Abstract

This study systematically reviewed and synthesized the literature on psychological and clinical outcomes of receiving a variant of uncertain significance (VUS) from multigene panel testing or genomic sequencing. MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched. Two reviewers screened studies and extracted data. Data were synthesized through meta-analysis and meta-aggregation. The search identified 4539 unique studies and 15 were included in the review. Patients with VUS reported higher genetic test–specific concerns on the Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment (MICRA) scale than patients with negative results (mean difference 3.73 [95% CI 0.80 to 6.66] P = 0.0126), and lower than patients with positive results (mean difference −7.01 [95% CI −11.31 to −2.71], P = 0.0014). Patients with VUS and patients with negative results were similarly likely to have a change in their clinical management (OR 1.41 [95% CI 0.90 to 2.21], P = 0.182), and less likely to have a change in management than patients with positive results (OR 0.09 [95% CI 0.05 to 0.19], P < 0.0001). Factors that contributed to how patients responded to their VUS included their interpretation of the result and their health-care provider’s counseling and recommendations. Review findings suggest there may be a need for practice guidelines or clinical decision support tools for VUS disclosure and management.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Multigene panel testing and genomic sequencing (exome or genome sequencing) are increasingly used in place of single-gene tests across multiple spheres of care, including cancer and cardiology. Such tests greatly increase the number of variants identified when compared with single-gene tests, increasing the likelihood of identifying a variant of uncertain significance (VUS). VUS are genetic variants with limited or conflicting evidence to support their pathogenicity or lack thereof, which cannot be classified as pathogenic or benign.1 The yield of VUS from multigene panel testing and genomic sequencing is substantial. For instance, in one study, 36% of patients who received multigene panel testing were found to have VUS,2 and others have found that as many as 73% of patients who received exome sequencing had VUS.3 VUS may be reclassified over time as new evidence becomes available. While the majority are downgraded to benign or likely benign, a minority are reclassified as likely pathogenic or pathogenic.4,5,6 As VUS have uncertain implications, it is typically recommended that patients with VUS are managed based on their personal and family history, rather than on the test result,7 but this may not always be the case.8

Evidence on patients’ psychological and clinical outcomes after receiving a VUS is conflicting. Some research suggests that patients who receive a VUS experience heightened anxiety following return of results,9 while other research has not found increased distress among patients with VUS.10 Similarly, some research has found a higher rate of risk-reducing surgery among patients with VUS than among patients with negative results,11 whereas others have found no difference in the rate of surgery between those who receive VUS and those who receive negative results.8

Evidence synthesis, such as a systematic review, can be useful when studies on the effect of an intervention have conflicting findings,12 as is the case with outcomes of receiving a VUS. To our knowledge, no prior evidence synthesis has been conducted that examines the clinical and psychological outcomes after return of VUS specifically from multigene panel testing and genomic sequencing. This study aimed to systematically review and synthesize quantitative and qualitative literature to evaluate psychological and clinical outcomes after the receipt of a VUS from multigene panel testing or genomic sequencing, and to identify factors that contribute to shaping patients’ psychological and clinical responses to a VUS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A systematic review was conducted to identify and synthesize data from quantitative and qualitative studies relevant to the study aim. The protocol for this review was submitted to PROSPERO in April 2018 and is registered as CRD42018093737. Preparation of this paper was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items in Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)13 reporting checklist.

Study selection criteria

Population

Studies were included if the population included adults who received multigene panel testing, exome sequencing, or genome sequencing to diagnose or assess their personal risk for a hereditary disorder. Studies were excluded if patients received only single-gene or BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing. Studies of adults receiving prenatal testing were excluded, as were studies in which all participants were parents whose child received testing. Postmortem studies were excluded. When needed, study authors were contacted to clarify whether their paper met inclusion criteria.

Intervention

The intervention of interest was receipt of a VUS (without any pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants). Studies were included if all or a portion of participants had received a VUS and excluded if none received a VUS.

Comparator

Comparator groups were patients who received either a negative (no variant reported) or positive (pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant reported) result. If studies included participants who received a pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant as well as a VUS, those participants were considered to have a positive result, consistent with how these participants were reported on in the original studies. Studies without comparator groups were included (e.g., qualitative studies in which all participants had VUS).

Outcomes

Studies were included if they reported data on at least one of the following outcomes:

-

1.

Psychological outcomes (e.g., distress) following return of results, reported through quantitative or qualitative data

-

2.

Clinical outcomes (e.g., changes in clinical management, such as surveillance or surgery) following return of results, reported through quantitative or qualitative data

-

3.

