Abstract

From March to May 2020, the Italian health care system, as many others, was almost entirely devoted to the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic. In this context, a number of questions arose, from the increased stroke risk due to COVID-19 infection to the quality of stroke patient care. The overwhelming need of COVID-19 patient management made mandatory a complete re-organization of the stroke pathways: many health professionals were reallocated and a number of stroke units was turned into COVID-19 wards. As a result, acute stroke care suffered from a shortage of services and delays in time-dependent treatments and diagnostic work-up. In-patient and out-patient care and rehabilitation facilities for stroke survivors were also reduced or slowed down, to direct resources to COVID-19 patients care and to reduce contagion risks. Overall, this is likely to result in a significant future increased burden of complications and disabilities that will impact the health care systems in the coming months. Thus, while still fighting against COVID-19 disease, authorities need to promptly implement robust action plans, including an increase of workforce, without forgetting the assurance of a high level of stroke care. The medical community and the health care administrators should always keep in mind that stroke was before, and will be after the pandemic, a, sometimes, life-threatening condition, and almost always a disease with a severe impact on the quality of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV2) is affecting more than 24,200,000 million patients worldwide and has impacted health worldwide on an unprecedented scale. Italy is one of the most impacted countries with more than 262,500 cases and 35,548 deaths, the Lombardia region representing the most severely hit region [1]. From March throughout May 2020, the Italian health care system was almost entirely devoted to fight against SARS-CoV2 [2, 3]. Strategies for resource allocation, mobilizing workforce, and optimizing bed availability were rapidly implemented to face the increasing needs for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) patient care [4, 5]. This huge change in the landscape of healthcare delivery affected particularly the care of remaining severe and disabling diseases such as stroke. The engagement of stroke services and the shortage of health personnel resources, engaged in COVID-19 patient care, impaired not only the delivery of time-dependent treatments and of optimal diagnostic work ups in the acute phase but also the periodic follow-up of stroke survivors [4, 6]. Moreover, in the same time, stroke physicians had to monitor and protect stroke patients from the infection since cerebrovascular diseases, that may also occur as complications of SARS-CoV2 disease, were associated with more severe disease illness [7,8,9].

In this paper, we discuss the main direct and indirect impacts of COVID-19 on stroke care in Italy. Although the trend of infection is slowing in most countries, these issues are important because the next future is uncertain and we need to be prepared to both the so-called ‘phase two’ and to possible new pandemic spikes.

COVID-19 and cerebrovascular diseases

SARS-CoV2, similarly to other human coronaviruses, is known to spread from the respiratory tract to the central nervous system (CNS) through transneuronal and hematogenous routes, resulting in possible neurological complications [10,11,12,13]. Researchers from Beijing Ditan Hospital, China, first described a patient with COVID-19 in whom virus RNA was detected in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) by gene sequencing [14], raising the question of whether the virus can affect directly the nervous system. Neurological symptoms such as consciousness disturbance, headache, dizziness, hypogeusia, hyposmia, seizures and also ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes are increasingly observed in SARS-CoV2 patients [15, 16]. A recent study on 214 Chinese COVID-19 patients reported acute cerebrovascular events in 5.7% (four ischemic and one hemorrhagic) [15]. Stroke in association with COVID-19 infection occurs usually about 8–24 days after infection onset and is caused predominantly by large vessel occlusions [17]. Patients are usually older, with more cardiovascular comorbidities and more severe pneumonia [15].

However, since conclusive studies are lacking, the causal relationship between SARS-CoV2 and cerebrovascular disease is unclear. Although most of strokes in COVID-19 patients are classified as cryptogenic [18, 19], several pathophysiological mechanisms have been put forward. First, COVID-19, similarly to other infectious diseases, could increase the risk of cerebrovascular events [12, 15]. Second, COVID-19 patients were found to have thrombocytopenia, increased D-dimer, and C-reactive protein levels in comparison to non-COVID patients, indicative of coagulation cascade and inflammatory pathway activation, making these patients more likely to develop cerebrovascular diseases [15]. Thrombotic complications, including disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), were identified in patients affected by COVID-19 [20,21,22,23]. Third, the high frequency of cardiovascular complications due to SARS-CoV2 virus cardiac tropism may be responsible for a proportion of embolic strokes [22,23,24]. At this purpose, a considerable proportion of strokes met the criteria of embolic stroke of undetermined source [18, 19].

