Abstract

The One Health approach has gained support across a range of disciplines; however, training opportunities for professionals seeking to operationalize the interdisciplinary approach are limited. Academic institutions, through the development of high-quality, experiential training programs that focus on the application of professional competencies, can increase accessibility to One Health education. The Rx One Health Summer Institute, jointly led by US and East African partners, provides a model for such a program. In 2017, 21 participants representing five countries completed the Rx One Health program in East Africa. Participants worked collaboratively with communities neighboring wildlife areas to better understand issues impacting human and animal health and welfare, livelihoods, and conservation. One Health topics were explored through community engagement and role-playing exercises, field-based health surveillance activities, laboratories, and discussions with local experts. Educational assessments reflected improvements in participants’ ability to apply the One Health approach to health and disease problem solving, as well as anticipate cross-sectoral challenges to its implementation. The experiential learning method, specifically the opportunity to engage with local communities, proved to be impactful on participants’ cultural awareness. The Rx One Health Summer Institute training model may provide an effective and implementable strategy by which to contribute to the development of a global One Health workforce.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the next decade, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that encompass social development (e.g., poverty), the environment (e.g., climate change), and economic progress (e.g., infrastructure) are positioned to set the agenda for global health; these goals embody a One Health (OH) strategy (Gostin and Friedman 2015). Implementing an OH approach to problem solving at the interface of people, animals, plants, and ecosystems increasingly demands knowledge, skills, and expertise from diverse disciplines and requires discipline-based experts to work collaboratively (Nyatanyi et al. 2017).

Universities are uniquely positioned to translate OH from concept into action through collaborative training; however, disciplinary inertia, crowded curricula, time constraints that vary by professional training program, and lack of funding for curriculum development and delivery often serve as barriers to progress (Barrett et al. 2011). Furthermore, evidence suggests that training programs that focus on application of concepts, rather than simply theoretical knowledge, are more successful for professional development (Vink et al. 2013).

For veterinary students, a number of experiential short courses have been developed to expand their knowledge, skills, and mentors in OH topic areas, such as AQUAVET®, MARVET, CONSERVET, and the Envirovet Summer Institute which ran from 1991 to 2010 (Conrad et al. 2009; Gilardi et al. 2004; Schwind et al. 2016). In medical schools, international clinical rotations have been associated with a deeper appreciation for global public health issues and cross-cultural competencies; yet still relatively few (24%) US medical students participate in global health experiences, and this number has been on the decline (Drain et al. 2007; AAMC 2019). There remains a scarcity of meaningful international opportunities and even fewer comprehensive OH training opportunities (Davis et al. 2017; Mazet et al. 2006; Reid et al. 2016; Rwego et al. 2016; Sikkema and Koopmans 2016; Wu et al. 2016). Few training programs in the USA or around the world offer capacity strengthening programs that are truly interdisciplinary, especially in “hotspot” regions for emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases like East and Central Africa (Amuguni et al. 2017).

High-quality, experiential training programs that focus on the application of professional competencies and provide a forum for dynamic, collaborative problem solving with diverse participants can build key skills for global health practitioners. The Rx One Health Summer Institute provides a model for such a program. The main goal of Rx One Health is to provide a “prescription” for addressing OH problems, enabling participants to enter global health careers with a more integrated, collaborative perspective. The program is coordinated by the University of California, Davis, in the USA and Sokoine University of Agriculture in Tanzania and involves other partners in East Africa. The curriculum emphasizes the core OH competency domains (Frankson et al. 2016): transdisciplinary collaboration, leadership, discovery, innovation, problem solving, communication, professionalism, diplomacy, teamwork, systems thinking, and cultural capacity strengthening (not only addressing the culture of local communities but recognizing the cultural components of one’s own professions).

Herein, we provide an overview of the Rx One Health program approach and development (i.e., steps taken to create a professionally relevant experiential program in OH for adult learners) and describe the inaugural course (2017) with an evaluation of the impact of the course on participants’ OH competencies. Educational assessments were conducted as part of the curriculum and are reported here for quality improvement and program evaluation purposes.

