Abstract

Background

Recycling the ever-increasing plastic waste has become an urgent global concern. One of the most convenient methods for plastic recycling is pyrolysis, owing to its environmentally friendly nature and its intrinsic properties. Understanding the pyrolysis process and the degradation mechanism is crucial for scale-up and reactor design. Therefore, we studied kinetic modelling of the pyrolysis process for one of the most common plastics, polyethylene terephthalate (PET). The focus was to better understand and predict PET pyrolysis when transitioning to a low carbon economy and adhering to environmental and governmental legislation. This work aims at presenting for the first time, the kinetic triplet (activation energy, pre-exponential constant, and reaction rate) for PET pyrolysis using the differential iso-conversional method. This is coupled with the in-situ online tracking of the gaseous emissions using mass spectrometry.

Results

The differential iso-conversional method showed activation energy (Ea) values of 165–195 kJ mol−1, R2 = 0.99659. While the ASTM-E698 method showed 165.6 kJ mol−1 and integral methods such as Flynn-–Wall and Ozawa (FWO) (166–180 kJ mol−1). The in-situ Mass Spectrometry results showed the gaseous pyrolysis emissions, which are C1 hydrocarbons and H–O-C=O along with C2 hydrocarbons, C5–C6 hydrocarbons, acetaldehyde, the fragment of O–CH=CH2, hydrogen, and water.

Conclusions

From the obtained results herein, thermal predictions (isothermal, non-isothermal and step-based heating) were determined based on the kinetic parameters. They can be used at numerous scale with a high level of accuracy compared with the literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Over 9 billion tonnes of plastic have been produced globally since the 1940s, with an annual growth rate of 8.7% [1]. Plastic materials are subdivided into seven different types and fulfil different purposes in our daily life such as in electronics, construction materials, agriculture, household items and packaging films. The widespread use is due to their intrinsic properties, i.e., chemical inertness, mechanical, pressure resistance, durability, versatility, flexibility, and cheap production cost, along with the thermal stability from the additives and stabilisers used in the production phase [2]. Over the last 60 years, consumer plastic use has increased by approximately 20 times, where the annual production had dramatically increased from 15 million tonnes (Mt) in 1964, to 335 Mt in 2016, and is expected to reach 1124 Mt by the year 2050 [3, 4]. The annual consumption of water bottles alone has reached 500 billion units globally [5]. However, the disposal rate of these plastic debris has risen, making a substantial negative impact on the environment as well as public human health. The plastic waste generated in 2015 was 6300 Mt, where only 9% has been recycled, 12% incinerated, and the rest have been sent to landfills (79%) [6]. In the next 5 years, the plastic waste production rate will reach 220 Mt per annum, with its end-of-life destination deemed to be mainly in the sediment, biota, and aquatic ecosystem such as oceans and rivers [micro-plastic (< 5 mm) and nanoplastic (< 1.2 μm)], [7]. Where the complete degradation of its polymers could take centuries. Furthermore, direct burning of those plastic wastes generates hazardous emissions along with chemicals such as phosgene, dioxins, and carbon monoxide that are linked to human cancers and endocrine disruption [8, 9]. However, it is possible to add additional value to this waste through processes such as pyrolysis, solvent dissolution, gasification, and other valorisation approaches while promoting the circular economy [10, 11]. This approach of using a waste stream will complete the full cycle of plastic and, thus, directly support and facilitate the concept of the circular economy.

There are mainly four different technologies in dealing with plastic waste management which are: re-extrusion that requires semi-clean plastic scrap, along with mechanical (physical), chemical (solvolysis and pyrolysis), and energy recovery (incineration) [2, 12, 13]. Lopez et al. found out that the variability and inconsistency of the feed composition was the major challenge along with catalyst deactivation [14,15,16].

The most common polymers studied are polyethylene terephthalate (PET), high-density polyethylene (HDPE), polypropylene (PP), and polystyrene (PS), where the pyrolysis and reforming conditions were around 500 and 700 °C, respectively. Nearly half of the total plastic market globally comes from PE (polyethylene) and PET with a contribution of 40% [17] in various sectors such as agriculture, drinking water bottles, food packaging, and construction materials. Thermoplastics account for 80% of the total plastic consumption [2]. PET (C10H8O4)n) is the most abundant thermoplastic due to its characteristics of existing in different forms such as a one-dimensional fibre, 2D films, and 3D bottles and containers [18, 19]. It is the third-most consumed polymer in Europe after PP and LDPE, and the most widely used plastic in the packaging industry [20,21,22]. The global consumption and demand for PET reached 60 Mt by 2011 and is increasing by 4.5% each year [23]. It has been reported in the literature that PET plastic material has a similar energy content than that of soft coal, with a higher heating value of 46.2 MJ kg−1 and ultimate elemental analysis of > 45 wt.% carbon, 36 wt.% hydrogen, and 18 wt.% oxygen [20, 24, 25]. Most of those PET and plastic waste materials, in general, are non-biodegradable and their end-of-life destination is landfill or incineration. There is also another challenge that faces the recycling of these problematic materials, which is the difficulty of the selective and effective separation of the plastic mixture. For instance, a standard PET bottle contains about 10–15 wt.% PE in the form of printed labels and cups, where their separation is usually difficult [17].

