Abstract

We leverage the largest polio outbreak in US history, the 1916 polio epidemic, to study how epidemic-related school interruptions affect educational attainment. Using polio morbidity as a proxy for epidemic exposure, we find that children aged 10 and under, and school-aged children of legal working age with greater exposure to the epidemic experienced reduced educational attainment compared to their slightly older peers. These reductions in observed educational attainment persist even after accounting for the influenza epidemic of 1918.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The global COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 led to severe disruptions in nearly all aspects of life. Stay-at-home orders closed schools and non-essential businesses, generating widespread unemployment and large declines in economic activity that cannot yet be fully assessed. The social and economic costs of this crisis have been widely felt. A United Nations report suggests that global GDP could decline by 1% (United Nations 2020), while the managing director of the International Monetary Fund stated that she anticipates that the pandemic will generate “...the worst economic fallout since the Great Depression,” with global GDP contracting by 3% (Gopinath 2020). According to UNESCO, over 1.5 billion students, almost 90% of all learners, have had their schooling disrupted by this crisis. At least 189 countries have closed schools in response to the COVID-19 threat, which may interrupt human capital accumulation in children and contributes to the social costs of the pandemic (UNESCO 2020).Footnote 1

While most people alive today have never witnessed this scale of the pandemic, research on other epidemics may provide insights into the possible magnitude of the disruption.Footnote 2 In this paper, we examine the 1916 polio epidemic to measure how it impacted the educational attainment of children during the outbreak. The 1916 epidemic is unique in that it was the first and largest major polio epidemic in the USA and was one of the first major public health crises many nascent public health departments faced.Footnote 3 The 1916 epidemic proved to be the first of many outbreaks that would continue until the advent of the Salk vaccine in 1954, although Trevelyan et al. (2005) suggest that the 1916 epidemic was more intense than subsequent outbreaks.Footnote 4 While smaller in magnitude than the more famous 1918–1919 Spanish flu, the polio epidemic started in New York City and New Jersey, but then spread across the USA, resulting in mass quarantines and prolonged school closures at the start of the 1916–1917 academic school year.

The polio epidemic may have affected educational attainment in two ways. First, infected children may have missed school during the period of their illness and recovery. Second, even children who did not have symptoms missed school during periods of closure or because their parents refused to send them to school. Thus, we leverage geographic variation in the severity of the epidemic, as well as the fact that polio differentially affected children of different ages, to measure how the disease affected the educational attainment reported by these children as adults in the 1940 census. Children living in areas with high polio morbidity were more likely to be infected and more likely to endure school closures than children in less-affected areas. Children under 10 were more susceptible to polio, yet children aged 14 and older may have been more likely to quit school during a prolonged closure and join the labor force.

Our results show that children born in states with more reported polio cases had lower educational attainment compared to slightly older birth cohorts who would have already completed schooling before the 1916–1917 school year and that the decline in educational attainment varied depending on their age during the outbreak. We find that a one-standard-deviation increase in polio intensity reduced years of completed schooling by 0.07 years for children between the ages of 14 and 17 in 1916. For children who were 10 and under during the epidemic (and who were most susceptible to polio), a one-standard-deviation increase led to a 0.1 year reduction in years of completed education. These results are robust to controlling for 1918–1919 influenza intensity.

2 The pathology of polio and the 1916 epidemic

Polio is caused by the poliovirus, an enterovirus transmitted fecal-orally. Evidence on Egyptian stele (depicting an adult with a withered leg and crutch) dating from 1580–1350 BC suggests that polio has existed for thousands of years (Nathanson and Kew 2010). Although the existence of polio dates to antiquity, it was not until the late 19th century that epidemics began occurring in the USA and Europe. The most plausible explanation for this pattern is that before the late 19th and early twentieth centuries, most people were probably exposed to polio during infancy when infants had circulating maternal antibodies that made the infection much less severe. Over the next 100 years, improved public sanitation delayed exposure to the virus, thus increasing both the age of primary infection and the severity of the illness, since maternal antibodies were no longer circulating. As a result, epidemics that became increasingly severe were reported each summer and fall, and the average age of persons infected increased (Nathanson and Kew 2010; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2015).Footnote 5

In 1916, there were over 5000 deaths and 23,000 more documented infections, numbers that eclipsed those of previous (and subsequent) epidemics (Lavinder et al. 1918; Trevelyan et al. 2005). Table 1 details the number of reported polio cases and deaths by state during the epidemic. Nearly every state reported polio cases, with Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut reporting the highest numbers of reported polio infections. While much of the epidemic was in the northeastern USA, there were also sizable outbreaks in Minnesota, Montana and Mississippi.

It is important to note that while cities may be more heavily impacted by modern epidemics, polio was unusual in that it was precisely better hygiene that predisposed victims to a later, and more severe, onset. In places with poor sanitation, children would have been exposed at much younger ages (often infancy, without obvious symptoms) and be less likely to suffer a severe case. While many cities had improved sewer and sanitation (thus leading to the large flare of the epidemic in 1916), rural areas had traditionally been “healthier” places to live from a sanitation standpoint. Lavinder et al. (1918) note that the epidemic was more prevalent and intense in small towns and the country than in large cities, and “...not due to mere chance but to some fundamental law” (p. 19).

The outbreak generated substantial fear. Commonly known as “infantile paralysis,” polio often caused mild (or no) symptoms but could attack the nervous system and cause permanent paralysis. Little was known about how the disease was spread, and no vaccine for polio would be available for another forty years. The disease transcended class lines and affected the poor and the rich alike. In New York City, for example, a large share of cases occurred among native-born children living in single-family dwellings with clean surroundings and indoor toilets (Lavinder et al. 1918).Footnote 6

3 Actions taken to curb the spread of polio

Public health officials struggled to contain the outbreak, which began in June and lasted until November. As the disease spread, officials became increasingly desperate. To prevent the spread of the epidemic and allay public fear, officials implemented various non-pharmaceutical interventions, such as strict quarantines. Placards were also placed in front of homes of infected individuals to notify the community of the public health risk. In at least one case, a child suffering from polio was forcibly removed from his home to a hospital, against the wishes of his parents (Emerson 1917). In New York City, children ages 16 and under were prohibited from leaving New York City for travel unless they produced “... a certificate that the premises occupied by them were free from poliomyelitis, and had been free from this disease since January 1, 1916.” This was supplemented by a medical examination of such travelers at the point of departure (Emerson 1917).