Methods

Curriculum Design and Development

Rx One Health Summer Institute was grounded in the pedagogical framework of a competency-based curriculum. Schools of medicine, public health, and veterinary medicine have been actively moving to competency-based educational models, and this paradigm is particularly relevant for collaborative problem solving and critical reasoning (Frenk et al. 2010). Overall Rx One Health program goals included enabling participants to:

-

1.

Describe how an OH approach can be operationalized to respond to complex health problems;

-

2.

Discuss OH problems from a transdisciplinary perspective;

-

3.

Describe methods to implement and evaluate OH approaches to address common problems;

-

4.

Facilitate effective communication, collaboration, and collegiality among participants with different professional and cultural backgrounds;

-

5.

Strengthen professional networks across health disciplines;

-

6.

Design, monitor, and evaluate OH research and community engagement; and

-

7.

Identify social, ecological, and economic barriers that might impact an OH approach.

Aligned with these goals, instructors developed learning experiences using the backward design method (Wiggins and McTighe 2005). This three-step process involved identifying desired competencies, determining acceptable evidence of learning, and planning learning experiences and instruction. Competencies were developed within five curriculum thematic areas which encompassed technical (e.g., outbreak investigation) and cross-cutting (e.g., communication, leadership) OH domains: (1) OH Foundations; (2) Zoonotic Disease; (3) Wildlife Health and Stakeholder Engagement; (4) Research Methods and Education; and (5) OH Policy, Systems, and Solutions (Table 1). Given the experiential nature of the curriculum, authentic assessment (i.e., demonstration of real-world tasks) was primarily used to provide evidence of learning. As such, learning experiences were designed to provide participants with opportunities to practice and demonstrate skills.

Program Leadership and Faculty

Rx One Health facilitators and instructors came from Tanzanian and Rwandan academic institutions (Sokoine University of Agriculture, University of Rwanda), governmental (e.g., Tanzania National Parks) and non-governmental organizations (e.g., Ifakara Health Institute, Gorilla Doctors), as well as University of California Davis’ Schools of Veterinary Medicine (SVM) and Medicine (SOM). Instructors represented diverse fields, including agriculture, environmental policy, veterinary medicine, human medicine, and conservation and were selected based on their subject matter expertise and alignment with program goals. Prior to developing their learning experiences, all instructors received a training handbook which outlined course goals, learning theory, tools for effective facilitation, and student biographies to improve the integration of learning objectives and engagement of learners in the community.

Program Organization and Implementation

Pre-immersion Preparation

Rx One Health participants independently completed a series of preparatory readings, tutorials, and assessments that enabled instructors to assess their capabilities prior to the in-country sessions (USAID PREDICT 2018). Additionally, participants received a global travel guide that provided country-specific recommendations for cultural sensitivity, health, and safety/security. Materials were available electronically via a secure, cloud-based file-sharing platform. Participants also had the opportunity to participate in synchronous Web-based group video conferencing to discuss travel logistics and ethical considerations for short-term international experiences with instructors as well as to facilitate communication among participants prior to arrival in country.

In-Country Sessions

The in-country program was divided into two sessions: Session 1 (Tanzania) and Session 2 (Rwanda). Each session spanned 2 weeks and presented OH challenges, stakeholders, and solutions within the context of the local setting. In each session, the curriculum focused on multiple thematic areas and learning objectives therein (Table 1). Learning objectives and associated competencies addressed disciplinary and technical health knowledge, social/cultural/historical perspectives of complex and emerging health problems, as well as cross-cutting professional characteristics (e.g., communication, ethics, and diplomacy). The program aimed to build these competencies through an increasingly learner-centered curriculum.

Session 1 (June 4–18), held in Tanzania (Dar es Salaam, Iringa, Ruaha National Park, Morogoro, and Bagamoyo), focused on OH foundations (e.g., interest-based problem solving that uses a process of consensus to find solutions that meet the needs of all parties); health monitoring of livestock and free-ranging wildlife; stakeholder engagement to understand health and economic challenges of local communities; and methods in environmental, infectious disease, and community-based research. Learning experiences included classroom-based discussions, hands-on field exercises (e.g., bat and rodent trapping and sampling), tours and demonstrations (e.g., sample processing and diagnostics), and small group problem solving and role playing (e.g., disease outbreak investigation simulation) which continually reinforced communication, organization, collaboration, and conflict resolution skills. Examples of learning experiences and the location of field exercises are provided in Table 1.