One of the most convenient methods for plastic recycling is pyrolysis owing to its environmentally friendly nature. Furthermore, unlike other recycling processes such as mechanical and chemicals methods, pyrolysis is a flexible process where plastic waste could be treated alongside municipal solid waste such as e-waste, biomass, and others [26]. Interestingly, only 5% of the calorific value of the plastic waste is being used in the endothermic cracking process, which in the case of PET is 214 kJ kg−1 [27]. The pyrolytic products of plastic are oil (22–49 wt.%), gases (18–30 wt.%), and solid char (30–50 wt.%); where different operating parameters could affect the process and product composition (plastic type, residence time, pyrolytic temperature, ramping rate, and reactor type) [27]. As the operating parameters can shift the product composition and alter the reaction pathway, it is important to use kinetic modelling to help describe the reaction mechanism during the thermal cracking of plastic polymers. Ganeshan et al. [28], in their attempt to understand the PET pyrolysis process via kinetic modelling, used Coats–Redfern method that assumes the reaction is first order. They reported activation energies (Ea) value in the range of 133–251 kJ mol−1; however, the value of R2 was low (< 0.8). Thus, they concluded that the Coats–Redfern method is not always suitable for calculating the kinetic parameters. Mishra et al. [29] studied kinetic modelling approaches (Coats–Redfern method, Kissinger–Akahira–Sunose, Flynn–Wall and Ozawa method, Friedman method, and Starink) for the co-pyrolysis of PET with biomass seeds. The KAS method of PET pyrolysis showed variation in the Ea value from 210 to 241 kJ mol−1 within reaction progress α = 0.1–0.8, where the average Ea—was 230.7 kJ mol−1. Under the same conditions, the FWO and Starink methods showed similar variation in the Ea value from 211–241 kJ mol−1 and 211–242 kJ mol−1, respectively, with an Ea average of 230.5 and 231.0 kJ mol−1. The Friedman method showed a slightly lower difference in values under the same conditions with 208.6–236.0 kJ mol−1 and an average Ea—of 225.6 kJ mol−1. They performed the kinetic modelling based on three heating rates of 10, 30, and 50 °C min−1, while for reliable evaluation of the kinetic parameters, it should be at low heating rates of less than 8 °C min−1 (with a ratio between the lowest and the highest heating rate of > 10) with four or five heating rates [30]. Das and Tiwari [18] measured the kinetic parameters for PET pyrolysis at high heating rates of 5, 10, 20, 40, and 50 °C min−1 using the iso-conversional method. They reported Ea values in the range of 196–217 kJ mol−1. Al-asadi and Miskolczi measured the emissions related to the uncatalysed along with Ni/zeolite catalytic pyrolysis of PET but only at a high-temperature range of 600–900 °C [17]. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first detailed study in measuring and evaluating the kinetic triplet (activation energy, pre-exponential constant, and reaction rate) of PET plastic pyrolysis with the use of Advanced Kinetics and Technology Solutions (AKTS) software. This work aims at presenting for the first time, the kinetic triplet (activation energy, pre-exponential constant, and the rate of reaction) for PET pyrolysis using the differential iso-conversional method. This is coupled with the in-situ online tracking of the gaseous emissions using mass spectrometry, as there are a few and limited studies on oxygenated macromolecules such as PET in the literature [20, 22]. The kinetic triplet can benefit in process modelling systems to help better understand the process at scale, as these values are not influenced based on scale. This ultimately aids in reactor optimization and design at scale as it gives a better insight into the reaction mechanism. This can be used by plastic recyclers worldwide and the predictions made here can be used to determine how the rate of reaction changes based on temperature and heating rate beyond experimental results using isothermal, non-isothermal and stepwise heating regimes.

Materials and methods

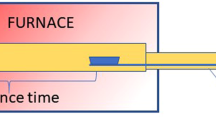

Sample preparation and in-situ gaseous emission detection using mass spectrometry

The PET sample was collected from used water bottles, then washed with deionized water, dried, and finally crushed down into a form of small particles and sieved in the range of less than 100 µm to avoid the mass and heat transfer limitations during the kinetic modelling and pyrolysis tests, as shown in Additional file 1: Figure S1. The PET pyrolysis was performed in a fixed bed reactor, where the output of the reactor is coupled and attached to a mass spectrometer (MS) through a heated quartz capillary tube. To prevent any condensation, dissolution, or adsorption on the tube wall, all the lines were heated to 150 °C, where the evolved gas mixtures were then directly fed to the mass spectrometer. The MS (Hiden Analytical instrument) was performed under vacuum and the rapid in-situ detection of the characteristic fragment ion intensity of the associated gaseous emissions such as hydrocarbons and other related emissions including characteristic ion species according to its mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) such as m/z = 15 (C1 hydrocarbons), m/z = 27 (C2 hydrocarbons), m/z = 42 (C5 hydrocarbons), m/z = 78 (C6 hydrocarbons), m/z = 84 (Krypton), m/z = 43 (acetic acid), m/z = 44 (acetaldehyde or carbon dioxide), m/z = 2 (hydrogen), m/z = 45 (CHO2), m/z = 18 (water), and m/z = 29 (acetaldehyde).

