Abstract

In this study cellulose-rich membranes were fabricated from untreated and treated hardwood biomass solutions in 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate ([Emim][OAc])—dimetylsulfoxide (DMSO) system via wet phase separation. Wood treatment methods aimed to get purified cellulose fraction of wood. Treatment sequence was as followed: deep eutectic solvent pretreatment, sodium chlorite bleaching, and alkaline treatment. Resulted biomass after each treatment step was characterized by chemical composition and crystalline fraction content. Flat-sheet membranes were produced from biomass samples after each treatment step. Characterization of membranes included measurements of pure water permeability and (poly)ethyleneglycol 35 kDa retention, Fourier-transform infrared and Raman spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction measurements and thermogravimetric analysis. The study revealed that it was possible to fabricate membrane from untreated wood as well as from wood biomass after each of treatment steps. The resulted membranes differed in chemical composition and filtration performance. Membrane prepared directly from untreated wood had the highest permeability, the lowest retention; and the most complex chemical composition among others. As treatment steps removed lignin and hemicelluloses from the wood biomass, the corresponding membranes became chemically more homogeneous and showed increased retention and decreased permeability values.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cellulose is considered an abundant renewable resource of great potential for bio-based materials and products. The attractive mechanical properties of this biopolymer enable production of a wide range of cellulose-based materials (Zhang et al. 2017; Khakalo et al. 2019). The presence of many hydroxyl groups, which gives cellulose its remarkably high hydrophilicity, and the extensive network of inter- and intramolecular hydrogen bonds, which provides relatively high chemical and thermal stability, make cellulose an attractive material for filtration membranes (Woodings 2001; Ślusarczyk and Fryczkowska 2019). The network of hydrogen bonds, however, causes difficulties in ensuring effective dissolution of cellulose, which is needed when membranes are produced via phase inversion methods. Solvents capable of cellulose dissolution can be divided into two groups: derivatizing solvents, which interact with hydroxyl groups and form a soluble intermediate that can be isolated later (e.g. conventional viscose and carbamate processes and solvent systems for cellulose such as DMF/N2O4 or DMSO/N2O4, CF3COOH, HCOOH/H2SO4 and Cl2CHCOOH) and non-derivatizing solvents, which do not alter the cellulose chemistry but break hydrogen bonds within the cellulose microfibrils during the dissolution process (e.g. cupro, NMMO·H2O and lithium chloride/N,N-dimethylacetamide (LiCl/DMAc)) (Pinkert et al. 2009; Khakalo et al. 2019). Existing conventional cellulose dissolution and membrane fabrication (both derivatizing and non-derivatizing solvent-based processes) require expensive, hazardous chemicals and cause significant pollution, so there is a need for novel non-derivatizing solvents whose dissolution mechanism maintains the beneficial characteristics of cellulose as a membrane material (Zhang et al. 2017; Khakalo et al. 2019).

One type of novel non-derivatizing solvent, ionic liquids (ILs), is a mixture of solely ions with a melting point often below 100 °C (Parviainen et al. 2014). Due to their remarkably high stability up to 300-400ºC, conductivity and wide liquid range, their use is advantageous in many applications, for example, in electrical devices as lubricants, for biomass pretreatment prior to preparation of composite materials, and for heat transfer (Saha et al. 2019). ILs are considered an attractive medium for the preparation of cellulose and biomass casting solutions due to their high dissolution power and relatively mild dissolution conditions (Raut et al. 2015; Mohd and Draman 2017). The most suitable candidates for large-scale usage are halogen-free, non-corrosive, and reasonably low toxic ILs. An important practical challenge associated with utilization of ILs is their relatively high viscosities, which complicates the dissolution process and results in a need for high temperatures for process facilitation. High temperatures can lead to decomposition of ILs, which is an undesirable side reaction and should be avoided. To prevent decomposition of ILs, a co-solvent, e.g. DMSO, is usually added to the system, enhancing the solvent power of the IL by decreasing the time needed for dissolution even at lower temperatures (Isik et al. 2014). Of the many solvents available, 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate ([Emim][OAc]) is considered an optimal choice as it has relatively low viscosity, high dissolution power for cellulose (up to 20–30 wt.% depending on the temperature of the dissolution) and even higher dissolution power for lignin and hemicelluloses, due to their non-crystalline structure, and it can thus be utilized in dissolution of untreated lignocellulosic materials (Beckwith et al. 2010; Mäki-Arvela et al. 2010; Li et al. 2011; Saha et al. 2017; Mohan et al. 2018).

Preparation of polymeric membranes using ILs as an effective and nonaggressive solvent for cellulose is the subject of intensive study. To cite several examples, Zhu et al. (2014) studied preparation of membranes from cellulose extracted from pineapple leaves with the ionic liquid [Bmim]Cl; Chen et al. (2012) investigated manufacturing of wheat straw regenerated cellulose membranes using the same IL; and Anokhina et al. (2017) researched manufacturing of composite NF membranes from cellulose solutions prepared with a [Emim][OAc]–DMSO mixture. Livazovic et al. (2015) studied preparation of multilayer NF and UF cellulose membranes from solutions made with [Emim][OAc]; Nevstrueva et al. (2018) studied the effect of precipitation temperature on properties of cellulose UF membranes prepared from purified cellulose via immersion precipitation with [Emim][OAc] as a solvent; Tran and Ulbricht (2019) produced UF composite cellulose-cellulose membranes from pure cellulose solutions in [Emim][OAc] and [Bmim][OAc], and studied effects of several parameters, including co-solvent (DMSO) concentration, over the separation performance of manufactured membranes.

[Emim][OAc] has also been implemented for partial surface dissolution as a step in preparation of all-wood composites from delignified birch (Khakalo et al. 2019). However, a thorough literature search yielded that preparation of a membrane directly from wood, which is an abundant source of cellulose, has not been reported. The aim of this study is to investigate whether it is possible to fabricate a cellulose-rich polymeric membrane with UF membrane performance directly from untreated hardwood biomass. The term “cellulose-rich” is used as wood biomass contains lignin, hemicelluloses and extractives, in addition to cellulose, and they are present in the solution used for membrane manufacturing via directly dissolving the wood. The effect of the purification steps used in treatment of the wood biomass on the purity of the recovered cellulose-rich fraction and the properties of the produced membranes is examined to understand the influence of the cellulose purity of the fraction used to produce the cellulose-rich membranes.

A deep eutectic solvent (DES) consisting of choline chloride (ChCl) acting as a hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) and lactic acid (LAc) as a hydrogen bond donor (HBD) was used to recover the cellulose-rich fraction from the wood. ChCl-LAc is attractive as regards wood fractionation and membrane preparation from lignocellulosic biomass as it possesses high and specific dissolution power for lignin and moderate dissolution power for hemicelluloses, leaving cellulose content almost unchanged (Mäki-Arvela et al. 2010; Alvarez-Vasco et al. 2016). In this study, the casting solutions were prepared by dissolving untreated birch, DES-treated birch, DES-treated and bleached birch, and DES-treated, bleached and alkali-extracted birch in a mixture of [Emim][OAc] and DMSO. The membranes were cast onto a non-woven polyester support and coagulated in ultra-pure deionized water. The membranes were tested for permeability and retention performance, and the chemical composition of the membranes and biomass samples was investigated to examine the influence of wood pretreatment on membrane manufacturing.

