Abstract

We show that the algebraic boundaries of the regions of real binary forms with fixed typical rank are always unions of dual varieties to suitable coincident root loci.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Let \(f\in R_d={\mathbb {K}}[x,y]_d\) be a binary form of degree d, where \({\mathbb {K}}={\mathbb {R}}\) or \({\mathbb {C}}\). By definition, see e.g., [27], the \({\mathbb {K}}\)-rank of f is the minimum integer r such that f admits a decomposition \(f=\sum _{i=1}^r \alpha _i(\ell _i)^d\), where \(\alpha _i\in {\mathbb {K}}\) and \(\ell _i\in {{{\mathbb {K}}}[x,y]}_1\) for \(i=1,\ldots ,r\).

The \({\mathbb {C}}\)-rank of a form, also called complex Waring rank, has been widely studied by many authors. The case of binary forms was considered and completely solved by Sylvester [36], who proved that the generic rank, i.e., the complex rank of a general complex binary form of degree d, is \(\lceil \frac{d+1}{2}\rceil \) (see also [9]). The generic complex rank of forms in more variables is described by the celebrated Alexander–Hirschowitz theorem [1] (see also [3]).

On the other hand, the real Waring rank has been studied only in recent years and most of the questions are still open. Clearly the real case is particularly relevant for the applications. In fact, the notion of tensor rank, which generalizes the Waring rank, has recently attracted great interest in applied mathematics, chemometrics, complexity theory, signal processing, quantum information theory, machine learning, and other current fields of research; see e.g., [10, 11, 18, 25, 27, 28, 32, 33].

When we work on the real field, the notion of generic rank is replaced by the notion of typical ranks. A rank is called typical for real binary forms of degree d if it occurs in an open subset of \(R_d\), with respect to the Euclidean topology. More precisely, denoting by \({\mathcal {R}}_{d,r} \) the interior of the semi-algebraic set \(\{f\in R_d: \mathrm{{rk}}_{\mathbb {R}}(f)=r\}\) in the real vector space \(R_d\), a rank r is typical exactly when \({\mathcal {R}}_{d,r}\) is not empty. By [2] it is known that a rank r is typical for forms of degree d if and only if \(\frac{d+1}{2}\le r \le d\).

Let us now assume \(\frac{d+1}{2} \le r \le d\). Following [5, 29], we define the topological boundary \(\partial ({\mathcal {R}}_{d,r})\) as the set-theoretic difference of the closure of \({\mathcal {R}}_{d,r}\) and the interior of the closure of \({\mathcal {R}}_{d,r}\). Thus, if \(f\in \partial ({\mathcal {R}}_{d,r})\) then every neighborhood of f contains a generic form of real rank equal to r and also a generic form of real rank different from r. We have that \(\partial ({\mathcal {R}}_{d,r})\) is a semi-algebraic subset of \(R_d\) of pure codimension one. We define the algebraic boundary \(\partial _{\text {alg}}({\mathcal {R}}_{d,r})\), also called real rank boundary, as the Zariski closure of the topological boundary \(\partial ({\mathcal {R}}_{d,r})\) in the complex projective space \({\mathbb {P}}({\mathbb {C}}[x,y]_d)\).

The algebraic boundary for maximum rank \(r=d\) coincides with the discriminant hypersurface. Indeed by [6, 12], we know that the open set \(\mathcal R_{d,d}\) corresponds to the locus of real-rooted forms, that is forms with all distinct and real roots. In the opposite case, the algebraic boundary for minimum rank \(\overline{r}=\lceil \frac{d+1}{2}\rceil \) has been described in [29]. It is irreducible when d is odd, and it has two irreducible components when d is even. From these general results, it follows a complete description of all the algebraic boundaries with low degree \(d\le 6\).

In [5], we completely described the algebraic boundaries for the next two cases, \(d=7\) and \(d=8\). More precisely, we show in [5] that all the boundaries between two typical ranks are unions of dual varieties to suitable coincident root loci. Coincident root loci are well-studied varieties which parametrize binary forms with multiple roots, see Sect. 1.1 for the precise definitions.

In this paper, we study the algebraic boundaries for forms of arbitrary degree, and our main result is the following:

Theorem 0.1

(Theorems 3.2 and 3.3) For any degree d and any typical rank \(\frac{d+1}{2}\le r \le d\), the algebraic boundary \(\partial _{\text {alg}}({\mathcal {R}}_{d,r})\) is a union of dual varieties to coincident root loci.

Finally, we remark that the study of algebraic boundaries for forms with more than two variables is a challenging and quite open problem, see [30, 37].

The paper is organized as follows: In the preliminary Sect. 1, we recall some basic notions and results about coincident root loci, higher associated subvarieties and apolar maps. Section 2 is devoted to the detailed analysis of the pullbacks, via apolar maps, of higher associated varieties to coincident root loci. The main result of this section is Theorem 2.1, whose two corollaries (Corollaries 2.3 and 2.4) are key tools in the proof of Theorem 0.1. In Sect. 3, we prove Theorem 0.1: More precisely, we consider the case of odd degree in Theorem 3.2 and the case of even degree in Theorem 3.3.

2 Preliminary

2.1 Coincident Root Loci

Let r be a positive integer. A partition of r is an equivalence class, under reordering, of lists of positive integers \(\lambda =[\lambda _1,\ldots ,\lambda _n]\) such that \(\sum _{i=1}^n\lambda _i=r\). We denote by \(|\lambda |\) the length n of the partition. Alternatively, the partition \(\lambda \) can be represented by the list of integers \(m_1,\ldots , m_k\) defined as \(m_j=|\{i:\lambda _i=j\}|\), and clearly \(\sum _{j=1}^k jm_j=r\).

Given a partition \(\lambda \) as above, the coincident root locus \(\Delta _\lambda \subset {\mathbb {P}}^r = {\mathbb {P}}({\mathbb {C}}[x,y]_r)\) associated with \(\lambda \) is the set of binary forms f of degree r which admit a factorization \(f=\prod _{i=1}^n \ell _i^{\lambda _i}\) for some linear forms \(\ell _1,\ldots ,\ell _n\in {\mathbb {C}}[x,y]_1\). These varieties have been extensively studied, see e.g., [7, 8, 23, 26, 38].