In New York City and Philadelphia, health officials ordered the city streets to be washed with millions of gallons of water each day (Offit 2005; Rogers 1992).Footnote 7 Government policy also called for a ban on public gatherings in areas where numerous cases were reported (Emerson 1917). In the summer of 1916, New York public health officials barred children from movie theaters and libraries, closed Sunday schools and banned picnics (The New York Times 1916c, e; Rogers 1992). Fears that domesticated animals could spread the disease led to the extermination of 72,000 cats and 8000 dogs (The New York Times 1916b). Even though drastic measures were undertaken to control the spread of the disease, hundreds of new infections were reported every week.

As autumn approached, fears that afflicted youths would infect their peers and a belief that quarantines could limit the virus’ spread led many school districts to delay the start of the 1916 school year until the epidemic waned. As the New York Department of Health noted, “The unprecedented virulence and extent of the existing epidemic, and unfamiliarity with the disease, has engendered in the public such a state of mind that concession to public alarm seemed advisable” (Emerson 1917). The extent and nature of these closures varied across political and geographic divisions of the USA due to the decentralized structure of the nation’s public health system.Footnote 8 For example, Pennsylvania and Vermont postponed the start of the school year across the entire state, while states such as Connecticut and New Jersey left the decision up to local public health authorities or local school boards.

New York City schools opened on September 25, two weeks later than the expected September 11th open date (The New York Times 1916d). Newspaper accounts show numerous other cities nationwide joined New York in postponing the start of school. Philadelphia delayed opening schools until September 18th (and then to October 2nd), and both Washington, D.C., and Fort Wayne schools were not reopened until October 2nd (The Washington Times Company 1916; Evening Public Ledger 1916a, b).

Schools closed across the nation even in states with small numbers of cases. For example, some schools closed in Seattle, with only five cases reported (The Tacoma Times 1916). But, even when schools may not have been officially closed, there is evidence that parents worried about sending their children to school.Footnote 9 For example, even after the delayed reopening in New York City, worried parents withheld their children from school; up to 200,000 students were absent the first few weeks after schools opened, and the district announced “leniency” for parents who failed to send their children to school (The New York Times 1916a).

To gain insight into the extent of school closures nationally and when they occurred, we searched newspaper records contained in the Chronicling America Newspaper Archive (Library of Congress 2020). Cities in the most heavily affected areas are most frequently mentioned, but newspaper accounts demonstrate that school closures tended to occur wherever an area experienced a breakout of polio. The epidemic started in June, accelerated in July and persisted through the start of the academic school year. These data most likely represent a subset of school closures, since not all newspapers are covered in the Library of Congress archive. Moreover, our search procedure may have failed to reveal all closures.Footnote 10 Many newspapers referred to school closures in different cities, or even in major cities in other states. Although we found some articles in which a city expressly stated schools would remain open (including Chicago, Detroit and Milwaukee), for most cities we could not ascertain with certainty that they did not close.

In Fig. 1, we plot the frequency of school delay announcements in the Chronicling America Newspaper Archive for all newspapers from July 1, 1916, to November 1, 1916. School postponement notifications in US newspapers began to increase in the weeks preceding the start of the academic school year (normally around September 5 or September 11), peaked during the two first weeks of September and gradually decreased until the first week of October. The latest public school start date we observe in the Chronicling America Newspaper Archive (Library of Congress 2020) was October 2, 1916, although some New England preparatory schools advertised that they postponed their start dates into the middle of October. The newspaper articles also reveal that the persistence of the epidemic caused public health officials and school boards to repeatedly push back school start dates. Washington, DC initially planned to start on time, then pushed back the start two weeks to September 25, and then finally postponed until October 2. Boston, MA did the same. The entire state of Pennsylvania also postponed school starts multiple times until the first week of October.

To dig deeper into the relationship between city-level school closures and polio outbreaks, we further searched for announcements of school closures in 161 cities for which we have polio morbidity data digitized by Van Panhuis et al. (2018). These were cities that voluntarily participated in the disease reporting system conducted by the US Public Health Service, which published this information in its weekly bulletins. We were able to find newspaper accounts of school postponement for 38 of these cities.Footnote 11 Table 10 in the appendix provides more detailed information on the city names, the dates of postponement, and the name of the newspaper in which we found the information. Of these 38 cities, 84% opened over 2 weeks late, with 60.5% opening on October 2, 1916. Only three (Chicago, Detroit, and Milwaukee) opened on time.

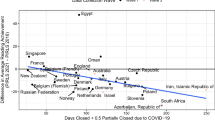

Figure 2 presents the relationship between weekly polio morbidity in these 38 cities and the timing of school postponements using data from Project Tycho.Footnote 12 We highlight the relationship between the epidemic timing and school postponement by separating this information by the timing of the school starts: schools that started on time, schools that delayed their start dates to a later date in September, and schools that delayed school starts into October. A mass of polio outbreaks in August and September coincided with delayed school starts in many affected cities. Polio outbreaks continued in these cities throughout October, and the epidemic ended in November.

In Fig. 3, we focus in on a subset of the reported data for cases under 100 per week. For many cities with schools that opened in October there large numbers of reported weekly polio cases throughout September and well into October. Schools that postponed only a few weeks into September generally had fewer reported cases of acute polio than either the schools that started in October. In the few schools that we confirmed opened on time, most city week observations report low numbers of polio infections. The exception to this pattern is the city of Chicago, which opened schools on time even while polio still spread throughout the community.

