Abstract

The aim of the present study is to consider a heroin epidemic model with age-structure only in the active heroin users. The model was formulated with the help of available literature on heroin epidemic. Instead of treatment as a class, we incorporated recovered population and considered treatment as a control variable and thus a control problem is presented for further analysis. The techniques of weak derivatives and sensitivities were used for obtaining the adjoint equations. The maximum principle of Pontryagin’ type was used for obtaining the optimal value of the control variable. Sample simulations are presented at the end of the study in order to show the effectiveness of the treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Heroin is an illegal, highly addictive opioid drug made from morphine. Morphine is an organic compound which is produced from the seed pod of a certain plant, called opium poppy [1, 2]. Such plants are widely grown in Southwest and Southeast Asia, Colombia, and Mexico. Typically, its color is brownish or white in the form of powder. Black tar heroin is a sticky substance that is obtained from the crude processing method and is illegally sold in the US where it comes from Mexico. Most of the addicts inject, snort, smoke, or sniff heroin [2].

Heroin affects its addicts in many ways: medically, socially, and economically. Medical science reported that as heroin makes entry into the body, it targets brain and receptors on cells, especially those which are responsible for controlling the heart rate, feelings of pleasure and pain, breathing and sleeping [1]. Regarding social perspectives, heroin may disrupt a family, can create panic in a workplace, and may destroy education of an addict, which leads towards crime [3]. Due to high cost of heroin, it has a shocking impact on society and costs billions of dollar each year [4, 5].

Heroin epidemic is known as the spread of heroin addiction in a community or population. Usually, the term epidemic is reserved for the transmission of infectious diseases. However, it is worthy to notice that there are certain situations in which a disorder spreads in a similar way without explicit involvement of the infectious agent. The dynamics of heroin addiction have some familiar characteristics of epidemics, including rapid diffusion and clear geographic boundaries. Therefore, heroin addiction may be treated like an epidemic. From a mathematical point of view, this epidemic has been studied by many researchers [2, 6–10]. A majority of these studies focuses on the derivation of the basic reproduction number \(\mathcal{R}_{0}\) (a number used to measure the transmission potential of a disease) and on the stability of the model around equilibria. Usually, \(\mathcal{R}_{0} < 1\) implies that an epidemic will not result from the introduction of one infected individual and in such cases the epidemic will die out from the community, whereas \(\mathcal{R}_{0} > 1\) implies that an epidemic will occur and will tend to persist in the population in the long run. Whenever the basic reproduction number exceeds one, one must look for control measures in order to overcome the epidemic.

Heroin models comprise an ordinary differential equation; see, e.g., the work of Ma [7], Muroya [11], Wangari [12], and Nyabadza [13] to name only a few. The authors have calculated the basic reproduction number and presented stability analysis therein. Mathematical studies of heroin epidemic via delay differential equations also have an extensive literature. For detail analysis, the readers are suggested to see the work [9, 10, 14–16] and references cited therein. It is worthy to notice that again the authors have focused on the stability analysis of the models concerned under certain conditions.

We are living in a world where each quantity of interest depends on hundreds of variables rather than just one independent variable. Various factors contribute to changes in the dynamics of heroin epidemic. For example, susceptibility of individuals varies significantly during the lifetime of a heroin addict due to the development of the immune system and the change of his lifestyle. The mean elapsed time since heroin initiation is about 20.4 years[17]; therefore, models for heroin addiction should include host demography due to the variability of infectivity. Further, treatment age is also important to be included due to behavioral change of the drug users under treatment. Most importantly, chronological age-structure for heroin addiction should be formulated for better understanding the subject matter, as many characteristics (like contact rate, heroin initiation, etc.) are directly related to an individual’s age. These facts and many more forced some researchers to use partial differential equations (PDEs) to study heroin epidemics via age-structured models. In [18], Fang et al. assumed that susceptibility to addiction of an individual may vary in his lifetime and hence developed and analyzed an age-structured heroin epidemic model. The authors investigated equilibrium of the model and checked for stability conditions. Fang et al. in [19] introduced the concept of treatment age in heroin models, and later on the theory was extended by Yang et al. [20] and Djilali et al. [21] by including different forms of incidence rates. Wang et al. [22] constructed and analyzed a multi-group heroin epidemic model by taking into account both the age of susceptibility and treatment age. Again the authors investigated the model for qualitative aspects and presented some results on the global analysis of the steady states. For a detailed analysis of an age-structured heroin epidemic model, the readers are advised to see the work in [23] and references cited therein.

