Abstract

The significant economic and health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have forced archaeologists to consider the concept of resilience in the present day, as it relates to their profession, students, research projects, cultural heritage, and the livelihoods and well-being of the communities with a stake in the sites they study. The global crisis presents an opportunity to cement archaeological practice in a foundation of community building. We can learn from the ancestors, razana, how investing in community—social networks at different scales—makes us more resilient to crises. In so doing, we can improve the quality and equity of the science we produce and ensure relevant outcomes for living communities and future generations.

Résumé

Les impacts économiques et de santé considérables de la pandémie COVID-19 obligent les archéologues à considérer le concept de résilience à l'heure actuelle, en ce qui concerne leur profession, leurs étudiants, leurs projets de recherche, le patrimoine culturel et les modes de vie et le bien-être des communautés ayant un intérêt dans les sites qu'ils étudient. La crise mondiale offre une opportunité de cimenter la pratique archéologique dans un fondement communautaire. Nous pouvons apprendre de nos ancêtres, les razana, que le fait d'investir dans des réseaux communautaires et sociaux à différentes échelles nous rend plus résistants aux crises. Ce faisant, nous pouvons améliorer la qualité et l'équité de la science que nous produisons et garantir des résultats pertinents pour les communautés vivantes et les générations futures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Times of crisis bring into sharp and, at times, painful focus the degree to which the systems on which we depend are resilient. Archaeologists, with their sweeping view of deeper time, engage with theories of resilience when investigating past lives and experience, claiming to understand the processes that have propelled cultural innovations or precipitated the collapse of social formations. One of the promises of modern archaeology is its potential to reveal insights about the past and to communicate these insights in ways that allow modern society to benefit from historical human experience. Ironically, however, archaeologists themselves do not always practice what they preach. The COVID-19 pandemic has abruptly turned the nail on its head. It is forcing archaeologists to urgently consider the concept of resilience in the present day, as it relates to their profession, students, research projects, cultural heritage, and the livelihoods and well-being of the communities with a stake in the sites they study. Drawing on work in southwest Madagascar, I argue in this essay that the global crisis presents an opportunity to cement archaeological practice in a foundation of community building. As archaeologists, we can learn from the ancestors, razana (Malagasy), how investing in community—social networks at different scales—makes us more resilient to crises. In so doing, we can improve the quality and equity of the science we produce and ensure relevant outcomes for living communities and future generations.

Theories of resilience and community responses to stress are usually expounded and investigated in archaeology (e.g., Faulseit 2015; McAnany and Yoffee 2009; Redman 2005), including in Africanist scholarship to push back against colonial narratives of African insecurity (e.g., Lane 2011; Logan 2020). However, the COVID-19 pandemic and public reckoning with deeply entrenched systemic racism and injustice are exposing weaknesses and persistent inequities in archaeological practice. The massive disruptions imposed by the pandemic have halted the fieldwork economy; made in-person conferences impossible; engendered cuts to research, recruitment, and training budgets; reduced job security; impacted livelihoods of communities around the world; and made tangible and intangible forms of cultural heritage more vulnerable (Ogundiran 2020). Unlike many other more localized public health, economic, and political crises, COVID-19 has impacted Africanist archaeologists inside and outside the continent. As a result, Africanists worldwide have asked what can be done to support African communities with or near whom they work, how delays in collecting archaeological data will impact their careers and those of their students, and how to protect the cultural heritage that may be vulnerable to budget cuts and other financial constraints.

These questions acknowledge that our archaeological practice is highly vulnerable to disruptions. They also suggest that our practice retains the asymmetrical power dynamics of a patron-client system in which principal investigators dictate how, when, and where archaeological work will be done, whether or not communities will be involved, and, if so, what benefits communities will receive for their assistance in obtaining archaeological data (Chirikure 2015). Since the foreign principal investigators have been impacted, the whole system of the foreign archaeological economy appears to stall.

The disproportionate impacts of COVID-19 on people of color and other minoritized communities and the recently publicized murders of black people in the USA have drawn international attention to the persistent ravages of systemic racism. In academic communities, this public reckoning with racism has led to calls for critical self-reflection about the colonialist roots of many fields of inquiry and greater equity and inclusivity in academia. As a result, the movement to decolonize knowledge and practice in the academy has been invigorated. For archaeologists, the time is ripe to evaluate how a patron-client system weakens our ability to engage in rigorous archaeological science, which, I argue, must be equitable and inclusive. Here, I provide a perspective from southwest Madagascar, where we have continued to engage in active research in collaboration with community partners throughout the pandemic shutdown. This perspective speaks primarily to the impacts of the pandemic crisis on the fieldwork economy, budget cuts for field research, and community livelihoods. It highlights elements of archaeological practice that have allowed our project to thrive in the face of the current crises.

