Abstract

Aims

Consequences of climate change and land use intensification on the nitrogen (N) cycle of organic-matter rich grassland soils in the alpine region remain poorly understood. We aimed to identify fates of fertilizer N and to determine the overall N balance of an organic-matter rich grassland in the European alpine region as influenced by intensified management and warming.

Methods

We combined 15N cattle slurry labelling with a space for time climate change experiment, which was based on translocation of intact plant-soil mesocosms down an elevational gradient to induce warming of +1 °C and + 3 °C. Mesocosms were subject to either extensive or intensive management. The fate of slurry-N was traced in the plant-soil system.

Results

Grassland productivity was very high (8.2 t - 19.4 t dm ha−1 yr−1), recovery of slurry 15N in mowed plant biomass was, however, low (9.6–14.7%), illustrating low fertilizer N use efficiency and high supply of plant available N via mineralization of soil organic matter (SOM). Higher 15N recovery rates (20.2–31.8%) were found in the soil N pool, dominated by recovery in unextractable N. Total 15N recovery was approximately half of the applied tracer, indicating substantial loss to the environment. Overall, high N export by harvest (107–360 kg N ha−1 yr−1) markedly exceeded N inputs, leading to a negative grassland N balance.

Conclusions

Here provided results suggests a risk of soil N mining in montane grasslands, which increases both under climate change and land use intensification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the pre-alpine and alpine region of south Germany, grasslands cover over one million hectares (BMLEV 2012), and are of similar importance in comparable areas in Austria, Italy and Switzerland. Permanent grassland soils, particularly at higher elevations, store extraordinarily large amounts of soil organic carbon (SOC) and total nitrogen (TN) (Wiesmeier et al. 2013). Most grasslands in the pre-alpine region are used for dairy and cattle farming, with diverse management intensities. The high SOC and TN content facilitates economic soil functions such as high forage production (Blum 2005; Rabot et al. 2018) while also providing ecological soil functions such as water and nutrient retention and a high diversity of plant species (Wilson et al. 2012).

By extending the length of growing seasons, climate warming increases the productivity of grasslands (Berauer et al. 2019; Fraser et al. 2015; Fu et al. 2019; Kühnel et al. 2019; Sebastià et al. 2008), which may also facilitate increased management intensity by the farmers. However, it was also shown that climate change can lead to decreasing soil N and C pools (Kühnel et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2016; Wiesmeier et al. 2013) posing risk on soil fertility of managed montane grasslands on the long term. Furthermore, the dominant N input to montane grassland systems in the alpine and pre-alpine region is the fertilization with liquid cattle slurry, a N fertilization form which can result in high gaseous losses especially under warming (Zistl-Schlingmann et al. 2019). This is of particular importance in the European alpine and pre-alpine region, where climate warming is occurring at twice the rate compared to global average, a trend that is expected to continue or even accelerate in the coming decades (Pepin et al. 2015; Smiatek et al. 2009; Wagner et al. 2013).

Effects of management (i.e. intensive vs. extensive fertilization with cattle slurry along with high versus low mowing frequency) and climate change on grassland productivity (Berauer et al. 2019; Fraser et al. 2015; Fu et al. 2019; Sebastià et al. 2008), associated N exports, N loss pathways such as N leaching (Fu et al. 2017; de Vries et al. 2012), gross N mineralization rates (Wang et al. 2016) and nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions (Butterbach-Bahl and Dannenmann 2012; Cantarel et al. 2011; Cardenas et al. 2019; Wolf et al. 2010) are increasingly understood. So far, few studies investigated the N use efficiency of grasslands fertilized with slurry (Hoekstra et al. 2010), N fates in the plant-soil system of grasslands (Bardgett et al. 2003; Harrison et al. 2007, 2008; Hart et al. 1993; Xu et al. 2011), and the overall N balance of grassland soils (Ammann et al. 2009). However, the influence of climate warming, hitherto remained unexplored. Both plant N use efficiency as well as stabilization of fertilizer N in soil largely determine slurry-N losses along gaseous and leaching pathways. Development of new climate-smart land management options targeted to maintain soil N stocks ultimately rely on a detailed understanding of the fate of fertilizer N in the plant-soil system. This mandates an increased understanding of plant N use efficiency and total N losses in montane grassland management.

Most of the available literature on tracing of 15N labeled fertilizer report on crop systems (Jensen et al. 2000; Muñoz et al. 2004; Paul and Beauchamp 1995; Rocha et al. 2019; Zhou et al. 2016) or the use of mineral N rather than organic fertilizer such as cattle slurry (Bardgett et al. 2003; Christian et al. 1997; Harrison et al. 2007, 2008; Hart et al. 1993; Rowlings et al. 2016; Scheiner et al. 2002; Xu et al. 2011), thereby leaving a knowledge gap with regard to managed grasslands.

Attributable to the higher surface to biomass ratio of microbes compared to plants (Hodge et al. 2000), microorganisms show substantially faster initial uptake of N, giving them a competitive advantage over plants (Kuzyakov and Xu (2013). However, these short-term competitive disadvantages of plants can give way to long-term competitive advantages due to the short life cycle of microorganisms in the rhizosphere and the much larger mean residence time of N in plants. For instance, on arable soils with low SOC and TN contents, 15N recovery in microbial biomass was only higher during the first four hours after tracer application, whereas within one week plants took up 45–80% of applied 15N (Inselsbacher et al. 2010). Various other 15N tracing studies in grasslands (Bardgett et al. 2003; Christian et al. 1997; Harrison et al. 2007, 2008; Hart et al. 1993; Rowlings et al. 2016; Scheiner et al. 2002; Xu et al. 2011) show high variance in total 15N recovery in the plant biomass, with recovery rates ranging from 2 to 50%. Due to the relatively longer N residence time in plants, their aboveground productivity and N export during harvest is crucial for the N balance of grasslands.

Furthermore, long term studies tracing the fate of fertilizer 15N after multiple fertilization events and on longer time scales than days to weeks are still missing for grasslands. This lack of knowledge hampers a thorough evaluation of current management of grasslands and leaves adaptations needed in a changing climate as a major unknown. Increased climate change effect in the alpine region even increases the need for this evaluation in montane grasslands. In this study, we offer new insights on slurry-N use efficiency and the fates of slurry-N in the plant-soil microbe system of montane grasslands.

In a downslope translocation experiment, we evaluate plant productivity, slurry-N use efficiency, slurry-N fates and the N balance in a montane grassland for different magnitudes of climate warming and intensities of land management, namely N fertilization and mowing frequency. We repeatedly applied 15N labeled cattle slurry and traced the 15N signal in mesocosms over more than a full year. We hypothesize that climate change would increase soil N mineralization and productivity, leading to increased N export and thus, to negative ecosystem N balances. Furthermore, we expected that intensive management (five instead of two fertilization-harvest cycles for extensive management) would counteract the risk of N mining (deficit in the N balance causing a decrease of soil organic nitrogen (SON)) by increased N addition and stabilization in soil organic matter (SOM).

