Abstract

There is some evidence that housing accessibility, external housing-related control beliefs (HCB) and activities of daily living (ADL) are associated in complex ways; however, these pathways have not been explored in younger old. The aim was to assess the role of external HCB in the relationship between housing accessibility and ADL by applying moderation and mediation models. This was a cross-sectional study involving 366 community-living 67–70 years old participants from the Skåne part of the Swedish National Study of Aging and Care. We assessed moderation by including an interaction term in a logistic regression analysis (significant if p value < 0.05). We assessed mediation with a series of regression analyses with effect size measures expressed as proportion mediated and its 95% confidence interval (CI). In the absence of statistically significant interaction there was no support for external HCB as a moderator. There was evidence for partial mediation as external HCB was associated with ADL when controlled for housing accessibility, while housing accessibility remained associated with independence in ADL when adjusted for external HCB. The proportion mediated was 6% (95% CI 1; 14). While the results did not support external HCB as a moderator, external HCB mediated the association between housing accessibility and ADL. These results were different from previous findings suggesting that external HCB plays a marginally significant moderating and mediating role among very old. Such differences call for further studies that would allow further exploration and validation of the findings at different stages of the ageing process, preferably utilizing longitudinal study designs.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Perceived control refers to a person’s beliefs to determine one’s internal states and behavior, influence one’s environment, and/or bring about desired outcomes (Wallston et al. 1987). People with a higher sense of control have been shown to be better adapted to cope with health problems, both emotionally and practically (Kempen et al. 2005). Control beliefs are most often used as a general measure of autonomy. However, multidimensional and domain-specific conceptions of control were shown to be advantageous, as for older people they were found to be better predictors of behavioral outcomes within domains such as intellect or health (Lachman 1986). Given the importance of the home environment along the process of ageing, the Housing-related Control Beliefs Questionnaire (HCQ) was designed to capture control beliefs specifically in the housing domain to provide more insights into links between the (physical) environment and the ageing person (Oswald et al. 2003).

Housing accessibility, defined as a relationship between the person’s functional capacity and the demands of the physical environment (Iwarsson and Ståhl 2003), is an indicator of person–environment (P–E) fit (Lawton and Nahemow 1973; Lawton 1986), and is central along the process of ageing as it influences well-being (Kylén et al. 2017; Iwarsson 2005). Housing accessibility influences activities of daily living (ADL), and the association becomes stronger with decreasing functional capacity in particular (Iwarsson 2005). This is supported by the Ecological Theory of Ageing (Lawton and Nahemow 1973; Lawton 1986), where it is argued that the balance between individual competencies and environmental demands is important for adaptive functioning. Nevertheless, a dynamic view taking into account factors playing a role in the association between housing aspects and ADL is lacking.

Higher external housing-related control beliefs (HCB), indicating more control assigned to powerful others, fate or chance, are related to more functional limitations, worse psychological well-being and more dependence in ADL among younger old as well as very old people (Tomsone et al. 2013; Wahl et al. 2009; Kylén et al. 2017). The role of HCB is of a particular interest as control beliefs are modifiable (Tennstedt et al. 1998; Petrie et al. 2002) and thus could be intervened upon to improve housing environment related health outcomes. As the role of general control beliefs has been shown to vary with age, such that the control beliefs are quite stable during the midlife and start declining in later life (Drewelies et al. 2017), exploring the role of HCB in different stages of the process of ageing is crucial. It could therefore be expected that in cohorts of different ages, the role of HCB might also be different, that is, with stronger external HCB in older versus younger old age. Further studies to explore such dynamics are warranted as they might help researchers, practitioners and policy-makers to better address the challenges when it comes to housing and the ageing population, such as when planning housing adaptations, relocations and many others.

