Abstract

In many industrial processes, the climate-damaging gas CO2 is produced as undesired by-product. The dual fluidized bed biomass gasification technology offers the opportunity to tackle this problem by using the produced CO2 within the process as gasification agent. Therefore, a 100 kWth pilot plant at TU Wien was used to investigate the use of CO2 as gasification agent by converting softwood as fuel and olivine as bed material into high-valuable product gas. A parameter variation was conducted, where the typically used gasification agent steam was substituted stepwise by CO2. Thereby, the amount of CO and CO2 increased and the content of H2 decreased in the product gas. These trends resulted in a declining H2/CO ratio and a decreasing lower heating value when CO2 was increased as gasification agent. In contrast to these declining trends, the carbon utilization efficiency showed an increasing course. As second part of this work, a temperature variation from 740 to 840 °C was conducted to investigate the change of the main product gas components. With increasing temperature, CO and H2 increased and CO2 decreased. To determine the degree of conversion of CO2 in the DFB reactor system, two approaches were selected: (1) a carbon balance and (2) a hydrogen balance. This way, it was found out that a certain amount of CO2 was indeed converted at the investigated process conditions. Furthermore, under certain assumptions, the reverse water-gas shift reaction was identified to be the predominant reaction during CO2 gasification.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Starting from the Kyoto protocol [1], which was published in 1998, followed by the Renewable Energy Directive (RED) established in 2009 by the European Union up to the Paris Agreement from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 2015 [2], several approaches for CO2 mitigation were established in the past. It went further with a recast of the Renewable Energy Directive—Recast to 2030 (RED II) in December 2018 to strengthen the awareness of climate change and its possible effects on the environment and humanity [3]. To sum up, all these protocols and agreements urgently appeal to reduce CO2 emissions and to mitigate the negative effects of climate change worldwide.

Furthermore, the predicted increase of CO2 emissions up to 60% in 2050 compared with that in 2011 presents a driving force for the development and realization of renewable energy technologies [4]. Additionally, the reutilization of unavoidably produced CO2 and in parallel the conversion of CO2 into valuable products is urgent. A possible technology to tackle these problems could be the thermochemical conversion process of biomass through gasification. In this way, fossil energy sources like crude oil or lignite can be substituted by renewable, alternative feedstocks and CO2 used within the process as gasification agent. In this way, a high-valuable product gas can be generated, which can be further upgraded in different chemical synthesis steps to produce advanced biofuels [5, 6] or other chemicals [7]. For this purpose, the dual fluidized bed (DFB) biomass gasification process, which was developed at TU Wien, could serve as a key technology. Successful test runs with steam as gasification agent have been carried out for more than 20 years [8]. However, the use of CO2 as gasification agent presents a novel research topic. First experimental test runs using mixtures of steam and CO2 were already carried out, starting in 2018 [9, 10]. The main findings of these test runs were:

-

In contrast to pure steam biomass gasification, where a hydrogen (H2)–rich product gas is generated, a carbon monoxide (CO)–rich product gas is created, when CO2 is used as gasification agent.

-

The H2/CO ratio, which presents an important factor for different downstream synthesis processes, decreased, when a higher content of CO2 was used in the gasification agent mixture.

-

The utilization of CO2 as gasification agent showed an increase in the carbon utilization efficiency.

-

Through the supplementing properties of steam and CO2 as gasification agent, lower tar contents were generated compared with pure steam gasification.

Other research groups like CEA in France [11], Jeremias et al. [12,13,14] in the Czech Republic, Stec et al. [15] in Poland, Cheng et al. [16] in Singapore, and Szul et al. [17] from the Institute of Chemical Processing of Coal (IChPW) in Poland also already examined the use of CO2 as gasification in fluidized bed reactor systems. The main outcomes of their works comply with the findings of the first experimental test runs in the DFB reactor system. The H2/CO ratio was reduced [11], mixtures of steam and CO2 had a positive effect on tar reduction [12], the CO2/C ratio influenced the CO yield [15], and the cold gas efficiency increased, when CO2 was used as gasification agent [14].

The use of pure CO2 as gasification was not investigated in the DFB reactor system during the first experimental test runs so far. Therefore, this missing building block was investigated within the scope of this publication. The influence of the stepwise substitution of steam by CO2 as gasification up to 100 vol.-% on the H2/CO ratio, the CO2 conversion, the carbon utilization efficiency, and the cold gas efficiency was examined. Furthermore, a temperature variation from about 740 to about 840 °C was carried out under pure CO2 atmosphere to determine the influence on the product gas quality. As a concluding chapter, investigations regarding the determination of the conversion of CO2 within the DFB reactor system are presented. For this purpose, carbon and hydrogen balances were set up around the gasification reactor for pure CO2 gasification and compared with a pure steam gasification test run.