4 Polio and educational attainment

There is a broad and well-documented literature in economics and in economic history about the impact of early childhood health and economic shocks on later life outcomes (Almond et al. 2018). Within this literature, there are a number of papers that demonstrate the long-run consequences of infectious disease shocks in childhood. Beach et al. (2016) show that reduced early-life exposure to typhoid improved later life educational attainment, perhaps by improving cognitive functioning.Footnote 13 Bhalotra and Venkataramani (2013) also find that reduced infant exposure to waterborne disease is associated with improved test scores for girls and improved heights for boys. There is also evidence that individuals who do not contract infectious diseases during epidemics can also be affected. For example, Parman (2015) examines the impact of the 1918 influenza pandemic on the siblings of those children born during the outbreak and finds that older siblings received an additional three months of education, while younger siblings received slightly less education relative to children who did not have a sibling born during the pandemic. To our knowledge, no one has examined the case of polio in the USA, which is unique in that educational attainment may have been affected even despite the fact that relatively small numbers of people contracted polio.

The polio epidemic may have reduced educational attainment through two channels. Children who contracted the disease may have missed school while ill, thus reducing educational attainment, although this might depend on whether they contracted a mild form of the disease or paralytic polio. Gensowski et al. (2019) find that children who contracted paralytic polio in Denmark in 1952 were more likely to earn a university degree than children who did not, suggesting that these children shifted investment into education as their comparative advantage moved from jobs requiring certain physical abilities to those requiring more cognitive skills.

Other children may have experienced reduced educational attainment if they missed school for short periods of time due to school closures or avoidance, or if they delayed entry into formal schooling (for example if the parents of a would-be kindergartner decided to wait until the fall of 1917 to send the child to school). Younger children who have their schooling disrupted even for short periods of time may suffer negative effects. For example, Marcotte and Hemelt (2008) find that unscheduled school closings due to weather negatively affect student performance on third-grade state assessment examinations. Middle-grade students may have lower educational attainment if their learning is disrupted during key periods of development (Lloyd 1978; Hernandez 2011). Whether these effects persist in the long run is less clear. Card and Krueger (1992) find that men educated in states with higher-quality schools (measured by term length, student-teacher ratio and teacher wage) have higher returns from their schooling. Pischke (2007) uses data from a German school district that had a one-time shortening of the school year and finds that the short school year had no negative effect on earnings and employment later in life, although it did lead to more students repeating a grade and fewer students entering higher secondary school tracks.

Other research does suggest that interruptions in schooling at crucial points of development may have long-run impacts. Hernandez (2011) suggests that children in third-grade experience a pedagogical shift from “learning to read” toward “reading to learn.” A failure to develop this proficiency in reading on time appears to inhibit human capital accumulation of students and limits the potential to keep pace with their peers. Lloyd (1978) suggests that students who perform at a lower level than their peers may be more likely to drop out of school, with third-grade academic performance accurately predicting whether an individual would drop out of school nearly 70% of the time.Footnote 14

In addition to the effect on younger children of missing school, prolonged school closures may have caused older children of legal working age to exit school and enter the labor force. A sizable literature on the effects of compulsory schooling laws suggests that educational attainment is affected by increases in the legal age of school exit, increases in the age at which children can legally work and decreases in the maximum age of school entrance.Footnote 15 In 1910, 22 states had legislated 14 as the minimum age for employment in manufacturing (Moehling 1999).Footnote 16 Around 16.8% of males and 5.8% of females between the ages of 10 and 15 were active participants of the workforce in 1920, suggesting that many school-age individuals in 1916 would have possessed workforce alternatives to education (Carter and Sutch 1996). Together, this evidence implies that a notably large portion of youth ages 14 and older had viable and legal employment alternatives available to them in 1916. Moreover, if worried parents delayed their youngest children’s entry into school for a year, research by Deming and Dynarski (2008) suggests that these “redshirted” children may have less educational attainment than their non-redshirted peers since they reached a legal working age having acquired fewer years of formal schooling.

5 Data and empirical methodology

Using the 1916 polio epidemic as a natural experiment, this paper examines the effect of epidemics on the educational attainment of children. Our primary identification strategy relies on interacting different age cohorts with polio morbidity rates in an individual’s birth state. Data on polio morbidity at the state level come from Lavinder et al. (1918), who provide comprehensive information pertaining to state-level polio morbidity covering most of the continental USA. We use the data from Lavinder et al because the US Public Health Reports do not include areas with only a few cases (US Surgeon General and US Public Health Service 1917).

In all specifications, we interact data on polio morbidity with dummy variables for an individual’s age in 1916, since children of different ages may have been differently affected by polio. Given that nearly 90% of children infected by polio before 1919 were under the age of 10, they may have been more likely to experience the effects of polio directly than children of older ages (Nathanson and Kew 2010). On the other hand, children who were 14 and over may have been more likely to leave school for the workforce than children of younger ages. A priori, we expect children under 10 and children ages 14 or older to have their educational attainment impacted at a greater rate than those between the ages of 11 and 13.

We use polio morbidity as our primary data for two reasons. First, complete data on school closures are not available, and state-level data on attendance is not reported for the 1916–17 school year.Footnote 17 Second, polio morbidity data enable us to capture both the direct and indirect impacts of polio on children. Polio may have directly affected school attendance for the children who contracted the disease. Since do we not have information on whether specific individuals contracted polio, we instead rely on the polio case (notification) rate in an individual’s birth state. In addition, the epidemic may have indirectly affected children who missed school either because schools closed, or because fearful parents kept them at home. Schools in areas with higher rates of polio were more likely to close, and parents were more reluctant to send their children to school even when schools were open. Relying on school closure data may fail to capture some of these “avoidance” behaviors. For example, data on average daily attendance for five boroughs in New York City (available only between 1911 and 1917) indicate that average daily school attendance in New York City fell in the 1916–17 school year, as shown in Fig. 4.

We measure 1916 polio epidemic exposure by reported infections at the state-level so that our main identifying assumption is that people who were school age in 1916 would be exposed in their state of birth. This assumption would be violated if children and adolescents migrated between states prior to the 1916 epidemic. While we can only speculate as to the number of children who moved across states during childhood, we do know that in 1940, 77% of people were residing in the same state in which they were born. Further, migration would bias the treatment effect toward zero if migration prior to the epidemic was not systematically correlated with polio morbidity. Using data from the 1920 US Census, we find that the difference between state of birth and state of residence in 1920 is less of a concern and that assigning polio virulence to state of birth is a reasonable proxy for exposure to the 1916 epidemic. In Fig. 5, we present the share of persons who were not observed in their state of birth in the 1920 Decennial Census. On average, 84% of people ages 0 to 21 in 1916 in states that reported polio still resided in their state of birth.