There is evidence that control beliefs in general can moderate, alter the direction and/or strength of the effect, or mediate, explain the relationship between functional limitations and health-related outcomes. Specifically, it has been shown that HCB could play both, a moderating and a mediating role in the association between housing accessibility and independence in ADL, at least in the very old age (Wahl et al. 2009; Oswald et al. 2007). A study investigating the moderating role of external HCB in the very old individuals from Germany and Sweden found that those with a higher magnitude of accessibility problems and higher external HCB were less independent in ADL, while this was less the case for those with lower external HCB, although the result was marginally significant, p value < 0.10 (Wahl et al. 2009). This indicates that in the very old age assigning control over one’s housing has an impact on the association between P–E fit and independence in ADL (Wahl et al. 2009). Interestingly, in a similar setting it has been found that HCB explained some of the association between the magnitude of the accessibility problems and independence in ADL, and thus acted as a mediator (Oswald et al. 2007). In Germany, UK, Hungary and Latvia, the higher the magnitude of accessibility problems, the more the participants thought that others, fate, chance or luck determined what happens at home and the more dependent they were in ADL. In Sweden, the lower the magnitude of accessibility problems, the more the participants believed that they were responsible for what happens at home and the more they were independent in ADL (Oswald et al. 2007). These cross-sectional analyses provide evidence that HCB plays different roles in the association between housing accessibility and independence in ADL, at least in the very old. Because the role of external HCB as a moderator and/or mediator might be different in individuals in different stages of ageing, we designed the present study to assess its role as a moderator and mediator in the association between housing accessibility and independence in ADL among community-living younger old people.

2 Methods

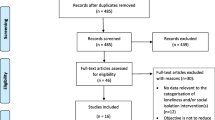

We conducted a cross-sectional study focusing on housing and health in a sub-sample of 371 participants from the 67–70 years old cohort from the Gott Åldrande i Skåne (GÅS) [Good Aging in Skåne] project (Kylén et al. 2014), which is part of the Swedish National Study of Aging and Care (SNAC) (Ekström and Elmståhl 2006; Lagergren et al. 2004). Data on age, sex, marital status, ADL, housing accessibility and HCB were collected as part of the cross-sectional Home and Health in the Third Age Study (2010–2011). For eligibility see (Kylén et al. 2014). Data on geographical location, level of education and financial situation were collected as part of the general SNAC-GÅS study (2008–2010).

2.1 Instruments and variables

Socio-demographic characteristics included were age, sex, marital status (married/cohabitant; unmarried/divorced/widowed), level of education (elementary school/less; secondary school; 1 year more than secondary school/university degree), financial situation (sufficient: the needs covered very well/well; insufficient: the needs covered poorly/not at all), geographical location (urban: city/densely populated area; rural: small villages in the countryside), type of housing (one-family; multi-family) and years that the participant has been living in the current dwelling. Except for age and sex, these characteristics were self-reported.

The ADL Staircase was used to assess dependence in ADL and included five personal and four instrumental ADL items (Sonn and Asberg 1991). It was administered using a combination of interview and observation. The assessment was recorded on a three-point scale (independent, partly dependent, dependent), with dependence defined in terms of assistance from another person. To counteract the ceiling effect when used in populations with anticipated lower levels of dependence (Iwarsson et al. 2009) for those who were rated as independent in a particular activity the data collector asked whether the participant performed the specific task with difficulty (yes/no). For each item, a new ordinal variable based on the ADL Staircase assessment and perceived difficulty in ADL performance was created: independent based on ADL Staircase, no difficulty (0); independent based on ADL Staircase, with difficulty (1); partly dependent based on ADL Staircase (2); dependent based on ADL Staircase (3). Due to high numbers of independent individuals in our sample, independence in ADL was used as a dichotomous variable: independent (score = 0) versus independent with difficulty, partly dependent or dependent (score = 1). The ADL Staircase was shown to be reliable and valid for the assessment of 74–84 years old people’s functional ability (Iwarsson 2005).

Housing accessibility was assessed with the Housing Enabler (HE) (Iwarsson and Slaug 2010). First, a trained rater administered the personal component of accessibility assessing functional limitations (12 items) and dependence on mobility devices (two items) by a combination of interview and observation as present/not present. Secondly, the environmental component was assessed based on observations of the actual environment in a detailed rating of environmental barriers (161 items) as present/not present. Last, a HE score was calculated that quantified the magnitude of accessibility problems per case, predicting the load caused by the individual combination of functional limitations and environmental barriers. The higher the HE score, the greater the housing accessibility problems. The HE score is always 0 if the individual has no functional limitations/dependence on mobility devices, regardless of the presence of environmental barriers, with the maximum possible score of 1844. The instrument has demonstrated adequate validity and reliability (Iwarsson et al. 2012). In this study, housing accessibility was used as a continuous variable.

