Abstract

Improving forest product value chains is considered a means to solve forest-related challenges in the Global South. The ‘Participative Innovation Platform’ (PIP) instrument has been developed to design and to continually adapt solutions and strategies for effective cooperation amongst value chain actors. The instrument is rooted in the action-oriented and social learning approach, combined with the concept of innovation systems. This paper presents findings from three PIPs conducted for upgrading non-timber forest product value chains in Ethiopia (bamboo, natural gums) and Sudan (gum Arabic). A comparative analysis of highest ranked contents revealed similarities in the challenges: lack of government support, poor infrastructure, producers’ lack of knowledge and skills, and lack of market information. Priority upgrading measures focused on producers’ knowledge, skills, and capacity to engage in collective action and to lobby interests, and on capital resources to invest in processing technology. It is concluded that although the PIP instrument presents an innovative way to upgrade forest-based value chains, the instrument requires a long-term process with frequently held platform meetings, conducted by neutral institutions with skilled moderators. Crucial in this process is the need to consistently verify and ensure that all actor groups of the chain are represented, and are confident they will derive benefits from the value chain upgrading.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the Tropics, the trend of forest degradation and conversion to other land uses is still unbroken (Hansen et al. 2013; Weisse and Dow Goldman 2017). Over the past 25 years, forest area declined at rates of about five to ten million ha annually (FAO 2015, p. 19), with annual tree cover loss increasing to seventeen million ha (Weisse and Dow Goldman 2018). Various global initiatives—e.g. tropical timber boycotts, certification schemes, biodiversity and climate conventions or REDD+ programs—have not succeeded in halting this development, and there is no change foreseeable (Darr et al. 2014; European Union 2018).

One challenge for maintaining forest systems is their high complexity, composed of the multitude of interactions and dynamics of their elements (e.g. species, soil, water, climate). The sustainable management of such complex production systems requires comprehensive and innovative interventions. As noted by Pretzsch et al. (2014), this complexity is further increased by the highly complex human social system which is interacting with forest ecosystems. The adaptive management approach is identified as a suitable tool for both the sustainable management of forest ecosystems and the enhancement of participation in steering and governance (Williams 2011; Yousefpour et al. 2012). This is reflected in the increasing relevance of local and non-governmental actors in forest management, which join the arena to bring in their various interests, and complement the state forestry administration’s control and decision-making. Here the paradigm shift is obvious, from top-down central control towards multi-stakeholder participation and planning models such as collaborative forest management or co-management arrangements (Katila et al. 2014; Pretzsch 2014; World Bank 2014).

Another challenge is financing sustainable forest management, for endogenous creation of funds; the forest utilization must not only cover the cost of extraction of products, but also the cost for sustainable management. In common pool situations where the products and services of the resource are covering the management and governance efforts, sustainable utilization can be assured by "congruence" between the cost of managing and protecting the natural resource and the benefits obtained from them (Ostrom 1990). In situations where resource utilization does not fully cover these efforts, actors with intrinsic interest (e.g. NGOs) or the society (state) may bear the remaining management and protection cost, otherwise the resource is exposed to degradation and conversion. Apart from funding by public institutions or initiatives, revenues from the sale of forest commodities constitute a key source for funding the cost of sustainably managing and protecting forest resources. After decades of forest exploitation, there are hardly any trickle-down effects from exports and processing industries that have virtually arrived and maintained the timber and non-timber production systems (Belcher et al. 2005; Ticktin and Shackleton 2011; Achard et al. 2014). The challenge is therefore to design innovative and proactive strategies to maintain the existing forests, in order to ensure the sustainable supply of forest products and services, while stabilizing rural areas.

A proactive way to enhance value-addition for forest products is through the innovation of new products, increase in the efficiency of transactions within the value chain, and by ensuring a fairer distribution of the value added amongst the chain actors. Value added is created by processing primary forest products and combining these with other resources along the value chain (Poschen et al. 2014). Very often, the price paid for forest products at the production level rewards the removal cost only. The costs for activities linked to sustainability and the maintenance of forest resources—e.g. planning, enforcement of regulations, infrastructure, fire management and silviculture—are not covered. A fair payment for the forest products, which covers both cost of harvest and cost of sustainable resource management, is key for the sustainable maintenance and conservation of tropical forest resources by local actors.