Patients’ interpretation of their VUS, reported through qualitative data

Studies

Experimental studies, quasi-experimental studies, observational studies, qualitative studies, and case series were eligible for inclusion. Systematic reviews were excluded. Commentaries, animal studies, conference abstracts, single case reports and non-English articles were excluded.

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed by a professional librarian (E.U.) in consultation with C.M. The search strategy included both MeSH subject headings and text word terms for clinical sequencing and VUS (Appendix 1). Medical genetics journals and the reference lists of included studies were hand searched by C.M. Gray literature was not searched, nor were trial registries.

Information sources

A systematic, comprehensive search of Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Medline-in-Process, Medline Epubs Ahead of Print, and Embase Classic+Embase databases (OvidSP) was run by a professional librarian (E.U.) on 7 March 2018. There was no date limit on the search.

Selection of studies

References were imported to Covidence software (http://covidence.org). Due to the large volume of articles identified by the search, one reviewer (C.M.) initially screened all articles by title. Articles that clearly did not meet inclusion criteria were excluded (e.g., studies of animal models). Following title screening, two independent reviewers (C.M. and S.S.) conducted abstract and full-text screening. Reasons for exclusion were reported. Conflicts were resolved through discussion.

Data extraction

C.M. and S.S. independently extracted data from all studies, and subsequently compared the extracted data for consistency and to resolve discrepancies. Data was extracted on bibliographic information, study characteristics (e.g., design, country, year), participant characteristics (e.g., recruitment criteria, disease population, age, sex), genetic test characteristics (e.g., genes tested, type of test), and data relevant to the review’s outcomes of interest. For studies that reported psychological outcomes on scales, data from all scales were extracted. Data extraction forms were piloted prior to data extraction. Quantitative data were extracted in Covidence using a standardized form. For qualitative data, findings relevant to the review’s outcomes of interest were extracted14 using a standardized template in Excel. Further detail about qualitative extraction is provided below.

Assessment of quality of studies

The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools for qualitative studies, cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, and case series were used.15 Quality assessment was conducted independently by C.M. and S.S., and compared. Studies were not excluded based on quality. Results of the quality assessment were reported in aggregate for each study design.

Data synthesis

Data synthesis of quantitative and qualitative data followed an integrative approach16 such that results were synthesized descriptively and, where possible, through meta-analysis.

Synthesis of quantitative data

Study characteristics, patient characteristics, genetic test characteristics, and outcome data were descriptively reported. Quantitative results were synthesized through fixed-effect meta-analysis. Random-effects meta-analysis, which produces a summary effect estimate that can be generalized to other populations, was originally planned, but was not possible because too few studies were included in the review.17 Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic, which was calculated separately from the fixed-effect analysis and not incorporated in the model.17

For psychological outcomes, meta-analyses of two scales were conducted. For the first set of meta-analyses, studies were included if they reported participants’ scores on the Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment (MICRA) or an adapted version of the MICRA for different disease populations, and reported results for patients with positive results, negative results, and VUS. The MICRA was developed for genetic testing for cancer and measures the multidimensional impact of learning genetic risk information, including uncertainty, distress, and positive experiences.18 As the MICRA was developed for use in the context of genetic testing, it confers greater sensitivity than general distress measures to capture genetic test-specific concerns.18 Higher scores on the MICRA indicate higher levels of genetic test–specific concerns. For studies that reported outcomes for patients with and without a personal disease history separately, pooled means and standard deviation (SDs) were calculated for each result type so that three groups were included in the analysis: positive result, negative result, and VUS. One study reported the 95% confidence interval (CI) rather than SD; the 95% CI was used to calculate SD.19 One meta-analysis was conducted to compare MICRA scores for patients with negative results and patients with VUS, and a second meta-analysis was conducted to compare MICRA scores for patients with positive results and patients with VUS.

For the second set of meta-analyses of psychological outcomes, studies that reported psychological outcomes on the Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R) for patients with positive results, negative results, and VUS were included. The Impact of Events Scale-Revised measures symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), with subscales to capture hyperarousal, intrusion, and avoidance.20 Higher scores on the IES-R indicate higher levels of distress. One meta-analysis was conducted to compare IES-R scores for patients with negative results and patients with VUS, and a second meta-analysis was conducted to compare IES-R scores for patients with positive results and patients with VUS. The summary measure of this meta-analysis was mean difference in IES-R score between groups (VUS compared with positive result, and VUS compared with negative result).