Material and methods

Study sites and experimental design

This study was conducted in the alpine/pre-alpine region of southern Germany along an elevational gradient descending from Esterberg (1260 m a.s.l.) via Graswang (860 m a.s.l.) to Fendt (600 m a.s.l.). The two higher sites are located in valley bottoms with mountainous surroundings up to 2000 m in elevation, however, sampling sites themselves are all characterized by flat topography. The elevational gradient was used to simulate climate change conditions for intact plant-soil mesocosms originating from Esterberg (1260 m a.s.l.) via downslope translocation to the sites at lower elevation. While this climate change treatment resembles projected temperature increases and summer precipitation reduction as projected by regional climate modelling until mid of the twenty-first century (Gobiet et al. 2014; Smiatek et al. 2009; Warscher et al. 2019), it does not include free air CO2 enrichment. The control site Esterberg (47°31’ N, 11°09′ E), in the following referred to as H1260 (H: Highest site, 1260 m a.s.l.), is a typical montane grassland in the Northern Limestone Alps of southern Germany used for forage production or grazing of cattle. The soil at Esterberg is a Phaeozem (IUSS Working Group WRB 2015) with high SOC content of 150 mg g−1 and TN content of 16 mg g−1 in the 0–15 cm topsoil, a low bulk density of 0.6 g cm−3 and a pH of 6.1. Plant roots occurred mainly in the upper 15 cm of the soil. The soil is characterized by a 30 cm thick Ah horizon, followed by the calcareous parent material. The plant community composition was typical for species-rich montane pastures of this region; notably only ~8% of the species were legumes. The most dominant species were Festuca pratensis (Huds.) Poaceae, Agrostis capillaris (L.) Poaceae, Carum carvi (L.) Apiaceae and Ranunculus acris (L.) Ranunculaceae. The abundant legumes were Trifolium pratense (L.) Fabaceae and Trifolium repens (L.) Fabaceae. Mean annual temperature and precipitation during the experimental period was 6.4 °C and 1690 mm, respectively. The Graswang site (860 m a.s.l., 47°57’ N, 11°03′ E; used for simulation of moderate climate change; in the following referred to as M860) had an average air temperature of 7.4 °C and 1626 mm precipitation during the experimental period. Fendt (600 m a.s.l, 47.83° N, 11.07° E; used for simulation of intense climate change; in the following referred to as L600), showed an average air temperature of 9.4 °C and 1134 mm of precipitation.

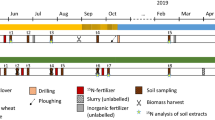

In total, 69 intact plant-soil mesocosms (height 25 cm, diameter 17 cm) were taken at the Esterberg site from three replicated sampling plots of 60 m2 area each. In order to expose the soils and plants to the two climate change treatments, one third of the mesocosms were operated as control at H1260 and one third each translocated to M860 and L600, respectively. After translocation, all mesocosms underwent either intensive or extensive management (cutting times and frequency, surface fertilizer application of liquid cattle slurry, see Fig. 1) according to the local farmer’s practice. Management at the site of origin prior to translocation was extensive use with one fertilizer application in spring, one harvest in July and subsequent cattle grazing for the rest of the growing season. Translocation was carried out in August 2016 and experiments started after an equilibration period of 10 months with the first 15N labeling and sampling in May 2017. The full factorial design (H1260, M860, L600 with each intensive and extensive management) resulted in six different treatments.

Production and use of 15N labeled cattle slurry

The 15N labeling of the mesocosms was conducted via the application of 15N enriched liquid cattle slurry. Slurry was supplied by the local farmer at the Fendt field site and analyzed for N compounds by a commercial laboratory (Raiffeisen-Laborservice, Ormont, Germany). Based on these analyses the intended 15N enrichment of the slurry was ca. 5% and executed via the addition of 99% 15N enriched ammonium sulfate and urea in equal N amounts to mimic fresh cattle slurry and label around ¾ of all N forms in the slurry. The unlabeled organic forms of N in the slurry are expected to experience similar fates in the N cycle after their mineralization as the labeled N compounds. Also, the calculation of recovery rates is based on actual addition of 15N, therefore, method inherent bias of unlabeled N compounds in the slurry is relatively small. The used cattle slurry on average contained 4.2% total N, which was 53% NH4+-N and 47% organic-N (including urea). Addition of 15N label marginally increased the N content of slurry by 3.5% on average.

Immediately prior to fertilization of the mesocosms, the 15N tracer was added to the slurry in a polyethylene barrel and vigorously shaken to ensure a homogenous mixture with the slurry. Each mesocosm was fertilized with an amount of 40 ml liquid manure per fertilization event, representing farmers practice with an application rate of 1.8 m3 ha−1. This resulted in an addition of 5.7 mg 15N in excess of natural abundance per mesocosm and fertilization event. Also following the farmer’s practice in the study region, intensive management of mesocosms was characterized by four fertilization events (146 kg N ha−1 yr−1) and three cuts at the H1260 control site, while higher biomass production at both sites at lower elevation led to an additional fertilization (176 kg N ha−1 yr−1) and harvest event in September (Fig. 1). In contrast to these elevation-and thus climate induced differences in intensive management practices, extensive management was identical at all three sites, with two fertilization (76 kg N ha−1 yr−1) and two harvest events per year. All fertilizations of the year 2017 were enriched in 15N, while fertilization in 2018 was conducted without 15N enrichment. A final mesocosm harvest was conducted for all treatments in June 2018. Labeling and sampling timelines are displayed in Fig. 1. Note that the timing of fertilization and cutting at the sites differed mainly in the beginning of the growing season due to the delayed vegetation development at H1260 compared to M860 and L600.

Sampling and sample preparation

Sampling was conducted at each cutting event by full destructive harvests of a set of three entire mesocosms for each treatment (climate, management) with the three harvested mesocosms originating each from one of the three different sampling plots at H1260 (see above). To facilitate sampling, mesocosms were brought to the laboratories of KIT-IMK-IFU in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany with the full destructive harvest of soils and plants being completed at the same day. To do so, the soil column was pushed out of the stainless steel core with a special manual device. Aboveground biomass was then removed by cutting the turf. Subsequently, the soil column was cut at 15 cm depth with the last 10 cm depth of the mesocosm being discarded. This was motivated because main rooting depth did not extend beyond 15 cm. Soil was homogenized by hand in a bucket for at least 10 min. Roots were picked from the homogenized soil for 20 min and subsequently washed with tap water. Please note, that used cylinders (17 cm diameter) could cause method inherent bias of root development, which is however consistent in all treatments. Soil, aboveground biomass, and roots were dried at each substances’ best practice (details follow in the next section) before further analyses were conducted.

Plant biomass

Above- and belowground plant biomass samples were dried at 55 °C to a constant weight directly after sample preparation. Dry plant biomass was sent to the BayCEER – Laboratories for Isotope and Biogeochemistry in Bayreuth for analysis of 15N enrichment and N concentration through elemental analyzer isotope-ratio-mass-spectrometry (EA-IRMS). For these measurements, each sample was homogenized, ground to a fine powder with a ball mill (Retsch Schwingmühle MM2, Haan, Germany) and stored until analysis in a desiccator with silica gel. Relative N isotope abundances and total N concentration of samples was measured in dual element analysis mode with an elemental analyzer (Carlo Erba Instruments 1108, Milano, Italy) coupled to a continuous flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer (delta S; Finnigan MAT, Bremen, Germany) via a ConFlo III open- split interface (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) as described by Bidartondo et al. (2004).

N compounds in soil

For the determination of NH4+ and NO3−, microbial biomass N (MBN) and dissolved organic N (DON) concentrations as well as the pool-specific 15N enrichment, samples of 80 g of homogenized fresh soil were extracted with 0.5 M K2SO4 solution at the harvest day, while 40 g of fresh soil were fumigated with ethanol-free chloroform and extracted the following day to determine MBN. The soil: extractant ratio was 1:2. Soil extracts were directly frozen until further processing. Ammonium and NO3− concentrations were determined by the commercial laboratory Dr. Janssen GmbH (Gillersheim, Germany) from a subsample of the soil extracts. Soil extracts were also analyzed for DOC and TN concentrations (Multi N/C 3100, Analytik Jena, Germany) according to Dannenmann et al. (2016). The 15N enrichment in NH4+, NO3−, and DON was analyzed by sequential diffusion on acid filter traps as described in detail by Guo et al. (2013). Microbial biomass N and 15N was determined from the respective differences in total 15N in fumigated and non-fumigated extracts (Guo et al. 2013) without applying a correction factor for extraction efficiency (kEN). All isotopic analyses of 15N enrichment in dissolved N compounds of soil extracts were conducted in the Center of Stable Isotope Analysis of KIT-IMK-IFU in Garmisch-Partenkirchen as described in Wang et al. (2016).

