0.02). Targeted spring grazing and the interaction of targeted spring grazing with seed rate did not significantly influence seeded species seedling abundance at this scale of the experiment (p-values > 0.4; values are shown for both grazed and ungrazed treatments in Fig. 4a).

Impacts of a seed rate, b seed coating, and c interactions among grazing, seed rate and spatial arrangement on density of seedlings of planted grass species in 2016. Bars display raw means, but models assumed a negative binomial distribution and included effects of other factors on seedling densities. Values are shown for both grazed and ungrazed treatments in panel a, though the interaction between density and grazing was not significant (see results). In panel b, data from unseeded plots are shown for comparison, but statistical results are from the ‘planting strategies’ model which included only seeded plots. Seed rates (in panel a) or coating treatments (in panel b) sharing letters were not significantly different

The planting strategies model (comparing among different types of seeded grass plots) revealed that seed coating was associated with a 14% reduction in 2016 seeded species seedling density (Fig. 4b; F1,136 = 4.63, p = 0.03). This model also showed that targeted spring grazing tended to be associated with a 45–78% increase in densities of planted grass species, but only in monoculture plots and high rate mixture plots (Fig. 4c; grazing * seed rate * spatial arrangement F1,120 = 3.62, p = 0.059). No other main effects or interactions affected seeded species seedling densities in the planting strategies model (p-values > 0.14).

Can native seeding or targeted spring grazing treatments affect B. tectorum cover or biomass?

In 2015, biomass of B. tectorum did not differ significantly by seed rate treatments or planned grazing treatments (p-values > 0.13). In 2016, after targeted spring grazing treatments were implemented, B. tectorum biomass in low seeding rate, ungrazed plots tended to be 3 times as high as biomass in other treatment combinations (Fig. 5a; seed rate * grazing F2,247 = 2.90, p = 0.057).

Impacts of planted grass seedlings on B. tectorum a biomass and b cover in 2016. Bars display raw means, but the biomass model assumed a negative binomial distribution and the cover model was run on log-transformed cover data. In panel b, seed rates sharing letters were not significantly different. Values are shown for grazed and ungrazed treatments in panel b, though the interaction between seeding rate and grazing was not significant (see results)

In 2016, B. tectorum cover was significantly affected by seed rate. Plots seeded at high rates had about half as much B. tectorum cover as low rate plots, while unseeded plots had intermediate cover values that were not significantly different from other treatments (Fig. 5b; F2, 162 = 3.24, p = 0.04). Regression analyses supported a significant, negative relationship between seeded species seedling density and B. tectorum cover for high seed rate plots in 2016 (F1,346 = 4.8, p = 0.03), while there was no significant relationship between seedlings and B. tectorum cover for low seed rate or unseeded plots (p-values > 0.4). In high seed rate plots, our regression model predicted that an increase from zero to 25 seedlings per m2 would be associated with a 50% reduction in B. tectorum cover. Targeted spring grazing and the interaction between grazing and seed rate did not significantly influence B. tectorum cover in 2016 (p-values > 0.3; Fig. 5b).

Discussion

The invasion of B. tectorum in the western United States has reduced wildlife habitat, livestock forage, soil health, plant genetic diversity, and other ecosystem values and services in large areas of the Intermountain West (DiTomaso 2000; Eiswerth et al. 2005; Mack 1981). As a result, a large body of literature has explored B. tectorum invasibility in this region (e.g., Bradley et al. 2018; Bradley and Mustard 2006; Brummer et al. 2016; Chambers et al. 2014; Chambers et al. 2007). However, relatively little research has focused on strategies to reduce low-level invasions before full ecosystem conversion occurs in systems near the edge of B. tectorum’s range. In northern Arizona, we found that biotic resistance to B. tectorum invasion is both functional group-specific and species-specific. Although enhancing resistance can be challenging in largely uninvaded systems (e.g., Abella and Chiquoine 2019; Pierson et al. 2007), our results indicate that high-rate broadcast seeding can produce native perennial grass seedlings that quickly begin suppressing B. tectorum abundance in these systems. A targeted two-week spring grazing treatment of 30% utilization (20 animals across 20.2 ha; 13.9 AU Days per ha) did not negatively affect measured outcomes and had several potentially positive, but uncertain outcomes, including increased seedling densities in planted plots and decreased B. tectorum biomass in low seeding rate treatments.