2 Materials and methods

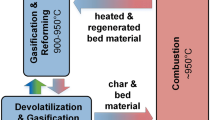

For the experimental test runs, a 100 kWth DFB pilot plant, which was built at TU Wien, was used. The principle of the DFB gasification pilot plant is shown in Fig. 1. The pilot plant is composed of two reactors: a gasification reactor (GR, blue rectangle) and a combustion reactor (CR, red rectangle), which are connected by loop seals (horizontal arrows). The GR is divided into a lower part, where the devolatilization and gasification reactions take place and an upper part, where reforming and tar cracking reactions occur. The GR can be fluidized with CO2 and/or steam and mixtures thereof and the CR is fluidized with air. Biomass is introduced into the lower part of the GR. In the GR, a product gas, which is composed of carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen (H2), carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), ethylene (C2H4), water (H2O), and other minor components, is generated. In the CR, a flue gas, which mainly contains CO2, H2O, nitrogen (N2), and oxygen (O2), is produced.

The 100 kWth DFB biomass gasification pilot plant went into operation in 2014 at TU Wien [18]. Fig. 2 shows the upper part of the pilot plant with three fuel hoppers and the lower part of the reactor system with some ash removal containers. The GR of the pilot plant is operated as a bubbling fluidized bed in the lower part and as a counter-current column with turbulent fluidized bed zones in the upper part. In the upper part of the gasification reactor, also constrictions are installed. These constrictions enable an increased interaction of downward flowing hot bed material particles with upward streaming product gas. In this way, the contact time as well as the conversion efficiency can be increased [19, 20]. A more detailed description of the pilot plant and the corresponding measurement equipment can be found in literature [18, 21].

2.1 Relevant chemical reactions during biomass gasification

In Table 1, a selection of important heterogeneous gas-solid and homogeneous gas-gas reactions, which can occur during the DFB biomass gasification process, is presented. The gas-solid reactions are displayed in Eqs. 1–3 and the gas-gas reactions are stated in Eqs. 4–7. Gas-gas reactions are secondary gasification reactions, which occur between the gasification agent, the gaseous products of char gasification, and the gaseous products of pyrolysis.

2.2 Investigated materials

For the presented test runs, softwood (SW) pellets were used as fuel and olivine as bed material. The proximate and ultimate analyses of SW are shown in Table 2 and the composition of olivine is presented in Table 3. Olivine, which shows catalytically active behavior [23, 24], was used because it is known as state-of-the-art bed material and typically used in industrial-sized biomass gasification plants [25, 26].

2.3 Validation of process data with IPSE

The validation of the process data was carried out by the calculation of mass and energy balances with the software tool IPSEpro. In this way, data, which cannot be measured directly during experimental test runs, can be determined. For the simulation with IPSEpro, a detailed model library, which wasdel ccc.bat"developed at TU Wien over many years, was used [27, 28]. All experimental results presented within this publication were validated with IPSEpro. Based on the validated data, the following key figures were selected to describe the performance and efficiency of the presented test runs in detail. All input and output streams, which were used for the calculation of the performance indicating key figures, are presented in Fig. 3.

The CO2 to carbon ratio, φCO2C, presented in Eq. 8, is defined as the introduced CO2 as gasification agent to C in the dry and ash-free fuel. The product gas yield PGY describes the ratio between the volume flow of dry product gas to the mass flow of dry and ash-free fuel introduced into the GR (see Eq. 9). The carbon to CO conversion XC➔CO describes the amount of CO in the product gas to the total amount of introduced C as fuel and gasification agent (see Eq. 10). C in CO2 as gasification agent is calculated through the share named XC,CO2,fluid and the mass flow of CO2 as gasification agent. Eq. 11 shows the CO2 conversion rate XCO2, which gives the ratio of consumed CO2 during gasification to the amount of CO2 introduced into the GR via CO2 as gasification agent and CO2 produced from the pyrolysis of the fuel. Detailed information about the calculation of XCO2 can be found in [10]. XH2O is defined as the steam-related water conversion. It presents the water consumed for e.g. CO and H2 production in relation to the sum of water, which is fed to the GR as gasification agent and fuel water (see Eq. 12). The overall cold gas efficiency ηCG,o is presented in Eq. 13. It describes the amount of chemical energy in the product gas in relation to the chemical energy of the fuel introduced into the gasification and combustion reactor minus appearing heat losses. Due to the fact that the GR was fluidized with different ratios of CO2, the value ɸCO2 was introduced, which describes the share of CO2 used as gasification agent. The calculation of ɸCO2 is shown in Eq. 14. The carbon utilization efficiency (XC) (see Eq. 15) gives the ratio of the amount of carbon leaving the GR via the product gas minus the content of carbon in char and tar to the amount of carbon introduced into the GR with the fuel and CO2 as gasification agent.

The equation for calculating the deviation from the reverse water-gas shift reaction (RWGS), which is displayed in Eq. 4, is given in Eq. 16. The equilibrium constant Kp, RWGS(T) was calculated using the software tool HSC Chemistry [29]. If the deviation is zero, it means that the equilibrium state of the equation is reached. A negative value would indicate that the gas composition is on the side of the reactants, which would mean that a further reaction is thermodynamically possible. A positive sign would imply that the actual state is on the side of the products. However, this state cannot be reached thermodynamically through the RWGS reaction alone. Additional reactions are required as stated in [30]. In Eq. 17, the logarithmic deviation from the Boudouard (BOU) reaction (see Eq. 2) pδeq, BOU is shown. The equilibrium constant (Kp, BOU(T)) was calculated by the use of the software tool HSC [29] as well. When pδeq,BOU is 0, the Boudouard reaction is in equilibrium. When pδeq, BOU > 0, the state of equilibrium lies on the product side, whereas when pδeq, BOU < 0, the equilibrium is located on the reactants side.