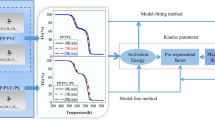

Kinetic modelling of PET waste via AKTS

The evaluation of the kinetic parameters of PET pyrolysis was determined using the TGA data (at different heating rates of 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 °C min−1) under N2 atmosphere with a ratio of 16 between the lowest and the highest heating rate. The heating rate of 4 °C min−1 was repeated for the reproducibility and accuracy of results. The TGA experiments were conducted in a simultaneous thermal analysis Mettler Toledo (TGA/DSC) Thermogravimetric analyser Pyris TGA/DSC1, and changes in the mass of the sample were recorded during the ramping operation.

The TGA instrument was also calibrated for buoyancy effects to allow quantitative estimation of weight changes. Experiments were performed twice to ensure reproducibility and the standard error was found to be ± 1 °C. The ICTAC Kinetics Committee published the problems and reported the essential principals that should be followed to obtain thermal analysis data that are adequate to the kinetic computations [31]. To determine the kinetic parameters more accurately and to better understand the PET pyrolysis, Advanced Kinetics and Technology Solutions (AKTS) software was utilized. AKTS software correlated and validated the practical experiments with theoretical calculations for the kinetic modelling of the pyrolysis process of the PET plastic waste along with calculating the activation energy (Ea) and the pre-exponential factor. Different kinetic modelling methods were employed such as ASTM-E698, Flynn–Wall and Ozawa (FWO), and differential iso-conversional (model-free) method such as the Friedman method. The latter method measures Ea and pre-exponential constant at different extents of reaction progress α without requiring prior knowledge of the reaction mechanism [32]. Consequently, the iso-conversional (differential) method was used herein to measure the kinetic parameters using heating rates ranging from 0.5 to 8 °C min−1 as a function of reaction progress (α). Where the rate of the thermal decomposition of the waste PET plastic can be expressed according to the iso-conversional method as a function of reaction temperature and α, where the latter is calculated from the initial, actual, and final masses of PET waste. The Arrhenius equation defined the temperature-dependent function of the kinetic parameters as shown in Eq. 1:

The non-isothermal iso-conversional method usually utilizes different heating rates, β = dT dt−1, and thus, the PET plastic pyrolysis can be expressed as shown in Eq. 2:

One of the examples of iso-conversional methods (the non-isothermal) such as ASTM-E698 is shown in Eq. 3:

whereas the Flynn–Wall and Ozawa (FWO) method is shown in Eq. 4:

The equation for the Kissinger–Akahira–Sunrose (KAS) methods is shown below in Eq. 5:

Finally, the isothermal iso-conversional method is represented in the Friedman method as shown below in Eq. 6:

Results and discussion

The kinetic modelling results

AKTS thermokinetics package was utilized in this study to facilitate kinetic analysis of PET plastic bottle samples using conventional thermo-analytical data, which, in the case of this study, was in the form of TGA. This can allow for the study of the thermal behaviour of the PET samples within the discrete areas of quality assurance and research and development (R&D). The analysis begins with the importations of ASCII files from the TGA instrument. A derivation filter is then applied to provide the DTG reading of the sample. The DTG signal then has a baseline constructed to integrate the curve and provide the evaluation of the kinetic parameters such as rate of reaction, activation energy and pre-exponential constant (also commonly known in the literature as the kinetic triplet). Herein, baselines were constructed to integrate the DTG results with respect to the PET plastic pyrolysis profile. The type of baseline used herein was horizontal. AKTS has numerous possibilities for advanced baseline construction such as spline, sigmoid, tangential first point, tangential last point, etc. as baseline construction is the most crucial step in kinetic data treatment, and these constructed baselines can be optimized numerically. Additionally, the parameters for the Arrhenius equation can be determined for multi-step complex reactions, which cannot be visually seen if the thermo-analytical curves potentially overlap. Based on the obtained kinetic parameters, simulation curves are generated for the reaction rate and the reaction progress, which were compared with the experimental data to check the accuracy of the modelling. As the PET pyrolysis reaction progresses, there is a change in the specific heat of the reactant–product mixture, thus changing the heat of reaction and, consequently, the kinetic parameters. Specifically, using the AKTS package, the progress/extent of reaction (α) and the reaction rate can be predicted for a wide variety of temperature profiles (non-isothermal, isothermal, modulated, or periodic temperature variations or step base heating).

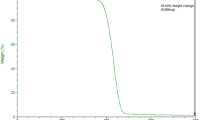

The software ultimately provides a robust and accurate result due to strict thermokinetic criteria of average correlation coefficient R having to be greater than 0.95 and the plotting of high-resolution data over 10,000 specific data points for the parameters and alpha values. Additional file 1: Figure S2 shows the practical results, their integration, and the subsequent simulated results from the TGA kinetic modelling results at different heating rates from 0.5 to 8 °C min−1. Similar TGA results were reported in the literature [22, 27, 33, 34]. The high mass loss in PET pyrolysis is due to the high volatile matter content as reported by Lee et al., who reported a value of 86.1 wt.% [22], Oh et al. was 88.1% [25], while Park et al. stated 91.6% [34] in PET pyrolysis. While the DSC results of two heating rates (0.5 and 1 °C min−1) showed two endothermic peaks, along with a small shoulder of an exothermic peak, as shown in Additional file 1: Figure S3. The first two endothermic peaks at 252 and 460 °C are due to the PET melting and pyrolysis, while the third peak at around 800 °C is characteristic of the graphitization of the residual carbon material. This agrees with the work reported by Kamali et al., where the three peaks appeared at 254, 466, and 791 °C, respectively [5]. It is obvious that there is a good match between the practical and theoretical simulation, as shown in Additional file 1: Figure S2 from the lowest to the highest heating rate with R2 = 0.99659.