Mechanisms of B. tectorum resistance

Previous work on biotic resistance to B. tectorum invasion has identified native perennial bunchgrass cover as a key driver of resistance (Bansal and Sheley 2016; Beckstead and Augspurger 2004; Brummer et al. 2016; Chambers et al. 2014; Condon and Pyke 2018). Our observational work from the southern edge of the B. tectorum range provided additional evidence supporting the importance of native perennial grasses while also adding important nuance to this body of knowledge. First, we found that C3 (cool-season) perennial grass cover displayed strong, negative associations with all B. tectorum abundance metrics, regardless of growth form (bunchgrass versus rhizomatous grass), while the same was not true for C4 (warm-season) perennial grasses. A likely mechanism is greater overlap in timing of soil resource use between C3 grasses and B. tectorum, a factor which has been shown to reduce B. tectorum cover and biomass (e.g. Borman et al. 1991). Since warm-season grasses and B. tectorum are utilizing resources such as water and soil nutrients during different seasons, it is reasonable to hypothesize that direct competition between them is weak, as we predicted. We also observed that shrub cover was associated with reduced B. tectorum inflorescence production in this system, which is contrary to the facilitative shrub nurse plant effect often observed in the Great Basin (e.g., Griffith 2010). Differences in shrub-B. tectorum interactions may be due to differences in the relative need for amelioration from environmental stresses in these two systems (Bertness and Callaway 1994; Maestre et al. 2009); our site in the Colorado Plateau receives substantially more precipitation than many parts of the Great Basin, and thus interactions between shrubs and understory species may have been more competitive than in more xeric systems (e.g. Callaway et al. 1996). Unlike the Great Basin, where litter enhances B. tectorum seedling establishment by creating safe sites for establishment (Evans and Young 1970; Jones et al. 2015), we did not see a strong relationship between litter and B. tectorum cover in our study. It may be that the level of litter cover observed in our system during the study period was below the level needed to have an appreciable effect on plant dynamics.

Finally, our observational study highlighted the importance of species identity in driving resistance, with P. fendleriana and P. smithii showing the greatest suppressive effects. Our experiment didn’t test mechanisms behind these suppressive effects, but results are consistent with other studies observing similar patterns. For example, research in the Great Basin has also found Poa species to be better at suppressing B. tectorum than either E. elymoides or A. hymendoides, possibly due to early phenology and high root investment (Goergen et al. 2011), and P. smithii is better at suppressing weed communities than A. hymenoides (Porensky et al. 2014). Thus, some genus- or species-level effects may transcend ecosystems. We found no other research on the competitive ability of P. fendleriana, but our results suggest this species may be a good candidate for further study in climate-suitable areas where B. tectorum suppression is desired.

Strategies for enhancing resistance

In addition to exploring patterns of resistance in unmanipulated systems, we also explored the efficacy of five strategies for enhancing resistance in lightly invaded systems by quantifying reductions in B. tectorum establishment under different management strategies. These were: bolstering native seed rates (Mazzola et al. 2010), using seed coatings to increase water availability (Madsen et al. 2012), using spatial separation to reduce competition among planted species (Porensky et al. 2012; Vaughn and Young 2015), using targeted spring grazing to reduce invasive plant competition and associated wildfire risk (Davies et al. 2017; Schmelzer et al. 2014), and planting native species that can compete at the seedling stage with invasive annuals (Rowe and Leger 2011). Of these treatments, bolstering seed rates had the strongest effects, in line with previous work on the importance of propagule pressure as a driver of restoration outcomes (Mazzola et al. 2010; Schantz et al. 2016; Seabloom et al. 2003; St. Clair and Bishop 2019). While seeding into lightly invaded communities may seem unnecessary (presumably, existing species are creating seed rain of their own), research demonstrates that many systems are in fact seed-limited (e.g., Turnbull et al. 2000), and, as we observed in our study, seed addition has been shown to increase plant densities in many systems. However, even with high seed rates, establishment rates remained fairly low: compared to unseeded plots, high seed rate plots had about 2 additional seedlings/m2. Despite these relatively low rates of establishment, and contrary to our hypothesis that planted seedlings might be too young to affect B. tectorum, we found that high seed rate plots had lower B. tectorum cover in 2016. The fact that a negative relationship between seedling abundance and B. tectorum cover was present for high rate plots but not low rate or unseeded plots is consistent with other results demonstrating that even young C3 grasses can have suppressive effects on B. tectorum, likely due to resource competition (Mangla et al. 2011; Rowe and Leger 2011).