Experimental

Materials

Debarked birch wood (Betula pendula) chips with a nominal size of 5 × 1 × 0.1 cm were used as a base material for all further operations.

For partial delignification of birch chips through DES treatment, choline chloride (ChCl) (CAS # 67–48-1, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) was used as HBA and lactic acid (LAc) (CAS # 79–33-4, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) as HBD. A mixture of ethanol and deionized water (DI, 15 MΩ, 0.5 – 1 µS/cm) at 9:1 volume ratio was used for filtration and washing of the partially delignified biomass. Subsequent bleaching of DES-treated biomass was done with acetic acid (CAS # 64–19-7, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and sodium chlorite (CAS # 7758–19-2, Acros Organics, Geel, Belgium).

For the two-step alkaline treatment, a NaOH solution was prepared from sodium hydroxide (CAS # 1310–73-2, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) in concentrations of 17.5 and 8.3% for treatment and washing, respectively. Acetic acid (CAS # 64–19-7, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) was used for washing of the treated cellulose.

In analysis of the biomass composition, DI water and 72% sulfuric acid (CAS # 7664–93-9, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) were used in determination of the content of acid soluble and acid insoluble (Klason) lignin. Hydrochloric acid (HCl, CAS # 7647–01-0), anhydrous methanol (CAS # 67–56-1), resorcinol (CAS # 108–46-3, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), pyridine (CAS # 110–86-1, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), trimethylchlorosilane (TMCS, CAS # 75–77-4, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and N,O-bis-trimethylsilyl-trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA, CAS # 25,561–30-2, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) were used in polysaccharide analysis.

A mixture of ionic liquid – 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate, 95% ([Emim][OAc], C1C2ImOAc, CAS # 143,314–17-4, Iolitec Ionic Liquids Technologies GmbH) and DMSO (CAS # 67–68-5, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) was utilized in preparation of the casting solution.

Non-woven polyester was taken from used RO membranes and cleaned mechanically for use as a support material for the membrane preparation. Ultra-pure deionized water was produced by a CENTRA-R 60\120 system (Elga purification system, Veolia Water, UK) and used for washing and as a non-solvent and also in preparation of all solutions.

Polyethylene glycol (PEG, approx. Mw 35 000 g/mol, CAS # 25,322–68-3, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) was used as a model compound for study of membrane retention.

Methods

The pretreatment steps described below are shown schematically in Fig. 1. Untreated birch chips were ground in a ball milling machine and sieved with a No. 120 mesh (nominal sieve opening, 0.125 mm) in order to ease the dissolution process and enable use of analytical methods (e.g. XRD, TG-MS).

DES treatment

For treatment of the birch wood chips, a DES was prepared from ChCl and LAc mixed at a 1:9 mole ratio respectively at 100ºC until a homogeneous transparent mixture was formed. Birch chips and DES were taken at 1:5 mass ratio and placed into an oil bath, where the biomass load was cooked for 18 h at 105 °C. After the treatment was completed, the pulp was vacuum filtered through a filter paper and washed with a mixture of ethanol and DI water at 9:1 volume ratio until the treated pulp released no color. The filtrate was collected and the ethanol removed by evaporation. Recovered lignin was separated from the mixture of recovered DES by addition of water, which led to precipitation of the dissolved lignin. The DES-treated pulp was transferred to an oven and dried at 50 °C for 24 h.

Bleaching

The dried DES-treated pulp was bleached with sodium chlorite and acetic acid according to the “Preparation of Holocellulose” method described by Rowell (2013). At the end of the reaction, when the pulp was almost white-colored, the pulp was filtered and washed with DI water, ethanol and acetone. The pulp was then dried at 50 °C for 24 h.

Two-step alkaline treatment

DES-treated and bleached birch biomass was treated according to the “Preparation of α-cellulose” method by Rowell (2013), which can be described as a two-step alkaline treatment where the first step is treatment with 17.5% NaOH solution and the second step is washing of the treated biomass with 8.3% NaOH solution. The alkali-treated biomass was subsequently washed with DI water, subjected to 10% acetic acid treatment, and washed with DI water again. After the treatment was completed, the resultant pulp was dried at 50 °C for 24 h.

An overview of the analyses of the biomass pulps and membranes produced is presented in Table 1.

Lignin analysis

To estimate the amount of lignin in biomass samples B1–4 and the efficiency of its removal, determination of Klason or acid insoluble lignin (KL, AISL) and acid soluble lignin (ASL) was carried out according to the procedure described in NREL (2012). Acid soluble lignin concentrations were calculated from the obtained UV–Vis absorbance values based on Beer-Lambert’s law with absorptivity of 110 L g−1 cm−1 for 205 nm wavelength.

Analysis of polysaccharides (Acid Methanolysis + GC)

To evaluate changes in hemicellulose content in pulp samples B1–4, analysis was done according to the modified procedure described by Holmbom and Örså (1993). Three parallel samples were measured for all biomass samples. The carbohydrates were analyzed according to Sundberg et al. (1996). The carbohydrate content was analyzed by gas chromatograph HP6890 + injector HP7683 (Agilent, USA). The column was a 25 m/0.20 mm i.d. wide-bore capillary column with a nonpolar phase (HP-1, Agilent Technologies) having a film thickness of 0.11 μm. Carbohydrates were analyzed as monosaccharides; thus, hemicelluloses were transformed to monosaccharides by acid methanolysis before analysis. Calculation of the GC results was done using Relative Response Factors (RRFs), which are described in detail elsewhere (Sundberg et al. 1996; Anugwom et al. 2012; Today 2019).

Membrane preparation

As preparation as a casting solution, the biomass samples exposed to different pretreatments were dissolved in a mixture of [Emim][OAc] and DMSO at a mass ratio of 2:8 respectively. The temperature used depended on the pulp source, i.e. B2 and B3 dissolved at 100ºC, while B1 and B4 dissolved at 120ºC (Fig. 1). Flat sheet polymeric membranes were prepared by Automatic Film Applicator L (BYK-Gardner USA). In membrane casting, a prepared solution with 5 wt.-% concentration of polymer was poured onto a polyester support attached to the membrane casting plate, spread on the flat surface by casting knife with casting thickness of 300 μm and speed 50 mm/s, and immediately after casting transferred into a coagulation bath filled with DI water at 0 °C, where the membrane was preserved for 24 h. All obtained membranes were washed under DI water and then cut into circular coupons with 0.0038 m2 active area for further use. Membranes were stored in water until they were tested in the filtration experiments.

Membrane permeability and retention assessment

For the determination of permeability and separation capabilities of the prepared membranes, small-scale filtration experiments were conducted in an Amicon dead end stirring cell unit (Millipore, USA, Cat No.: XFUF07611, diameter of the stirring device 60 mm), which is presented schematically in Fig. 2.