There is a clear shift towards a higher decomposition temperature by increasing the heating rate 16 times (from 0.5 to 8 °C min−1), as shown in Table 1 with R2 = 0.99659. For instance, the temperature range for the pyrolysis reaction to occur at 0.5 °C min−1 was 261–442 °C, while at 8 °C min−1, it increased to 328–535 °C. Furthermore, the onset temperature increased from 351 to 413 °C, respectively. By increasing the heating rates by 16 times, the offset temperature increased by 56 °C, as shown in Table 1. Thus, it is not surprising that the peak maximum was shifting towards a higher reaction temperature with increasing the heating rates, as 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 °C min−1 showed peak maximum at 374, 389, 402, 417, and 433 °C, respectively. On the other hand, the time required for the pyrolysis reaction to finish has dramatically decreased by 13 times with increasing the heating rates by 16 times. Table 1 shows that the required time for completion at 0.5 °C min−1 was 49,447 s, while at 8 °C min−1 was 3789 s. Based on the integrated DTG curves from the five heating rates shown in Additional file 1: Figure S2, the average PET plastic weight loss up to 600 °C was 82.898 ± 1.2 wt.% of its initial mass.

To obtain the kinetic parameters, first, the reaction progress (α) was plotted versus the reaction temperature as shown in Fig. 1, where the practical and theoretical results are shown in coloured and dashed-grey lines, respectively. Again, it is obvious that there is a good match between practical and theoretical results.

Figure 2 shows the practical and theoretical reaction rate against reaction temperature, where the coloured and dashed-grey curves show the practical and theoretical calculations, respectively, with good matching in all of the five heating rates. The maximum reaction rate of the PET pyrolysis at heating rates of 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 °C min−1 was found to be 0.000089, 0.000449, 0.00092, 0.00188, and 0.00386 s−1, respectively. Thus, the reaction rate increased by approximately 43 times with increasing the heating rates by 16 times, i.e., from 0.5 to 8 °C min−1.

One of the kinetic modelling methods, ASTM-E698 (Eq. 3), was used to calculate the Ea and showed 165.6 kJ mol−1 with R2 = 0.9989, as shown in Fig. 3a. This is in agreement with the Ea value reported by Saha and Ghoshal which was 162.15 kJ mol−1 using the ASTM-E698 method [35].

While the Flynn–Wall and Ozawa (FWO) method (Eq. 4) showed a variation of Ea during the reaction progress in the range of 166–180 kJ mol−1, as shown in Fig. 3b. The results herein are lower than those reported by Yao et al. [36], who reported 184–269 kJ mol−1. This is maybe due to the fact that they did not specify the plastic waste that they used along with the high heating rates used (15, 25, and 35 °C min−1).

The differential iso-conversional method also was used to calculate the kinetic parameters [Ea along with the pre-exponential factor (ko)] using the AKTS software by plotting of the natural logarithm of the reaction rate in (s−1) against the inverse of the temperature (T−1), as shown in Fig. 4a. In Fig. 4b, a variation in the Ea value was shown to be in the range of 165–195 kJ mol−1. Interestingly, the results herein are in line with the work done by Jenekhe and Sun, where they reported Ea values of 173.6–205.8 kJ mol−1 using the differential iso-conversional method [37]. At the start of the PET pyrolysis reaction where α = 0, the activation energy was 165 kJ mol−1. This is in agreement with work done by Cooney and Wiles [38], where the Ea value of the initial pyrolysis stage using Kissinger’s Method was 163 kJ mol−1. This activation energy value stayed relatively constant, while the reaction progress was increasing up to α = 0.3, i.e., 30% of the reaction progress, while the pre-exponential factor; ln(A(α) f(α) is ~ 22 s−1. This high Ea value at the start of the pyrolysis reaction could be attributed to the depolymerization of the polyethylene terephthalate polymer, which requires high energy to cleave the bonding within the polymer structure for the PET pyrolysis reaction, to initiate and progress. With the pyrolysis reaction progressing > α = 0.3, the activation energy value slightly increased to reach 195 kJ mol−1 at α = 0.9, while the pre-exponential factor; ln(A(α) f(α) is ~ 26 s−1. This is again in line with the work reported by Cooney and Wiles [38], where the Ea value increased to 202 kJ mol−1.