For the meta-analyses of changes in clinical management across studies, studies were included in if they reported the proportion of patients whose clinical management changed after receiving their genetic test result or the proportion of patients who received specific procedures after receiving their genetic test result (e.g., surgery), for patients with positive results, negative results, and VUS. If a study reported data for patients with and without a personal history of disease separately, data were pooled so that there were three comparison groups for each study: positive result, negative result, and VUS. One meta-analysis was conducted to compare the proportion of patients whose clinical management changed based on their genetic test result between patients with negative results and patients with VUS, and a second meta-analysis was conducted to compare changes in management between patients with positive results and patients with VUS. The summary measure of the meta-analysis was the odds ratio (OR) of a change in clinical management (VUS compared with positive result, and VUS compared with negative result).

For each meta-analysis, statistical significance was assessed at the P < 0.05 level. Forest plots were constructed for each meta-analysis to display individual study results, the weights of each study, and the overall weighted estimates with 95% CI. All meta-analyses were performed in R Studio (version 1.2.5033).

Synthesis of qualitative data

A meta-aggregative approach was used to synthesize qualitative data.14 Meta-aggregation is a pragmatic approach to qualitative evidence synthesis that allows for the combination of findings from studies included in the review, as opposed to reconceptualization or reinterpretation as would be done in a realist synthesis or meta-ethnography.14 Meta-aggregation focuses on synthesis of study findings (i.e., the original study authors’ interpretation of the data) with the key underlying assumption that if multiple studies report on the same phenomena, their findings can be combined, regardless of study methodology (e.g., phenomenology, grounded theory).21 In this review, all included studies reported on the same phenomenon of interest, participants lived experience of receiving a VUS, and it was therefore deemed possible for findings to be pooled. Text that reported themes relevant to the review’s outcomes of interest was extracted verbatim from included studies, along with supporting quotations from participants reported in the original study.14 Findings were then compared across studies, and findings related to similar concepts were grouped into categories.14 Categories were then assembled into conceptually similar groups, or “synthesized findings.”14

Changes from original protocol

The original protocol registered on PROSPERO included communication of VUS to relatives as an outcome of the study. It was subsequently decided that the scope of the review was too broad, and this outcome was not included in the final review.

RESULTS

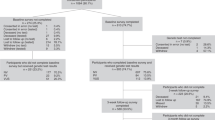

The complete search strategies and number of articles retrieved are listed in Appendix 1. A total of 7144 references were retrieved, 2604 of which were duplicates. Handsearching identified one article not captured by the search. After removing duplicates, 4539 articles were screened by title and 3910 excluded (Fig. 1). Six hundred twenty-nine articles were screened by abstract, and 459 excluded. One hundred seventy articles were retrieved for full-text review. In total, 155 were excluded for the following reasons: participants had not received panels or sequencing (79 articles), outcomes of interest were not reported (27 articles), no participants in the study received a VUS (21 articles), the study design did not match inclusion criteria (e.g., systematic reviews, commentaries; 15 articles), the study population did not match the review’s inclusion criteria (e.g., all participants were parents or were receiving prenatal testing; 13 articles), or the article was not in English (1 article). Fifteen studies were included in the final review (Table 1).22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36

Characteristics of included studies

Ten of the 15 studies were quantitative designs22,23,25,26,27,28,30,31,32,36 and 5/15 were qualitative.24,29,33,34,35 In 2/15 articles, patients received exome sequencing,28,34 and in 13/15 they received multigene panels.22,23,24,25,26,27,29,30,31,32,33,35,36 The majority of the studies (10/15) were conducted among hereditary cancer patients. Sample size ranged from 16 to 666, for a total of 1968 patients, and the number of patients who received a VUS ranged from 3 to 79. The majority of patients were aged 40 or older on average and were female (1446 reported, 73.5%) (Table 1). Six of the ten quantitative studies reported data on psychological outcomes (Table 2) and seven reported clinical outcomes (Table 3).

Overview of findings

Findings from quantitative and qualitative studies were analyzed separately; findings from the qualitative studies may shed light on the quantitative results. Meta-analysis of quantitative studies’ findings identified that patients with VUS reported higher levels of genetic test–specific concerns on the MICRA than patients with negative results, but they reported lower concerns than patients with positive results. Synthesis of qualitative studies’ findings identified various factors that shaped patients’ psychological responses to their VUS, including patients’ interpretation of the VUS (e.g., as disease-causing, uncertain, or not disease-causing), whether their health-care provider prepared them to receive a VUS, and the context in which they received genetic testing. From the meta-analysis of quantitative data, patients with VUS and patients with negative results were equally likely to undergo changes in their clinical management following return of results. However, in a minority of cases, changes in clinical management were made on the basis of VUS. Synthesis of qualitative studies’ findings identified factors that contributed to variation in how patients acted on their VUS. These included patients’ interpretation of the result (e.g., as a health threat or not) as well as their health-care provider’s interpretation and recommendations.