Recovery of 15N in unextractable N (i.e., TN minus DON, mineral N and MBN) was determined via the measurement of 15N enrichment in TN via solid matter analysis using an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Delta PlusXP, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) coupled to an elemental analyzer (Flash EA, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) (EA-IRMS) in the Center of Stable Isotope Analysis at KIT/IMK-IFU in Garmisch-Partenkirchen. SOC and TN concentrations of the bulk soil were determined using an elemental analyzer (VarioMax cube, Elementar, Langenselbold, Germany).

N leaching rates

The leaching of mineral N was determined from accumulation of NH4+ and NO3− on resin bags. For this purpose, bags containing ion-exchange resins (45 g of Amberlite, IR 120 [Na + −ion exchanger resin] and 45 g Dowex 1× 8 [Cl−−ion exchanger resin]) were placed under three mesocosms per treatment on March 20th and harvested after the first vegetation period in November. Resin bags were brought to the labs of KIT-IMK-IFU in Garmisch-Partenkirchen and extracted with 1 M K2SO4 solution. The extracts were used for measurements of TN concentrations as described above, but since N leaching losses were a minor flux (~1 kg N ha−1 growing season−1, Table 1) in the grassland N balance, no 15N analyses were conducted.

Gross N mineralization

Gross N mineralization rates were measured in a parallel experiment with intact soil cores extracted from big mesocosms (30 cm diameter, 30 cm depth), which were treated similarly as the mesocosms in this study, only with 15N natural abundance slurry. The 15N pool dilution technique as described by Wang et al. (2016) was used. Measurements were carried out in June and October 2017 on soil cores with 5 cm diameter and 4 cm depth. Each soil core received 30 15N injections applied through a multi-injector system in three depths in order to ensure homogenous 15N labeling. Sampling depth was 1–5 cm, the turf was discarded.

Meteorological data

Precipitation data for the Esterberg site was gathered with three replicated rain gauges (Rain Collector II, Davis Instruments, Hayward, CA, USA). Additionally, the study site was equipped with an Atmos41 (Meter Environment, Munich, Germany) all-in-one weather station and a snow monitoring station (SnoMoS) developed by Pohl et al. (2014) used for snow height and precipitation measurements during the winter period. As part of the TERENO Pre-alpine Observatory (Kiese et al. 2018), the sites in Graswang and Fendt are both fully equipped with eddy-covariance stations and Pluvio (Ott Hydromet, Germany) rain gauges.

Calculation of 15N recovery

Excess 15N amount (mg) in all investigated pools was calculated using the following equation.

where Npool is the amount of N [mg N mesocosm−1] in the plant or depth-specific soil N pool and 15NL is the enrichment (atom% 15N) of the respective N pool. We used 0.3663% as the natural abundance of 15N; errors induced by possible slight variations of 15N natural abundance were negligible due to the high enrichment obtained from 15N slurry labeling. Dividing 15N excess amount in the analyzed pools by the cumulative 15N excess addition through slurry fertilization at the sampling time (5.7 mg 15N excess per fertilization event and mesocosm) revealed the 15N excess recovery, which was expressed as a percentage. Recovery in aboveground biomass (AGB) was always calculated with cumulated 15N excess, thereby considering the preceding samplings to account for the exported 15N excess via biomass harvest.

Nitrogen balance

The N balance components slurry-N-input, plant-N-harvest and total slurry-N-loss (based on percentage of unrecovered 15N multiplied by N input through slurry application) were calculated with the data gathered during the experiment. Total N deposition of 33 ± 7 kg N ha−1 yr−1 was reported by LfU (2011) for the Bavarian pre-alpine region based on measurements at several fertilized grassland sites. Biological Nitrogen fixation (BNF) was estimated based on the measured contribution of legumes to total plant biomass yield and previously published relationships between legume abundance and BNF rates (Jacot et al. 2000) obtained for comparable grassland sites in Switzerland. In the latter study, a contribution of 5 to 15% of legume abundance lead to a contribution of fixed N to plant biomass N ranging from 9 to 16%, equaling 1–26 kg N ha−1. Applying these relationships, the observed proportion of legumes to total dry matter yield (3%) translated into BNF estimates of 15 kg N ha−1 yr−1 in this study.

Statistical analysis

ANOVA requirements of normality and homoscedasticity were not fulfilled, therefore the non -parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to test for effects of climate and land management treatments on the measured parameters. Management treatments were only compared when joint samplings of intensive and extensive treatments were carried out (July 2017, August/September 2017 and June 2018, see Fig. 1) as well as for average recovery of all single samplings over the whole experimental period. For comparison of climate treatments during single sampling events, samplings of intensive land-use in August 2017 at M860, and L600 and September for H1260 were treated as the same sampling (third harvest, see Fig. 1). Fourth harvest at M860, and L600 was treated separately, without comparison to the H1260 site. All statistical analyses were carried out with IBM SPSS 25.0 (IBM, NY, USA).

Results

Site meteorological data

Average air temperature and precipitation during the vegetation period (01.04.2017–31.10.2017) was 9.7 °C and 1180 mm, 11.0 °C and 1240 mm and 12.5 °C and 890 °C at H1260, M860 and L600, respectively. Number of vegetation days (average daily air temperature > 5 °C) during the vegetation period in 2017 was 198 (H1260), 212 (M860) and 235 (L600). Monthly average temperature and precipitation distribution over time are displayed in Fig. 2.

Nitrogen pools

Aboveground biomass production (AGB), N concentration and export

Annual AGB production in 2017 at the control site was 8 t DM ha−1 in the extensive treatment and 14 t DM ha−1 in the intensive treatment (Table 2). Under intensive management and moderate climate change simulation (transfer to M860), plant biomass production increased to around 19 t ha−1 with no further increase following translocation to L600. In contrast, climate change simulation did not affect AGB yields under extensive management in 2017. Nitrogen concentration in AGB showed little variation across the treatments of this study and varied between 0.9 and 2.7% (Table 3).

Biomass yields and N concentration translated to average annual plant N export in 2017 of 156 ± 39 and 302 ± 61 kg N for extensive and intensive management, respectively (Table 4). Plant N export via harvest generally exceeded fertilizer N inputs (extensive: 76 kg, intensive: 146–174 kg). Cumulative N exports were approximately doubled in the intensive compared to the extensive treatment and experimental climate change generally increased N harvest exports. However, highest N exports were observed in the moderate climate change treatment while N exports under simulation of intensive climate change did not further increase or even declined compared to M860.

Root biomass and N concentrations

Root biomass did not show differences between treatments, neither for climate nor management, with an average dry mass of 3.1 t ha−1 (Supplementary Table 1). However, N concentration of roots was higher in the extensive treatment with an average of 1.5 ± 0.1% while it was at 1.2 ± 0.1% in the intensive treatment (Supplementary Table 2). This management effect was present under all climate change treatments.

Soil N pools

The total N stocks in the top 15 cm of soil were ~ 10 t N ha−1 and did not differ across management and climate treatments, which indicates homogenous soil conditions across treatments at the beginning of the experiment. Nitrogen stocks for the soil column down to the parent material (40 cm) were ca. 25 t N ha−1.

Management treatments showed a similar course over time for NH4+, NO3− and DON, while climate change treatments showed mostly higher concentrations than the control site in 2017. The temporal course of DON and NH4+ followed the same trends over the whole measurement period (Supplementary Figure 1).

Gross N mineralization

Mean gross N mineralization rates ranged between 5.5 and 9.4 kg N ha−1 d−1 in the 1–5 cm soil depth and did not show consistent differences across climate and land use treatments (Table 5).