Last, studies showed that SARS-CoV-2 invades human respiratory epithelial cells through its S-proteins and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors on human cells surface [7, 25]. The expression and function of ACE2 receptor, normally reduced in hypertensive patients, is further reduced during SARS-CoV2 infection leading to a lower ability on controlling blood pressure [26]. Whether ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptors blockers are additional risk factors for infection and mortality is still unknown. Of note, given the lack of clinical evidence, the European Society of Cardiology strongly discourages anti-hypertensive therapy discontinuation, in consideration of the severe possible implications of these drugs withdrawn [26,27,28]. Which one of the above listed aspects is more relevant to explain stroke pathogenesis in SARS-CoV2 needs to be assessed by future research and retrospective analyses.

Acute stroke management and organization during COVID-19 pandemic

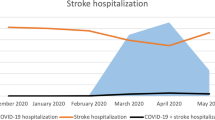

The COVID-19 crisis induced a huge reorganization of Italian health care system, particularly in some regions, which in Italy have considerable autonomy in health decision-making from the central government [3, 4, 29]. The Lombardia region, that had to deal with a rapid spreading of infection from the end of February 2020 [29,30,31], rearranged completely the frontline responders’ organization and resources according to the needs of health personnel and beds required for COVID-19 patients. Procedural algorithms and emergency medical system teams were rapidly implemented to handle the huge COVID-19 patient hospital flows and the emergency department overcrowding [5, 31, 32]. In this scenario, authorities had to deal with the organization of non-communicable diseases care, including stroke. In Lombardia and in other Italian regions, new stroke pathways have been established pointing to the centralization of care in a limited number of centers due to the stroke unit closure and reallocation of health professionals to COVID-19 wards [4, 33]. Dedicated stroke triage protocols, including the adequate screening of symptoms and signs of COVID-19 infection, isolation of patients in protected areas, and specific pathways for acute stroke treatments were activated according to regional indications [33, 34].

However, the number of hospitalized stroke patients and the amount of acute phase treatments such as thrombectomy was observed to be heavily reduced for several, and still not clarified, reasons [33,34,35]. The most reliable hypothesis is that the general population, and particularly elderly or hypertensive, diabetic, cardiopathic or disabled patients, because of the higher infection risk and mortality rate reported by media in these populations, were discouraged by family doctors and emergency operators to go to the hospital [33,34,35,36]. Hence, the care of people with non-COVID conditions such as stroke, who may have needed urgent care, was deferred or even completely not received [37, 38]. Another possibility is that stroke could be misdiagnosed in patients with COVID-19 respiratory symptoms [39], also because of limited and mask-impaired face to face visits or shortage of physicians and neuroradiological services. A further possible explanation is that in areas with high COVID-19 incidence stroke and COVID-19 might have competed for the same host and, thus, old subjects might have died of COVID-19 instead of having a stroke.

Also the activity of services for outpatients who survived a stroke or have chronic cerebrovascular diseases was highly slowed down and guaranteed only for urgent situations [4, 9, 29, 40]. This might have resulted in a deficient follow-up of patient complications missing verification of adherence to therapy and secondary prevention measures. These changes in stroke management, consequent to COVID-19 care prioritization, could have exposed patients to an increased risk of recurrent events or complication and to develop disabling condition, given the lack of correct management measures and diagnostic work ups [4, 9, 36,37,38].

COVID-19 screening and protection measures

Given the huge SARS-CoV-2 infection spreading, stroke patients presenting to emergency rooms necessitate accurate screening procedures started by paramedics at triage and completed by physicians. They should include a screening for a history of infection, travels or infected subject contacts. Since current data suggest that the SARS-CoV-2 virus may manifest not only with a constellation of symptoms including respiratory but also ophtalmologic, gastroenteric, and neurologic manifestations, control screen should include every kind of disease feature [41].

