Abstract

Purpose of Review

Managed retreats are an important climate change adaptation tool. They seek the relocation of communities due to perceptions that they are already exposed to undue levels of risk or will become exposed to high risk in the near future because of climate change. Here, we focus on the economics of managed retreats and specifically focus on the question of who pays or may pay for these relocations.

Recent Findings

There is a significant body of research in the other social sciences (political science, sociology, anthropology, history) on managed retreats, but almost none in economics. No paper that we are aware has focused primarily on the question of who pays for managed retreats, and the survey here therefore focusses on lessons we can learn from examples, specifically an example from New Zealand and from the little references to these questions in the existing literature.

Summary

Sources of funding for managed retreats can come from the affected communities, from the public sector (the government or public insurers), and from the private sector (mostly private insurers). It is politically easier to implement managed retreats if it is the latter groups (public and private insurers) that pay, rather than placing the burden on the general taxpayer or on the affected communities themselves.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Mandatory and often heavy-handed relocations are not that unusual in more authoritarian countries; the biggest one may have been the relocations of more than a million people upstream on the Yangtse River ahead of the construction of the Three Gorges Dam. In the USA, FEMA has long been authorized to buy out high-risk properties and has bought approximately 40,000 properties distributed in numerous communities in 44 states in the past three decades. In its most well-publicized (and well-researched) program, in NY and NJ after Hurricane Sandy in 2012, FEMA acquired about 300 houses, out of about 10,000 that were damaged [17]. Japan has relocated tens of thousands of people from the coast following the March 2011 tsunami (the Great East Japan Earthquake); these were mostly people whose houses were destroyed (see Pinter et al. [18]).

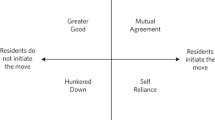

Braamskamp and Penning-Rowsell [19] observe that rare sudden-onset events, as those characterizing the risks in Quadrants A and C, might also be necessary to generate the political support for a managed retreat programme, especially if that programme requires public funding. Generating public support for retreats due to more predictable and frequent risks is more difficult. The objections to funding retreat for frequent (i.e. widely expected) risks is that the owners ‘should have known better’ than to purchase assets/homes in harm’s way. In any case, these political considerations are not our focus here.

The choice of 2007, several years before the earthquake, was deliberate. Assessments of property values, required for the collection of property taxes, are done in New Zealand every 3 years. In principle, the 2010 values could have been used. However, the property market in New Zealand, as elsewhere, experienced a decline after the global financial crisis which started in September 2008. The government wanted to use a value that will not reflect that (possibly temporary/cyclical) dip in prices and therefore made its offers based on pre-crisis values.

The local authorities (Christchurch city council) intended to disconnect basic services (water, sewage, and electricity) to these remaining properties to incentivize their cooperation in the voluntary RRZ programme, but the council received legal advice that disconnecting might be illegal [29].

This is an estimated figure, rather than an accurate one. The public insurer initially assessed and recorded the damage cost for each individual property affected by the earthquakes. We aggregate these initial estimates for the RRZ’s properties, but in many cases, initial estimates undervalued the damage.

I am grateful to Cuong Nguyen for pointing to some cases that exhibit these problems.

References

Nalau J, Handmer J. Improving development outcomes and reducing disaster risk through planned community relocation. Sustainability. 2018;10(10):3545.

Noy I. To leave or not to leave? Climate change, exit, and voice on a Pacific Island. CESifo Economic Studies. 2017;63(4):403–20.

Mortreux C, Safra de Campos R, Adger N, Ghosh T, Das S, Adams H, et al. Political economy of planned relocation: a model of action and inaction in government responses. Glob Environ Chang. 2018;50:123–32.

Crepelle A. The United States first climate relocation: recognition, relocation, and indigenous rights at the isle de Jean Charles. Belmont Law Review. 2018;6:1–40.

Beine M, Parsons C. Climatic factors as determinants of international migration. Scand J Econ. 2015;117(2):723–67.

Beine M, Noy I, Parson C. Climate change, migration and voice: an explanation for the immobility paradox. IZA Discussion paper. 2019; 12640.

Desmet K, Nagy DK, & Rossi-Hansberg E. The geography of development: evaluating migration restrictions and coastal flooding. NBER Working Paper 21087; 2015

Drabo A, Mbaye L. Natural disasters, migration and education: an empirical analysis in developing countries. Environ Dev Econ. 2015;20(6):767–96.

