Abstract

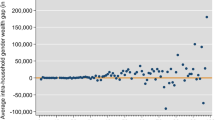

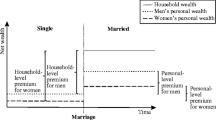

This article describes trends in parental wealth homogamy among union cohorts formed between 1987 and 2013 in Denmark. Using high-quality register data on the wealth of parents during the year of partnering, we show that the correlation between partners’ levels of parental wealth is considerably lower compared with estimates from research on other countries. Nonetheless, parental wealth homogamy is high at the very top of the parental wealth distribution, and individuals from wealthy families are relatively unlikely to partner with individuals from families with low wealth. Parental wealth correlations among partners are higher when only parental assets rather than net wealth are examined, implying that the former might be a better measure for studying many social stratification processes. Most specifications indicate that homogamy increased in the 2000s relative to the 1990s, but trends can vary depending on methodological choices. The increasing levels of parental wealth homogamy raise concerns that over time, partnering behavior has become more consequential for wealth inequality between couples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The data set used in this paper is based on several Danish administrative registers through social security numbers. These administrative microdata are located on specific computers at Statistics Denmark and may not be transferred to computers outside Statistics Denmark because of data security considerations. Researchers and their research assistants are allowed to use these data if their research project is approved by Statistics Denmark and if they are affiliated with a research institution accepted by Statistics Denmark. Currently, only researchers from research institutions in Denmark are allowed access to these data. Researchers at universities or other research institutions outside Denmark who wish to use these data may do so by visiting a Danish research institution or by cooperating with researchers working in Denmark. For researchers who want to analyze our data for replication purposes, we will provide guidance with regard to securing project approval at Statistics Denmark.

Notes

The category cohabited without children includes only households of two unrelated adults who had an age difference of less than 15 years and who were not related by family ties. A small minority of cases might therefore not regard romantically involved individuals. In robustness checks, we exclude unions that lasted less than three years to filter out such possible arrangements as much as possible, and results are unchanged; see Fig. A1 in the online appendix.

Figure B1 in the online appendix shows the distribution of cases that had no parental identification numbers by age and year. In the online appendix, we also discuss various robustness checks that address concerns about whether a changing age composition of the sample affected results (e.g., including sample weights to compensate for possible unequal probabilities of inclusion by birth year).

The results are robust. See Fig. C1 in the online appendix.

Tax-assessed housing values have historically not always reflected fully the market values at the time. Following Boserup et al. (2013) and Browning et al. (2013), we adjust tax-assessed housing values with a factor that reflects the average relationship between market values of traded houses and average tax-assessed values, thus arriving at an imputed estimate of the market value of housing wealth.

All wealth and income components are deflated with a GDP deflator to the 2010 price level.

Robustness checks calculating percentiles based on the wealth rank of all parents with children aged 18–35 produce practically identical results; see section D of the online appendix. This wealth rank is also used for our description of partnering probabilities by parental wealth (see Fig. 4).

In reality, we calculate the percentiles on the distribution of year normalized wealth. Thus, instead of wpi, y = u, we calculate (wpi, y = u − μy = u(wp)) / sdy = u(wp), meaning that we substract the average of parental wealth in the year of union formation and divide by its standard deviation. This results in the same distribution except that it allows us to pull forward the wealth of deceased parents in a comparable way and integrate it into the wealth distribution of the year that their child formed a union.

In these cases, parental wealth is normalized in the year both parents were still alive, and this value is subsequently used in the calculation of the parental wealth rank for each annual union cohort.

In 2018, one in four Danish couples were cohabiting rather than married, and the same cohabitation rate applies to couples with children, according to own calculations based on data from Statistics Denmark (www.statistikbanken.dk).

Information on tax-assessed housing values should, in principle, reflect market values for comparable traded houses. However, given that the majority of houses are not traded each year, the tax authorities’ estimated market values of houses may be too low (high), which can happen because specific unobserved characteristics (e.g., interior design, such as a new kitchen or bathrooms) are not taken into account by valuation authorities. Thus, the higher actual market values can translate into higher mortgages compared with the value of the house as indicated by the taxable values available in the data.

With financial deregulation and various reforms through the 1990s and early 2000s, house owners’ access to, for example, refinancing their mortgage debt, implied on average an increase in debt in relation to housing values (Browning et al. 2013).