Session 2 (June 19–30), held in Rwanda (Kigali and Kinigi), continued to emphasize OH foundations, cultural capacity building, leadership skills, human healthcare delivery, and communication with an emphasis on stakeholder engagement. Additionally, this session introduced the concepts of community health, human resource capacity building, food safety, commercial animal agriculture, and public health (e.g., human causes of morbidity and mortality and opportunities for intervention) in preparation for a capstone immersion exercise. This exercise challenged participants to actively acquire on-site information from local stakeholders on OH challenges (e.g., child nutrition, community health challenges, livestock welfare and production, wildlife conflict, economic deprivations) to develop creative and integrative solutions to address some of these challenges. Participants worked together to develop and deliver an oral presentation to propose their OH solutions to a group of governmental and non-governmental stakeholders who provided feedback and discussed the intricate barriers and existing opportunities for implementing proposed solutions.

Program Evaluation

Qualitative Assessment

At the start of the in-country session, each participant proposed “Professional Responsibilities for OH Practitioners” (pre) to outline their ideas for core competencies for OH professionals. Responsibilities were updated as the course progressed, and at the end of the program, participants submitted their modified ideas (post) for discussion. Pre- and post-program responsibilities were transcribed, and responses were analyzed inductively using the constant comparison method (Dye et al. 2000) to determine how participants’ understanding of OH competencies changed after completing the course. Participant responses which represented key themes were selected for inclusion in the manuscript. A word cloud generator (TagCrowd.com) was also used to determine and compare the frequency of terms.

Quantitative Assessment

A pre-/post-self-efficacy assessment, administered at the end of the in-country session, compared participants’ perception of their own growth in understanding and abilities related to Rx One Health competencies before (pre) and after (post) the program. Assessments included nine paired questions each with five response categories ranging from “Poor” to “Excellent.” This retrospective format, where before and after information is collected concurrently, was chosen to reduce response-shift bias, a source of contamination of self-report measures that often results in overestimation of pretest scores (Raidl et al. 2004).

Descriptive statistics, including frequency, median, and range, were used to describe participant demographics. Mean, standard deviation, and paired t-tests were used to compare mean scores for each objective (9) on self-efficacy assessments. All quantitative analyses were conducted using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), and a P value of ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Demographics of Participant Cohort

Rx One Health Summer Institute 2017 provided training to 21 (10 males, 11 females) participants. Five countries were represented, including the USA (n = 11), Rwanda (n = 5), Tanzania (n = 3), Denmark (n = 1), and Nepal (n = 1). The median age of participants was 26 (min = 23, max = 54). The participants were early career professionals and students representing the fields of veterinary medicine, biological sciences, natural resources management, public health, human medicine, agricultural development, and community development.

Qualitative: “Professional Responsibilities for OH Practitioners”

At the start of the training course, participants more frequently emphasized their individual knowledge and skills to solve problems affecting humans, animals, and the environment. At the conclusion, participants more often expressed OH competencies in terms of generating collaboration and communication across multiple disciplines and with communities (Table 2). Before the training, participants described OH challenges from a narrow, disease-centric perspective, particularly zoonotic diseases. At the conclusion, participants described OH challenges more broadly, emphasizing such challenges as human–wildlife conflict, human and animal welfare and well-being, and ecosystem health. When cultivating solutions to these challenges, participants emphasized sustainability, respect, interdisciplinarity, and cultural sensitivity.

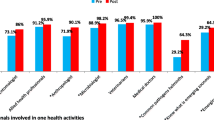

Quantitative: Pre-/Post-Self-Efficacy Assessment

Participant self-efficacy showed statistically significant improvements across all measured competencies. Those that resulted in the greatest difference between pre-training and post-training were: (1) understanding challenges to the implementation of the OH approach and (2) understanding community-based research and engagement within an OH framework. Complete results are provided in Table 3.

