Abstract

Despite remarkable recent advances in transition-metal-catalyzed C(sp3)−C cross-coupling reactions, there remain challenging bond formations. One class of such reactions include the formation of tertiary-C(sp3)−C bonds, presumably due to unfavorable steric interactions and competing isomerizations of tertiary alkyl metal intermediates. Reported herein is a Ni-catalyzed migratory 3,3-difluoroallylation of unactivated alkyl bromides at remote tertiary centers. This approach enables the facile construction of otherwise difficult to prepare all-carbon quaternary centers. Key to the success of this transformation is an unusual remote functionalization via chain walking to the most sterically hindered tertiary C(sp3) center of the substrate. Preliminary mechanistic and radical trapping studies with primary alkyl bromides suggest a unique mode of tertiary C-radical generation through chain-walking followed by Ni–C bond homolysis. This strategy is complementary to the existing coupling protocols with tert-alkyl organometallic or -alkyl halide reagents, and it enables the expedient formation of quaternary centers from easily available starting materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transition-metal-catalyzed construction of all-carbon quaternary centers via tert-C(sp3)−C coupling reactions represents a significant synthetic challenge. Not only are severe steric effects encountered around the metal center in such coupling reactions, but competing isomerization pathways of alkylmetal intermediates often have low barriers1,2,3,4. Nevertheless, the development of cross-coupling protocols that make use of tertiary alkyl−M (M = Mg5,6,7,8,9, Zn10, B11, and Na12,13) reagents has aroused substantial interest from the synthetic community. While some advances have been achieved, restricted substrate scopes, together with the need to synthesize the organometallic reagents, has severely limited application of this strategy (Fig. 1a). In this regard, the direct functionalization of tert-alkyl electrophiles offers advantages from the perspective of practicality and step economy14,15,16,17. Of note, recent progress in the area of reductive coupling18,19,20 with organic halides and pseudohalides21,22,23,24,25 or alkenes26,27 have expanded classes of viable coupling partners. These studies provide complementary and efficient avenues to access structurally diverse three-dimensional scaffolds under mild reaction conditions (Fig. 1b). For example, the elegant work of Gong’s group showcases the generality of this strategy, allowing arylation, alkylation and allylation of tertiary alkyl halides through Ni-catalyzed reductive cross-electrophile couplings21,22,23,24. In addition to the above mentioned direct coupling manifolds, carbofunctionalization of 1,1-disubstituted or trisubstituted alkenes is gaining momentum (Fig. 1c)28,29,30,31,32. Representative examples in this vein include Shenvi’s hydroarylation/alkylation of unactivated alkenes through Fe/Ni or Mn/Ni co-catalysis29,30 and Brown’s diarylation and arylborylation of trisubstituted alkenes31,32. Although these methods enable access to tert-C–C linkages, development of strategically different approaches remain in high demand.

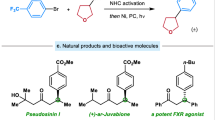

By exploiting iterative hydrometallation and β-hydride elimination, chain-walking enables the site-selective cross-coupling at positions remote to the initial metallation site33,34. Owing to the efforts of Sigman35,36,37, Marek38,39,40, Mazet41,42,43, Martín44,45,46,47, Zhu48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57, and others58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66, a collection of remote functionalizations, including arylation, alkylation, carboxylation, amination, borylation, and thiolation of unactivated alkenes or alkyl halides have been developed. Very recently, our team leveraged the fluorine-effect for a remote fluoro-alkenylation of unactivated alkyl bromides (Fig. 1d)67. Our system is like other remote functionalization reactions, where the driving force for chain-walking is moving the system lower on the energy landscape by positioning the metal center at a stabilizing position (usually limited to benzylic or alpha to boron). To expand the scope of remote functionalization reactions, alternative sites must be targeted, such as tertiary centers. With our continuing interest in remote functionalization, we have uncovered a mechanistically distinct and highly regioselective migratory 3,3-difluoroallylation68,69,70,71 of unactivated alkyl bromides at tertiary carbon centers. This undirected tert-C(sp3)−H functionalization nicely complements existing methods for all-carbon quaternary center construction, especially when tertiary alkyl halide/metal reagents are not readily available or not stable. Notably, during the preparation of this manuscript, Zhu and co-workers reported a relevant Ni–H-catalyzed migratory defluorinative olefin cross-coupling57.

