Highlights

-

Various MOF materials were synthesized and investigated as ZIB cathodes.

-

A long-term stable ZIF-8@Zn anode was proposed by coating ZIF-8 material on the surface of zinc foils.

-

High-performance aqueous ZIBs were constructed using the Mn(BTC) cathode and the ZIF-8@Zn anode.

Abstract

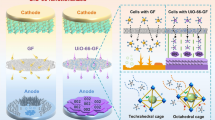

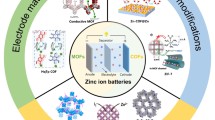

Rechargeable aqueous zinc-ion batteries (ZIBs) have been gaining increasing interest for large-scale energy storage applications due to their high safety, good rate capability, and low cost. However, the further development of ZIBs is impeded by two main challenges: Currently reported cathode materials usually suffer from rapid capacity fading or high toxicity, and meanwhile, unstable zinc stripping/plating on Zn anode seriously shortens the cycling life of ZIBs. In this paper, metal–organic framework (MOF) materials are proposed to simultaneously address these issues and realize high-performance ZIBs with Mn(BTC) MOF cathodes and ZIF-8-coated Zn (ZIF-8@Zn) anodes. Various MOF materials were synthesized, and Mn(BTC) MOF was found to exhibit the best Zn2+-storage ability with a capacity of 112 mAh g−1. Zn2+ storage mechanism of the Mn(BTC) was carefully studied. Besides, ZIF-8@Zn anodes were prepared by coating ZIF-8 MOF material on Zn foils. Unique porous structure of the ZIF-8 coating guided uniform Zn stripping/plating on the surface of Zn anodes. As a result, the ZIF-8@Zn anodes exhibited stable Zn stripping/plating behaviors, with 8 times longer cycle life than bare Zn foils. Based on the above, high-performance aqueous ZIBs were constructed using the Mn(BTC) cathodes and the ZIF-8@Zn anodes, which displayed an excellent long-cycling stability without obvious capacity fading after 900 charge/discharge cycles. This work provides a new opportunity for high-performance energy storage system.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries have been widely used in modern society [1]. However, security problems and increasing production cost pose challenges for their large-scale applications in the field of electric vehicles [2,3,4]. Researchers are committed to seeking alternative electrochemical energy storage systems to lithium-ion batteries. Many new-type rechargeable batteries using multivalent metal ions (e.g., Zn2+, Mg2+, and Al3+) as charge carriers have been proposed successively [5,6,7]. Among them, rechargeable aqueous zinc-ion batteries (ZIBs) have been considered as highly promising candidate for the next-generation energy storage system, because they are safe, low cost, and environmental benign [5]. In order to meet the demands of common energy consumption, two main issues should be addressed for the ZIBs. One is exploring suitable cathode materials for the reversible intercalation/extraction of zinc-ions [8, 9], and the other is exploring stable zinc metal anodes because this is essential for ZIBs to realize a long cycle life [10,11,12,13].

To find high-performance cathode materials for ZIBs, many attempts have been made [14]. Up to now, several types of ZIB cathode materials have been reported, including Mn-based materials [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22], V-based materials [23,24,25,26,27,28,29], Prussian blue analogs [30,31,32], and some other cathode materials such as Mo6S8 [33], quinone [34], and poly(benzoquinonyl sulfide) [35]. Mn-based materials, especially manganese oxides, possess the advantages such as low cost and environmental friendliness, but they suffer from the problems of rapid capacity fading and poor rate performance [36]. V-based cathode materials generally exhibit superior Zn2+-storage ability [37, 38], whereas serious toxicity limits their large-scale applications for ZIBs [10]. The Zn2+-storage capacity of Prussian blue analogs is only about 50 mAh g−1, which determines that the Prussian blue analogs may be not qualified to construct high-energy ZIBs [30]. In view of the above discussion, developing high-performance cathode materials for ZIBs is still a challenge. Furthermore, metallic Zn electrode owns an ultrahigh volumetric capacity and low redox potential (− 0.76 V vs. standard hydrogen electrode), which enable it to be a promising anode for ZIBs [5, 39, 40]. However, in practical applications, repeated deposition/dissolution of Zn inclines to form zinc dendrites/protuberances, leading to severe polarization and a short circuit of the batteries [41]. Some modification strategies such as introducing additives, employing gel electrolyte, using 3D current collectors, and creating the protection layer have been proposed to regulate Zn stripping/plating behaviors and realized dendrite-free zinc metal anodes [11, 12, 42, 43]. In a word, stabilizing zinc anodes is also critical to realize long-life ZIBs.

Exploring new potential materials such as metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) may open opportunities for addressing these problems. MOFs are characterized by highly porous structure, designable frameworks, and multifunctionality [44,45,46]. In the past two decades, MOFs have been widely used in energy storage systems such as lithium-ion batteries [47], supercapacitors [48], and fuel cells [49]. Recently, MOFs are attracting increasing interests in the field of ZIBs. For instance, a MnOx/N-doped carbon cathode material was synthesized based on a MOF template and provided a Zn2+-storage capacity of 305 mAh g−1 even after 600 charge/discharge cycles [36]. Besides, a MOF-based single-ion Zn2+ solid-state electrolyte with high ionic conductivity, high Zn2+ transference number, and good electrochemical stability was designed to achieve dendrite-free Zn batteries [50]. These researches imply that MOFs may provide new opportunities to construct high-performance ZIBs.

