Abstract

National goals and performance standards were introduced in Sweden during the 1990s as part of a curriculum reform. The intention was to detect shortcomings among students and provide support to those students who did not reach the passing grade in one (or several) subject/s. Despite this reform, approximately one-fourth of the students do not attain a passing grade in all subjects. This study therefore investigates the support provided to low-achieving students in Swedish compulsory school. A questionnaire focusing on support in science studies was distributed to students in grade 9 (N = 1731), and data was analyzed with confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling. Findings show that low-achieving students perceive that they primarily receive “simplifying support,” which involves the lowering of expectations and limiting of students’ opportunities to learn. “Scaffolding support,” which involves changes to practices and holding the same standards for all students, seems to be mainly provided to boys, regardless of achievement level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

National goals and performance standards, including a lowest acceptable level of performance in each subject, were introduced in Sweden during the 1990s as part of a major curriculum reform. The intention of this reform was to present clear standards, which could be used to detect shortcomings among students and provide support to those students who did not reach the passing grade in one (or several) subject/s (Hyltegren 2014). Ideally, all students should therefore be able to reach a minimum level of performance in each subject before leaving compulsory school. Official statistics suggest that these optimistic intentions have not been fully realized and in 2018 approximately one fourth of the students in Sweden did not attain a passing grade in all subjects.Footnote 1

There are, of course, several potential explanations for this situation, some of which could be that: (a) there are difficulties in identifying the students in need of support; (b) students in need of support are identified, but still do not receive any support, for instance because the teacher has no available strategies for providing support or because it is too expensive; (c) students receive support, but the support is not adequate or effective enough; and/or (d) students receive support, but they do not want it, for instance because they find it stigmatizing, or are not motivated to use it, because they do not think it will make any difference. As is apparent from the list of potential explanations above, the question about support is an intricate one, and the ambition of this study is not to address all of this complexity. Instead, the aim is to contribute to the understanding of this intriguing topic, by investigating the support provided to low-achieving students, from the students’ perspective.

Background

Grading in Sweden

In Sweden, students are currently graded from year 6 (12–13 years old) and onwards. Grading is standards referenced (Sadler 2005) and there are so called “knowledge requirements” that specify performance standards for year 3, 6, and 9. The grading scale is from A to F, where A is the highest grade, E is the passing grade, and F means that the student has failed to meet the minimum requirements. In the 9th and final year of compulsory school, students are graded in 17 subjects. For selection purposes, the grades are converted into numbers so that an equivalent to the grade point average (GPA) can be calculated.

Supplemental support or special education support

Swedish compulsory schooling consists of “preschool year,” lower primary (years 1–3), upper primary (years 4–6), and lower secondary (years 7–9). Upper secondary education (years 10–12) is voluntary. Along with municipal or public schools, there are a number of independent schools with public funding, sometimes called “charter schools,” which are tuition free.Footnote 2

Regardless of ownership, Swedish schools are governed by the Swedish Education Act (2010:800), which contains basic principles and provisions for all parts of the school system, such as all students at risk of not attaining a passing grade in at least one subject are entitled to additional support. The magnitude of this support can differ, depending on whether it is provided to low-achieving students or students with special education needs. The latter group, for example including students with ADHD/ADD or dyslexia, are typically provided more extensive support, such as being taught individually or having access to specialized software. Due to the extent of this support, a formal decision must be made by the principal for the support to be implemented and it must be documented in an “action programme” (Swedish National Agency for Education [SNAE] 2015). However, since students with special education needs only comprises approximately 5% of the student population in Sweden (SNAE 2019), in this study, the focus is on low-achieving students (i.e., students not attaining passing grades in all school subjects). These students are provided with so called “supplemental support,” which is typically less extensive as compared with special education support and is most often an integrated part of ordinary instruction (SNAE 2014). No formal decisions are needed in order to implement supplemental support, which means that less is known about this kind of support, as compared with special education support, since it is not always recorded.

The provision of support

There are a number of studies on the support provided to students with special education needs in Swedish schools. For example, the Swedish National Agency for Education (SNAE 2016) has published a report from a survey, investigating how schools work with the availability for students with disabilities. The survey was based on answers from heads of schools (i.e., municipalities for public schools and chairpersons/directors for independent schools), principals, and special education teachers (n = 347, 782, and 414 respectively). The conclusion from this survey is that, although the design of learning environments should ideally be adjusted to the diversity of students’ learning needs, in order to support participation for all students, in Sweden, “too many principals and schools do not provide sufficient conditions for the learning environment to be pedagogically, socially, and physically accessible for students with disabilities” (p. 7, our translation). These findings are in line with earlier surveys, showing, for instance, that approximately 20% of students identified as being in need of support never receive any (SNAE 2003).

The Swedish National Agency for Education also publish statistics on special education support in Sweden on a yearly basis, showing, for instance, that special education support is more prevalent among boys, as compared with girls (SNAE 2019). On the one hand, this could seem reasonable, as girls generally outperform boys in school, but there are also indications suggesting that quiet and shy students, who do not attract any attention, may not receive the support that they need (Andreasson et al. 2005).

The findings above are supported by a recent survey, where Yngve et al. (2019) investigated the perceived need of support by students in upper secondary school, from a student perspective. Findings show that about half of the students (n = 484) had not received any support in the majority of school activities, despite an experienced need for support. The perceived need for support also varied among the students, depending on, for instance, gender, where female gender was associated with an increased likelihood of a perceived need for support.

Adequate and effective support

Students not receiving the support that they need is one problem, another is that, even when provided, the support may not be adequate or effective enough. This raises the question about what adequate and effective support might be.