Discussion

The development and evaluation of the Rx One Health Summer Institute, described within, provides an example by which to produce a multi-institutional, interprofessional, experiential training program grounded in the core competencies of OH education. Learning assessments provided support of enhanced participant understanding and ability with regard to research and evaluation methods, particularly at the community level. Assessments also suggested an evolution of thought regarding OH topics, including cultural competence and interdisciplinary collaboration. After the training, participants more readily expressed OH competencies in terms of generating collaboration and communication across multiple disciplines. In essence, participants became more aware of the need to build “essential networks” to create and sustain the human assets necessary to implement an OH community network.

There was also a clear broadening of participants’ definition of OH challenges and mechanisms by which to address them. There was a shift from a disease-centric perspective of OH challenges to one that more readily considered health in terms of the community—human, animal, ecosystem, and economic well-being. Given the origins of the OH concept in the management of shared disease threats to humans and animals (Zinsstag 2012), the emphasis on zoonotic diseases was not unexpected. However, the disciplinary diversity of the Rx One Health program’s curriculum, instructors, and participants likely contributed to the broadening of perspectives demonstrated.

Building international collaborations and professional networks is an essential component for addressing global health challenges (Barrett et al. 2011). The multi-institutional, multi-national representation of Rx One Health instructors and participants facilitates the development of a network of solution-oriented global health professionals, and with each cohort, the network grows. Future iterations of the Rx One Health program may benefit from an even greater representation of disciplines and home countries among participants. In particular, participants from low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), where the likelihood of emerging infectious disease threats are high and human and physical resources are most constrained (Jones et al. 2008; Vink et al. 2013), should be prioritized.

Operationalizing the OH approach requires that current and future health professionals train with a focus on cross-cutting issues, such as zoonotic diseases, public health, environmental degradation/climate change, economics, risk assessment and surveillance, and policy development (Vink et al. 2013). International working groups have identified OH competencies meant to guide educational development (Togami et al. 2018). Education through practical experience, addressing real-world problems, is the basis of OH capacity strengthening and the movement from theory to practice. In North America, there has been a significant shift in defining OH as core educational material in professional health programs. The North American Veterinary Medical Consortium identified OH knowledge as a core competency for veterinarians in 2011 (Amuguni et al. 2017). Similarly, the American Medical Association has endorsed the OH concept (Stroud et al. 2016). Most recently, the Council on Education for Public Health added OH to the accreditation criteria for US public health schools (Togami et al. 2018).

Future iterations of the Rx One Health Summer Institute should include the regular review of the curriculum to consider topics underrepresented in these formal OH educational offerings, such as social sciences, plant biology, antimicrobial resistance, and environmental law and policy (Togami et al. 2018). The timing and duration of the program should also be carefully considered to be inclusive of students concurrently enrolled in degree programs. It may be that these sorts of multi-disciplinary field programs would be best directed at final year professional or graduate students or graduates of health science programs, although securing time away from work may be problematic for some participants after completing degree programs and entering the workforce. To increase rigor of future program evaluations, results of multiple iterations could be combined to increase sample size and assessments could be collected from the same cohort longitudinally to help determine how training may translate to improved proficiency in the workplace.

Developing a workforce capable of anticipating and responding to global health challenges is a top priority. Professional trainings like Rx One Health are necessary to fill gaps identified in currently available health and medical programs. Long-term success and sustainability of these trainings must be addressed and include institutional and financial support. Many US agencies, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), United States Agency for International Development (USAID), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), and Department of Defense (DoD), as well as international organizations such as World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nation’s (UN) Environment Programme, stand to gain from a more integrated and collaborative OH workforce (Barrett et al. 2011).

Education is the basis for OH capacity development (Vink et al. 2013). Overall, the Rx One Health Summer Institute provides a model for increasing accessibility to OH education. Its emphasis on applied and practical training provides opportunities for participants to develop communication and problem-solving skills across disciplinary and cultural settings. These types of training programs can augment OH curricular offerings, generating a workforce that is capable of integrating OH competencies into public and global health practice at multiple levels and converting them into meaningful action.