In Eq. 18, the ratio between water in the fuel and steam introduced into the GR as gasification agent to the amount of C in the fuel and CO2 introduced into the GR as gasification agent is shown.

2.4 Thermodynamic calculations

To develop efficient biomass conversion technologies, which can also compete with fossil energy technologies, it is required to determine their energy efficiency. For the determination of the energy efficiency of different processes, various performance indicators, mostly based on thermodynamics, are used [31]. Due to that fact, thermodynamic calculations were carried out for the test runs carried out within the scope of this work as well and compared with the experimental results. In this way, a better understanding of the ongoing chemical reactions in the DFB reactor system could be gained and the energy efficiency of the process evaluated.

For the thermodynamic calculations, the product gas compositions at different shares of ɸCO2 and at different temperatures were calculated assuming thermodynamic equilibrium with the software tool HSC Chemistry [29]. HSC Chemistry uses the Gibbs free energy minimization method. In the equilibrium state, the Gibbs free energy is minimized. Detailed descriptions of this approach can be found in literature [32, 33].

As already mentioned beforehand, the product gas of the DFB reactor system is mainly composed of CO, H2, CO2, CH4, H2O, and higher hydrocarbons. Higher hydrocarbons with the formula CxHy were summarized by the compound C2H4. Based on these chemical compounds, the following simultaneous chemical gas-gas reactions were taken into account to take place in the DFB reactor system during the presented gasification test run:

-

the water-gas shift reaction (Eq. 4),

-

the methanation reaction (Eq. 5),

-

the steam reforming reaction (Eq. 6),

-

and the dry reforming reaction (Eq. 7).

The results of the thermodynamic calculations are presented in the results section and compared with the experimental results of the test runs.

3 Results and discussion

In this chapter, the main findings of experimental test runs are presented. The results of the stepwise substitution of steam by CO2, the temperature variation under pure CO2 atmosphere as well as the carbon and hydrogen balances are shown.

3.1 From pure steam to pure CO2 as gasification agent

In Table 4, the main operational parameters from five test runs for investigating the stepwise substitution of steam by CO2 are shown. Softwood pellets were used as fuel and olivine as a bed material for all test runs. ɸCO2 was changed from 0 to 1. The fuel power introduced into the GR (PGR) was in a range of 83 to 95 kW. The amount of additional fuel, which was introduced into the CR (PCR) to control the gasification temperature and to compensate for the relatively high heat losses of the pilot plant, was between 59 and 68 kW. To enable a comparison of these test runs with test runs, where pure steam was used as gasification agent, a ratio between PCR and PGR was calculated. For pure steam gasification test runs, a PCR/PGR ratio of around 0.5 is a typical value, but it depends on the type of fuel introduced into the GR as well as the operating parameters [24, 34]. Test run 1 (pure steam) showed a quite high PCR/PGR compared with other pure steam gasification test runs in literature. However, this outlier can be explained by the relatively high heat losses for this test run. Taking into account a typical PCR/PGR ratio for pure steam gasification of around 0.5, it can be seen that adding CO2 to the gasification agent resulted in a higher PCR/PGR ratio. This phenomenon can be declared by the fact that CO2 gasification, where the RWGS and the Boudouard reaction are predominated to take place, required more heat and therefore a higher input of additional fuel into the CR was required. Similar findings can be found in literature [15, 35].

The CO2 to carbon ratio increased with an increasing value of ɸCO2 and therefore an increasing amount of CO2 introduced into the GR as gasification agent. The temperatures in the gasification and the combustion reactors were in the same range for all test runs (830–840 °C). In the following, the experimental results are presented. To compare the experimental results with theory, the thermodynamic calculations explained above were used.

Figure 4 shows the course of the main product gas components based on the data of Fig. 5 in the thermodynamic equilibrium depending on the gasification agent. In the thermodynamic equilibrium, the H2 content decreased and the CO content increased. The CO2 content showed an increasing trend as well. The water content was quite stable between ɸCO2 of 0 and 0.68 but decreased for ɸCO2 of 1.

Figure 5 presents the experimental results of the 5 test runs with increasing ɸCO2. CO2 and CO showed an increasing trend with increasing ɸCO2. The opposite phenomenon was seen for H2, which was decreasing with increasing CO2 input. CH4 slightly declined but remained relatively stable. However, this declining trend could also be an effect of dilution by CO2. The water content showed a decreasing trend as well, which can also be seen for the thermodynamic calculations. The trends of the experimental results were in accordance with the trends of the thermodynamic calculations, however, there are high deviations in the amounts of the product gas components. This indicates that it was experimentally not possible to produce this thermodynamically possible product gas composition in the DFB reactor system. Nevertheless, the thermodynamic calculations provide a good insight into the theoretically possible limits.