The prediction of PET pyrolysis

The step-based prediction of PET pyrolysis

The predictions of PET pyrolysis using a step-based heating regime are shown in Fig. 5a–d. For all of the four predictions, the final pyrolysis temperature was set to 500 °C, as this was in line with total decomposition from the TGA results. Additionally, all heating regimes began at 20 °C to indicate heating from ambient room temperature. In Fig. 5a, the PET was heated from 20–420 °C at 50 °C min−1 and then from 420–500 °C at 25 °C min−1. It is evident that the reaction had appeared to complete after 11 min from the reaction rate curve. Interestingly, the maximum reaction rate observed was 0.014 s−1 at approximately 9.77 min. In Fig. 5b, the heating regime of 20–400 °C at 100 °C min−1 and 400–500 °C at 50 °C min−1 was utilized. For this sample condition, the peak reaction rate was shown to be 0.029 s−1 after approximately 5.42 min. From the reaction rate curve, it can be seen that the curve does not reach its baseline of 0 and is incomplete, therefore, implying an incomplete reaction. This is likely due to the heating rates used of 100 and 50 °C min−1, respectively. If the reaction had occurred for longer at 50 °C min−1 or dwelled at the final reaction temperature of 500 °C, it would have reached completion. Figure 5c, on the other hand, is subjected to a heating regime of 100 °C min−1 from 20–320 °C and then 20 °C min−1 from 320–500 °C, respectively. However, in this case, the lower latter heating rate supplied allowed the observed reaction to reach completion. In this instance, the peak reaction rate observed was 0.010 s−1 after 9.86 min. Finally, Fig. 5d is heated from 20 to 450 °C at a heating rate of 100 °C min−1 and then from 450–500 at a heating rate of 5 °C min−1. The maximum observed reaction rate was 0.011 s−1 after 5.42 min. Interestingly, the curve in this sample appeared to have a shoulder and this is likely due to the rapid change in heating rate from 100 to 5 °C min−1, respectively.

Isothermal prediction of PET pyrolysis

The isothermal prediction of PET pyrolysis showing 14 different isotherms at every 10 °C temperature change over the temperature range of 420–550 °C is shown in Fig. 6a, b. Figure 6a shows the reaction progress over the first minute, whereas Fig. 6b shows the reaction profile over the first 5 min. Evidently, from Fig. 6a, at reaction temperatures of 490 °C and above, the reaction reached completion (α = 1) in the short timeframe of 1 min. This rapid decomposition indicates that these temperatures would be ideal for rapid conversion. However, at lower than 490 °C, for example, 480, 470, and 460 °C, the reaction progress only reached α values of 0.93, 0.81, and 0.55, respectively, after the first minute. As Fig. 6b shows the decomposition over a broader time range, it is worth noting that temperatures such as 450–480 °C that did not reach (α = 1) in Fig. 6a have reached reaction completion when the timeframe is expanded to 5 min of operation. Below 450 °C shows a much slower reaction and indicates that the reaction has not reached completion in this case. This further indicates that in order for successful pyrolysis to occur of PET temperatures exceeding 450 °C should be used.

Non-isothermal prediction of PET pyrolysis

Figure 7 shows the non-isothermal prediction of PET pyrolysis over the temperature range of 350–500 °C. It is not surprising that the decomposition temperature shifted slightly toward higher reaction temperatures. For example, by increasing the heating rates from 10 up to 30 °C min−1, the peak reaction rates observed were 0.0051, 0.0077, 0.0104, and 0.0159 s−1, respectively. In all of the four heating rates used (10, 15, 20, and 30 °C min−1) for the prediction, the reaction profile and reaction rate curves appeared to be consistent.

The in-situ gaseous monitoring of PET pyrolysis

During the pyrolysis process, two main reactions occur: cracking which breaks down the carbon chain and the charring reaction which aids to re-build up higher molecular weight products [39]. For instance, polyolefins (PP and HDPE) are composed of a saturated hydrocarbon chain, where the thermal decomposition takes place randomly by a radical scission mechanism [40, 41]. However, due to the aromatic nature of PS, it decomposes into styrene monomers (70.6 wt.%), oligomers, and other secondary aromatic products. On the other hand, PET is composed of terephthalic acid and ethylene glycol monomers, and thus upon pyrolysis, various oxygenates and aromatics products are produced. The pyrolysis residue in the case of polyolefins was negligible, unlike PET that showed a value of 7 wt.% residue [40]. Barbarias et al. reported that the main PET pyrolysis fraction was a gaseous stream (CO and CO2), with a product yield of 42.8 wt.%, along with 37.4 wt.% for the solid residue (benzoic and benzoyl formic acid) and 12.8 wt.% for oil fraction. PET plastic consists of chain-like backbones of synthetic polymers that are made of bis-hydroxyethyl-terephthalate monomer, and with thermal cracking or pyrolysis, it evolved various gaseous emissions. The PET pyrolysis is a complex process that releases different types of products such as aromatic compounds, such as benzene and toluene and aliphatic hydrocarbons C1–C4 such as methane and ethane along with the typical pyrolytic emissions (CO2, CO, H2, and H2O) [20, 42,43,44]. Furthermore, other species could be released such as aldehydes, carboxylic acids (benzoic acid, acetyl benzoic acid, methyl benzoic acid, and ethyl benzoic acid), esters (vinyl benzoate and its derivatives), ketones (benzophenone and acetophenone), and terephthalic acid and vinyl terephthalate [20, 45,46,47]. The complexity of such reaction is due to the possibility of several side interactions between free radicals during the scission of the polymeric hydrocarbon chain such as intramolecular or intermolecular exchange and six-membered transition state reactions [27]. Figure 8 shows the in-situ monitoring of the evolved gaseous emissions using the mass spectrometer which offers rapid analysis and is not limited to the shape, colour, impurities, or dimensional limit as in other techniques such as Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and Raman spectroscopy [1]. Herein, the temperature was recorded using a thermocouple that was set in the middle of the fixed bed reactor as shown from the blue-dashed line in Fig. 8. The PET pyrolysis herein occurred in one stage, which is in line with the TGA results with a similar heating rate, while the DSC results in Additional file 1: Figure S3 showed that the pyrolysis occurred in two stages. Figure 8 shows the pyrolysis reaction was in the temperature range of 390–530 °C, while the TGA result was in the range of 382–490 °C (heating rate of 4 °C min−1). The in-situ MS data showed that the main emissions are C1 hydrocarbons at m/z = 15 and H–O-C=O (CHO2) at m/z = 45. The in-situ MS profile also showed some relatively low emissions as shown from the inset (Fig. 8), which showed the evolution of various forms of hydrocarbons such as C2 hydrocarbons at m/z = 27, C5 hydrocarbons at m/z = 42, and C6 hydrocarbons at m/z = 78. Furthermore, other related emissions were shown as acetaldehyde or carbon dioxide at m/z = 44, the fragment of O–CH=CH2 at m/z = 43, hydrogen gas at m/z = 2, water at m/z = 18, and, finally, m/z = 29 that confirms the existence of acetaldehyde as following the same trend as with m/z = 44. This is in agreement with the work done by Garozzo et al. as they reported the presence of the O–CH=CH2 fragment and m/z of 17 for -OH species that confirmed the metastable transitions of the fragments, implying the existence of the open-chain structure with C(=O)O and −CH=CH2 groups [48]. Acetaldehyde was the first gaseous product that evolved and finished, as shown in Fig. 8, and this was confirmed by the m/z = 44 and 29 with the same evolution trend. This is in line with the work reported by Dhahak et al. [20], as they reported that acetaldehyde was the first detected gas followed by the following gases; benzoic acid, terephthalic acid, and benzene. Traces of benzene was detected herein in two peaks as shown in Additional file 1: Figure S4, with a large peak and small shoulder. This is also in agreement with the literature, as it was explained that those two peaks are due to the decarboxylation of benzoic acid (first peak) and terephthalic acid (second peak) [33]. Dhahak et al. reported that the major three gaseous compounds detected during the pyrolysis of PET were acetaldehyde, benzoic acid, and vinyl terephthalate [20]. During the PET pyrolysis, the depolymerisation reaction starts to occur at the weak bonding points within the ester polymeric structure, such as the C–O bonding and the polymer chain near the C=O bonding [27]. It is worth noting that the evolved short-chain hydrocarbon (C1-C4 hydrocarbons) emissions can be combusted to provide some of the required reaction heat during the pyrolysis process [27].