Conclusions

Intensive short courses, such as the Rx One Health Summer Institute, provide an effective and implementable strategy by which to contribute to the development of a global workforce capable of collaborating with communities and other stakeholders to solve complex health challenges at the human–animal–plant–ecosystem interface. Training programs can be used as a forum for collaboration among health disciplines, allowing for the development of multi-national and multi-cultural cohorts of each year’s students and encouraging the ongoing development of a solution-oriented community of global health professionals, a necessary component for success of the OH approach.

References

Association of American Medical Colleges (2019) 2019 Medical School Graduation Questionnaire: All Schools Summary Report. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges

Amuguni HJ, Mazan M, Kibuuka R (2017) Producing interdisciplinary competent professionals: integrating One Health core competencies into the veterinary curriculum at the University of Rwanda. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education 44(4):649–659. https://doi.org/10.3138/jvme.0815-133r

Barrett MA, Bouley TA, Stoertz AH, Stoertz RW (2011) Integrating a One Health approach in education to address global health and sustainability challenges. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 9(4):239–245

Conrad PA, Mazet JA, Clifford D, Scott C, Wilkes M (2009) Evolution of a transdisciplinary “One Medicine-One Health” approach to global health education at the University of California, Davis. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 92(4):268–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2009.09.002

Davis MF, Rankin SC, Schurer JM, Cole S, Conti L, Rabinowitz P, COHERE Expert Review Group (2017) Checklist for One Health Epidemiological Reporting of Evidence (COHERE). One Health. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2017.07.001

Drain PK, Primack A, Hunt DD, Fawzi WW, Holmes KK, Gardner P (2007) Global health in medical education: a call for more training and opportunities. Academic Medicine 82(3):226–230. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e3180305cf9

Dye JF, Schatz IM, Rosenberg BA, Coleman ST (2000) Constant comparison method: a kaleidoscope of data. The Qualitative Report 4(1):1–10

Frankson R, Hueston W, Christian K, Olson D, Lee M, Valeri L, Hyatt R, Annelli J, Rubin C (2016) One health core competency domains. Frontiers in Public Health 4(192):1–6

Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N, Evans T, et al. (2010) Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 376:1923–1958. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61854-5

Gilardi KVK, Else JG, Beasley VR (2004) Envirovet summer institute: integrating veterinary medicine into ecosystem health practice. EcoHealth 1(1):S50–S55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-004-0113-7

Gostin LO, Friedman EA (2015) The sustainable development goals: One-Health in the world’s development agenda. Journal of the American Medical Association 314(24):2621–2622. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.16281

Jones KE, Patel NG, Levy MA, Storeygard A, Balk D, Gittleman JL, Daszak P (2008) Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 451:990–993. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06536

Mazet JAK, Clifford DL, Coppolillo PB, Deolalikar AB, Erickson JD, Kazwala RR (2009) A “one health” approach to address emerging zoonoses: the HALI project in Tanzania. PLOS Medicine 6(12):e1000190. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000190

Mazet JAK, Hamilton GE, Dierauf LA (2006) Educating veterinarians for careers in free-ranging wildlife medicine and ecosystem health. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education 33(3):352–360. https://doi.org/10.3138/jvme.33.3.352

Nyatanyi T, Wilkes M, McDermott H, Nzietchueng S, Gafarasi I, Mudakikwa A, et al. (2017) Implementing One Health as an integrated approach to health in Rwanda. BMJ Global Health 2:e000121. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000121

Raidl M, Johnson S, Gardiner, K., Denham, M., Spain, K., Lanting, R., et al. (2004) Use retrospective surveys to obtain complete data sets and measure impact in extension programs. Journal of Extension 42(2):1–8

Reid SA, McKenzie J, Woldeyohannes SM (2016) One Health research and training in Australia and New Zealand. Infection Ecology & Epidemiology 6:1–9. https://doi.org/10.3402/iee.v6.33799

Rwego IB, Babalobi OO, Musotsi P, Nzietchueng S, Tiambo CK, Kabasa JD, Naigaga I, Kalema-Zikusoka G, Pelican K (2016) One Health capacity building in sub-Saharan Africa. Infection Ecology & Epidemiology 6:1–9. https://doi.org/10.3402/iee.v6.34032

Schwind JS, Gilardi KVK, Beasley VR, Mazet JAK, Smith WA (2016) Advancing the “One Health’ workforce by integrating ecosystem health practice into veterinary medical education: The Envirovet Summer Institute. Health Education Journal 75(2):170–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896915570396

Sikkema R, Koopmans M (2016) One Health training and research activities in Western Europe. Infection Ecology & Epidemiology 6:1–9. https://doi.org/10.3402/iee.v6.33703

Stroud C, Kaplan B, Logan JE, Gray GC (2016) One Health training, research, and outreach in North America. Infection Ecology & Epidemiology 6:1–16.