In relation to adequacy, there are two different views on what is considered adequate support. One is based on the idea that the support should be tailored to the individual student’s specific needs, while the other assumes that the learning activities and the learning environment should be adjusted, in order to include the diversity among students. These two views are reflected in the findings reported by Authors (2018), who performed an interview study with teachers, principals, and special education teachers (N = 54) about supplemental support. Findings suggest that the support provided to low-achieving students could be characterized as either “Supportive and relational,” “Simplifying,” or “General and practical.”

The supportive and relational approach correlates to what Harrison et al. (2013) would call “accommodations,” which are:

/…/ changes to practices in schools that hold a student to the same standard as students without disabilities (i.e., grade-level academic content standard) but provide a differential boost (i.e., more benefit to those with a disability than those without) to mediate the impact of the disability on access to the general education curriculum (p. 556).

This approach also has a close relationship to the concept of “scaffolding,” which means that it is provided when students need it, but then progressively removed (Van de Pol et al. 2010). Examples of such supportive and relational support provided by the respondents in the study by Authors (2018) include communicating expectations, helping students to structure their work, giving feedback, and building relationships. With the exception of building relationships, this support is thus characterized by being subject-specific and integrated in the ongoing classroom work, where low-achieving students are provided with support, so that they may engage with the same tasks as the other students.

A simplifying approach, on the other hand, correlates to what Harrison et al. (2013) would categorize as “modifications,” which are “changes to practices in schools that alter, lower, or reduce expectations to compensate for a disability” (p. 556). What the teachers do is therefore to reduce the complexity and difficulty of teaching materials and tasks, so that the low-achieving students may focus on less demanding task, such memorizing facts or basic skills training. According to previous research (Andreasson 2007; Isaksson 2009; SNAE 2003), basic skills training seems to be one of the most common support actions in Swedish schools, frequently associated with changes of the textbook used.

Finally, the general and practical approach to support was primarily universal and applicable across different subjects. Examples of such support were using the whiteboard in a structured manner, or regularly reminding students about what they are expected to do.

As argued by Jönsson (2018), the different approaches to support offer different opportunities for student learning and motivation. For example, when restricting the educational content and depth, as in the simplifying approach, this clearly limits students’ opportunities to learn. However, there may also be other, less obvious, drawbacks, such as the simplifying approach not necessarily supporting student academic self-efficacy (i.e., the belief about the personal capabilities to perform an academic task and reach the established goals; see, e.g., Schunk et al. 2013), since the students do not succeed on “real assignments,” only on restricted ones. This differs from accommodations, where more support is provided to low-achieving students, so that they may work with the same tasks as the other students. Accommodations may therefore also avoid the potentially stigmatizing effect of doing other assignments (Ingestad 2006), which is an inescapable part of simplifying approaches. Regarding the general and practical approach to support, some of these adjustments may qualify as accommodations, but since they are not related to the subject/content of teaching, any influence on student performance is likely to be indirect, for instance by reducing off-task or disruptive behavior. Furthermore, these adjustments are typically tailored to the individual student’s specific needs and do not involve an adjustment of the learning environment.

The effectiveness of support is another line of research. For example, Harrison et al. (2013) performed a systematic review on adjustments for students with “behavioral challenges,” but found very little evidence supporting the effectiveness of commonly recommended adjustments (e.g., shortened task length or adaptive furniture), noting that the lack of research in this area is surprising in the “era of evidence-based interventions.” In a Swedish context, Giota and Lundborg (2007) used statistical data from approximately 17,000 students in a large longitudinal study, and present findings indicating a negative correlation between students’ final grades and the provision of support. Of course, this negative relationship is not likely to have been caused by the special education support. Rather, results from cognitive tests suggest that the preconditions for attaining the requirements for passing grades tend not to be optimal for these students. The findings do suggest, however, that the support provided has not been able to adequately compensate for the shortcomings experienced by students in need of support.

The Swedish Schools Inspectorate (2016) has performed an inspection focusing on supplemental support, emphasizing that low-achieving students not only need to be identified as individuals in need of support, but that their specific needs have to be identified as well. Unless the specific needs are known, matching students’ difficulties with adequate support becomes problematic. This was seen in the majority of schools covered by the inspection, where a number of students were provided with similar support, irrespective of their individual needs. This points to another difficulty with the view that the support should be tailored to the individual student’s specific needs, rather than adjusting the learning environment as a whole, since it requires schools to identify students’ specific needs, as well as to provide them with adequate support.

Adding to the complexity of this question, research also suggests that different kinds of difficulties may be identified differently (Isaksson et al. 2007). For example, while learning difficulties are often identified through the use of tests (e.g., national tests and screening tests), behavioral problems tend to be identified by teachers as part of ordinary teaching, possibly because standardized instruments are not available. This means that students with learning difficulties can be identified and assessed with greater precision, whereas the identification of behavioral/motivational problems depends on more intuitive “measures.” This difference may contribute to the fact that support is often provided quite early during compulsory school for students with learning difficulties, usually in year 3 or 4 (Giota and Lundborg 2007), while other kinds of support, such as “self-contained classrooms” with smaller groups of students, become increasingly common in later years (SNAE 2019). As shown by official statistics, the proportion of students with “action programmes” increases from grade 1 to grade 5, after which it decreases, and then increases again so that the highest proportion of students with “action programmes” can be found in the last year of compulsory school. All kinds of support are more common among boys (SNAE 2019).