The Morombe Archaeological Project (MAP) began in 2011 in the Vezo territories of coastal southwest Madagascar. As we described recently (Douglass et al. 2019), our team aspires to work in a fully collaborative framework in which power is shared among team members and communities at different scales are included in all phases of work, from planning to output. We reported in 2019 that our ability to achieve full collaboration is challenged when our team cannot meet in person (e.g., when the US-based members of the team are not in Madagascar and vice versa; see Douglass et al. 2019, p. 21). However, our project’s strong community foundation and its principle of amy ty lilin-draza’ay (in the ways of our ancestors) have allowed us to meet the challenges of the current pandemic travel and budget restrictions through field research (ongoing since May 2020), reallocation of budgets, and mutual support. COVID-19 is the harbinger of future large-scale disruptions, as we face intensifying climate change, other pandemic outbreaks, rising socioeconomic inequality, and other threats. With this future in sight, three major and interlinked principles of our project—intergenerational knowledge, social networks, and power-sharing—have enabled us to develop effective strategies for coping with the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Intergenerational Knowledge

Beginning in 2017, the MAP reoriented its methodology to make intergenerational knowledge transmission a central component of the project. This reorientation anchored project planning, execution, and output in recording oral histories of olo be (elders), ceremonies to honor and consult ty raza’ay (our ancestors), and other forms of knowledge exchange, including the collaborative creation of the MAP marine fauna comparative collection (Douglass et al. 2019, p. 14–16). One of our most important efforts to foster intergenerational knowledge and build capacity is the Vezo Ecological Knowledge Exchange Project (VEKE). The VEKE was launched in 2019 when the US-based MAP team hosted a diverse delegation of eight Vezo collaborators for a two-week exchange at the Penn State University and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. The delegation of Vezo knowledge holders included elders, a university professor, established community leaders, as well as students and young delegates considered to be future Vezo leaders. The objective was to visit scientific laboratories and collections at both institutions, brainstorm socio-ecological questions of interest to the group that could be answered using a wide array of techniques, and record Vezo knowledge about the Smithsonian’s Malagasy collections (e.g., Vezo classification of plant and animal specimens, the role of certain organisms in Vezo society, oral histories, etc.). The result of the exchange has been an ongoing dialogue about research questions that are of interest to the community, the potential benefits of archaeological and other kinds of socio-ecological research to the community, and funding proposals to support these collaboratively generated ideas. This dynamic dialogue has been ongoing during the pandemic shutdown, and our ability to engage fruitfully in this remote long-distance collaborative environment is possible because of the bonds of equal exchange established during the delegation’s visit to the USA in 2019.

The intergenerational knowledge exchange also opened up the opportunity to include additional questions in our oral history interviews about past epidemic outbreaks and to preserve and disseminate knowledge about such outbreaks and the wide range of responses. The systematic inclusion of raza and olo be in our work through regular consultations, honoring ceremonies, and what we describe as “empowered collaboration” (Douglass et al. 2019, p. 12), has connected our project to community efforts to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. These community efforts include ceremonies conducted in particular locales to ward off the disease (Fig. 1). This engagement has given our archaeological team a new awareness of and appreciation for the meaning and sacred features of Vezo landscapes. Our engagement in intergenerational knowledge exchange has also provided guidance and support for safely conducting fieldwork and contributing in a meaningful way to the local economy.

Social Networks

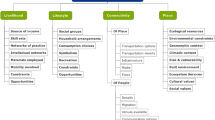

In our ongoing MAP research, we hypothesize that social networks played an important role for ty raza’ay in mitigating the impacts of disturbances (e.g., climate variability, political unrest, and epidemic outbreaks) of differing intensities and frequencies. As a team, we nurture our social network of collaborators and stakeholders at local, regional, national, and international scales (e.g., local women’s association, regional officers of the Ministry of Culture, and Malagasy expatriates, among others). Thanks to the proliferation in Madagascar of inexpensive Internet access, social media platforms such as Facebook enable members of our team all over the world to connect frequently and develop direct ties of friendship and support. As a result, many channels of communication exist across the team, so that ideas and support are not channeled exclusively through the project PI. Multiple channels of communication between diverse team members (youth and elders, men and women, Malagasy and American, etc.) facilitate creative thinking for research, as well as about how we can support our many communities and, in so doing, contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage. A recent outcome of creative thinking across the team was the use of project funds (initially allocated as participant gifts) for the production of 1200 COVID-19 face masks by the Andavadoaka Women’s Association. Our survey team has distributed these masks to communities in the region.

A dense network with a high degree of reciprocity also allows members of our team to express support in meaningful ways when difficult times arise. In the wake of the murder of George Floyd, several of our Malagasy team members reached out directly to the members of the US-based team to offer support and solidarity. An example of this support was participation by a Malagasy member of the MAP team in a virtual Capoeira event. Capoeira, an Afro-Brazilian martial arts tradition, was developed to combat injustice and promote freedom during and after the transatlantic slave trade (Capoeira 2002). This particular event aimed to spotlight the achievements of a black woman (and member of the MAP team), especially her contributions in sharing Capoeira in Madagascar and the positive impact she has had on Malagasy archaeology. The event drew praise and public recognition for her work as a Capoeirista and scholar. Exchanges like this are important for many reasons, not least of which is that they indicate that all members of the team have the power to offer one another support, regardless of where they are based. It is often assumed in postcolonial African contexts that non-Africans are the only ones with the capacity to provide aid. This assumption is both erroneous and damaging to efforts to engage in equitable work.