Prior to determination of the membrane permeability, the membrane was compacted for 1 min at 1 bar, 2 min at 2 bars, 3 min at 3 bars, 4 min at 4 bars and 20 min at 5 bars to minimize errors from compaction of membrane in further measurements and to ensure that the solvents used in the biomass pretreatment and membrane manufacturing were completely rinsed from the membrane pores. The latter was checked by measurement of TOC content in a “leakage” sample (a sample of permeate that was taken while the membrane was compacted at maximum pressure of 5 bar). The permeability of the fabricated membranes was measured at four different pressures (1, 2, 3, and 4 bar) at 25 ± 0.5 °C. The permeability value was calculated with the following Eq. (1):

where P – the permeability of the tested membrane (L/(m2h bar)), J – the mass of pure water permeated through the membrane at 1 min (g/min), A – the area of membrane coupon (m2), τ – the time of collection of the permeate (min), ΔP – the applied pressure (bar).

For the retention study, a solution of model compound PEG 35 kDa was prepared with concentration of 300 ppm and filtered through the membrane at a pressure that was set for each membrane individually in order to have approximately same PEG fluxes around 15 L/(m2 h bar) at 25 °C and 300 rpm stirring speed. Samples of the feed, permeate and retentate were collected from each filtration and their total organic carbon concentration analyzed with a Shimadzu TOC analyzer (TOC-L series, Japan). Retention was calculated based on the concentrations of TOC content in the feed, permeate and retentate samples with the following Eq. (2):

where Cp, Cf and Cr are the total organic carbon concentrations in the permeate, feed and retentate (mg/L) respectively.

Optical spectroscopy analyses

The effect of different pretreatment steps on the chemical composition of membranes M1–4 was evaluated based on Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and Raman spectroscopy. The FTIR analysis was performed with a Frontier MIR/FIR spectrometer (PerkinElmer Inc.) with a universal diamond crystal ATR module in the range 400–4000 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1. Membrane samples were air-dried and separated from the polyester support before analysis. Five points were measured for each membrane sample and measured values averaged. For further analysis, all the spectra were processed with ATR correction, baseline correction and normalization. Raman spectra of air-dried supportless membrane samples were collected using a Kaiser RXN1 spectrometer with 785 nm laser excitation and maximum power of 200 mW. Spectra were collected between 100–3425 cm−1 using a non-contact MR probe.

Thermogravimetric analysis

For thermogravimetric analysis, approx. 10 ± 0.1 mg of the specimen was heated from 25 to 900 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere of 40 mL/min nitrogen at a constant flow rate. Evolved gas emission (EGA) during TGA was analyzed using a mass spectrophotometer (MS 403C Aëolos Mass Spectrophotometer, NETZSCH-Gerätebau GmbH, Selb, Germany) which was coupled with TGA. The analyzed mass range was 10–110 a.m.u. The results were interpreted with N-Proteus® software (NETZSCH-Gerätebau GmbH, Selb, Germany).

X-ray diffraction measurements

To reveal any changes in cellulose crystallinity, pulp B1–4 and membrane samples M1–4 were air-dried, separated from the support, and analyzed with an X-ray diffraction (XRD) device (Bruker AXS D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer). The X-ray diffraction patterns were obtained using Cu Kα (λ = 1.5418 Å) at 40 kV and 40 mA in the range of 2θ = 7 – 60°. To estimate the relative degree of crystallinity of the cellulose, a crystallinity index (CrI) was calculated based on the XRD patterns using the relationship given by Segal et al. (1959) in the following Eq. (3):

where CrI – crystallinity index, Itot – intensity at about 2θ ≈ 22º (represents the crystalline and amorphous material), Iam – intensity at the “valley” between the two main peaks at about 2θ ≈ 18º (represent the amorphous material).

Results and discussion

Chemical composition and crystallinity of the biomass samples after different pretreatment steps

To investigate the effect of different pretreatment steps on the birch biomass, total lignin and carbohydrates content was measured in oven-dried extractive-free samples of B1–4. Cellulose content in the biomass samples was calculated by subtraction of the other constituents. The results are presented in Table 2.

Based on the values presented in Table 2, DES treatment resulted in approximately 65% lignin extraction and approximately 68% and 28% decrease in hemicelluloses and cellulose content respectively. The surprisingly high removal of cellulose might result from thermal degradation of cellulose during the long reaction time at elevated temperatures. (Kumar et al. 2015; Li et al. 2017; Zdanowicz et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2019). It can also be seen from Table 2 that subsequent bleaching decreased total lignin and hemicelluloses content by approximately 94.5% and 83.5% respectively. This drop in the lignin and hemicelluloses content might be explained with the assumption made by Li et al. (2017) that DES treatment promotes partial cleavage of ether bonds between lignin and hemicelluloses, which then promotes further removal of these compounds during the bleaching step. Though relative content of cellulose increased after bleaching, its absolute content decreased slightly (from 35.3 to 32.4 g/100 g of biomass).

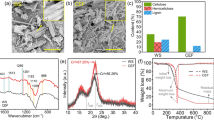

X-ray diffractograms of samples B1–4 are shown in Fig. 3a. It is important to note that the scattered intensity is presented in arbitrary units as the intensity was not normalized to the mass of the samples. Thus, ratios of peak heights rather than absolute intensities were used for comparison between different samples.

The three main peaks in the diffraction pattern are characteristic peaks for cellulose I. The main peak represents a direction perpendicular to the cellulose fiber axis ((200) plane of the Iβ crystal) (Cheng et al. 2011). The position of the peak varies depending on the pretreatment applied: 22.2° for untreated birch (B1), 22.7° for birch subjected to DES treatment (B2), and 22.8° for both bleached DES-treated birch (B3) and alkali-treated bleached DES-treated birch (B4). As this peak is indicative of the distance between the hydrogen-bonded sheets in cellulose I structure, its gradual shift to higher 2θ values shows that the interplanar spacing distance between cellulose sheets is decreasing as a consequence of the pretreatment steps applied. As amorphous lignin and hemicelluloses are removed, as well as part of amorphous cellulose, the remained crystalline regions show more regular and dense molecules arrangement, causing the main diffraction peak shift to higher 2θ values (Beckwith et al. 2010; Gunny, Arbain and Jamal 2017; Neto 2017).

The second characteristic peak at ~ 16° is known to be a composite of the (11¯0) and (110) planes of the Iβ crystal (Cheng et al. 2011; French 2014). It is interesting to note that in samples B1–B3 these two peaks are presented as one composite peak, whereas in the diffractogram of sample B4 the peak shows two separate peaks at 16.7° and 14.9° (Wada, Kondo and Okano 2003; Neto 2017).

The third characteristic peak of cellulose I represents the direction parallel to the fiber axis ((004) plane). This peak is located at ~ 34.5° (Thygesen et al. 2005; Cheng et al. 2011). The peak becomes increasingly distinctive after each pretreatment step applied, which suggests a relative increase in the crystalline phase due to the removal of amorphous compounds such as amorphous cellulose as well as lignin and hemicelluloses.

