Abstract

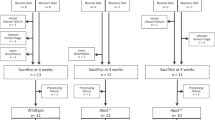

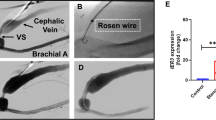

Intracoronary stenting is a common procedure in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD). Stent deployment stretches and denudes the endothelial layer, promoting a local inflammatory response, resulting in neointimal hyperplasia. Vitamin D deficiency associates with CAD. In this study, we examined the association of vitamin D status with high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1)-mediated pathways (HMGB1, receptor for advanced glycation end products [RAGE], and Toll-like receptor-2 and -4 [TLR2 and TLR4]) in neointimal hyperplasia in atherosclerotic swine following bare metal stenting. Yucatan microswine fed with a high-cholesterol diet were stratified to receive vitamin D-deficient (VD-DEF), vitamin D-sufficient (VD-SUF), and vitamin D-supplemented (VD-SUP) diet. After 6 months, PTCA (percutaneous transluminal balloon angioplasty) followed by bare metal stent implantation was performed in the left anterior descending (LAD) artery of each swine. Four months following coronary intervention, angiogram and optical coherence tomography (OCT) were performed and swine euthanized. Histology and immunohistochemistry were performed in excised LAD to evaluate the expression of HMGB1, RAGE, TLR2, and TLR4. OCT analysis revealed the greatest in-stent restenosis area in the LAD of VD-DEF compared to VD-SUF or VD-SUP swine. The protein expression of HMGB1, RAGE, TLR2, and TLR4 was significantly higher in the LAD of VD-DEF compared to VD-SUF or VD-SUP swine. Vitamin D deficiency was associated with both increased in-stent restenosis and increased HMGB1-mediated inflammation noted in coronary arteries following intravascular stenting. Inversely, vitamin D supplementation was associated with both a decrease in this inflammatory profile and in neointimal hyperplasia, warranting further investigation for vitamin D as a potential adjunct therapy following coronary intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Mathers CD, Loncar D (2006) Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 3:e442

Nobuyoshi M, Kimura T, Nosaka H, Mioka S, Ueno K, Yokoi H et al (1988) Restenosis after successful percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty: serial angiographic follow-up of 229 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 12:616–623

Rupprecht HJ, Brennecke R, Bernhard G, Erbel R, Pop T, Meyer J (1990) Analysis of risk factors for restenosis after PTCA. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 19:151–159

Buccheri D, Piraino D, Andolina G, Cortese B (2016) Understanding and managing in-stent restenosis: a review of clinical data, from pathogenesis to treatment. J Thorac Dis 8(10):E1150–E1162

Joner M, Finn AV, Farb A, Mont EK, Kolodgie FD, Ladich E et al (2006) Pathology of drug-eluting stents in humans: delayed healing and late thrombotic risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 48:193–202

Nebeker JR, Virmani R, Bennett CL, Hoffman JM, Samore MH, Alvarez J et al (2006) Hypersensitivity cases associated with drug-eluting coronary stents: a review of available cases from the Research on Adverse Drug Events and Reports (RADAR) project. J Am Coll Cardiol 47:175–181

Yoshida Y, Mitsumata M, Ling G et al (1997) Migration of medial smooth muscle cells to the intima after balloon injury. Atherosclerosis Ann N Y Acad Sci 8111:459–470

Collins MJ, Li X, Lv W et al (2012) Therapeutic strategies to combat neointimal hyperplasia in vascular grafts. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 10(5):635–647

Brennan A, Katz DR, Nunn JD, Barker S, Hewison M, Fraher LJ et al (1987) Dendritic cells from human tissues express receptors for the immunoregulatory vitamin D3 metabolite, dihydroxycholecalciferol. Immunology 61:457–461

Veldman CM, Cantorna MT, DeLuca HF (2000) Expression of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) receptor in the immune system. Arch Biochem Biophys 374:334–338

Lemire JM, Archer DC, Beck L, Spiegelberg HL (1708S) Immunosuppressive actions of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3: preferential inhibition of Th1 functions. J Nutric 125:1704S–1708S