Power-Sharing

As previously discussed (Douglass et al. 2019), power-sharing is a fundamental principle of how the MAP team operates. African archaeology has a tradition of highlighting examples of alternative forms of social complexity, in which societies are organized heterarchically (McIntosh 2005). These examples are presented as a deviation from assumptions about what sociopolitical complexity entails. These examples encourage self-reflection and the examination of how power is distributed in archaeological practice. In the MAP context, power-sharing manifests in project infrastructure and management. All equipment, including a drone, excavation gear, computers and tablets, and GPS units, are all stored in our field lab and managed by the Madagascar-based team. Everyone is trained to use and maintain the equipment and can make use of the equipment as needed. Decision-making is also decentralized and distributed across the team. This means that during the pandemic shutdown, Madagascar-based team members were able to make a decision, based on local conditions (e.g., local spread of the virus), about whether and where to conduct data collection and analysis. Because the Velondriake region in which the MAP operates has remained relatively isolated from the spread of COVID-19, the survey team opted to carry out fieldwork.

Conclusion

Many have written about the opportunity that COVID-19 presents to look to the past to see how ancient people survived pandemics (Chirikure 2020; Witcher 2020; also see Holl, Pfeiffer, and Ogundiran, this forum) or about the relevance of archaeology in providing a deeper time perspective on how COVID-19 is increasing social inequality today (Dávalos et al. 2020). I argue here, however, that the current crisis also provides the opportunity to reorient archaeological practice, so that we engage in research that not only re-examines theories of community resilience and management of epidemic outbreaks but also models itself on the lessons that our research reveals. This crisis challenges us to critically take stock of the power structure that frames archaeological practice, the ability of this practice to withstand the stress of COVID-19, and the impacts of the pandemic on the lives of archaeologists, students, and communities. Perhaps we can look to the past to investigate how resilient social systems of ty raza’ay might be useful models for archaeological practice today and in the future.

References

Capoeira, N. (2002). Capoeira: Roots of the dance-fight-game. Berkeley: Blue Snake Books.

Chirikure, S. (2015). “Do as I say and not as I do”: On the gap between good ethics and reality in African archaeology. In A. Haber & N. Shepherd (Eds.), After Ethics (pp. 27–37). New York: Springer.

Chirikure, S. (2020). Archaeology shows how ancient African societies managed pandemics. The Conversation https://theconversation.com/archaeology-shows-how-ancient-african-societies-managed-pandemics-138217. Accessed 27 July 2020.

Dávalos, L. M., Austin, R. M., Balisi, M. A., Begay, R. L., Hofman, C. A., Kemp, M. E., Lund, J. R., Monroe, C., Mychajliw, A. M., Nelson, E. A., Nieves-Colón, M. A., Redondo, S. A., Sabin, S., Tsosie, K. S., & Yracheta, J. M. (2020). Pandemics’ historical role in creating inequality. Science, 368(6497), 1322–1323.

Douglass, K., Morales, E. Q., Manahira, G., Fenomanana, F., Samba, R., Lahiniriko, F., Chrisostome, Z. M., Vavisoa, V., Soafiavy, P., Justome, R., Leonce, H., Hubertine, L., Pierre, B. V., Tahirisoa, C., Colomb, C. S., Lovanirina, F. S., Andriankaja, V., & Robison, R. (2019). Toward a just and inclusive environmental archaeology of southwest Madagascar. Journal of Social Archaeology, 19(3), 307–332.

Faulseit, R. K. (Ed.). (2015). Beyond collapse: Archaeological perspectives on resilience, revitalization, and transformation in complex societies. Center for Archaeological Investigations, Occasional Paper 42. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Lane, P. J. (2011). Possibilities for a postcolonial archaeology in Sub-Saharan Africa: Indigenous and usable pasts. World Archaeology, 43(1), 7–25.

Logan, A. (2020). The scarcity slot: Excavating histories of food security in Ghana. Oakland (CA): University of California Press.

McAnany, P. A., & Yoffee, N. (2009). Questioning collapse: Human resilience, ecological vulnerability, and the aftermath of empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McIntosh, R. J. (2005). Ancient Middle Niger: Urbanism and the self-organizing landscape. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ogundiran, A. (2020). Editorial: On COVID-19 and matters arising. African Archaeological Review, 37(2), 179–183.

Redman, C. L. (2005). Resilience theory in archaeology. American Anthropologist, 107(1), 70–77.

Witcher, R. (2020). Editorial: Looking forward, looking back. Antiquity, 94(375), 571–579.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Douglass, K. Amy ty lilin-draza’ay: Building Archaeological Practice on Principles of Community. Afr Archaeol Rev 37, 481–485 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10437-020-09404-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10437-020-09404-8