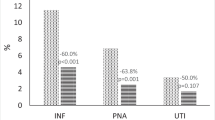

Patients other than being investigated as possible virus carriers should be also protected against contagion [42]. Particularly, contagion should be minimized in fragile subjects as stroke survivors because they are at increased risk for complications from SARS-Cov-2 infection. In fact, COVID-19 patients with preexisting cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases were observed to have 2.5-fold higher risk to develop a severe form of the illness or worse outcomes [8, 9]. To prevent contagion, several hospitals were divided into COVID + and COVID- and specific pathways and triage areas for COVID and non-COVID patients were created [33].

Health professionals are also at high risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection, so personal protective equipment (PPE) is extremely needed. Data from China’s National Health Commission showed that more than 3300 health-care workers have been infected. In Italy at least 20% of health-care workers were infected, and many have died [2]. Unfortunately, given the unforeseen pandemic spreading, Italian hospitals and also health professionals suffered from PPE shortages. Some medical staff was waiting for equipment while already seeing patients who were infected or supplied with equipment that did not meet requirements [43].

Another concern was as regards nasopharyngeal swabs and, more recently, serum antibody screening. Different screening strategies were adopted depending on countries. In Italy, given the rapidity of the infection spreading, indications from heath authorities changed overtime, following WHO indications. The initial guidelines recommended not to test the asymptomatic healthcare workers who have known exposures, or other asymptomatic individuals concerning exposures and/or travel history or poor symptomatic subjects [43]. The screening protocols changed over time to limit the virus spreading. In Italy, final indications included the systematic screening of all hospitalized patients as soon as they arrive to emergency room and each health professional who had been in contact with positive cases [43]. More recently, some hospitals are also equipping with antibody detection kits, to screen health workers for immunity.

COVID-19 inequalities and psychological implications

SARS-CoV-2 infected people and impacted lives in a not uniform way [45]. Disparities in socioeconomic status are well known to impact not only the stroke risk but also post-stroke short- and long-term outcomes [46]. The higher frequency of conventional risk factors (e.g., hypertension, hyperlipidemia, excessive alcohol intake, smoking, obesity, and sedentary lifestyle) and the lower access to good quality hospitals and rehabilitation services, in comparison with people with higher socioeconomic status, was observed to mostly account for the increased risk of stroke and disabilities on patients with low socioeconomic status [47]. This risk is expected to be further increased under condition of economic crisis as in COVID-19 outbreak [45]. Early reports described increased severity of COVID-19 infection in African Americans in USA [48].

Psychological aspects due to COVID-19 infection are also another important concern for both patients and health-care workers. Italian hospitalized stroke patients were worried of contagion, suffered from isolation, and had to deal with their own illness alone since communication with relatives was heavily reduced and often limited to short phone calls. Stroke survivors, who were left at home, suffered from the fear of being infected and from isolation since relatives were not allowed to meet them, due to social distancing measures. Also health care workers faced physical and mental exhaustion since they were placing their lives at risk, overworked to supply the lack of infected peers, who were at home in quarantine, and had to deal with difficult and tormented triage decisions [2, 49, 50]. Health professionals working in COVID + wards were also often isolated from their own families, elderly parents or young children, and were worried about the question of who was taking care of them. The shortage of testing, masks, other personal protective equipment medications critical for the management of COVID-19 were also other important stress causes [51].

Overall, these conditions may have resulted in health worker burnouts, with adverse consequences for patients, physicians, their families, and society. For this reason, some programs of psychological support for distress were implemented.

Stroke research and education

It is reasonable that in COVID-19 crisis time stroke scientific research may be drastically cut. In this pandemic, most research labs have been shut down to limit infection risk and to protect workers, making research personnel unable to complete their work [52]. This led to slowed work in performing additional experiments to complete studies delaying their publication by months or more. Several journals are continuing to publish papers, suffering in most cases for the lack of systemic data collection due to the challenging time. Also grant application may face difficulties for the lack of preliminary data and because most grants are devoted to COVID 19 research [19, 53], limiting possible discoveries in pathophysiology and treatment of cerebrovascular diseases.

Research activity programs, specific education courses, and guideline development were also drastically slowed while many ongoing clinical trials were stopped or heavily slowed down, due to the considerable diversion of personnel and funding towards COVID-19 research, thus slowing progresses in stroke care and management. National and international conferences, allowing science exchange and the implementation of large collaborations and studies were also suspended. The web and online replacement of these events may only partially overcome this, highly limiting human relationship and networking [54].Training and teaching activities were also markedly reduced, replaced by online sessions, with medical students obliged to stay home and many neurology residents turned to the care of COVID-19 patients [55].