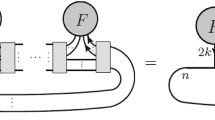

We have a unirational parameterization of degree \(m_1!m_2!\cdots m_k!\):

In particular, the dimension of \( \Delta _{\lambda }\) is n. The degree of \( \Delta _{\lambda }\) was determined by Hilbert [20]. He showed that

If \(\lambda \) and \(\mu \) are two partitions of r, we have \(\Delta _\mu \subseteq \Delta _\lambda \) if and only if \(\lambda \) is a refinement of \(\mu \) (equiv., \(\mu \) is a coarsening of \(\lambda \)). In [7] and subsequently in [26], it has been shown that the singular locus \(\mathrm{{Sing}}(\Delta _\lambda )\) is given by the union of \(\Delta _{\mu }\) for some suitable coarsenings \(\mu \) of \(\lambda \) (see [7, Definition 5.2] and [26, Proposition 2.1] for the precise description). In particular, one has that \(\Delta _\lambda \) is smooth if and only if \(\lambda _1=\cdots =\lambda _n\). Otherwise, the singular locus is of codimension 1.

The dual variety \((\Delta _\lambda )^\vee \) of \(\Delta _{\lambda }\subset {\mathbb {P}}({\mathbb {C}}[x,y]_r)\) is a subvariety of the projective space \({\mathbb {P}}({\mathbb {C}}[\partial _x,\partial _y]_r)\) of codimension \(m_1+1\) (see [23, Corollary 7.3]). In particular, \(\Delta _\lambda ^\vee \) is a hypersurface if and only if \(\lambda _i\ge 2\) for all i. In this case, its degree has been computed in [31, Theorem 1.4] and it is

Moreover, it is shown in [29, Corollary 2.6] that \((\Delta _\lambda )^\vee \subset {\mathbb {P}}({\mathbb {C}}[\partial _x,\partial _y]_r)\) is given by the join of the \(n-m_1\) coincident root loci \(\Delta _{(d-\lambda _i+2,1^{\lambda _i-2})}\) for \(1\le i\le n\) with \(\lambda _i\ge 2\).

2.2 Higher Associated Subvarieties

Let \({\mathbb {G}}(l,r)={\mathbb {G}}(l,{\mathbb {P}}^r)\) denote the Grassmannian of l-dimensional projective subspaces of \({\mathbb {P}}^r\). Let \( X\subset {\mathbb {P}}^r_{\mathbb C} \) be an irreducible projective variety of dimension n. Recall that the j-th higher associated variety \({{\,\mathrm{CH}\,}}_j(X)\) to X is the closure of the set of the \((r-n-1+j)\)-dimensional subspaces \(H\subset {\mathbb {P}}^r\) such that \(H\cap X\ne \emptyset \) and \(\dim (H\cap T_xX)\ge j\) for some smooth point \(x\in H\cap X\), see [14, Chapter 3, Section 1 E]. As it is known, \({{\,\mathrm{CH}\,}}_j(X)\) has codimension one in \({\mathbb {G}}(r-n-1+j,{\mathbb {P}}^r)\) if and only if \(0\le j\le \dim (X)-\mathrm {def}(X)\), where \(\mathrm {def}(X)\) denotes the dual defect of X (see [14, Chapter 3, Section 1 E] and [24, Corollary 6]). Recall also that, if j is an integer with \(0\le j\le n\), then the j-th polar degree of X, denoted by \(\delta _j(X)\), is the degree of \({{\,\mathrm{CH}\,}}_j(X)\) in \(\mathbb {G}(r-n-1+j,{\mathbb {P}}^r)\) if \({{\,\mathrm{CH}\,}}_j(X)\) is a hypersurface, while it is 0 otherwise (see e.g., [21], see also [24, Section 3]).

For our purpose, it is useful to consider a natural generalization of higher associated subvarieties, which we now introduce. For any integers j, l with \(0\le j\le l \le r\) and \(j\le n\), we define

Proposition 1.1

The scheme \({\mathbb {I}}_{j}^{l}\) is smooth and irreducible of dimension

that is

Proof

We have the following diagram of natural projections:

For each \(x\in X{\setminus } \mathrm {Sing}(X)\), we have \(q_1^{-1}(x)\simeq \{B\in {\mathbb {G}}(j,T_x X):x\in B\}\simeq {\mathbb {G}}(j-1,n-1)\). Thus, the projection \(q_1\) is a flat morphism with smooth fibers, and therefore, \({\mathbb {I}}_j^{j}\) is smooth and irreducible of dimension

If \((x,B)\in {\mathbb {I}}_j^j\), then \(\pi _1^{-1}(x,B) \simeq \{P\in {\mathbb {G}}(l,{\mathbb {P}}^r): B\subseteq P\}\simeq {\mathbb {G}}(l-j-1,r-j-1)\). Thus also the projection \(\pi _1\) is a flat morphism with smooth fibers, and it follows that \({\mathbb {I}}_j^l\) is smooth and irreducible of dimension

Hence the claim of the proposition follows. \(\square \)

Definition 1.2

Let \(\overline{{\mathbb {I}}_{j}^{l}} = \overline{{\mathbb {I}}_{j}^{l}(X)}\) be the closure of \({\mathbb {I}}_{j}^{l}\) inside \(X \times {\mathbb {G}}(j,{\mathbb {P}}^r)\times {\mathbb {G}}(l,{\mathbb {P}}^r)\), and denote by \(\pi _2:\overline{{\mathbb {I}}_{j}^{l}}\rightarrow {\mathbb {G}}(l,{\mathbb {P}}^r)\) the last projection. The scheme \(\pi _2(\overline{{\mathbb {I}}_{j}^{l}}) = \overline{\pi _2({\mathbb {I}}_{j}^{l})} \subset {\mathbb {G}}(l,{\mathbb {P}}^r)\) will be denoted by \(\Xi _{j}^{l}=\Xi _{j}^{l}(X)\).