Hsiang SM, Sobel AH. Potentially extreme population displacement and concentration in the tropics under non-extreme warming. Sci Rep. 2016;6.

Hino M, Field CB, Mach KJ. Managed retreat as a response to natural hazard risk. Nat Clim Chang. 2017a;7:364–70.

Gibbs MT. Why is coastal retreat so hard to implement? Understanding the political risk of coastal adaptation pathways. Ocean Coast Manag. 2016;130:107–14.

Ajibade I. Planned retreat in global south megacities: disentangling policy, practice, and environmental justice. Clim Chang. 2019;157:299–317.

Marino E. Adaptation privilege and voluntary buyouts: perspectives on ethnocentrism in sea level rise relocation and retreat policies in the US. Glob Environ Chang. 2018;49:10–3.

Siders AR. Social justice implications of US managed retreat buyout programs. Clim Chang. 2019;152:239–57.

Bukvic A, Zhu H, Lavoie R, Becker A. The role of proximity to waterfront in residents' relocation decision-making post-hurricane Sandy. Ocean Coast Manag. 2018;154:8–19.

Rulleau B, Rey-Valette H, Clement V, et al. Impact of justice and solidarity variables on the acceptability of managed realignment. Clim Pol. 2017;17(3):361–77.

Siders A. Past US floods give lessons in retreat. Nature. 2017;548:281.

Pinter N, Ishiwateri M, Nonoguchi A, et al. Large-scale managed retreat and structural protection following the 2011 Japan tsunami. Nat Hazards. 2019;96:1429–36.

Braamskamp A, Penning-Rowsell E. Managed retreat: a rare and paradoxical success, but yielding a dismal prognosis. Environmental Management and Sustainable Development. 2018;7(2):108–36.

Frame DJ, Wehner MF, Rosier SM and Noy I (2020). The Climate-Change-Attributable Economic Costs of Hurricane Harvey. (in press)

Craig RK. Coastal adaptation, government-subsidized insurance, and perverse incentives to stay. Clim Chang. 2019;152:215–26.

Holub M, Fuchs S. Mitigating mountain hazards in Austria – legislation, risk transfer, and awareness building. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci. 2009;9:523–37.

Rauter M, Schindelegger A, Fuchs S, Thaler T. Deconstructing the legal framework for flood protection in Austria: individual and state responsibilities from a planning perspective. Water Int. 2019;44(5):571–87.

Kusuma A, Nguyen C, & Noy I. “Insurance for catastrophes: why are natural hazards underinsured, and does it matter?” in: Okuyama and rose (eds.) Advances in Spatial and Economic Modeling of Disaster Impacts. Springer, 2019; pp. 43-70.

Saunders WSA and Becker JS. A discussion of resilience and sustainability: Land use planning recovery from the Canterbury earthquake sequence, New Zealand. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2015;14:73–81.

McDonald M, Carlton S. Staying in the red zones - monitoring human rights in the Canterbury earthquake recovery. Christchurch: New Zealand Human Rights Commission; 2016.

Nguyen C. Homeowners’ choice when the government proposes a managed retreat. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, forthcoming. 2020

Hoang T & Noy I. Wellbeing after a managed retreat: observations from a large New Zealand program. CESifo Working paper 7938. 2019

Grierson S (2014) Legal obligations to provide infrastructure to the residential red zone. Document Obtained from Christchurch City Council under the Official Information Act.

Thaler T, Fuchs S. Financial recovery schemes in Austria: how planned relocation is used as an answer to future flood events. Environ Hazards. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/17477891.2019.1665982.

Hino M, Field CB, & Mach KJ (2017b). Supplementary information: managed retreat as a response to natural hazard risk. Nature Climate Change. https://media.nature.com/original/nature-assets-draft/nclimate/journal/v7/n5/extref/nclimate3252-s1.pdf

Klein N. The shock doctrine: the rise of disaster capitalism. Macmillan. 2008

Kousky C. Managing shoreline retreat: a US perspective. Clim Chang. 2014;124:9–20.

Owen S and Noy I. Regressivity in Public Natural Hazard Insurance: A Quantitative Analysis of the New Zealand Case. Economics of Disasters and Climate Change. 2019;3:235–55.

Funding

The author thanks the Resilience National Science Challenge for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Progress in the Solution Space of Climate Adaptation

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Noy, I. Paying a Price of Climate Change: Who Pays for Managed Retreats?. Curr Clim Change Rep 6, 17–23 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-020-00155-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-020-00155-x