15N recovery from labeled fertilizer

Plant 15N recovery

Recovery of 15N labeled fertilizer in AGB was between 4.8 and 24.9% with an average recovery of 11.6% across all management and climate treatments. Belowground biomass generally showed lower recovery between 0.6 and 13.3%, averaging at 3.4% (Supplementary Table 3). Management had significant impacts on 15N fertilizer recovery in AGB at several sampling dates. At M860 intensive treatment showed significantly higher recovery at the first and last sampling, while the summer sampling in 2017 revealed higher recovery in the extensive treatment for both M860 and also L600, while the opposite was found at H1260 with higher recovery in the intensive treatment in the summer sampling. Similar to M860, H1260 also showed higher recovery for the intensive treatment during the last sampling after one year.

Average 15N recovery in the AGB was not different between climate treatments for both land use managements. The single samplings however revealed some differences between climates. In the intensively managed mesocosms, samplings during peak growing season (July and August/ September) showed higher recovery at the H1260 site compared to the climate change sites. During the final sampling in early summer (June 2018), 15N recovery was lower (p > 0.05) at the L600 site compared to H1260 and M860.

During the first sampling in late spring / early summer (May 2017) of extensively managed mesocosms, M860 showed lower recovery in the AGB, contrary to the second sampling of 2017 where M860 showed significantly higher 15N recovery in cumulative AGB than H1260 and L600. During the last sampling of the experiment in summer (June 2018), recovery in cumulative AGB was highest at M860 and lowest at H1260, with L600 being in between and not differing significantly from both H1260 and L600.

Recovery in BGB at the summer sampling 2017 at all sites was higher in the extensive than the intensive treatment. However, in contrast to AGB, this trend was also observable for the 2018 sampling, with significantly higher recovery in BGB for the M860 and L600 sites in the extensive treatment.

For intensive land use, fertilizer N recovery in BGB was not significantly different between climate treatments throughout the whole measurement period. In the extensively managed mesocosms however, single samplings did reveal several differences between climates. The recovery in fertilizer 15N in BGB showed a similar trend as AGB. During the first sampling 2017, all three sites showed the same level of recovery, while this changes during the second and third sampling, where moderate climate change treatment revealed higher recovery rates than the two other sites.

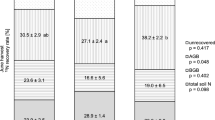

15N recovery in unextractable soil N

Out of all pools, unextractable soil N showed the highest recovery rates ranging between 11.0 and 64.0% with an average fertilizer 15N recovery of 26.9%. Six weeks after first 15N fertilizer application, ca. 25 to 33% of 15N was recovered in this presumably relative stable N pool. Under current climate conditions at H1260, there was significantly higher mean 15N recovery in soil TN in intensive management compared to extensive management. However, with experimentally simulated climate change, mean 15N recovery in soil TN significantly decreased under intensive management while it significantly increased with climate change in extensive management (Fig. 3).

Average recovery of applied 15N fertilizer for both management treatments (left: intensive; right: extensive) and the climate treatments within the respective management. Error bars represent SE of the mean. Legend: DON: dissolved organic nitrogen; BGB: belowground biomass; MBN: microbial biomass nitrogen; AGB: aboveground biomass

15N recovery in microbial biomass N

Ranging between 0.5 to 12.3% with an average of 3.5%, the recovery of 15N tracer from slurry application in soil microbial biomass was of similar magnitude as recovery in BGB. Management had only minor effects on the recovery of 15N in MBN with the only difference occurring at L600, where average recovery was higher in the extensive treatment compared to the intensive treatment.

Experimentally simulated climate change however significantly decreased mean 15N recovery in microbial biomass under intensive management. The same effect was observed for the extensive management treatment mainly during the first sampling with about four times lower 15N recovery in microbial biomass in the climate change treatments.

15N recovery in dissolved mineral and organic nitrogen

On average less than 1% of the 15N tracer was recovered in dissolved mineral and organic N compounds (DON: 0.4%, NH4+: 0.3, NO3−: 0%; Supplementary Table 3). Thus, these pools, characterized by rapid turnover and short mean residence time, played a very minor role for 15N recovery. Recovery of 15N in DON in 2018 was almost one order of magnitude larger than in 2017.

Average 15N recovery in NH4+ and NO3− was not affected by experimentally simulated climate change. However, under intense climate change treatment more 15N was recovered in DON under extensive management compared to intensive management.

Total 15N recovery

Total 15N recovery was between 28.3 and 62.6% (Supplementary Table 3) with an average recovery of 43.3% inferring, that about half of applied 15N remained unrecovered (Fig. 4).

Under intensive management, average recovery of applied fertilizer 15N significantly decreased with increased warming. In contrast, under extensive management, average 15N recovery increased with warming (Supplementary Table 3).

For the average total 15N recovery, management had a significant effect only at H1260 with higher recovery in the intensively managed mesocosms.

Origin of N taken up by plants

Less than 10% of N in the harvested aboveground biomass originated from fertilizer (4.5–8.2%) with the remainder mainly deriving from mineralized N from SOM (Table 6). The contribution of fertilizer N was higher in intensive treatment compared to the extensive treatment. However, under intensive management, the contribution of fertilizer-N to plant N nutrition decreased with warming (Table 6).

N balance

The N balance of the investigated ecosystem was negative in all combinations of climate and management treatments (Fig. 4), indicating a net N loss to the environment. Overall we calculated the lowest losses of 32 ± 16 kg N ha−1 yr−1 for the extensive management under current climate conditions, while net N losses significantly increased under moderate climate change to 124 ± 26 kg N ha−1 yr−1 and decreased under further intense climate change to 75 ± 27 kg N ha−1 yr−1. Under intensive management, net N losses were generally larger than under extensive management, amounting to 93 ± 35 kg N ha−1 yr−1 e.g. for current climate conditions. Under moderate climate change, calculated net N losses increased to as much as 239 ± 48 kg N ha−1 yr−1, which – following the same pattern as observed under extensive management - again slightly decreased under more intense climate change to 210 ± 33 kg N ha−1 yr−1. Generally, the overall N balance values across treatments followed the same dynamics as observed for N exports via plant biomass harvests (n = 6, R2 = 0.986, p < 0.01).

Discussion

Nitrogen pools and flows in montane grassland ecosystems

In comparison to the already high Bavarian average of 33.9 mg g−1 SOC and 3.5 mg g−1 TN in the A horizon of grassland soils (Wiesmeier et al. 2013), the here investigated soil showed even higher SOC and TN concentrations (150 mg g−1 and 16 mg g−1, respectively). Even at up to several fold lower SOC and TN concentrations compared to those of this study, temperate grasslands were shown to be productive systems with yields of 5.5 to 14.5 t ha−1 yr−1 (Ammann et al. 2007; Hoekstra et al. 2010; Nüsse et al. 2018). Interestingly, in our study biomass yield rather than plant N concentration was the dominating control for N-export. This suggests no N limitation of plant growth even in the absence of intensive fertilization, which is also confirmed by similar N concentrations between extensive and intensive treatments (Table 3). This finding is contrary to the negative correlation between yield and N concentration reported for a temperate, fertilized grassland (Zanetti et al. 1997), which had five times lower N stocks compared to the grassland investigated in this study (van Kessel et al. 2006).

Surprisingly, the very high productivity is not due to efficient N fertilizer use in the investigated ecosystem. Tracing N flows revealed SON as the dominant source for plant N uptake, while fertilizer N is only used to very little extent in the year of fertilizer application (Table 6). The 15N fertilizer recovery found in maize crops ranges from 57 to 70% of the applied 15N slurry fertilizer (Paul and Beauchamp 1995), a much higher rate than found in this study. This illustrates a different fate and function of fertilizer-N in montane grasslands, one that does not directly facilitate plant N nutrition.