Herein, we demonstrate that unactivated primary and secondary alkyl bromides are competent precursors for generating tertiary alkyl coupling partners via Ni–H-mediated chain-walking (Fig. 1e).

Results

Reaction optimization

A selection of alkyl halides was employed to react with α-trifluoromethylstyrene 2a. After initial screening, (bromomethyl)cyclohexane was successfully coupled with 2a at the tertiary position with good regioselectivity (>20:1) 64% assay yield in the presence of NiBr2·glyme, 6,6′-dimethyl-2,2′-bipyridine (L1) and Mn as terminal reductant (Table 1, entry 1, AY determined by integration of the 19F NMR spectrum against an internal standard). Given the pivotal role of ligands in Ni-catalyzed remote functionalizations, a series of bidentate N-donor ligands were examined to improve the reaction outcome. Substitution next to the nitrogens of the bipy ligands was found indispensable. Without either one or two methyl groups positioned ortho to the nitrogens, no product was observed. This observation is in accordance with previous reports (Supplementary Table 1)46,53,54. We hypothesized that increasing the steric bulk around the metal coordination site would enhance the reaction efficiency. Thus, a series of increasingly bulky substituents, such as ethyl, propyl, and butyl, were subsequently examined (entries 2–7). This study led to 6,6′-diethyl-2,2′-bipyridine (L2) as the top candidate, furnishing product 3a in improved yield and comparable regioselectivity (72% AY and >20:1 regioisomeric ratio, Table 1, entry 2). In addition, with pyrox or terpyridine ligands, essentially no reaction occurred (Table 1, entries 8 and 9). A solvent screen revealed that THF was the optimal choice (Table 1, entries 10–12), allowing the formation of the product in 89% isolated yield with >20:1 regioisomeric ratio. The influence of reductant was also examined. Mn proved superior to Zn, B2pin2, diethoxymethylsilane and HCOONa, which are commonly employed in reductive cross-coupling reactions (Supplementary Table 4).

3,3-Difluoroallylation of unactivated alkyl bromides

With the optimized reaction conditions in hand, the reaction scope of alkyl bromides was examined (Table 2). We found that a broad range of unactivated alkyl bromides were suitable substrates for the difluoroallylation. Cyclic alkyl bromides containing heteroatoms, such as oxygen and N-Boc, were well-tolerated, affording the 3,3-difluoroallylated products in 85 and 65% yields with excellent regioselectivities (3b and 3c). Notably, a cyclic acetal was tolerated to afford the desired product with good regioisomeric ratio, albeit in diminished yield (3d). Examination of the 5- and 7-membered carbocycles resulted in good regioselectivities (>11:1) with yields of 56 (3e) and 51% (3f) under the standard conditions. The lowered rr of 11:1 for 3e may be due to increased strain in the β-H elimination transition state. We were pleased to find that acyclic alkyl bromides provided products containing quaternary centers in 63–65% and high regioselectivities (>20:1, 3g–3i). Ester, ether, silyl ether, and phthalimide moieties were well tolerated, affording the corresponding 3,3-difluoroallylaion products in good yields (3j–3m). Interestingly, substrates containing two contiguous tertiary carbon centers only led to the migratory product at the proximal site (3n). Importantly, it was found that the migration could proceed over more than one C–C bond, albeit with progressively decreased reaction efficiency and regioisomeric ratio (3o, 47% yield with 7:1 rr and 3p, 31% yield with 2:1 rr). Nonetheless, these results highlight the selectivity of the present catalytic system toward tertiary carbon centers over secondary and primary positions. This trend is also observed in the formation of products 3q and 3r, where sec-alkyl bromides reacted ultimately giving predominantly coupling products at the tertiary site. The intramolecular competition revealed that the tertiary carbon was more favorable than 1° or 2° and even preferred over benzylic positions (3s). These findings stand in contrast to previous disclosures54. To further distinguish reactivity between secondary and primary sites, n-propyl and n-butyl bromide were examined (1t and 1u). It was found that coupling occurred more readily at the more congested secondary position (3t, 53% and rr >20:1; 3u, 28%, rr >20:1). It is noteworthy that chain-walking to more congested positions, in the absence of stabilizing groups, has not been previously realized.