Figure 6 shows the deviation from the equilibrium of the RWGS reaction with increasing ɸCO2. Findings in literature showed that the deviation of the equilibrium of the RWGS lies on the side of the products between 827 and 838 °C in the thermodynamic equilibrium [37]. This was also the case for pure steam as gasification agent and when CO2 was added as gasification agent. When ɸCO2 approaches 1 (100 vol% CO2), the gas composition was completely on the side of the educts, which was explained by the high amount of CO2 in the product gas for pure CO2 gasification. A certain amount of CO2 was not converted during the gasification process, which diluted the product gas.

To sum up, kinetic effects like a too low contact time between gas and particles could explain the huge deviation from the thermodynamic equilibrium and the high content of CO2 in the product gas when using pure CO2 as gasification. It is well known that the reaction rate of the Boudouard reaction is much slower than the reaction rate of the RWGS reaction [38]. Longer contact times between gas and particles would improve the conversion efficiency as stated in literature [39]. Additionally, higher temperatures, especially in the lower gasification reactor (T GRlower) would have also been favorable for the progress of the mentioned chemical reactions and thus the conversion efficiency. This assumption was also proven in literature by Sadhwani et al. [36]. If higher temperatures would be reached in the gasification reactor, the conversion efficiency of CO2 via the RWGS and Boudouard reactions could be enhanced and the deviation from the RWGS equilibrium reduced. In contrast to that, when steam and CO2 were used as gasification agents (test runs 2, 3, and 4), the applied temperatures were sufficient and the deviations from the chemical equilibrium were close to zero.

Table 5 shows the performance indicating key figures of validated data with IPSEpro. The CO2 conversion rate is at maximum for the pure CO2 gasification test run. The water conversion decreased. This could be explained by the RWGS reaction, where H2O was formed (see Eq. 4 in the opposite direction) at temperatures over 800 °C. The carbon to CO conversion XC➔CO is at maximum, when the GR was fluidized with pure CO2. An increase in the carbon utilization efficiency XC with increasing CO2 as gasification agent was visible. Overall, cold gas efficiencies around 70% were reached for all test runs. The H2/CO ratio was lowered from 1.49 for ɸCO2 = 0 to 0.36 for ɸCO2 = 1. The same declining trend was seen for the lower heating value (LHV), which could be explained by the increasing amount of CO2 in the product gas. The gravimetric tar content of pure steam and pure CO2 gasification was higher than the one, which was produced when a value of ɸCO2 of 0.68 was applied as gasification agent. This could be explained by the combined effect of steam and dry reforming reactions [9, 12]. The dust contents were in the range of 0.3 to 1.0 g/m3stp and are typical values for the gasification with olivine as bed material [21, 24]. The char contents were lower, when CO2 was present as gasification agent and higher when only steam was used as gasification agent. This could be explained by a higher amount of fuel, which was introduced into the CR for test run 1.

3.2 Temperature variation under pure CO2 atmosphere

A temperature variation from 740 to 840 °C with pure CO2 as gasification agent was conducted. Additionally, the main product gas components based on data of Fig. 8 in the thermodynamic equilibrium depending on the gasification temperature are displayed in Fig. 7. In the thermodynamic equilibrium, CO contents between 39 and 53 vol.-%db were possible, while the amount of CO2 ranged between 24 and 38 vol.-%db. The H2 content was around 22 vol.-%db and the CH4 content was practically zero. The water content decreased from about 14 to 10 vol.-%.

Figure 8 shows the experimental results of the temperature variation when a value of ɸCO2 of 1 was used as gasification agent. The trends of CO2 and CO of the thermodynamic calculations were equal to that of the experimental results; however, the amounts showed quite high deviations. The CO content showed an increase from 23 to 38 vol%db and the CO2 content a decrease from 58 to 39 vol%db in the experimental investigations. In contrast to the quite constant trend of H2 in the thermodynamic calculations for an increasing gasification temperature, the experimental results showed an increasing course of H2. CH4 remained relatively stable with increasing temperature but was almost completely converted in the thermodynamic calculations. The water content showed a decreasing trend for the experimental results and the thermodynamic calculations. In general, there are deviations in the amounts of the product gas components between the thermodynamic calculations and the experimental results, but the trends of CO, CO2, H2O, and CH4 of the thermodynamic calculations corresponded to the trends of the experimental investigations.

Based on the trends of CO and CO2 in Fig. 8, one can conclude that higher temperatures, over 840 °C, would be favorable for using pure CO2 as gasification agent. At higher temperatures, the RWGS reaction as well as the Boudouard reaction, which both favor the production of CO, would take place to a higher extent (see [37, 39]).

Figure 9 depicts the deviation from the RWGS and the Boudouard reaction equilibrium calculated with Eqs. 16 and 17 of the different operating points of the temperature variation displayed in Fig. 8. It is obvious that the deviation from the Boudouard equilibrium was much higher than the deviation from the RWGS equilibrium over the whole temperature range. This points out that the RWGS reaction could be the predominant reaction during the temperature variation. However, further experiments at higher gasification temperatures are recommended to investigate this assumption in more detail.