The higher 15N recovery in unextractable soil N than that in plant pools in this study suggests heterotrophic free living soil microbes as efficient N competitors, coming at the expense of plant uptake (Inselsbacher et al. 2010; Kuzyakov and Xu 2013). Microbial uptake of dissolved organic - and inorganic N seems ubiquitous as no inorganic N accumulation (Fig. 3) was observed despite very high gross N mineralization and fertilization rates. Furthermore, no significant 15N recovery in dissolved mineral N was observed in this study, and overall very low rates of nitrate leaching (1–5 kg N ha−1 yr−1) were reported earlier for similar soils (Fu et al. 2017) and also in this study (Table 1). Low leaching rates are due to high plant N demand, which even exceeds fertilizer input as well as due to the high soil filter capacity that originates from high microbial immobilization of available mineral N. The fast and complete heterotrophic microbial immobilization might be facilitated by the extremely high C content of these soils (Butterbach-Bahl and Dannenmann 2012), enabling effective N retention. Nitrogen assimilated into microbial biomass is likely to undergo stabilization in SOM through adsorption of microbial residues (Bimüller et al. 2014; Miltner et al. 2012). Such a connection between microbial uptake and stabilization of N is confirmed by the 15N recovery patterns in microbial biomass and unextractable, presumably stable, soil N in this study. Consequently, the N supplied by fertilizer is not acting as a direct nutrient supply to support plant growth, but rather serves to refuel SON, a function that is, however, limited by high fertilizer N losses in the range of 50%. The time until stabilized SON is re-mineralized to again enter plant-microbe competition pathways remains to be investigated.

Plants ultimately rely on depolymerization and mineralization of SON to meet their N demand (Schimel and Bennett 2004). In contrast to surface-applied slurry fertilizer N, mineralized N in the rhizosphere appears to be much better accessible for plants. This might explain the dominant SON-based nitrogen nutrition in such grassland soils. Our study also shows that gross mineralization rates are by far sufficient to meet the very high plant N demand of up to 100 kg N ha−1 as observed for single harvests. Sufficient plant unavailable SON is liberated into plant-available mineral N within a time span of 1–2 weeks, even when only the top 5 cm of soil are considered. This would be even increased by several fold when mineralization would be calculated for the entire Ah horizon. Consequently, it can be speculated that there is sufficient mineral N supply so that plants preferably take up mineral N (Hodge et al. 2000). On the other hand, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AM) in such soils can also facilitate organic N nutrition of plants (Hodge et al. 2000; Schimel and Chapin III 1996), however the quantitative contribution of AM to plant N uptake remains unclear (Miransari 2011).

With 47–64% of 15N remaining unrecovered, the dominant fate of slurry-N was loss to the environment. This is in line with the 15N tracing studies by Hoekstra et al. (2010) who found a loss of 24–62% of 15N applied as 15N ammonium-sulfate in slurry in a permanent grass sward in Ireland and by Christian et al. (1997) who found that 40% of applied 15N-Ammonium nitrate was left unrecovered in plant-soil mesocosms planted with Miscantus. The recovery based estimates of 50% slurry N losses are also in good agreement with numbers presented by Zistl-Schlingmann et al. (2019) where total gaseous N emissions (NH3, NO, N2O, N2) from grassland mesocosms of the M860 site measured after slurry application were in the range of 40–50% of the applied slurry-N.

In sum, the fertilizer N fluxes are characterized by very high losses, very inefficient direct plant uptake of fertilizer N but high microbial immobilization, which leads to stabilization of N in SOM. Plants largely rely on N supply based on SON mineralization. Consequently the function of slurry-N is not direct plant N nutrition, but mainly a refueling of the SON stocks, which is however, limited by high N losses.

Nitrogen balance

The refueling of SON stocks by slurry addition is not sufficient to maintain soil N stocks, as clearly shown by the negative N balance at all sites and treatments (Fig. 4). This is a clear indication that current management practices with liquid slurry surface application cannot sustain soil N stocks, especially with progressing climate change as shown by increasing gaps in the N balance (Fig. 4). This is on the one hand caused by the very high production and associated N export via plant harvest. On the other hand, poor plant fertilizer N use efficiency and high loss of applied slurry-N further enhance this problem. The N balance is however accompanied by uncertainty, since the organic N in slurry, except urea, was not 15N labeled so that its fate is not traced in this study. However, as organic slurry-N other than urea also requires mineralization, the partitioning of organic N to plant and microbial uptake or loss might follow comparable patterns as revealed by 15N tracing of ammonium and urea from slurry, but occur with delay. Further uncertainty might originate from overestimation of slurry-N losses because the soil depth of 15–25 cm was not considered. However, in a similar 15N slurry labeling experiment with the soil of the M860 site, 15N recovery in >15 cm depth was more than five times smaller than 15N recovery in 0–15 cm soil depth (Zistl-Schlingmann et al. 2020). Using topsoil recovery of the current study, this translates into a possible overestimation of unrecovered 15N of up to 5% of 15N excess addition. A rather low N translocation in the soil profile is also confirmed by the minimal N leaching rates. Uncertainty is furthermore associated with estimates of biological N fixation which however might be with ca. 15 kg N ha−1 yr−1 a comparably low flux in the grassland N balance.

With a maximum addition of 176 kg N ha−1 during 2017 in the intensive treatment, the fertilization regime carried out in this experiment was in accordance with the national fertilizer ordinance of Germany, which limits the annual fertilizer application to 170 kg N ha−1. However, our results show, that this amount of fertilization cannot sustain the N balance of the investigated grassland system. These findings underline the importance of a reduction of gaseous N loss from fertilizer, not only with regard to mitigation of N gas emissions and associated problems of N deposition (NH3) and atmospheric GHG concentration increase (N2O), but also to mitigate soil N mining. A potential soil N mining of >100 kg N ha−1 yr−1 as revealed in this study is able to significantly reduce the SON stocks of ca. 25 t ha−1 at decadal timescales. On the long-term, this might negatively impact grassland productivity provided that no grassland management with improved N use efficiency is implemented. Moreover, assuming that soil N mining is associated with a concurrent decrease of SOC, significant CO2 emissions from these grassland soils should be expected along with a deterioration of SOM-related soil functions in the long-term.

Effects of management

Intensification of land-use management, i.e., more than a doubling of the number of the fertilization and cutting events, increased growing season / annual productivity by 69–122%. The low contribution of fertilizer N to plant N nutrition (Table 6) suggests that increased N fertilization might not be the crucial direct factor for the increased production, since SOM mineralization seems to be the main N source pool for the plants. Rather, the number of cutting events might be a decisive factor regulating plant productivity (Bernhardt-Römermann et al. 2011; Walter et al. 2012).

In accordance with several studies (Reynolds and D'antonio 1996; Rose and Leuschner 2012; Schippers et al. 1999), management intensity had little to no effect on root biomass, however intensive management decreased the root: shoot ratio due to increased AGB production. As N supply by microbial mineralization, independent of fertilization intensity, was the predominant N source, there may have been little incentive for plants to increase allocation of resources to belowground foraging when fertilization was lower i.e., in the extensive treatments. The increase in AGB 15N recovery under the intensive treatment might be on the one hand related to altered timing and frequency of fertilization, but could also be mediated by changes in plant biodiversity (Hautier et al. 2015), which however remained unmeasured here.

Despite the slight increase in 15N recovery under the intensive treatment, high loss of applied slurry-N and increased plant-N export lead to a further deterioration of the N balance. With every fertilizing/cutting event, the N imbalances increased so that intensive management did not decrease but rather increased annual soil N mining. These findings are in contrast to the study of Ammann et al. (2009), conducted in a temperate grassland with low soil SOC and TN concentrations (Oensingen, Switzerland). These authors reported a net C and N sequestration under intensive management, while extensive management led to a net loss of both. However, Soussana and Lemaire (2014) reported a decline in C sequestration at high stocking densities in grazed grasslands.

