Abstract

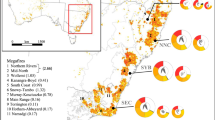

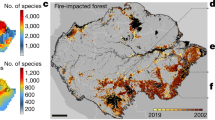

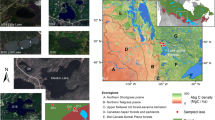

Australia’s 2019–2020 mega-fires were exacerbated by drought, anthropogenic climate change and existing land-use management. Here, using a combination of remotely sensed data and species distribution models, we found these fires burnt ~97,000 km2 of vegetation across southern and eastern Australia, which is considered habitat for 832 species of native vertebrate fauna. Seventy taxa had a substantial proportion (>30%) of habitat impacted; 21 of these were already listed as threatened with extinction. To avoid further species declines, Australia must urgently reassess the extinction vulnerability of fire-impacted species and assist the recovery of populations in both burnt and unburnt areas. Population recovery requires multipronged strategies aimed at ameliorating current and fire-induced threats, including proactively protecting unburnt habitats.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All datasets used in this analysis are available via the citations identified in the Methods. The raw data used to create Figs. 1 and 2 are available in Supplementary Table 1 and in figshare with the identifier https://figshare.com/s/62ef92b49704bb139333.

Code availability

The code used in this study is freely available at https://figshare.com/s/d9140d7c22e5ebbf2e03.

Change history

10 August 2020

The Data availability and Code availability statements have been amended to update the links where the data and code are deposited, respectively. The second sentence of the Data availability statement now reads: ‘The raw data used to create Figs. 1 and 2 are available in Supplementary Table 1 and in figshare with the identifier https://figshare.com/s/62ef92b49704bb139333.’ The Code availability statement now reads ‘The code used in this study is freely available at https://figshare.com/s/d9140d7c22e5ebbf2e03.’

References

Bowman, D. et al. Fire in the Earth system. Science 324, 481–484 (2009).

Mangel, M. & Tier, C. Four facts every conservation biologist should know about persistence. Ecology 75, 607–614 (1994).

Gill, A. M. Fire and the Australian flora: a review. Aust. For. 38, 4–25 (1975).

Brotons, L., Herrando, S. & Pons, P. Wildfires and the expansion of threatened farmland birds: the ortolan bunting Emberiza hortulana in Mediterranean landscapes. J. Appl. Ecol. 45, 1059–1066 (2008).

Bird, R. B., Tayor, N., Codding, B. F. & Bird, D. W. Niche construction and Dreaming logic: Aboriginal patch mosaic burning and varanid lizards (Varanus gouldii) in Australia. Proc. Biol. Sci. 280, 20132297 (2013).

Bowman, D. M. J. S., Wood, S. W., Neyland, D., Sanders, G. J. & Prior, L. D. Contracting Tasmanian montane grasslands within a forest matrix is consistent with cessation of Aboriginal fire management. Austral Ecol. 38, 627–638 (2013).

Lindenmayer, D. B., Kooyman, R. M., Taylor, C., Ward, M. & Watson, J. E. M. Recent Australian wildfires made worse by logging and associated forest management. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 898–900 (2020).

Jolly, W. M. et al. Climate-induced variations in global wildfire danger from 1979 to 2013. Nat. Commun. 6, 7537 (2015).

Murphy, B. P. & Russell-Smith, J. Fire severity in a northern Australian savanna landscape: the importance of time since previous fire. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 19, 46–51 (2010).

Mantgem, P. J. et al. Climatic stress increases forest fire severity across the western United States. Ecol. Lett. 16, 1151–1156 (2013).

Fonseca, M. G. et al. Climatic and anthropogenic drivers of northern Amazon fires during the 2015-2016 El Nino event. Ecol. Appl. 27, 2514–2527 (2017).

Huge Wildfires in Russia’s Siberian Province Continue (NASA, 2019).

Escobar, H. Amazon fires clearly linked to deforestation, scientists say. Science 365, 853 (2019).

2018 Incident Archive Report (California Government, 2019).

Dennis, R., Hoffmann, A., Applegate, G., von Gemmingen, G. & Kartawinata, K. Large-scale fire: creator and destroyer of secondary forests in western Indonesia. J. Trop. Sci. 13, 786–799 (2001).

Verhegghen, A. et al. The potential of sentinel satellites for burnt area mapping and monitoring in the Congo Basin forests. Remote Sens. 8, 986 (2016).

Boer, M. M., Resco de Dios, V. & Bradstock, R. A. Unprecedented burn area of Australian mega forest fires. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 171–172 (2020).

Borunda, A. See how much of the Amazon is burning, how it compares to other years. National Geographic (29 August 2019).

Nolan, R. H. et al. Causes and consequences of eastern Australia’s 2019–20 season of mega-fires. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 1039–1041 (2020).

