Abstract

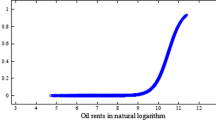

This study makes a substantial contribution to the resources curse argument debates by answering the question of which scenario is bad for the economy “oil abundance” or “oil dependence” by supposing the nonlinearity in this issue. To answer this puzzling question, we use the panel smooth transition regression model (PSTR) for a sample of 33 economies categorized into two sub-panels the oil-abundant economies and the oil-dependent ones for the spanning time from 1990 to 2016. By confirming the nonlinearity in the oil curse argument, our empirical highlights pointed out that the oil curse thesis is very well verified. We revealed that the impact of oil abundance on income factor is more explicit in the oil-abundant economies than in the oil-dependent ones. The estimation of the threshold variable implies that the oil-growth nexus is smoothly switched from one regime to another regime but approximately rapid for the two scenarios. Due to the significant repercussions of the oil on the economic sphere, with the increase of the pace of the climate change symptoms and the depletion of the resources, these economies should seriously take into consideration the resource depletion and the climate emergency issues to preserve the planet’s reserves for future generations towards sustainable and viable future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Saudi Arabia, Russia, Iran, China, Mexico, United Arab Emirates, Venezuela, Norway, Kuwait, Nigeria, Brazil, Algeria, Mexico, Libya, Iraq, Angola, Kazakhstan, Qatar, USA, Japan, Germany, India, Canada, South Korea, France, Great Britain, Italy, Spain, Netherlands, Singapore, Turkey, Thailand, and Belgium

These extreme values are associated with regression coefficients \( {\beta}_0^{\hbox{'}} \) and (\( {\beta}_0^{\hbox{'}}+{\beta}_1^{\hbox{'}} \)).

The impact of the oil abundance on growth is detected by \( {\beta}_0^{\hbox{'}} \) for those economies ifqit ≤ cj and by \( {\beta}_0^{\hbox{'}}+{\beta}_1^{\hbox{'}} \) for those countries where qit > cj.

The selection of the variables, countries, and the starting period was constrained by the resources curse theory and the availability of data.

The oil abundance scenario: (Producer countries + exporting countries):

Producer countries: Saudi Arabia, Russia, Iran, China, Mexico, Canada, United Arab Emirates, Venezuela, Norway, Kuwait, Nigeria, Brazil, Algeria, USA, and Iraq

Exporting countries: Saudi Arabia, Russia, United Arab Emirates, Norway, Iran, Kuwait, Venezuela, Nigeria, Algeria, Mexico, Libya, Iraq, Angola, Kazakhstan, and Qatar

The oil dependence scenario: (Consumer countries + importing countries)

Consumer countries: USA, China, Japan, Russia, Germany, India, Canada, Brazil, South Korea, Mexico, France, Great Britain, and Italy

Importing countries: USA, Japan, China, Germany, South Korea, France, India, Italy, Spain, Netherlands, Singapore, Turkey, Thailand, and Belgium

The oil rent (oil rent expressed as a share of GDP) is multiplied by GDP and divided by the population to determine the aggregate per capita (e.g., Paul [40]).

Following the contribution of [54,55,56,57,58]) and Tiba [50,51,52,53], we use a modified version of the HDI which the does not include the income factor to overcome the multicollinearity issue in the regression analysis. Then the HF formula takes the following form::

HF = \( \frac{1}{2} \)( Gross enrolment+ Life expectancy).

References

Abadie, A., Diamond, A., & Hainmueller, J. (2010). Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: Estimating the effect of California's tobacco control program. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 105, 493–505.

Abou-Ali, H., & Abdelfattah, Y. M. (2013). Integrated paradigm for sustainable development: A panel data study. Economic Modelling, 30, 334–342.

Al-Kasim, F., Soreide, T., & Williams, A. (2013). Corruption and reduced oil production: An additional resource curse factor? Energy Policy, 54, 137–147.

Apergis, N., & Payne, J. E. (2014). The oil curse, institutional quality, and growth in MENA countries: Evidence from time-varying cointegration. Energy Economics, 46, 1–9.

Arai, Y., & Kurozumi, E. (2007). Testing for the null hypothesis of cointegration with a structural break. Econometric Reviews, 26(6), 705–739.

Atkinson, G., & Hamilton, K. (2003). Savings, growth and the resource curse hypothesis. World Development, 31, 1797–1807.

Auty, R. (2001). Resource abundance and economic development. World institute for development economic research of the United Nations University UNU / WIDER. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bhattacharyya, S., & Hodler, R. (2010). Natural resources, democracy and corruption. European Economic Review, 54(4), 608–621.