In sum, we show that an intensification of management based on slurry surface application is, in contrast to our hypothesis, not suitable to maintain the SON pool of the extremely C- and N-rich soil typical for montane grasslands. In contrast, intensified slurry management increases soil N mining, which might on the long-term negatively influence grassland productivity.

Effects of climate change

The most striking effects of simulated climate change in this study were the increased plant biomass production going along with increased deficits in the N balance, while the generally low fertilizer N use efficiency was only marginally affected. Earlier studies showed variable effects of warming on plant growth and yields. While Sebastià et al. (2008) and Berauer et al. (2019) found stimulating effects of warming on plant growth in subalpine and montane grasslands with C and N-rich soils and cool-moist climate, results in various other studies are diverging. Izaurralde et al. (2011) in a review on North American pastures and Dukes et al. (2005) in a Mediterranean grassland in California did not find effects of warming. In contrast, Egli et al. (2004) have shown decreasing plant growth with warming in alpine /subalpine grasslands in Switzerland. Furthermore, the results of Cantarel et al. (2013) obtained for a perennial grassland in central France and Winkler et al. (2016) for an alpine grassland ecosystem in the Rocky Mountains indicate a high dependency of plant growth on soil water availability rather than warming. Here we show an increase in production at the climate change treatments due to translocation from H1260 to M860. However, compared to this moderate climate change simulation (+1 °C), production after the translocation from H1260 to L600, i.e., the stronger warming treatment (+3 °C), decreased to values that were between control and moderate climate change (Table 4). These findings indicate, concordant to above mentioned studies (Berauer et al. 2019; Cantarel et al. 2013; Egli et al. 2004; Sebastià et al. 2008) that warming had a positive effect on production, while this effect was probably counteracted by lower soil moisture that limited production at the L600 site (see Berauer et al. 2019).

Warming has been shown to increase microbial activity (Rustad et al. 2001; Wang et al. 2016) and decomposition (García-Palacios et al. 2013), thus increasing nutrient availability, decreasing belowground competition for nutrients (Kuzyakov and Xu 2013) and shifting it to other limiting sources like light (Hautier et al. 2009). Together with released temperature limitations for plant growth, this increase in nutrient availability can stimulate productivity unless mineralization of SOM is hampered by decreased water availability (Beier et al. 2008; Borken and Matzner 2009). In our study however we did not find significant changes of gross N mineralization in the climate change treatments. Consequently, instead of changing N availability, it might be rather increases in the length of the growing season that regulated increases in biomass production until decreasing soil moisture became limiting due to plant physiological constraints (Berauer et al. 2019; Cantarel et al. 2013).

Because 15N recovery in soil and plant N pools were only marginally affected by the climate change treatments, the effects of climate change on production and associated N exports were dominating the changes of the N balance. Simulated climate change increased the missing N needed to close the grassland N balance from 25 kg N ha−1 (control) which we consider to be hardly significant in view of possible slight overestimation of losses and general uncertainty of the N mass balance calculations, to 117 and 67 kg N ha−1 year in extensive treatments. This effect was even more pronounced in the intensive treatment with increases from 88 (control) to 236 and 206 in the moderate and intense climate change treatments, respectively. Negative N balances in this order of magnitude have the potential to significantly reduce SON stocks of currently ca 25 t N ha−1 within time spans of decades. These findings are asking for climate-adapted management, i.e., fertilizer with improved N use efficiency and reduced losses. This could be the traditional historical management with solid stall manure mixed with straw, containing a higher proportion of organic N (LfL 2009). Furthermore, injection or acidification of liquid slurry could also reduce N losses (Fangueiro et al. 2017; Stevens et al. 1989), however tradeoffs with increased N2O emissions would need to be quantified.

Conclusion

The N cycle of montane and subalpine grasslands with very C- and N-rich soils is characterized by enormous productivity of plant biomass both in extensive and intensive treatments. The very high plant N demand is largely supported by mineralization of SOM but to a much lower extend directly by fertilizer-N which is used with very low efficiency and thus results in substantial gaseous N losses. All of this results in soil N mining that is increasing under climate change conditions. In the long term, intensification of formerly extensively managed grasslands might even enhance N mining, thus depleting SON stocks and associated soil functions such as biomass production and likely SOC stocks as well. Consequently, in order to maintain SON stocks and long-term productivity, a management of montane and subalpine soils with their extremely high SOC and TN content based on frequent harvest and liquid slurry application is not recommended.

References

Ammann C, Flechard CR, Leifeld J, Neftel A, Fuhrer J (2007) The carbon budget of newly established temperate grassland depends on management intensity. Agric Ecosyst Environ 121:5–20

Ammann C, Spirig C, Leifeld J, Neftel A (2009) Assessment of the nitrogen and carbon budget of two managed temperate grassland fields. Agric Ecosyst Environ 133:150–162

Bardgett RD, Streeter TC, Bol R (2003) Soil microbes compete effectively with plants for organic-nitrogen inputs to temperate grasslands. Ecology 84(5):1277–1287

Beier C, Emmett BA, Peñuelas J, Schmidt IK, Tietema A, Estiarte M, Gundersen P, Llorens L, Riis-Nielsen T, Sowerby A (2008) Carbon and nitrogen cycles in European ecosystems respond differently to global warming. Sci Total Environ 407:692–697

Berauer BJ, Wilfahrt PA, Arfin-Khan MAS, Eibes P, von Heßberg A, Ingrisch J, Schloter M, Schuchardt MA, Jentsch A (2019) Low resistance of montane and alpine grasslands to abrupt changes in temperature and precipitation regimes. Arct Antarct Alp Res 51:215–231

Bernhardt-Römermann M, Römermann C, Sperlich S, Schmidt W (2011) Explaining grassland biomass–the contribution of climate, species and functional diversity depends on fertilization and mowing frequency. J Appl Ecol 48:1088–1097

Bidartondo MI, Burghardt B, Gebauer G, Bruns TD, Read DJ (2004) Changing partners in the dark: isotopic and molecular evidence of ectomycorrhizal liaisons between forest orchids and trees. Proc Royal Soc London Series B: Biol Sci 271:1799–1806

Bimüller C, Dannenmann M, Tejedor J, von Lützow M, Buegger F, Meier R, Haug S, Schroll R, Kögel-Knabner I (2014) Prolonged summer droughts retard soil N processing and stabilization in organo-mineral fractions. Soil Biol Biochem 68:241–251

Blum WEH (2005) Functions of soil for society and the environment. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 4:75–79

BMLEV (2012) Statistisches Jahrbuch über Ernährung, Landwirtschaft und Forsten der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 2012. Landwirtschaftsverlag GmbH Münster-Hiltrup, 606

Borken W, Matzner E (2009) Reappraisal of drying and wetting effects on C and N mineralization and fluxes in soils. Glob Chang Biol 15:808–824

Butterbach-Bahl K, Dannenmann M (2012) Soil carbon and nitrogen interactions and biosphere-atmosphere exchange of nitrous oxide and methane, Recarbonization of the Biosphere. Springer, pp 429–443

Cantarel AAM, Bloor JMG, Deltroy N, Soussana J-F (2011) Effects of climate change drivers on nitrous oxide fluxes in an upland temperate grassland. Ecosystems 14:223–233

Cantarel AAM, Bloor JMG, Soussana J-F (2013) Four years of simulated climate change reduces above-ground productivity and alters functional diversity in a grassland ecosystem. J Veg Sci 24:113–126