It is interesting that the present reaction system can also be used to functionalize remote benzylic positions with high efficiency and selectivity (3v, 90% yield, >20:1 rr and 3w, 50% yield with 7:1 rr). Pleasingly, drug derived substrates performed well in the reaction (3x and 3y), demonstrating the synthetic potential of the difluoroallylation in late-stage modification of complex molecules. Furthermore, the diastereoselectivity of this transformation was assessed with enantioenriched substrate 1z, which delivered the migratory product 3z with 5:1 dr. Not unexpectedly, the optimized reaction conditions were applicable to the difluoroallylation of tertiary alkylbromide (3g from tert-BuBr). Finally, 1 mmol scale reaction was accomplished by using commercially available ligand (L1) with comparable efficiency, affording 3a in 65% yield with >20:1 rr.

Reaction scope with trifluoromethylalkenes

We next evaluated different trifluoromethylalkene substrates in this transformation (Table 3). Reactions carried out with α-trifluoromethylstyrenes bearing a wide range of functional groups on the aryl moiety, such as ester, ketone, cyanide, CF3, OCF3, sulfone, Me and OMe, all underwent coupling smoothly to afford the desired products in good yields (47–81%) and excellent selectivities (all > 20:1, 3aa–3ai). In addition, substrates containing Cl or F on the aryl were compatible with the transformation (3aj–3al, 51–78% yield, all >20:1 rr). Fortunately, heterocyclic trifluoromethyl alkene substrates (3am-3ap) were also well tolerated (45–80% yield, >20:1 rr).

Reaction scope with other activated olefins

To expand the scope of this transformation beyond trifluoromethylalkenes, other electron deficient olefins were examined. To our delight, acrylate, vinyl ketone, acrylonitrile, vinyl sulfone, and vinyl phosphonate derivatives were amenable under slightly modified reaction conditions. These substrates furnished migratory alkylation products in synthetically useful yields with excellent regioselectivities. These outcomes expand the synthetic reach of this tert-carbon-selective remote functionalization strategy, enabling the construction of quaternary carbon centers decorated with diverse functionality (Table 4).

