Abstract

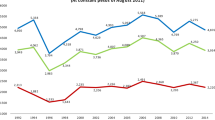

Scholars have increasingly drawn attention to rising levels of income inequality in the United States. However, prior studies have provided an incomplete account of how changes to specific transfer programs have contributed to changes in income growth across the distribution. Our study decomposes the direct effects of tax and transfer programs on changes in the household income distribution from 1967 to 2015. We show that despite a rising Gini coefficient, lower-tail inequality (the ratio of the 50th to 10th percentile) declined in the United States during this period due to the rise of in-kind and tax-based transfers. Food assistance and refundable tax credits account for nearly all the income growth between 1967 and 2015 at the 5th percentile and roughly one-half the growth at the 10th percentile. Moreover, income gains near the bottom of the distribution are concentrated among households with children. Changes in the income distribution were far less progressive among households without children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

All data are available through the public versions of the U.S. Current Population Survey. Full replication code is available upon request to the authors.

Notes

Pre-tax money income includes cash transfers from programs such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) as well as pension support from Social Security. It includes income from child support and private transfers across households but does not include child support paid or remittances to family members outside the country. It should not be confused with market income (earnings from paid labor only), which comparative studies often apply in pre-post analyses.

There are numerous alternate ways to adjust for household size, as detailed by Buhmann et al. (1988). When household income is adjusted for household size, we assume some economy of scale whereby household members share fixed costs such that each additional member lowers the household’s cost per capita. To estimate this, household income is typically divided by household size raised to some scale elasticity between 0 and 1 (Household income/household sizee, where e equals the scale elasticity). When elasticity is 0, there is no adjustment for household size, and thus each household member requires the same dollar amount to afford the same level of consumption. When elasticity is 1, there are no economies of scale, and so each member has equivalent costs regardless of household size. We choose a commonly used approach that sets elasticity between the two extremes at .5 (Johnson et al. 2005).

Given evidence of underreporting of SNAP benefits in the CPS ASEC, the actual effects of SNAP on income growth at the bottom of the distribution are likely larger than they appear in Fig. 4.

References

Allison, P. D. (1978). Measures of inequality. American Sociological Review, 43, 865–880.

Atkinson, A. B. (1970). On the measurement of inequality. Journal of Economic Theory, 2, 244–263.

Atkinson, A. B., & Jenkins, S. P. (2020). A different perspective on the evolution of UK income inequality. Review of Income and Wealth, 66, 253–266.

Atkinson, A. B., Rainwater, L., & Smeeding, T. M. (1995). Income distribution in OECD countries: Evidence from the Luxembourg Income Study. Paris, France: OECD.

Blank, R. M., & Greenberg, M. H. (2008). Improving the measurement of poverty (Policy Brief No. 2008-17). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Bofinger, P., & Scheuermeyer, P. (2019). Income distribution and aggregate saving: A non-monotonic relationship. Review of Income and Wealth, 65, 872–907.

Buhmann, B., Rainwater, L., Schmaus, G., & Smeeding, T. M. (1988). Equivalence scales, well-being, inequality, and poverty: Sensitivity estimates across ten countries using the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) database. Review of Income and Wealth, 34, 115–142.

Burkhauser, R. V., & Simon, K. I. (2008). Who gets what from employer pay or play mandates? Risk Management and Insurance Review, 11, 75–102.

Congressional Budget Office. (2018). The distribution of household income, 2015 (CBO Report No. 54646). Retrieved from https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2018-11/54646-Distribution_of_Household_Income_2015_0.pdf

DeNavas-Walt, C., & Proctor, B. (2015). Income and poverty in the United States: 2014 (Current Population Reports, P60-252). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Duncan, G. J., Kalil, A., & Ziol-Guest, K. M. (2013, April). Increasing inequality in parent incomes and children’s completed schooling: Correlation or causation? Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, New Orleans, LA.

Feenberg, D., & Coutts, E. (1993). The TAXSIM model. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 12, 189–194.

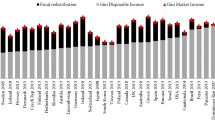

Filauro, S., & Parolin, Z. (2019). Unequal unions? A comparative decomposition of income inequality in the United States and European Union. Journal of European Social Policy, 29, 545–563.

Förster, M. F., & Vleminckx, K. (2004). International comparisons of income inequality and poverty: Findings from the Luxembourg Income Study. Socio-Economic Review, 2, 191–212.

Fox, L., Wimer, C., Garfinkel, I., Kaushal, N., & Waldfogel, J. (2015). Waging war on poverty: Poverty trends using a historical supplemental poverty measure. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 34, 567–592.

Gornick, J. C., & Jäntti, M. (2016). Poverty. Pathways Magazine: The poverty & inequality report (Special issue), 16–24.

Gottschalk, P., & Smeeding, T. M. (1997). Cross-national comparisons of earnings and income inequality. Journal of Economic Literature, 35, 633–687.

Guillaud, E., Olckers, M., & Zemmour, M. (2020). Four levers of redistribution: The impact of tax and transfer systems on inequality reduction. Review of Income and Wealth, 66, 444–466.