Conclusions

The COVID-19 outbreak obviously drove most of health personnel and resources to COVID-19 care. The radical transformation of the health care system and the huge resource diversion to fight the spreading infection affected our ability to maintain the high quality of stroke as other non-communicable disease care. Italian regional authorities and stroke unit managers tried to cope with the continuously updated directives and led their teams to adapt to new hospital entry pathways and management recommendations. Stroke unit re-organization, emergency pathways and services engagement, and delayed emergency transportations limited patients to the possibility of undergoing acute phase treatments and correct diagnostic work ups [4, 33]. Moreover, for a number of reasons including fear of contagion or severe illness complications due to COVID-19 infection, a number of patients with acute cerebrovascular diseases remained home, losing the possibility of being correctly treated. This phenomenon was similarly observed in a number of countries [35, 38, 56,57,58]. Last, the outpatient assistance of stroke survivors was also highly reduced or stopped. Patients, families, and caregivers were left alone with their needs, and support from patients’ association was penalized [59]. To overcome this lack of assistance, some health-care facilities as telemedicine, which allow patient visits avoiding direct contact with operators and waiting rooms, were implemented. However, although telemedicine was successfully applied for follow-up of patients with rare stroke diseases [36, 60,61,62], it might not be the best solution for stroke patients who are old or have cognitive and language disability.

Italian stroke physicians, other than having a reduced ability to admit acute stroke patients due to overflowed emergency routes or to assist stroke survivors, had to deal with the personal risk of exposure to COVID-19 and overwork, due to personal or colleagues potentially redeployment to assist COVID-19 patients. Since the Italian experience, similarly to most of COVID-19 hit countries, confirmed the priceless contribution of health-care workers, their safety, and healthiness as well as contagion protection should be ensured as a priority. Thus, adequate provision not only of PPEs or other practical measures but also delivery of food as well as rest, family and psychological support should be planned in dealing such a challenging conditions. Continuous screening processes, proper adherence to established infection prevention, control measures, and coordinated team responses are also necessary to ensure a safe clinical stroke team [58, 62]. Meanwhile, scientists around the world should invest resources in providing insight into the relationship between stroke and COVID-19. This information is essential to provide understandable and actionable information and to implement awareness campaign educating patients that even in a pandemic stroke remains a disabling or potentially fatal illness.

In conclusion, although the curve of infection is flatting down, great uncertainties remain on the next future of stroke care delivery and on what is the real impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on stroke care.

It can be easily figured out a short or middle term enormous negative direct and indirect reflection of COVID-19 infection on stroke care. For this reason, health authorities should promptly implement robust action plans to deal with this expected health burden, including investments in increasing services, beds, and workforce to ensure a high level of stroke care to all stroke patients. Stroke awareness campaigns encouraging appropriate hospital evaluation both for acute stroke and stroke survivors also in pandemic time should be supported at local and national level both by specific professional societies and policy makers. Stroke survivors missing follow-up evaluation should be contacted by referring hospitals and encouraged to prompt face to face or virtual evaluation to ensure that secondary prevention measures are properly applied. For this purpose, virtual stroke clinics are being implemented to allow stroke care, meanwhile providing social distancing.

To face future pandemic rebounds, emergency services should be empowered to guarantee acute care availability to all stroke patients and minimize treatment delay. Acute stroke care protocols, which include measures of preservation of clean pathways to optimize the safety of the providing team and patients, deriving from consensus among academic and nonacademic stroke neurologists and interventional neuroradiologists, should be developed [63, 64].

The collaboration between politicians and scientific experts and the data sharing with other international groups are also essential in policy making decisions.