The CrI values of cellulose I of samples B1-B4 were calculated based on Eq. 3 and equals 54%, 59.9%, 46.4% and 57.8%, respectively, and is consistent with results obtained by Agarwal, Reiner and Ralph (2012). The results are in good accordance with theory as the relative crystalline content increases during DES treatment due to the partial removal of non-cellulosic amorphous compounds (lignin and hemicelluloses) (Beckwith et al. 2010). Although bleaching should have the same effect on sample crystallinity, because it continuously removes the non-cellulosic compounds, the decrease in crystallinity index found in this study might indicate that the bleaching conditions used were a bit too aggressive and led to partial decomposition of cellulose chains. Strong alkaline treatment, as expected, removes mainly amorphous constituents, so relative content of the crystalline part increases again (Dinand et al. 2002; Lionetto et al. 2012).

XRD analysis of membrane samples

To show the type of cellulose present in membrane samples M1–M4, XRD patterns of air-dried membrane samples M1–M4 were measured and are plotted in Fig. 3b. For all samples, the main peak at ~ 22.5° disappeared and a broad asymmetric peak appeared at ~ 20° whose position varied as described above depending on the pretreatment: 20.1° for membrane prepared from untreated birch (M1), 19.2° for membrane prepared from DES-treated birch (M2), 19.8° for membrane prepared from bleached DES-treated birch (M3) and 20.1° for membrane prepared from biomass after the alkaline treatment step (M4). This position is typically assigned to the (110) plane of cellulose II crystals (Isogai et al. 1989; Cheng et al. 2011). Both the broad peak at ~ 16° and the small peak at ~ 34.5°, which are characteristic for cellulose I, disappeared. The absence of these peaks is indicative of disruption of inter-chain hydrogen bonds and elimination of the alignment of the cellulose chains during the dissolution process, respectively (Pang et al. 2014). However, the only clear evidence of cellulose II is the appearance of a distinctive peak for (11¯0) plane at ~ 12.5°, which is present only as a shoulder in the diffractograms of membrane samples M1–M4.

It is reported in literature that during dissolution (or partial dissolution) of cellulose in IL, the inter-chain hydrogen bonds are broken, or the cellulose chains themselves are disrupted (Dinand et al. 2002; Cheng et al. 2011; Neto 2017). The regeneration process occurs upon precipitation in antisolvent, where new inter-sheet hydrogen bonds are established, however, the final regenerated cellulose crystallinity varies (from amorphous to crystalline) depending on the regeneration conditions (Zhu et al. 2006; Ling et al. 2017; Al Hakkaket al. 2019; Taheri, Abdolmaleki and Fashandi 2019). According to the latest findings, the diffractograms of membrane samples M1 – M4 should be recognized as amorphous patterns (Ling et al. 2019; French 2020). Recognition of these patterns as amorphous leads to a conclusion that the composition of dissolved biomass causes less effect on the crystallinity of regenerated cellulose-rich films than the regeneration conditions.

Performance and characteristics of the membranes prepared directly from untreated birch

The permeability and retention values of membranes M1—M4 are presented in Fig. 4. It can be seen that membrane M1 showed the highest permeability (18.9 L/(m2 h bar)) and the lowest retention (24%) compared to the other membranes. As the retention of a membrane is mainly dependent on the properties of its top layer, it might be assumed that the formation of the top layer of membrane M1 prepared from B1 resulted in a loose or uneven structure. As seen in Table 2, the raw wood B1 consists of 21.7% lignin, 27.2% hemicelluloses and 49.3% cellulose. Dissolution of B1 was the most difficult of all the biomass samples and took 170 h at 120 °C. Though some authors, e.g. Miao et al. (2017) and Mohan et al. (2018), state that [Emim][OAc] has high dissolution capacity over non-cellulosic compounds, it should be borne in mind that the studies were done with pure [Emim][OAc] whereas this work used a mixture of [Emim][OAc] and DMSO. Another possible reason for the complicated dissolution is the presence of lignin-carbohydrates complexes (Cheng et al. 2011). Thus, it may be inferred that the milder dissolution parameters used in our study (lower IL concentration, lower temperatures) and the complexity and heterogeneity of the biomass complicates the dissolution of untreated wood in [Emim][OAc]-DMSO and the resulting solution might be unable to form a uniform dense membrane top layer providing better separation performance. Another reason for the formation of an uneven membrane structure might be that the time and temperature (170 h, 120ºC) for dissolution process in this study were sufficient to cause degradation of the cellulose (Kumar et al. 2015; Li et al. 2017; Zdanowicz et al. 2018).

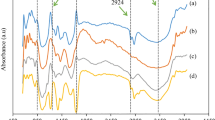

To reveal the chemical composition of the membranes, FTIR spectra of air-dried membranes M1 – M4 were taken and are shown in Fig. 5. It can be seen that clearly visible peaks are located in the fingerprint region (1750 – 1100 cm−1). The assigned wavelengths are given in Table 3. The spectrum for membrane M1 shows peaks at 1592, 1507, 1460, 1325 and 1120 cm−1, which might be related to aromatic skeletal vibrations, CH2- and OCH3- groups, and deformation vibrations of C–H bonds in syringyl rings, and can be considered characteristic peaks of lignin according to Bykov (2008). Consequently, it might be concluded that some amount of lignin has been dissolved and later participated in the formation of the matrix of M1. A peak at 1732 cm−1 is also present and, as reported by Weng et al. (2017), might be related to unconjugated C=O groups in lignin, carboxylic ester hemicellulose structures and some hardwood extractives as they have not been specifically removed (Routa et al. 2017). A small shoulder peak appears at ~ 1250 cm−1, which might result from C–O bonds in xylan and vibrations of syringyl rings in lignin structures (Pandey and Pitman 2003).

To test our hypothesis about the presence of lignin in the membrane matrix of membrane M1, the membrane sample was analyzed using Raman spectroscopy to compare the presence and intensity of the background fluorescence seen in the presence of lignin. The emitted laser induced fluorescence (LIF) caused by lignin is usually regarded as a major drawback of Raman spectroscopy (Lähdetie 2013). However, within the framework of this study, lignin-caused fluorescence emission is useful as an elegant tool for qualitative determination of the presence of lignin in the membrane matrix. The Raman spectrum of the air-dried membrane M1 is given in Fig. 6 together with spectra of other membrane samples. It can be seen that the fluorescence background is the strongest for membrane M1, indicating a greater lignin content in the membrane. Though the spectrum does not give any certain peak due to the strong background fluorescence, a small “wave” can be noticed at 1840 cm−1 which can be assigned to the C=O bond (Lähdetie 2013).

Both FTIR and Raman spectroscopy support the conclusion that lignin was present in the membrane matrix of M1. However, the absence of characteristic peaks in FTIR and strong fluorescence in the Raman spectra mean that the presence of hemicelluloses remains unclear. To ascertain the presence of hemicelluloses and study thermal degradation of the membranes, TG-MS analysis was performed on the freeze-dried support-free membrane samples. The TG and DTG curves of samples M1–4 are presented in Figs. 7 and 8 respectively. It can be seen from Fig. 7 that the studied membranes decomposed over a large temperature range following the four-stage pyrolysis process described for lignocellulosic biomass by Sanchez-Silva et al. (2012). The moisture evolution and loss of volatiles happened at approximately 75—120 °C. Biomass decomposition slowly started at approx. 170 °C, indicating the presence of hemicelluloses in the membrane matrix of M1, as both lignin and cellulose decomposition start at higher temperatures (above 310 °C) (Sanchez-Silva et al. 2012; López-González et al. 2013).