Cardenas LM, Bhogal A, Chadwick MGK, Misselbrook T, Rees RM, Thorman RE, Watson CJ, Williams JR, Smith KA (2019) Nitrogen use efficiency and nitrous oxide emissions from five UK fertilised grasslands. Sci Total Environ 661:696–710

Christian DG, Poulton PR, Riche AB, Yates NE (1997) The recovery of 15N-labelled fertilizer applied to Miscanthus× giganteus. Biomass Bioenergy 12:21–24

Dannenmann M, Bimüller C, Gschwendtner S, Leberecht M, Tejedor J, Bilela S, Gasche R, Hanewinkel M, Baltensweiler A, Kögel-Knabner I (2016) Climate change impairs nitrogen cycling in European beech forests. PLoS One 11:e0158823

de Vries FT, Bloem J, Quirk H, Stevens CJ, Bol R, Bardgett RD (2012) Extensive management promotes plant and microbial nitrogen retention in temperate grassland. PLoS One 7:e51201

Dukes JS, Chiariello NR, Cleland EE, Moore LA, Shaw MR, Thayer S, Tobeck T, Mooney HA, Field CB (2005) Responses of grassland production to single and multiple global environmental changes. PLoS Biol 3:e319

Egli M, Hitz C, Fitze P, Mirabella A (2004) Experimental determination of climate-change effects on above-ground and below-ground organic matter in alpine grasslands by translocation of soil cores. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 167:457–470

Fangueiro D, Pereira JLS, Macedo S, Trindade H, Vasconcelos E, Coutinho J (2017) Surface application of acidified cattle slurry compared to slurry injection: impact on NH3, N2O, CO2 and CH4 emissions and crop uptake. Geoderma 306:160–166

Fraser LH, Pither J, Jentsch A, Sternberg M, Zobel M, Askarizadeh D, Bartha S, Beierkuhnlein C, Bennett JA, Bittel A (2015) Worldwide evidence of a unimodal relationship between productivity and plant species richness. Science 349:302–305

Fu J, Gasche R, Wang N, Lu H, Butterbach-Bahl K, Kiese R (2017) Impacts of climate and management on water balance and nitrogen leaching from montane grassland soils of S-Germany. Environ Pollut 229:119–131

Fu J, Gasche R, Wang N, Lu H, Butterbach-Bahl K, Kiese R (2019) Dissolved organic carbon leaching from montane grasslands under contrasting climate, soil and management conditions. Biogeochemistry 145(1–2):47–61

García-Palacios P, Maestre FT, Kattge J, Wall DH (2013) Climate and litter quality differently modulate the effects of soil fauna on litter decomposition across biomes. Ecol Lett 16:1045–1053

Gobiet A, Kotlarski S, Beniston M, Heinrich G, Rajczak J, Stoffel M (2014) 21st century climate change in the European Alps—a review. Sci Total Environ 493:1138–1151

Guo C, Simon J, Gasche R, Naumann PS, Bimüller C, Pena R, Polle A, Kögel-Knabner I, Zeller B, Rennenberg H (2013) Minor contribution of leaf litter to N nutrition of beech (Fagus sylvatica) seedlings in a mountainous beech forest of southern Germany. Plant Soil 369:657–668

Harrison KA, Bol R, Bardgett RD (2007) Preferences for different nitrogen forms by coexisting plant species and soil microbes. Ecology 88(4):989–999

Harrison KA, Bol R, Bardgett RD (2008) Do plant species with different growth strategies vary in their ability to compete with soil microbes for chemical forms of nitrogen? Soil Biol Biochem 40(1):228–237

Hart SC, Firestone MK, Paul EA, Smith JL (1993) Flow and fate of soil nitrogen in an annual grassland and a young mixed-conifer forest. Soil Biol Biochem 25(4):431–442

Hautier Y, Niklaus PA, Hector A (2009) Competition for light causes plant biodiversity loss after eutrophication. Science 324:636–638

Hautier Y, Tilman D, Isbell F, Seabloom EW, Borer ET, Reich PB (2015) Anthropogenic environmental changes affect ecosystem stability via biodiversity. Science 348:336–340

Hodge A, Robinson D, Fitter A (2000) Are microorganisms more effective than plants at competing for nitrogen? Trends Plant Sci 5:304–308

Hoekstra NJ, Lalor STJ, Richards KG, O’Hea N, Lanigan GJ, Dyckmans J, Schulte RPO, Schmidt O (2010) Slurry 15 NH 4-N recovery in herbage and soil: effects of application method and timing. Plant Soil 330:357–368

Inselsbacher E, Umana NHN, Stange FC, Gorfer M, Schüller E, Ripka K, Zechmeister-Boltenstern S, Hood-Novotny R, Strauss J, Wanek W (2010) Short-term competition between crop plants and soil microbes for inorganic N fertilizer. Soil Biol Biochem 42:360–372

IUSS Working Group WRB (2015) World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2014, update 2015 International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps. World Soil Resources Reports, FAO No. 106

Izaurralde RC, Thomson AM, Morgan JA, Fay PA, Polley HW, Hatfield JL (2011) Climate impacts on agriculture: implications for forage and rangeland production. Agron J 103:371–381

Jacot KA, Lüscher A, Nösberger J, Hartwig UA (2000) The relative contribution of symbiotic N2 fixation and other nitrogen sources to grassland ecosystems along an altitudinal gradient in the Alps. Plant Soil 225:201–211

Jensen LS, Pedersen IS, Hansen TB, Nielsen NE (2000) Turnover and fate of 15N-labelled cattle slurry ammonium-N applied in the autumn to winter wheat. Eur J Agron 12:23–35

Kiese R, Fersch B, Baessler C, Brosy C, Butterbach-Bahl K, Chwala C, Dannenmann M, Fu J, Gasche R, Grote R, Jahn C (2018) The TERENO pre-Alpine observatory: integrating meteorological, hydrological, and biogeochemical measurements and modeling. Vadose Zone J 17(1)

Kühnel A, Garcia-Franco N, Wiesmeier M, Burmeister J, Hobley E, Kiese R, Dannenmann M, Kögel-Knabner I (2019) Controlling factors of carbon dynamics in grassland soils of Bavaria between 1989 and 2016. Agric Ecosyst Environ 280:118–128

Kuzyakov Y, Xu X (2013) Competition between roots and microorganisms for nitrogen. Mechanisms and ecological relevance. New Phytol 198:656–669

LfL (2009) Wirtschaftsdünger und Gewässerschutz Lagerung und Ausbringung von Wirtschaftsdüngern in der Landwirtschaft. Bayerische Landesanstalt für Landwirtschaft, Germany. https://www.lfl.bayern.de/mam/cms07/publikationen/daten/informationen/p_34348.pdf Accessed Dec 16 2019

LfU (2011) Ergebnisse der Stickstoff-Deposition aus dem Niederschlagsmessnetz des LfU (Teil Immissionsökologie) imVergleich mit UBA-Modelldaten zur Stickstoff-Vorbelastung. Bayerisches Landesamt für Umwelt (LfU). https://www.lfu.bayern.de/luft/schadstoffe_luft/ eutrophierung versauerung/uba_daten/doc/infoblatt_16_n_depo_lfu_uba.pdf. Accessed March 25 2020

Miltner A, Bombach P, Schmidt-Brücken B, Kästner M (2012) SOM genesis: microbial biomass as a significant source. Biogeochemistry 111:41–55

Miransari M (2011) Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and nitrogen uptake. Arch Microbiol 193:77–81

Muñoz GR, Kelling KA, Powell JM, Speth PE (2004) Comparison of estimates of first-year dairy manure nitrogen availability or recovery using nitrogen-15 and other techniques. J Environ Qual 33:719–727