Control beliefs in relation to home were self-rated using the HCQ, which captures internal control (8 items), external control-powerful others (8 items), and external control-chance (8 items) (Oswald et al. 2003). Internal control denotes that housing-related outcomes are dependent on own behavior, and external control means that an external power such as another person is responsible or that things happen by luck, chance, or fate. The participants were asked to rate each statement on a five-point scale (1-I do not at all agree; 5-I agree very much), which resulted in a total score ranging 8–40 for each domain, and 16–80 for external control. Higher scores indicated higher perceived control in the domain of internal control whereas higher scores in the domains of external control indicated lower perceived control. Due to low internal consistency (α = 0.4), internal control was excluded from the analysis. We used a score combining the two dimensions of external control (Oswald et al. 2007), as it then reached an acceptable level of internal consistency (α = 0.7). In previous studies, HCQ showed comparable internal consistencies of the subscales in 66–69 years old and 65–91 years olds, and good test–retest reliability in 65–91 years olds (Oswald et al. 2003).

As 10–15% of the values for each of the external domains were missing, we imputed mean values calculated from at least 5/8 present items for each domain separately, which resulted in three missing values for the total external control score. As the external HCB scores were relatively low, to ease the interpretation they were dichotomized into <45 versus> = 45 scores, the latter representing 15% of the participants with the highest scores.

2.2 Statistical analysis

To describe the differences between the participants dependent or independent in ADL, we used Chi square and t tests. To assess whether any of the sociodemographic variables might be potential confounders, we tested whether including them into the multivariable logistic regression model changed the odds ratio of housing accessibility on the independence in ADL by ≥ 10%.

The strength of correlations between the variables was assessed by Spearman’s correlation coefficients (rs).

The analysis was conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) and RStudio (RStudio, Inc., Boston).

2.2.1 Assessing the role of external HCB as a moderator

To test the role of external HCB as a moderator we performed logistic regression with independence in ADL as the dependent variable. In simple logistic regression, we predicted independence in ADL from housing accessibility. We then adjusted this model for external HCB, and finally, to assess the moderation we included an interaction term of housing accessibility and external HCB. We calculated odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI).

2.2.2 Assessing the role of external HCB as a mediator

To assess the mediating effect of external HCB in the association of housing accessibility and independence in ADL we tested whether (Baron and Kenny 1986):

-

1.

Housing accessibility predicted independence in ADL (path c, total effect = c′ + a × b);

-

2.

Housing accessibility predicted external HCB (path a);

-

3.

External HCB predicted independence in ADL when controlled for housing accessibility (path b); and

-

4.

Housing accessibility predicted independence in ADL when controlled for external HCB (path c’, direct effect).

For these analyses, we used regression coefficients (B) and their standard errors (SE) derived from the simple and multivariable logistic regression. Due to dichotomized mediator and outcome, to make the coefficients comparable across the equations, each coefficient was multiplied by the standard deviation (SD) of the independent variable in the equation and then divided by the SD of the dependent variable in that equation (MacKinnon and Dwyer 1993). As effect size measures we used indirect effect (a × b) and proportion mediated (Pmed) (Alwin and Hauser 1975). Indirect effect can be interpreted as the amount by which ADL is expected to increase indirectly through HCB per unit change in housing accessibility. Pmed (indirect effect/total effect) is one of the most commonly used effect size measures in mediation models, and although it is usually interpreted as a proportion of the total effect mediated, it can exceed one and have negative values, and thus cannot be interpreted as a true proportion (Preacher and Kelley 2011). For indirect effect and Pmed the 95% CI were obtained by bias-corrected bootstrap with 10,000 resamples.

3 Results

The study sample with no data missing (N = 366) consisted of 43% men; the average age was 68 years; 64% were married/cohabiting, and nearly one-third had 1 year more than secondary school or a university degree (Table 1). The majority (89%) of participants were living in urban areas; 59% lived in multi-family dwellings and on average, they had lived in their current housing for approximately 19 years (Table 1). More than half of the participants (52%) had no housing accessibility problems (Table 1), with the scores of the remainder of the sample ranging from 1 to 386.

The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants with and without dependence and/or difficulties in ADL were similar; they did not change the effect of housing accessibility on ADL by ≥ 10%. Therefore, the moderation and mediation models were not adjusted (Table 1).

Independence in ADL was moderately correlated with housing accessibility (rs = 0.44, p value < 0.001). ADL and housing accessibility were weakly and very weakly correlated with external HCB (rs = 0.20 and 0.17, respectively; corresponding p values ≤ 0.001).