Like other infectious diseases, heroin addiction is also curable. In order to control heroin use, a variety of effective treatments are available, such as medicines and behavioral therapies. Such medicines include methadone and buprenorphine, etc., whereas behavioral therapies may be contingency management and cognitive-behavioral therapy [1]. However, it is crucial and important to identify which treatment is effective and cheap for controlling heroin addiction. It is more appropriate to start medicine treatment for active heroin addicts, i.e., addicts whose age since initiation of heroin is long enough. On the other hand, behavioral therapy is suggested for those heroin addicts who have small class-age. It is worthy to notice that a majority of the drug users are not seeking treatment. Thus, it will be more appropriate to selectively implement the intervention strategies among the users. Individuals who are affecting others could be removed by techniques such as compulsory closed-ward treatment, immunization with long-acting antagonists like cyclazocide, or, as a last resort, imprisonment. Moreover, by stopping the heroin supply with the help of law enforcing agencies, the addicts will have just one option to stop heroin use and seek addiction treatment.

The work cited above is indeed a great contribution to the field of epidemiology in general and to understanding heroin epidemic in particular; however, there are some points that need to be addressed. Though the authors have included heroin users into treatment, treatment variables (strategies) and its cost etc., were not identified. In other words, the authors studied the dynamical aspect of the treatment class while control strategies were given less attention. Thus, it is more convenient to use optimal control theory which will answer such questions. Further, the inclusion of classes, such as those of heroin users and heroin users in treatment, will make the problem more complex; therefore, it will be more realistic if we include only one class in heroin users that will make it simply an SIR model. After the removal of a treatment factor as a class from the model, one can use the treatment factor as a control variable.

In addition, considering the infection-age (time since heroin initiation) is very important in an epidemic model, particularly in modeling the long-lasting diseases like HIV/AIDS and TB. Once an individual starts heroin use, gradually addiction is developed. As the age of infection progresses, the users face many health issues. The infection-age could affect the dynamics of the susceptible population because contacts of susceptible people with an addict (who uses heroin for a very long time) will infect more susceptible individuals compared to an addict who started using heroin recently. Death related to heroin is directly connected with time since heroin initiation. Further, there is a possibility of fast recovery of addicts whose infection-age is minimal compared to addicts with maximal age of infection. Thus, we shall assume only class-age, namely age since heroin initiation in the heroin user’s’ class. Moreover, people who cease the use of heroin are not included in most age-structured models, however, they were included in case of ODE models as in [12]. The current study aims to include the treatment factor as a control variable in heroin users, including heroin addicts who said goodby to drug-life, and so we present an optimal control problem.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we will develop the model under certain assumptions and will present the existence and uniqueness of a nonnegative solution to the model. The formulation of the control problem and existence of an optimal control will be discussed in Sect. 3. Numerical solution for verification purposes will be carried out in Sect. 4. We will present conclusion of the stdy in the last section of the manuscript.

2 The model

The above-mentioned work on heroin epidemic is indeed a great contribution to the existing literature on the subject matter; however, the majority of referenced material focuses on the three main compartments of the population, namely susceptible, heroin users without treatment, and heroin users with treatment. Further, they have included either treatment-age or susceptibility-age, however, it is more important to consider infection-age (here we refer to the time elapsed since heroin initiation as infection-age) as heroin epidemic may be considered a slowly progressive disease. Moreover, the authors have studied only the dynamical aspects of the developed models and, to the best of our knowledge, there is not a single paper on the control theory of age-structured heroin models. We have formulated an age-structured heroin epidemic model considering infection-age and treatment as a control measure to overcome the spread of heroin. We wish to incorporate another independent variable in the modeling, denoted by a which stand for time since heroin initiation. Thus, we can say that the new dependent variable a is a dynamical variable whose dynamics is given by \(\frac{da}{dt}=1\).