Nüsse A, Linsler D, Loges R, Reinsch T, Taube F, Ludwig B (2018) Effect of grassland harvesting frequency and N-fertilization on stocks and dynamics of soil organic matter in the temperate climate. Arch Agron Soil Sci 64:1925–1931

Paul JW, Beauchamp EG (1995) Availability of manure slurry ammonium for corn using 15N-labelled (NH4) 2SO4. Can J Soil Sci 75:35–42

Pepin N, Bradley RS, Diaz HF, Baraër M, Caceres EB, Forsythe N, Fowler H, Greenwood G, Hashmi MZ, Liu XD (2015) Elevation-dependent warming in mountain regions of the world. Nat Clim Chang 5:424

Pohl S, Garvelmann J, Wawerla J, Weiler M (2014) Potential of a low-cost sensor network to understand the spatial and temporal dynamics of a mountain snow cover. Water Resour Res 50(3):2533–2550

Rabot E, Wiesmeier M, Schlüter S, Vogel H-J (2018) Soil structure as an indicator of soil functions: a review. Geoderma 314:122–137

Reynolds HL, D'antonio C (1996) The ecological significance of plasticity in root weight ratio in response to nitrogen: opinion. Plant Soil 185:75–97

Rocha KF, Mariano E, Grassmann CS, Trivelin PCO, Rosolem CA (2019) Fate of 15N fertilizer applied to maize in rotation with tropical forage grasses. Field Crop Res 238:35–44

Rose L, Leuschner C (2012) The diversity–productivity relationship in a permanent temperate grassland: negative diversity effect, dominant influence of management regime. Plant Ecol Divers 5:265–274

Rowlings DW, Scheer C, Liu S, Grace PR (2016) Annual nitrogen dynamics and urea fertilizer recoveries from a dairy pasture using 15N; effect of nitrification inhibitor DMPP and reduced application rates. Agric Ecosyst Environ 216:216–225

Rustad L, Campbell J, Marion G, Norby R, Mitchell M, Hartley A, Cornelissen J, Gurevitch J (2001) A meta-analysis of the response of soil respiration, net nitrogen mineralization, and aboveground plant growth to experimental ecosystem warming. Oecologia 126:543–562

Scheiner JD, Gutiérrez-Boem FH, Lavado RS (2002) Sunflower nitrogen requirement and 15N fertilizer recovery in Western Pampas, Argentina. Eur J Agron 17:73–79

Schimel JP, Bennett J (2004) Nitrogen mineralization: challenges of a changing paradigm. Ecology 85:591–602

Schimel JP, Chapin FS III (1996) Tundra plant uptake of amino acid and NH4+ nitrogen in situ: plants complete well for amino acid N. Ecology 77:2142–2147

Schippers P, Snoeijing I, Kropff MJ (1999) Competition under high and low nutrient levels among three grassland species occupying different positions in a successional sequence. New Phytol 143:547–559

Sebastià M-T, Kirwan L, Connolly J (2008) Strong shifts in plant diversity and vegetation composition in grassland shortly after climatic change. J Veg Sci 19:299–306

Smiatek G, Kunstmann H, Knoche R, Marx A (2009) Precipitation and temperature statistics in high-resolution regional climate models: evaluation for the European Alps. J Geophys Res-Atmos 114

Soussana JF, Lemaire G (2014) Coupling carbon and nitrogen cycles for environmentally sustainable intensification of grasslands and crop-livestock systems. Agric Ecosyst Environ 190:9–17

Stevens RJ, Laughlin RJ, Frost JP (1989) Effect of acidification with sulphuric acid on the volatilization of ammonia from cow and pig slurries. J Agric Sci 113:389–395

van Kessel C, Boots B, De Graaff MA, Harris D, Blum H, Six J (2006) Total soil C and N sequestration in a grassland following 10 years of free air CO2 enrichment. Glob Chang Biol 12(11):2187–2199

Wagner S, Berg P, Schädler G, Kunstmann H (2013) High resolution regional climate model simulations for Germany: part II—projected climate changes. Clim Dyn 40:415–427

Walter J, Grant K, Beierkuhnlein C, Kreyling J, Weber M, Jentsch A (2012) Increased rainfall variability reduces biomass and forage quality of temperate grassland largely independent of mowing frequency. Agric Ecosyst Environ 148:1–10

Wang C, Chen Z, Unteregelsbacher S, Lu H, Gschwendtner S, Gasche R, Kolar A, Schloter M, Kiese R, Butterbach-Bahl K (2016) Climate change amplifies gross nitrogen turnover in montane grasslands of Central Europe in both summer and winter seasons. Glob Chang Biol 22:2963–2978

Warscher M, Wagner S, Marke T, Laux P, Smiatek G, Strasser U, Kunstmann H (2019) A 5 km resolution regional climate simulation for central europe: performance in high mountain areas and seasonal, regional and elevation-dependent variations. Atmosphere 10:682

Wiesmeier M, Hübner R, Barthold F, Spörlein P, Geuß U, Hangen E, Reischl A, Schilling B, von Lützow M, Kögel-Knabner I (2013) Amount, distribution and driving factors of soil organic carbon and nitrogen in cropland and grassland soils of Southeast Germany (Bavaria). Agric Ecosyst Environ 176:39–52

Wilson JB, Peet RK, Dengler J, Pärtel M (2012) Plant species richness: the world records. J Veg Sci 23:796–802

Winkler DE, Chapin KJ, Kueppers LM (2016) Soil moisture mediates alpine life form and community productivity responses to warming. Ecology 97:1553–1563

Wolf B, Zheng X, Brüggemann N, Chen W, Dannenmann M, Han X, Sutton MA, Wu H, Yao Z, Butterbach-Bahl K (2010) Grazing-induced reduction of natural nitrous oxide release from continental steppe. Nature 464:881–884

Xu X, Ouyang H, Richter A, Wanek W, Cao G, Kuzyakov Y (2011) Spatio-temporal variations determine plant–microbe competition for inorganic nitrogen in an alpine meadow. J Ecol 99(2):563–571

Zanetti S, Hartwig UA, van Kessel C, Lüscher A, Hebeisen T, Frehner M, Fischer BU, Hendrey GR, Blum H, Nösberger J (1997) Does nitrogen nutrition restrict the CO2 response of fertile grassland lacking legumes? Oecologia 112:17–25

Zhou M, Zhu B, Brüggemann N, Dannenmann M, Wang Y, Butterbach-Bahl K (2016) Sustaining crop productivity while reducing environmental nitrogen losses in the subtropical wheat-maize cropping systems: a comprehensive case study of nitrogen cycling and balance. Agric Ecosyst Environ 231:1–14

Zistl-Schlingmann M, Feng J, Kiese R, Stephan R, Zuazo P, Willibald G, Wang C, Butterbach-Bahl K, Dannenmann M (2019) Dinitrogen emissions: an overlooked key component of the N balance of montane grasslands. Biogeochemistry 143:15–30

Zistl-Schlingmann M, Kwatcho Kengdo S, Kiese R, Dannenmann M (2020) Management intensity controls nitrogen-use-efficiency and flows in grasslands- a 15N tracing experiment. Agronomy 10(4):606

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the BayCEER – Laboratories for Isotope and Biogeochemistry in Bayreuth for the quick and impeccable analysis of plant samples. Furthermore, we thank Anne Schucknecht for help with graphical illustration.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL. This work was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) in the SUSALPS project (Sustainable use of alpine and prealpine grassland soils in a changing climate, FKZ 031B0516A), embedded within the BonaRes initiative. Further funding was obtained from the Helmholtz TERENO (Terrestrial Environmental Observatories) initiative.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Martin Weih.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 57.2 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schlingmann, M., Tobler, U., Berauer, B. et al. Intensive slurry management and climate change promote nitrogen mining from organic matter-rich montane grassland soils. Plant Soil 456, 81–98 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-020-04697-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-020-04697-9