To probe the mechanism of this migratory defluorinative allylation reaction, a set of control experiments were performed. To determine if chain-walking was indeed operating in the present system, the isotope-labelled substrate 1j-D was examined (Fig. 2a). As expected, the deuterium located at the tertiary carbon was selectively transferred to the primary position. This result strongly supports the involvement of chain-walking. It is notable that no deuterium was observed at other positions in the product. We hypothesized that radical intermediates may be involved and, therefore, conducted the reaction in the presence of TEMPO. The radical scavenger TEMPO suppressed the reaction and 97% of 2a remained, supporting the involvement of radical intermediates (Fig. 2b, eq 1). In addition, when 2a was replaced by allylic sulfone 6, allylation proceeded, suggesting the existence of 3 °C-radical intermediate under the catalytic conditions (Fig. 2b, eq 2). To further elucidate the mode of C–C bond formation, cyclic β-pinene-derivative (8) was subjected to the reaction (Fig. 2c). The observation of radical intermediates would be expected to result in ring-opened products, whereas a two-electron process would leave the ring intact. In the event, the resulting ring-opening product (9) was exclusively obtained. To explain the results in Fig. 2, we propose a tertiary carbon radical is generated and participates in the crucial C–C bond formation step72,73,74,75. The oxidative addition of alkyl bromides to low-valent Ni catalysts usually takes place through a cascade of single electron transfer and alkyl radical generating steps76. Such transformations, therefore, can be viewed as unusual radical center shifts that are mediated by transition metal catalysts. We believe the steric hindrance encountered at tert-C–Ni linkage is conducive to the homolytic rupture of the C–Ni bond, affording tertiary carbon-centered radicals that are a sufficiently long lived to escape the solvent cage and selectively react with trifluoromethylalkene derivatives.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that a radical-engaged chain-walking manifold is involved, which accounts for the unusual selectivity that leads to functionalization at the more congested tertiary position. A proposed mechanism is outlined in Fig. 3. The reaction is initiated by the oxidative addition of alkyl bromide 1 to active Ni complex I to afford intermediate II. Subsequently, chain-walking of the nickel catalyst from the terminal carbon to the tertiary center via β-hydride elimination and insertion steps allows for the facile generation of tert-C–Ni complex IV. The Ni–C to the tertiary carbon bond has the lowest BDE and undergoes homolysis, generating a tertiary C-radical V. The radical can undergo addition to the trifluoromethylalkene 2 to form a new radical species VI. The newly-formed radical intermediate then recombines with the nickel complex to give rise to intermediate VII, which undergoes β-fluoride elimination to produce the observed product 3, accompanied by the generation of F–Ni-complex VIII. Finally, reduction of Ni-complex VIII with Mn° closes the catalytic cycle by regenerating the active catalyst I. Whereas the radical manifold is consistent with the control experiments, the possible engagement of a 2-electron pathway relying on the direct addition of alkyl-Ni IV across the C–C double bond of 2, cannot be ruled out.

Discussion

In summary, a Ni-catalyzed reductive coupling for the synthesis of 1,1-difluoroalkenes containing quaternary centers is introduced. Difluoroalkenes are known bioisosteres for carbonyl groups in medicinal chemistry. The key to the success of this method is development of a Ni−H initiated remote functionalization of alkyl bromides. This approach enables a defluorinative 3,3-difluoroallylation of unactivated alkyl bromide substrates at sterically congested tertiary positions as an approach to selectively construct all-carbon quaternary centers. It is noteworthy that this transformation represents a rare case of C-radical transposition, which is enabled by a Ni−H chain-walking manifold. The successful development of this protocol demonstrates that readily available primary and secondary alkyl bromides can be used as progenitors for the construction of quaternary carbon-containing frameworks. In view of the potential impact of this strategy for remote functionalization, efforts to develop additional transformations are underway in these laboratories.

Methods

General procedure for the 3,3-difluoroallylation of unactivated alkylbromides

To an oven-dried Schlenk tube equipped with a magnetic stir bar was added NiBr2·glyme (3.1 mg, 0.01 mmol, 5.0 mol%), L2 (2.5 mg, 0.012 mmol, 6.0 mol%), Mn powder (16.5 mg, 0.3 mmol, 1.5 equiv). After the Schlenk tube was evacuated and filled with nitrogen for three cycles, THF (1.0 mL), compound 1 (0.6 mmol, 3.0 equiv) and compound 2 (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv) were added under nitrogen atmosphere. The Schlenk tube was maintained at 25 °C for 12 to 24 h. The reaction mixture was then diluted with ethyl acetate (10 mL) and washed with H2O (10 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (10 mL × 2). The combined organic layers were washed with water (10 mL), brine (10 mL) and dried over Na2SO4. After solvent was removed under reduced pressure, the crude residue was analyzed by 19F NMR with 1-iodo-4-(trifluoromethyl)benzene as internal standard, and then the mixture was purified by column chromatography or preparative TLC on silica gel to afford the desired product.

Data availability

The authors declare that all the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files, or from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Jana, R., Pathak, T. P. & Sigman, M. S. Advances in transition metal (Pd,Ni,Fe)-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions using alkyl-organometallics as reaction partners. Chem. Rev. 111, 1417–1492 (2011).