Patients with VUS reported higher concerns than patients with negative results, but no difference in distress

Meta-analysis of MICRA scores approximately 1 year after return of results showed that MICRA scores for patients with VUS were higher than scores reported by patients with negative results (mean difference 3.73 [95% CI 0.80 to 6.66], P = 0.0126, I2 = 41.77%, Fig. 2a), but lower than scores reported by patients with positive results (mean difference -7.01 [95% CI -11.31 to -2.71], P = 0.0014, I2 = 42.32%, Fig. 2b); both differences were statistically significant.25,30,36 This indicates that patients who received VUS experienced higher levels of genetic test–specific concerns than patients with negative results, but lower levels of genetic test–specific concerns than patients with positive results.

(a,b) Meta-analyses of Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment (MICRA) scores. MICRA scores were statistically significantly higher among patients with variants of uncertain significance (VUS) than among patients with negative results. MICRA scores were statistically significantly lower among patients with VUS than among patients with positive results. (c,d) Meta-analyses of Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R) scores. There was no statistically significant difference in IES-R scores between patients with VUS and patients with negative results. MICRA scores were statistically significantly lower among patients with VUS than among patients with positive results. (e,f) Meta-analyses of changes in clinical management. Patients with VUS and with negative results were similarly likely to have a change in their clinical management. Patients with VUS were less likely to have a change in their management than patients with positive results. FE fixed-effect.

Meta-analysis of the IES-R across the same three studies25,30,36 identified that there was no statistically significant difference in IES-R scores reported by patients with VUS and patients with negative results (mean difference -1.42, 95% CI -4.02 to 1.19, P = 0.29, I2 = 0.00%, Fig. 2c). Patients with VUS reported lower event-specific distress than patients with positive results (mean difference -5.57, 95% CI -9.38 to -1.75, P = 0.004, I2 = 37.72%), which was statistically significant (Fig. 2d). This indicates that patients with VUS experienced less distress than patients with positive results, and similar levels of distress to patients with negative results.

Two studies that reported psychological outcomes were not included in the meta-analysis because they did not include the MICRA or IES-R scales,23,28 or did not include a non-VUS comparator group.28 Data reported on psychological outcomes from these studies can be found in Table 2.

Psychological responses varied based on preparation, context, and interpretation of the VUS

Meta-aggregation of the findings from the qualitative studies revealed that patients’ psychological responses varied based on their preparation to receive a VUS, the context in which they received their result, and their interpretation of their VUS. For instance, patients whose health-care provider had not informed them about the possibility of receiving an uncertain result before they had testing reported that they experienced shock when they received their VUS;35 those whose health-care provider prepared them for the possibility of receiving an uncertain result in their pretest counseling did not report shock to receive a VUS.34

The context in which patients received genetic testing also played a role in shaping psychological responses.24,35 For example, for some patients, their clinical diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy was more shocking and distressing than the VUS.24 Another participant reported being overwhelmed to learn of a VUS while undergoing cancer treatment.35

Participants varied in how they interpreted their VUS, both within and across studies. For example, some patients viewed their VUS similarly to a positive result,34,35 others viewed their VUS similarly to a negative result,35 and others viewed it as an uncertain and nondefinitive result.33,34,35 Other patients had difficulty making meaning of their VUS.29 Interpretation influenced how participants responded to their VUS, for instance those who viewed the VUS as nondefinitive expressed disappointment to not have an answer.33,34,35 Overall, preparation, context, and interpretation of the VUS emerged as key factors that contributed to variation in psychological responses within and across qualitative studies.

Negative psychological responses to VUS included shock to receive an uncertain result,35 sadness,35 disappointment to not have a clear answer,33,34,35 and regret about having had testing because of the VUS.34,35 Positive psychological responses included relief,33,35 and optimism that their VUS may be better understood in the future.34,35 Some participants had mixed responses to their VUS, reporting both worry about the VUS, and hope that it may be benign.35

Patients with VUS and patients with negative results were similarly likely to have a change in their clinical management

From the meta-analysis, patients with VUS and patients with negative results were similarly likely to have a change in their clinical management after receiving their genetic test results. Across the three studies that were included in the meta-analysis,26,27,32 there was no statistically significant difference in the odds of a change in clinical management for patients with VUS and those with negative results (OR 1.41 [95% CI 0.90 to 2.21], P = 0.182, I2 = 41.33%, Fig. 2e).

Patients with VUS were less likely to have changes in their clinical management than patients with positive results. From the meta-analysis,26,27,32 the odds of a change in clinical management were lower among patients with a VUS than among those with a positive result (OR 0.09 [95% CI 0.05 to 0.19], P < 0.0001, I2 = 84.59%); this difference was statistically significant (Fig. 2f).