For part of the sample, we do not observe all partnerships because partners are recorded only from 1986 onward. Some of the first partnerships we observe in the data might therefore in fact be a second, third, or higher-order partner of an individual.

An animated version is available at https://media.giphy.com/media/64anFirdCTXZYWRirY/giphy.gif. Section E of the online appendix also provides estimates of changes over time in the chances of partnering. The relationship between parental wealth and forming a first partnership during the observation period is relatively stable across union cohorts. The chances of forming a new partnership in any given year slightly declined for individuals with wealthy parents compared with individuals with less parental wealth due to increases in repartnering over time.

Part of the nonlinearity persists for the unions formed before 1997, which likely reflects changes in how some business assets were recorded. Before 1997, business assets were reported net of debts, and our indicator of assets could therefore still take on negative values only before 1997.

Robustness checks including controls for all parents’ and partners’ ages lead to similar results; see section G of the online appendix.

References

Balestra, C., & Tonkin, R. (2018). Inequalities in household wealth across OECD countries: Evidence from the OECD Wealth Distribution Database (OECD Statistics Working Papers No. 2018/01). Paris, France: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Barro, R. J., & Lee, J.-W. (2015). Education matters: Global schooling gains from the 19th to the 21st century. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Becker, G. S. (1973). A theory of marriage: Part I. Journal of Political Economy, 81, 813–846.

Becker, G. S. (1991). A treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Blossfeld, H. P. (2009). Educational assortative marriage in comparative perspective. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 513–530.

Boserup, S. H., Kopczuk, W., & Kreiner, C. T. (2013). Intergenerational wealth mobility: Evidence from Danish wealth records of three generations (Working paper). Copenhagen, Denmark: University of Copenhagen. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.593.4714&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Boserup, S. H., Kopczuk, W., & Kreiner, C. T. (2018). Born with a silver spoon? Danish evidence on wealth inequality in childhood. Economic Journal, 128(612), F514–F544.

Breen, R., & Andersen, S. H. (2012). Educational assortative mating and income inequality in Denmark. Demography, 49, 867–887.

Browning, M., Chiappori, P.-A., & Weiss, Y. (2014). Economics of the family. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Browning, M., Gørtz, M., & Leth-Petersen, S. (2013). Housing wealth and consumption: A micro panel study. Economic Journal, 123, 401–428.

Charles, K. K., & Hurst, E. (2002). The transition to home ownership and the Black-White wealth gap. Review of Economics and Statistics, 84, 281–297.

Charles, K. K., Hurst, E., & Killewald, A. (2013). Marital sorting and parental wealth. Demography, 50, 51–70.

Danish Economic Councils. (2016). Dansk økonomi [Danish economy], Chapter V. Copenhagen, Denmark: Danish Economic Councils.

Drefahl, S. (2012). Do the married really live longer? The role of cohabitation and socioeconomic status. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 462–475.

Eads, A., & Tach, L. (2016). Wealth and inequality in the stability of romantic relationships. Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 2(6), 197–224.

Fremeaux, N. (2014). The role of inheritance and labour income in marital choices. Population, 69, 495–530.

Gould, E. D., & Paserman, M. D. (2003). Waiting for Mr. Right: Rising inequality and declining marriage rates. Journal of Urban Economics, 53, 257–281.

Henz, U., & Mills, C. (2018). Social class origin and assortative mating in Britain, 1949–2010. Sociology, 52, 1217–1236.

Jakobsen, K., Jakobsen, K., Kleven, H., & Zucman, G. (2018). Wealth taxation and wealth accumulation: Theory and evidence from Denmark (NBER Working Paper No. 24371). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Kalmijn, M. (1991). Shifting boundaries: Trends in religious and educational homogamy. American Sociological Review, 56, 786–800.

Kalmijn, M. (1998). Intermarriage and homogamy: Causes, patterns, trends. Annual Review of Sociology, 24, 395–421.

Killewald, A. (2013). Return to being Black, living in the red: A race gap in wealth that goes beyond social origins. Demography, 50, 1177–1195.

Killewald, A., Pfeffer, F. T., & Schachner, J. N. (2017). Wealth inequality and accumulation. Annual Review of Sociology, 43, 379–404.

Kopczuk, W., & Lupton, J. P. (2007). To leave or not to leave: The distribution of bequest motives. Review of Economic Studies, 74, 207–235.