Seed coating has been shown to improve seedling establishment in some dryland systems (Madsen et al. 2016a, 2014). However, we observed a slight negative effect of surfactant seed coating on seedling establishment in 2016. It is possible that coated seeds were more attractive to granivores than uncoated seeds in the context of a broadcast seeding treatment. Although the surfactant seed coating technology did not improve seedling establishment, it is still possible that seed coating could improve survival to adulthood for seedlings that did manage to establish. The surfactant coating applied to seeds in our study improved seedling survival under drought stress in previous studies, although in these studies coated seed was planted below the soil, rather than broadcast (Madsen et al. 2016b, 2012, 2014; Porensky et al. 2018). Future research is needed to develop seed coating technologies that will improve broadcast seeding efforts.

The impacts of livestock grazing on B. tectorum invasion are variable, with both intensive grazing and no grazing associated with greater invasion than moderate grazing in the Colorado Plateau (Loeser et al. 2007; Munson et al. 2016). In other systems, targeted grazing has been shown to reduce annual grass seed production (Diamond et al. 2012), and disrupt invasion-fire feedback cycles (Davies et al. 2016a, 2010, 2016b, 2017, 2009; Diamond et al. 2009; Schmelzer et al. 2014). In this study, targeted spring grazing (2 weeks of use, 30% utilization) had marginally significant positive effects on seedling establishment (Fig. 4c) and negative effects on B. tectorum abundance (Fig. 5). In both cases, effect magnitudes were large, but p-values ranged from 0.05 to 0.06, possibly due to low sample size. These results contrast sharply from findings in a more highly invaded Great Basin system, where targeted spring and fall grazing tended to have negative effects on first- and second-year perennial grass seedling densities (Porensky et al. 2018), possibly because little or no alternate forage was available. However, in the lightly invaded Colorado Plateau ecosystem, the presence of established perennial grasses and B. tectorum in the spring likely shifted grazing preference away from smaller seedlings. Thus, grazing may have created space and resources for broadcast seedlings, while simultaneously imposing direct negative effects on B. tectorum. Targeted spring grazing shows promise and should be evaluated at additional sites and across a wider range of weather conditions as a potential tool for lightly invaded sites in the Colorado Plateau, particularly in areas that lack grazing-sensitive biocrusts.

Management implications

Our results suggest that broadcast seeding of highly-suppressive native C3 perennial species (particularly Poa fendleriana and Pascopyrum smithii) at substantially higher-than-typical rates can improve site resistance during the early stages of invasion. We used commercially-available seed sources for this experiment, but managers may consider the use of local ecotypes to maintain historic gene pools in these communities. Broadcast seeding may allow managers to target locations where drill seeding is not possible or where soil disturbance associated with drill seeding is undesirable. The high seed rates required to increase perennial grass seedling establishment may preclude seeding across large areas; instead, managers could focus seeding efforts in strategic locations to combat invasion hotspots or manage fuel characteristics (Gray and Dickson 2015; Hulvey et al. 2017; Porensky et al. 2018). Our results suggest that this approach can help build resistance in those areas and may reduce the ability of B. tectorum to invade new areas. This represents a significant shift in strategy as most seeding efforts are currently directed towards broad-scale rehabilitation after areas become highly invaded. Finally, we note that targeted grazing may facilitate establishment of native perennial grasses, but emphasize that the results presented here are the product of a short, targeted grazing period designed to minimize negative impacts of grazing on desired plant species. This type of short-duration early spring grazing is currently unprecedented in typical, at-scale grazing management strategies of the region. For most managers, implementation of targeted spring grazing would require substantial investments in infrastructure and labor.