To test whether the epidemic influenced the educational attainment of exposed cohorts, we match a sample of white males born between 1895 and 1916 with the 1916 polio morbidity rate in their state of birth, and the years of education they report having in the 1940 US Census (Ruggles et al. 2019). We restrict the sample to males since they entered the workforce as permanent participants.Footnote 18 We also exclude blacks, since Margo (1986) finds that the highest grade of school reported in the 1940 Census does not accurately represent years of schooling received for African Americans. Table 2 reports summary statistics for the primary sample.

Equation (1) represents the reduced form empirical regression used to study the effects of the 1916 epidemic on educational attainment:

\(Y_{i,b,s,a}\) denotes years of completed education for individual i, born in state b, residing in state s in 1940, and born in birth year cohort a. To compare the relationship between polio morbidity in 1916 and educational attainment, we compare the educational attainment of persons born between 1899 and 1916 (who were between the ages of 0 and 17 at the time of the epidemic) to those who were born between 1895 and 1898 (who were between the ages of 18 and 21). This allows us to compare the educational attainment of persons who plausibly could have been in school with those who would have already completed school. In order to test our hypothesis that children of different ages may have been deferentially impacted by the polio epidemic based on their labor market alternatives, we bin them into four age groups: ages 14–17 (born 1899–1902), ages 11–13 (born 1903–1905), and children under age 10 (born 1906–1916). We interact 1916 polio morbidity per 1000 population (\(Polio_{b}\)) in an individual’s birth state with these age-specific cohort groups (\(AgeBin_{a,j}\)). The omitted cohort is individuals aged 18 to 21 (born 1895-1898).

The variables \(\varvec{\alpha _{b}}\), \(\varvec{\kappa _{s}}\), and \(\varvec{\gamma _{a}}\) denote state of birth, state of residence in 1940, and age cohort fixed effects. The identification of polio morbidity’s effect on educational attainment comes from comparing different age cohorts from the same birth state while controlling for current state of residence, and national shocks common across birth cohorts. State of birth fixed effects control for factors common across persons born in the same state, and state of residence fixed effects control for factors that are shared among persons residing in the same 1940 enumeration state. Common shocks shared across birth year cohorts, such as WWI, are controlled for using birth year fixed effects. In the full specification, we also include state-level economic and demographic controls for 1916 by state of birth, and control for schooling laws that applied to each birth year cohort from each state.Footnote 19 These controls are denoted by \(\varvec{X_{b}}\) and include doctors per capita in 1916, education expenditures per capita in 1916, the natural log of manufacturing wages per earner in 1916, and the natural log of population in 1916. Interacting these controls with age cohort fixed effects allows the effect of these state-level characteristics on educational attainment to vary across different age cohorts. These interactions allow the state-level treatment effect of the epidemic to vary across birth year cohorts. The schooling laws, constructed by Lleras-Muney (2002), denote the ages of mandatory school entry, age of school exit and age at which children could obtain work permits for each birth year cohort from each state of birth. These laws proxy for idiosyncratic changes in schooling regulations for each state of birth by birth year cohort.Footnote 20 Finally, \(\epsilon _{i,b,s,a}\) denotes a heteroskedastic error term clustered by state of birth.

6 Empirical results

In our analysis, we run three different regressions, reported in Table 3. Columns (1)–(3) report results from estimating equation (1) with the years of schooling as the dependent variable. Column (1) includes fixed effects for state of residence in 1940, state of birth, and birth year. Column (2) also includes the full set of fixed effects and birth state by age-cohort trends to control for potential underlying geographic trends common across cohorts born in different areas of the country, and column (3) replaces the trend variables with flexible state of birth economic and demographic controls for 1916 interacted with age cohort dummies, and adds schooling law controls. All coefficient results discussed refer to our preferred and most restrictive specification, (3), unless otherwise noted.

6.1 Evidence from state-level polio morbidity

Results presented in Table 3 confirm our hypothesis that the polio epidemic of 1916 had different effects on educational attainment for children of different ages. School-aged children who were old enough to have labor market alternatives (i.e., those who were between ages 14 and 17 in 1916) and those who were living in areas more affected by the epidemic had lower educational attainment than similarly-aged children living in areas with lower polio morbidity rates. This result is robust even in our models with the most restrictive controls. A one-standard-deviation increase in the polio morbidity rate per 1000 persons (reported as 0.415 in Table 2) results in persons ages 14–17 having around 0.066 fewer years of educational attainment on average. The reference cohort of persons ages 18–21 had, on average, nine years of education. A back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that this effect is equivalent to every fifteenth individual completing one less year of education. There is also a statistically significant and negative relationship between polio morbidity and educational attainment for children 10 and under. The estimated coefficient suggests that a one-standard-deviation increase in polio morbidity decreases educational attainment by 0.111 years—the equivalent of one in ten people of the cohort completing one less year of education.Footnote 21

In contrast, state-level polio morbidity in 1916 does not have a statistically significant relationship with educational attainment in individuals who were over 10, but too young to legally work in most states. The estimated coefficients on the interaction between polio morbidity and persons ages 11 to 13 in 1916 are negative, although the standard errors are large and they are not precise zeros. Relative to individuals born before 1898, the educational attainment of people born in those years do not appear to be strongly affected by polio morbidity rates.Footnote 22 We test whether our results are robust to using two-year age groupings. Results (reported in the appendix) are robust and confirm our main findings: that students with the ability to work legally, and children younger than 10 experienced reduced educational attainment relative to children in the middle grades.