Remark 1.3

The equations of the closure \(\overline{{\mathbb {I}}_{j}^{l}(X)}\) inside \(X \times {\mathbb {G}}(j,{\mathbb {P}}^r)\times {\mathbb {G}}(l,{\mathbb {P}}^r)\subset {\mathbb {P}}^r\times {\mathbb {P}}^{\left( {\begin{array}{c}r+1\\ j+1\end{array}}\right) -1} \times {\mathbb {P}}^{\left( {\begin{array}{c}r+1\\ l+1\end{array}}\right) -1} \), and hence, those of \(\Xi _{j}^{l}(X)\subset {\mathbb {P}}^r\) can be explicitly determined by standard elimination techniques, once one knows the equations of \(X\subset {\mathbb {P}}^r\). In particular, we point out that, if I denotes the homogeneous ideal of \(X\subset {\mathbb {P}}^r\), then the homogeneous ideal of \(\Xi _{j}^{l}(X)\subset \mathbb {G}(l,{\mathbb {P}}^r)\) can be calculated using the command tangentialChowForm(I,j,l), provided by the package Resultants [34] included with Macaulay2 [15].

Remark 1.4

It follows from the definition and Proposition 1.1 that we have

When \(j=0\) and \(l<r-n\), we have that \(\pi _2\) is birational onto its image. Indeed, if l is less than the codimension of X, then a generic l-dimensional projective subspace intersecting X meets X at only one point (see also the proof of [14, Chapter 3, Proposition 2.2]). Hence, when \(j=0\) and \(l<r-n\), the above inequality is an equality, that is

Example 1.5

If \(l = r-n-1+j\), then \(\Xi _j^l(X)={{\,\mathrm{CH}\,}}_j(X)\) is the j-th associated variety to X. In particular, we point out that \(\Xi _0^{r-n-1}(X)\) is the Chow hypersurface; if \(\deg (X)\ge 2\), then \(\Xi _1^{r-n}(X)\) is the Hurwitz hypersurface (see [35]); \(\Xi _n^{r-1}(X)\subset \mathbb {G}(r-1,{\mathbb {P}}^r)\) is the dual variety of X.

Example 1.6

Let \(\mathcal P\) be a complete flag in \({\mathbb {P}}^r\), that is, a nested sequence of projective subspaces \(\emptyset \subset P_0 \subset \cdots \subset P_{r-1}\subset P_{r}={\mathbb {P}}^r\) with \(\dim P_i = i\), and let \(a=(a_0,\ldots ,a_{l})\) be a sequence of integers with \(r-l\ge a_0\ge \cdots \ge a_l\ge 0\). Then the so-called Schubert variety \(\Sigma _a(\mathcal P)\subset {\mathbb {G}}(l,r)\) (see e.g., [16, Chapter 1, Section 5]) coincides with the following intersection:

2.3 Apolar Maps and Apolarity

Let \({\mathbb {K}}\subseteq {\mathbb {C}}\) be a field. Let \(R={\mathbb {K}}[x,y]\) be a polynomial ring and let \(D={\mathbb {K}}[\partial _x,\partial _y]\) be the dual ring of differential operators. The ring D acts on R with the usual rules of differentiations, and we have the pairing

If \(f = \sum _{i=0}^d \left( {\begin{array}{c}d\\ i\end{array}}\right) a_i x^{d-i} y^i\in R_d\), the apolar ideal \(f^{\perp }\subset D\) is given by all the operators which annihilate f, that is

For instance, if \(l=ax+by\in R_1\), then \(l^{\perp }\) is generated by the operator \(-b\partial _x + a\partial _y\in D_1\).

The component \((f^{\perp })_r = f^{\perp }\cap D_r\) is the kernel of the linear map \( D_r\rightarrow R_{d-r} \), which in the standard basis is represented by the catalecticant (or Hankel) matrix (up to multiplying the rows by scalars), see e.g., [13]:

For a general form \(f\in R_d\), with \(d \ge r\ge d-r\), the matrix \(A^{d,r}\) has maximal rank, and hence, \(\dim \mathrm {ker}(A^{d,r}) = 2r-d\). Thus we have a rational map, called the apolar map,

which associates to a general binary form f of degree d the projective \((2r-d-1)\)-dimensional subspace \( {\mathbb {P}}((f^\perp )_r)\subset {\mathbb {P}}(D_r)\). In coordinates, the map \(\varPsi _{d,r}\) is defined by the maximal minors of the matrix \(A^{d,r}\) thus by forms of degree \(d-r+1\). For \(d=r\), the map \(\varPsi _{d,d}\) gives an identification between \({\mathbb {P}}^d={\mathbb {P}}(R_d)\) and \({{\,\mathrm{\mathbb {G}}\,}}(d-1,d)={\mathbb {P}}(D_d)^{\vee }\).

Whenever \(r\ge \frac{d+2}{2}\), we have that \(\varPsi _{d,r}: {\mathbb {P}}^d\dashrightarrow {{\,\mathrm{\mathbb {G}}\,}}(2r-d-1,r)\) is a birational map onto its image. This implies that we can recover a general binary form of degree d from the component \((f^\perp )_r\subset f^{\perp }\). A more precise result is the following (see e.g., [22, Theorem 1.44], see also [2]).

Proposition 1.7

Assume that \(f\in R_d\) is not a power of a linear form. Then its apolar ideal \(f^\perp \) is generated by two forms \(g,g'\) such that \(d = \deg g+\deg g'-2\) and \(\mathrm {gcd}(g,g') = 1\). Conversely, any two such forms generate an ideal \(f^\perp \) for some projectively unique \(f\in R_d\).

We say that \(f\in R_d\) is generated in generic degrees if \((\deg g,\deg g') = (\lceil \frac{d+1}{2}\rceil ,\lfloor \frac{d+3}{2}\rfloor )\). The forms that are not generated in generic degrees form a subvariety of \(R_d\), which has codimension 1 if d is even and codimension 2 if d is odd. Indeed, this subvariety is defined by the maximal minors of the intermediate catalecticant matrix \(A^{d,\lfloor \frac{d+1}{2}\rfloor }\) of size \(\lceil \frac{d+1}{2}\rceil \times \lfloor \frac{d+3}{2}\rfloor \).

Let \(f\in R_d={\mathbb {K}}[x,y]_d\) be a binary form of degree d. A classical result is the following:

Lemma 1.8

(Apolarity Lemma) Assume \(f\in R_d\) and let \(\ell _i\in R_1\) be distinct linear forms for \(1\le i\le r\). There are coefficients \(\alpha _i\in {\mathbb {K}}\) such that \(f=\sum _{i=1}^r \alpha _i(\ell _i)^d\) if and only if the operator \(\ell _1^\perp \circ \cdots \circ \ell _r^\perp \) is in the apolar ideal \(f^\perp \).