While multi-stakeholder innovation platforms are frequently employed for upgrading agrarian livestock and cash crop product chains (Nederlof et al. 2011; Sanyang et al. 2016), they are quite new for the forestry sector in most countries. Upgrading of forest-based value chains requires basic transformations: from production at the lowest quality level to diversified qualities as requested by clients; optimization of supplier–buyer coordination; producer empowerment and entrepreneurial competencies. To support these transformations, the Participative Innovation Platforms (PIPs) instrument has been developed, for the design and continuous adaptation of tailor-made solutions and strategies, and for effective cooperation amongst value chain actors. A PIP is an “organized social space involving diverse actors who collaborate to solve common problems by building mutual respect and trust, promoting knowledge contribution and sharing, diagnosing and analyzing their value chain, and agreeing on their course of action” (Pretzsch and Auch forthcoming, p. 24).

The PIP instrument was tested in an R&D project for NTFP value chain upgrading, referred to as CHAnces IN Sustainability—promoting natural resource based product chains in East Africa (CHAINS). This paper summarizes and analyses three PIP processes in the country contexts of Ethiopia and Sudan, discusses the results and findings of its application in the context of NTFP value chain upgrading, and explores future options to improve and subsequently implement PIP processes. For the comparative analysis of the studied processes, similar problems and solutions were grouped and coded.

The PIP Instrument

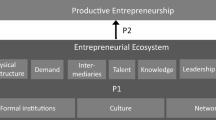

The PIP instrument draws on action-oriented and social learning approaches, combined with the concept of innovation systems. It is based on the assumption that the interaction and synthesis of the two knowledge and expertise spheres—external and scientific versus internal and local—lead to innovation and upgrading (Pretzsch and Auch forthcoming). Typically, researchers or development agents approach the actors of a value chain and suggest conducting a PIP for initiating an upgrading process. Representatives from all relevant actor groups of the value chain come together to conduct a PIP, either as a single event or as an ongoing process with repeated meetings. A PIP follows a sequence of phases, starting with preparation, followed by an initial workshop and subsequent follow-up activities, as displayed in Fig. 1.

A PIP follows a strict participatory approach. While the initiation might be driven by external experts, during the process they pass on the baton to value chain actors, who will negotiate and decide on what action(s) to take, while the initiators withdraw and consult on demand only (Fig. 2). To be effective, PIPs have to be held repeatedly. Innovation is created in an ongoing process of diagnosis, agreement on a course of action, implementation of the action, evaluation, and agreement on the future course of action. A PIP process requires a formalized institutional frame, an organization with the mandate to conduct workshops, and result-oriented moderation.

It is obvious that the composition of the actors of a PIP will determine and shape the outcomes. To handle this sensitive issue, and for sustainable results, the initiators must make sure that a sound stakeholder analysis is conducted and used for the selection of participants and moderators.

Moderators play a crucial role in guiding and facilitating the PIP process towards innovation. Discussions amongst actors on chain upgrading affect potential losers and winners. In such struggles, a moderator must be able to overcome established hierarchies, withstanding against powerful and dominating or impertinent participants, and at the same time, elicit the opinion of powerless, shy and quiet representatives. Best experiences are made with teams of two moderators, both competent, neutral and respected persons, sharing the moderation task and complementing each other in guiding the discussions and negotiations (Klebert et al. 2000; Alemu and Auch 2016).

Application of the PIP Instrument in NTFP Value Chains

Socio-Economic Context of the Studied Value Chains

For the studied products (gum Arabic in Sudan, frankincense and bamboo in Ethiopia), abundant information is available on the physical properties and the ecology of the plants. Less is known about the organization of the product chains and on innovative product development options. Challenges and features observed in the CHAINS project are summarized in this section.