Student motivation

In Jönsson (2018), the categories of support were discussed in relation to academic self-efficacy and “self-determination theory” (SDT). SDT focuses on how the social-contextual conditions affect student motivation (Ryan and Deci 2000), which in turn influences how the students accept and use the support provided.

According to SDT, student motivation will increase if certain needs (i.e., autonomy, competence, and relatedness) are supported by the learning environment. For example, if students feel competent when performing a task, the likelihood of engaging with similar assignments increases, whereas feeling incompetent (for instance due to the task being too difficult) may reduce students’ motivation to engage with forthcoming assignments. The situation is comparable for students’ academic self-efficacy, since self-efficacy influences how students engage with their assignments based on their perceived capabilities to perform the task (see, e.g., Keller Carman 2015). For example, if low-achieving students anticipate that they are unable to succeed, they may find ways to avoid the task, rather than investing the effort needed to learn and improve. In addition, as suggested by SDT, student motivation will not necessarily be enhanced only by feeling competent, if there is no sense of autonomy as well. This means, for instance, that students have to attribute their success to their own efforts and/or their own choices (Ryan and Deci 2000).

Relatedness is another factor that, according to SDT, is thought to influence students’ motivation. Feelings of relatedness may come from peer collaboration and/or a positive relationship with the teacher. It has been suggested that low-achieving students may experience a greater need for such relationships (Hornstra et al. 2015) and there are studies demonstrating a positive association between student–teacher relationships and academic achievement (Sointu et al. 2017).

If viewing the “Supportive and relational” approach from an SDT perspective, there is considerable agreement. The scaffolding provided by the teacher supports students’ perceptions of autonomy and competence, and the approach also includes a relational dimension. As stated by some of the teachers in the study by Jönsson (2018), building relationships is a core strategy when working with low-achieving students. Although providing an easier version of the assignment may be seen as a way to support student competency, just as allowing students to select an appropriate task might be perceived as a way to support student autonomy, the simplifying approach may for several reasons not be successful in increasing students’ intrinsic motivation. First, as mentioned above, low-achieving students are likely to anticipate low performance, making these students avoid tasks they feel unable to succeed on, instead choosing less demanding assignments (Keller Carman 2015). Allowing students to select what they perceive as an appropriate task may therefore not be seen as an authentic choice by the students, if they do not think that they can succeed on more complex assignments. Furthermore, success on a simplified task may not count as “real success,” which means that their self-efficacy, nor their intrinsic motivation, is likely to increase.

Aim and research questions

This article started with the observation that not all students receive passing grades in Swedish compulsory school, despite the intentions of the curricular reform and the Swedish Educational Act. Previous research points to several potential explanations for this observation. First, there are a number of students who do not receive any support, even if they are entitled to support. There may also be a tendency towards primarily providing support to boys with behavioral problems, at least when the students grow older, while quiet girls do not receive the support that they perceive that they need. Second, even if provided with support, it may not be adequate or effective. In particular, there is a difference between support that involves an adjustment of the learning environment, and support that is tailored to the individual student, which requires not only that the student’s needs are identified with some precision, but also that appropriate (individual) support is coupled to these specific needs. In relation to the latter, support that lower, or reduce, expectations is especially problematic, since it not only limits students’ opportunities to learn, but may also affect students’ motivation. From an SDT perspective, it is assumed that support provided to low-achieving students need to balance the three dimensions of SDT (i.e., autonomy, competence, and relatedness) in order positively affect students’ motivation. It has also been suggested that low-achieving students have a greater need for relatedness, as compared with high-achieving students.

Currently, however, it is not known to what extent that the support provided to low-achieving students is adequate, neither in terms of being “supportive and relational” or “simplifying,” nor whether it balances the three dimensions of SDT. The current study therefore aims to further the understanding of the adequacy of supplemental support to low-achieving students, by investigating students’ perceptions of support in Swedish compulsory school. The specific research questions are:

-

(a)

What kind of support do students perceive that they receive?

-

(b)

Do students who differ with regard to gender, achievement level, and educational background, experience different kinds of support?

Method

Participants

The subjects were 1731 ninth grade students born in 2003, who left compulsory school in 2018 (age 15–16). This is a sample from the whole population (N = 5203) of ninth graders in a large city in Sweden, which means that the response rate was approximately 33%. Full information is available for subject grades, national test results, gender, family educational background, and questionnaire data. In total, students from 79 different schools are included in the analyses. The questionnaire was distributed by Statistics Sweden to the students’ home addresses with instructions on how to respond. The students could respond either on paper or by logging in to a webpage. Full information was given to the participants on ethical issues and that participating was voluntary. The questionnaire and register data were compiled by Statistics Sweden.

Measures and variables

Low- and high-achieving students (based on GPA)

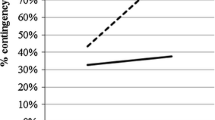

In 9th grade (15–16 years old), teachers grade their students in 17 subjects (Swedish, English, Mathematics, Foreign Language, History, Social Sciences, Geography, Religion, Music, Drawing, Athletics, Biology, Physics, Chemistry, Home Economics, and Natural Sciences) on a scale with six steps, from fail (F) and pass (E) to pass with special distinction (A). Since the grades are used for selection purpose, they are converted into numbers from 0 (F) to 20 (A). Teachers’ grading therefore results in a sum with values ranging from 0 to 320 (i.e., the GPA equivalent). This GPA equivalent is on a continuous and equidistant scale. GPA data from 9th grade was used to create a measure of low and high achievement. The cutoff between low-and high achievers was set to 199 points on the GPA measure in order to include students below and just above the requirement of 12 passing grades for entering upper secondary education. Students with 0–199 points on the GPA9 scale were placed in the category of low achievers and students with 200–320 points are placed in the category of high achievers (see Fig. 1). The dummy variable “low” was coded: 0 = 200–320 points, and 1 = 0–199 points. Among the students, 16.4% (N = 284) were coded as 1 (low achievers) and 83.3% (N = 1442) were coded as 0 (high achievers).