Choi, J. & Fu, G. C. Transition metal-catalyzed alkyl-alkyl bond formation: Another dimension in cross-coupling chemistry. Science 356, eaaf7230 (2017).

Lucas, E. L. & Jarvo, E. R. Stereospecific and stereoconvergent cross-couplings between alkyl electrophiles. Nat. Rev. Chem. 1, 0065 (2017).

Fu, G. C. Transition-metal catalysis of nucleophilic substitution reactions: a radical alternative to SN1 and SN2 processes. ACS Cent. Sci. 3, 692–700 (2017).

Terao, J., Todo, H., Begum, S. A., Kuniyasu, H. & Kambe, N. Copper-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of grignard reagents with primary-alkyl halides: remarkable effect of 1-phenylpropyne. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 2086–2089 (2007).

Ren, P., Stern, L.-A. & Hu, X. Copper-catalyzed cross-coupling of functionalized alkyl halides and tosylates with secondary and tertiary alkyl grignard reagents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 9110–9113 (2012).

Iwasaki, T., Takagawa, H., Singh, S. P., Kuniyasu, H. & Kambe, N. Co-catalyzed cross-coupling of alkyl halides with tertiary alkyl grignard reagents using a 1,3-butadiene additive. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 9604–9607 (2013).

Lohre, C., Drçge, T., Wang, C. & Glorius, F. Nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling of aryl bromides with tertiary grignard reagents utilizing donor-functionalized N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs). Chem. Eur. J. 17, 6052–6055 (2011).

Joshi-Pangu, A., Wang, C.-Y. & Biscoe, R. M. Nickel-catalyzed kumada cross-coupling reactions of tertiary alkylmagnesium halides and aryl bromides/triflates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 8478–8481 (2011).

Breit, B., Demel, P., Grauer, D. & Studte, C. Stereospecific and stereodivergent construction of tertiary and quaternary carbon centers through switchable directed/nondirected allylic substitution. Chem. Asian J. 1, 586–597 (2006).

Primer, D. N. & Molander, G. A. Enabling the cross-coupling of tertiary organoboron nucleophiles through radical-mediated alkyl transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 9847–9850 (2017).

Zhang, S., Kim, B.-S., Wu, C., Mao, J. & Walsh, P. J. Palladium-catalysed synthesis of triaryl(heteroaryl)methanes. Nat. Commun. 8, 14641–14648 (2017).

Zhang, S., Hu, B., Zheng, Z. & Walsh, P. J. Palladium-catalyzed triarylation of sp3 C–H bonds in heteroarylmethanes: synthesis of triaryl(heteroaryl)methanes. Adv. Syn. Catal. 360, 1493–1498 (2018).

Tsuji, T., Yorimitsu, H. & Oshima, K. Cobalt-catalyzed coupling reaction of alkyl halides with allylic grignard reagents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41, 4137–4139 (2002).

Zultanski, S. L. & Fu, G. C. Nickel-catalyzed carbon–carbon bond-forming reactions of unactivated tertiary alkyl halides: suzuki arylations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 624–627 (2013).

Zhou, Q., Cobb, K. M., Tan, T. & Watson, M. P. Stereospecific cross couplings to set benzylic, all-carbon quaternary stereocenters in high enantiopurity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 12057–12060 (2016).

Ariki, Z. T., Maekawa, Y., Nambo, M. & Crudden, C. M. Preparation of quaternary centers via nickel-catalyzed suzuki–miyaura cross-coupling of tertiary sulfones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 78–81 (2018).

Weix, D. J. Methods and mechanisms for cross-electrophile coupling of Csp2 halides with alkyl electrophiles. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 1767–1775 (2015).

Knappke, C. E. I. et al. Reductive cross-coupling reactions between two electrophiles. Chem. Eur. J. 20, 6828–6842 (2014).

Wang, X., Dai, Y. & Gong, H. Nickel-catalyzed reductive couplings. Top. Curr. Chem. 374, 43 (2016).