Conclusions

To reduce annual grass invasion along invasion fronts in western North America, researchers and managers need more information about how to decrease ecosystem susceptibility. Our work clarifies that specific native plants are associated with lower B. tectorum abundance in the southwestern Colorado Plateau. Using high seed rates, it is possible to get greater numbers of these plants into the system, even if the species are already present. Based on a single season of sampling directly after our targeted spring-grazing treatment, we identified no negative and two potentially positive effects of targeted spring-grazing on desired outcomes. Future sampling will be necessary to evaluate the longer-term effects of this treatment. Additional exploration into the combined effects of seed addition and targeted spring grazing across both wet and dry years could yield valuable, management-relevant knowledge about this highly variable semi-arid system. In biodiverse, lightly invaded regions like the Kaibab Plateau, strategic investment in high rate seedings may be worthwhile if they help prevent broad-scale ecosystem conversion and concomitant loss of biodiversity, wildlife habitat, and forage for valuable wild and domestic animals.

References

Abella SR, Chiquoine LP (2019) The good with the bad: when ecological restoration facilitates native and non-native species. Restor Ecol 27:343–351

Ahmed MA et al (2018) Engineering rhizosphere hydraulics: Pathways to improve plant adaptation to drought. Vadose Zone J 17:160090

Alba C, Skalova H, McGregor KF et al (2015) Native and exotic plant species respond differently to wildfire and prescribed fire as revealed by meta-analysis. J Veg Sci 26:102–113

Balch JK, Bradley BA, D’Antonio CM et al (2013) Introduced annual grass increases regional fire activity across the arid western USA (1980–2009). Glob Change Biol 19:173–183

Bansal S, Sheley RL (2016) Annual grass invasion in sagebrush steppe: the relative importance of climate, soil properties and biotic interactions. Oecologia 181:543–557

Bartoń K (2015) MuMIn. R package version 1.13.4

Bates D et al (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using ime4. J Stat Softw 67:1–48

Beckstead J, Augspurger CK (2004) An experimental test of resistance to cheatgrass invasion: limiting resources at different life stages. Biol Invasions 6:417–432

Belnap J, Phillips S, Troxler T (2006) Soil lichen and moss cover and species richness can be highly dynamic: the effects of invasion by the annual exotic grass Bromus tectorum, precipitation, and temperature on biological soil crusts in SE Utah. Appl Soil Ecol 32:63–76

Belnap J, Phillips SL (2001) Soil biota in an ungrazed grassland: response to annual grass (Bromus tectorum) invasion. Ecol Appl 11:1261–1275

Belsky AJ, Blumenthal DM (1997) Effects of livestock grazing on stand dynamics and soils in upland forests of the interior west. Conserv Biol 11:315–327

Bertness MD, Callaway R (1994) Positive interactions in communities. Trends Ecol Evol 9:191–193

Bishop TBB, Munson S, Gill RA et al (2019) Spatiotemporal patterns of cheatgrass invasion in Colorado Plateau National Parks. Landsc Ecol 34:925–941

Borman MM, Krueger WC, Johnson DE (1991) Effects of established perennial grasses on yields of associated annual weeds. Rangel Ecol Manag 44:318–322

Bradley BA (2009) Regional analysis of the impacts of climate change on cheatgrass invasion shows potential risk and opportunity. Glob Change Biol 15:196–208

Bradley BA, Curtis CA, Fusco EJ et al (2018) Cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) distribution in the intermountain Western United States and its relationship to fire frequency, seasonality, and ignitions. Biol Invasions 20:1493–1506

Bradley BA, Marvin DC (2011) Using expert knowledge to satisfy data needs: mapping invasive plant distributions in the western United States. West N Am Nat 71:302–315

Bradley BA, Mustard JF (2006) Characterizing the landscape dynamics of an invasive plant and risk of invasion using remote sensing. Ecol Appl 16:1132–1147

Brooks ML, D’Antonio CM, Richardson DM et al (2004) Effects of invasive alien plants on fire regimes. Bioscience 54:677–688

Brummer TJ, Taylor KT, Rotella J et al (2016) Drivers of Bromus tectorum abundance in the western North American sagebrush steppe. Ecosystems 19:986–1000