It follows that a form f has rank less than or equal to r if and only if \((f^\perp )_r = f^\perp \cap D_r\) contains a form with all roots distinct and in \({\mathbb {K}}\). Recall that when \({\mathbb {K}}={\mathbb {R}}\), such a form is called real-rooted.

3 Pullbacks of Higher Associated Varieties to Coincident Root Loci

In this section, we study the geometry of the pullbacks, via apolar maps, of higher associated varieties to coincident root loci, \(\overline{\varPsi _{d,r}^{-1}({\mathrm {CH}}_j(\Delta _{\lambda }))}\). This analysis is a key tool in the description of the algebraic boundaries that we will carry out in Sect. 3, and we think it is interesting in itself.

Let r be a positive integer, and let \(\lambda =[\lambda _1,\ldots ,\lambda _n]\) be a partition of r of length \(|\lambda |=n\). Consider for any integer \(0\le j\le \min \{n,r-n-1\}\) the following set of partitions

and let us fix \(\lambda '\in {\mathcal {D}}_j(\lambda )\). Let \(\Delta _\lambda \subset {\mathbb {P}}^r\) (resp. \(\Delta _{\lambda '}\subset {\mathbb {P}}^{r-j}\)) be the coincident root locus corresponding to the partition \(\lambda \) (resp. \(\lambda '\)). Let \(d=r+n-j\) and consider the apolar maps:

We consider the j-th higher associated variety of \(\Delta _\lambda \subset {\mathbb {P}}^{r}\) (see Sect. 1.2),

which is a hypersurface if and only if \(j\le n-m_1(\lambda )\), where \(m_1(\lambda )\) is the number of 1 in the partition \(\lambda \). Set \(n'=|\lambda '|\le n\) and consider also the irreducible variety associated to \(\Delta _{\lambda '}\subset {\mathbb {P}}^{r-j}\) (see Definition 1.2 and Example 1.5),

By applying formula (1.4) of Remark 1.4, we compute that the codimension of \({\!{\Xi }}_0^{r{-}j{-}n{-}1}(\Delta _{\lambda '})\) in \({{\,\mathrm{\mathbb {G}}\,}}(r {-} j {-} n {-} 1{,}r{-}j)\) is

Theorem 2.1

Let notation be as above. Then the following formula holds set-theoretically:

Proof

We first show the inclusion \(\subseteq \). Let \(f\in {\varPsi _{d,r}^{-1}({\mathrm {CH}}_j(\Delta _\lambda ))}\). Then \( \varPsi _{d,r}(f) = (f^{\perp })_{r}\) contains a point \(h_0=\ell _1^{\lambda _1}\cdots \ell ^{\lambda _n}_n\in \Delta _\lambda \) such that \(L=T_{h_0}\Delta _\lambda \cap (f^\perp )_{r}\) is a projective linear space of dimension \(J\ge j\). Thus, there exist \(J+1\) linearly independent forms \(q_0,\ldots ,q_J\) of degree n such that

Consider now the form

which has degree \(d-(r-n) = (r+n-j)-(r-n) = 2 n - j \). Of course \(q_0,\ldots ,q_J\) annihilates p, yielding that the dimension of \((p^\perp )_n={\mathbb {P}}(\ker A_p^{2n-j,n})\) is at least J, where \(A_p^{2n-j,n}\) is the catalecticant matrix of p of size \((n-j+1)\times (n+1)\). This means that the rank of \(A_p^{2n-j,n}\) is at most \(n-J\).

Let us consider the catalecticant matrix \(A^{2n-j,n-J}_p\) of p of size \((n+(J-j)+1)\times (n-J+1)\). A well-known property of the catalecticant matrices (see e.g., [19, Proposition 9.7] or [22, Theorem 1.56]) implies that the ideals generated by the minors of order \(n-J+1\) of the generic catalecticant matrices \(A^{2n-j,n}\) and \(A^{2n-j,n-J}\) are the same (both define the \((n-J+1)\)-secant variety of the rational normal curve in \({\mathbb {P}}^{2n-j}\)). Thus, we deduce that the rank of \(A^{2n-j,n-J}_p\) is at most \(n-J\) as well and hence that there exists a form q of degree \(n-J\) in \((p^\perp )_{n-J}\). Let \(\tilde{q}=q\ell _1^{\lambda _1-1}\cdots \ell ^{\lambda _n-1}_n\), which of course belongs to \((f^\perp )_{r-J}\). From dimensional reasons, it follows that

and since \(h_0=\ell _1^{\lambda _1}\cdots \ell ^{\lambda _n}_n\in L\) we conclude that q divides \(\ell _1\cdots \ell _n\). Thus we have shown that there exists \(\tilde{\lambda }\in \mathcal {{D}}_J(\lambda )\) such that \(\tilde{q}\in \Delta _{\tilde{\lambda }}\). By multiplying \(\tilde{q}\) by \(J-j\) suitable forms among \(\{\ell _1,\ldots ,\ell _n\}\) we can find an element in \((f^{\perp })_{r-j}\cap \Delta _{\lambda '}\) with \(\lambda '\in \mathcal {{D}}_j(\lambda )\).

We now show the inclusion \(\supseteq \). Let \(\lambda '=(\lambda '_1,\ldots ,\lambda '_{n'})\in {\mathcal {D}}_j(\lambda )\), \({n'}\le n\), and \(f\in {\varPsi _{d,r-j}^{-1}({{\Xi }}_0^{r-j-n-1}(\Delta _{\lambda '}))}\). Then \(\psi _{d,r-j}(f) = (f^{\perp })_{r-j}\) intersects \( \Delta _{\lambda '}\) in a point q, say \(q=\ell _1^{\lambda '_1}\cdots \ell _{{n'}}^{\lambda '_{{n'}}}\). Let us consider the j-dimensional linear subspace

Clearly the intersection \(L\cap \Delta _{\lambda }\) is not empty and let \(\tilde{q} = \ell _1^{\lambda _1}\cdots \ell _n^{\lambda _n}\) denote one of its elements. (Notice that if all the \(\ell _i\) are distinct, then the cardinality of \(L\cap \Delta _{\lambda }\) is the number \(m(\lambda ',\lambda )\), defined in (2.9) below.) The tangent space \(T_{\tilde{q}}(\Delta _{\lambda })\) to \(\Delta _{\lambda }\) at the point \(\tilde{q}\) consists of the forms which are divisible by \(\ell _1^{\lambda _1-1}\cdots \ell _n^{\lambda _n-1}\). Hence \(T_{\tilde{q}}(\Delta _{\lambda })\) contains L, and it follows that \(\psi _{d,r}(f) = (f^{\perp })_{r}\in {{\,\mathrm{CH}\,}}_{j}(\Delta _{\lambda })\). This concludes the proof. \(\square \)