Conclusion

Herein, with the aid of thermo-analytical data (TGA and DSC) along with kinetic modelling software, we evaluated and measured the kinetic triplet of polyethylene terephthalate pyrolysis to better understand the process at scale. Furthermore, three types of predictions (step prediction, non-isothermal, and isothermal) were made at higher heating rates to represent a realistic scenario that would occur in the industry. The differential iso-conversional method showed activation energy (Ea) values of 165–195 kJ mol−1, R2 = 0.99659. Additionally, the activation energy for PET pyrolysis was also evaluated using the ASTM-E698 (165.6 kJ mol−1, R2 = 0.9989) and integral methods such as Ozawa–Flynn–Wall (166–180 kJ mol−1).Finally, the in-situ online tracking of the gaseous emissions using mass spectrometry of PET pyrolysis showed that the pyrolysis gaseous emissions, C1-hydrocarbons (m/z =15) and H-O-C=O (m/z =45) are present along with C2 hydrocarbons (m/z = 27), C5 hydrocarbons (m/z = 42), C6 hydrocarbons (m/z = 78), acetaldehyde (m/z = 44, 29), the fragment of O-CH=CH2 (m/z = 43), hydrogen (m/z = 2) and water (m/z = 18). Future work could involve the use of kinetic modelling approaches such as the methods used herein to help determine how certain impurities or mixed wastes alongside PET can affect kinetic parameters and the predictions made in this study to help visualise problems that may occur in real-world scenarios such as industrial pyrolysis processes. This work can be used as a baseline kinetic modelling benchmark for pure PET bottle samples. The kinetic parameters evaluated herein can be used as a prerequisite in process modelling applications and the scale-up of PET pyrolysis worldwide. This will effectively allow this abundant waste stream to be converted into useful products such as energy and help to promote concepts such as the circular economy and the waste management hierarchy. Additionally, it will alleviate the amount of waste plastic that is conventionally sent to landfill or end in the aquatic ecosystem, by providing another end-of-life pathway for this non-biodegradable waste.

Availability of data and materials

The data and results obtained herein are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PET:

-

Polyethylene terephthalate

- FWO:

-

Flynn–Wall and Ozawa method

- E a :

-

Activation energy

- Mt:

-

Million tonnes

References

Zhang X, Zhang H, Yu K, Li N, Liu Y, Liu X, Zhang H, Yang B, Wu W, Gao J, Jiang J (2020) Rapid monitoring approach for microplastics using portable pyrolysis-mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 92:4656–4662

Al-Salem SM, Lettieri P, Baeyens J (2009) Recycling and recovery routes of plastic solid waste (PSW): a review. Waste Manage 29:2625–2643

Wagner M, Engwall M, Hollert H (2014) Editorial: (micro)plastics and the environment. Environ Sci Eur 26:16

Beagan N, O’Connor KE, Del Val IJ (2020) Model-based operational optimisation of a microbial bioprocess converting terephthalic acid to biomass. Biochem Eng J 158:107576