Penna G, Adorini L (2000) 1 Alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits differentiation, maturation, activation, and survival of dendritic cells leading to impaired alloreactive T cell activation. J Immunol 164:2405–2411

Canning MO, Grotenhuis K, de Wit H, Ruwhof C, Drexhage HA (2001) 1-alpha,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)(2)D(3)) hampers the maturation of fully active immature dendritic cells from monocytes. Eur J Endocrinol 145:351–357

Chen S, Swier VJ, Boosani CS, Radwan MM, Agrawal DK (2016) Vitamin D deficiency accelerates coronary artery disease progression in swine. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 36(8):1651–1659

Gupta GK, Agrawal T, Del Core MG, Hunter WJ 3rd, Agrawal DK (2012) Decreased expression of vitamin D receptors in neointimal lesions following coronary artery angioplasty in atherosclerotic swine. PLoS ONE 7:e42789. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0042789

Gupta GK, Agrawal T, Rai V, Core MGD, Hunter WJ, Agrawal DK (2016) Vitamin D supplementation reduces intimal hyperplasia and restenosis following coronary intervention in atherosclerotic swine. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0156857

Holick MF (2007) Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med 357(3):266–281

Rai V, Agrawal DK (2017) Role of vitamin D in cardiovascular diseases. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am 46(4):1039–1059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2017.07.009

Daraghmeh AH, Bertoia ML, Al-Qadi MO, Abdulbaki AM, Roberts MB, Eaton CB (2016) Evidence for the vitamin D hypothesis: the NHANES III extended mortality follow-up. Atherosclerosis 255:96–101

Carbone F, Satta N, Burger F, Roth A, Lenglet S, Pagano S et al (2016) Vitamin D receptor is expressed within human carotid plaques and correlates with pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages. Vascul Pharmacol 85:57–65

Rai V, Agrawal DK (2017) The role of damage- and pathogen-associated molecular patterns in inflammation-mediated vulnerability of atherosclerotic plaques. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 95(10):1245–1253. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjpp-2016-0664

Su Z, Lu H, Jiang H et al (2015) IFN-γ-producing Th17 cells bias by HMGB1-T-bet/RUNX3 axis might contribute to progression of coronary artery atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 243(2):421–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.09.037

Jialal I, Rajamani U, Adams-Huet B, Kaur H (2014) Circulating pathogen associated molecular pattern—binding proteins and High Mobility Group Box protein 1 in nascent metabolic syndrome: Implications for cellular Toll-like receptor activity. Atherosclerosis 236(1):182–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.06.022

Cai J, Yuan H, Wang Q et al (2015) HMGB1-driven inflammation and intimal hyperplasia after arterial injury involves cell-specific actions mediated by TLR4. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 35(12):2579–2593. https://doi.org/10.1161/atvbaha.115.305789

Kouassi KT, Gunasekar P, Agrawal DK, Jadhav GP (2018) TREM-1; is it a pivotal target for cardiovascular diseases? J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 5(3):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd5030045

Bangert A, Andrassy M, Müller A-M et al (2015) Critical role of RAGE and HMGB1 in inflammatory heart disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1522288113

Kierdorf K, Fritz G (2013) RAGE regulation and signaling in inflammation and beyond. J Leukoc Biol 94(1):55–68. https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.1012519

Takeuchi M (2016) Serum Levels of Toxic AGEs (TAGE) may be a promising novel biomarker for the onset/progression of lifestyle-related diseases. Diagnostics 6(2):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics6020023

Xu L, Wang Y-R, Li P-C, Feng B (2016) Advanced glycation end products increase lipids accumulation in macrophages through upregulation of receptor of advanced glycation end products: increasing uptake, esterification and decreasing efflux of cholesterol. Lip Health Dis. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-016-0334-0

Heier M, Margeirsdottir HD, Gaarder M et al (2015) Soluble RAGE and atherosclerosis in youth with type 1 diabetes: a 5-year follow-up study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-015-0292-2

