Abstract

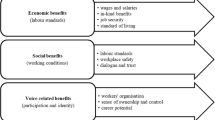

Certification programs seek to promote decent work in global agriculture, yet little is known about their gender standards and implications for female workers, who are often the most disadvantaged. This study outlines the gender standard domains of major agricultural certifications, showing how some programs (Fair Trade USA, Rainforest) prioritize addressing gender equality in employment and others (Fairtrade International, UTZ) incorporate wider gender rights. To illuminate the implications of gender standards in practice, I analyze Fairtrade certification and worker experience on certified flower plantations in Ecuador, drawing on a qualitative and quantitative field research study. (1) I show how Fairtrade seeks to bolster the wellbeing of female workers, addressing their workplace needs via equal employment, treatment, and remuneration standards and their reproductive needs via maternity leave and childcare services. My research demonstrates that for female workers, addressing family responsibilities is critical, since they shape women’s ability to take paid jobs, their employment needs, and their overall wellbeing. (2) I show how Fairtrade seeks to bolster the rights of women workers through individual and collective capacity building standards. My findings reveal how promoting women’s individual empowerment serves as a precondition for collective empowerment, and how targeting traditional labor rights is insufficient for empowering female workers, since their strategic choices are curtailed largely outside the workplace. While Fairtrade certification bolsters the wellbeing and rights of female workers in and beyond the workplace, much still needs to be done before women can claim their rights as workers and citizens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Author’s analysis of 441 Fairtrade News Stories from October 31, 2008 to October 31, 2019.

Fairtrade International commissioned many of the above studies and none provide a systematic analysis of certified flower plantations in Ecuador.

Due to time constraints, all research activities could not be completed on all farms.

Low-level area supervisors are included in the sample; one respondent was excluded because he was promoted to mid-level supervisor.

According to flower industry officials.

The Latin American Fairtrade Producer Network reports similar labor force numbers for Ecuador’s flower plantations but suggests that 56% are women (CLAC 2018).

Samples are merged to facilitate analysis since labor forces do not vary greatly by plantation.

In Ecuador household assets (except those inherited or brought to the partnership) are owned jointly by legally married or registered consensual union partners (Deere et al. 2014).

Primary school is free in Ecuador, but parents must pay for supplies, fees, and transportation, fueling educational disparities (Masala and Monni 2020).

Although the Ecuadorian government in 2008 instituted policies framed as having “a woman's face”—including recognizing women’s role in ensuring family welfare and identifying care work as part of the “good living” enshrined in the constitution—these policies have done little to address women’s conflicting responsibilities for income earning and caregiving (Lind 2012a).

Female workers’ longer tenure may also reflect restricted alternative job opportunities.

A few women discuss their prior domestic abuse; none discuss ongoing violence.

Company documents confirm that the four plantations have annual sexual harassment training, harassment grievance filings, and disciplinary actions, including firing and demoting supervisors and reassigning workers and supervisors.

It could be that there is equal treatment, but men and women assess this treatment differently.

Greenhouse entrance signs record fumigation timing, chemicals applied, and when workers can reenter.

All residents of Ecuador’s major flower regions appear to have high chemical exposure, whether they work in flowers or not (Handal et al. 2016).

One personnel office has a wallchart depicting worker status and assignments. During my research, no employees were identified as pregnant, three as on maternity leave, and three as nursing.

Martínez Valle (2017) argues that most flower plantations abide by Ecuadorian wage laws.

Company records list further health, safety, and environmental trainings.

One illiterate focus group participant asked that the response chart be read aloud to ensure that her opinion had been correctly recorded.

My research documents female advancement: a secretary promoted to Quality Control Manager, an assistant accountant promoted to Certification Officer, and another Certification Officer elected to provincial office.

Women in my survey report having less money available for personal use then men. When asked to identify their purchases, 79% of women identified items for family members, not themselves.

Confirming findings by Grosse (2016).

Henderson (2018) argues that in Ecuadorian floral regions most people identify as “peasants” rather than “workers,” even though they live largely off wages.

Ecuador’s major rural union admits to historically prioritizing men’s concerns (FENACLE 2011).

Although I find no statistically significant relationship between Premium Committee experience and gender, women in my study are less likely to have been members than men, and less likely to have served on the Premium than the Workers’ Committee.

Premium Committee records list women and men equally as project beneficiaries.

This meeting, which I attended, was not a General Assembly where projects are selected. The laundry idea was introduced to gauge interest prior to project proposal development.

