Abstract

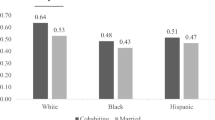

Interracial couples cohabit at higher rates than same-race couples, which is attributed to lower barriers to interracial cohabitation relative to intermarriage. This begs the question of whether the significance of cohabitation differs between interracial and same-race couples. Using data from the 2006–2017 National Survey of Family Growth, we assessed the meaning of interracial cohabitation by comparing the pregnancy risk, pregnancy intentions, and union transitions following a pregnancy among women in interracial and same-race cohabitations. The pregnancy and union transition behaviors of women in White-Black cohabitations resembled those of Black women in same-race cohabitations, suggesting that White-Black cohabitation serves as a substitute to marriage and reflecting barriers to the formation of White-Black intermarriages. The behaviors of women in White-Hispanic cohabitations fell between those of their same-race counterparts or resembled those of White women in same-race cohabitations. These findings suggest that White-Hispanic cohabitations take on a meaning between trial marriage and substitute to marriage and support views that Hispanics with White partners are a more assimilated group than Hispanics in same-race unions. Results for pregnancy intentions deviated from these patterns. Women in White-Black cohabitations were less likely than Black women in same-race cohabitations to have an unintended pregnancy, suggesting that White-Black cohabitations are considered marriage-like unions involving children. Women in White-Hispanic cohabitations were more likely than White and Hispanic women in same-race cohabitations to have an unintended pregnancy, reflecting possible concerns about social discrimination. These findings indicate heterogeneity in the significance of interracial cohabitation and continuing obstacles to interracial unions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

All data sets from the National Survey of Family Growth used for this analysis are publicly available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/index.htm.

Notes

These rules are typically used to explain the outcomes and ethnoracial identification of mixed-race individuals (Campbell 2009). Some studies, however, have tested the validity of these rules for the cultural orientation of interracial couples (Vasquez 2014). Because attitudes toward intermarriages differ by race/ethnicity, some interracial couples have more contact with their non-White kin, whereas others have more contact with their White kin. Prolonged exposure and greater emotional proximity to non-White kin may lead some interracial couples to identify more closely with the cultural values of their non-White family members. If this is the case, their fertility will mirror that of same-race couples in the non-White group. The opposite will be true for interracial couples who have more contact with White kin.

Unlike prior waves, the public-use files of the 2015–2017 NSFG do not report the months of cohabitation, birth, or marriage.

Results are presented in the online appendix (Table A4).

We conducted two supplementary analyses. The first used a measure of couples’ joint race/ethnicity that cross-classified male and female partners’ race/ethnicity (online appendix, Table A5). We also ran models that controlled for the gender of the minority partner in the interracial union (available upon request). Our results were robust.

Our models include pregnancies conceived between 1977 and 2017. Because fertility disparities by couples’ joint race/ethnicity may have changed over time, we ran supplementary models including the year of pregnancy. Our results (available upon request) were robust.

NSFG reports only the current partner’s education. We could not control for male partner’s education.

We tried to control for parity in the relationship (0, 1, 2+), but the models for risk of pregnancy failed to converge because of its unusually high correlation with union duration. Inclusion of this variable did not alter the results for pregnancy intentions or union transitions.

These results are described in greater detail in the online appendix (Table A6).

We attempted to adjust for clustering using the sampling stratum (SEST), cluster (SECU), and individual (CASEID), but our models would not converge.

NSFG does not collect school enrollment histories or measure job demandingness.

References

Bratter, J. L., & Eschbach, K. (2006). “What about the couple?” Interracial marriage and psychological distress. Social Science Research, 35, 1025–1047.

Brown, S. L., Stykes, J. B., & Manning, W. D. (2016). Trends in children’s family instability, 1995–2010. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78, 1173–1183.

Brown, S. S., & Eisenberg, L. (1995). The best intentions: Unintended pregnancy and the well-being of children and families. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Bumpass, L. L. (1990). What’s happening to the family? Interactions between demographic and institutional change. Demography, 27, 483–498.

Bumpass, L. L., & Lu, H.-H. (2000). Trends in cohabitation and implications for children’s family contexts in the United States. Population Studies, 54, 29–41.

Bumpass, L. L., Raley, R. K., & Sweet, J. A. (1995). The changing character of stepfamilies: Implications of cohabitation and nonmarital childbearing. Demography, 32, 425–436.

Campbell, M. E. (2009). Multiracial groups and educational inequality: A rainbow or a divide? Social Problems, 56, 425–446.

Campbell, M. E., & Martin, M. A. (2016). Race, immigration and exogamy among the native born: Variation across communities. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 2, 142–161.