Forest Products are Competing with Substitute Products

NTFPs compete with substitute products that serve the same purpose. Established products have their market niche with relatively fixed shares and prices. For example, the duka, a common bamboo stool in Ethiopia, had in 2014 an average price of 6.95 USD; the most competitive products were a plastic imports which cost 4.63 USD, and the solid wood version costing 12.87 USD (Frysch 2014). Obviously, an increase in price for the bamboo duka would be likely to result in a smaller market share. The actors within the value chain compete together for the total value added, hence a more efficient chain with reduced transaction (and other) costs would release a higher value added for distribution amongst the chain actors.

NTFPs are Commercial Goods

If NTFPs have an export market, actors are attracted to enter into processing and trade to gain foreign exchange, even when this falls below the cost price. However, market liberalization in Sudan has boosted the export of raw gum Arabic, but not stimulated its production, so local processing volume has witnessed a decline (Tarig et al. 2017). This is a negative development for the national economy.

Middlemen are Crucial Actors

Middlemen are the link between producers and processors, and usually coordinate the NTFP value chains. Especially in the seasonally organized gum and resin sector, they aggregate the small quantities of the dispersed production, and finance it in advance, bearing risks and transaction cost. Usually, they establish a two-way business by exchanging food and petty trade-stuff (or credit) against the NTFP as “payment”, using a network of village traders. However, value chains that are coordinated by middlemen are rather short-term profit oriented; they lack an orientation on specific qualities as required from downstream clients. Downstream processors’ and international buyers’ interest in quality and uninterrupted supply starts at central market places where products are graded and aggregated. The sustainability of the production systems is rather beyond their horizons.

NTFP Production (Collection) is a Low-Return Income Alternative Only

The threshold volume to enter most NTFP collection businesses is quite low; as soon as profitability increases, additional producers enter into collection, resulting in overharvest and in a subsequent collapse in prices hence boom-bust cycles, as noted by Sills et al. (2011). Despite increasing demand, the prices paid to the producer or collector remains small, and a large share of the value added is captured by middlemen and processors. Producers are usually weak market partners, being powerless “price takers”.

Value Chain Arrangements Do Not Provide Incentives for Product-Quality to Producers

Typically, traders buy the NTFPs from the producer in bulk, irrespective of the quality; producer receive a price based on product volume. In the case of bamboo for instance, a mix of mature and immature culms, thick and thin, short and long, are bought. Middlemen choose the cheapest way to measure the volume, either by quantity or weight. The non-consideration of quality is a signal that producers (collectors) tend to focus on increasing product volume at the expense of quality. As feedback, processors tend to lower prices in a bid to mitigate possible losses that might arise from the acquisition of low quality lots. The causal loop effect pushes both price and quality downwards. Such market signals discourage producers from re-investing in their production system. This renders NTFP production unattractive; the production systems are rather over-utilized and deteriorating. Producers depend only on middlemen and lack information about the specific quality demands of downstream actors. Sometimes they are trapped in credit-dependencies of buyers, and are forced to deliver the demanded quantities at any price.

NTFP Production is a Complementary Income Activity with Bridging and Substituting Characteristics

In some producers’ livelihoods strategies, the NTFP activities bridge seasonal income gaps. The main objective is not to maximize profits from the particular NTFP, but to ensure liquidity in a critical season of the year.

Results from the PIP Workshops

Pre-phase: Diagnostic Studies and Actors

As indicated in Fig. 1, the diagnostic surveys during the Pre-phase provided market information and generalized value chain maps, to enhance understanding and participative analysis during the PIP workshops. The maps show relevant actor groups as well as complexity and length of the studied chains. Figure 3 presents the gum Arabic chain, a global value chain dominated by export, and composed of an extensive network of middlemen.

In contrast to the gum Arabic chain, the extent of the Ethiopian bamboo chain (Fig. 4) is within the region only, with few actors, a single middleman linking production and processing.

The natural gums chain (Fig. 5) is influenced by tribal relations, which facilitates informal trade and cross-border smuggling of black incense and other oleo-gum resins.