Abbreviations

- ILO:

-

International Labour Organization

- NGO:

-

Non-governmental organization

- SDG:

-

Sustainable Development Goal

- UN:

-

United Nations

References

Anner, M. 2012. Corporate social responsibility and freedom of association rights. Politics & Society 40: 609–644.

Auld, G., S. Renckens, and B. Cashore. 2015. Transnational private governance between the logics of empowerment and control. Regulation & Governance 92: 108–124.

Bacon, C. 2010. A spot of coffee in crisis: Nicaraguan smallholder cooperatives, fair trade networks, and gendered empowerment. Latin American Perspectives 372: 50–71.

Barrientos, S. 2019. Gender and work in global value chains: Capturing the gains? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Barrientos, S., and S. Smith. 2007. Do workers benefit from ethical trade? Third World Quarterly 28 (4): 713–729.

Barrientos, S., L. Bianchi, and C. Berman. 2019. Gender and governance of global value chains: Promoting rights of women workers. International Labour Review. 158: 729–752.

Bartley, T. 2012. Certification as a mode of social regulation. In Handbook on the politics of regulation, ed. D. Levi-Faur, 441–452. Northhampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Bartley, T. 2018. Rules without rights: Land, labor, and private authority in the global economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Benería, L. 2003. Gender, development, and globalization. New York: Routledge.

Besky, S. 2013. The darjeeling distinction: Labor and justice on fair-trade tea plantations in India. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Blumberg, R., and A. Salazar-Paredes. 2011. Can a focus on survival and health as social/economic rights help some of the world’s most imperiled women in a globalized world? In Making globalization work for women: The Role of social rights and trade union leadership, ed. V. Moghadam, S. Franzway, and M.M. Fonow, 123–156. Albany: SUNY Press.

Calkin, S. 2016. Globalizing ‘girl power’: Corporate social responsibility and transnational business initiatives for gender equality. Globalizations 132: 158–172.

CLAC (Latin American and Caribbean Network of Fair Trade Small Producers and Workers). 2018. Fairtrade flowers from Ecuador. https://clac-comerciojusto.org/en/2018/02/fairtrade-flowers-ecuador/. Accessed January 22, 2020.

Deere, C.D., J. Contreras, and J. Twyman. 2014. Patrimonial violence: A study of women’s property rights in Ecuador. Latin American Perspectives 41 (1): 143–165.

Deere, C.D., and J. Twyman. 2012. Asset ownership and egalitarian decision making in dual-headed households in Ecuador. Review of Radical Political Economics 44: 313–320.

Distelhorst, G., and R. Locke. 2018. Does compliance pay? Social standards and firm-level trade. American Journal of Political Science 62 (3): 695–711.

Elson, D. 1999. Labor markets as gendered institutions: Equality, efficiency and empowerment issues. World Development 27 (3): 611–627.

Expoflores. 2019. Informe anual de exportaciones. Quito: EXPOFLORES.

FAO (United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization). 2010. Agricultural value chain development: Threat or opportunity for women’s employment? Gender and rural employment policy brief #4. Rome: FAO

FAO (United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization). 2011. The state of food and agriculture 2010–11: Women in agriculture—closing the gender gap for development. Rome: FAO.

FAO (United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization). 2017. FAO work to promote decent rural employment. Rome: FAO.

FAS (Foreign Agricultural Service). 2009. Ecuador fresh flower industry situation. Quito: FAS.

FENACLE. 2011. Condiciones de trabajo y derechos laborales en la floricultura Ecuatoriana. Quito: FENACLE.

Fransen, L. 2012. Corporate social responsibility and global labor standards. New York: Routledge.

Friederic, K. 2014. Violence against women and the contradictions of rights-in-practice in rural Ecuador. Latin American Perspectives 41 (1): 19–38.

FTI (Fairtrade International). 2014. Fairtrade standard for hired labour. Bonn: FTI.

FTI (Fairtrade International). 2015. Theory of change. Bonn: FTI.

FTI (Fairtrade International). 2016a. Gender programme. Bonn: FTI.

FTI (Fairtrade International). 2016b. Gender strategy 2016–2020: Transforming equal opportunity, access and benefits for all. Bonn: FTI.

FTI (Fairtrade International). 2018. Annual report 2017–2018. Bonn: FTI.

FTI (Fairtrade International). 2019a. Monitoring the scope and benfits of Fairtrade flowers. Bonn: FTI.

FTI (Fairtrade International). 2019b. Working together to achieve decent wages, gender equity, and health and safety. Fairtrade News. Bonn: FTI.

FTI (Fairtrade International). 2020a. https://www.fairtrade.net/about-fairtrade/fairtrade-system.html. Accessed January 21, 2020.