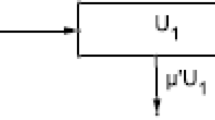

Keeping in view the ideas of [12, 22, 24, 25], we have developed a flow diagram (see Fig. 1) which represents the inflow and outflow of population to each compartment. Based on this flowchart, we captured the problem mathematically in the following model governed by ODEs and a PDE:

The independent variable t is the time, and a denotes the age since heroin initiation. The rest of parameters and variables used in model (2.1) are described as follows:

-

\(S(t)\) represents the susceptible population,

-

\(u(t,a)\) stands for the density of heroin users such that \(\frac{\partial u}{\partial a}\) represents the dynamics of heroin users along infection-age and

$$ U(t)= \int _{0}^{\infty }u(t,a)\,da, $$represents the total population of heroin addicts at time t,

-

\(R(t)\) denotes the population who ceased the use of heroin,

-

μ is the natural mortality rate,

-

Λ is the recruitment rate (new individuals coming to the population, whether by birth or by immigration),

-

δ denotes the heroin-induced removal rate,

-

\(\xi (a)\) is the age-specific self-cure (users who cease using heroin by self-decision) rate,

-

\(\sigma (a)\) denotes the age-specific transmission rate.

We have imposed certain assumptions on the model that include:

-

Within the modeling time period, the whole population \(N(t)=S(t)+\int _{0}^{\infty }u(t,a)\,da+R(t)\) is assumed to be constant.

-

Only active heroin users are infectious to susceptibles.

-

Homogenous mixing assumption is true for the model under consideration.

-

The fraction of addicts who cease using heroin may be vulnerable to start using heroin again.

The parameters of the model will obey the following conditions:

C1. \(\Lambda ,\mu ,\delta>0\), and \(\xi (a)\) is a continuous positive function.

C2. \(\sigma (a)\in L_{+}^{\infty }\) with an essential upper bound σ̄.

C3. \(\sigma (a)\) is Lipschitz continuous on \(\mathbb{R}_{\geq 0}\), with Lipschitz coefficient \(M_{\sigma }\).

Further, we introducing some notations for the sake of simplicity:

The solutions of equation (2.1b) may be obtained by using the method of characteristics in the following form:

Integrating (2.1a), (2.1c), and considering relation (2.2) along with the conditions, we get the following system of equations:

A direct application of theorems related to fixed-points from [26], it is handy to show that system (2.3) has a nonnegative solution in the interval \([0,\infty )\).

The desired functional space for system (2.1) is considered in the following form:

Here, \(L_{+}^{1}\) represents the space of those functions which are Lebesgue-integrable and nonnegative on \([0, \infty )\). Such a space of functions is equipped with the norm

It is to be noted that a physical interpretation of the norm is the size of the total population. Similarly, we can write the initial conditions of the model (2.1) as

In light of conditions \(C_{1}\)–\(C_{3}\), the existence and uniqueness theorems suggest that model (2.1) has a unique nonnegative solution under the additional condition \(\mathcal{Z}_{0} \in \mathcal{Z}\). Further, a continuous semiflow \(\chi :R_{+}\times \mathcal{Z} \rightarrow \mathcal{Z}\) is defined by system (2.1), and solutions have a nonempty omega-limit sets because of compact closure [27].

3 Optimal control strategies

Optimal control theory and calculus of variations are the two main techniques used for exploring a control law for a model with some predetermined objectives. For problems lying in infinite-dimensional spaces, one can apply the technique of calculus of variations, however, this technique is not dynamic. As the problem under consideration is stated in an infinite-dimensional space, we will apply optimal control theory since it is dynamic. As suggested in [24], we will use the maximum principle type results introduced by Li and Yong [28].