Gender and family educational background

Gender is a dummy variable where boys were coded 0 and girls 1. Among the students, 42.6% were boys (N = 737) and 57.4% were girls (N = 994). Family educational background is a continuous variable with five categories, where 1 = compulsory school or less (6.4%; N = 111); 2 = vocational upper secondary education for 2 or 3 years (6.4%; N = 111); 3 = vocational or theoretical upper secondary education for 3 or 4 years (18.5%; N = 321); 4 = university studies for 2 or 3 years (25.2%; N = 436); 5 = 4 years of university studies or more (33.1%; N = 573). The family educational background variable is abbreviated “FamEd.”

Questionnaire data

The questionnaire data was collected during the spring of 2018, when the students were in 9th grade. The items in the questionnaire (N = 20) were taken from established instruments: “Commitment to school” (Thornberry et al. 1991), screening instrument for Learning Disabilities (Glenn et al. 1997), and “Teacher as social context questionnaire (TASC)” (Wellborn et al. 1988). The items in these scales were translated and modified in order to fit the Swedish school context, the target group of the questionnaire, and the purpose of the study. The items are presented in Table 1. The five scales in the questionnaire are called: Attitudes to School (AttSc), Learning Difficulties (LDiff), Scaffolding Support (ScSup), Simplifying Support (SiSup), and Relational Support (ReSup). The two constructs ScSup and ReSup both relate to the category “Supportive and relational” support in Jönsson (2018), but relational support has been assigned to a separate scale. This is an adaptation to research in SDT, where the relational dimension has been shown to function somewhat differently, as compared with autonomy and competence (see section on self-determination theory above). The scale SiSup, on the other hand, has a direct correspondence to the simplifying approach in Jönsson (2018).

The items have five response categories. Examples of items are as follows: Attitude to School (AttSc) was measured by items such as “I like school” and “I do well in school.” Learning Difficulties (LDiff) was measured by items such as “I read slowly” and I find it difficult to understand problem solving in mathematics.” Scaffolding Support (ScSup) was measured by items such as “Teacher divides the assignments into smaller parts” and “Teacher tells you what to do step by step.” Simplifying Support (SiSup) was measured by items such as “The teacher hand out an assessment rubric” and “The teacher let you choose between tasks with different degrees of difficulty.” Relational Support (ReSup) was measured by items such as “My teacher likes me” and “I can trust my teacher in important matters.”

Students’ answers to these five scales are assumed to represent latent constructs, reflecting their attitudes to school and schoolwork, as well as their perceptions of learning difficulties and different types of support provided to them by their teachers, as part of teaching in natural sciences. Natural sciences were chosen since the simplifying approach was more frequently expressed by teachers in natural sciences, as compared with teachers in other subjects, in the study by Jönsson (2018).

Method of analysis

In order to investigate the relations between low-achieving students’ self-reported attitudes to school and schoolwork, learning difficulties, and different types of support, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM) were used. First, five separate measurement models were estimated, where a latent variable was created designed to reflect attitudes towards school and school work (AttSc), learning difficulties (LDiff), scaffolding support (ScSup), simplifying support (SiSup), and relational support (ReSup). The standardized factor loadings for each of the five one-factor models were substantial, ranging from .45 to .93. (F1 = .463–.831; F2 = .617–.885; F3 = .719–.813; F4 = .448–.772; F5 = .772–.930).

Several steps then followed in the modeling process. In the first model (A), the five factors (AttSc, LDiff, ScSup, SiSup, and ReSup) were estimated in a measurement model with covariances between them. In a second model (B), gender and educational background were related to all the five factors (AttSc, LDiff, ScSup, SiSup, and ReSup). In the final step, a baseline model (C) was estimated with the dummy variable for low- and high-achieving students related to the five factors (AttSc, LDiff, ScSup, SiSup, and ReSup). Then, the final model (D) was estimated with the background variables gender and educational background added to the baseline model.

The intra-class correlations (ICC) were analyzed in the Mplus program by conducting full two-level CFA models. The threshold for applying full two-level models is about 10% (Muthén and Satorra 1995). The ICC for the variables were below 10%, except for the indicators reflecting scaffolding support (ScSup). The ICC’s for the items “Teacher explain to you what is required on a task,” “Teacher tell you what can be better,” and “The teacher hands out an assessment rubric” were 11.3, 12.7, and 18.1%, respectively. Since, the aim of the study is not to investigate school level differences, there is no need to conduct and present a full two-level analysis. However, to take possible clustering effects into account, the “Complex” option in the Mplus program was used. This method compensates for disturbance in the χ2 and standard errors due to clustering effects, but it does not affect the estimates (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2019; Muthén and Satorra 1995). In the complex analyses, the standard errors become larger and the t values become smaller due to loss of information caused by the clustering. The extent of the information loss due to clustering effects is a function of the ICC and the cluster size (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2019).

As measures of model fit, the χ2 goodness-of-fit test and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were used. In order for the model to be acceptable, RMSEA should be below .08 and to be good, the RMSEA should be below .05. RMSEA confidence interval of 95% is presented. The RMSEA is strongly recommended as a tool when evaluating model fit, since it takes both the number of observations and free parameters into account (Jöreskog 1993). The CFI goodness-of-fit measure was also used. CFI should be as close to 1.0 as possible, and values below .95 are not acceptable (Bentler 1990). The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), which is a measure of residuals compared separately for within and between levels, was also used and should be below .08. However, while the model fit is of fundamental importance, it should also be stressed that a model should be meaningful and the parameters interpretable.