Wang, X., Wang, S., Xue, W. & Gong, H. Nickel-catalyzed reductive coupling of aryl bromides with tertiary alkyl halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 11562–11565 (2015).

Wang, X. et al. Ni-catalyzed reductive coupling of electron-rich aryl iodides with tertiary alkyl halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 14490–14497 (2018).

Chen, H., Jia, X., Yu, Y., Qian, Q. & Gong, H. Nickel-catalyzed reductive allylation of tertiary alkyl halides with allylic carbonates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 13103–13106 (2017).

Ye, Y., Chen, H., Sessler, J. L. & Gong, H. Zn-mediated fragmentation of tertiary alkyl oxalates enabling formation of alkylated and arylated quaternary carbon centers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 820–824 (2019).

Lu, X. et al. Nickel-catalyzed defluorinative reductive cross-coupling of gem-difluoroalkenes with unactivated secondary and tertiary alkyl halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 12632–12637 (2017).

Wang, Z., Yin, H. & Fu, G. C. Catalytic enantioconvergent coupling of secondary and tertiary electrophiles with olefins. Nature 563, 379–383 (2018).

Shu, W. et al. Ni-catalyzed reductive dicarbofunctionalization of nonactivated alkenes: scope and mechanistic insights. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 13812–13821 (2019).

Lo, J. C., Yabe, Y. & Baran, P. S. A practical and catalytic reductive olefin coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 1304–1307 (2014).

Green, S. A., Vasquez-Cespedes, S. & Shenvi, R. A. Iron–nickel dual-catalysis: a new engine for olefin functionalization and the formation of quaternary centers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 11317–11324 (2018).

Green, S. A., Huffman, T. R., McCourt, R. O., Puyl, V. & Shenvi, R. A. Hydroalkylation of olefins to form quaternary carbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 7709–7714 (2019).

Gao, P., Chen, L.-A. & Brown, M. K. Nickel-catalyzed stereoselective diarylation of alkenylarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 10653–10657 (2018).

Sardini, R. et al. Ni-catalyzed arylboration of unactivated alkenes: scope and mechanistic studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 9391–9400 (2019).

Sommer, H., Julia-Hernandez, F., Martin, R. & Marek, I. Walking Metals for Remote Functionalization. ACS Cent. Sci. 4, 153–165 (2018).

Vasseur, A., Bruffaerts, J. & Marek, I. Remote functionalization through alkene isomerization. Nat. Chem. 8, 209–219 (2016).

Liu, J., Yuan, Q., Toste, F. D. & Sigman, M. S. Enantioselective construction of remote tertiary carbon–fluorine bonds. Nat. Chem. 11, 710–715 (2019).

Mei, T.-S., Patel, H. H. & Sigman, M. S. Enantioselective construction of remote quaternary stereocentres. Nature 508, 340–344 (2014).

Werner, E. W., Mei, T.-S., Burckle, A. J. & Sigman, M. S. Enantioselective Heck arylations of acyclic alkenyl alcohols using a redox-relay strategy. Science 338, 1455–1458 (2012).

Sommer, H., Weissbrod, T. & Marek, I. A tandem iridium-catalyzed “Chain-Walking”/Cope rearrangement sequence. ACS Catal. 9, 2400–2406 (2019).

Ho, G.-M., Judkele, L., Bruffaerts, J. & Marek, I. Metal-catalyzed remote functionalization of ω-ene unsaturated ethers: towards functionalized vinyl species. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 8012–8016 (2018).

Masarwa, A. et al. Merging allylic carbon–hydrogen and selective carbon–carbon bond activation. Nature 505, 199–203 (2014).

Larionov, E., Lin, L., Guenee, L. & Mazet, C. Scope and mechanism in palladium-catalyzed isomerizations of highly substituted allylic, homoallylic, and alkenyl alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 16882–16894 (2014).

Lin, L., Romano, C. & Mazet, C. Palladium-catalyzed long-range deconjugative isomerization of highly substituted α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 10344–10350 (2016).