The proposed model has three state variables, \(S(t)\), \(U(t)\), and \(R(t)\), and a single control variable, \(v(t)\), from an admissible control set \(V_{ad}= \{v \in L^{2}(0,T)|0 \leq v(t) \leq l \leq 1 ,t \in [0,T] \}\). The physical interpretation of the control v is that of treatment of a heroin addict with medicines. Since we are treating heroin users, the term \(v(t)u(t,a)\) will be subtracted from equation (2.1b), whereas \(v(t)\int _{0}^{\infty }u(t,a)\,da\) will be added to equation (2.1c) in model (2.1). We shall assume that upon treatment of a heroin user, the individual will get a permanent immunity from heroin addiction. The case \(v(t)=0\) means no treatment, whereas \(v(t)=1\) will reflect the fact the all heroin users are treated. Usually, the cost on treatment depends quadratically on treatment rate [29, 30], thus, we will analyze a quadratic term for the control variable. Such objective functionals are very common in practice, for instance, one can see that our objective functional is a special case of that in [31] by setting \(L(t)=0\). Furthermore, our aim in the current work is to minimize the number of heroin users and to maximize the groups of susceptible and recovered individuals. The objective functional will take the form

subject to

Here \(B>0\) is called a balancing factor and it represents the level of acceptance of an addict to treatment. In the following theorem, we will prove that there exist an optimal control variable which minimizes the objective functional.

Theorem 3.1

There exists a control variable \(v^{\star }\in V_{ad}\)that minimizes the objective functional \(J(v)\)subject to system (3.1).

Proof

Clearly, the admissible control set \(V_{ad}\) is convex and closed. Further, solutions of the controlled system are bounded, which implies the compactness of the controlled system. The property of compactness of the controlled system is necessary for the existence of an optimal control variable. In addition, on the admissible set the integrand in \(J(v)\) is a convex function. Moreover, there exists \(\zeta \in R_{+}>1\) and \(\eta _{1},\eta _{2}\in R_{+}\) such that

As all of the hypothesis of Theorem 13.8.1 in [32] are satisfied by \(V_{ad}\) and \(J(v)\), there exists an optimal control for the problem. □

For obtaining the necessary conditions, let introduce another control \(v^{\epsilon }(t)= v(t)+ \epsilon h(t)\) where ϵ is between 0 and 1, and \(h(t)\) is called a variation function. The function h may be positive or negative in such a way that \(v^{\epsilon }\) still belongs to V. Since the state variables depend on v, accordingly the state variables will take the form \(S^{\epsilon }= S(v^{\epsilon })\), \(U^{\epsilon }= U(v^{\epsilon })\), \(R^{\epsilon }= R(v^{\epsilon })\). In the same way, system (3.1) can be written in the following form correspond to the new control variable:

Next, we will subtract system (3.1) from (3.4) to get the difference quotients \(\frac{S(v+\epsilon h)-S(v)}{\epsilon }\), \(\frac{u(v+\epsilon h)-u(v)}{\epsilon }\), and \(\frac{R(v+\epsilon h)-R(v)}{\epsilon }\) called the weak or Gateaux derivatives. The sensitivities \(\bar{S}(t)\), \(\bar{u}(t,a)\), and \(\bar{R}(t)\) could be obtained by applying \(\lim_{\epsilon \rightarrow 0}\) to the weak derivatives. These sensitivities will satisfy the following linearized version of system (3.1):

In the same way, the Gateaux derivative of \(J(u)\) becomes

where \(\bar{U}(t)=\int _{0}^{\infty }\bar{u}(t,a)\,da\). The sensitivities’ equations in (3.5) can be used for obtaining the adjoint equations. In order to obtain the adjoint system, we will first consider equation (3.5a) as

with the conditions

Here \(\langle f_{1},f_{2} \rangle =\int _{0}^{T}f_{1}f_{2}\,dt\) and \(\langle \langle f_{1},f_{2} \rangle \rangle =\int _{0}^{T}\int _{0}^{\infty }f_{1}f_{2}\,da\,dt\). Equation (3.5b) can be written in the form of