Chew, K. S. Y., Eggebeen, D. J., & Uhlenberg, P. R. (1989). American children in multiracial households. Sociological Perspectives, 32, 65–85.

Choi, K. H., & Goldberg, R. E. (2018). Fertility behavior of interracial couples. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80, 871–887.

Choi, K. H., & Seltzer, J. A. (2009). Race, ethnic, and nativity differences in the demographic significance of cohabitation in women’s lives (CCPR Working Paper Series 2009-004). Los Angeles: California Center for Population Research, University of California–Los Angeles.

Choi, K. H., & Tienda, M. (2017). Boundary crossing between first and remarriages. Social Science Research, 62, 302–317.

Davis, F. J. (1991) Who is Black? One nation’s definition. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Edin, K., Kefalas, M. J., & Reed, J. M. (2004). A peek inside the black box: What marriage means for poor unmarried parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 1007–1014.

England, P., Wu, L. L., & Shafer, E. F. (2013). Cohort trends in premarital first births: What role for the retreat from marriage? Demography, 50, 2075–2104.

Fu, V. K. (2008). Interracial-interethnic unions and fertility in the United States. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 783–795.

Goldstein, J. R., & Harknett, K. (2006). Parenting across racial and ethnic lines: Assortative mating pattern of new parents who are married, cohabiting, and in romantic relationships. Social Forces, 85, 121–143.

Gordon, M. M. (1964). Assimilation in American life: The role of race, religion, and national origins. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Gullickson, A. (2006). Education and Black-White interracial marriage. Demography, 43, 673–689.

Guzman, L., Wildsmith, E., Manlove, J., & Franzetta, K. (2010). Unintended births: Patterns by race and ethnicity and relationship type. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 42, 176–185.

Guzzo, K. B. (2014a). Trends in cohabitation outcomes: Compositional changes and engagement among never-married young adults. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76, 826–842.

Guzzo, K. B. (2014b). Fertility and the stability of cohabiting unions: Variation by intendedness. Journal of Family Issues, 35, 547–576.

Guzzo, K. B., & Hayford, S. R. (2014). Fertility and the stability of cohabiting unions: Variation by intendedness. Journal of Family Issues, 35, 547–576.

Herman, M. R., & Campbell, M. E. (2012). I wouldn’t, but you can: Attitudes toward interracial relationships. Social Science Research, 41, 343–358.

Heuveline, P., & Timberlake, J. M. (2004). The role of cohabitation in family formation: The United States in comparative perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 1214–1230.

Hiekel, N., Liefbroer, A. C., & Poortman, A.-R. (2014). Understanding diversity in the meaning of cohabitation across Europe. European Journal of Population, 30, 391–410.

Hummer, R. A., Hack, K. A., & Raley, R. K. (2004). Retrospective reports of pregnancy wantedness and child well-being in the United States. Journal of Family Issues, 25, 404–428.

Hummer, R. A., & Hamilton, E. R. (2010). Race and ethnicity in fragile families. Future of Children, 20(2), 113–131.

Kalmijn, M. (1998). Intermarriage and homogamy: Causes, patterns, trends. Annual Review of Sociology, 24, 395–421.

Kennedy, S., & Bumpass, L. L. (2008). Cohabitation and children’s living arrangements: New estimates from the United States. Demographic Research, 19, 1663–1692. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.47

Kreider, R. M. (2000, March). Interracial marriage and marital instability. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, Los Angeles, CA. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2000/demo/interracial-instability.pdf

Kroeger, R. A., & Williams, K. (2011). Consequences of Black exceptionalism? Interracial unions with Blacks, depressive symptoms, and relationship satisfaction. Sociological Quarterly, 52, 400–420.

Lichter, D. T., & Qian, Z. (2018). Boundary blurring? Racial identification among the children of interracial couples. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 677, 81–94.

Lichter, D. T., Sassler, S., & Turner, R. N. (2014). Cohabitation, post-conception unions, and the rise in nonmarital fertility. Social Science Research, 47, 134–147.

Lillard, L. A., & Waite, L. J. (1993). A joint model of marital childbearing and marital disruption. Demography, 30, 653–681.

Livingston, G., & Brown, A. (2017). Intermarriage in the U.S. 50 years after Loving v. Virginia (Social & Demographic Trends report). Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2017/05/18/intermarriage-in-the-u-s-50-years-after-loving-v-virginia/

Manning, W. D. (1993). Marriage and cohabitation following premarital conception. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 55, 839–850.

Manning, W. D. (2001). Childbearing in cohabiting unions: Racial and ethnic differences. Family Planning Perspectives, 33, 217–223.