Remark 2.2

As a consequence of [29, Corollary 2.3], we have

where the last 1 occur \(n-n'\) times, and \({n'} = |\lambda '|\le n\). In particular, the variety in (2.4) has codimension 1 if and only if \(n'=n\). In this case, since \( \Xi _0^{r-j-n-1}(\Delta _{\lambda '}) = {\mathrm {CH}}_0(\Delta _{\lambda '})\) (see Example 1.5), we obtain

Corollary 2.3

Let notation be as above. We have

Proof

It follows from [23, Corollary 7.3] that the codimension of \((\!\Delta _{(\lambda '_1{+}1,{\ldots }{,}\lambda '_{n'}{+}1{,} 1{,}{\ldots }{,}1)})^{\vee }\) in \({\mathbb {P}}^d\) is \(n-{n'}{+}1\). Thus, by (2.4) and (2.2), we have

Therefore, from Theorem 2.1 we deduce that \(\overline{\varPsi _{d,r}^{-1}({\mathrm {CH}}_j(\Delta _{\lambda }))} \) has codimension 1 in \({\mathbb {P}}^d\) if and only if \(\mathcal D_j(\lambda )\) contains a partition \(\lambda '\) of length \(n'=n\), that is if and only if \(j\le n-m_1(\lambda )\). But this is exactly the condition for \({{\,\mathrm{CH}\,}}_j(\Delta _{\lambda })\) to be a hypersurface in \({{\,\mathrm{\mathbb {G}}\,}}(r - n - 1 + j,r)\). \(\square \)

For any integer \(0\le j\le n - m_1(\lambda )\), consider now the following subset of the set \({\mathcal {D}}_j(\lambda )\) defined in (2.1):

Then we have the following (see also Table 1):

Corollary 2.4

Let notation be as above. If \(j\le n - m_1(\lambda )\), then the following formula holds set-theoretically:

Proof

Since \(j\le n - m_1(\lambda )\), then the left-hand side of (2.3) is a hypersurface. Hence, we can exclude from the right-hand side all the components of codimension higher than 1. By Remark 2.2, this corresponds to ask that \(|\lambda '|=n\), and in this case we apply formula (2.5). \(\square \)

3.1 On the Multiplicities of the Components

Here, we try to give a more precise geometric description of the pullbacks, via apolar maps, of higher associated varieties to coincident root loci. In particular, we study the multiplicity of the components which appear in formula (2.3) of Theorem 2.1.

For any \(\lambda '=[\lambda '_1,\ldots ,\lambda '_{n'}]\in {\mathcal {D}}_j(\lambda )\) (see (2.1)), we define the multiplicity of \(\lambda \)’ with respect to \(\lambda \) as follows:

In particular, if \(\lambda '=[\lambda '_1,\ldots ,\lambda '_n]\in {\mathcal {F}}_j(\lambda )\) (see (2.7)), then the multiplicity is

Notice that the definition of \(m(\lambda ',\lambda )\) is motivated by the last part of the proof of Theorem 2.1.

Based on a number of experimental verifications (see Remark 2.7 and the examples below) and some general considerations on the singular loci of the higher associated varieties, we formulate here the following:

Conjecture 2.5

If \(j\le n - m_1(\lambda )\), then the following formula holds scheme-theoretically:

Remark 2.6

As an immediate consequence of Conjecture 2.5, together with the Oeding’s formula (1.1), we deduce an explicit formula for the polar degrees \(\delta _j(\Delta _{\lambda })\) of any coincident root locus \(\Delta _\lambda \) (see Sect. 1.2). In fact, if \(j> n - m_1(\lambda )\) (where \(n = |\lambda |\)) then \(\delta _j(\Delta _{\lambda }) = 0\); while if \(j\le n - m_1(\lambda )\) and since \(\psi _{d,r}\) is defined by forms of degree \(d-r+1=n-j+1\), then Conjecture 2.5 gives

where we denote by \(m_j(\lambda ')\) the number of j in the partition \(\lambda '\).

Remark 2.7

We have verified the validity of the Conjecture 2.5 for all partitions \(\lambda \) of \(r\le 7\). This has been done using the software Macaulay2 [15] with the packages CoincidentRootLoci [4] and Resultants [34]. We write out in Table 1 the explicit formulas for these partitions.

For the reader who wants to verify other cases, we also point out that the polar degrees of coincident root loci can be calculated using the aforementioned packages; for low dimensions \(r\le 7\), see also [29, 3rd col. of Table 1].

We illustrate the formula of Conjecture 2.5 with some examples.

Example 2.8

Let \(\lambda =(2,1^{n-1})\). Then \({\mathcal {F}}(\lambda )=\{(1^{n})\}\) and \(m((1^n),\lambda ) = n\). In this special case, Conjecture 2.5 gives a formula which was proved in [29, p. 514], that is

Example 2.9

Take the partition \(\lambda =(4,3,2,2)\) and \(j=1\), hence \(n=4\), \(r=11\), and \(d=14\). We have \({\mathcal {F}}_j(\lambda )=\{(4,3,2,1),(4,2,2,2),(3,3,2,2)\}\), with \(m((4,3,2,1),\lambda )=1\), \(m((4,2,2,2),\lambda )=3\), and \(m((3,3,2,2),\lambda )=2\). The apolar map \(\varPsi _{14,11} :{\mathbb {P}}^{14}\dashrightarrow {{\,\mathrm{\mathbb {G}}\,}}(7,11)\subset {\mathbb {P}}^{494}\) is defined by forms of degree 4, and the degree of the hypersurface \({\mathrm {CH}}_1(\Delta _{(4,3,2,2}))\) is 1740 (calculated with Macaulay2). From Corollary 2.4, it follows that \(\overline{\varPsi _{14,11}^{-1}({\mathrm {CH}}_1(\Delta _{(4,3,2,2)}))}\) has the following three components:

which have degrees, respectively, 2880, 640 and 1080. Conjecture 2.5 predicts that the first component occurs with multiplicity 1, the second one with multiplicity 3, and the last one with multiplicity 2. This is indeed the case, since we have \(1\cdot 2880 + 3\cdot 640 + 2\cdot 1080 = 4\cdot 1740\).