Kooyman, R. M., Watson, J. & Wilf, P. Gondwana World Heritage Site burns. Science 367, 1083 (2020).

Kelly, L. T., Bennett, A. F., Clarke, M. F. & Mccarthy, M. A. Optimal fire histories for biodiversity conservation. Conserv. Biol. 29, 473–481 (2015).

Davis, R. et al. Conserving long unburnt vegetation is important for bird species, guilds and diversity. Biodivers. Conserv. 25, 2709–2722 (2016).

Doherty, T. S., Davis, R. A., van Etten, E. J. B., Collier, N. & Krawiec, J. Response of a shrubland mammal and reptile community to a history of landscape-scale wildfire. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 24, 534–543 (2015).

Dixon, K. M., Cary, G. J., Worboys, G. L. & Gibbons, P. The disproportionate importance of long-unburned forests and woodlands for reptiles. Ecol. Evol. 8, 10952–10963 (2018).

Taylor, R. S. et al. Landscape‐scale effects of fire on bird assemblages: does pyrodiversity beget biodiversity? Divers. Distrib. 18, 519–529 (2012).

Lindenmayer, D. B. et al. Fire severity and landscape context effects on arboreal marsupials. Biol. Conserv. 167, 137–148 (2013).

Chia, E. K. et al. Effects of the fire regime on mammal occurrence after wildfire: site effects vs landscape context in fire-prone forests. Ecol. Manag. 363, 130–139 (2016).

Leahy, L. et al. Amplified predation after fire suppresses rodent populations in Australia’s tropical savannas. Wildl. Res. 42, 705–716 (2015).

Murphy, S. A. & Legge, S. M. The gradual loss and episodic creation of palm cockatoo (Probosciger aterrimus) nest-trees in a fire- and cyclone-prone habitat. Emu 107, 1–6 (2007).

Lyon, J. P. & O’Connor, J. P. Smoke on the water: can riverine fish populations recover following a catastrophic fire-related sediment slug? Austral Ecol. 33, 794–806 (2008).

Haslem, A. et al. Time-since-fire and inter-fire interval influence hollow availability for fauna in a fire-prone system. Biol. Conserv. 152, 212–221 (2012).

Kearney, S. et al. The threats to Australia’s imperilled species and implications for a national conservation response. Pac. Conserv. Biol. 25, 231–244 (2018).

Ward, M. S. et al. Lots of loss with little scrutiny: the attrition of habitat critical for threatened species in Australia. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 1, e117 (2019).

Species of National Environmental Significance (Commonwealth of Australia, 2019).

National Indicative Aggregated Fire Extent Dataset Version 20200225 (Commonwealth of Australia, 2020); https://go.nature.com/38wZSRr

Graham, E. M. et al. Climate change and biodiversity in Australia: a systematic modelling approach to nationwide species distributions. Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 26, 112–123 (2019).

Hoskin, C., Grigg, G., Stewart, D. & Macdonald, S. Frogs of Australia (James Cook University, 2015).

Tingley, R. et al. Geographic and taxonomic patterns of extinction risk in Australian squamates. Biol. Conserv. 238, 108203 (2019).

Guidelines for Assessing the Conservation Status of Native Species According to the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 and Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Regulations 2000 (Commonwealth of Australia, 2000).

Rapid Analysis of Impacts of the 2019–20 Fires on Animal Species, and Prioritisation of Species for Management Response – Preliminary Report (Commonwealth of Australia, 2020).

Brodribb, T. J., Powers, J., Cochard, H. & Choat, B. Hanging by a thread? Forests and drought. Science 368, 261–266 (2020).

Scheele, B. C. et al. Continental-scale assessment reveals inadequate monitoring for threatened vertebrates in a megadiverse country. Biol. Conserv. 235, 273–278 (2019).

Victoria’s Bushfire Emergency: Biodiversity Response and Recovery (Victoria State Government, 2020).

Smales, I., Brown, P., Menkhorst, P., Holdsworth, M. & Holz, P. Contribution of captive management of orange-bellied parrots to the recovery programme for the species in Australia. Int. Zoo. Yearb. 37, 171–178 (2000).

Broughton, S. K. & Dickman, C. R. The effect of supplementary food on home range of the southern brown bandicoot, Isoodon obesulus. Aust. J. Ecol. 16, 71–78 (1991).

Legge, S., Kennedy, M. S., Lloyd, R., Murphy, S. A. & Fisher, A. Rapid recovery of mammal fauna in the central Kimberley, northern Australia, following the removal of introduced herbivores. Austral Ecol. 36, 791–799 (2011).

IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) (WMO, 2018).

Clarke, H. & Evans, J. P. Exploring the future change space for fire weather in southeast Australia. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 136, 513–527 (2019).