Togami E, Gardy JL, Hansen GR, Poste GH, Rizzo DM, Wilson ME, Mazet JAK (2018) Core competencies in One Health education: what are we missing? NAM Perspectives. https://doi.org/10.31478/201806a

USAID PREDICT (2018) Publications and training guides. One Health Institute, University of California, Davis. https://www2.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/ohi/predict/predict_publications.cfm. Accessed December 13, 2018

Vink WD, McKenzie JS, Cogger N, Borman B, Muellner P (2013) Building on a foundation for ‘one health’: an education strategy for enhancing and sustaining national and regional capacity in endemic and emerging zoonotic disease management. In: One Health: The Human-Animal-Environment Interfaces in Emerging Infectious Diseases, Mackenzie JS, Jeggo M, Daszak P, Richt JA (editors), New York: Springer, pp 185–205

Wiggins G, McTighe J (2005) Understanding by Design, 2nd ed., Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development

Wu J, Liu L, Wang G, Lu J (2016) One Health in China. Infection Ecology & Epidemiology 6(1):33843. https://doi.org/10.3402/iee.v6.33843

Zinsstag J. (2012) Convergence of ecohealth and One Health. EcoHealth 9(4):371–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-013-0812-z

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge partners in Tanzania and Rwanda who made a truly experiential learning environment possible: Health for Animals and Livelihood Improvement (HALI) Project (Christoper Kilonzo, Goodluck Paul, Abel Ekiri, Zikankuba Sijali, Asha Makweta, Alphonce Msigwa, Mwokozi Mwanzalila), Veterinary Investigation Center—Tanzania (Simon Nong’ona), Tanzania Veterinary Laboratory Agency (Hilda Mrema), Sokoine University of Agriculture (Robinson Mdegela, Maulilio Kipanyula), Tanzania National Parks (Epaphras Alex), Ifakara Health Institute (Robert Sumaye, Solomon Mwakasungula, Catherine Mkindi, Grace Mwangoka, Said Jongo), University of Iringa (Geofrey Matata), Ruaha Carnivore Project, Wildlife Connection, APOPO, Strengthening Protected Area Network in Southern Tanzania (Godwell Meing’ataki), University of Rwanda (Phillip Cotton, Hilda Vasanthakaalam), Rwanda Development Board (Eugene Mutangana), Rwanda Agriculture Board (Isidore Gafarasi), Rwanda Biomedical Center (Jose Nyamusore), Rwanda Wildlife Conservation Association (Olivier Nsengimana), Gorilla Doctors (Julius Nziza, Jean Bosco Noheri, Michael Cranfield), University of California Got Safe Milk (Bethany Henrick, Sara Garcia, Blaise Iraguha, and Utah Division of Wildlife Resources (Annette Roug). We would also like to thank the University of California One Health Institute team who worked tirelessly to ensure the program ran smoothly from inception to evaluation: Lavonne Hull, Brooke Genovese, Lisa Milbrodt, Elizabeth Leasure, Katherine Leasure, Pamela Roualdes, David Wolking, and Brian Bird.

Funding

This program benefited from support from funding organizations and universities which supported participant training costs and travel. Instructor participation, logistics, and training materials were also supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development; the U.S. Department of Defense, Defense Threat Reduction Agency; the University of California, Davis’ Schools of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine; the Sokoine University of Agriculture; the University of California Global Health Institute; and the University of California, Davis Global Affairs Seed Grant Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Berrian, A.M., Wilkes, M., Gilardi, K. et al. Developing a Global One Health Workforce: The “Rx One Health Summer Institute” Approach. EcoHealth 17, 222–232 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-020-01481-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-020-01481-0