It can be seen in Fig. 8 that the DTG curve of membrane M1 has a broad shoulder at 230–295 °C, which is a clear evidence of hemicelluloses presence, and the main peak shifts to 350 °C, which also points to the presence of lignin structures with higher thermal stability than those of hemicelluloses and cellulose.

As wood biomass consists mainly of different polymeric compounds, its thermal degradation is a complex process that produces a wide range of low-molecular weight compounds (Lv and Wu 2012). MS fragments that have relatively high intensity were selected from pyrolysis of sample M1 and their evolution profiles with pyrolysis temperature were plotted and are shown in Online Resource Figs. S1 – 3. The release of major compounds from membrane M1 has broad peaks due to the presence of components with different thermal stability whose decomposition starts and finishes at different temperatures. The important releasing profile of m/z 109 (guaiacol) is present in Fig. S3. This MS curve was the only characteristic curve for the evolution of products of lignin pyrolysis and its presence in sample M1 is in agreement with results from FTIR and Raman spectroscopy, confirming the presence of lignin in the membrane matrix (Brebuet al. 2013).

Performance and chemical content of the membranes prepared from DES-treated birch

Membrane M2 was prepared from B2 following the same procedure as described above. Dissolution of the DES-treated birch biomass (B2) was much easier than that of the raw wood (B1) and took approximately 20 h at 100 °C. Permeability and retention values measured with this membrane are shown in Fig. 4. Membrane M2 shows lower permeability than M1 (10.5 to 18.9 L/(m2 h bar)) and significantly higher retention of PEG 35 kDa (67.3 to 24%). From Table 2, it can be seen that the DES treatment removed approximately 65% of lignin and 68% of hemicelluloses, which might ease the dissolution of the pulp and promote the formation of a homogeneous solution, which thus resulted in a more uniform and denser top layer giving better retention values.

FTIR, Raman spectroscopy and TG-MS analyses were performed to compare the chemical composition of membranes M2 and M1, and the results are presented in Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8, and S1-3 respectively. In Fig. 5, the FTIR spectrum of M2 is significantly different from that of M1, where no characteristic peaks for lignin are found. The peak at 1732 cm−1 has slightly lower intensity and, as discussed above, cannot be exclusively attributed to lignin, hemicelluloses or extractives. The peak at 1200 cm−1 might result from C–O stretching vibrations formed from xylan degradation (Pandey and Pitman 2003), which is in good agreement with results in Table 2 and shows that the decrease in hemicelluloses content might result from degradation of xylan during the DES treatment or more complete dissolution of xylan due to its initially lower content in sample B2. The absence of characteristic peaks and quite low penetration of FTIR spectra (approx. 10 μm) means that it cannot be guaranteed that no lignin was present in membrane M2.

It can be seen from Fig. 6 that the Raman spectrum of membrane M2 shows significantly lower background fluorescence than M1, suggesting that some amount of lignin might still be present in the matrix of M2, but lignin content is lower than in sample M1. Though the spectrum does not exhibit any certain peak, due to strong background fluorescence, a peak can nevertheless be seen at 1840 cm−1 that might be assigned to the C=O bond (Lähdetie 2013).

Figures 7 and 8 give TG and DTG curves for membrane M2. The degradation curves follow the same pattern as those of M1, decomposing across a large temperature range with humidity elimination below 120 °C and aromatic condensation above 400 °C, resulting in slow loss of mass at high temperatures. In Fig. 7, however, it can be seen that the slope of the curve becomes sharper, indicating a more homogeneous chemical composition for M2 than M1. In Fig. 8, the shoulder at 240–305 °C becomes smaller, indicating that the hemicelluloses (which have lower degradation temperature) are still present but their content has decreased.

The profiles of the main degradation products in Figs. S1-3 mostly follow the same trend: peaks become sharper and narrower, and they shift to higher temperatures, indicating, as discussed above, that the composition of membrane M2 became more uniform as lignin and hemicelluloses are partially removed. It is important to note that the guaiacol releasing profile (m/z 109) is still present for membrane M2, demonstrating that some amount of lignin remained in the membrane matrix even though its initial concentration in the pulp of B2 was significantly lower than in pulp B1.

Performance and chemical composition of the membranes prepared from bleached DES treated birch

Membrane M3 from bleached DES-treated birch biomass (B3) was prepared the same way as membrane M2. Dissolution was done at the same temperature and took shorter time (12 h). Permeability and retention values measured with this membrane are shown in Fig. 4. It can be seen that although the lignin and hemicelluloses content of the biomass is noticeably lower than that of B2, no significant changes were observed for permeability (9.4 to 10.5 L/(m2 h bar)) nor retention (70.2 to 67.3%). The result might suggest that lignin and hemicelluloses content have an impact on membrane permeability and retention only above a certain threshold concentration, but this hypothesis needs further investigation.

In Fig. 5, the same FTIR peaks are found in the spectrum of membrane M3 as membrane M2. However, the Raman spectrum of M3, presented in Fig. 6, is clearly different from the spectra of membrane M1 and M2. Comparing the intensities of background fluorescence, it can be seen that intensity decreases in the following order: M1 > M2 > M3, indicating a decrease in lignin content in the membrane matrix. The peak at 1840 cm−1 is still present in the spectrum of membrane M3, which might be interpreted as a sign of the presence of hemicelluloses as there is no peak at this wavenumber in the spectrum of membrane M4 (Lähdetie 2013). Furthermore, the presence of hemicelluloses is in agreement with the results presented in Table 2.

The TG and DTG curves of M3 can be seen in Figs. 7, 8. The M3 degradation curves follow the same pattern as those for membranes M1 and M2, decomposing in a large temperature range with humidity elimination below 120 °C and aromatic condensation above 400 °C, followed by slow loss of mass at high temperatures. However, the curve slope in Fig. 7 is sharper, indicating even more homogeneous chemical composition in M3 than M1 and M2. The TG curve of membrane M3 shows that it has three times higher residue than the other samples. A possible explanation might be traces of the bleaching chemical (i.e. sodium chlorite) in the biomass. Inorganic salts are well-known to cause increased char formation (due to increase in the dielectric constant of the carbohydrates melt in the presence of salt). It is also possible that salt catalyzed a branch of the reaction network that forms more char (Varhegyi et al. 1988).

The shoulder at 240–305 °C in Fig. 8 is smaller than for M1 and M2, showing that the hemicelluloses (which have lower degradation temperature) content has decreased. Interestingly, M3 has lower DTGmax (10 vs 15%/min) than M2, which can also be attributed to char formation reactions due to the presence of alkaline ions.