Four studies reporting clinical outcomes were not included in the meta-analysis because they did not report the number of patients with VUS who had a change in clinical management,31 they reported behavioral intentions only,28 they did not include comparator groups,22 or they only reported whether VUS had played a role in decision-making but not the number of participants who had a change in management.30 Findings from these studies are reported in Table 3. Among these studies, there were a few instances where clinical actions were taken on the basis of a VUS. In one study, in the context of testing for hereditary cancer, more patients with VUS reported that their genetic test result had played a role in their decision to have extra or more frequent screening than patients with positive and with negative results.30 In another study, among cancer patients who received VUS from testing ordered by nongenetics specialists (e.g., gynecologist), there were four cases of unnecessary surgeries (prophylactic mastectomies and oophorectomies) conducted because patients’ VUS were misunderstood by their clinicians to be deleterious variants.22

Patients’ and health-care providers’ interpretations of the VUS as a health threat or not shaped how they acted on the result

Meta-aggregation of findings from the qualitative studies revealed that patients differed in how they viewed their VUS and what it meant for their clinical diagnosis of the associated condition. For some patients, their VUS changed how they perceived their clinical diagnosis,24,35 while others’ perceptions of their clinical diagnosis were unchanged by their VUS.24 Other patients were uncertain about their clinical diagnosis.35

Patients’ interpretation of their VUS (e.g., as a health threat or not) shaped how they acted on the result. For some patients, interpreting their VUS similarly to a positive result and having a clinical action plan (e.g., monitoring for colon cancer) promoted feelings of empowerment and facilitated coping with the VUS.35 These participants described a fear of missing cancer and thus felt safer interpreting their VUS similarly to a positive result.35 Across clinical contexts, actions taken on the basis of VUS included more frequent visits with health-care providers,33,35 medication changes,33 improved medication adherence,33 making healthier lifestyle choices,33 complying with recommended surveillance,35 placing the VUS in their electronic health record,34 and discussing the VUS with their primary care providers.33,35 In contrast, other patients viewed their VUS more similarly to a negative result, with no associated clinical actions.29,33,35

Health-care providers contributed to shaping how patients interpreted and acted on their VUS. For instance, patients’ interpretations of their VUS echoed what their providers told them about the result,34,35 for example as an uncertain but likely cause of their condition or an uncertain but unlikely cause of their condition.34 In another study, patients reported complying with annual screening recommended by their clinician (though it was not reported whether family history or tumor testing results played a role in the recommended frequency of screening), and one patient reported that their clinician told them they had decided to treat them as a Lynch syndrome patient even though they had a VUS, not a pathogenic variant.35 Finally, patients expected their clinician to play a role in updating them about any changes to the interpretation of their VUS.34,35 Some patients expected their clinician to regularly reassess their VUS and follow up with them over time, even to let them know that nothing had changed about its interpretation.35

Quality appraisal

Quantitative

For most cohort studies, it was unclear whether multiple criteria for critical appraisal were met. Cohort studies (n = 6) were strongest at recruiting participants in each group (positive result, negative result, VUS) from the same population, using appropriate statistical analysis, and identifying confounding factors (Appendix 2). Cross-sectional studies (n = 4) were strongest at clearly defining inclusion criteria, using appropriate statistical analysis, and identifying and dealing with confounding factors (Appendix 2). The case series met 3/9 applicable criteria.

Qualitative

Studies were strongest at maintaining congruity between the research methodology, objectives and data collection strategies, representing participants and their voices, obtaining ethical approval, and congruency between conclusions and analysis (Appendix 2). While some studies located the researcher theoretically, none explicitly described the effect this could have on their interpretation. In addition, no qualitative studies explicitly addressed the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice versa.

DISCUSSION

As multigene panel testing and genomic sequencing are increasingly used in clinical care, patients will increasingly receive VUS. It is important to understand how patients interpret and respond to these uncertain findings to inform practice and policy related to the return of VUS. This systematic review and evidence synthesis comprehensively assessed patients’ psychological and clinical outcomes after receiving a VUS from multigene panel testing or genomic sequencing across clinical contexts. The meta-analyses identified that patients who received VUS from multigene panel testing or genomic sequencing experienced higher genetic test-specific concerns than patients with negative results, experienced similar event-specific distress to patients with negative results, and were not more likely to have a change in their medical management than patients with negative results. Qualitative synthesis revealed multiple factors that contributed to shaping patients’ psychological and clinical outcomes, including the patient’s interpretation of the VUS (e.g., as a health threat or not), and their health-care provider’s interpretation of the VUS and subsequent recommendations.