Manning, W. D. (2015). Cohabitation and child wellbeing. Future of Children, 25(2), 51–66.

Manning, W. D., Brown, S. L., & Stykes, B. (2015). Trends in births to single and cohabiting mothers, 1980–2013 (NCFMR Family Profiles, No. FP-15-03). Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research. Retrieved from https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/FP-15-03-birth-trends-single-cohabiting-moms.pdf

Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (1995). Why marry? Race and the transition to marriage among cohabitors. Demography, 32, 509–520.

Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (2005). Measuring and modeling cohabitation: New perspectives from qualitative data. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 989–1002.

McLanahan, S. (2004). Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography, 41, 607–627.

Musick, K. (2002). Planned and unplanned childbearing among unmarried women. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 915–929.

National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). (2018). 2015–2017 National Survey of Family Growth: Public-use data files, codebooks, and documentation. Hyattsville, MD: CDC National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/nsfg_2015_2017_puf.htm

Parker, K., Horowitz, J. M., Morin, R., & Lopez, M. H. (2015). Multiracial in America: Proud, diverse, and growing in numbers (Social & Demographic Trends report). Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/06/11/multiracial-in-america/

Perelli-Harris, B. (2014). How similar are cohabiting and married parents? Second conception risks by union type in the United States and across Europe. European Journal of Population, 30, 437–464.

Perelli-Harris, B., Sigle-Rushton, W., Kreyenfeld, M., Lappegård, T., Keizer, R., & Berghammer, C. (2010). The educational gradient of childbearing within cohabitation in Europe. Population and Development Review, 36, 775–801.

Pew Research Center. (2012). The rise of intermarriage: Executive summary (Social & Demographic Trends report). Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2012/02/16/the-rise-of-intermarriage/

Qian, Z., & Lichter, D. T. (2007). Social boundaries and marital assimilation: Interpreting trends in racial and ethnic intermarriage. American Sociological Review, 72, 68–94.

Quillian, L., & Campbell, M. E. (2003). Beyond Black and White: The present and future of multiracial friendship segregation. American Sociological Review, 68, 540–566.

Raley, R. K. (2001). Increasing fertility in cohabiting unions: Evidence for the second demographic transition in the United States. Demography, 38, 59–66.

Rindfuss, R. R., & VandenHeuvel, A. (1990). Cohabitation: A precursor to marriage or an alternative to being single? Population and Development Review, 16, 703–726.

Roth, W. D. (2005). The end of the one-drop rule? Labeling of multiracial children in Black intermarriages. Sociological Forum, 20, 35–67.

Ryder, N. B. (1973). A critique of the National Fertility Survey. Demography, 10, 495–505.

Sassler, S. (2004). The process of entering into cohabiting unions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 491–505.

Schwartz, C. R. (2013). Trends and variation in assortative mating: Causes and consequences. Annual Review of Sociology, 39, 451–470.

Seltzer, J. A. (2000). Families formed outside of marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1247–1268.

Seltzer, J. A. (2004). Cohabitation in the United States and Britain: Demography, kinship, and the future. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 921–928.

Smock, P. J. (2000). Cohabitation in the United States: An appraisal of research themes, findings, and implications. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 1–20.

Sweeney, M. M., & Raley, R. K. (2014). Race, ethnicity, and the changing context of childbearing in the United States. Annual Review of Sociology, 40, 539–558.

Telles, E. E., & Ortiz, V. (2009). Generations of exclusion: Mexican Americans, assimilation, and race. New York, NY: Russell Sage.

Trussell, J., Vaughan, B., & Stanford, J. (1999). Are all contraceptive failures unintended pregnancies? Evidence from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. Family Planning Perspectives, 31, 246–247, 260.

Vasquez, J. (2014). The whitening hypothesis challenged: Biculturalism in Latino and non-Hispanic White intermarriage. Sociological Forum, 29, 386–407.

Yancey, G. (2007). Interracial contact and social change. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Zhang, Y., & Van Hook, J. (2009). Marital dissolution among interracial couples. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 95–107.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Western Faculty Research Development Fund. An earlier version of this article was presented at the 2019 annual meeting of the Population Association of America in Austin, Texas. We wish to thank Sarah Hayford for her insightful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed to the study concept and design. Kate Choi conducted the data analyses and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Both authors contributed to and reviewed subsequent versions of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethics and Consent

The authors report no ethical issues.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 106 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, K.H., Goldberg, R.E. The Social Significance of Interracial Cohabitation: Inferences Based on Fertility Behavior. Demography 57, 1727–1751 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-020-00904-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-020-00904-5