For the grades, there were some missing information, which was handled using missing data modeling (Muthén et al. 1987), which under relatively mild assumptions produces unbiased estimates. The response rate was low, under 50%. However, the amount of internal missing data was low. Missing information was handled using missing data modeling (Muthén et al. 1987), which is a method that makes the assumption that the data is “missing at random” (MAR), which implies that the procedure yields unbiased estimates, when missing is random given the information in the data. This is less restrictive as compared with the assumption that the data are “missing completely at random.” The fact that there are high interrelations among the observed variables provides good possibilities to satisfy the MAR assumption.

The WLSMV estimator in Mplus has been used throughout the analyses. Mplus version 8.4 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2019) was used for modeling purposes and for testing the models.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The number of individuals, means, and standard deviations for the variables low, gender, family educational background, and questionnaire data are presented in Table 2. The response rate was relatively low (33%) and the frequency is biased upwards (see Fig. 1). Thus, the sample consists of a larger number of high-achieving students, as compared with the population. The descriptive statistics show that there were missing observations for some of the variables, particularly for family educational background (10.3%) and questionnaire data (0.6–3.9%). Analyses were made in order to investigate possible differences of gender and family educational background in relation to the low variable. Independent t tests were conducted in Mplus (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2019). The result showed significant differences for gender in relation to low: t(1731) = −5.32, p = 0.00. For family educational background, (cut point 3 = vocational or theoretical upper secondary education for 3 or 4 years), the result showed significant differences in relation to low: t(1552) = 8.94, p = 0.00. These differences in low- and high-achieving students related to gender and family educational background are expected and in line with research, since girls and students from families with high educational level achieve higher grades.

The measurement models (models A and B)

The first step was to estimate a measurement model (A) with five factors (AttSc, LDiff, ScSup, SiSup, and ReSup) specified by their respective indicators and with covariances between the factors. The standardized factor loadings for this model were substantial, ranging from .55 to .87 and the fit indices were acceptable (χ2(160, 1731) = 1210.67; RMSEA = .062 [C.I. .058–.065]; SRMR = .057; CFI = .94). Model A is presented in Table 3.

In the next step, gender and family educational background were added to the model and related to the five factors (model B). Model fit indices were good (χ2(190, 1731) = 1128.61; RMSEA = .056 [C.I. .053–.060]; SRMR = .059; CFI = .93). The standardized factor loadings and regression coefficients for model B are presented in Table 3. The estimated factor loadings were similar to those of model A. Gender had significant relations to all the factors, positive and strongest for LDiff (.17), but positive for AttSc (.07) as well. Estimates for ScSup (− .14), SiSup (− .08), and ReSup (− .06) were negative, however, which means that girls report have more learning difficulties and have more positive attitudes to school, but that they receive less of the different types of support, as compared with what boys report. The family educational background variable seemed primarily to be of importance for the factors AttSc, LDiff, and ScSup, and accounted for 2.3, 0.8, and 4.4% of the variance in respective factor. The FamEd variable is on a continuous scale, thus the positive estimate for AttSc (.15) shows that students with parents with a higher level of education report more positive attitudes to school, as compared to students with parents with lower levels of educational background. There are negative relations between FamEd and LDiff (− .21) and ScSup (− .09), indicating that students with parents with low educational background report higher levels of learning difficulties, but perceive that they receive less scaffolded support, as compared to students with parents with higher educational background.

In all, the results show that there are differences related to gender and family educational background for attitudes to school, learning difficulties, and the different types of support the students perceive that they receive.

SEM models for low- and high-achieving students

The final steps in the modeling process were to estimate a baseline model, taking into account achievement level, and then include the background variables in the model. The baseline model (C) was estimated with relations between the dummy variable for low-and high-achieving students (low) and the five factors (Table 4). The complex option in Mplus was used and the goodness-of-fit was good (χ2(175, 1550) = 1279.47; RMSEA = .060, C.I. = .057–.064; SRMR = .057; CFI = .94). The result showed a significant factor loading for low-achieving students on AttSc (− .38), which means that low-achieving students have more negative attitudes to school and school work, as compared with high-achieving students. A positive coefficient for LDiff (.34) indicates that low-achieving students report more learning difficulties, as compared with high-achieving students. There were also significant associations between, on the one hand, low-achieving students and, on the other, scaffolding and simplifying support (ScSup and SiSup). The relationship was strongest for simplifying support (.22), which indicates that low-achieving students report that they receive more of simplifying support, as compared with high-achieving students. The association to relational support (ReSup) was non-significant.

Next, a final model (D) was estimated by including the gender and FamEd variables into model D. The goodness-of-fit was good (χ2(205, 1550) = 1079.04; RMSEA = .052, C.I. = .049–.056; SRMR = .060; CFI = .94) (Table 4). Initially, cross product terms were calculated for the background and the dummy variables and included in the model, but no significant interaction effects were found. The factor loadings for AttSc remained substantial for the low variable, which indicates that low-achieving students have less positive attitudes to school (− .37), as compared with high-achieving students, after taking background variables into account. For LDiff, there was still a strong positive coefficient (.31) for low-achieving students, which means that they report more of learning difficulties, as compared with high-achieving students, after controlling for the background variables. The association between low-achieving students and scaffolding support became non-significant when gender and family educational background variables were taken into account. This means that there were significant gender differences (− .13), where boys report that they receive scaffolding support no matter their achievement level, while associations for family educational background were non-significant. The decreased coefficient for low-achieving students on simplifying support (from .22 to .15), together with a significant and negative coefficient for gender (−.07), suggests that both low achievers (girls and boys) and boys, no matter their achievement level, report that they receive simplifying support.