with the conditions

Similarly, equation (3.5c) can be written as

with

Collecting equations (3.7), (3.9), and (3.11) with subsidiary conditions and by rearranging the terms, we get the following adjoint system:

with the transversality conditions

Theorem 3.2

If \(v^{\star }\)in \(V_{ad}\)is an optimal control which minimizes \(J(v)\)and \((S^{\star }(t), U^{\star }(t), R^{\star }(t))\)and \((\lambda _{1}(t), \lambda _{2}(t,a), \lambda _{3}(t))\)are the corresponding state and adjoint variables, then

Proof

By using system (3.13), we can write relation (3.6) as

By considering equations (3.7), (3.9), and (3.11), we can write equation (3.16) as

Considering the case of \(h(t)\ne 0\) on \(V_{ad}\), the rest of the integrand must be equal to zero. Hence

Assuming the upper and lower bounds of v, we have

which is the required characterization of the optimal control. □

It is to be noted that the desired optimal control variable lies within the bounds stated earlier. Thus, our optimal control problem takes the following form:

with \(v^{\star }(t)\) defined in equation (3.18).

4 Numerical simulations

Though analytically we have obtained an optimal system (3.19) from the given system (3.1), the optimality and effectiveness of the control variable need to be verified numerically. For this purpose, we will present some sample simulations in the present section. Since the problem under discussion contains ODEs and a PDE equation, we will use the finite difference method. This method is very easy to apply and best suited for implementation on a computer algebra system. Next, we will consider the same step size \(\Delta t=\Delta a\). Further, we assumed that \(S(t_{n})\approx S_{n}\), \(u(t_{n},a_{i}) \approx u_{i}^{n}\), \(R(t_{n}) \approx R_{n}\) for each time point \(t_{n}\) and class-age \(a_{i}\). Following the same procedure presented in [33], we obtained the following numerical scheme for the proposed model:

Here, the method is convergent with order of convergence \({\Large O}(\Delta t)\) and approximations of the solution converging to the true solution as \(C\Delta t \rightarrow 0\) whenever \(t \rightarrow 0\), where C is an appropriate constant. Any numerical method is acceptable if it is convergent at least of order \({\Large O}(\Delta t)\).

Here \(n=0,\dots ,N-1\) and \(i=0,\dots ,K-1\), where N and K are the maximum numbers of points of time and class-age, respectively. Similarly, the adjoint system and the optimal control variable were coded in MATLAB using the same technique. It is important to discretize the whole domain with a discrete square mesh. For this purpose, we will discretize the age and time directions. Since both age and time progress simultaneously, we discretized the age and time with the same step \(\Delta t=0.05\). The initial population and age-distribution of all classes were assumed in light of the assumptions on the model. The values of parameters and their justification are presented in Table 1. The age since heroin initiation is assumed to be 40 years, where the treatment period is 40 days.

The authors in [13] have estimated the range for Λ to be 0.04–0.028 in terms of per 100 individuals. Thus our assumption of \(\Lambda =18\) makes sense as we are dealing with population rather than density. The value of the transmission rate β in [20] was considered to be constant and equal to 0.03. Here, we assume that the transmission rate is not constant; in fact, it depends on the time since heroin initiation, i.e., \(\sigma (a)=0.03e^{-a}\). Choosing this particular shape of \(\sigma (a)\) will cover the value of \(\beta =0.03\) as a special case when we set \(a=0\). Further, an individual who is using heroin for a very long time will definitely face many health issues and thus his contact with susceptibles will become weak. This fact was mathematically captured in the term \(e^{-a}\). Similarly, we assumed the value of age-specific self-cure rate to be \(\xi (a)=0.5e^{-a}\) as it contains the choice of ξ in [12] as a special case when \(a=0\). In addition, the authors claiming that for an individual whose infection-age tends to increase, his/her intention to cease the use of heroin will surely get diminished and this claim was mathematically captured in the form of \(e^{-a}\).