Boyce, J. R., & Emery, J. C. H. (2011). Is a negative correlation between resource abundance and growth sufficient evidence that there is a “resource curse”? Resources Policy, 36, 1–13.

Bulte, E. H., Damania, R., & Deacon, R. T. (2005). Resource intensity, institutions, and development. World Development, 33, 1029–1044.

Cavalcanti, T. V.d. V., Mohaddes, K., & Raissi, M. (2011). Growth, development and natural resources: New evidence using a heterogeneous panel analysis. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 51, 305–318.

Cockx, L., & Francken, N. (2016). Natural resources: A curse on education spending? Energy Policy, 92, 394–408.

Colletaz, G., & Hurlin, C. (2006). Threshold effect in the public capital productivity: An international panel smooth transition approach. University of Orleans working paper. Growth, investment and real rates. Carneige-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 39, 95–140.

Collier, P., & Hoeffler, A. (2004). Greed and grievance in civil war. Oxford Economic Papers, 56, 563–595.

Corden, W. M., & Neary, J. P. (1982). Booming sector and de-industrialization in a small open economy. The Economic Journal, 92, 825–848.

Costantini, V., & Monni, S. (2008). Environment, human development, and economic development. Ecological Economics, 64, 867–880.

Dülger, F., Lopcu, K., Burgaç, A., & Ballı, E. (2013). Is Russia suffering from Dutch disease? Cointegration with structural break. Resources Policy, 38, 605–612.

González, A., Teräsvirta, T., vanDijk, D., 2005. Panel smooth transition regression models. SEE/EFI Working Paper Series in Economics and Finance, No. 604.

Granger, C., & Teräsvirta, T. (1993). Modelling non-linear economic relationships. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gregory, A. W., & Hansen, B. E. (1996a). Residual-based tests for cointegration in models with regime shifts. Journal of Econometrics, 70(1), 99–126.

Gregory, A. W., & Hansen, B. E. (1996b). Tests for the cointegration in models with regime and trend shifts. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 58(3), 555–560.

Gylfason, T. (2001). Natural resources, education, and development. European Economic Review, 45, 847–859.

Hansen, B. (1996). Inference when a nuisance parameter is not identified under the null hypothesis. Journal of Econometrics, 64, 413–430.

Hodler, R. (2006). The curse of natural resources in fractionalized countries. European Economic Review, 50, 1367–1386.

Ibarra, R., Trupkin, D., 2011. The relationship between inflation and growth: A panel smooth transition regression approach. Research network and research centers program of Banco central del Uruguay (working paper).

Im, K. S., Pesaran, M. H., & Shin, Y. (2003). Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics, 115, 53–74.

Jansen, E., & Teräsvirta, T. (1996). Testing parameter constancy and super exogeneity in econometric equations. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 58, 735–763.

Kaufman, D., Kraay, A., Mastruzzi, M., 2008. Governance matters VII: Aggregate and individual governance indicators1996–2007. World Bank policy research working paper no. 4654.

Kolstad, I., & Wiig, A. (2009). It's the rents, stupid! The political economy of the resource curse. Energy Policy, 37, 5317–5325.

Komarulzaman, A., Alisjahbema, A., 2006. Testing the natural resource curse hypothesis in Indonesia: Evidence at the regional level. Working paper in economics and development studies no. 200602, Department of Economics, Padjadjaran University.

Leite, C.,Weidman, J., 1999. Does mother nature corrupt? IMF working paper 99/85.

Luukkonen, R., Saikkonen, P., & Teräsvirta, T. (1988). Testing linearity against smooth transition autoregressive models. Biometrika, 75, 491–499.

Mehlum, H., Moene, K., & Torvik, R. (2002). Institutions and the resource curse. Department of Economics Memorandum, 29. Norway: University of Oslo.

Mo, P. H. (2000). Income inequality and economic growth. Kyklos, 53, 293–316.

Mo, P. H. (2001). Corruption and economic growth. Journal of Comparative Economics, 29, 66–79.

Neary, J. P., & van Wijnbergen, S. J. G. (1986). Natural resources and the macroeconomy. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Neumayer, E. (2004). Does the “resource curse” hold for growth ingenuine income as well? World Development, 32(10), 1627–1640.

Papyrakis, R., & Gerlagh, R. (2004). The resource curse hypothesis and its transmission channels. Journal of Comparative Economics, 32, 181–193.