The diagnostic survey was the first contact of the research team with value chain actors. The contact details of these actors were noted during the survey, and from this list, representatives for the PIP workshop were selected by the project team in a way that the PIP participants mirrored the chain structure in a balanced manner. The PIP workshop composition (Fig. 6) reflects the structure and length of each value chain. Specifically

-

the gum Arabic PIP was dominated by direct value chain actors, especially middlemen;

-

the bamboo PIP was dominated by supporters because several members of the university partner were involved in the diagnosis and had participated in the PIP workshop; and

-

the natural gums PIP had a small share of value chain regulators, because most of the line ministry agents perceived their mandate as extension service, not as supervisors.

Phase 1 of PIP Workshop: Diagnosis of Production and Marketing Systems

All PIPs were conducted by teams of five to ten researchers, coming from a national and an international research organization and a processing company. The PIP workshops started with the presentation of the diagnostic study results. In parallel, the map of the value chain (Figs. 3, 4, 5) was presented. The findings were discussed by the participants. Problems and opportunities were listed as those within an actor group and as those emerging between two groups. In general, the participants confirmed the researcher’s findings. Nevertheless, it was important for the participants to include their own perspectives and problems perceived. By this, the map was validated and a common understanding as well as a sense of ownership of the diagnosis results was created.

Phase 2 of PIP Workshop: Identification and Ranking of Critical Points and Opportunities

Phase 2 focused on a deeper analysis of each actor group along the value chain and their interfaces with neighboring ones. The workshop participants carried out this analysis, facilitated by the research teams. For the retrospective comparative analysis of the three PIP processes, the problems identified and solutions addressing these problems were categorized and coded.Footnote 1

Participatory analysis by participants was conducted in two rounds, first in groups per actor group and second with all participants together. Supported by a facilitator, the groups discussed and complemented the listing of problems, and ranked them pairwise, following the methodology described by Alemu and Auch (2016). The results for each actor group are summarized in Table 1, and those of the whole workshop in Table 2. The participants of the gum Arabic PIP skipped this phase and formed mixed groups to discuss extensively the bargaining power asymmetry between producers and middlemen. Their output was a list of recommended interventions (reported in Table 4).

Phase 3 of PIP Workshop: Innovative Upgrading Measures, Agreement on Action

Participants brainstormed upgrading ideas, based on problems and potentials of their chain. Table 3 summarizes the ranked upgrading ideas for each actor group. In the Natural Gums workshop, the supporters decided to join the producers for this session.

Most of the priority measures referred to categories of knowledge or marketing. For the identification of innovative pilot measures, the four highest ranked ideas from each group (Table 3) were considered. For eligibility, the ideas were checked against the following requirements: innovative technology transfer, availability of resources for implementation, the likelihood of success within project period, expected impact and sustainability.

Post-phase: Implementation of Upgrading Measures, Follow-Up Workshops

The implemented pilot measures (Table 4) focused on technological knowledge and skills. Funding of complex and long-term measures was beyond the project bounds.

Discussion

Comparative Analysis of the PIP Processes

All PIP processes were shaped by societal and cultural contexts. The gum Arabic workshop presented an opportunity for participants to negotiate the power imbalance between producer and exporter; an urgent problem overriding the scheduled sequence of methods for upgrading. Several of the less frequently prioritized problems raised by the Ethiopian PIPs also fall into the remit of the state, e.g. poor road conditions (INFR), degradation of open access forest resources, and smuggling (CORR). Constraints of technology (TECH) were more often prioritized in the bamboo value chain, and resources (RESU) in the natural gum value chain. This can be explained by the nature and constraints of the particular chains, or by a dominance of participants who purposely put this issue up, in anticipation of a supportive follow-up project. Amongst the prioritized problems across all actor groups of both Ethiopian chains (Tables 1, 3) knowledge (KNOW) and marketing (MARK) were identified most frequently. As a response to the demand for knowledge, several training sessions were held and support materials were developed, especially for producers. Interventions to address marketing have been beyond the project’s resources.