For gender differences, girls report higher levels of learning difficulties (.20), as compared with boys. For all three types of support, girls also report that they receive less of scaffolding, simplifying, and relational support, as compared with boys. Scaffolding support (ScSup) has the strongest coefficient (− .13) among the support variables.

Overall, low-achieving students report less positive attitudes to school, and higher levels of learning difficulties, as compared with high-achieving students. Low-achieving students also report that they receive more of simplifying support (SiSup) and less of scaffolding (ScSup) and relational support (ReSup) from their teachers, as compared with high-achieving students. There were significant effects of gender for the learning difficulties variable and for all three types of support, girls reporting higher levels of learning difficulties, but receiving less support, as compared with the boys. Family educational background had significant and positive associations to attitudes to school and negative estimates in relation to learning difficulties, which means that students with highly educated parents report more positive attitudes to school, and less of learning difficulties, as compared to students with parents with lower levels of education. Family educational background was not significant for any of the different types of support.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to further our understanding of the adequacy of supplemental support to low-achieving students, by investigating students’ perceptions of support in Swedish compulsory school. This was done by distributing a questionnaire to students in grade 9, and analyzing the data with confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling.

While previous research (SNEA 2003; 2016; Yngve et al. 2019) has suggested that a number of students do not receive any support, the findings from this study seems to suggest that low-achieving students do receive support, although they mostly receive simplifying support. This association was significant, even when taking gender and educational background into account. Findings also show, perhaps not surprisingly, but nevertheless interesting, that low-achieving students, to a lesser extent as compared with high-achieving students, think that the teacher likes them and that they should trust the teacher in important matters. These findings indicate, first, that the support provided to low-achieving students mainly involves the lowering of expectations and limiting of students’ opportunities to learn, and, second, that the support lacks a balance in relation to the three dimensions of SDT (Ryan and Deci 2000), both of which may have negative consequences for students’ learning and motivation.

The results also show that when only considering achievement level in the association between low-achieving students and the five factors, there are significant associations between low-achievers and attitudes to school, learning difficulties, scaffolding, and simplifying support. When taking gender and educational background into account, the result is similar concerning attitudes to school and learning difficulties, but becomes non-significant for scaffolding support, somewhat weaker for simplifying support and stronger for relational support. This means that even when taking the background variables into account, there is still associations between low-achieving students and their attitudes to school and schoolwork, and perceived learning difficulties, regardless of gender and educational background. However, the positive associations between low-achieving students and scaffolding support decrease and become non-significant when gender and educational background are taken into account. This means that it is mainly the boys, no matter achievement level, who perceive that they receive scaffolding support. The same pattern can be seen for simplifying support, but not as strong. The association between low-achieving students and relational support becomes somewhat stronger, which means that boys report that they are provided relational support, while girls do not. This is why the association between low-achieving students and relational support becomes significant, when taking gender differences into account. These findings are similar to previous research showing that support is primarily provided to boys, while less attention is given to girls, possibly due to a dominance of behavioral problems during adolescence, where quiet students may become neglected (Andreasson et al. 2005; SNEA 2019; Yngve et al. 2019). Furthermore, that the association between low-achieving students and relational support was zero, when gender differences were not taken into consideration, indicates that the teachers do not use relational support in order to compensate for the potentially greater need for relatedness among low-achieving students (Hornstra et al. 2015).

Another finding is that educational background does not add to the associations between low-achieving students and scaffolding, simplifying, and relational support. This is interesting because students with well-educated parents have more positive attitudes to school and schoolwork, as compared to students with less-educated parents. Besides, students with less-educated parents perceive that they have learning difficulties to a greater extent, as compared to students with well-educated parents. This means that the support provided does not seem to compensate for differences in students’ educational background, despite the fact that students with less-educated parents reported higher levels of learning difficulties.

School differences

In educational settings and data, differences between schools may be considerable in that students in one school have more in common since they share the same teachers and have other school characteristics in common. In the current study, the result showed that attitudes to school and learning difficulties are two factors that have variance only on individual level. The three support variables had variation on the school level, which means that schools differ in relation to the type of support students report that they receive. Students attending schools with a high level of students with well-educated parents report that they receive less of simplifying support. This association is somewhat smaller for scaffolding support and not significant for relational support. In all, students in all kinds of schools report attitudes to school and learning difficulties to a similar degree, while the type of support they perceive they receive differs across schools.

Educational implications

According to the respondents, low-achieving students mainly receive simplifying support. This is problematic for several reasons. First, there are several disadvantages of simplifying support in relation to students’ learning and motivation. Since such support involves the lowering of expectations to compensate for students’ difficulties, it simultaneously limits students’ opportunities to learn. Furthermore, since the success that students experience involves restricted tasks, and students therefore do not succeed on the same tasks as other students, simplifying support may not necessarily increase students’ academic self-efficacy or intrinsic motivation. There are also consequences for teachers. Jönsson (2018) describes how this approach led to teachers having long lists with adjustments for each specific student and teachers providing four different versions of the same task, so that students could choose a task with a level of difficulty corresponding to their particular profile. Although these practices were common at several schools in the sample, some teachers found it very stressful.