References

COVID-19 information and resources for JHU in https://hub.jhu.edu/novel-coronavirus-information. Accessed 27 August 2020

Remuzzi A, Remuzzi G (2020) COVID-19 and Italy: what next? Lancet 395:1225–1228

Rosenbaum L (2020) Facing Covid-19 in Italy—ethics, logistics, and therapeutics on the epidemic’s front line. N Engl J Med 382:1873–1875

Bersano A, Pantoni L (2020) On being a neurologist in Italy at the time of the COVID-19 outbreak. Neurology 94:905–906

Spina S, Marrazzo F, Migliari M, Stucchi R, Sforza A, Fumagalli R (2020) The response of Milan’s Emergency Medical System to the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Lancet 395:e49–e50

Kohli P, Virani SS (2020) Surfing the waves of the COVID-19 pandemic as a cardiovascular clinician. Circulation. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.120.047901

Dafer RM, Osteraas ND, Biller J (2020) Acute stroke care in the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 29:104881

Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, Guan L, Wei Y, Li H, Wu X, Xu J, Tu S, Zhang Y, Chen H, Cao B (2020) Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 395:1054–1062

Aggarwal G, Lippi G, Michael Henry B (2020) Cerebrovascular disease is associated with an increased disease severity in patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): a pooled analysis of published literature. Int J Stroke 15:385–389

Hui DS, Chan PK (2010) Severe acute respiratory syndrome and coronavirus. Infect Di Clin North Am 24:619–638

Yashavantha Rao HC, Jayabaskaran C (2020) The emergence of a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) disease and their neuroinvasive propensity may affect in COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol 92:786–790

Asadi-Pooya AA, Simani L (2020) Central nervous system manifestations of COVID-19: a systematic review. J Neurol Sci 413:116832

Zubair AS, McAlpine LS, Gardin T, Farhadian S, Kuruvilla DE, Spudich S (2020) Neuropathogenesis and neurologic manifestations of the coronaviruses in the age of coronavirus disease 2019: a review. JAMA Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2065

Montalvan V, Lee J, Bueso T, De Toledo J, Rivas K (2020) Neurological manifestations of COVID-19 and other coronavirus infections: a systematic review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 194:105921

Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, Chang J, Hong C, Zhou Y, Wang D, Miao X, Li Y, Hu B (2020) Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol 77:1–9

Zhou Z, Kang H, Li S, Zhao X (2020) Understanding the neurotropic characteristics of SARS-CoV-2: from neurological manifestations of COVID-19 to potential neurotropic mechanisms. J Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-09929-7

Beyrouti R, Adams ME, Benjamin L, Cohen H, Farmer SF, Goh YY, Humphries F, Jäger HR, Losseff NA, Perry RJ, Shah S, Simister RJ, Turner D, Chandratheva A, Werring DJ (2020) Characteristics of ischaemic stroke associated with COVID-19. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2020-323586

Yaghi S, Ishida K, Torres J, Mac Grory B, Raz E, Humbert K, Henninger N, Trivedi T, Lillemoe K, Alam S, Sanger M, Kim S, Scher E, Dehkharghani S, Wachs M, Tanweer O, Volpicelli F, Bosworth B, Lord A, Frontera J (2020) SARS-CoV-2 and stroke in a New York healthcare system. Stroke 51:2002–2011

Tsivgoulis G, Katsanos AH, Ornello R, Sacco S (2020) Ischemic stroke epidemiology during the COVID-19 pandemic: navigating uncharted waters with changing tides. Stroke 51:1924–1926

Helms J, Tacquard C, Severac F, Leonard-Lorant I, Ohana M, Delabranche X, Merdji H, Clere-Jehl R, Schenck M, Fagot Gandet F, Fafi-Kremer S, Castelain V, Schneider F, Grunebaum L, Anglés-Cano E, Sattler L, Mertes PM, Meziani F (2020) High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med 46:1089–1098

Benussi A, Pilotto A, Premi E, Libri I, Giunta M, Agosti C, Alberici A, Baldelli E, Benini M, Bonacina S, Brambilla L, Caratozzolo S, Cortinovis M, Costa A, Piccinelli SC, Cottini E, Cristillo V, Delrio I, Filosto M, Gamba M, Gazzina S, Gilberti N, Gipponi S, Imarisio A, Invernizzi P, Leggio U, Leonardi M, Liberini P, Locatelli M, Masciocchi S, Poli L, Rao R, Risi B, Rozzini L, Scalvini A, Schiano di Cola F, Spezi R, Vergani V, Volonghi I, Zoppi N, Borroni B, Magoni M, Pezzini A, Padovani A (2020) Clinical characteristics and outcomes of inpatients with neurologic disease and COVID-19 in Brescia, Lombardy, Italy. Neurology. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000009848

Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z (2020) Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost 18:844–847

Clerkin KJ, Fried JA, Raikhelkar J, Sayer G, Griffin JM, Masoumi A, Jain SS, Burkhoff D, Kumaraiah D, Rabbani L, Schwartz A, Uriel N (2020) Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 141:1648–1655

Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, Wu X, Zhang L, He T, Wang H, Wan J, Wang X, Lu Z (2020) Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol 27:e201017. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017

Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, Schiergens TS, Herrler G, Wu NH, Nitsche A, Müller MA, Drosten C, Pöhlmann S (2020) SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 181:271–280

Kuster GM, Osswald S (2020) Switching antihypertensive therapy in times of COVID-19: why we should wait for the evidence. Eur Heart J 41:1857

Kuster GM, Pfister O, Burkard T, Zhou Q, Twerenbold R, Haaf P, Widmer AF, Osswald S (2020) SARS-CoV2: should inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system be withdrawn in patients with COVID-19? Eur Heart J 41:1801–1803

Vaduganathan M, Vardeny O, Michel T, McMurray JJV, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD (2020) Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 382:1653–1659

Stefanini GG, Azzolini E, Condorelli G (2020) Critical organizational issues for cardiologists in the covid-19 outbreak: a frontline experience from Milan, Italy. Circulation 141:1597–1599

Grasselli G, Pesenti A, Cecconi M (2020) Critical care utilization for the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: early experience and forecast during an emergency response. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4031

https://www.regione.lombardia.it/wps/wcm/connect/5e0deec4-caca-409c-825b-25f781d8756c/DGR+2906+8+marzo+2020.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CACHEID=ROOTWORKSPACE-5e0deec4-caca-409c-825b-25f781d8756c-n2.vCsc. Accessed 27 August 2020

Meschi T, Rossi S, Volpi A, Ferrari C, Sverzellati N, Brianti E, Fabi M, Nouvenne A, Ticinesi A (2020) Reorganization of a large academic hospital to face COVID-19 outbreak: the model of Parma, Emilia-Romagna region, Italy. Eur J Clin Invest 50:e13250

Baracchini C, Pieroni A, Viaro F, Cianci V, Cattelan AM, Tiberio I, Munari M, Causin F (2020) Acute stroke management pathway during Coronavirus-19 pandemic. Neurol Sci 41:1003–1005

Caso V, Federico A (2020) No lockdown for neurological diseases during COVID19 pandemic infection. Neurol Sci 41:999–1001

Morelli N, Rota E, Terracciano C, Immovilli P, Spallazzi M, Colombi D, Zaino D, Taga A, Michieletti E, Guidetti D (2020) The baffling case of ischemic stroke disappearance from the Casualty Department in the COVID-19 Era. Eur Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1159/000509002

Markus HS, Brainin M (2020) EXPRESS: COVID-19 and Stroke—a global world stroke organisation perspective. Int J Stroke 15:361–364

WSO; Stroke Care and the COVID19 Pandemic Words from our President. https://www.world-stroke.org/news-and-blog/news/stroke-care-and-the-covid19- pandemic. Accessed 27 August 2020

Montaner J, Barragán-Prieto A, Pérez-Sánchez S, Escudero-Martínez I, Moniche F, Sánchez-Miura JA, Ruiz-Bayo L, González A (2020) Break in the stroke chain of survival due to COVID-19. Stroke. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.120.030106

Avula A, Nalleballe K, Narula N, Sapozhnikov S, Dandu V, Toom S, Glaser A, Elsayegh D (2020) COVID-19 presenting as stroke. Brain Behav Immun. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.077

Gori T, Lelieveld J, Münzel T (2020) Perspective: cardiovascular disease and the Covid-19 pandemic. Basic Res Cardiol 115:32

Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN (2020) The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun 109:102433

Zhao J, Rudd A, Liu R (2020) Challenges and potential solutions of stroke care during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak. Stroke 51:1356–1357

Lancet The (2020) COVID-19: protecting health-care workers. Lancet 395:922

https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331509/WHO-COVID-19-lab_testing-2020.1-eng.pdf. Accessed 27 August 2020

Ahmed F, Ahmed N, Pissarides C, Stiglitz J (2020) Why inequality could spread COVID-19. Lancet Public Health 5:e240