From the meta-analysis of three studies,25,30,36 the MICRA was able to detect differences in psychological responses between individuals with negative results and VUS, but the IES-R did not. Similarly, individual studies that used the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Cancer Worry Scale (CWS) did not detect differences between groups.23,30 This reflects findings from Robinson et al., who found greater variation in patients’ psychological responses on the scales that measure genetic test–related emotions (MICRA and the Feelings About genomiC Testing Results [FACToR] scale; FACToR was developed from the MICRA for genomic testing for any condition37) than on scales that measure test-independent constructs (e.g., HADS) when evaluating psychological outcomes of receiving secondary findings from genomic sequencing.38 General psychological instruments developed outside of the context of genetic testing (e.g., HADS) may not be sensitive enough to capture differences between patients with different genetic test results, or may be too specific to pick up more subtle emotional impacts of genetic testing. Future research on the psychological outcomes of genetic testing should employ genetic test–specific measures, such as the MICRA or FACToR.

Qualitative synthesis identified that health-care providers played a key role in preparing patients for the possibility of receiving an uncertain result, and in shaping how they interpreted and acted on the VUS. Research in other contexts has also identified the importance of pretest counseling to prepare patients to receive uncertain genetic test results.39 Health-care providers’ own attitudes toward uncertainty may influence when and how they communicate uncertainty to their patients. For instance, genetic counselors have been found to vary in how and when they discuss uncertainty related to multigene panel testing with their patients and have reported that they would prefer consensus about how and when to communicate uncertainty to patients, and less variation in practice.40 It has been argued that health-care providers counseling patients for genetic or genomic testing should explicitly discuss uncertainty and guide their patients to reflect on and appraise uncertainty in their decision-making.41 It may be beneficial to develop practice guidelines for pretest and post-test discussions of VUS, which could contribute to reducing practice variation, and could assist health-care providers in guiding their patients to consider and appraise uncertainty.

While the meta-analysis found no difference in the likelihood of having a change in clinical management between patients with negative results and patients with VUS, studies that were not included in the meta-analysis reported several instances where VUS did play a role in management decisions. For example, one study found that more patients with VUS reported that their genetic test result played a role in their decision to engage in more frequent screening than patients with negative results and patients with positive results.30 This finding may be explained by the fact that the study was conducted among cancer patients; patients with positive results may have undergone risk-reducing surgery instead of opting for increased screening. In addition, one case report identified inappropriate surgeries conducted based on nongenetics health-care providers’ (e.g., gynecologists') misunderstanding of VUS.22 As genetic testing is increasingly ordered by nongenetics specialists, it is important that nongenetics specialists are educated about VUS and how they should be appropriately managed. Practice guidelines or clinical decision support tools may be useful for scenarios where nongenetics specialists order tests or follow up on results, to ensure that VUS are interpreted and managed appropriately.

Patients expected their providers to follow up with them about updates to their VUS; optimism that their result would be better understood in the future helped some patients cope with their VUS. Similarly, other studies have found that patients generally prefer to be recontacted with updates to their genetic results.42,43 Guidelines suggest that it is desirable for patients to learn updates about their genetic test results in both clinical and research settings but differ in the specifics of how recontact should be operationalized.44,45 Differences in recontact practice between clinics and jurisdictions may lead to inequities in information provision and health outcomes.46 A major barrier to recontact is that clinics may be underresourced to routinely follow up with patients about updates to their results. Future research should aim to identify ways to facilitate recontact that are less resource-intensive than current approaches, and to promote consistency in practice with respect to recontact.

This study has several limitations. First, only English-language articles were included in the review, which limits the available evidence. There were few studies available for inclusion in this review, and even fewer included in each meta-analysis. Because of this, fixed-effect meta-analyses were performed, which limits the generalizability of the findings of the meta-analysis to other populations. There was moderate to substantial statistical heterogeneity19 across the studies included in the meta-analyses. Heterogeneity may have been due to various factors including differences in clinical setting, the proportion of affected and unaffected individuals who received testing, family history, other sociodemographic characteristics, or the methodology used in each study. Very few studies were included in the meta-analyses, so sources of heterogeneity could not be explored through meta-regression,19 and statistical heterogeneity could not be taken into consideration in the fixed-effect models. Finally, the quality of the studies included in the systematic review was variable, which limits the strength of the evidence that this systematic review provides.