The logistic regression analyses indicated that housing accessibility predicted independence in ADL, and this association remained statistically significant after adjusting for external HCB (OR 1.02, 95% CI 1.01–1.02; Table 2). Because the interaction effect was not significant between housing accessibility and external HCB (p value > 0.05), there was no evidence for a moderating effect of external HCB.

Housing accessibility predicted external HCB and independence in ADL (B 0.24, SE 0.07 and B 0.54, SE 0.06; Fig. 1). There was evidence for partial mediation as external HCB predicted independence in ADL when controlled for housing accessibility (B 0.12, SE 0.06), while housing accessibility remained associated with independence in ADL (B 0.51, SE 0.09; Fig. 1). Higher external HCB were related to more dependence in ADL when adjusted for housing accessibility. The indirect effect was 0.03 (95% CI 0.01–0.07) implying that dependence in ADL increases by 0.03 for every unit increase in housing accessibility indirectly though HCB; the Pmed was 0.06 (95% CI 0.01–0.14).

Path model, regression coefficients and their standard errors depicting the role of housing-related control beliefs in mediating the effect of housing accessibility on independence in activities of daily living (N = 366). ADL activities of daily living, HCB housing related control beliefs, B unstandardized regression coefficient, SE standard error

4 Discussion

We did not find support for external HCB as a moderator, but found modest support for external HCB as a mediator on the association between housing accessibility and independence in ADL in community-living younger old people. Declines in control become steeper after the age of 70 (Drewelies et al. 2017), which may explain the absence of or rather weak effects in both the moderation and mediation models because among younger old people external HCB might not yet be playing a major role.

Although it is plausible that HCB could play a moderating role under the assumption that it is (a proxy of) pre-existing, relatively stable, individual characteristics that would increase or decrease the likelihood that housing accessibility would lead to independence in ADL, we did not find the evidence of HCB as a moderator in our sample. In a cross-sectional study among the very old, however, the borderline significant moderating effect of external HCB was detected (Wahl et al. 2009). While we were not able to use the same categorization of the moderator as in the aforementioned study in the very old due to the data properties in our study, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the detected differences in the findings could be attributed to the age differences in the study populations.

Our results provided some support for external HCB as a mediator, but this indirect association was minor. In contrast, the previous study among very old people found that internal, and not external HCB, mediated the association between housing accessibility and independence in ADL in a Swedish subsample (Oswald et al. 2007). Although internal HCB could not be used in our sample due to low internal consistency, preliminary analyses did not provide any evidence for internal HCB as a mediator nor as a moderator. Such opposing results from the present younger old and the previous very old sample are still suggestive of different roles of internal and external HCB along the process of ageing.

With few missing values, exclusion of only one per cent (5/371) of the participants prevented attrition bias. However, while the sample contained very detailed and unique information on housing and health, given a very fit sample of participants, the sample size to investigate the associations between housing accessibility problems, ADL and external HCB was small and led to some challenges.

More than half of the participants had a HE score of zero, which implies no housing accessibility problems (52%). The remaining participants had a maximum score of 366, which was substantially lower than the possible maximum score in HE of 1844, indicating a relatively fit sample of participants.

We complemented ADL-Staircase with self-reported difficulty (Iwarsson et al. 2009). This way we were able to incorporate a more sensitive measure of ADL (Axmon et al. 2019), thus increasing the variance in the ADL variable, as it has also been the case in the very old (Iwarsson et al. 2009). Post-hoc analysis revealed that except for a weaker (rs = 0.16, p value = 0.002) correlation between ADL and housing accessibility when only using ADL without the difficulty dimension, the results were essentially the same as when using ADL measured with the difficulty dimension and thus generally are comparable to the previous studies. Next, due to high number of participants independent in ADL and non-Gaussian distribution even after transformations we dichotomized the outcome variable. This put some constraints on the analyses and comparisons to previous studies, as we were not able to categorize for example, external HCB and directly compare the results.

When it comes to practical implications, the role of HCB is of a particular importance as control beliefs are modifiable (Tennstedt et al. 1998; Petrie et al. 2002) and thus, given that they play a role in certain subgroups of the population, could be intervened upon to improve housing environment related health outcomes. For example, taking into consideration HCB and its changes over time might be a useful factor to consider when designing user-centred housing counselling interventions that are currently under development (Granbom et al. 2019).