Papyrakis, E., & Gerlagh, R. (2007). Resource abundance and economic growth in the United States. European Economic Review, 51, 1011–1039.

Paul C (2003) Natural resources, development and conflict: channels of causation and policy interventions. World Bank.

Ross, M. L. (2003). Oil, drugs and diamonds: The varying roles of natural resources in civil war. In K. Ballentine & J. Sherman (Eds.), The political economy of armed conflict (pp. 47–72). Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Sachs, J. D., & Warner, A. M. (1995). Natural resource abundance and economic growth. In NBER working paper, 5398. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Sachs, J., Warner, A., 1997. Natural resource abundance and economic growth. NBER working paper no.5398.

Sachs, J. D., & Warner, A. M. (1999). The big push, natural resource booms and growth. Journal of Development Economics, 59, 43–76.

Sala-i-Martin, X., & Subramanian, A. (2003). Addressing a natural resource curse: An illustration from Nigeria. Journal of African Economies, 22, 570–615.

Sarmidi, T., Law, S. H., & Jafari, Y. (2014). Resource curse: New evidence on the role of institutions. International Economic Journal, 28, 191–206.

Shuai, S., & Zhogying, Q. (2009). Energy exploitation and economic growth in Western China: An empirical analysis based on the resource curse hypothesis. Frontiers of Economics in China, 4, 125–152.

Smith, B. (2015). The resource curse exorcised: Evidence from a panel of countries. Journal of Development Economics, 116, 57–73.

Teräsvirta, T. (1994). Specification estimation and evaluation of smooth transition autoregressive models. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 89, 208–218.

Tiba, S. (2019a). Revisiting and revising the energy-growth nexus: A non-linear modeling analysis. Energy, 178, 667–675.

Tiba, S. (2019b). Exploring the nexus between oil availability and economic growth: Insights from non-linear model. Environmental Modeling & Assessment, 24(6), 691–702.

Tiba, S. (2019c). Modeling the nexus between resources abundance and economic growth: An overview from the PSTR model. Resources Policy, 64, 101503.

Tiba, S. (2019d). A non-linear assessment of the urbanization and climate change nexus: The African context. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 26(3), 32311–32321.

Tiba, S., & Frikha, M. (2018a). Income, trade openness and energy interactions: Evidence from simultaneous equation modeling. Energy, 147, 799–811.

Tiba, S., & Frikha, M. (2018b). Africa is Africa is rich, Africans are poor! A blessing or curse: An application of Cointegration techniques. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 11(1), 114–139.

Tiba, S., & Frikha, M. (2019a). Sustainability challenge in the agenda of African countries: Evidence from simultaneous equations models. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 11(3), 1270–1294.

Tiba, S., & Frikha, M. (2019b). The controversy of the resource curse and the environment in the SDGs background: The African context. Resources Policy, 62, 437–452.

Tiba, S., & Frikha, M. (2019c). ECK and macroeconomics aspects of well-being: A critical vision for a sustainable future. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 11(3), 1171–1197.

Tiba, S., Omri, A., & Frikha, M. (2015). The four-way linkages between renewable energy, environmental quality, trade and economic growth: A comparative analysis between high and middle-income countries. Energy Systems, 7, 103–144.

Torvik, R. (2002). Natural resources, rent seeking, and welfare. J Journal of Development Economics, 67, 455–470.

Ucar, N., & Omay, T. (2009). Testing for unit root in nonlinear heterogeneous panels. Economics Letters, 104, 5–8.

UNDP. (2009). Human development report 2009—Overcoming barriers: Human mobility and development. New York: United Nations Development Programme.

World Development Indicator Database (CD ROM-2019).

Xu, X., Xu, X., Chen, Q., & Che, Y. (2016). The research on generalized regional “resourcecurse” in China's new normal stage. Resources Policy, 49, 12–19.

Zuo, N., Schieffer, J., 2014. Are Resources a Curse? An investigation of Chinese provinces. Paper presented at the Southern Agricultural Economics Association (SAEA) Annual Meeting Dallas, Texas.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Highlights

• We attempt to answer the question of which scenario is bad: The “resources curse” or the “resources dependence.”

• We use the PSTR model for 33 countries for the period 1990–2016.

• We pointed out that the oil curse thesis is verified.

• The impact of oil abundance on income factor is more explicit in the oil-abundant economies than in the oil-dependent ones.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tiba, S. The Oil Abundance and Oil Dependence Scenarios: the Bad and the Ugly?. Environ Model Assess 26, 283–294 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10666-020-09737-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10666-020-09737-3