Figure 2(a) represents the population of people who are susceptible to heroin use. The figure indicates that the control is very effective, especially in the final course of treatment. In the initial 5 days of the control program, a negligible effect of the control could be observed on the susceptible population; afterwards the susceptible population with control tends to increase at a faster rate in comparison to \(S(t)\) without control which is declining and approaching a steady state. Figures 2(b) and 2(c) represent the density of heroin users without and with control, respectively. To present a possible interpretation of these figures, we have plotted some sample curves from Figs. 2(b) and 2(c) (at fixed ages a) in Figs. 3(a) and 3(b), respectively. Figure 2(b) along with Fig. 3(a) suggests that the population density of heroin users with infection-age \(a\leq 10\) will tend to decline and reach to a stable point \(u^{*}\geq 0.0325\) within a maximum time of 10 days. Heroin users with low infection-age will tend to stabilize fast; however, the value of stabilization points tends to decrease by increasing the time since heroin initiation. Similarly, Figs. 2(c) and 3(b) show that by implementing the control policy, the population irrespective of its infection age stabilizes itself again to a value \(u^{*}\leq 0.22\) in the long run. A population whose class-ages are greater or equal to 3.5 years tends to vanish approximately after 3.8 days for a specific period whose length depends on the infection-age. Afterwards the population tends to increase again and asymptotically approaches a value less than or equal to 0.057. Here one can observe that the control program will stabilize the population density of heroin users (whose infection-age is smaller) to a nonrivial value in comparison to addicts (whose infection age is higher) which approaches zero soon after the implementation of the control program.

In Figs. 4(a), 4(b), and 4(c), we compared sample solution profiles of \(u(t,a)\) with and without control at a fixed infection-age a. These figures depict that the control is highly effective for the heroin users whose class-age is less than 15 years, whereas the control shows a moderate effect on heroin users whose class-age is from 15 to 25 years. Initially, the treatment has a good effect on addicts who use heroin for more than 30 years as well, however, after 35 days the curves for cases with and without control behave similarly. This fact is realistic as well because active heroin users are showing ignorance to such a treatment. This means that the treatment shows good outcomes irrespective of infection-age with inverse dependency.

The same argument was supported by Figs. 5(a), 5(b), and 5(c), in which we have chosen some curves from the density function \(u(a,t)\) at a fixed time both with and without control cases. The figures depict that an initial population of heroin users is distributed in such a way that individuals with low and high infection age are higher compared to people with middle infection ages. As the time progresses, a remarkable decrease could be observed in the heroin users irrespective of their infection age, and finally the population of heroin users whose infection age is greater than or equal to 30 vanishes in the long run. Referring to Fig. 3(b), we can say that when \(4\leq t\leq 10\) days, we have no heroin users whose age is above 5 years. With the progression of the control program, we have only heroin users whose infection-age is less than or equal to 30 years, and the density of addicts who use heroin for the past 30 years has completely vanished with the successful implementation of the control program. The figure shows that in the initial stages of the control more heroin users tend to cease the use of heroin. However, as the treatment time progresses, the control affects less and less heroin users irrespective of their class-age. Figure 2(d) shows that the treatment effects the recovered population as well, however, due to relapse the recovered population is again vulnerable to the use of heroin and thus it goes back to the susceptible compartment. In Fig. 6(a), we plotted the optimal objective functional, as well as objective functional without optimal values of the state and control variables. The plot shows that the values attained by the objective functional are realistic and optimal. The dynamics of the objective functional suggest that a remarkable difference may be noticed as time evolves. Similarly, Fig. 6(b) depicts the dynamics of the control variable, which shows that the control is effective in the initial 10 days of the control program. Afterwards the control variable tends to decrease and eventually vanishes.

Keeping in mind Fig. 5, we can say that soon after the implementation of the control program, heroin users with low infection-age start to cease using heroin. In the middle of the control program, heroin users with moderate and high infection-age show reaction and they are planing to quit using heroin. It is also worthy to notice that the control slightly disturbs the dynamics of people who are using heroin for a long time. The people who cease the use of heroin, start taking the drug again due to susceptibility again. Thus, it is more appropriate to reduce the relapse rate by using another control for the recovered population on which the authors will work in the future.