Low-achieving students also perceived that they received relational support to a lesser extent, as compared with high-achieving students. This is problematic since it has been suggested that low-achieving students may be in need of more relational support, as compared with other students, and that there is a positive association between student–teacher relationships and academic achievement (Sointu et al. 2017). Furthermore, since most of the support provided for the low-achieving students seems to be individual, rather than adjusting the learning environment, it involves exerting control over the students, for instance, by checking on them at regular intervals or by offering them specific positions in the classroom. This support may therefore counteract the students’ feeling of autonomy. Jönsson (2018) propose that teaching involving control might still be beneficial for students’ motivation, if provided in combination with relationship building. In this particular case, however, relational support does not seem to balance students’ need for autonomy.

There are indications of low-achieving students receiving scaffolding support, but the findings suggest that it is mainly boys who receive such support. Furthermore, the support provided does not seem to compensate for differences in students’ educational background, despite the fact that students with less-educated parents reported higher levels of learning difficulties. Students with well-educated parents also report that they receive less of simplifying support. An obvious educational implication is therefore that the scaffolding support needs to be provided more broadly, so that more students are able to participate in learning activities, and be held to the same standards as students without learning difficulties.

Limitations

The current study is based partly on self-reported data from students, which means that the findings reflect students’ attitudes, as well as their perceptions of own learning difficulties and support provided. These measures may therefore not necessarily agree with the perceptions of teachers, principals, or other school personnel. The observed gender differences may also partly depend on students’ more or less critical assessment of their own needs. However, meta-analyses of gender differences in academic self-efficacy show no gender differences in science, and gender differences in global academic self-efficacy is generally quite small (Huang 2013).

Another limitation is that the questionnaire is based on students’ perceptions in one subject only (i.e., science), which could have affected the results, for instance by increasing the score for simplified support. It is therefore important not to generalize the findings to other subjects. Yet another limitation is that the number of items in the questionnaire is low, which is an adaptation made in order to increase the number of respondents, including low-achieving students. Still, the response rate was low.

Since the current study is based on students’ perceptions, a natural recommendation for future research would be to perform a corresponding survey for teachers. Although the study by Jönsson (2018) investigated teachers’ views on providing support to low-achieving students, this is a small-scale interview study with limited capacity for generalizing the findings. By distributing a questionnaire to a larger sample of teachers, a more nuanced picture of teachers’ perceptions of support could be drawn, especially since the number of items does not have to be limited in the same way as in the current study. In particular, a comparison could be made, not only with students’ answers, but also between teachers teaching different subjects, to explore possible differences in relation in relation to the support provided.

Notes

See, for instance: https://sweden.se/society/education-in-sweden/#

References

Andreasson, I. (2007). Elevplanen som text – om identitet, genus, makt och styrning i skolans elevdokumentation [The individual education plan as text. About identity, gender, power and governing in pupils]. Doctoral dissertation, Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg.

Andreasson, I., Heimersson, M., & Persson, B. (2005). Elever som behöver stöd men får för lite [students in need of support, but who do not recieve enough]. Stockholm: Swedish Agency for School Development.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative indexes in structural models. Psychology Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246.

Giota, J., & Lundborg, O. (2007). Specialpedagogiskt stöd – omfattning, former och konsekvenser [Special-education support – Proportions, types, and consequences], IPD-report 2007:03. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg.

Glenn, J., Paul Eslinger, P., Chinchilli, V., Eitington, N. J., Martel, J., Salisbury, J., Karwacki, M., & Deegan, D. (1997). Validation of a questionnaire to screen university students for learning disabilities. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 2(3), 213–220.

Harrison, J. R., Bunford, N., Evans, S. W., & Owens, J. S. (2013). Educational accommodations for students with behavioral challenges: a systematic review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 83(4), 551–597.

Hornstra, L., Mansfield, C., van der Veen, I., Peetsma, T., & Volman, M. (2015). Motivational teacher strategies: the role of beliefs and contextual factors. Learning Environments Research, 18(3), 363–392.

Huang, C. (2013). Gender differences in academic self-efficacy: a meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28(1), 1–35.

Hyltegren, G. (2014). Vaghet och vanmakt – 20 år med kunskapskrav i den svenska skolan [Vagueness and powerlessness – 20 years of national knowledge requirements in Swedish schools]. In Doctoral dissertation. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg.

Ingestad, G. (2006). Dokumenterat utanförskap. Om skolbarn som inte når målen [Documented exclusion. About students not reaching the goals]. Doctoral dissertation, Lund: Lund University.

Isaksson, J. (2009). Spänningen mellan normalitet och avvikelse. Om skolans insatser för elever i behov av särskilt stöd [The tension between normality and deviance. About school support for students in need of special-education support]. Doctoral dissertation, Umeå: Umeå University.

Isaksson, J., Lindqvist, R., & Bergström, E. (2007). Mellan normalitet och avvikelse – om skolans insatser för barn och ungdomar i behov av särskilt stöd [Between normality and deviance – about school support for children and adolescents in need of special education support]. In R. Lindqvist & L. Sauer (Eds.), Funktionshinder, kultur och samhälle [Disability, Culture, and Society] (pp. 147–169). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Jönsson, A. (2018). Meeting the needs of low-achieving students in Sweden: an interview study. Frontiers in Education: Special Educational Needs, 3(63).

Jöreskog, K. G. (1993). Testing structural equation models. In K. A. Bollen & J. Scott Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 294–316). Newbury Park: Sage.

Keller Carman, L. (2015). Low–achieving students’ perceptions of their in-class support delivered in a general education setting. Doctoral dissertation, The State University of New Jersey, NJ.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2019). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Muthén, B., & Satorra, A. (1995). Technical aspects of Muthén’s LISCOMP approach to estimate latent variable relations with a comprehensive measurement model. Psychometrica, 60(4), 489–503.