In order to deepen the knowledge on HCB dynamics and their role in the complex ageing process, a general aim should therefore be to assess the role of HCB in relation to other potential moderators and/or mediators and their relative contributions. Given previous evidence that depressive symptoms are related to ADL capacity (Nyunt et al. 2012) as well as less perceived control over the housing situation (Kylén et al. 2017), adjustment to prior internalizing and/or externalizing mental health problems might be worthwhile.

Next, due to the variation in control throughout adulthood (Drewelies et al. 2017) and so far limited knowledge about HCB, it is important to continue exploring the role of HCB along the process of ageing, following the phenomenon over time and monitoring changes. Such analyses will require large sample sizes, multiple and rather extensive measures, and therefore should ideally be incorporated in larger cohort studies. Moreover, studying the role of HCB as a moderator and a mediator in a cross-sectional setting only informs us about the associations between the variables, and does not allow us to draw conclusions about the direction of the effects, causality or the mechanisms involved. The crucial next step is therefore to validate the role of HCB in longitudinal studies, where information on exposures, outcomes, moderators and mediators would be measured repeatedly and where variations over time would be accounted for in the data analyses.

In addition, perceived control beliefs in general do not necessarily reflect control-related behaviors (Schulz and Heckhausen 1999). Thus, by using the perceived HCB variable we were not able to account for when or whether participants had strong desires for independence in ADL, which might have played a role on the studied association. For further research, efforts should be made to integrate motivational and behavioral components in the data collection instruments.

5 Conclusions

With this study, we contribute to the evidence about the role of HCB in community-living younger old people, which has not been studied before. We did not find evidence for external HCB as a moderator, but we found some evidence that external HCB mediated a small proportion of the total association between housing accessibility and independence in ADL. In order to deepen the understanding of HCB further, in addition to addressing control beliefs in different stages of the process of ageing in the housing context, attempts should be made to also assess other pathways, preferably in longitudinal designs.

References

Alwin, D. F., & Hauser, R. M. (1975). The decomposition of effects in path analysis. American Sociological Review, 40, 37–47.

Axmon, A., Ekstam, L., Slaug, B., Schmidt, S. M., & Fänge, A. M. (2019). Detecting longitudinal changes in activities of daily living (ADL) dependence: Optimizing ADL staircase response choices. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022619853513.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173.

Drewelies, J., Wagner, J., Tesch-Römer, C., Heckhausen, J., & Gerstorf, D. (2017). Perceived control across the second half of life: The role of physical health and social integration. Psychology and Aging, 32(1), 76.

Ekström, H., & Elmståhl, S. (2006). Pain and fractures are independently related to lower walking speed and grip strength: Results from the population study “Good Ageing in Skåne”. Acta Orthopaedica, 77(6), 902–911.

Granbom, M., Szanton, S., Gitlin, L. N., Paulsson, U., & Zingmark, M. (2019). Ageing in the right place—A prototype of a web-based housing counselling intervention for later life. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2019.1634756.

Iwarsson, S. (2005). A long-term perspective on person–environment fit and ADL dependence among older Swedish adults. The Gerontologist, 45(3), 327–336.

Iwarsson, S., Haak, M., & Slaug, B. (2012). Current developments of the housing enabler methodology. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75(11), 517–521.

Iwarsson, S., Horstmann, V., & Sonn, U. (2009). Assessment of dependence in daily activities combined with a self-rating of difficulty. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 41(3), 150–156.

Iwarsson, S., & Slaug, B. (2010). Housing enabler—A method for rating/screening and analysing accessibility problems in housing (2nd revised ed.). Lund: Veten & Skapen HB & Slaug Enabling Development.

Iwarsson, S., & Ståhl, A. (2003). Accessibility, usability and universal design—Positioning and definition of concepts describing person–environment relationships. Disability and Rehabilitation, 25(2), 57–66.

Kempen, G. I., Ranchor, A. V., Ormel, J., Sonderen, E. V., Jaarsveld, C. H. V., & Sanderman, R. (2005). Perceived control and long-term changes in disability in late middle-aged and older persons: An 8-year follow-up study. Psychology and Health, 20(2), 193–206.

Kylén, M., Ekström, H., Haak, M., Elmståhl, S., & Iwarsson, S. (2014). Home and health in the third age—Methodological background and descriptive findings. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(7), 7060–7080.

Kylén, M., Schmidt, S. M., Iwarsson, S., Haak, M., & Ekström, H. (2017). Perceived home is associated with psychological well-being in a cohort aged 67–70 years. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 51, 239–247.