In Fig. 10, the correlations between the CO2 conversion, the carbon utilization efficiency, and the overall cold gas efficiency over the increasing gasification temperature during pure CO2 gasification are shown. With increasing gasification temperature, the CO2 conversion, the carbon utilization efficiency, and the overall cold gas efficiency increased. This indicated again that higher gasification temperatures would be favorable for utilizing and in parallel converting CO2 within the DFB reactor system, because an increasing trend of these key figures can be foreseen.

3.3 Two approaches to determine the conversion of CO2 during biomass gasification

Due to the reason that it is very difficult to measure the exact conversion of CO2 during the gasification process in the DFB reactor system, two approaches were investigated and established:

-

a carbon balance around the gasification reactor

-

and a hydrogen balance around the gasification reactor.

The main material streams around the GR for the carbon and the hydrogen balances are shown in Fig. 11.

3.3.1 Carbon balance

The first approach to investigate the CO2 conversion during the DFB biomass gasification process was carried out through setting up a carbon balance around the GR. This was carried out for pure steam gasification with ɸCO2 = 0 and values of ɸCO2 of 0.68 and 1, which means pure CO2 gasification. The carbon balances are shown in Fig. 12. Softwood was used as fuel and olivine as a bed material for all three cases. For the test run with ɸCO2 = 0 (pure steam gasification), it was assumed that the whole amount of CO2 in the product gas was produced from C in the fuel (biomass). This resulted in a value of about 2.6 kg/h C in CO2 of the product gas, which was formed from 9.4 kg/h of C in the fuel. However, for the runs with ɸCO2 = 0.68 and 1, two sources of CO2 in the product gas were possible: (1) carbon in the fuel (C in fuel) and (2) carbon in CO2 as gasification agent (C in CO2 agent) (see Fig. 12).

Therefore, this stream was calculated (a) based on data with ɸCO2 = 0 (labeled with a number sign) and (b) based on data of pyrolysis experiments from Neves et al. [40] (labeled with an asterisk). They investigated the production of the pyrolysis gas based on more than 60 different types of biomasses regarding the amount and the composition of the pyrolysis gas depending on the temperature. For the calculation based on data with ɸCO2 = 0, about 2.4 kg/h “CCO2 of C in fuel” and 2.5 kg/h “CCO2 of CO2 agent” for the test run with ɸCO2 of 0.68 were generated. For the other case, experimental data of pyrolysis were used for the calculation. This resulted in an amount of 0.9 kg/h “CCO2 of C in fuel”. Through the subtraction of 0.9 kg/h “CCO2 of C in fuel” from the total amount of 4.9 kg/h “C in CO2” in the product gas, a value of 4.0 kg/h “CCO2 of CO2 agent” was obtained. The amount of “CCO2 of C in fuel” ranged between 0.9 and 2.4 kg/h and the amount of “CCO2 of CO2 agent” laid in a range of 2.5–4.0 kg/h.

For the gasification test run with ɸCO2 = 1, about 2.4 kg/h “CCO2 of C in fuel” and 4.4 kg/h “CCO2 of CO2 agent” were produced, calculated based on the reference steam gasification test run. The calculation based on pyrolysis data showed that about 0.9 kg/h “CCO2 of C in fuel” from 6.8 kg/h “C in CO2” of the PG was generated for the gasification with ɸCO2 of 1. To sum up, the carbon balances around the GR present the first approach to determine the amount, of how much C of CO2 in the PG originates from C of CO2 as gasification agent and how much originates from C in the fuel.

3.3.2 Hydrogen balance

The second approach to investigate the CO2 conversion during the gasification process was conducted by establishing hydrogen balances around the GR. Based on the experimental results presented above, it can be concluded that the RWGS plays a crucial role during CO2 gasification. The same is also stated in literature, that the WGS or RWGS reaction acts as a central part during CO2 gasification [11, 13, 41]. To examine this topic in more detail, hydrogen balances were set up around the GR for a pure steam gasification test run as a reference case and for CO2 gasification test runs with ɸCO2 of 0.68 and 1 (see Fig. 13).

H in the fuel (H in fuel), H in H2O in the fuel (HH2O in fuel), and H in steam as gasification agent (H in steam) were regarded as input streams. H in H2O in the product gas (H in H2O), H in H2 in the product gas (H in H2), H in higher hydrocarbons in the product gas (H in CxHy), H in tar and char in the product gas (H in tar and char), and H transported to the CR via char together with the bed material (H to CR) were considered as output streams. For the interpretation of the H balances, only the WGS reaction was taken into account. It was assumed that when H in H2O in the product gas was lower than the sum of HH2O in fuel and HH2O in steam, the introduced water into the GR was consumed to produce H2. This would indicate that the WGS reaction took place. For the reference case with ɸCO2 = 0 displayed in Fig. 13, the sum of H in steam and HH2O in fuel was higher than the amount of H in H2O in the PG. Thus, the WGS reaction took place.