4 Algebraic Boundaries Among Typical Ranks for Binary Forms

Now, thanks to the results of the previous section, we are able to describe all the algebraic boundaries for binary forms of arbitrary degree d. We will consider the case of odd degree in Theorem 3.2, and the case of even degree in Theorem 3.3.

First, we state a preliminary result of differential topology, whose proof relies on the property of stability of transverse intersection, see [17, Chapter 2, Sections 5–6]. We sketch the proof for the reader’s convenience.

Lemma 3.1

If \(X\subset {\mathbb {P}}^N_{\mathbb {R}}\) is an irreducible variety of codimension c, and \(\varepsilon \in [0,1)\mapsto \Pi _{\varepsilon }\in \mathbb {G}(n,{\mathbb {P}}^N_{\mathbb {R}})\) is a one-parameter smooth family of n-dimensional linear subspaces such that \(\Pi _0\) meets X at a point p and \(\Pi _{\varepsilon }\cap X=\emptyset \) for each \(\varepsilon >0\), then we have \(\dim (T_p(X)\cap \Pi _{0}) \ge n - c + 1 \).

Proof

(Sketch of the proof) We can assume that p is a smooth point of X and that the dimension of the intersection \(\Pi _0\cap X\) at p is \(n-c\ge 0\), since otherwise the claim is trivial. Under these assumptions, we have to show that X and \(\Pi _0\) meet non-transversally at p, that is \(\dim \langle T_p(X) , \Pi _0\rangle < N\). If, by contradiction, they meet transversally at p, since the property to intersect transversally is stable under small deformations, we would have that also X and \(\Pi _{\varepsilon }\) meet transversally and \(X\cap \Pi _{\varepsilon }\ne \emptyset \), for any small \(\varepsilon >0\). \(\square \)

Theorem 3.2

If \(d = 2 k -1\) is odd, then the algebraic boundaries for degree d binary real forms satisfy the following:

-

(1)

If \(i=0\) then

$$\begin{aligned} \partial _{\text {alg}}({\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+i}) = (\Delta _{(3,2^{k-2})})^\vee . \end{aligned}$$ -

(2)

If \(1\le i\le k-2\) then

$$\begin{aligned} \partial _{\text {alg}}({\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+i}) \subseteq \bigcup _{\rho } (\Delta _{\rho })^{\vee } , \end{aligned}$$where \(\rho \) runs among the partitions of d with all parts greater than or equal to 2 and of length between \(k-1-i\) and \(k-1\); in particular,

$$\begin{aligned} \partial _{\text {alg}}({\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+1}) \subseteq (\Delta _{(3,2^{k-2})})^\vee \cup (\Delta _{(4,3,2^{k-4})})^\vee \cup (\Delta _{(5,2^{k-3})})^\vee \cup (\Delta _{(3,3,3,2^{k-5})})^\vee . \end{aligned}$$ -

(3)

If \(i = k-1\), then

$$\begin{aligned} \partial _{\text {alg}}({\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+i}) = (\Delta _{(d)})^\vee . \end{aligned}$$

Proof

Part (3) has been shown in [6], and part (1) is one of the results contained in [29]. Now we apply the idea, given in [29] and developed in [5], to study the boundary \(\partial _{\text {alg}}({\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+i})\) between \({\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+i}\) and \({\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+i+1}\cup \cdots \cup {\mathcal {R}}_{d,d}\), where \(1\le i\le k-2\).

Let \(\{f_{\varepsilon }\}_{\varepsilon }\) be a continuous (smooth) family of forms going from \({\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+i}\) to \({\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+i+1}\cup \cdots \cup {\mathcal {R}}_{d,d}\) and crossing some irreducible component of the boundary \(\partial _{\text {alg}}({\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+i})\) at a general point \(f_0=f\). Thus, we assume that \(f_{-\varepsilon }\in {\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+i}\) and \(f_\varepsilon \in {\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+i+1}\cup \cdots \cup {\mathcal {R}}_{d,d}\) for any small \(\varepsilon \) with \(\varepsilon >0\).

Let \({{\,\mathrm{\mathbb {G}}\,}}(2 i,k+i)\) be the Grassmannian of 2i-planes in \({\mathbb {P}}(D_{k+i})\), and consider the apolar map

which, since \(i\ge 1\), is a birational map onto its image \(Z_{d,k+i}\subset {\mathbb {P}}^{\left( {\begin{array}{c}k+i+1\\ 2 i +1\end{array}}\right) -1}\). The exceptional locus of \(\varPsi _{d,k+i}\) is contained in the locus of those forms whose annihilator is not generated in generic degrees, which has codimension 2 in \({\mathbb {P}}^d\). Therefore, we can assume that \(\varPsi _{d,k+i}\) is a local isomorphism at \(f_{\varepsilon }\) for each \(\varepsilon \), and hence, it sends bijectively the family \(\{f_\varepsilon \}_{\varepsilon }\) into a continuous family \(\{\Pi _{\varepsilon }\}_{\varepsilon }\) of apolar 2i-planes.

From the Apolarity Lemma (Lemma 1.8), we obtain that the 2i-plane \(\Pi _{\varepsilon }\), with \(\varepsilon <0\), contains a real-rooted form \(h_\varepsilon \), while \(\Pi _{\varepsilon }\), with \(\varepsilon >0\), does not contain any real-rooted form. The set of real-rooted forms is a full-dimensional connected semi-algebraic subset of \({\mathbb {P}}^{k+i}\), and the Zariski closure of its topological boundary is the discriminant hypersurface \(\Delta =\Delta _{(2,1^{k+i-2})}\). Recall also that the singular locus of a coincident root locus \(\Delta _\lambda \) is given by a union of \(\Delta _\mu \), for suitable coarsenings \(\mu \) of \(\lambda \). Thus we deduce that the limit \(h_0=\lim _{\varepsilon \rightarrow 0^{-}} h_{\varepsilon }\) must belong to \(\Delta \). More precisely, by applying Lemma 3.1, we obtain that there must exist \(a\in \{0,\ldots ,2 i\}\) such that \(h_0\) is a (smooth) point of a coincident root locus \(\Delta '\subseteq \Delta \subset {\mathbb {P}}^{k+i}\) corresponding to a partition \(\lambda \) of \(k+i\) of length \(k+i-a-1\) and the tangent space \(T_{h_0}(\Delta ')\) intersects \(\Pi _0\simeq {\mathbb {P}}^{2i}\) in a subspace H of dimension at least \(2i-a\) passing through \(h_0\). This implies that \(\Pi _0\in {{\,\mathrm{CH}\,}}_{2i - a}(\Delta ')\), so that \(f\in \overline{\varPsi _{d,k+i}^{-1}({{\,\mathrm{CH}\,}}_{2i - a}(\Delta '))}\).