Lachman, M. E. (1986). Locus of control in aging research: A case for multidimensional and domain-specific assessment. Psychology and Aging, 1(1), 34.

Lagergren, M., Fratiglioni, L., Hallberg, I. R., Berglund, J., Elmståhl, S., Hagberg, B., et al. (2004). A longitudinal study integrating population, care and social services data. The Swedish National study on Aging and Care (SNAC). Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 16(2), 158–168.

Lawton, M. P. (1986). Environment and aging. New York: Center for the Study of Aging.

Lawton, M. P., Nahemow, L., Eisdorfer C., & Lawton M. P. (1973). Ecology and the aging process. The psychology of adult development and aging (pp. 619–674). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association

MacKinnon, D. P., & Dwyer, J. H. (1993). Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluation Review, 17(2), 144–158.

Nyunt, M. S. Z., Lim, M. L., Yap, K. B., & Ng, T. P. (2012). Changes in depressive symptoms and functional disability among community-dwelling depressive older adults. International Psychogeriatrics, 24(10), 1633–1641.

Oswald, F., Wahl, H., Martin, M., & Mollenkopf, H. (2003). Toward measuring proactivity in person–environment transactions in late adulthood: The housing-related control beliefs questionnaire. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 17(1–2), 135–152.

Oswald, F., Wahl, H., Schilling, O., & Iwarsson, S. (2007). Housing-related control beliefs and independence in activities of daily living in very old age. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 14(1), 33–43.

Petrie, K. J., Cameron, L. D., Ellis, C. J., Buick, D., & Weinman, J. (2002). Changing illness perceptions after myocardial infarction: An early intervention randomized controlled trial. Psychosomatic Medicine, 64(4), 580–586.

Preacher, K. J., & Kelley, K. (2011). Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychological Methods, 16(2), 93.

Schulz, R., & Heckhausen, J. (1999). Aging, culture and control: Setting a new research agenda. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 54(3), P13–P145.

Sonn, U., & Asberg, K. H. (1991). Assessment of activities of daily living in the elderly. A study of a population of 76-year-olds in Gothenburg, Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 23(4), 193–202.

Tennstedt, S., Howland, J., Lachman, M., Peterson, E., Kasten, L., & Jette, A. (1998). A randomized, controlled trial of a group intervention to reduce fear of falling and associated activity restriction in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 53(6), P38–P392.

Tomsone, S., Horstmann, V., Oswald, F., & Iwarsson, S. (2013). Aspects of housing and perceived health among ADL independent and ADL dependent groups of older people in three national samples. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 25(3), 317–328.

Wahl, H., Schilling, O., Oswald, F., & Iwarsson, S. (2009). The home environment and quality of life-related outcomes in advanced old age: Findings of the ENABLE-AGE project. European Journal of Ageing, 6(2), 101–111.

Wallston, K. A., Wallston, B. S., Smith, S., & Dobbins, C. J. (1987). Perceived control and health. Current Psychology, 6(1), 5–25.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Lund University. We would like to extend our thanks to all participants and to those who provided the administrative support.

Funding

The Home and Health in the Third Age Study was financed by the Swedish Research Council (521-2012-2809) and the Ribbingska Foundation in Lund, Sweden. This study was accomplished within the context of the Centre for Aging and Supportive Environments (CASE) at Lund University, Sweden, financed by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (FORTE) (2006-1613).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: GG, JB, SMS, BS, SI. Data analysis: GG. Interpretation of the results: GG, JB, SMS, BS, SI. Manuscript drafting: GG. Reviewing the manuscript for critical content: JB, SMS, BS, SI. Reviewing and approving the final version: GG, JB, SMS, BS, SI.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

SI and BS are the copyright holders and owners of the HE assessment tool and software, provided as commercial products. The other authors have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset generated and analysed during the current study is part of the The Swedish National Study on Ageing and Care and was used under a data use agreement and can therefore not be shared by the authors.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and informed consent to participate

SNAC-GÅS and the Home and Health in the Third Age Study were conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Ethical Board in Lund (2010/431, 2002-2012 LU 744-00). Informed consent was obtained from all participants and confidentiality was ensured.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gefenaite, G., Björk, J., Schmidt, S.M. et al. Associations among housing accessibility, housing-related control beliefs and independence in activities of daily living: a cross-sectional study among younger old in Sweden. J Hous and the Built Environ 35, 867–877 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-019-09717-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-019-09717-4