The same trend can be seen in the releasing profiles of the main degradation products in Figs. S1-3, i.e. peaks become sharper and narrower, and they shift to higher temperatures, indicating, as discussed above, that the composition of membrane M3 became more uniform as lignin and hemicelluloses content continued to decrease. Another important result is that the guaiacol releasing profile (m/z 109) disappeared, showing that no lignin remained in the membrane matrix, even though a small amount was present in B3 (Table 2). It might be concluded that acid soluble lignin (as the only fraction present in the composition of biomass B3) tends to be removed from the membrane matrix during precipitation in a coagulation bath.

Performance and chemical composition of the membranes prepared from DES-treated, bleached alkali-extracted birch

Clear trends can be observed in the permeability and retention results presented in Fig. 4. The pure water permeability of the membranes decreases with each pretreatment step, showing the highest value for membrane M1 (18.9 L/(m2h bar)) and the lowest for membranes M3 (9.4 L/(m2h bar)) and M4 (9.5 L/(m2h bar)). Conversely, the retention of PEG 35 kDa increased with each pretreatment step applied, showing the lowest value for membrane M1 (24%) and the highest for membrane M4 (86%). The permeabilities of membranes M2–4 are in the same range and differ from that of membrane M1.

Membrane M4 prepared from alkali-treated bleached DES-treated birch biomass (B4) was prepared in the same way as membrane M1: the dissolution was done at the same temperature (120 °C) but took longer (120 h) than preparation of casting solutions from biomass B2 and B3. The longer time and higher temperatures of B4 dissolution might be explained with reference to the chemical composition of the biomass, which becomes more homogeneous with each pretreatment step applied. The overall decrease in lignin and hemicelluloses content after the final pretreatment step equals 98% and 92% respectively. The relative content of cellulose in biomass sample B4 is 89.2% (Table 2). The presence of hemicelluloses in the biomass has been reported to ease the dissolution process, due to the release of acetic acid from the acetyl units of hemicelluloses, which increases the overall polarity and thus promotes further dissolution (Triantafyllidis et al. 2013). Thus, it might be the case that removal of hemicelluloses after some point hampers the dissolution process as acetyl units no longer contribute to the polarity.

From another point of view, it seems that even small concentrations of hemicelluloses can affect the formation of the top layer, since, as can be seen in Table 2, there is no large difference in hemicelluloses content between biomass B3 (10.8%) and B4 (6.3%) but the retention values of membranes M3 and M4 are significantly different (70.2 vs 86.1%). Moreover, it has been suggested that lignin can act like a pore-former agent due to the accelerated diffusional rate between solvent and non-solvent caused by the presence of lignin in the casting solution, which might also contribute to the formation of a looser membrane structure when lignin is present in the biomass (Vilakati et al. 2015; Esmaeili et al. 2018). The FTIR spectrum of M4, shown in Fig. 5, differs from that of the others as it does not have a peak at 1732 cm−1, which might mean that there are no hemicelluloses, lignin or extractives in the membrane matrix. From Fig. 6, it can be seen that the Raman spectrum of membrane M4 has common features with spectra presented elsewhere (Beckers 2015; Lähdetie 2013), showing peaks at 900, 1100, 1370 and 2900 cm−1, which might be attributed to amorphous cellulose, C–C and C–O stretch, HCC, HCO and HOC bending and C–H stretch sp3 respectively.

Membrane M4 has the highest degradation rate (DTGmax 24%/min) and the steepest slope on the TG graph (Figs. 7 and 8), showing that the chemical composition is as homogeneous as possible and membrane M4 consists mainly of cellulose. The absence of a shoulder and only one main peak in Fig. 8 indicates that no hemicelluloses remained in the membrane matrix of M4. The evolution of the main m/z signals in Figs. S1-3 confirms the trend discussed above that as the composition of the pulps becomes more homogeneous, so too does the composition of the derived membrane. Broad mass peaks become narrower as they no longer derive from different sources but only from cellulose, which exhibits a sharp devolatilization process (Lv and Wu 2012).

Conclusions

Fabrication of polymeric cellulose-rich membranes from hardwood (birch) biomass subjected to different pretreatments and dissolved in a mixture of [Emim][OAc]-DMSO via phase inversion method was performed. Characterization of the membranes was done by measuring pure water permeability and PEG retention, and carrying out ATR-FTIR, Raman spectroscopy, XRD and TG-MS measurements. Wood biomass was subjected to sequential pretreatment steps: partial removal of lignin and carbohydrates during DES extraction (ChCl-Lac, 1:9 mol ratio), NaClO2 bleaching, and two-step (17.5 and 8.3%) alkaline treatment, described in literature for the preparation of α-cellulose. The resultant chemical composition was characterized by XRD, total lignin, hemicelluloses and cellulose content.

The results showed that it is possible to fabricate a membrane from each type of the utilized biomass, even by dissolving milled hardwood directly without any pretreatment. However, the biomass pretreatments significantly affected the dissolution of biomass in the mixture of [Emim][OAc]-DMSO and the properties of the prepared membranes.

Chemical characterization of the prepared membranes showed that all membranes but one had complex chemical composition. The exception was the membrane prepared from biomass after alkaline extraction, which consisted of pure cellulose. This difference in chemical composition was clearly observed in thermogravimetric analysis, FTIR and Raman spectroscopy analysis. Measurement of background fluorescence in Raman spectroscopy showed that there was lignin in the membrane matrix of the first two membranes. Hemicelluloses were present in all the membranes bar the membrane prepared from biomass, which was also alkali-extracted. As lignin and hemicelluloses were present in all biomass samples and were found in some but not all membranes, two findings should be noted. First, the [Emim][OAc]-DMSO mixture is capable of dissolving some amount of lignin and hemicelluloses, and second, below a certain concentration these compounds do not remain in the membrane matrix and may be removed during either precipitation or washing of the membrane. The membrane fabricated from untreated birch showed the highest permeability and the lowest retention. This result might be attributed to the complexity and recalcitrance of the chemical composition of the untreated wood, which makes the dissolution harder and prevents formation of dense top-layer, as well as to the pore-forming properties of lignin and overall complexity of the membrane formed. The retention of cellulose-rich membrane was found to depend on the purity of cellulose in its matrix, because with each pretreatment step applied to the biomass, the resulting membrane became chemically more homogenous, tighter, and showed better retention. The results also demonstrated that although it is possible to prepare ultrafiltration type membranes directly from wood, the novel pretreatments prior to dissolution applied in this study lead to better membrane properties.

References

Agarwal U, Reiner R, Ralph S (2012) Estimation of cellulose crystallinity of lignocelluloses using near-IR FT-Raman spectroscopy and comparison of the raman and segal-WAXS methods. J Agric Food Chem 61(1):103–113. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf304465k

Al Hakkak J, Grigsby W, Kathirgamanathan K, Edmonds N (2019) Generation of spherical cellulose nanoparticles from ionic liquid processing via novel nonsolvent addition and drying. Adv Mater Sci Eng. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/2081027

Alvarez-Vasco C, Ma R, Quintero M, Guo M, Geleynse S, Ramasamy K, Wolcott M, Zhang X (2016) Unique low-molecular-weight lignin with high purity extracted from wood by deep eutectic solvents (DES): a source of lignin for valorization. Green Chem 18(19):5133–5141. https://doi.org/10.1039/c6gc01007e

Anokhina T, Pleshivtseva T, Ignatenko V, Antonov S, Volkov A (2017) Fabrication of composite nanofiltration membranes from cellulose solutions in an [Emim]OAc–DMSO mixture. Pet Chem 57(6):477–482. https://doi.org/10.1134/S096554411706002

Anugwom I, Mäki-Arvela P, Virtanen P, Willför S, Sjöholm R, Mikkola J (2012) Selective extraction of hemicelluloses from spruce using switchable ionic liquids. Carbohydr Polym 87(3):2005–2011.