Hardy, B., Smeeding, T., & Ziliak, J. P. (2018). The changing safety net for low-income parents and their children: Structural or cyclical changes in income support policy? Demography, 55, 189–221.

Iceland, J. (2013). Poverty in America: A handbook (3rd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Institute for Research on Poverty. (2019). Understanding benefit cliffs and marginal tax rates (IRP Fast Focus Research/Policy Brief No. 43–2019). Madison, WI: Institute for Research on Poverty.

Johnson, D., Smeeding, T. M., & Torrey, B. B. (2005). United States inequality through the prisms of income and consumption. Monthly Labor Review, 128(4), 11–24.

Jouini, N., Lustig, N., Moummi, A., & Shimeles, A. (2018). Fiscal policy, income redistribution, and poverty reduction: Evidence from Tunisia. Review of Income and Wealth, 64(Suppl. 1), S225–S248.

Kaushal, N., Magnuson, K., & Waldfogel, J. (2011). How is family income related to investments in children’s learning? In G. J. Duncan & R. J. Murnane (Eds.), Whither opportunity? Rising inequality schools, and children’s life chances (pp. 187–206). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Kornrich, S., & Furstenberg, F. (2013). Investing in children: Changes in parental spending on children, 1972–2007. Demography, 50, 1–23.

Luxembourg Income Study (LIS). (2016). Disposable household income [Data set]. Esch-Belval, Luxembourg: LIS Cross-National Data Center.

Meyer, B. D., & Mittag, N. (2015). Using linked survey and administrative data to better measure income: Implications for poverty, program effectiveness and holes in the safety net (NBER Working Paper No. 21676). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Meyer, B. D., & Sullivan, J. X. (2013). Winning the war: Poverty from the Great Society to the Great Recession (NBER Working Paper No. 18718). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Milanovic, B. (2016). Global inequality: A new approach for the age of globalization. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Moffitt, R. A., & Pauley, G. (2018). Trends in the distribution of social safety net support after the Great Recession (Working paper). Stanford, CA: Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality. Retrieved from https://www.russellsage.org/sites/default/files/safety-net-distribution-trends.pdf

Moffitt, R., & Scholz, J. K. (2010). Trends in the level and distribution of income support. Tax Policy and the Economy, 24, 111–152.

National Research Council. (1995). Measuring poverty: A new approach. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Newman, K. S., & O’Brien, R. L. (2011). Taxing the poor: Doing damage to the truly disadvantaged. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Nolan, B., Roser, M., & Thewissen, S. (2019). GDP per capita versus median household income: What gives rise to the divergence over time and how does this vary across OECD countries? Review of Income and Wealth, 65, 465–494.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2011). Divided we stand: Why inequality keeps rising. Paris, France: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2015). In it together: Why less inequality benefits all. Paris, France: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264235120-en

Parolin, Z. (2019). The effect of benefit underreporting on estimates of poverty in the United States. Social Indicators Research, 144, 869–898.

Parolin, Z., & Brady, D. (2019). Extreme child poverty and the role of social policy in the United States. Journal of Poverty and Social Justice, 27, 3–22.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Ravallion, M., & Chen, S. (2001). Measuring pro-poor growth (English) (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. WPS2666). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Reardon, S. F. (2011). The widening academic achievement gap between the rich and the poor: New evidence and possible explanations. In G. J. Duncan & R. J. Murnane (Eds.), Whither opportunity? Rising inequality, schools, and children’s life chances (pp. 91–116). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Saez, E., & Zucman, G. (2016). Wealth inequality in the United States since 1913: Evidence from capitalized income tax data. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131, 519–578.

Stanley, M., Floyd, I., & Hill, M. (2016). TANF cash benefits have fallen by more than 20 percent in most states and continue to erode (Technical report). Washington, DC: Center on Budget & Policy Priorities.

Wimer, C., Fox, L., Garfinkel, I., Kaushal, N., & Waldfogel, J. (2016). Progress on poverty? New estimates of historical trends using an anchored supplemental poverty measure. Demography, 53, 1207–1218.

Acknowledgments

Liana Fox contributed to this article in her personal capacity. The views expressed in this research, including those related to statistical, methodological, technical, or operational issues, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official positions or policies of the U.S. Census Bureau. The authors also wish to thank Irwin Garfinkel, Neeraj Kaushal, and Jane Waldfogel for their contributions to creating the data underlying this study, and also the anonymous reviewers of the study for their valuable feedback. Funding from the Annie E. Casey Foundation and The JPB Foundation is gratefully acknowledged, though all opinions and errors are the authors’ alone.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wimer, Fox, Fenton, and Jencks led initial writing and data analysis. Parolin led subsequent writing and data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Ethics and Consent

The authors report no concerns relating to ethics or consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 937 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wimer, C., Parolin, Z., Fenton, A. et al. The Direct Effect of Taxes and Transfers on Changes in the U.S. Income Distribution, 1967–2015. Demography 57, 1833–1851 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-020-00903-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-020-00903-6