5 Conclusion

In the present work, we have discussed a heroin epidemic model with some predetermined objectives. Recognizing the impacts of heroin on people first, diagnosing its proper treatment and its effects on the society are the key objectives of this work. Besides time, we have considered class-age (age since heroin initiation) only in the heroin addict compartment. We have developed a control problem and analyzed it for further discussion. The weak derivatives and sensitivities were used for obtaining an optimal control problem. The effect of treatment was investigated during simulation. We infer from the findings that the heroin users with a small class-age show great improvement/effects with proper treatment/diagnoses.

Prevention should always go first because it is the most cost-effective, and we must look for the most effective way to deal with the illicit drug problem. The final outcomes of such drugs primarily depend upon the number of users, their sources, spreading of the habit, and on the state of mind, as well as on the size of the vulnerable population. Therefore, it is critical to look for different intervention strategies and chose the most cost-effective and best control policy. Further, treatment plans should be individualized to meet the needs of the patients. This model includes different treatment options for heroin users with diverse infection-age which will definitely help the policy makers in the implementation of any treatment program.

We studied here only the spread pattern of heroin epidemic both with and without treatment at various stages of the addiction. Whenever the tendency to use heroin is high, early treatment could be vital; if treatment is late, its effect becomes smaller until a point is reached when, to be effective, treatment has to be on a huge scale. Early action is the most effective, but there is a position ahead of which action is too small to affect the result significantly.

References

NIDA: “Heroin.” National Institute on Drug Abuse, 27 Jun. 2019, https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/heroin. Accessed 21 Sep. 2019

White, E., Comiskey, C.: Heroin epidemics, treatment and ODE modelling. Math. Biosci. 208, 312–324 (2007)

Ritter, A., Phuong Hoang, V., Cao, V.L., Shanahan, M., Shukla, N., Perez, P., Farrell, M.: Modelling heroin careers over 40 years: social costs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 171, e177 (2017)

Walsh, J.M.: Are we there yet? Measuring progress in the U.S. war on drugs in Latin America. Washington Office on Latin America. Drug War Monitor, 1–6 (2004)

Hagemeier, N.E.: Introduction to the opioid epidemic: the economic burden on the healthcare system and impact on quality of life. Am. J. Manag. Care 24, S200–S206 (2018)

Mulone, G., Straughan, B.: A note on heroin epidemics. Math. Biosci. 218, 138–141 (2009)

Ma, M., Liu, S., Li, J.: Bifurcation of a heroin model with nonlinear incidence rate. Nonlinear Dyn. 88, 555–565 (2017)

Mushanyu, J., Nyabadza, F., Muchatibaya, G., Stewart, A.G.R.: Modelling multiple relapses in drug epidemics. Ric. Mat. 65, 37–63 (2016)

Fang, B., Li, X., Martcheva, M., Cai, L.: Global stability for a heroin model with two distributed delays. Discrete Contin. Dyn. Syst. 19, 715–733 (2014)

Samanta, G.P.: Dynamic behaviour for a nonautonomous heroin epidemic model with time delay. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 35, 161–178 (2011)

Muroya, Y., Li, H., Kuniya, T.: Complete global analysis of an SIRS epidemic model with graded cure and incomplete recovery rates. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 410, 719–732 (2014)

Wangari, I.M., Stone, L.: Analysis of a heroin epidemic model with saturated treatment function. J. Appl. Math. 21, 1953036 (2017)

Nyabadza, F., Hove-Musekwa, S.D.: From heroin epidemics to methamphetamine epidemics: modelling substance abuse in a South African province. Math. Biosci. 225, 132–140 (2010)

Liu, J., Zhang, T.: Global behaviour of a heroin epidemic model with distributed delays. Appl. Math. Lett. 24, 1685–1692 (2011)

Huang, G., Liu, A.: A note on global stability for a heroin epidemic model with distributed delay. Appl. Math. Lett. 26, 687–691 (2013)