While all three PIP workshops presented a first meeting opportunity for actors across the whole chain to express their challenges and interests, the dynamics characterizing these fora differed. All three PIPs started with a heated discussion, dominated by reproaches against the competitors. In the course of the Ethiopian PIPs the participants followed the scheduled group work in actor groups with problem identification and ranking, then the identification of solutions with design of options for action. Several of the listed problems were formulated as absence of desired solutions, e.g. “lack of government attention”. The Sudanese process was done in mixed actor groups to negotiate their particular issues, then the participants concentrated on the way forward by discussing options for actions. This indicates first, that the analysis part of the PIP workshop (Phase 2 in Fig. 1), is a challenge for the participants. Problem analysis was intended to be done in a constructive, ‘power-free dialogue’ as suggested from Habermaas (1981), based on understanding the real interests of the competitors instead of prejudices and strategic rhetoric only. All PIPs struggled to really identify the problems and to carve out the problem’s roots; participants preferred to discuss solutions and recommendations. Second, a PIP might also serve as an arena for needed negotiations between actor groups. The different courses of the processes in Sudan and Ethiopia indicate that cultural and customary settings have to be considered.

Endogenous innovation was triggered by the Bamboo PIP. Participating farmers from Arbegona started to collect seeds from bamboo that was flowering and dying at that time. They put up a nursery to grow seedlings for regenerating their bamboo stands. The PIP inspired them to appreciate the potential of bamboo as a substitute for the increasing wood gap in their country; despite the current poor market setup, they conserved the genetic resource for the future.

In all three PIPs, participants expressed the strong wish to repeat the PIP workshops. This suggests the need to formalize and institutionalize the PIPs, establish a constitution for participation including procedural rules, and to give a clear mandate for conduction to an independent organization. The process equally require the services of skillful moderators, and a sustainable funding scheme.

Lessons Learned for NTFP Value Chains

The three PIPs constitute a unique, sector-wide learning experience for both actors and researchers. A number of insights for further development and research were gained. One request with highest priority was the one for government’s awareness and support. By this, the actors showed a pattern of passivity and subservience. This might have been a tactic to obtain some extra benefits, although the actors’ passivity might indicate that they were not fully aware of their own, active role and potential for innovation and upgrade.

NTFP actors need a platform for negotiation and conflict management; this was demonstrated in the gum Arabic case, where the PIP was dominated by the struggle between producers and buyers.

Actors are aware of the value and potential of the NTFPs, and of their essential role in local livelihood strategies, against the backdrop of the alarming degradation of the resource base. The PIP provided a lens for the recognition of several untapped sustainable management strategies. These untapped strategies require collective action with respect to building institutional structures and management capacities.

All three value chains lack an institutionalized system for grading of qualities. The sales in bulk with mixed grade products lead to the production of poor quality at knock-down prices. The absence of formalized grade classes limits not only diversified pricing, but also efficient product aggregation and specific price information. Most importantly, it is also a disincentive for producers to re-invest in efficient production and sustainable resource management.

Poor organizational and physical infrastructure in the “first miles” of the VC hamper the bundling of products for efficient sales. Conventionally, these services are delivered by middlemen, who aggregate and transport the products to central market places. Developing good business relations, fairer cost and profit distribution, and becoming also an intermediary for information about product quality are required future steps for middlemen. As an alternative to independent middlemen, collective action for product aggregation and marketing by cooperatives or producer associations was discussed regularly. Critical study is needed on whether such models would pay the transaction cost for cooperation in these rather marginal NTFP businesses.

Collection and provision of market information is usually done by public institutions. The established systems for agrarian products could be extended with the collection and reporting of prices for NTFP products on selected market places.

The function of NTFPs in the income portfolio of some producers was not for profit maximization in the first place, but rather for liquidity in times of stress. The terms of trade have to be evaluated in the context of the particular livelihood strategies. Unviable NTFP production might become feasible in combination with other activities, e.g. livestock herding and natural gum collection are complementary, both activities depend on dry forests, and are often carried out by women and youth.