FTI (Fairtrade International). 2020b. Our vision and mission. https://www.fairtrade.net/about/mission. Accessed January 21, 2020.

Grosse, C. 2016. Fair care? How Ecuadorian women negotiate childcare in fair trade flower production. Women’s Studies International Forum 57: 30–37.

Handal, A., and S. Harlow. 2009. Employment in the Ecuadorian cut-flower industry and the risk of spontaneous abortion. BMC International Health and Human Rights 9 (1): 25.

Handal, A., L. Hund, M. Páez, S. Bear, C. Greenberg, R. Fenske, and D. Barr. 2016. Characterization of pesticide exposure in a sample of pregnant women in Ecuador. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 70 (4): 627–639.

Hausmann, R., L. Tyson, and S. Zahidi. 2012. The global gender gap report 2012. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

Henderson, T. 2018. The class dynamics of food sovereignty in Mexico and Ecuador. Journal of Agrarian Change 18 (1): 3–21.

ILO (International Labour Organization). 2000. Employment and working conditions in the Ecuadorian flower industry. https://www.ilo.org/public/english/dialogue/sector/papers/ecuadflo. Accessed August 23, 2019.

ILO (International Labour Organization). 2001. International labour conference to explore "decent work deficit" https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_007843/lang--en/index.htm. Accessed June 8, 2020.

ILO (International Labour Organization). 2012. A manual for gender audit facilitators—participatory gender audit methodology. Geneva: ILO.

ILO (International Labour Organization). 2020. NATLEX: National legislation on labour and social rights. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/. Accessed April 20, 2020.

ILO (International Labour Organization). nd. Decent work. https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/decent-work/lang--en/index.htm. Accessed June 2, 2020.

ILRF (International Labor Rights Forum). 2010. Fairness in flowers. New York: ILRF.

INEC (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Censos). 2016. Reporte de pobreza por consumo Ecuador 2006–2014. Quito: INEC.

ITC (International Trade Centre). 2015. Floriculture. Geneva: ITC.

ITC (International Trade Centre). 2019. Standards map. https://www.standardsmap.org. Accessed June 12 2020.

Kabeer, N. 1999. Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change 30: 435–464.

Kissi, E., and C. Herzig. 2020. forthcoming. Methodologies and perspectives in research on labour relations in global agricultural production networks: A review. Journal of Development Studies 56: 1615–1637.

Korovkin, T. 2003. Cut-flower exports, female labor, and community participation in highland Ecuador. Latin American perspectives 30 (4): 18–42.

Krumbiegel, K., M. Maertens, and M. Wollni. 2018. The role of fairtrade certification for wages and job satisfaction of plantation workers. World Development 102: 195–212.

Lind, A. 2005. Gendered paradoxes: Women’s movements, state restructuring, and global development in Ecuador. College Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Lind, A. 2012. Contradictions that endure: Family norms, social reproduction, and Rafael Correa’s citizen revolution in Ecuador. Politics & Gender 82: 254–261.

Lind, A. 2012. Revolution with a “woman’s face”? Family norms, constitutional reform, and the politics of redistribution in post-neoliberal Ecuador. Rethinking Marxism 24: 536–555.

Lyon, S. 2008. We want to be equal to them: Fair trade coffee certification and gender equity within organizations. Human Organization 68 (3): 258–268.

Lyon, S., J. Bezaury, and T. Mutersbaugh. 2010. Gender equity in fairtrade–organic coffee producer organizations: Cases from Mesoamerica. Geoforum 41 (1): 93–103.

Makita, R. 2012. Fair trade certification: The case of tea plantation workers in India. Development Policy Review 30 (1): 87–107.

Martínez Valle, L. 2017. Agribusiness, peasant agriculture and labour markets: Ecuador in comparative perspective. Journal of Agrarian Change 17 (4): 680–693.

Masala, R., and S. Monni. 2020. The social inclusion of indigenous peoples in Ecuador before and during the Revolución Ciudadana. Development. 62: 167–177.

Meehan, K., and K. Strauss. 2015. Precarious worlds: Contested geographies of social reproduction. Athens: Athens University of Georgia Press.

Moghadam, V., M. Fonow, and S. Franzway. 2011. Making globalization work for women: The role of social rights and trade union leadership. Albany: SUNY Press.

Moser, C. 1989. Gender planning in the third world: Meeting practical and strategic gender needs. World Development 17 (11): 1799–1825.

Nelson, V., and A. Martin. 2013. Assessing the poverty impact of sustainability standards. London: NRI, University of Greenwich.