Thus we have that each irreducible component of the boundary that separates \({\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+i}\) from \({\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+i+1}\cup \cdots \cup {\mathcal {R}}_{d,d}\) is contained in the following union

where \(\lambda \) runs among all the partitions of \(k+i\) of length \(k+i-a-1\), and where moreover \(\overline{\varPsi _{d,k+i}^{-1}({{\,\mathrm{CH}\,}}_{2i - a}(\Delta _{\lambda }))}\) is required to have codimension 1. By Corollary 2.3, this last condition is equivalent to the fact that \({{\,\mathrm{CH}\,}}_{2i - a}(\Delta _{\lambda })\) is a hypersurface in \({{\,\mathrm{\mathbb {G}}\,}}(2 i,k+i)\), that is such that \(2i-a\le k+i-a-1 - m_1(\lambda )\). Thus, by applying Corollary 2.4, we deduce that

where \(\mu \) runs among the partitions of \(k-i+a\) of length \(k+i-a-1\), \(\nu \) runs among the partitions of d of length \(k+i-a-1\) with parts \(\ge 2\), and \(\rho \) runs among the partitions of d of length between \(k-1-i\) and \(k-1+i\) with parts \(\ge 2\). Of course we must have \(a\ge i\) and the length of a partition \(\rho \) is at most \(k-1\).

Let

where \(\lambda \) runs among the partitions of d of length \(k-1-i\) and with all parts \(\ge 2\). We have shown that

Now, by an easy induction on i, we obtain

and we conclude the proof by taking the Zariski closure. \(\square \)

Theorem 3.3

If \(d = 2 k \) is even, then the algebraic boundaries for degree d binary real forms satisfy the following:

-

(1)

If \(i=1\) then

$$\begin{aligned} \partial _{\text {alg}}({\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+i}) = (\Delta _{(3^2,2^{k-3})})^\vee \cup (\Delta _{(4,2^{k-2})})^\vee . \end{aligned}$$ -

(2)

If \(2\le i\le k-1\) then

$$\begin{aligned} \partial _{\text {alg}}({\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+i}) \subseteq \bigcup _{\rho } (\Delta _{\rho })^{\vee }, \end{aligned}$$where \(\rho \) runs among the partitions of d with all parts greater than or equal to 2 and of length between \(k-i\) and k; in particular,

$$\begin{aligned} {\partial _{\text {alg}}({\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+2})}&\subseteq (\Delta _{(2^{k})})^\vee \cup (\Delta _{(3^2,2^{k-3})})^\vee \cup (\Delta _{(4,2^{k-2})})^\vee \cup (\Delta _{(6,2^{k-3})})^\vee \cup (\Delta _{(5,3,2^{k-4})})^\vee \\&\quad \cup (\Delta _{(4^2,2^{k-4})})^\vee \cup (\Delta _{(4,3^2,2^{k-5})})^\vee \cup (\Delta _{(3^4,2^{k-6})})^\vee . \end{aligned}$$ -

(3)

If \(i = k\), then

$$\begin{aligned} \partial _{\text {alg}}({\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+i}) = (\Delta _{(d)})^\vee . \end{aligned}$$

Proof

Thanks to [6, 29] we have only to show part (2). The proof for this part is quite similar to that of Theorem 3.2 and we now sketch it. Consider a continuous (smooth) family of degree d forms \(\{f_{\varepsilon }\}_{\varepsilon }\) such that \(f_{-\varepsilon }\in {\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+i}\) and \(f_\varepsilon \in {\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+i+1}\cup \cdots \cup {\mathcal {R}}_{d,d}\) for any small \(\varepsilon \) with \(\varepsilon >0\), and where we can also require that \(f_{\varepsilon }\notin (\Delta _{2^k})^{\vee }\). The birational map

has exceptional locus contained in the hypersurface \((\Delta _{2^k})^{\vee }\), so it sends bijectively the family \(\{f_\varepsilon \}_{\varepsilon }\) into a continuous family of apolar \((2i-1)\)-planes \(\{\Pi _{\varepsilon }\}_{\varepsilon }\). From Lemmas 1.8 and 3.1, we deduce that \(f=f_0\) must belong to the following union

where \(\lambda \) runs among all the partitions of \(k+i\) of length \(k+i-a-1\) and such that \(\overline{\varPsi _{d,k+i}^{-1}({{\,\mathrm{CH}\,}}_{2i - a -1}(\Delta _{\lambda }))}\) has codimension 1. Now we can conclude by applying Corollaries 2.3 and 2.4, as in the proof of Theorem 3.2. \(\square \)

Remark 3.4

If \(d=2k\le 8\), then the hypersurface \((\Delta _{(2^k)})^{\vee }\) does not belong to any boundary; see [5, 29]. We expect that the same holds in general.

Furthermore, notice that parts (2) of Theorems 3.2 and 3.3 are not sharp. Indeed for low degrees, \(d\le 8\), we know by [5] that the formula

holds with equality when we take only partitions with length \(\rho \in \{k-i-1, k-i\}\) if d is odd, and with length \(\rho \in \{k-i, k-i+1\}\) if d is even. We expect that the same happens in general. This also would imply that an algebraic boundary exists only between a region \({\mathcal {R}}_{d,r}\) and \({\mathcal {R}}_{d,r+1}\) (or \({\mathcal {R}}_{d,r-1}\)).

In Tables 2 and 3, we report the number of partitions of given length of some integers, in accordance to the formulas of Theorems 3.2 and 3.3. The sum of the elements of the k-th row up to position i gives an upper bound for the number of components of the algebraic boundary \(\partial _{\text {alg}}({\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+i})\), where \(d=2k-1\) if d is odd, and \(d=2k\) if d is even. However, by taking into account our expectations described in Remark 3.4, a finer upper bound for the number of components of \(\partial _{\text {alg}}({\mathcal {R}}_{d,k+i})\) would be given just by the sum of the two numbers in the k-th row corresponding to the position i and \(i-1\).