Benefits and Limits of the PIP: A Critical Reflection

Experiences with the PIP instrument are encouraging; the actors appreciated the platform as relevant for the expression of their interests and for the discussion of common issues. Moreover, the building of trust and social connectedness between the actor groups was found to strengthen the whole value chain. The effectiveness of innovation platforms is confirmed by agricultural innovation platforms, especially for longer periods (> 3 years) (Davies et al. 2018). To facilitate social-learning based change, a regular repetition of the PIP is a recommended way forward to sustain the process of knowledge creation and “adaptive innovation management”: Sparrow and Traoré (2018) found that the number of platform meetings was correlated with the functionality of the platform. In summary, to cater for effective innovation and change processes, a PIP needs regular repeated meetings, e.g. annual or biennial.

To implement a PIP process with high-degree participation is a tough job. PIPs are demanding, and need resources for organization and logistics as well as competent persons for moderation and translation (Alemu and Auch 2016). Each value chain is individual; it requires expertise to design and conduct a PIP in a tailor-made, context-related and flexible form. Value chain actors are usually competitors. To balance particular interests in a PIP workshop, and to achieve agreements for joint benefit of the “value chain community”, a chairperson with a strong and accepted personality is needed. Chairing a platform workshop is more than facilitating interests; it requires “moderation” of highly dominant players who try to capture the platform for their particular interests. To prevent bias, a neutral institution, not having own stakes in the value chain, should have the mandate to conduct and host the PIP. There is also need for “change agents” or “innovation brokers” (Boogaard et al. 2013, p. 16), and “political entrepreneurs” (Dedeurwaerdere 2009, p. 206) as well as personalities with the motivation for innovation, creativity and skills to coordinate collective action. Building such competences and providing the environment for profiling personalities of “change agents” remain on the priority list of higher education institutions.

The results and process of a PIP will be shaped by the composition of participants. Initiators of a PIP face the question of how to identify the right persons for giving a mandate to represent the value chain, and to achieve beneficial results. The claim of the participants of the gum Arabic PIP to invite next time also the gum Arabic collecting pastoralists indicates the potential for take-over of responsibility for the PIP process by participants.

The challenge remains for actors to invest their own resources in agreed actions. As long as funding is provided from outside, the activities are welcomed, irrespective of their effectiveness. Davies et al. (2018) found that after phasing out the external funding, key members cease to participate, while funding of more than 2–3 years creates unsustainable dependencies. The proof of the viability of the PIP will be the engagement of actors on own cost, e.g. in shared funding models. This is especially relevant for long-term implementation of new technology. True empowerment of actors and sustainable innovation has to be endogenous, driven by benefit margins from the upgrading activities. Dedeurwaerdere (2009) underlined the importance of practical incentives for actors as well as a defined set of rules for engagement and sharing as important conditions for their exploration of options for innovations. Therefore, pre-studies have to ascertain if there is a real demand for upgrading from the actors’ side, and to also establish, through a cost–benefit assessment, if the upgrading investments would pay off.

In conclusion, the PIP is a useful instrument for conducting innovation and change processes. It provides a useful opportunity for all actors to identify options geared towards reducing transaction cost, while promoting innovations which are beneficial for participants in the whole value chain. For marginalized producers of forest products in the Tropics, the PIP facilitates learning, cooperation and collective action for market access and scale effects. The discourse in a PIP informs about the specific product requirements, which enables the respective adoption of the forest production system.

The PIP instrument draws on several sociological concepts (Pretzsch and Auch forthcoming). For its further development, theoretical backing and integration in the value chain upgrading context, concepts from action-oriented field research and theories have to be scrutinized and incorporated. Some of these include the dilemma structure of economic coordination problems between rational choice and common welfare (Kollock 1998; Aoki 2011), aspects of formality (de Soto 2013), institutions for collective action (Ostrom 1990), and the mandate question in open fora. Further studies are required to determine the sustainability and scale effects of PIP introduced processes.