6.2 Evidence from county level polio morbidity

In addition to state-level data, we have county-level data on polio morbidity from Lavinder et al. (1918) for a select set of states in the eastern USA, as shown in Fig. 6. These county data cover the Northeastern part of the USA, which experienced much higher rates of polio cases and deaths than other regions. While we do not have data on county of birth, we can connect this county-level measure of polio intensity to county of residence in 1940 and restrict the sample to persons residing in the same state they were born in. Essentially, we assume that people living in a particular county in 1940 (as long as it is in their birth state) were also born in this county. If we assume that migration within the USA between 1916 and 1940 is not systematically correlated with polio morbidity in 1916, then migration bias would just introduce classical measurement error in county-level exposure to the 1916 epidemic.Footnote 23

The results using the county-level polio morbidity in Table 4 mirror the results using state-level data. While the estimated coefficients are smaller, the relationship between education and polio is negative and statistically significant for all cohorts ages 0 to 17 in 1916. These results suggest that children living in counties with greater polio cases in 1916, on average, had lower levels of educational attainment than slightly older persons. A one-standard-deviation increase in county-level polio cases reduced the educational attainment of persons born between ages 14 to 17 by 0.07 years relative to the reference cohort born a few years earlier. Similarly, persons aged 11–13 also experienced reduced educational attainment; a one-standard-deviation increase in polio morbidity in this age group reduced educational attainment by 0.08 years. Children under 10 during the polio epidemic had the largest reductions in educational attainment, with a one-standard-deviation increase in polio morbidity associated with a 0.13 year reduction in average educational attainment.

6.3 Robustness

6.3.1 Alternative specification: using age-specific infection rates instead of age bins

We also examine whether our results are robust to two alternative specifications. First, the 1916 polio outbreak primarily affected young children under the age of five. As sanitation improved, epidemics in later decades tended to infect older children more frequently. Using age-specific infection rates for the 1916 polio epidemic from a study by Dauer (1938) in Boston, we substitute our interaction of the polio notification rate variable with age category bins with a new variable created by interacting the polio notification rate for 1916 and the age-specific polio infection rate from Dauer (1938). We assign infection risks of 68% for persons under age four in 1916, 20% for persons ages 5 to 9, 8% for persons ages 10 to 19, and 4% for anyone above the age of 19. In Table 5, we present the main regressions specifications using this alternative measure of polio epidemic exposure. The negative and statistically significant coefficients in specifications (1) and (3) are consistent with our main findings and are larger in magnitude. According to specification (3), for persons aged four and under, an increase in polio cases by one per 1000 people decreased educational attainment by 0.505 years. For persons between ages five and nine, the reduction in educational attainment was 0.06 years, while educational attainment fell by 0.024 years for people aged 10 to 19 during the epidemic.

6.3.2 Controlling for influenza

It is also plausible that persons exposed to the 1916 polio epidemic were also affected by the 1918 influenza pandemic, which killed over 500,000 people in the USA. The flu came in three waves. The first, with low mortality, came in the spring of 1918. A second wave associated with higher mortality came in fall/winter 1918, with a third wave arriving in early 1919. We include the 1918–19 flu mortality rates from Garrett (2008), the United States Bureau of the Census (1921), and the United States Bureau of the Census (1922) into our analysis, since public health departments were not required to report influenza cases. Table 6 provides state-level data on influenza deaths by state in 1918 and 1919.

To control for the intensity of the 1918 influenza epidemic, we include the state-level 1918 influenza mortality rate interacted with age bins in our regression, even though the disease was most virulent and lethal in older populations than the children we focus on (i.e., adults of prime-working age). This exercise addresses potential concerns that the 1916 polio epidemic is spuriously correlated with 1918 influenza intensity.Footnote 24 We study the effects of influenza intensity on observed education in 1940 for a subset of states used in the main analysis (27 of 43).Footnote 25

Results reported in Table 7 show that including the influenza death rate and its interactions with age groups does not affect our finding that children of legal working age in states with greater numbers of polio cases had less educational attainment. It attenuates the statistical significance of the 1916 epidemic for children ages 0 to 10 in 1916 in specifications (1) and (2) but strengthens it in specification (3). The effect of influenza mortality itself on educational attainment is statistically insignificant in specifications (1) and (2). In specification (3), we find influenza mortality increases educational attainment for persons born between 1903 and 1916. This result is consistent with the findings in Parman (2015), who shows that families adjusted educational investments in children in response to reduced human capital caused by prenatal exposure to the 1918 flu: slightly older children with siblings who were prenatally exposed to the flu pandemic experienced increased educational attainment.

6.3.3 Falsification

To further substantiate the main results, we also perform a placebo test comparing men ages 22 to 33 in 1916 to reference cohort of those ages 18 to 21. Results, reported in Table 8, indicate that there is not a consistent pattern between reported polio morbidity and educational attainment. There is a small, negative and statistically significant relationship between polio intensity and the level of education observed for the age 22 to 24 cohort at the 10% level in specification (3). However, this relationship is not consistent across all specifications, suggesting that polio morbidity at the state level is relatively uncorrelated with unobserved factors that could affect observed educational attainment in 1940. In the appendix, we include an additional specification test using two-year birth cohorts, which do not substantively change our results.

6.3.4 Results using female-only sample

Our primary results focus on men because they had more workforce opportunities and may have responded differently to polio than women. Table 9 reports results from our primary specification on a sample of women in 1940. We find that the polio epidemic affected girls under age 10 in a similar way to men. Girls aged 14–17 also reported reduced educational attainment in high-polio areas, although not in our most saturated model. In our male sample, we find that boys aged 11–13 living in areas with higher polio did not have a statistically significant lower educational attainment than boys living in areas less affected by polio, although the standard errors are large and the results are an imprecise zero. For girls aged 11–13, the estimated coefficients are negative and statistically significant. We are not sure why. In general, males and females had different returns to education, and it might have been that girls, for whatever reason, did not return to school in the same numbers as their male counterparts.

7 Conclusions

The first major polio epidemic in the United States struck in the summer of 1916 and persisted into the fall. With over 23,000 cases of polio diagnosed, the epidemic tested the nascent system of public health departments. Officials engaged in a variety of measures to stem the outbreak, including quarantines, washing streets, and closing public schools. In this paper, we focus on the effect of the epidemic on years of schooling reported by individuals in the 1940 US Census. Educational attainment could have been reduced for infected children, or for children who spent less time in school because their schools were closed or because their parents refused to send them. While we do not have data on school closures, we leverage geographical variation in polio morbidity as a proxy and focus on whether children of differential ages were differently affected. Younger children were more likely to have the virus, and older children may have opted to join the workforce instead of stay in school. Our results show that children of legal working age living in areas with higher rates of polio infection had diminished educational attainment than similarly aged children living in states with lower infection rates. This result, which is robust and consistent across specifications, does not hold for age groups who were not of legal working age, nor does it hold for slightly older children who had already completed their secondary schooling. We find stronger negative educational effects for children who were most susceptible to the virus and who were age 10 and under during the epidemic.