Muthén, B., Kaplan, D., & Hollis, M. (1987). On structural equation modeling with data that are not missing completely at random. Psychometrica, 52(3), 431–462.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78.

Sadler, R. D. (2005). Interpretations of criteria-based assessment and grading in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 30(2), 175–194.

Schunk, D. H., Meece, J. R., & Pintrich, P. R. (2013). Motivation in education. Theory, research, and applications (4th ed.). Harlow: Pearson.

Sointu, E. T., Savolainen, H., Lappalainen, K., & Lambert, M. C. (2017). Longitudinal associations of student-teacher relationships and behavioral and emotional strengths on academic achievement. Educational Psychology, 37(4), 457–467.

Swedish National Agency for Education. (2003). Kartläggning av åtgärdsprogram och särskilt stöd i grundskolan [Survey of action programs for special-education support in compulsory school]. Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education.

Swedish National Agency for Education. (2014). Arbete med extra anpassningar, särskilt stöd och åtgärdsprogram [Working with supplemental support, special-education support, and actions programs]. Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education.

Swedish National Agency for Education. (2015). Support activities in school – what do I need to know as a parent? Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education.

Swedish National Agency for Education. (2016). Tillgängliga lärmiljöer? [Accessible learning environments?] Report 440. Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education.

Swedish National Agency for Education. (2019). Särskilt stöd i grundskolan läsåret 2018/19 [Special-education support in compulsory school the academic year 2018/19]. Dnr: 2018:1562. Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education.

Swedish Schools Inspectorate. (2016). Skolans arbete med extra anpassningar – Kvalitetsgranskningsrapport [The school’s work with supplemental support – Quality review report]. Stockholm: Swedish Schools Inspectorate.

Thornberry, T. P., Lizotte, A. J., Krohn, M. D., & Farnworth, M. (1991). Testing interactional theory: an examination of reciprocal causal relationships among family, school, and delinquency. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 82(1), 3–35.

Van de Pol, J., Volman, M., & Beishuizen, J. (2010). Scaffolding in teacher-student interaction: a decade of research. Educational Psychology Review, 22, 271–297.

Wellborn, J., Connell, J., Skinner, E. A., & Pierson, L. H. (1988). Teacher as social context: a measure of teacher provision of involvement, structure and autonomy support. Technical Report 102. Rochester: University of Rochester.

Yngve, M., Lidström, H., Ekbladh, E., & Hemmingsson, H. (2019). Which students need accommodations the most, and to what extent are their needs met by regular upper secondary school? A cross-sectional study among students with special educational needs. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 34(3), 327–341.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Gothenburg. This work was financially supported by the Swedish Research Council (grant number 2013–2270).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Alli Klapp. Department of Education and Special Education, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg;Sweden. E-mail: alli.klapp@ped.gu.se

Current themes of research:

Assessment and grading practices in school. Consequences of grading on students learning and motivation. The importance of cognitive and non-cognitive competencies for success in school.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

1. Klapp, A. (2019). Differences in educational achievement in norm- and criterion-referenced grading system for children and youth placed in out-of-home care in Sweden. Children and Youth Services Review, 99, 408–417.

2. Klapp, A. (2018). Does academic and social self-concept and motivation explain the effect of grading on students´ achievement? European Journal of Psychology of Education, 33(2), 355-376. DOI: 10.1007/s10212-017-0331-3

3. Klapp, A. (2016). The importance of self-regulation and negative emotions for predicting educational outcomes – evidence from 13-year olds in Swedish compulsory and upper secondary school. Learning and Individual Differences, 52, 29-38.

4. Klapp, A. (2015). Does grading affect educational attainment? A longitudinal study. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 22(3), 302-323.

5. Klapp, A., Cliffordson, C., & Gustafsson, J-E. (2014). The effect of being graded on later achievement: evidence from 13-year olds in Swedish compulsory school. Educational Psychology: An International Journal of Experimental Educational Psychology, 36(10), 1771-1789. DOI: 10.1080/01443410.2014.933176.

Anders Jönsson. Department of Educational Sciences Specializing in Primary and Secondary School, and Special Needs Education, University Kristianstad, Kristianstad, Sweden.

Current themes of research:

Teachers’ grading practices. Consequences of grading young students. Formative assessment and self-regulated learning.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

1. Jönsson, A. (2020). Definitions of formative assessment need to make a distinction between a psychometric understanding of assessment and “evaluative Judgment”. Frontiers in Education: Assessment, Testing and Applied Measurement, 5(2). doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00002

2. Jönsson, A. & Balan, A. (2018). Analytic or holistic: a study of agreement between different grading models. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 23(12). Available online: http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=23&n=12

3. Balan, A. & Jönsson, A. (2018). Increased explicitness of assessment criteria: Effects on student motivation and performance. Frontiers in Education: Assessment, Testing and Applied Measurement, 3(81). doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00081

4. Jönsson, A. (2018). Meeting the needs of low-achieving students in Sweden: an interview study. Frontiers in Education: Special Educational Needs, 3 (63). https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2018.00063

5. Panadero, E., Jönsson, A. & Botella, J. (2017). Effects of self-assessment on self-regulated learning and self-efficacy: Four meta-analyses. Educational Research Review, 22, 74-98.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Klapp, A., Jönsson, A. Scaffolding or simplifying: students’ perception of support in Swedish compulsory school. Eur J Psychol Educ 36, 1055–1074 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-020-00513-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-020-00513-1