Beckers M (2015) Analysing lignin and wheat straw pre-treated by novel solvents. Master thesis. Eindhoven University of Technology.

Beckwith SW, Albers RG, Hubert P (2010) SAMPE 2010 - New materials and processes for a new economy, Seattle WA, May 17–20, 2010 - 66.3.2 Crystal Structure. Society for the Advancement of Material and Process Engineering (SAMPE)

Brebu M, Tamminen T, Spiridon I (2013) Thermal degradation of various lignins by TG-MS/FTIR and Py-GC-MS. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 104:531–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2013.05.016

Bykov I (2008) Characterization of natural and technical lignins using FTIR spectroscopy. Master thesis. Luleå University of Technology.

Chen H, Wang N, Liu L (2012) Regenerated cellulose membrane prepared with ionic liquid 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride as solvent using wheat straw. J Chem Technol Biotechnol 87(12):1634–1640. https://doi.org/10.1002/jctb.3802

Cheng G, Varanasi P, Li C, Liu H, Melnichenko Y, Simmons B, Kent M, Singh S (2011) Transition of cellulose crystalline structure and surface morphology of biomass as a function of ionic liquid pretreatment and its relation to enzymatic hydrolysis. Biomacromol 12(4):933–941. https://doi.org/10.1021/bm101240z

Dinand E, Vignon M, Chanzy H and Heux L (2002) Mercerization of primary wall cellulose and its implication for the conversion of cellulose I→cellulose II. Cellulose, 9, 7–18. doi.org:10.1023/A:1015877021688

Esmaeili M, Anugwom I, Mänttäri M, Kallioinen M (2018) Utilization of DES-lignin as a bio-based hydrophilicity promoter in the fabrication of antioxidant polyethersulfone membranes. Membranes 8(3):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes8030080

French AD (2014) Idealized powder diffraction patterns for cellulose polymorphs. Cellulose 21:885–896. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-013-0030-4

French AD (2020) Increment in evolution of cellulose crystallinity analysis. Cellulose 27:5445–5448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-020-03172-z

Gunny A, Arbain D, Jamal P (2017) Effect of structural changes of lignocelluloses material upon pre-treatment using green solvents. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4981844

Holmbom B, and Örså F (1993) Methods for analysis of dissolved and colloidal wood components in papermaking process waters and effluents. In: Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium, Wood Pulping Chem. Beijing, vol 2, pp 810–817

Isik M, Sardon H, Mecerreyes D (2014) Ionic liquids and cellulose: dissolution, chemical modification and preparation of new cellulosic materials. Int J Mol Sci 15(7):11922–11940. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms150711922

Isogai A, Usuda M, Kato T, Uryu T, Atalla R (1989) Solid-state CP/MAS carbon-13 NMR study of cellulose polymorphs. Macromolecules 22(7):3168–3172. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma00197a045

Khakalo A, Tanaka A, Korpela A, Hauru L, Orelma H (2019) All-wood composite material by partial fiber surface dissolution with an ionic liquid. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 7(3):3195–3202. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b05059

Kumar A, Parikh B, Pravakar M (2015) Natural deep eutectic solvent mediated pretreatment of rice straw: bioanalytical characterization of lignin extract and enzymatic hydrolysis of pretreated biomass residue. Environ Sci Pollut Res 23(10):9265–9275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-015-4780-4

Lähdetie A (2013) Wood biomass characterization by Raman spectroscopy. Doctoral dissertation. Aalto University.

Li T, Lyu G, Liu Y, Lou R, Lucia L, Yang G, Chen J, Saeed H (2017) Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) for the isolation of willow lignin (Salix matsudana cv Zhuliu). Int J Mol Sci 18(11):22–66. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18112266

Li X, Zhu L, Zhu B, Xu Y (2011) High-flux and anti-fouling cellulose nanofiltration membranes prepared via phase inversion with ionic liquid as solvent. Sep Purif Technol 83:66–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2011.09.012

Ling Z, Chen S, Zhang X, Takabe K, Xu F (2017) Unraveling variations of crystalline cellulose induced by ionic liquid and their effects on enzymatic hydrolysis. Sci Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09885-9

Ling Z, Wang T, Makarem M, Santiago Cintrón M, Cheng HN, Kang X, Bacher M, Potthast A, Rosenau T, King H, Delhom CD, Nam S, Edwards JV, Kim SH, Xu F, French AD (2019) Effects of ball milling on the structure of cotton cellulose. Cellulose 21:885–896. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-018-02230-x

Lionetto F, Del Sole R, Cannoletta D, Vasapollo G, Maffezzoli A (2012) Monitoring wood degradation during weathering by cellulose crystallinity. Materials 5(10):1910–1922. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma5101910

Liu Q, Yuan T, Fu Q, Bai Y, Peng F, Yao C (2019) Choline chloride-lactic acid deep eutectic solvent for delignification and nanocellulose production of moso bamboo. Cellulose 26(18):9447–9462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-019-02726-0

Livazovic S, Li Z, Behzad A, Peinemann K, Nunes S (2015) Cellulose multilayer membranes manufacture with ionic liquid. J Membr Sci 490:282–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2015.05.009

López-González D, Fernandez-Lopez M, Valverde J, Sanchez-Silva L (2013) Thermogravimetric-mass spectrometric analysis on combustion of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresour Technol 143:562–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2013.06.052

Lv G, Wu S (2012) Analytical pyrolysis studies of corn stalk and its three main components by TG-MS and Py-GC/MS. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 97:11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2012.04.010

Mäki-Arvela P, Anugwom I, Virtanen P, Sjöholm R, Mikkola J (2010) Dissolution of lignocellulosic materials and its constituents using ionic liquids—A review. Ind Crops Prod 32(3):175–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2010.04.005

Miao J, Yu Y, Jiang Z, Tang L, Zhang L (2017) Partial delignification of wood and membrane preparation using a quaternary ammonium ionic liquid. Sci Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42472

Mohan M, Deshavath N, Banerjee T, Goud V, Dasu V (2018) Ionic liquid and sulfuric acid-based pretreatment of bamboo: biomass delignification and enzymatic hydrolysis for the production of reducing sugars. Ind Eng Chem Res 57(31):10105–10117. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.8b00914

Mohd N, Draman S, SallehYusof MN (2017) Dissolution of cellulose in ionic liquid: a review. AIP Conf Proc 1809:020035. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4975450

National Renewable Energy Laboratory, NREL (2012) Determination of structural carbohydrates and lignin in biomass. TP-510–42618.

Neto W (2017) Morphological investigation of cellulose nanocrystals and nanocomposite applications. Ph.D. Université Grenoble Alpes; Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, 2.