For the test run with ɸCO2 of 0.68, H in H2O was higher than the sum of HH2O in fuel and HH2O in steam. This means that water was produced during the gasification process. Hence, the RWGS reaction was the predominant reaction for this case. The same result was found for ɸCO2 = 1. H in H2O was higher than the sum of HH2O in fuel and HH2O in steam, which also points out that the RWGS reaction proceeded during the gasification process predominantly.

In summary, carbon balances around the GR were established as a first approach to determine the amount of CO2, which is converted during the gasification process. Based on the results shown in Fig. 12, it can be concluded that a certain amount of CO2 was converted. Based on the data of the reference test run with pure steam (ɸCO2 = 0), it was possible to convert about 26% of C in the fuel to C in CO2 in the product gas. The rest, 72% of C in the fuel, was converted to other products like CO, CxHy, tar, and char. For the test runs with ɸCO2 of 0.68 and 1, C in CO2 in the product gas also originated to a certain part from C in CO2 as gasification agent. For ɸCO2 of 0.68, between 15% (asterisk sign means pyrolysis data) and 47% (number sign means reference steam gasification test run) of C in CO2 as gasification was converted to other product gas components, except CO2. For the test run with ɸCO2 of 1, which means pure CO2 gasification, it was possible to convert between 26% (asterisk sign means pyrolysis data) and 45% (number sign means reference steam gasification test run) of C in CO2 as gasification agent to other product gas components like CO, CxHy, tar, or char.

To sum up, these two approaches present a first way to investigate the conversion efficiency as well as the predominant reaction during CO2 gasification under past assumptions. It was found out that CO2 is indeed converted in the DFB reactor system to a certain extent and that the RWGS seems to be the predominant reaction, which occurs when using CO2 as gasification agent.

4 Conclusions and outlook

In the scope of this publication, the influence of the stepwise substitution of steam by CO2 as gasification was investigated. Additionally, a temperature variation from about 740 to about 840 °C was carried out under a pure CO2 atmosphere. To give an overview of the main findings of the performed test runs and investigations, the obtained results can be summarized as follows.

-

By substituting steam by CO2, the product gas was shifted towards higher CO and lower H2 contents. Using pure CO2 as gasification agent shows already promising results between 827 and 838 °C. With an increase in CO2 as gasification agent, an increase in the production of CO, an increase of the carbon utilization efficiency, and an increase of the overall cold gas efficiency was observed.

-

The temperature variation indicated that higher temperatures, over 840 °C, would be favorable for pure CO2 gasification. At higher temperatures, the RWGS reaction as well as the Boudouard reaction could take place to a higher extent. With an increase of the gasification temperature, the CO2 conversion, the carbon utilization efficiency, and the overall cold gas efficiency could be improved. Thus, an increase of the gasification temperature over 840 °C presents a promising approach to convert a higher amount of CO2 in the DFB reactor system.

-

The carbon balances revealed that between 26% (asterisk sign means pyrolysis data) and 45% (number sign reference steam gasification test run) of C in CO2 as gasification agent was converted to other product gas components except CO2. This implies that CO2 was indeed utilized in the DFB reactor system at the investigated process conditions. Additionally, the results of the hydrogen balances and that of Fig. 9 indicated that the RWGS reaction might be the predominant reaction during CO2 gasification at the investigated operation conditions. In general, it must be noted that the findings of the carbon and hydrogen balances are based on certain assumptions. Therefore, further research regarding these investigations is recommended.

Concluding from all these results, the gasification temperature seems to be the crucial parameter during CO2 gasification in the DFB reactor system. Future research should focus on investigations at higher temperatures, over 840 °C, in the DFB reactor system to strengthen the outcomes of the carried out investigations.

Abbreviations

- CBP:

-

Carbon boundary point

- CR:

-

Combustion reactor

- DFB:

-

Dual fluidized bed

- GC/MS:

-

Gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry

- GR:

-

Gasification reactor

- Grav. tar:

-

Gravimetric tar

- IChPW:

-

Institute of Chemical Processing of Coal

- LHV:

-

Lower heating value

- PGY:

-

Product gas yield

- RED:

-

Renewable energy directive

- RWGS:

-

Reverse water-gas shift

- SW:

-

Softwood

- Vol.-%:

-

Volumetric percent

- WGS:

-

Water-gas shift

- Wt.-%:

-

Weight percent

- C:

-

Carbon

- CR:

-

Combustion reactor

- Daf:

-

Dry and ash-free

- Db:

-

Dry basis

- Fuel:

-

Fuel to gasification reactor

- GR:

-

Gasification reactor

- H2O:

-

Water

- PG:

-

Product gas

- Stp:

-

Standard temperature and pressure

- Th:

-

Thermal

- x, y :

-

Stoichiometric factors (-)

- ṁ :

-

Mass flow (kg/s)

- X :

-

Mass fraction, volume fraction (-)

- k CO2 :

-

Conversion factor of C to CO2 of fuel introduced into GR (-)

- V̇ PG :

-

Dry volumetric product gas flow (m3/s)