Herein, we synthesized five kinds of MOFs materials, including Mn(BTC), Mn(BDC), Fe(BDC), Co(BDC), and V(BDC) (in which BDC is 1,4-dicarboxybenzene and BTC is 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylic acid.) and investigated their electrochemical behaviors as ZIB cathodes. Among these MOFs materials, Mn(BTC) showed the best Zn2+ storage capability. Zn2+ storage mechanism of the Mn(BTC) cathode was then comprehensively studied. Besides, we developed a long-term stable ZIF-8@Zn anode by coating ZIF-8 material on the surface of zinc foils. Furthermore, high-performance aqueous ZIBs were constructed using the Mn(BTC) cathodes and the ZIF-8@Zn anodes, which exhibited an excellent cycling stability with 92% capacity retention after 900 charge/discharge cycles. This work opens up a new door for achieving high-performance aqueous zinc-ion batteries based on MOFs materials.

2 Experimental Section

2.1 Synthesis of MOF Materials

To synthesize Mn(BTC), 1225 mg Mn(CH3COO)2·4H2O and 300 mg polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP) were dissolved in ethanol/H2O (125/125 mL) to get solution A, and meanwhile, 2250 mg trimesic acid (H3BTC) was dissolved in another ethanol/H2O (125/125 mL) system to get solution B. Then, solution B was added slowly into solution A under continuous stirring. After 10 min, the reaction mixture was aged without interruption for 24 h. The products were collected after centrifugation, washing several times with ethanol and complete drying in an oven at 60 °C. Fe(BDC), Mn(BDC), Co(BDC), and V(BDC) were synthesized according to previously reported methods [51,52,53,54,55].

2.2 Preparation of ZIF-8@Zn Anode

ZIF-8 was purchased from J&K Scientific Ltd. The as-received ZIF-8 and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) were mixed with a mass ratio of 8:2 in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) solvent to form a homogeneous slurry. Then, the slurry was uniformly coated onto a Zn foil and dried at 80 °C overnight in a vacuum to obtain the ZIF-8-coated Zn (i.e., ZIF-8@Zn) anodes, in which the mass of the ZIF-8 coating was about 1.1 mg cm−2.

2.3 Material Characterization

Crystallographic and structure analysis was carried out by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku 2500, Cu Kα radiation, λ = 0.154056 nm) with a scan rate of 5° min−1 over 2-theta ranging from 5° to 70°. Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) was performed on a Zeiss Supra55 scanning electron microscope. Elemental analysis was characterized by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) on the FE-SEM. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, ESCALAB 250X, Thermo Fisher, United Kingdom) was used for characterizing the valence variation. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR, Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS 50) spectroscopy was used to identify functional groups in the MOF materials at pristine state and various charge/discharge states. Element content in electrolytes was analyzed by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES).

2.4 Electrochemical Measurements of MOF Cathodes

The electrochemical performance of various MOF cathodes was evaluated in CR2032 coin cells with zinc foil anode, air-laid paper separator, and 2 M ZnSO4 aqueous electrolyte. To prepare the MOF cathodes, the synthesized MOF powder was mixed with acetylene black and PVDF with a weight ratio of 7:2:1 in NMP solvent and then coated onto a stainless-steel current collector and dried at 80 °C overnight. The mass loading of MOF materials on current collectors is about 1.0 mg cm−2. For the assembled cells, cyclic voltammetry (CV) tests were carried out on a VMP3 multichannel electrochemical station (Bio-Logic Science Instruments SA) at a sweep rate of 0.5 mV s−1, and galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) tests were performed on a LAND CT2001 battery tester at current density of 50 mA g−1.

2.5 Electrochemical Measurements of ZIF-8@Zn Anodes

Electrochemical behaviors of the ZIF-8@Zn anodes were characterized through ZIF-8@Zn||ZIF-8@Zn symmetrical cells, in which both the negative and positive electrodes were a ZIF-8@Zn disk (with diameter of 12 mm), air-laid paper was used as the separator, and 2 M ZnSO4 (or 2 M ZnSO4 + 0.1 M MnSO4) aqueous solution was used as the electrolyte. For comparison, Zn||ZnSO4||Zn symmetrical cells were also assembled, in which pure Zn foils served as Zn electrodes. Electrochemical stability of these symmetric cells was evaluated by GCD tests at different current densities of 0.25–2 mA cm−2 and different charge/discharge capacities of 0.05–0.4 mAh cm−2 on a LAND CT2001 battery tester. The impedance measurements of symmetrical cells were taken on a VMP3 multichannel electrochemical station (Bio-Logic Science Instruments SA) between 300 kHz and 0.01 Hz.