Romano, C. & Mazet, C. Multicatalytic stereoselective synthesis of highly substituted alkenes by sequential isomerization/cross-coupling reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 4743–4750 (2018).

Gaydou, M., Moragas, T., Julia-Hernandez, F. & Martín, R. Site-selective catalytic carboxylation of unsaturated hydrocarbons with CO2 and water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 12161–12164 (2107).

Sun, S.-Z., Borjesson, M., Martin-Montero, R. & Martín, R. Site-selective Ni-catalyzed reductive coupling of α-haloboranes with unactivated olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 12765–12769 (2018).

Juliá-Hernández, F., Moragas, T., Cornella, J. & Martín, R. Remote carboxylation of halogenated aliphatic hydrocarbons with carbon dioxide. Nature 545, 84–88 (2017).

Sun, S.-Z., Romano, C. & Martín, R. Site-selective catalytic deaminative alkylation of unactivated olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 16197–16201 (2019).

He, J., Song, P., Xu, X., Zhu, S. & Wang, Y. Migratory reductive acylation between alkyl halides or alkenes and alkyl carboxylic acids by nickel catalysis. ACS Catal. 9, 3253–3259 (2109).

Zhou, F., Zhu, J., Zhang, Y. & Zhu, S. NiH-catalyzed reductive relay hydroalkylation: a strategy for the remote C(sp3)−H alkylation of alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 4058–4062 (2018).

Zhou, F., Zhang, Y., Xu, X. & Zhu, S. NiH-catalyzed remote asymmetric hydroalkylation of alkenes with racemic α-bromo amides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 1754–1758 (2109).

Zhang, Y., Han, B. & Zhu, S. Rapid access to highly functionalized alkyl boronates by NiH-catalyzed remote hydroarylation of boron-containing alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 13860–13864 (2109).

Xiao, J., He, Y., Ye, F. & Zhu, S. Remote sp3 C–H amination of alkenes with nitroarenes. Chem 4, 1645–1657 (2108).

He, Y., Cai, Y. & Zhu, S. Mild and regioselective benzylic C–H functionalization: Ni-catalyzed reductive arylation of remote and proximal olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 1061–1064 (2017).

Chen, F. et al. Remote migratory cross-electrophile coupling and olefin hydroarylation reactions enabled by in situ generation of NiH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 13929–13935 (2017).

Zhang, Y., Xu, X. & Zhu, S. Nickel-catalysed selective migratory hydrothiolation of alkenes and alkynes with thiols. Nat. Commun. 10, 1752–1760 (2019).

He, Y., Liu, C., Yu, L. & Zhu, S. Ligand-enabled nickel-catalyzed redox-relay migratory hydroarylation of alkenes with arylborons. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 9186–9191 (2020).

Chen, F., Xu, X., He, Y., Huang, G. & Zhu, S. NiH-catalyzed migratory defluorinative olefin cross-coupling: trifluoromethyl-substituted alkenes as acceptor olefins to form gem-difluoroalkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 5398–5402 (2020).

Kumar, G. S. et al. Nickel-catalyzed chain-walking cross-electrophile coupling of alkyland aryl halides and olefin hydroarylation enabled by electrochemical reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 6513–6519 (2020).

Hu, M. & Ge, S. Versatile cobalt-catalyzed regioselective chain-walking double hydroboration of 1,n-dienes to access gem-bis(boryl)alkanes. Nat. Commun. 11, 765–774 (2020).

Kochi, T., Ichinose, K., Shigekane, M., Hamasaki, T. & Kakiuchi, F. Metal-catalyzed sequential formation of distant bonds in organic molecules: palladium-catalyzed hydrosilylation/cyclization of 1,n-dienes by chain walking. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 5261–5265 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Nickel-catalyzed 1,1-alkylboration of electronically unbiased terminal alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 8872–8876 (2019).