- X CO2 :

-

CO2 conversion (kgCO2/kgCO2)

- X C :

-

Carbon utilization efficiency (%)

- X C➔CO :

-

C to CO conversion (kgC,CO/kgC,fuel&fluid)

- φ CO2C :

-

CO2 to carbon ratio (kgCO2/kgC)

- η CG,o :

-

Overall cold gas efficiency (%)

- Q̇ loss :

-

Heat loss (kW)

- LHV:

-

Lower heating value (MJ/kg)

- PGY:

-

Product gas yield (m3stp,db/kgfuel,daf)

- P CR/P GR ratio:

-

Ratio of power introduced into CR to power introduced into GR (-)

- H2/CO ratio:

-

Ratio of H2 to CO of product gas (-)

- ɸ CO2 :

-

Share of CO2 used as gasification agent

- pδeq, WGS :

-

Deviation from water-gas shift equilibrium (-)

- K p(T):

-

Equilibrium constant of specific chemical reaction depending on temperature

- p i :

-

Partial pressure of component i

- ν i :

-

Stoichiometric factor of component i

- pδ eq, BOU :

-

Deviation from Boudouard equilibrium (-)

References

United Nations. (1998) Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations framework convention on climate change 20

UNFCCC. (2015) Adoption of the Paris Agreement: proposal by the President to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change 21932:1–32

Eropean Union. 2019 https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/jec/renewable-energy-recast-2030-red-ii Accessed 1 Jan 2019

Gironès VC, Moret S, Peduzzi E, Nasato M, Maréchal F (2017) Optimal use of biomass in large-scale energy systems: insights for energy policy. Energy 137:789–797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2017.05.027

Weber G (2017) Production of mixed alcohols using MoS2 catalyst from biomass derived synthesis gas. Doctoral thesis, TU Wien

Gruber H, Groß P, Rauch R, Weber G, Loipersböck J, Niel J, et al. (2017) Fischer-tropsch Synthesis – effects of feedstock load changes regarding product quality and catalyst attrition. Proc. 25th Eur. Biomass Conf. Exhib. Stock. Sweden, https://doi.org/10.5071/25thEUBCE2017-3AO.9.4

Breit B, Almena J, Riermeier T, Wienand W, Beller M (2007) Katalytische Carbonylierung zur Herstellung von Fein- chemikalien und Pharmazeutika: Katalysatoren. Verfahren und Produkte Chemie Ing Tech 79:1288–1288. https://doi.org/10.1002/cite.200750089

Hofbauer H (2017) Biomass gasification for electricity and fuels, large scale. Encycl. Sustain. Sci. Technol., Springer, 459–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5820-3

Mauerhofer AM, Fuchs J, Müller S, Benedikt F, Schmid JC, Hofbauer H (2019) CO2 gasification in a dual fluidized bed reactor system: impact on the product gas composition. Fuel 253:1605–1616

Mauerhofer AM, Müller S, Benedikt F, Fuchs J, Bartik A, Hofbauer H (2019) CO2 gasification of biogenic fuels in a dual fluidized bed reactor system. Biomass Convers Biorefinery. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-019-00493-3

Valin S, Bedel L, Guillaudeau J, Thiery S, Ravel S (2016) CO2 as a substitute of steam or inert transport gas in a fluidised bed for biomass gasification. Fuel 177:288–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2016.03.020

Jeremiáš M, Pohořelý M, Svoboda K, Manovic V, Anthony EJ, Skoblia S, Beňo Z, Šyc M (2017) Gasification of biomass with CO2 and H2O mixtures in a catalytic fluidised bed. Fuel 210:605–610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2017.09.006

Jeremiáš M, Pohořelý M, Svoboda K, Skoblia S, Beňo Z, Šyc M (2018) CO2 gasification of biomass: the effect of lime concentration in a fluidised bed. Appl Energy 217:361–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.02.151

Pohořelý M, Jeremiáš M, Svoboda K, Kameníková P, Skoblia S, Beňo Z (2014) CO2 as moderator for biomass gasification. Fuel 117:198–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2013.09.068

Stec M, Czaplicki A, Tomaszewicz G, Słowik K (2018) Effect of CO2 addition on lignite gasification in a CFB reactor: a pilot-scale study. Korean J Chem Eng 35:129–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11814-017-0275-y

Cheng Y, Thow Z, Wang CH (2016) Biomass gasification with CO2 in a fluidized bed. Powder Technol 296:87–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2014.12.041

Szul M, Słowik K, Głód K, Iluk T. 2019 Influence of pressure and CO2 in fluidized bed gasification of waste biomasses. Proc. Int. Conf. Polygeneration Strateg., . doi:ISBN: 978–3–9503671-1-9

Schmid JC. 2014 Development of a novel dual fluidized bed gasification system for increased fuel flexibility. TU Wien, doctoral thesis

Schmid JC, Pröll T, Kitzler H, Pfeifer C, Hofbauer H (2012) Cold flow model investigations of the countercurrent flow of a dual circulating fluidized bed gasifier. Biomass Convers Biorefinery 2:229–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-012-0035-5