Our results suggest that a one-standard-deviation increase in polio intensity during the 1916 epidemic reduced educational attainment by 0.07 years for the age 14–17 cohort and 0.11 years for the cohort age 10 and younger. Based on the average reported days in the school year, these numbers suggest that annual attendance declined by roughly 11 days in the age 14–17 group and 17 days among children aged 10 and under. These numbers are not trivial; they are within the range of Lleras-Muney’s (2002) finding that compulsory attendance and child labor laws increased educational attainment by about 18 days. Another way of looking at the impact is to look at the aggregate effect in the cohort. For the cohort of children aged 14–17 during the epidemic, these numbers suggest that on average, about 1 out of 15 of them had one year less of educational attainment in their lifetime. The impact is even larger among younger children, with one out of every 10 children attaining one less year of education.

These cohort-wide reductions in educational attainment suggest that public quarantines, school closures, and parental fear magnified the social cost of the 1916 poliomyelitis epidemic, and may shed light on how epidemics can affect even people who do not contract the illness. Clearly, school closures, even for short times, may reduce educational attainment among affected children. Today, with virtual instruction, it is likely that these effects may be smaller. It is also likely that the impact on high-school completion will be mitigated because many jobs require high school diplomas. Nevertheless, greater numbers of students are now enrolled in college. These results suggest that if these students leave school (either because they do not like virtual learning, or have a negative financial shock), they may be less likely to return and suffer from lower overall educational attainment as a result.

County polio notifications per 1000 in 1916 for select counties, nine quantile bins. Collected from Lavinder et al. (1918)

Availability of data and material

Replication Files will be available through OpenICPSR or Cliometrica

Notes

During the Ebola outbreak, five million children in Africa faced school closures (Sifferlin 2014). Schools in Sierra Leone were closed for nine months, and schools in Guinea and Liberia were closed for six months (Sifferlin 2014; Paye-Layleh 2015). In Nigeria, schools that were supposed to open in August remained closed until October (BBC News 2014).

Studies examining the impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak on the Chinese economy show that it resulted in temporary negative shocks to tourism, retail sales and personal consumption, as well as a 0.5% reduction in GDP (Siu and Wong 2004; Hanna and Huang 2004). More recent studies of the impact of Ebola on the countries of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone suggest that “aversion behavior”—the actions taken by people to avoid illness, and the actions taken by investors as they anticipate these behaviors—led to a loss of $1.6 billion in 2015, or about 12% of their combined GDP (Thomas et al. 2015).

Prior to 1916, most of the US population had limited experience with the poliovirus. While minor and relatively isolated outbreaks occurred previously in the USA, the 1916 outbreak affected more than three times the number of people relative to previous years. In 1916, 28.5 cases of polio were reported per 100,000 people, compared to the 1909–1915 rate of 7.9 per 100,000 population (Paul 1971; Nathanson and Kew 2010).

The 1916 outbreak had greater rates of morbidity than later epidemics, and there is evidence that the 1916 epidemic may also have been under-reported (Nathanson and Kew 2010).

In most cases, patients infected with polio are asymptomatic or experience minor symptoms that resolve in a week (including fever, sore throat, headache or nausea) (Oshinsky 2005; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2015). In some individuals (about one in 150 persons infected), the virus can enter the bloodstream and then invade the central nervous system, leading to paralysis. The extent and duration of the paralysis differs across individuals, while some people recover completely, others may remain permanently weak or paralyzed (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2015).

While polio outbreaks tended to follow seasonal patterns, the geography of outbreaks was unpredictable. Areas that experienced pervasive and widespread viral outbreaks one year might never again see a significant outbreak.

For a thorough discussion of how US institutions that promoted individual liberty over centralization affected public health, please see Troesken (2015).

Closing schools in response to outbreaks and parental concern about outbreaks continued to occur throughout the 20th century. Clausen and Linn (1956) report that following an outbreak of polio in the Boston area in July 1955, officials delayed opening schools for two weeks. Over 80% of mothers surveyed in three Boston area communities reported avoiding crowds, and up to 60% believed that schools should not have opened on schedule (Clausen and Linn 1956).

The search used the entire Chronicling America Newspaper Archive for the USA during the active epidemic. The search required either the word(s) “polio” or “poliomyelitis” or “infantile” or “paralysis” to be referenced on the same page as the words of “school” and “postpone”. We allowed the words “school” and “postpone” to be within five words of each other. Many articles even referred to the disease as the “baby plague” or “plague”. Searches for “school closures” also yielded similar results, but with a flatter distribution and wider tails because they often referred to Sunday school closures.

To identify these cities, we searched for newspaper articles between July 1 and November 1, 1916 that referenced both the polio epidemic and the words “school postponement.” We used “school postponement” because this phrase frequently identified policy actions taken by public health authorities and school boards to postpone the start of the school year for public schools. Using the search term “school closures” instead tended to identify Sunday school closures in July and August, rather than actions were taken to postpone the opening of public schools. As a final step, we examined articles that mentioned specific city names and the word “school” within five words each.

Data of the week starting August 19, 1916, and ending August 26, 1916, are not reported in the Project Tycho data. We included a subset of cities reporting polio morbidity from tables in weekly Public Health Reports to help address this missing information (Public Health Service 1916).

Case and Paxson (2009) find a strong association between early life typhoid infection and later-life cognitive function.

We cannot say with certainty that these modern findings would hold true for the cohort of school-agers in 1916. While we could not find state-level data on school curricula during this period, Goldin and Katz (1999) note that the modern version of high schools, “...one that we would easily recognize today–emerged c. 1910” (p. 689).

An analysis of these laws by Moehling (1999) shows that state minimum working-age legislation had little effect on youth employment in manufacturing and that much of the decline in the use of child labor cannot be attributed to these legal restrictions. Furthermore, the laws setting age 14 as the minimum age for manufacturing employment were comparable to much of the state legislation during this period. Lleras-Muney (2002) notes that state laws for the minimum age of a work permit and the legal age for starting and leaving school are not harmonized and are, in fact, complex. However, it is true that the legal age for work permits in 37 states at this time was 14. Only in OH, MI, CA and SD were the age restrictions higher at 15.