Dowdy, A. J. et al. Future changes in extreme weather and pyroconvection risk factors for Australian wildfires. Sci. Rep. 9, 10073 (2019).

Taylor, C., Mccarthy, M. A. & Lindenmayer, D. B. Nonlinear effects of stand age on fire severity. Conserv. Lett. 7, 355–370 (2014).

Zylstra, P. J. Flammability dynamics in the Australian Alps. Austral Ecol. 43, 578–591 (2018).

Woinarski, J. C. Z., Burbidge, A. A. & Harrison, P. L. Ongoing unraveling of a continental fauna: decline and extinction of Australian mammals since European settlement. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 4531–4540 (2015).

Woinarski, J. C. Z. et al. Reading the black book: the number, timing, distribution and causes of listed extinctions in Australia. Biol. Conserv. 239, 108261 (2019).

Lindenmayer, D. B., Hunter, M. L., Burton, P. J. & Gibbons, P. Effects of logging on fire regimes in moist forests. Conserv. Lett. 2, 271–277 (2009).

Berry, Z. C., Wevill, K. & Curran, T. J. The invasive weed Lantana camara increases fire risk in dry rainforest by altering fuel beds. Weed Res. 51, 525–533 (2011).

McAlpine, C. A. et al. A continent under stress: interactions, feedbacks and risks associated with impact of modified land cover on Australia’s climate. Glob. Change Biol. 15, 2206–2223 (2009).

Dale, V. H. et al. Climate Change and forest disturbances. BioScience 51, 723–734 (2001).

Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia (IBRA) Version 7 (Subregions) (Commonwealth of Australia, 2018); https://go.nature.com/3e6j21L

Lobo, J. M., Jiménez‐Valverde, A. & Real, R. AUC: a misleading measure of the performance of predictive distribution models. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 17, 145–151 (2008).

Reside, A. E., Watson, I., Vanderwal, J. & Kutt, A. S. Incorporating low-resolution historic species location data decreases performance of distribution models. Ecol. Model. 222, 3444–3448 (2011).

Phillips, S. J., Anderson, R. P. & Schapire, R. E. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Model. 190, 231–259 (2006).

Fenner, A. L. & Bull, C. M. Short-term impact of grassland fire on the endangered pygmy bluetongue lizard. J. Zool. 272, 444–450 (2007).

Kuchling, G. Impact of fuel reduction burns and wildfires on the critically endangered western swamp tortoise Peudemydura umbrina. In Ecological Society of Australia Conference Proceedings (2007).

Driscoll, D. A. & Dale Roberts, J. Impact of fuel-reduction burning on the frog Geocrinia lutea in southwest Western Australia. Austral Ecol. 22, 334–339 (1997).

Smith, A., Meulders, B., Bull, C. M. & Driscoll, D. Wildfire-induced mortality of Australian reptiles. Herpetol. Notes 5, 233–235 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Legge and C. Pavey for their critical comments on an early version of the manuscript and the Commonwealth Government for providing both species and fire datasets. A.I.T.T. is supported by an ARC DECRA Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.E.M.W. conceived the idea. M.W., J.E.M.W., A.I.T.T., J.Q.R., B.A.W., A.E.R., S.L.M., H.J.M., M.M., H.P.P., S.J.V., J.L.O., E.J.M., A.C.G. and L.J.S. designed the research. A.E.R. and S.L.M. extracted non-threatened species data. M.W. and B.A.W. assembled and revised the database and analysed the data. M.W., A.I.T.T., J.Q.R., B.A.W., A.E.R., S.L.M., H.J.M., M.M., H.P.P., S.J.V., J.L.O., E.J.M., A.C.G., J.C.Z.W., S.T.G., M.L., B.C.S., J.C., D.G.N., D.B.L., R.M.K., J.S.S., L.J.S. and J.E.M.W. wrote and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table 1

This file contains all taxa impacted by the 2019–2020 mega-fires, including their approximate habitat loss, approximate proportional habitat loss and approximate habitat remaining.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ward, M., Tulloch, A.I.T., Radford, J.Q. et al. Impact of 2019–2020 mega-fires on Australian fauna habitat. Nat Ecol Evol 4, 1321–1326 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1251-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1251-1

This article is cited by

-

Long-term land transformation alters potential ecological corridors and increases functional connectivity cost among nature reserves in Guangdong, China

Landscape and Ecological Engineering (2024)

-

Mammal responses to global changes in human activity vary by trophic group and landscape

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2024)

-

First close insight into global daily gapless 1 km PM2.5 pollution, variability, and health impact

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Conservation genomics of an endangered arboreal mammal following the 2019–2020 Australian megafire

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Outcomes for an arboreal folivore after rehabilitation and implications for management

Scientific Reports (2023)