In conclusion, patients with VUS reported higher genetic test–specific concerns than patients with negative results, but lower genetic test–specific concerns than patients with positive results. Patients with VUS and patients with negative results were equally likely to have a change in their clinical management following return of results, and less likely to have a change in their clinical management than patients with positive results. Health-care providers played an important role in preparing patients to receive uncertain results, and in shaping how they interpreted and responded to their VUS. It may be beneficial to develop pre- and post-test focused practice guidelines or clinical decision support tools related to VUS to promote consistency across providers in pretest counseling and return of results, and to ensure that nongenetics specialists interpret and manage VUS appropriately.

References

Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–424.

Buys S, Sandback J, Gammon A, et al. A study of over 35,000 women with breast cancer tested with a 25-gene panel of hereditary cancer genes. Cancer. 2019;123:1721–1730.

Dixon-Salazar TJ, Silhavy JL, Udpa N, et al. Exome sequencing can improve diagnosis and alter patient management. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:138ra78–138ra78.

Mighton C, Charames G, Wang M, et al. Variant classification changes over time in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Genet Med. 2019;21:2248–2254.

Macklin S, Durand N, Atwal P, Hines S. Observed frequency and challenges of variant reclassification in a hereditary cancer clinic. Genet Med. 2018;20:346–350.

Mersch J, Brown N, Pirzadeh-Miller S, et al. Prevalence of variant reclassification following hereditary cancer genetic testing. JAMA. 2018;320:1266–1274.

Daly MB, Pilarski R, Yurgelun MB, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic, Version 1.2020. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18:380–391.

Culver JO, Brinkerhoff CD, Clague J, et al. Variants of uncertain significance in BRCA testing: evaluation of surgical decisions, risk perception, and cancer distress. Clin Genet. 2013;84:464–472.

O’Neill SC, Rini C, Goldsmith RE, Valdimarsdottir H, Cohen LH, Schwartz MD. Distress among women receiving uninformative BRCA1/2 results: 12-month outcomes. Psychooncology. 2009;18:1088–1096.

Schwartz M, Peshkin B, Hughes C, Main D, Isaacs C, Lerman C. Impact of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation testing on psychologic distress in a clinic-based sample. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:514–520.

Vos J, Otten W, van Asperen C, Jansen A, Menko F, Tibben A. The counsellees’ view of an unclassified variant in BRCA1/2: recall, interpretation, and impact on life. Psychooncology. 2008;17:822–830.

Charrois TL. Systematic reviews: what do you need to know to get started? Can J Hosp Pharm. 2015;68:144–148.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13:179–187.

Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, et al. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (editors). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI, 2020. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global.

Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10:45–53.

Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H Introduction to Meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2009.

Cella D, Hughes C, Peterman A, et al. A brief assessment of concerns associated with genetic testing for cancer: the Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment (MICRA) questionnaire. Health Psychol. 2002;21:564–572.

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane, 2019. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S. Psychometric properties of the Impact of Event Scale–Revised. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:1489–1496.

Munn Z, Dias M, Tufanaru C, et al. Adherence of meta-aggregative systematic reviews to reporting standards and methodological guidance: a methodological review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2019;17:444–450.

Bonadies DC, Brierley KL, Barnett RE, et al. Adverse events in cancer genetic testing: the third case series. Cancer J. 2014;20:246–253.

Bradbury AR, Patrick-Miller LJ, Egleston BL, et al. Patient feedback and early outcome data with a novel tiered-binned model for multiplex breast cancer susceptibility testing. Genet Med. 2016;18:25–33.

Burns C, Yeates L, Spinks C, Semsarian C, Ingles J. Attitudes, knowledge and consequences of uncertain genetic findings in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017;25:809–815.

Esteban I, Vilaro M, Adrover E, et al. Psychological impact of multigene cancer panel testing in patients with a clinical suspicion of hereditary cancer across Spain. Psychooncology. 2018;27:927–34.

Hermel DJ, McKinnon WC, Wood ME, Greenblatt MS. Multi-gene panel testing for hereditary cancer susceptibility in a rural Familial Cancer Program. Fam Cancer. 2017;16:159–166.

Kurian AW, Li Y, Hamilton AS, et al. Gaps in incorporating germline genetic testing into treatment decision-making for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2232–2239.

Lawal TA, Lewis KL, Johnston JJ, et al. Disclosure of cardiac variants of uncertain significance results in an exome cohort. Clin Genet. 2018;93:1022–1029.

Li ST, Sun S, Lie D, et al. Factors influencing the decision to share cancer genetic results among family members: an in-depth interview study of women in an Asian setting. Psychooncology. 2018;27:998–1004.

Lumish HS, Steinfeld H, Koval C, et al. Impact of panel gene testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer on patients. J Genet Couns. 2017;26:1116–1129.