Nam M-H, Son W-R, Lee YS, Lee K-W (2015) Glycolaldehyde-derived advanced glycation end products (glycol-AGEs)-induced vascular smooth muscle cell dysfunction is regulated by the AGES-receptor (RAGE) axis in endothelium. Cell Commun Adhes 22(2–6):67–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/15419061.2016.1225196

Zhou Z, Wang K, Penn MS et al (2003) Receptor for AGE (RAGE) mediates neointimal formation in response to arterial injury. Circulation 107(17):2238–2243. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000063577.32819.23

Sakaguchi T, Yan SF, Yan SD et al (2003) Central role of RAGE-dependent neointimal expansion in arterial restenosis. J Clin Invest 111(7):959–972

Reitman JS, Mahley RW, Fry DL (1982) Yucatan miniature swine as a model for diet-induced atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 43:119–132

Schwartz RS, Murphy JG, Edwards WD, Camrud AR, Vliestra RE, Holmes DR (1990) Restenosis after balloon angioplasty. A practical proliferative model in porcine coronary arteries. Circulation 82:2190–2200

Inoue K, Kawahara K, Biswas KK, Ando K, Mitsudo K, Nobuyoshi M, Maruyama I (2007) HMGB1 expression by activated vascular smooth muscle cells in advanced human atherosclerosis plaques. Cardiovasc Pathol 16:136–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carpath.2006.11.006

Akira S, Takeda K, Kaisho T (2001) Toll-like receptors: critical proteins linking innate and acquired immunity. Nat Immunol 2:675–680. https://doi.org/10.1038/90609

Yang H, Antoine DJ, Andersson U, Tracey KJ (2013) The many faces of HMGB1: molecular structure-functional activity in inflammation, apoptosis, and chemotaxis. J Leukoc Biol 93:865–873. https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.1212662

Vink A, Schoneveld AH, van der Meer JJ, van Middelaar BJ, Sluijter JP, Smeets MB, Quax PH, Lim SK, Borst C, Pasterkamp G, de Kleijn DP (2002) In vivo evidence for a role of toll-like receptor 4 in the development of intimal lesions. Circulation 106:1985–1990

Rao Z, Zhang N, Xu N et al (2017) Front Immunol 8:1308. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01308

Chen S, Law CS, Gardner DG (2010) Vitamin D-dependent suppression of endothelin-induced vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation through inhibition of CDK2 activity. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 118(3):135–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.11.002

Li Q, Li J, Wen T et al (2014) Overexpression of HMGB1 in melanoma predicts patient survival and suppression of HMGB1 induces cell cycle arrest and senescence in association with p21 (Waf1/Cip1) up-regulation via a p53-independent, Sp1-dependent pathway. Oncotarget 5(15):6387–6403. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.2201

Zhang H, Yang N, Wang T, Dai B, Shang Y (2017) Vitamin D reduces inflammatory response in asthmatic mice through HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2017.8216

Higashi T, Sano H, Saishoji T et al (1997) The receptor for advanced glycation end products mediates the chemotaxis of rabbit smooth muscle cells. Diabetes 46:463–472

Sukino S, Kotani K, Nirengi S, Gugliucci A, Caccavello R, Tsuzaki K, Kawaguchi Y, Takahashi K, Egawa K, Shibata H, Yoshimura M, Kitagawa Y, Sakane N (2016) Dietary intake of Vitamin D is related to blood levels of advanced glycation end products during a weight loss program in obese women. J Biomed 1:1–4. https://doi.org/10.7150/jbm.16497

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by research Grants R01HL144125, R01HL116042 and R01HL120659 to DK Agrawal from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, USA. The content of this original research article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: DKA, MS, and PG; Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tool: DKA; Conducting Experiments, analysis and interpretation of the data: MS and PG; Drafting of the article: MS and PG; Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: MS, PG, JAA, and DKA; Final approval of the article: MS, PG, JAA, and DKA.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

Ethics approval

Creighton University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the animal research protocol (#0831.2).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Satish, M., Gunasekar, P., Asensio, J.A. et al. Vitamin D attenuates HMGB1-mediated neointimal hyperplasia after percutaneous coronary intervention in swine. Mol Cell Biochem 474, 219–228 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-020-03847-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-020-03847-y