Callaway RM, DeLucia EH, Moore D et al (1996) Competition and facilitation: contrasting effects of Artemisia tridentata on desert vs. montane pines. Ecology 77:2130–2141

Chambers JC, Bradley BA, Brown CS et al (2014) Resilience to stress and disturbance, and resistance to Bromus tectorum L. invasion in cold desert shrublands of western North America. Ecosystems 17:360–375

Chambers JC, Roundy BA, Blank RR et al (2007) What makes great basin sagebrush ecosystems invasible by Bromus tectorum? Ecol Monogr 77:117–145

Condon L, Weisberg PJ, Chambers JC (2011) Abiotic and biotic influences on Bromus tectorum invasion and Artemisia tridentata recovery after fire. Int J Wildland Fire 20:597–604

Condon LA, Pyke DA (2018) Fire and grazing influence site resistance to Bromus tectorum through their effects on shrub, bunchgrass and biocrust communities in the Great Basin (USA). Ecosystems 21:1416–1431

D’Antonio CM, Vitousek PM (1992) Biological invasions by exotic grasses, the grass/fire cycle, and global change. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 23:63–87

Davies KW, Nafus AM (2013) Exotic annual grass invasion alters fuel amounts, continuity and moisture content. Int J Wildland Fire 22:353–358

Davies KW, Svejcar TJ, Bates JD (2009) Interaction of historical and nonhistorical disturbances maintains native plant communities. Ecol Appl 19:1536–1545

Davies KW, Bates JD, Svejcar TJ et al (2010) Effects of long-term livestock grazing on fuel characteristics in rangelands: an example from the sagebrush steppe. Rangel Ecol Manag 63:662–669

Davies KW, Bates JD, Boyd CS et al (2016) Prefire grazing by cattle increases postfire resistance to exotic annual grass (Bromus tectorum) invasion and dominance for decades. Ecol Evol 6:3356–3366

Davies KW, Boyd CS, Bates JD et al (2016) Winter grazing can reduce wildfire size, intensity and behaviour in a shrub-grassland. Int J Wildland Fire 25:191–199

Davies KW, Gearhart A, Boyd CS et al (2017) Fall and spring grazing influence fire ignitability and initial spread in shrub steppe communities. Int J Wildland Fire 26:485–490

Deines L, Rosentreter R, Eldridge D et al (2007) Germination and seedling establishment of two annual grasses on lichen-dominated biological soil crusts. Plant Soil 295:23–35

Diamond JM, Call CA, Devoe N (2009) Effects of targeted cattle grazing on fire behavior of cheatgrass-dominated rangeland in the northern Great Basin, USA. Int J Wildland Fire 18:944–950

Diamond JM, Call CA, Devoe N (2012) Effects of targeted grazing and prescribed burning on community and seed dynamics of a downy brome (Bromus tectorum) dominated landscape. Invasive Plant Sci Manag 5:259–269

DiTomaso JM (2000) Invasive weeds in rangelands: species, impacts, and management. Weed Sci 48:255–265

Eiswerth ME, Darden TD, Johnson WS et al (2005) Input-output modeling, outdoor recreation, and the economic impacts of weeds. Weed Sci 53:130–137

Evans RA, Young JA (1970) Plant litter and establishment of alien annual weed species in rangeland communities. Weed Sci 18:697–703

Fernelius KJ et al (2017) Post-fire interactions between soil water repellency, islands of fertility and Bromus tectorum invasibility. J Arid Environ 144:98–109

Ferrenberg S, Faist AM, Howell A et al (2018) Biocrusts enhance soil fertility and Bromus tectorum growth, and interact with warming to influence germination. Plant Soil 429:77–90

Frost R, Launchbaugh K (2003) Prescription grazing for rangeland weed management: a new look at an old tool. Rangelands 25:43–47

Goergen EM, Leger EA, Espeland EK (2011) Native perennial grasses show evolutionary response to Bromus tectorum (cheatgrass) invasion. PLoS ONE 6:e18145

Gray ME, Dickson BG (2015) A new model of landscape-scale fire connectivity applied to resource and fire management in the Sonoran Desert. USA Ecol Appl 25:1099–1113