Liu, X., Wang, J.: Epidemic dynamics on a delayed multi-group heroin epidemic model with nonlinear incidence rate. J. Nonlinear Sci. Appl. 9, 2149–2160 (2016)

Darke, S., et al.: Patterns and correlates of attempted suicide amongst heroin users: 11-year follow-up of the Australian treatment outcome study cohort. Psychiatry Res. 227(2–3), 166–170 (2015)

Fang, B., Li, X., Martcheva, M., Cai, L.: Global stability for a heroin model with age-dependent susceptibility. J. Syst. Sci. Complex. 28, 1243–1257 (2015)

Fang, B., Li, X., Martcheva, M., Cai, L.: Global asymptotic properties of a heroin epidemic model with treat-age. Appl. Math. Comput. 263, 315–331 (2015)

Yang, J., Li, X., Zhang, F.: Global dynamics of a heroin epidemic model with age structure and nonlinear incidence. Int. J. Biomath. 9(3), 1650033 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1142/S1793524516500339

Djilali, S., Touaoula, T.M., Miri, S.E.H.: A heroin epidemic model: very general non linear incidence, treat-age, and global stability. Acta Appl. Math. 152, 171–194 (2017)

Wang, J., Wang, J., Kuniya, T.: Analysis of an age-structured multi-group heroin epidemic model. Appl. Comput. Math. 347, 78–100 (2019)

Liu, L., Liu, X.: Mathematical analysis for an age-structured heroin epidemic model. Acta Appl. Math. 164, 193–217 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10440-018-00234-0

Khan, A., Zaman, G.: Optimal control strategy of SEIR endemic model with continuous age-structure in the exposed and infectious classes. Optim. Control Appl. Methods 39, 1716–1727 (2018)

Zaman, G., Saito, Y., Khan, M.: Optimal vaccination of an endemic model with variable infectivity and infinite delay. Z. Naturforsch. 68a, 677–685 (2013)

Grippenberg, G., Londen, S.O., Staffans, O.: Volterra Integral and Functional Equations. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1990)

Webb, G.F.: Theory of Nonlinear Age-Dependent Population Dynamics. Marcel Dekker, New York (1985)

Li, X., Yong, J.: Optimal Control Theory for Infinite Dimensional Systems. Birkhäuser, Boston (1995)

Martcheva, M.: Control strategies. In: An Introduction to Mathematical Epidemiology. Texts in Applied Mathematics, vol. 61, p. 238. Springer, Boston (2015)

Neilan, R.M., Lenhart, S.: Optimal vaccine distribution in a spatiotemporal epidemic model with an application to rabies and raccoons. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 378, 603–619 (2011)

Rahman, G.U., Agarwal, R.P., Liu, L., Khan, A.: Threshold dynamics and optimal control of an age-structured giving up smoking model. Nonlinear Anal., Real World Appl. 43, 96–120 (2018)

Lukes, D.L.: Differential Equations: Classical to Controlled, Mathematics in Science and Engineering. Academic Press, New York (1982)

Martcheva, M.: Age-structured epidemic models. In: An Introduction to Mathematical Epidemiology. Texts in Applied Mathematics, vol. 61. Springer, Boston (2015)

Thater, M., Chudej, K., Pesch, H.J.: Optimal vaccination strategies for an SEIR model of infectious diseases with logistic growth. Math. Biosci. Eng. 15(2), 485–505 (2017)

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks to Dr. Majid Khan, University of Science and Technology China, and Dr. Wajaht Ali Khan, University of Malakand, Pakistan, for their diligent proofreading and improving the final version of the manuscript. The first author is supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the central Universities (No. 20lgpy137).

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (11971493).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

We declare that all the authors read and verified the manuscript, and equally contributed towards the structure of the article, it’s design, and coordination of the study done. The authors further approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Din, A., Li, Y. Controlling heroin addiction via age-structured modeling. Adv Differ Equ 2020, 521 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-020-02983-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-020-02983-5