Kamali AR, Yang J, Sun Q (2019) Molten salt conversion of polyethylene terephthalate waste into graphene nanostructures with high surface area and ultra-high electrical conductivity. Appl Surf Sci 476:539–551

Geyer R, Jambeck JR, Law KL (2017) Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci Adv 3:e1700782

Zhang J, Hu Q, Qu Y, Dai Y, He Y, Wang C-H, Tong YW (2020) Integrating food waste sorting system with anaerobic digestion and gasification for hydrogen and methane co-production. Appl Energy 257:113988

Gallo F, Fossi C, Weber R, Santillo D, Sousa J, Ingram I, Nadal A, Romano D (2018) Marine litter plastics and microplastics and their toxic chemicals components: the need for urgent preventive measures. Environ Sci Eur 30:13

Zhang B, Xu T, Yin D, Wei S (2020) The potential relationship between neurobehavioral toxicity and visual dysfunction of BDE-209 on zebrafish larvae: a pilot study. Environ Sci Eur 32:25

Xu L, Zhang L-Y, Song H, Dong Q, Dong G-H, Kong X, Fang Z (2019) Catalytic fast pyrolysis of polyethylene terephthalate plastic for the selective production of terephthalonitrile under ammonia atmosphere. Waste Manage 92:97–106

Farrell CC, Osman AI, Doherty R, Saad M, Zhang X, Murphy A, Harrison J, Vennard ASM, Kumaravel V, Al-Muhtaseb AH, Rooney DW (2020) Technical challenges and opportunities in realising a circular economy for waste photovoltaic modules. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 128:109911

Sinha V, Patel MR, Patel JV (2010) Pet waste management by chemical recycling: a review. J Polym Environ 18:8–25

Zhou X, Wang C, Fang C, Yu R, Li Y, Lei W (2019) Structure and thermal properties of various alcoholysis products from waste poly(ethylene terephthalate). Waste Manage 85:164–174

Lopez G, Artetxe M, Amutio M, Bilbao J, Olazar M (2017) Thermochemical routes for the valorization of waste polyolefinic plastics to produce fuels and chemicals. A review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 73:346–368

Arabiourrutia M, Lopez G, Artetxe M, Alvarez J, Bilbao J, Olazar M (2020) Waste tyre valorization by catalytic pyrolysis—a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 129:109932

Wang F, Gao N, Quan C, López G (2020) Investigation of hot char catalytic role in the pyrolysis of waste tires in a two-step process. J Anal Appl Pyrol 146:104770

Al-asadi M, Miskolczi N (2018) Pyrolysis of polyethylene terephthalate containing real waste plastics using Ni loaded zeolite catalysts. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 154:012021

Das P, Tiwari P (2019) Thermal degradation study of waste polyethylene terephthalate (PET) under inert and oxidative environments. Thermochim Acta 679:178340

Awaja F, Pavel D (2005) Recycling of PET. Eur Polymer J 41:1453–1477

Dhahak A, Grimmer C, Neumann A, Rüger C, Sklorz M, Streibel T, Zimmermann R, Mauviel G, Burkle-Vitzthum V (2020) Real time monitoring of slow pyrolysis of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) by different mass spectrometric techniques. Waste Manage 106:226–239

Kawecki D, Scheeder PRW, Nowack B (2018) Probabilistic Material Flow Analysis of Seven Commodity Plastics in Europe. Environ Sci Technol 52:9874–9888

Lee J, Lee T, Tsang YF, Oh J-I, Kwon EE (2017) Enhanced energy recovery from polyethylene terephthalate via pyrolysis in CO2 atmosphere while suppressing acidic chemical species. Energy Convers Manage 148:456–460

Al-Sabagh AM, Yehia FZ, Harding DRK, Eshaq G, ElMetwally AE (2016) Fe3O4-boosted MWCNT as an efficient sustainable catalyst for PET glycolysis. Green Chem 18:3997–4003

Oh S-Y, Seo T-C (2019) Upgrading biochar via co-pyrolyzation of agricultural biomass and polyethylene terephthalate wastes. RSC Adv 9:28284–28290

Oh D, Lee HW, Kim Y-M, Park Y-K (2018) Catalytic pyrolysis of polystyrene and polyethylene terephthalate over Al-MSU-F. Energy Procedia 144:111–117

Ayodeji SO, Oni TO (2019) Thermal pyrolysis production of liquid fuel from a mixture of polyethylene terephthalate and polystyrene. Heat Transfer-Asian Res 48:1648–1662

Brems A, Baeyens J, Vandecasteele C, Dewil R (2011) Polymeric cracking of waste polyethylene terephthalate to chemicals and energy. J Air Waste Manag Assoc 61:721–731

Ganeshan G, Shadangi KP, Mohanty K (2018) Degradation kinetic study of pyrolysis and co-pyrolysis of biomass with polyethylene terephthalate (PET) using Coats-Redfern method. J Therm Anal Calorim 131:1803–1816

Mishra RK, Sahoo A, Mohanty K (2019) Pyrolysis kinetics and synergistic effect in co-pyrolysis of Samanea saman seeds and polyethylene terephthalate using thermogravimetric analyser. Bioresour Technol 289:121608

https://www.akts.com/akts-thermokinetics-tga-dsc-dta-tma-ftir-ms/akts-thermokinetics-discontinuous-help-e-learning.html. Accessed 10 May 2020 at 11 am.