Notes

Definition of codes: CORR: unfair competition—informal and corrupted market partners carrying out illegal practices; INFR: tedious transport—poor infrastructure, absence of all-year-round trafficable access roads; KNOW: unprofessional, uninformed actors—poor knowledge and poor skills for the business activity, and/or lack of sharing of experiences between members of an actor groups; MARK: ill-informed marketers—no access to attractive markets, lack of market information; POWE: overlooked actors—competences and power to organize the group successfully, to promote lobbing interests; PRIC: unprofitable sales—low selling price; QUAL: uniform bulk price—absence of formally established and adopted grading of products with diversified pricing; RESU: input constraints—lack of resources to acquire land or premises, purchase inputs or technology, includes finance liquidity; SUPP: abandoned actors—lack of support from government and NGOs; TECH: inefficient production and processing practices—lack of production technology, tools and equipment.

References

Achard F, Beuchle R, Mayaux P, Stibig H-J, Bodart C, Brink A et al (2014) Determination of tropical deforestation rates and related carbon losses from 1990 to 2010. Glob Change Biol 20(8):2540–2554. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12605

Alemu AA, Auch E (2016) Participative Innovation Platforms (PIP): guideline for analysis and development of commercial forest product value chains in Sudan and Ethiopia. https://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:14-qucosa-203964. Accessed 3 July 2016

Aoki M (2011) Institutions as cognitive media between strategic interactions and individual beliefs. J Econ Behav Organ 79:20–34

Belcher B, Ruíz-Pérez M, Achdiawan R (2005) Global patterns and trends in the use and management of commercial NTFPs: implications for livelihoods and conservation. World Dev Spec Issue Livelihoods For Conserv 33(9):1435–1452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.10.007

Boogaard BK, Schut M, Klerkx L, Leeuwis C, Duncan AJ, Cullen B (2013) Critical issues for reflection when designing and implementing research for development in innovation platforms. CIGAR report. Wageningen University and Research Centre, Wageningen. https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/35028. Accessed 26 Feb 2014

Darr D, Vidaurre M, Uibrig H, Lindner A, Auch E, Ackermann K (2014) The challenges facing forest-based rural development in the Tropics and subtropics. In: Pretzsch J, Darr D, Uibrig H, Auch E (eds) Forests and rural development. Springer, Berlin, pp 51–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-41404-6_3

Davies J, Maru Y, Hall A, Abdourhamane IK, Adegbidi A, Carberry P, Dorai K, Ennin SA, Etwire PM, McMillan L, Njoya A, Ouedraogo S, Traoré A, Traoré-Gué NJ, Watson I (2018) Understanding innovation platform effectiveness through experiences from West and Central Africa. Agric Syst 165:321–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2016.12.014

de Soto H (2013) The facts are in: the Arab Spring is a massive economic revolution. Ceres edition, Tunis. http://www.ild.org.pe/books/the-facts-are-in/the-facts-are-in-the-arab-spring-is-a-massive-economic-revolution. Accessed 1 Feb 2020

Dedeurwaerdere T (2009) Social learning as a basis for cooperative small-scale forest management. Small Scale For 8:193–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11842-009-9075-5

European Union (2018) Study on the feasibility of options to step up EU action to combat deforestation and forest degradation: final report. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/forests/studies_EUaction_deforestation_palm_oil.htm. Accessed 28 Nov 2018

FAO (2015) Global forest resources assessment 2015. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome. www.fao.org/3/a-i4793e.pdf. Accessed 3 Nov 2015

Frysch J (2014) Small-scale bamboo processing by craftsman in Hawassa, Bale Mountains, Ethiopia. B.Sc. thesis, Institute of International Forestry and Forest Products, Technische Universitaet Dresden, Dresden

Habermaas J (1981) Theorie des kommunikativen Handelns. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt/Main

Hansen MC, Potapov PV, Moore R, Hancher M, Turubanova SA, Tyukavina A, Thau D, Stehman SV, Goetz SJ, Loveland TR, Kommareddy A, Egorov A, Chini L, Justice CO, Townshend JRG (2013) High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science 342:850. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1244693

Katila P, Galloway G, Jong W, Pacheco P, Mery G (eds) (2014) Forests under pressure: local responses to global issues. International Union of Forest Research Organizations (IUFRO), Vantaa

Klebert K, Schrader E, Straub WG (2000) Winning group results, 2nd edn. Windmühle, Hamburg