Prior to 1916, information on enrollment, attendance and length of the school year was reported in the Annual Report of the US Commissioner of Education. However, in 1916, the office switched to reporting biennially, and the information was not reported in 1916/17 (U.S. Bureau of Education 1917). To try to disentangle the school closure effect from other effects, we did run regressions using a sample of 15 of the 38 cities we found specific closure dates for in our search of newspapers that also were big enough to be listed as a place of residence in the 1940 census. While statistically significant in one specification, results (available upon request) show the same general pattern we describe below.

Males in the early 20th century had greater labor market alternatives to schooling relative to women. It is less clear a priori how polio morbidity would affect the labor market decisions of girls, but we also run the model on women only and discuss results in our robustness checks.

We thank Adriana Lleras-Muney for providing these data.

The mandatory schooling law data start in 1915 and continue until 1939. We assign the cohort-specific law by subtracting the year the law was enacted from the age students can leave school. This identifies the birth year cohort to which the law plausibly applied. The laws are assigned for each year of birth by state of birth. In cases where there might be more than one applicable law, we assign the minimum age implied by the laws. In the case of missing values, we linearly interpolate if the missing value is between two birth years. In cases where we cannot linearly interpolate, we assign the schooling law from the closest birth year without a missing value in the state of birth, e.g., if values for birth years 1895 and 1896 are missing and we have values for 1897, the values for 1897 are assigned to the earlier cohorts. This process works for all states except for Wyoming where we cannot assign variable values for 58 individuals. Inclusion or exclusion of the schooling laws has little effect on estimated regression coefficients.

To get this value, divide one by the marginal effect for an average person in the cohort, rounding up.

The results are robust to the merging of the 1898 cohort with the reference cohort.

Measurement error could occur, however, if people move between high-morbidity and low-morbidity areas for reasons related to education–for example, if people born in rural counties moved to more urban counties for jobs. In this case, we may be overstating the impact of polio morbidity on educational attainment at the county level. For this reason, we have more confidence in the state-level results that aggregate rural and urban counties and include state of residence in 1940 fixed effects that further control for migration. An alternative method would be to link individuals observed between the 1920 and 1940 Censuses and assume that if they reside in the same county, they were likely born in that county. This could further reduce measurement error, but requires significant resource investment and is still not entirely free of measurement error.

Furthermore, contrary to this paper’s focus, most research studying the 1918 influenza have focused on testing the Fetal Origins Hypothesis. The human capital effects of the influenza pandemic appear in persons exposed prenatally (Almond 2006).

Data is available only for these states because the US Public Health Department did not require states to report influenza cases.

References

Almond D, Currie J, Duque V (2018) Childhood circumstances and adult outcomes: act II. J Econ Lit 56(4):1360–1446

Almond DV (2006) Is the 1918 influenza pandemic over? Long-term effects of in utero influenza exposure in the post-1940 U.S. population. J Polit Econ 114(4):672–712

Angrist JD, Krueger AB (1992) The effect of age at school entry on educational attainment: an application of instrumental variables with moments from two samples. J Am Stat Assoc 87(418):328–336

BBC News (2014) Ebola outbreak: Nigeria closes all schools until October. BBC News

Beach B, Ferrie J, Saavedra M, Troesken W (2016) Typhoid fever, water quality, and human capital formation. J Econ Hist 76(1):41–75

Bhalotra SR, Venkataramani A (2013) Cognitive development and infectious disease: gender differences in investments and outcomes. IZA discussion paper no. 7833

Card D, Krueger AB (1992) Does school quality matter? Returns to education and the characteristics of public schools in the United States. J Polit Econ 100(1):1–40

Carter SB, Sutch R (1996) Fixing the facts: editing of the 1880 U.S. census of occupations with implications for long-term trends and the sociology of official statistics. Hist Methods 29(1):5–24

Case A, Paxson C (2009) Early life health and cognitive function in old age. Am Econ Rev 99(2):104–09

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015) Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases, 15th ed. Public Health Foundation

Clausen J, Linn E (1956) Public reaction to a severe polio outbreak in three Massachusetts communities. Soc Probl 4(1):40–51

Dauer CC (1938) Studies on the epidemiology of poliomyelitis. Public Health Rep 53(25):1003–1063

Deming D, Dynarski S (2008) Symposia: investment in children: the lengthening of childhood. J Econ Perspect 22(3):71–92

Emerson H (1917) A monograph on the epidemic of poliomyelitis (infantile paralysis) in New York City in 1916: based on the official reports of the Bureaus of the Department of Health. MB Brown Printing & Binding Company, p 6

Evening Public Ledger (1916a) Fort Wayne to defer opening. Evening Public Ledger, p 2

Evening Public Ledger (1916b) School opening postponed. Evening Public Ledger

Garrett TA (2008) Pandemic economics: the 1918 influenza and its modern-day implications. Federal Reserve Bank St. Louis Rev 90

Gensowski M, Nielsen TH, Nielsen NM, Rossin-Slater M, Wüst M (2019) Childhood health shocks, comparative advantage, and long-term outcomes: Evidence from the last danish polio epidemic. J Health Econ 66:27–36

Goldin C, Katz LF (1999) Human capital and social capital: the rise of secondary schooling in America, 1910–1940. J Interdiscip Hist 29(4):683–723

Gopinath G (2020) The great lockdown: worst economic downturn since the great depression. Int Monet Fund Blog 114:4

Hanna D, Huang Y (2004) The impact of SARS on asian economies. Asian Econ Pap 3(1):101–112

Hernandez D (2011) Double jeopardy: how third-grade reading skill and poverty influence high school graduation. Published: The Annie E Casey Foundation

Lavinder CH, Freeman AW, Frost WH (1918) Epidemiologic studies of poliomyelitis in New York City and the Northeastern United States during the year 1916. Public Health Bull 91

Library of Congress (2020) Chronicling America: historic American newspapers. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov. Accessed 4 Apr 2020