Griffith AB (2010) Positive effects of native shrubs on Bromus tectorum demography. Ecology 91:141–154

Holthuijzen MF, Veblen KE (2016) Grazing effects on precipitation-driven associations between sagebrush and perennial grasses. West N Am Nat 76:313–325

Hulvey KB, Leger EA, Porensky LM et al (2017) Restoration islands: a tool for efficiently restoring dryland ecosystems? Restor Ecol 25:S124–S134

Jones RO, Chambers JC, Board DI et al (2015) The role of resource limitation in restoration of sagebrush ecosystems dominated by cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum). Ecosphere 6:1–21

Klinger R, Brooks M (2017) Alternative pathways to landscape transformation: invasive grasses, burn severity and fire frequency in arid ecosystems. J Ecol 105:1521–1533

Kostka SJ (2000) Amelioration of water repellency in highly managed soils and the enhancement of turfgrass performance through the systematic application of surfactants. J Hydrol 231–232:359–368

Kulpa SM, Leger EA, Espeland EK et al (2012) Postfire seeding and plant community recovery in the Great Basin. Rangel Ecol Manag 65:171–181

Loeser MRR, Sisk TD, Crews TE (2007) Impact of grazing intensity during drought in an Arizona grassland. Conserv Biol 21:87–97

Mack RN (1981) Invasion of Bromus tectorum L. into Western North America: an ecological chronicle. Agro-Ecosystems 7:145–165

Madsen MD, Davies KW, Boyd CS et al (2016) Emerging seed enhancement technologies for overcoming barriers to restoration. Restor Ecol 24:S77–S84

Madsen MD, Kostka SJ, Fidanza MA et al (2016) Low-dose application of non-ionic alkyl terminated block copolymer surfactant enhances turfgrass seed germination and plant growth. HortTechnology 26:379–385

Madsen MD, Kostka SJ, Inouye AL et al (2012) Postfire restoration of soil hydrology and wildland vegetation using surfactant seed coating technology. Rangel Ecol Manag 65:253–259

Madsen MD, Zvirzdin DL, Roundy BA et al (2014) Improving reseeding success after catastrophic wildfire with surfactant seed coating technology. Am Soc Test Mater STP 1569:44–55

Maestre FT, Callaway RM, Valladares F et al (2009) Refining the stress-gradient hypothesis for competition and facilitation in plant communities. J Ecol 97:199–205

Mangla S, Sheley RL, James JJ et al (2011) Intra and interspecific competition among invasive and native species during early stages of plant growth. Plant Ecol 212:531–542

Mazzola MB, Chambers JC, Blank RR et al (2010) Effects of resource availability and propagule supply on native species recruitment in sagebrush ecosystems invaded by Bromus tectorum. Biol Invasions 13:513–526

Munson SM, Duniway MC, Johanson JK (2016) Rangeland monitoring reveals long-term plant responses to precipitation and grazing at the landscape scale. Rangel Ecol Manag 69:76–83

Munson SM, Long AL, Decker C et al (2015) Repeated landscape-scale treatments following fire suppress a non-native annual grass and promote recovery of native perennial vegetation. Biol Invasions 17:1915–1926

Owen SM, Sieg CH, Gehring CA (2011) Rehabilitating downy brome (Bromus tectorum)-invaded scrublands using imazapic and seeding with native shrubs. Invasive Plant Sci Manag 4:223–233

Pierson FB, Blackburn WH, Van Vactor SS (2007) Hydrologic impacts of mechanical seeding treatments on sagebrush rangelands. Rangel Ecol Manag 60:666–674

Pilliod DS, Welty JL, Arkle RS (2017) Refining the cheatgrass–fire cycle in the Great Basin: precipitation timing and fine fuel composition predict wildfire trends. Ecol Evol 7:8126–8151

Porensky LM, Leger EA, Davison J et al (2014) Arid old-field restoration: native perennial grasses suppress weeds and erosion, but also suppress native shrubs. Agr Ecosyst Environ 184:135–144

Porensky LM, Perryman BL, Williamson MA et al (2018) Combining active restoration and targeted grazing to establish native plants and reduce fuel loads in invaded ecosystems. Ecol Evol 8:12533–12546