Kollock P (1998) Social dilemmas: the anatomy of cooperation. Annu Rev Sociol 24:183–214

Nederlof ES, Wongtschowski M, van der Lee F (eds) (2011) Putting heads together: agricultural innovation platforms in practice. Bulletins of the Royal Tropical Institute 396. KIT Publishers, Amsterdam

Ostrom E (1990) Governing the commons. The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press, New York

Poschen P, Sievers M, Abtew A (2014) Creating rural employment and generating income in forest-based value chains. In: Pretzsch J, Darr D, Uibrig H, Auch E (eds) Forests and rural development. Springer, Berlin, pp 145–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-41404-6_6

Pretzsch J (2014) Paradigms of tropical forestry in rural development. In: Pretzsch J, Darr D, Uibrig H, Auch E (eds) Forests and rural development. Springer, Berlin, pp 7–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-41404-6_2

Pretzsch J, Auch E. Methodological lessons from research on rural innovation and adaptation: a plea for constructivist and action-oriented research approaches in forestry. Tropical forestry focus no. 2020/1. Institute for International Forestry and Forest Products. Technische Universitaet Dresden, Dresden. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bsz:14-qucosa2-345981 (forthcoming)

Pretzsch J, Darr D, Lindner A, Uibrig H, Auch E (2014) Introduction. In: Pretzsch J, Darr D, Uibrig H, Auch E (eds) Forests and rural development. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-41404-6_1

Sanyang S, Taonda SJ-B, Kuiseu J, Coulibaly N'T, Konaté L (2016) A paradigm shift in African agricultural research for development: the role of innovation platforms. Int J Agric Sustain 14:187–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2015.1070065

Sills E, Shanley P, Paumgarten F, de Beer J, Pierce A (2011) Evolving perspectives on none-timber forest products. In: Shackleton S, Shackleton C, Shanley P (eds) Non-timber forest products in the global context. Springer, Berlin, pp 23–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-17983-9_2

Sparrow AD, Traoré A (2018) Limits to the applicability of the innovation platform approach for agricultural development in West Africa: socio-economic factors constrain stakeholder engagement and confidence. Agric Syst 165:335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2017.05.014

Tarig EM, Pretzsch J, Hassan IAM, Alemu Abetew A, Auch E (2017) Implications of consecutive policy interventions and measures on comparative advantage and export of gum Arabic from Sudan. Am J Agric Sci 4:1–12

Ticktin T, Shackleton C (2011) Harvesting non-timber forest products sustainably: opportunities and challenges. In: Shackleton S, Shackleton C, Shanley P (eds) Non-timber forest products in the global context. Springer, Berlin, pp 149–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-17983-9_7

Weisse M, Dow Goldman E (2017) Global tree cover loss rose 51 percent in 2016. World Resources Institute. www.wri.org/print/54271. Accessed 20 July 2019

Weisse M, Dow Goldman E (2018) 2017 was the second-worst year on record for tropical tree cover loss. World Resources Institute. www.wri.org/print/63875. Accessed 20 July 2019

Williams BK (2011) Adaptive management of natural resources—framework and issues. J Environ Manag 92:1346–1353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.10.041

World Bank (2014) Community forestry and REDD+. World Bank. www.profor.info/knowledge/community-forestry-and-redd, Accessed 7 Oct 2014

Yousefpour R, Jacobsen JB, Thorsen BJ, Meilby H, Hanewinkel M, Oehler K (2012) A review of decision-making approaches to handle uncertainty and risk in adaptive forest management under climate change. Ann For Sci 69:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-011-0153-4

Acknowledgements

The research was conducted within the framework of the CHAINS project (CHAnces IN Sustainability—promoting natural-resource-based product chains in East Africa), under Project-ID 01DG13017 funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). We are grateful to Jude Kimengsi, Peter Poschen and the editors for their critique that contributed to the development of this paper.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Auch, E., Pretzsch, J. Participative Innovation Platforms (PIP) for Upgrading NTFP Value Chains in East Africa. Small-scale Forestry 19, 419–438 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11842-020-09442-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11842-020-09442-9