Nevstrueva D, Pihlajamäki A, Nikkola J, Mänttäri M (2018) Effect of precipitation temperature on the properties of cellulose ultrafiltration membranes prepared via immersion precipitation with ionic liquid as solvent. Membranes 8(4):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes8040087

Pandey K, Pitman A (2003) FTIR studies of the changes in wood chemistry following decay by brown-rot and white-rot fungi. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation 52(3):151–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0964-8305(03)00052-0

Pang J, Liu X, Wu M, Wu Y, Zhang X, Sun R (2014) Fabrication and characterization of regenerated cellulose films using different ionic liquids. J Spectrosc (Hindawi) 2014:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/214057

Parviainen H, Parviainen A, Virtanen T, Kilpeläinen I, Ahvenainen P, Serimaa R, Grönqvist S, Maloney T, Maunu S (2014) Dissolution enthalpies of cellulose in ionic liquids. Carbohydr Polym 113:67–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.07.001

Pinkert A, Marsh K, Pang S, Staiger M (2009) Ionic liquids and their interaction with cellulose. Chem Rev 109(12):6712–6728. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr9001947

Raut D, Sundman O, Su W, Virtanen P, Sugano Y, Kordas K, Mikkola J (2015) A morpholinium ionic liquid for cellulose dissolution. Carbohydr Polym 130:18–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.04.032

Routa J, Brännström H, Anttila P, Mäkinen M, Jänis J and Asikainen A (2017) Wood extractives of Finnish pine, spruce and birch – availability and optimal sources of compounds : A literature review. Natural resources and bioeconomy studies 73/2017. Natural Resources Institute Finland, Helsinki. 55 p.

Rowell R (2013) Handbook of wood chemistry and wood composites. Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton

Saha K, Dasgupta J, Chakraborty S, Antunes FAF, Sikder J, Curcio S, Santos JC, Arafat HA, Silva SS (2017) Optimization of lignin recovery from sugarcane bagasse using ionic liquid aided pretreatment. Cellulose 24:3191–3207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-017-1330-x

Saha K, Verma P, Sikder J, Chakraborty S, Curcio S (2019) Synthesis of chitosan-cellulase nanohybrid and immobilization on alginate beads for hydrolysis of ionic liquid pretreated sugarcane bagasse. Renew Energ 133:66–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2018.10.014

Sanchez-Silva L, López-González D, Villaseñor J, Sánchez P, Valverde J (2012) Thermogravimetric–mass spectrometric analysis of lignocellulosic and marine biomass pyrolysis. Bioresour Technol 109:163–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2012.01.001

Segal L, Creely J, Martin A, Conrad C (1959) An empirical method for estimating the degree of crystallinity of native cellulose using the X-Ray diffractometer. Text Res J 29(10):786–794. https://doi.org/10.1177/004051755902901003

Ślusarczyk C, Fryczkowska B (2019) Structure-property relationships of pure cellulose and GO/CEL membranes regenerated from ionic liquid solutions. Polymers 11(7):1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11071178

Sundberg A, Sundberg K, Lillandt C, Holmbom B (1996) Determination of hemicelluloses and pectins in wood and pulp fibers by acid methanolysis and gas chromatography. Nord Pulp Pap Res J 4:216–226. https://doi.org/10.3183/NPPRJ-1996-11-04-p216-219

Taheri N, Abdolmaleki A, Fashandi H (2019) Impact of non-solvent on regeneration of cellulose dissolved in 1-(carboxymethyl)pyridinium chloride ionic liquid. Polym Int 68(12):1945–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pi.5903

Thygesen A, Oddershede J, Lilholt H, Thomsen AB, Ståhl K (2005) On the determination of crystallinity and cellulose content in plant fibres. Cellulose 12:563. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-005-9001-8

Today C (2019) What is a response factor? Chromatography today. https://www.chromatographytoday.com/news/gc-mdgc/32/breaking-news/what-is-a-response-factor/31169. Accessed 10 Jun. 2019

Tran D, Ulbricht M (2019) Herstellung von Ultrafiltrations-Membranen aus Lösungen von Cellulose in ionischen Flüssigkeiten. Chem Ing Tech 91(8):1123–1128. https://doi.org/10.1002/cite.201900044

Triantafyllidis KS, Lappas AA, Stöcker M (2013) Role of catalysis for the sustainable production of bio-fuels and bio-chemicals - 7.8 ionic liquids. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Varhegyi G, Antal M, Szekely T, Till F, Jakab E (1988) Simultaneous thermogravimetric-mass spectrometric studies of the thermal decomposition of biopolymers. 1. Avicel cellulose in the presence and absence of catalysts. Energy Fuels 2(3):267–272. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef00009a007

Vilakati GD, Hoek E, Mamba BB (2015) Investigating the usability of alkali lignin as an additive in polysulfone ultrafiltration membranes. BioResources 10:3079–3096. https://doi.org/10.15376/biores.10.2.3056-3069

Wada M, Kondo T, Okano T (2003) Thermally induced crystal transformation from cellulose Iα to Iβ. Polym J 35(2):155–159. https://doi.org/10.1295/polymj.35.155

Weng R, Chen L, Xiao H, Huang F, Lin S, Cao S, Huang L (2017) Preparation and characterization of cellulose nanofiltration membrane through hydrolysis followed by carboxymethylation. Fibers Polym 18(7):1235–1242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12221-017-7200-1

Woodings C (2001) Regenerated cellulose fibres - 5.4 Products and Application. Woodhead Publishing, Amsterdam

Zdanowicz M, Wilpiszewska K, Spychaj T (2018) Deep eutectic solvents for polysaccharides processing A review. Carbohydr Polym 200:361–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.07.078

Zhang J, Wu J, Yu J, Zhang X, He J, Zhang J (2017) Application of ionic liquids for dissolving cellulose and fabricating cellulose-based materials: state of the art and future trends. Mater Chem Front 1(7):1273–1290. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6QM00348F

Zhu S, Wu Y, Chen Q, Yu Z, Wang C, Jin S, Ding Y, Wu G (2006) Dissolution of cellulose with ionic liquids and its application: a mini-review. Green Chem 8(4):325. https://doi.org/10.1039/b601395c

Zhu X, Wang Y, Wei X, Li J, Wang F (2014) Preparation of pineapple leaf cellulose membrane. Adv Mat Res 1046:13–17. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.1046.13

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank laboratory technician Toni Väkiparta for help with the XRD measurements. Financial support from the EkspSäätiö Foundation is gratefully acknowledged.

Funding

Open access funding provided by LUT University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: all authors; Methodology: all authors; Formal analysis and investigation: A.L., I.A., M.E., T.V., L.P.; Writing—original draft preparation: A.L.; Writing–review and editing: all authors; Funding acquisition: M.K., M.M.; Resources: M.K., M.M.; Supervision: M.K., M.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lopatina, A., Anugwom, I., Esmaeili, M. et al. Preparation of cellulose-rich membranes from wood: effect of wood pretreatment process on membrane performance. Cellulose 27, 9505–9523 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-020-03430-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-020-03430-0