Mauerhofer AM, Schmid JC, Benedikt F, Fuchs J, Müller S, Hofbauer H (2019) Dual fluidized bed steam gasification: change of product gas quality along the reactor height. Energy 173:1256–1272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2019.02.025

Schmid JC, Benedikt F, Fuchs J, Mauerhofer AM, Müller S, Hofbauer H (2019) Syngas for biorefineries from thermochemical gasification of lignocellulosic fuels and residues - 5 years’ experience with an advanced dual fluidized bed gasifier design. Biomass Convers Biorefinery. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-019-00486-2 REVIEW ARTICLE Syngas

Kaltschmitt M, Hartmann H, Hofbauer H. 2016 Energie aus Biomasse. 2. Auflage. Springer

Koppatz S, Pfeifer C, Hofbauer H (2011) Comparison of the performance behaviour of silica sand and olivine in a dual fluidised bed reactor system for steam gasification of biomass at pilot plant scale. Chem Eng J 175:468–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2011.09.071

Mauerhofer AM, Benedikt F, Schmid JC, Fuchs J, Müller S, Hofbauer H (2018) Influence of different bed material mixtures on dual fluidized bed steam gasification. Energy 157:957–968. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2018.05.158

Benedikt F, Kuba M, Christian J, Müller S, Hofbauer H (2020) Assessment of correlations between tar and product gas composition in dual fluidized bed steam gasification for online tar prediction. Appl Energy 238:1138–1149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.01.181

Kirnbauer F, Hofbauer H (2013) The mechanism of bed material coating in dual fluidized bed biomass steam gasification plants and its impact on plant optimization. Powder Technol 245:94–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2013.04.022

Müller S, Fuchs J, Schmid JC, Benedikt F, Hofbauer H (2017) Experimental development of sorption enhanced reforming by the use of an advanced gasification test plant. Int J Hydrog Energy 42:29697–29707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.10.119

Pröll T, Hofbauer H (2008) Development and application of a simulation tool for biomass gasification based processes. Int J Chem React Eng 6:A89. https://doi.org/10.2202/1542-6580.1769

Outokumpu HSC 2002 Chemistry thermochemical database. Version 6.1 A Roine - Finland: Outokumpu Research Oy

Kuba M, Kirnbauer F, Hofbauer H (2017) Influence of coated olivine on the conversion of intermediate products from decomposition of biomass tars during gasification. Biomass Convers Biorefinery 7:11–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-016-0204-z

Ptasinski KJ (2008) Thermodynamic efficiency of biomass gasification and biofuels conversion. Biofuels Bioprod Biorefin 2:239–253. https://doi.org/10.1002/bbb

Bartik A, Benedikt F, Lunzer A, Walcher C, Müller S, Hofbauer H. (2019) Thermodynamic investigation of SNG production based on dual fluidized bed gasification of biogenic residues. Int. Conf. Polygeneration Strateg. Vienna, p. 4

Jarungthammachote S, Dutta A (2008) Equilibrium modeling of gasification: Gibbs free energy minimization approach and its application to spouted bed and spout-fluid bed gasifiers. Energy Convers Manag 49:1345–1356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2008.01.006

Benedikt F, Schmid JC, Fuchs J, Mauerhofer AM, Müller S, Hofbauer H (2018) Fuel flexible gasification with an advanced 100 kW dual fluidized bed steam gasification pilot plant. Energy 164:329–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2018.08.146

Renganathan T, Yadav MV, Pushpavanam S, Voolapalli RK, Cho YS (2012) CO2 utilization for gasification of carbonaceous feedstocks: a thermodynamic analysis. Chem Eng Sci 83:159–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2012.04.024

Sadhwani N, Adhikari S, Eden MR (2016) Biomass gasification using carbon dioxide: effect of temperature, CO2/C ratio, and the study of reactions influencing the process. Ind Eng Chem Res 55:2883–2891. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.5b04000

Poboß N (2016) Experimentelle Untersuchung der sorptionsunterstützten Reformierung. Universität Stuttgart, Docotral thesis

Ahmed II, Gupta AK (2011) Kinetics of woodchips char gasification with steam and carbon dioxide. Appl Energy 88:1613–1619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2010.11.007

Lahijani P, Alimuddin Z, Mohammadi M, Rahman A (2015) Conversion of the greenhouse gas CO2 to the fuel gas CO via the Boudouard reaction: a review. Renew Sust Energ Rev 41:615–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.08.034

Neves D, Thunman H, Matos A, Tarelho L, Gómez-Barea A (2011) Characterization and prediction of biomass pyrolysis products. Prog Energy Combust Sci 37:611–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecs.2011.01.001

Kamenikova P, Pohorely M, Skoblia S, Vosecky M, 2008 Puncochar M. Deliverable D 5.1 Report on results of fundamental studies on steam gasification

Funding

Open access funding provided by TU Wien (TUW). This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 764675.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mauerhofer, A.M., Müller, S., Bartik, A. et al. Conversion of CO2 during the DFB biomass gasification process. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 11, 15–27 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-020-00822-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-020-00822-x