References

J. Alexander and A. Hirschowitz, Polynomial interpolation in several variables, J. Algebraic Geom. 4 (1995), no. 2, 201–222.

G. Blekherman, Typical real ranks of binary forms, Found. Comput. Math. 15 (2015), no. 3, 793–798.

M. C. Brambilla and G. Ottaviani, On the Alexander–Hirschowitz theorem, J. Pure Appl. Algebra 212 (2008), no. 5, 1229–1251.

M. C. Brambilla and G. Staglianò, CoincidentRootLoci: a macaulay2 package for computations with coincident root loci, version 0.1.2, online documentation and source code are available at https://faculty.math.illinois.edu/Macaulay2/doc/Macaulay2-1.15/share/doc/Macaulay2/CoincidentRootLoci/html, 2018.

M. C. Brambilla and G. Staglianò, On the algebraic boundaries among typical ranks for real binary forms, Linear Algebra Appl. 557 (2018), 403–418.

A. Causa and R. Re, On the maximum rank of a real binary form, Ann. Mat. Pura Appl. 190 (2011), no. 1, 55–59.

J. V. Chipalkatti, On equations defining coincident root loci, J. Algebra 267 (2003), no. 1, 246–271.

J. V. Chipalkatti, Invariant equations defining coincident root loci, Arch. Math. 83 (2004), no. 5, 422–428.

G. Comas and M. Seiguer, On the rank of a binary form, Found. Comput. Math. 11 (2010), no. 1, 65–78.

P. Comon, G. Golub, L.-H. Lim, and B. Mourrain, Symmetric tensors and symmetric tensor rank, SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 30 (2008), no. 3, 1254–1279.

P. Comon and B. Mourrain, Decomposition of quantics in sums of powers of linear forms, Signal Processing 53 (1996), no. 2, 93 – 107.

P. Comon and G. Ottaviani, On the typical rank of real binary forms, Linear Multilinear Algebra 60 (2012), no. 6, 657–667.

R. Ehrenborg and G.-C. Rota, Apolarity and canonical forms for homogeneous polynomials, European J. Combin. 14 (1993), no. 3, 157–181.

I. M. Gelfand, M. M. Kapranov, and A. V. Zelevinsky, Discriminants, resultants, and multidimensional determinants, reprint of the 1994 edition ed., Birkhäuser Boston, 2008.

D. R. Grayson and M. E. Stillman,Macaulay2– A software system for research in algebraic geometry (version 1.16), home page: http://www.math.uiuc.edu/Macaulay2/, 2020.

P. Griffiths and J. Harris, Principles of algebraic geometry, Pure Appl. Math., Wiley-Intersci., New York, 1978.

V. Guillemin and A. Pollack, Differential topology, American Mathematical Society, 2010.

W. Hackbusch, Tensor spaces and numerical tensor calculus, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012.

J. Harris, Algebraic geometry: A first course, Grad. Texts in Math., vol. 133, Springer-Verlag, New York, 1992.

D. Hilbert, Über die Singularitäten der Diskriminantenfläche, Math. Ann. 30 (1887), no. 4, 437–441.

A. Holme, The geometric and numerical properties of duality in projective algebraic geometry, Manuscripta Math. 61 (1988), no. 2, 145–162.

A. Iarrobino and V. Kanev, Power sums, Gorenstein algebras, and determinantal loci, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, vol. 1721, Springer-Verlag, 1999, with an Appendix by A. Iarrobino and S. L. Kleiman.

G. Katz, How tangents solve algebraic equations, or a remarkable geometry of discriminant varieties, Expo. Math. 21 (2003), no. 3, 219–261.

K. Kohn, Coisotropic hypersurfaces in Grassmannians, J. Symbolic Comput. (2019), in press, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsc.2019.12.002.

T. G. Kolda and B. W. Bader, Tensor decompositions and applications, SIAM Rev. 51 (2009), no. 3, 455–500.

S. Kurmann, Some remarks on equations defining coincident root loci, J. Algebra 352 (2012), no. 1, 223–231.

J. M. Landsberg, Tensors: geometry and applications, vol. 128, American Mathematical Soc., 2012.

J. M. Landsberg and G. Ottaviani, New lower bounds for the border rank of matrix multiplication, Theory Comput. 11 (2015), no. 11, 285–298.

H. Lee and B. Sturmfels, Duality of multiple root loci, J. Algebra 446 (2016), 499–526.

M. Michałek, H. Moon, B. Sturmfels, and E. Ventura, Real rank geometry of ternary forms, Ann. Mat. Pura Appl. 196 (2017), no. 3, 1025–1054.

L. Oeding, Hyperdeterminants of polynomials, Adv. Math. 231 (2012), no. 3, 1308–1326.

L. Qi, W. Sun, and Y. Wang, Numerical multilinear algebra and its applications, Front. Math. China 2 (2007), no. 4, 501–526.

A. Smilde, R. Bro, and P. Geladi, Multi-way analysis with applications in the chemical sciences, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2004.

G. Staglianò, A package for computations with classical resultants, J. Softw. Alg. Geom. 8 (2018), no. 1, 21–30.

B. Sturmfels, The Hurwitz form of a projective variety, J. Symbolic Comput. 79 (2017), 186–196.

J. J. Sylvester, An essay on canonical forms, supplement to a sketch of a memoir on elimination, transformation and canonical forms, 1851, Paper 34 in vol. 1 (publ. 1904), pp. 203–216.

E. Ventura, Real rank boundaries and loci of forms, Linear and Multilinear Algebra 67 (2019), no. 7, 1404–1419.

J. Weyman, The equations of strata for binary forms, J. Algebra 122 (1989), no. 1, 244–249.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università Politecnica delle Marche within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Peter Bürgisser.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The first named author is partially supported by MIUR and INDAM.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brambilla, M.C., Staglianò, G. Algebraic Boundaries Among Typical Ranks for Real Binary Forms of Arbitrary Degree. Found Comput Math 21, 1003–1022 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10208-020-09474-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10208-020-09474-9

Keywords

- Typical rank

- Real rank boundary

- Algebraic boundary

- Binary form

- Multiple root locus

- Coincident root locus

- Waring problem