Vyazovkin S, Chrissafis K, Di Lorenzo ML, Koga N, Pijolat M, Roduit B, Sbirrazzuoli N, Suñol JJ (2014) ICTAC Kinetics Committee recommendations for collecting experimental thermal analysis data for kinetic computations. Thermochim Acta 590:1–23

Osman AI, Abdelkader A, Johnston CR, Morgan K, Rooney DW (2017) Thermal investigation and kinetic modeling of lignocellulosic biomass combustion for energy production and other applications. Ind Eng Chem Res 56:12119–12130

Dhahak A, Hild G, Rouaud M, Mauviel G, Burkle-Vitzthum V (2019) Slow pyrolysis of polyethylene terephthalate: online monitoring of gas production and quantitative analysis of waxy products. J Anal Appl Pyrol 142:104664

Park Y-K, Jung J, Ryu S, Lee HW, Siddiqui MZ, Jae J, Watanabe A, Kim Y-M (2019) Catalytic co-pyrolysis of yellow poplar wood and polyethylene terephthalate over two stage calcium oxide-ZSM-5. Appl Energy 250:1706–1718

Saha B, Ghoshal AK (2006) Model-fitting methods for evaluation of the kinetics triplet during thermal decomposition of poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) soft drink bottles. Ind Eng Chem Res 45:7752–7759

Yao Z, Yu S, Su W, Wu W, Tang J, Qi W (2020) Kinetic studies on the pyrolysis of plastic waste using a combination of model-fitting and model-free methods. Waste Manage Res 38:77–85

Jenekhe SA, Lin JW, Sun B (1983) Kinetics of the thermal degradation of polyethylene terephthalate. Thermochim Acta 61:287–299

Cooney JD, Day M, Wiles DM (1983) Thermal degradation of poly(ethylene terephthalate): a kinetic analysis of thermogravimetric data. J Appl Polym Sci 28:2887–2902

Horton SR, Woeckener J, Mohr R, Zhang Y, Petrocelli F, Klein MT (2016) Molecular-level kinetic modeling of the gasification of common plastics. Energy Fuels 30:1662–1674

Li H, Tan Y, Ditaranto M, Yan J, Yu Z (2017) Capturing CO2 from biogas plants. Energy Procedia 114:6030–6035

Martı́n-Gullón I, Esperanza M, Font R (2001) Kinetic model for the pyrolysis and combustion of poly-(ethylene terephthalate) (PET). J Anal Appl Pyrol 58–59:635–650

Kumagai S, Yamasaki R, Kameda T, Saito Y, Watanabe A, Watanabe C, Teramae N, Yoshioka T (2017) Tandem μ-reactor-GC/MS for online monitoring of aromatic hydrocarbon production via CaO-catalysed PET pyrolysis. React Chem Eng 2:776–784

Sophonrat N, Sandström L, Johansson A-C, Yang W (2017) Co-pyrolysis of mixed plastics and cellulose: an interaction study by Py-GC×GC/MS. Energy Fuels 31:11078–11090

Osman AI (2020) Mass spectrometry study of lignocellulosic biomass combustion and pyrolysis with NOx removal. Renew Energy 146:484–496

Artetxe M, Lopez G, Amutio M, Elordi G, Olazar M, Bilbao J (2010) Operating conditions for the pyrolysis of poly-(ethylene terephthalate) in a conical spouted-bed reactor. Ind Eng Chem Res 49:2064–2069

Dziȩcioł M, Trzeszczyński J (2001) Temperature and atmosphere influences on smoke composition during thermal degradation of poly(ethylene terephthalate). J Appl Polym Sci 81:3064–3068

Yoshioka T, Grause G, Eger C, Kaminsky W, Okuwaki A (2004) Pyrolysis of poly(ethylene terephthalate) in a fluidised bed plant. Polym Degrad Stab 86:499–504

Garozzo D, Giuffrida M, Montaudo G, Lenz RW (1987) Mass spectrometric characterization of poly(ethylene terephthalate-co-p-oxybenzoate). J Polym Sci Part A Polym Chem 25:271–284

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support UKRI project “Advancing Creative Circular Economies for Plastics via Technological-Social Transitions” (ACCEPT Transitions, EP/S025545/1). A.S.A-F would like to extend his sincere appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University with support from project # No. RGP-1435-078.

Funding

The research is funded through UKRI project “Advancing Creative Circular Economies for Plastics via Technological-Social Transitions” (ACCEPT Transitions, EP/S025545/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AIO conceived the idea, prepared, and tested the PET pyrolysis. AIO, CF, AHM, ASA-F, JH, and DWR extracted and discussed the kinetic modelling and emission tests. All authors discussed and contributed to the writing of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Figure S1.

The PET sample used herein. Figure S2. The % integrated mass derived from TGA results of PET pyrolysis at heating rates of 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 8 °C min−1. The integration of the DTG curve is shown in yellow and simulation results are shown by black lines. Figure S3. The DSC-TGA thermogram of the PET pyrolysis at heating rate of 0.5 °C min−1 (a) and 1 °C min−1 (b) under nitrogen atmosphere. Figure S4. Benzene evolution during the PET pyrolysis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Osman, A.I., Farrell, C., Al-Muhtaseb, A.H. et al. Pyrolysis kinetic modelling of abundant plastic waste (PET) and in-situ emission monitoring. Environ Sci Eur 32, 112 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-020-00390-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-020-00390-x