Nelson, V., and A. Martin. 2015. Fairtrade International’s multi-dimensional impacts in Africa. In Handbook of research on fair trade, ed. L. Raynolds and E. Bennett, 509–531. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Rai, S., B. Brown, and K. Ruwanpura. 2019. SDG 8: Decent work and economic growth—A gendered analysis. World Development 113: 368–380.

Rao, A., J. Sandler, D. Kelleher, and C. Miller. 2016. Gender at work: Theory and practice for 21st century organizations. New York: Routledge.

Rathgens, J., S. Gröschner, and H.V. Wehrden. 2020. A systematic review of alternative trade arrangements in the global food sector. Journal of Cleaner Production. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123208.

Raynolds, L. 2012. Fair trade: Social regulation in global food markets. Journal of Rural Studies 28 (3): 276–287.

Raynolds, L. 2017. Fairtrade labour certification: The contested incorporation of plantations and workers. Third World Quarterly 38 (7): 1473–1492.

Raynolds, L. 2018. Fairtrade certification, labor standards, and labor rights. Sociology of Development 4: 191–216.

Riisgaard, L. 2009. Global value chains, labor organization and private social standards: Lessons from East African cut flower industries. World Development 372: 326–340.

Said-Allsopp, M., and A. Tallontire. 2014. Enhancing Fairtrade for women workers on plantations: Insights from Kenyan agriculture. Food Chain 4 (1): 66–77.

Said-Allsopp, M., and A. Tallontire. 2015. Pathways to empowerment?: Dynamics of women’s participation in global value chains. Journal of Cleaner Production 107: 114–121.

Siegmann, K., S. Ananthakrishnan, K. Fernando, K. Joseph, R. Kulasabanathan, R. Kurian, and P. Viswanathan. 2018. Towards decent work in the tea value chain? The role of Fairtrade certification in South Asian tea plantations. Paper presented at the Fair Trade International Symposium, Portsmouth, UK

Smith, S. 2010. Fairtrade bananas: A global assessment of impact. Institute of Development Studies.

Smith, S. 2015. Fair trade and women’s empowerment. In Handbook of research on fair trade, ed. L. Raynolds and E. Bennett, 405–421. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Smith, S., F. Busiello, G. Taylor, and E. Jones. 2018. Voluntary sustainability standards and gender equality in global value chains. Geneva: ITC.

Terstappen, V., L. Hanson, and D. McLaughlin. 2013. Gender, health, labor, and inequities: A review of the fair and alternative trade literature. Agriculture and Human Values 30 (1): 21–39.

Ulloa Sosa, J., V. López, P. Sambonino, R. Anker, and M. Anker. 2020. Living wage report rural Ecuador. Global Living Wage Coalition. https://www.globallivingwage.org/about/. Accessed 28 Aug 2020.

UN (United Nations). 2019. Sustainable development goals. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment. Accessed December 10, 2019.

UN Women. 2020. Ecuador. https://lac.unwomen.org/en/donde-estamos/ecuador. Accessed January 27, 2020.

US LEAP (US Labor Education in the Americas Project), & ILRF (International Labor Rights Forum). 2007. A valentine’s day report: Worker justice and basic rights on flower plantations in Colombia and Ecuador. Chicago: US LEAP.

van Rijn, F., R. Fort, R. Ruben, T. Koster, and G. Beekman. 2020. Does certification improve hired labour conditions and wageworker conditions at banana plantations? Agriculture and Human Values 37: 353–370.

World Bank. 2002. Empowerment and poverty reduction: A sourcebook. Washington DC: World Bank.

World Bank. 2020. Gender data portal: Ecuador. https://datatopics.worldbank.org/gender/country/ecuador. Accessed January 27, 2020.

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge the National Science Foundation, SBE- Sociology program (award 0920980) for funding a portion of the research presented here. I thank Erica Schelly, Meghan Mordy, and Nefratiri Weeks for their research assistance. Most of all I am indebted to the Fairtrade certified farm owners, managers, and workers in Ecuador and the NGO representatives who informed this study. No funding was received from Fairtrade International or other certification organizations. The views presented here are those of the author and should not be attributed to these individuals or organizations.

Funding

Funding for a portion of this research was received from the National Science Foundation, SBE- Sociology program (award 0920980). No funding was received from Fairtrade International or other certification organizations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Raynolds, L.T. Gender equity, labor rights, and women’s empowerment: lessons from Fairtrade certification in Ecuador flower plantations. Agric Hum Values 38, 657–675 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-020-10171-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-020-10171-0