Marshall IJ, Wang Y, Crichton S, McKevitt C, Rudd AG, Wolfe CD (2015) The effects of socioeconomic status on stroke risk and outcomes. Lancet Neurol 14:1206–1218

Ferrario MM, Veronesi G, Kee F, Chambless LE, Kuulasmaa K, Jørgensen T, Amouyel P, Arveiler D, Bobak M, Cesana G, Drygas W, Ferrieres J, Giampaoli S, Iacoviello L, Nikitin Y, Pajak A, Peters A, Salomaa V, Soderberg S, Tamosiunas A, Wilsgaard T, Tunstall-Pedoe H, MORGAM Project (2017) Determinants of social inequalities in stroke incidence across Europe: a collaborative analysis of 126,635 individuals from 48 cohort studies. J Epidemiol Community Health 71:1210–1216

Yancy CW (2020) COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6548

Zaka A, Shamloo SE, Fiorente P, Tafuri A (2020) COVID-19 pandemic as a watershed moment: a call for systematic psychological health care for frontline medical staff. J Health Psychol 25:883–887

Pfefferbaum B, North CS (2020) Mental health and the Covid-19 Pandemic. N Engl J Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp2008017

Choo EK, Rajkumar SV (2020) Medication shortages during the COVID-19 crisis: what we must do. Mayo Clin Proc 95:1112–1115

Hill JA, McGuire DK, de Lemos JA (2020) Science in a time of crisis. Circulation 141:1277–1278

http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_bandi_216_0_file.pdf. Accessed 27 Aug 2020

https://www.ean.org/congress-2020. Accessed 27 Aug 2020

Agarwal S, Sabadia S, Abou-Fayssal N, Kurzweil A, Balcer LJ, Galetta SL (2020) Training in neurology: flexibility and adaptability of a neurology training program at the epicenter of COVID-19. Neurology 94:e2608–e2614

Aguiar de Sousa D, Sandset EC, Elkind MSV (2020) The curious case of the missing strokes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stroke. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.120.030792

Schirmer CM, Ringer AJ, Arthur AS, Binning MJ, Fox WC, James RF, Levitt MR, Tawk RG, Veznedaroglu E, Walker M, Spiotta AM, Endovascular Research Group (ENRG) (2020) Delayed presentation of acute ischemic strokes during the COVID-19 crisis. J Neurointerv Surg 12:639–642

Bersano A, Kraemer M, Touzé E, Weber R, Alamowitch S, Sibon I, Pantoni L (2020) Stroke care during the Covid-19 pandemic: experience from three large European countries. Eur J Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14375

Boldrini P, Garcea M, Brichetto G, Reale N, Tonolo S, Falabella V, Fedeli F, Cnops AA, Kiekens C (2020) Living with a disability during the pandemic. “Instant paper from the field” on rehabilitation answers to the COVID-19 emergency. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. https://doi.org/10.23736/s1973-9087.20.06373-x

Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Shaw S, Morrison C (2020) Video consultations for covid-19. BMJ 368:998. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m998

Hollander JE, Carr BG (2020) Virtually perfect? telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med 382:1679–1680

Khosravani H, Rajendram P, Notario L, Chapman M, Menon BK (2020) protected code stroke. hyperacute stroke management during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Stroke 51:1891

Leira EC, Russman AN, Biller J, Brown DL, Bushnell CD, Caso V, Chamorro A, Creutzfeldt CJ, Cruz-Flores S, Elkind MSV, Fayad P, Froehler MT, Goldstein LB, Gonzales NR, Kaskie B, Khatri P, Livesay S, Liebeskind DS, Majersik JJ, Moheet AM, Romano JG, Sanossian N, Sansing LH, Silver B, Simpkins AN, Smith W, Tirschwell DL, Wang DZ, Yavagal DR, Worrall BB (2020) Preserving stroke care during the COVID-19 pandemic: potential issues and solutions. Neurology 95(3):124–133

Liu R, Zhao J, Fisher M (2020) The global impact of COVID-19 on acute stroke care. CNS Neurosci Ther. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.13442

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Nothing to disclose.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bersano, A., Pantoni, L. Stroke care in Italy at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic: a lesson to learn. J Neurol 268, 2307–2313 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-10200-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-10200-2