Kremer, M. (1997). How much does sorting increase inequality? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112, 115–139.

Lam, D. (1988). Marriage markets and assortative mating with household public goods: Theoretical results and empirical implications. Journal of Human Resources, 23, 462–487.

Monaghan, D. (2015). Income inequality and educational assortative mating: Evidence from the Luxembourg Income Study. Social Science Research, 52, 253–269.

Nielsen, H. S., & Svarer, M. (2009). Educational homogamy: How much is opportunities? Journal of Human Resources, 44, 1066–1086.

Pencavel, J. (1998). Assortative mating by schooling and the work behavior of wives and husbands. American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, 88, 326–329.

Pfeffer, F. T. (2011). Status attainment and wealth in the United States and Germany. In T. M. Smeeding, R. Erikson, & M. Jäntti (Eds.), Persistence, privilege, and parenting: The comparative study of intergenerational mobility (pp. 109–137). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Pfeffer, F. T. (2018). Growing wealth gaps in education. Demography, 55, 1033–1068.

Pfeffer, F. T., & Schoeni, R. F. (2016). How wealth inequality shapes our future. Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 2(6), 2–22.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the 21st century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Rauscher, E. (2016). Passing it on: Parent-to-adult child financial transfers for school and socioeconomic attainment. Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 2(6), 172–196.

Rosenfeld, M. J. (2008). Racial, educational and religious endogamy in the United States: A comparative historical perspective. Social Forces, 87, 1–31.

Rosenfeld, M. J., & Kim, B. S. (2005). The independence of young adults and the rise of interracial and same-sex unions. American Sociological Review, 70, 541–562.

Schneider, D. (2011). Wealth and the marital divide. American Journal of Sociology, 117, 627–667.

Schwartz, C. R. (2010). Earnings inequality and the changing association between spouses’ earnings. American Journal of Sociology, 115, 1524–1557.

Schwartz, C. R. (2013). Trends and variation in assortative mating: Causes and consequences. Annual Review of Sociology, 39, 451–470.

Schwartz, C. R., & Mare, R. D. (2005). Trends in educational assortative marriage from 1940 to 2003. Demography, 42, 621–646.

Smith, J. A., McPherson, M., & Smith-Lovin, L. (2014). Social distance in the United States: Sex, race, religion, age, and education homophily among confidants, 1985 to 2004. American Sociological Review, 79, 432–456.

Solon, G. (2004). A model of intergenerational mobility variation over time and place. In M. Corak (Ed.), Generational income mobility in North America and Europe (pp. 38–47). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Spilerman, S. (2000). Wealth and stratification processes. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 497–524.

Thompson, J., & Conley, D. (2016). Health shocks and social drift: Examining the relationship between acute illness and family wealth. Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 2(6), 153–171.

Torche, F. (2010). Educational assortative mating and economic inequality: A comparative analysis of three Latin American countries. Demography, 47, 481–502.

Weiss, Y., & Willis, R. (1997). Match quality, new information and marital dissolution. Journal of Labor Economics, 15, 293–329.

Wolff, E. N. (2017). Household wealth trends in the United States, 1962 to 2016: Has middle class wealth recovered? (NBER Working Paper No. 24085). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Acknowledgments

Sander Wagner was supported in this research by a grant of the French National Research Agency (ANR), Investissements d’Avenir (Labex ECODEC-ANR-11-LABX-0047). Mette Gørtz appreciates generous funding from the Danish National Research Foundation through its grant (DNRF-134) to CEBI, Center for Economic Behavior and Inequality. Diederik Boertien acknowledges research funding from the Beatriu de Pinos program of the Generalitat de Catalunya (2016-BP-00121) as well as the EQUALIZE project led by Iñaki Permanyer (ERC-2014-STG grant agreement No. 637768). We also appreciate input from seminar attendants at the Crest Sociology Lab and the Center for Demographic Studies. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.W. and D.B. developed the research idea; S.W. managed and analyzed data; and S.W., D.B., and M.G. wrote and edited the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics and Consent

The authors report no ethical issues.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 661 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wagner, S., Boertien, D. & Gørtz, M. The Wealth of Parents: Trends Over Time in Assortative Mating Based on Parental Wealth. Demography 57, 1809–1831 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-020-00906-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-020-00906-3