Mauer CB, Pirzadeh-Miller SM, Robinson LD, Euhus DM. The integration of next-generation sequencing panels in the clinical cancer genetics practice: an institutional experience. Genet Med. 2014;16:407–412.

Pederson HJ, Gopalakrishnan D, Noss R, Yanda C, Eng C, Grobmyer SR. Impact of multigene panel testing on surgical decision making in breast cancer patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226:560–565.

Predham S, Hathaway J, Hulait G, Arbour L, Lehman A. Patient recall, interpretation, and perspective of an inconclusive long QT syndrome genetic test result. J Genet Couns. 2017;26:150–158.

Skinner D, Roche MI, Weck KE, et al. “Possibly positive or certainly uncertain?”: participants’ responses to uncertain diagnostic results from exome sequencing. Genet Med. 2018;20:313–319.

Solomon I, Harrington E, Hooker G, et al. Lynch syndrome limbo: patient understanding of variants of uncertain significance. J Genet Couns. 2017;26:866–877.

Wynn J, Holland DT, Duong J, Ahimaz P, Chung WK. Examining the psychosocial impact of genetic testing for cardiomyopathies. J Genet Couns. 2018;27:927–934.

Li M, Bennette CS, Amendola LM, et al. The Feelings About genomiC Testing Results (FACToR) Questionnaire: development and preliminary validation. J Genet Couns. 2019;28:477–490.

Robinson JO, Wynn J, Biesecker B, et al. Psychological outcomes related to exome and genome sequencing result disclosure: a meta-analysis of seven Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research (CSER) Consortium studies. Genet Med. 2019;21:2781–2790.

Semaka A, Balneaves LG, Hayden MR. “Grasping the grey”: patient understanding and interpretation of an intermediate allele predictive test result for Huntington disease. J Genet Couns. 2013;22:200–217.

Medendorp NM, Hillen MA, Murugesu L, Aalfs CM, Stiggelbout AM, Smets EMA. Uncertainty related to multigene panel testing for cancer: a qualitative study on counsellors’ and counselees’ views. J Community Genet. 2019;10:303–312.

Newson AJ, Leonard SJ, Hall A, Gaff CL. Known unknowns: building an ethics of uncertainty into genomic medicine. BMC Med Genomics. 2016;9:57.

Dheensa S, Carrieri D, Kelly S, et al. A ‘joint venture’ model of recontacting in clinical genomics: challenges for responsible implementation. Eur J Med Genet. 2017;60:403–409.

Carrieri D, Dheensa S, Doheny S, et al. Recontacting in clinical practice: the views and expectations of patients in the United Kingdom. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017;25:1106–1112.

Bombard Y, Brothers KB, Fitzgerald-Butt S, et al. The responsibility to recontact research participants after reinterpretation of genetic and genomic research results. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;104:578–595.

David KL, Best RG, Brenman LM, et al. Patient re-contact after revision of genomic test results: points to consider-a statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2019;21:769–771.

Bombard Y, Mighton C. Recontacting clinical genetics patients with reclassified results: equity and policy challenges. Eur J Hum Genet. 2019;27:505–506.

Acknowledgements

We thank Lusine Abrahamyan and Mark Dobrow for their feedback on the research question, PICOS, and first draft of the manuscript. We thank Agnes Sebastian for her assistance retrieving articles to include in full-text review. C.M. received support from the Research Training Centre at St. Michael’s Hospital, a doctoral award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR, GSD-164222) and a studentship funded by the Canadian Centre for Applied Research in Cancer Control (ARCC); ARCC receives core funding from the Canadian Cancer Society (grant 2015–703549). S.S. was supported by a doctoral award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Y.B. was supported by a CIHR New Investigator Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prospero Registration: CRD42018093737

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mighton, C., Shickh, S., Uleryk, E. et al. Clinical and psychological outcomes of receiving a variant of uncertain significance from multigene panel testing or genomic sequencing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Genet Med 23, 22–33 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-020-00957-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-020-00957-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

What is the power of a genomic multidisciplinary team approach? A systematic review of implementation and sustainability

European Journal of Human Genetics (2024)

-

Genetic Evaluation for Monogenic Disorders of Low Bone Mass and Increased Bone Fragility: What Clinicians Need to Know

Current Osteoporosis Reports (2024)

-

Clinical risk management of breast, ovarian, pancreatic, and prostatic cancers for BRCA1/2 variant carriers in Japan

Journal of Human Genetics (2023)

-

Diagnostic yield and clinical relevance of expanded germline genetic testing for nearly 7000 suspected HBOC patients

European Journal of Human Genetics (2023)

-

Combining clinical and molecular characterization of CDH1: a multidisciplinary approach to reclassification of a splicing variant

Familial Cancer (2023)