Bera, S. & Hu, X. Nickel-catalyzed regioselective hydroalkylation and hydroarylation of alkenyl boronic esters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 13854–13859 (2019).

Borah, A. J. & Shi, Z. Rhodium-catalyzed, remote terminal hydroarylation of activated olefins through a long-range deconjugative isomerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 6062–6066 (2108).

Chen, X., Cheng, Z., Guo, J. & Lu, Z. Asymmetric remote C-H borylation of internal alkenes via alkene isomerization. Nat. Commun. 9, 3939–3946 (2018).

Dupuy, S., Zhang, K.-F., Goutierre, A.-S. & Baudoin, O. Terminal-selective functionalization of alkyl chains by regioconvergent cross-coupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 14793–14797 (2016).

Li, J., S. Qu, S. & Zhao, W. Rhodium-catalyzed remote C(sp3)−H borylation of silyl enol ethers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 2360–2364 (2020).

Zhou, L., Zhu, C., Bi, P. & Feng, C. Ni-catalyzed migratory fluoro-alkenylation of unactivated alkyl bromides with gem-difluoroalkenes. Chem. Sci. 10, 1144–1149 (2019).

Ichitsuka, T., Takeshi Fujita, T. & Ichikawa, J. Nickel-catalyzed allylic C(sp3)−F bond activation of trifluoromethyl groups via β-fluorine elimination: synthesis of difluoro-1,4-dienes. ACS Catal. 5, 5947–5950 (2015).

Leriche, C., He, X., Chang, C.-W. & Liu, H.-W. Reversal of the apparent regiospecificity of NAD(P)H-dependent hydride transfer: the properties of the difluoromethylene group, a carbonyl mimic. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 6348–6349 (2003).

Zhu, C. et al. Selective C–F bond carboxylation of gem-difluoroalkenes with CO2 by photoredox/palladium dual catalysis. Chem. Sci. 10, 6721–6726 (2019).

Hu, J., Han, X., Yuan, Y. & Shi, Z. Stereoselective synthesis of Z fluoroalkenes through copper-catalyzed hydrodefluorination of gem-difluoroalkenes with water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 13342–13346 (2017).

Gutierrez, O., Tellis, J. C., Primer, D. N., Molander, G. A. & Kozlowski, M. C. Nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling of photoredox-generated radicals: uncovering a general manifold for stereoconvergence in nickel-catalyzed cross-couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 4896–4899 (2015).

Lan, Y., Yang, F. & Wang, C. Synthesis of gem-difluoroalkenes via nickel-catalyzed allylic defluorinative reductive cross-coupling. ACS Catal. 8, 9245–9251 (2018).

Lang, S. B., Wiles, R. J., Kelly, C. B. & Molander, G. A. Photoredox generation of carbon-centered radicals enables the construction of 1,1-difluoroalkene carbonyl mimics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 15073–15077 (2017).

Lu, X. et al. Nickel-catalyzed allylic defluorinative alkylation of trifluoromethyl alkenes with reductive decarboxylation of redox-active esters. Chem. Sci. 10, 809–814 (2019).

Diccianni, J. B. & Diao, T. Mechanisms of nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. Trends Chem. 1, 830–844 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21801131), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20170992), the “Thousand Talents Plan” Youth Program, and the “Jiangsu Specially-Appointed Professor Plan”. P.J.W. thanks the US National Science Foundation (CHE-1902509).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Z. and C.F. conceived and directed the project. Z-Y.L. performed the experiments. L.T., H.Z., and Y-F.Z. prepared some of the substrates. C.Z. and C.F. analyzed the results and wrote the paper. P.J.W. discussed the chemistry, suggested experiments and revised the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Stellios Arseniyadis and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, C., Liu, ZY., Tang, L. et al. Migratory functionalization of unactivated alkyl bromides for construction of all-carbon quaternary centers via transposed tert-C-radicals. Nat Commun 11, 4860 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18658-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18658-4

This article is cited by

-

Alkene 1,1-difunctionalizations via organometallic-radical relay

Nature Catalysis (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.