Lleras-Muney A (2002) Were compulsory education and child labor laws effective? An analysis from 1915 to 1939 in the U.S. J Law Econ 45(2):401–435

Lloyd DN (1978) Prediction of school failure from third-grade data. Educ Psychol Meas 38:1193–2000

Marcotte DE, Hemelt SW (2008) Unscheduled school closings and student performance. Educ Finance Policy 3(3):316–338

Margo RA (1986) Race, educational attainment, and the 1940 census. J Econ Hist 46(1):189–198

Margo RA, Finegan TA (1996) Compulsory schooling legislation and school attendance in turn-of-the century America: a ‘natural experiment’ approach. Econ Lett 53:103–110

Moehling CM (1999) State child labor laws and the decline of child labor. Exp Econ Hist 36(1):72–106

Nathanson N, Kew OM (2010) From emergence to eradication: the epidemiology of poliomyelitis deconstructed. Am J Epidemiol 172(11):1213–1229

Offit P (2005) The cutter incident: how America’s first polio vaccine led to the growing vaccine crisis. Yale University Press, London

Oshinsky DM (2005) Polio: an American story. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Parman J (2015) Childhood health and sibling outcomes: nurture reinforcing nature during the 1918 influenza pandemic. Exp Econ Hist 58:22–43

Paul JR (1971) A history of poliomyelitis. Yale University Press, London

Paye-Layleh J (2015) Liberia schools reopen after 6-month ebola closure. In: The Boston globe

Pischke JS (2007) The impact of length of the school year on student performance and earnings: evidence from the German short school years. Econ J 117(523):1216–1242

Public Health Service (1916) Weekly reports for September 15, 1916. Public Health Rep 31(37):2485–2538

Rogers N (1992) Dirt and disease: polio before FDR. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick

Ruggles S, Flood S, Goeken R, Grover J, Meyer J, Pacas J, Sobek M (2019) IPUMS USA: Version 9.0. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS. 10.18128 D 10

Sifferlin A (2014) 5 Million kids aren’t in school because of Ebola. In: Time

Siu A, Wong Y (2004) Economic impact of SARS: the case of Hong Kong. Asian Econ Pap 3(1):62–83

The New York Times (1916a) 200,000 Children stay away from school. The New York Times

The New York Times (1916b) 72,000 Cats killed in paralysis fear. The New York Times

The New York Times (1916c) Bar all children from the movies in paralysis war. The New York Times

The New York Times (1916d) New York schools open doors today. The New York Times

The New York Times (1916e) Paralysis kills 22 more babies in New York City. The New York Times

The Tacoma Times (1916) Seattle has five paralysis cases; school is closed. The Tacoma Times 9/25/1916

The Washington Times Company (1916) Schools in N.Y. to be kept closed till epidemic end. The Washington Times, p 3

Thomas MR, Smith G, Ferreria FHG, Evans D, Maliszewska M, Cruz M, Himelein K, Over M (2015) The economic impact of Ebola on sub-saharan Africa: updated estimates for 2015. Technical report. World Bank Group

Trevelyan B, Raynor-Smallman M, Cliff AD (2005) The spatial dynamics of poliomyelitis in the United States: from epidemic emergence to vaccine-induced retreat, 1910–1971. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 95(2):269–293

Troesken W (2015) The pox of liberty. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

UNESCO (2020) Covid-19 educational disruption and response. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse. Accessed 26 Apr 2020

United Nations (2020) Covid-19 likely to shrink global gdp by almost one per cent in 2020. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2020/04/covid-19-likely-to-shrink-global-gdp-by-almost-one-per-cent-in-2020/. Accessed 26 Apr 2020

United States Bureau of the Census (1921) Mortality statistics 1919. Twentieth annual report, vol 20. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC

United States Bureau of the Census (1922) Mortality statistics 1920. Twenty-first annual report, vol 21. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC

U.S. Bureau of Education (1917) Report of the commissioner of education made to the secretary of the interior for the year ended June 30, 1917, vol I. G.P.O, Washington

U.S. Surgeon General, U.S. Public Health Service (1917) Weekly reports for June 27, 1917. Public Health Reports 32(26):1013–1074

Van Panhuis W, Cross A, Burke D (2018) Counts of acute poliomyelitis reported in United States of America: 1912–1971 project Tycho data release, version 2.0, April 1, 2018. https://doi.org/10.25337/T7/ptycho.v2.0/US.398102009.

World Health Organization (1999) WHO global action plan for laboratory containment of wild polioviruses. Technical report. World Health Organization

Acknowledgements

Thomasson acknowledges support from the Julian Lange Professorship. We thank Bill Even, Price Fishback, Carl Kitchens, and Martin Saavedra for valuable comments. All errors remain our responsibility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

None to declare

Conflicts of interest

None to declare

Code availability

Replication Files will be available through OpenICPSR or Cliometrica

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix

Reference cohort sensitivity analysis

We test sensitivity of our main analysis using alternative reference cohorts. The main analysis uses persons who would have been between 18 and 21 during the polio epidemic. We prefer using multiple birth year age bins study the polio epidemic. This is because our age variable is constructed from year of birth, there is some imprecision in lining up school attendance and age in 1916. In particular, some persons who reach the age of 18 in 1916 may have started the school year as 17 year olds. We find a relatively negative and consistent relationship between polio virulence and the age someone was in 1916.

We redo the main regressions using persons aged 19–21, 20–21, 21, 18–20, 18–19, and 18 as reference cohorts. We include an additional interaction between polio and the age cohorts removed from the reference cohort as a “Placebo Cohort.” We find results consistent with our main analysis. Using single year reference or falsification cohort in a specification using multiple year bins can alter the statistical significance of our results. Potential issues arise from using either 18 year olds alone as a reference cohort or using 18 year olds alone as a falsification cohort. Our preferred specifications using 1916 Economic Controls attenuate these effects, the regressions with these controls present negative and statistically significant results consistent with the main regression specification (Tables 13, 14).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Meyers, K., Thomasson, M.A. Can pandemics affect educational attainment? Evidence from the polio epidemic of 1916. Cliometrica 15, 231–265 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-020-00212-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-020-00212-3