Porensky LM, Vaughn KJ, Young TP (2012) Can initial intraspecific spatial aggregation increase multi-year coexistence by creating temporal priority? Ecol Appl 22:927–936

PRISM Climate Group Oregon State University. https://prism.oregonstate.edu. Assessed 4 Feb 2004

Reisner MD, Grace JB, Pyke DA et al (2013) Conditions favouring Bromus tectorum dominance of endangered sagebrush steppe ecosystems. J Appl Ecol 50:1039–1049

Rowe CLJ, Leger EA (2011) Competitive seedlings and inherited traits: a test of rapid evolution of Elymus multisetus (big squirreltail) in response to cheatgrass invasion. Evol Appl 4:485–498

Schantz MC, Sheley RL, James JJ et al (2016) Role of dispersal timing and frequency in annual grass—invaded Great Basin ecosystems: how modifying seeding strategies increases restoration success. West N Am Nat 76:36–52

Schmelzer L (2009) Reducing fuel load of key cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum L.) dominated range sites by the use of fall cattle grazing. MS Thesis. University of Nevada, Reno

Schmelzer L, Perryman B, Bruce B et al (2014) Case study: reducing cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum L.) fuel loads using fall cattle grazing. Prof Anim Sci 30:270–278

Seabloom EW, Harpole WS, Reichman OJ et al (2003) Invasion, competitive dominance, and resource use by exotic and native California grassland species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:13384–13389

Serpe M, Orm J, Barkes T et al (2006) Germination and seed water status of four grasses on moss-dominated biological soil crusts from arid lands. Plant Ecol 185:163–178

Sisk TD, Albano CM, Aumack EA, Bernstein EJ, Crews TE, Dickson BG, Schlosberg D (2010). Integrating restoration and conservation objectives at the landscape scale: the Kane and Two-mile Ranch project. In: The Colorado Plateau IV: shaping conservation through science and management. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, pp 45–66

Slate ML, Callaway RM, Pearson DE (2019) Life in interstitial space: Biocrusts inhibit exotic but not native plant establishment in semi-arid grasslands. J Ecol 107:1317–1327

Soil Survey Staff NRCS, USDA (2015) Soil survey geographic (SSURGO) database. https://sdmdataaccess.nrcs.usda.gov/

St. Clair SB, Bishop TBB (2019) Loss of biotic resistance and high propagule pressure promote invasive grass-fire cycles. J Ecol 107:1995–2005

Strand EK, Launchbaugh KL, Limb R et al (2014) Livestock grazing effects on fuel loads for wildland fire in sagebrush dominated ecosystems. J Rangel Appl 1:35–57

Turnbull LA, Crawley MJ, Rees M (2000) Are plant populations seed-limited? A review of seed sowing experiments. Oikos 88:225–238

Vaughn KJ, Young TP (2015) Short-term priority over exotic annuals increases the initial density and longer-term cover of native perennial grasses. Ecol Appl 25:791–799

Williamson MA, Fleishman E, Mac Nally RC et al (2020) Fire, livestock grazing, topography, and precipitation affect occurrence and prevalence of cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) in the central Great Basin. USA Biol Inv 22:663–680

Acknowledgements

We thank Justun Jones and Plateau Ranches, and the North Kaibab Ranger District of the Kaibab National Forest for providing facilities, labor, livestock, permission, and in-kind support for this research. For field and data assistance, we are grateful to Marenna Disbro, Quinn Campbell, Eleni Nicholson, Sage Ellis, Jason Sprott, Erick Larsen, Jen Peterson, Amy Prince, and Brian Von Seggern. We are thankful to over 30 volunteers who assisted with planting and data collection. Funding was from a National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture award within the Western Integrated Pest Management program (2013‐34103‐21325), and additional funding was provided by the Arizona Game and Fish Department, and the Grand Canyon Trust.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Porensky, L.M., Baughman, O., Williamson, M.A. et al. Using native grass seeding and targeted spring grazing to reduce low-level Bromus tectorum invasion on the Colorado Plateau. Biol Invasions 23, 705–722 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-020-02397-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-020-02397-0