2.6 Construction and Electrochemical tests of Mn(BTC) Cathode//ZIF-8@Zn Anode ZIBs

The MOF//ZIF-8@Zn ZIBs were constructed based on the Mn(BTC) cathode, ZIF-8@Zn anode, an air-laid paper separator, and 2 M ZnSO4 (or 2 M ZnSO4 + 0.1 M MnSO4) electrolyte. CV and GCD measurements were taken on the Bio-Logic VMP3 electrochemical station and the LAND CT2001 battery tester, respectively.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Material Characterization and Electrochemical Properties of MOF Cathodes

Structure and morphology of the as-synthesized MOF materials including Mn(BTC), Mn(BDC), Fe(BDC), Co(BDC), and V(BDC) were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron microscope (SEM). Figures 1a–e and S1 display that the Mn(BTC) and Fe(BDC) are composed of spherical and octahedral particles with size of 1–10 μm, respectively, and the other three MOF samples have irregular-shaped micromorphologies. As shown in Fig. 1f and Fig. S2, the XRD patterns of the synthesized MOF materials are consistent with previously reported literature [51,52,53,54,55], indicating that Mn(BTC), Mn(BDC), Fe(BDC), Co(BDC), and V(BDC) MOFs were successfully synthesized. The crystalline structures of these MOF materials are depicted in Fig. S3.

To evaluate Zn2+-storage ability of the above MOF materials as ZIB cathodes, cyclic voltammetry (CV) and galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) tests were conducted in 2 M ZnSO4 aqueous electrolyte. These MOF materials are selected as ZIB cathodes because the transition metal centers of Mn, Fe, Co, and V have proved to be active sites in electrochemical energy storage systems [56,57,58,59,60]. Meanwhile, BDC and BTC ligands are conventional ligands for MOF materials, and their lightweight feature is beneficial for the MOF materials to achieve a higher theoretical capacity considering that ligands usually cannot be redox sites for metal-ion storage [61]. Corresponding CV curves are shown in Fig. 2a–e. For the Mn(BTC) cathode, it can operate in a voltage window of 1.0–1.9 V (vs. Zn2+/Zn), and reversible redox peaks are observed on the CV curves (Fig. 2a), preliminarily demonstrating effective Zn2+ storage in the Mn(BTC). For the CV curves of the Mn(BDC) and Fe(BDC) MOF cathodes in Fig. 2b, c, there also emerge 1–3 pairs of reversible redox peaks, but the peak currents of the Fe(BDC) MOF are much smaller. The redox peaks in the CV curves of the Co(BDC) and V(BDC) are not obvious, and response currents are very small (Fig. 2d, e), suggesting a poor Zn2+-storage ability. Figure 2f displays charge/discharge curves at a current of 50 mA g−1 of the five MOF cathode materials. The Mn(BTC) exhibits several voltage plateaus in its discharge curve and delivers the highest Zn2+-storage capacity of 112 mAh g−1. Specific capacity of the Mn(BDC) cathode is about 48 mAh g−1. In contrast, the other three MOF cathodes including Fe(BDC), Co(BDC), and V(BDC) are incapable of effectively storing Zn2+, which is reflected by their very low capacities of less than 10 mAh g−1. Obviously, for the above MOF samples, only Mn(BTC) is promising to be utilized as a high-performance cathode material for ZIBs. Despite this, the Mn(BTC) shows a modest cycling stability during repeated Zn2+ storage-release processes (Fig. S4). This issue needs to be resolved based on the reveal of Zn2+-storage mechanism of the Mn(BTC) cathode.

3.2 Energy Storage Mechanism of the Mn(BTC) Cathode

Zn2+-storage mechanism of the Mn(BTC) cathode in ZnSO4 electrolyte is further investigated. Evolution of the phase composition and micromorphology of the Mn(BTC) electrode during Zn2+ storage-release processes were characterized by XRD and SEM, as shown in Fig. 3. When the fresh Mn(BTC) cathode is charged to 1.9 V at 50 mA g−1, “nanoflower-like” and “rod-like” particles appear (Fig. 3b). The “nanoflower” particles densely distribute on the surface of the electrode. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis in Fig. S5 points out that the “nanoflower” particles contain Mn and O elements, and the main composition elements of the “rod-like” particles are C, O, and Zn. When the Mn(BTC) cathode is then discharged to 1.0 V (Fig. 3c), the “rod-like” particles still exist, but the “nanoflower-like” particles disappear, and meanwhile, some large flakes form. The XRD results of the cathode at different charge–discharge states are shown in Fig. 3d. Compared with the original state, XRD pattern of the Mn(BTC) cathode at the fully charged state (i.e., 1.9 V) shows obvious differences. The main peaks (at 10.4°, 20.8°, 29.4°, 38.0°, and 42.4°) of the Mn(BTC) disappear, and some new peaks emerge (at 17.5°, 18.6°, 21.9°, 26.4°, 27.0°, and 35.5°), which means that there arises a phase transition reaction and new phases form undergoing charging. XRD pattern at the fully discharged state (i.e., 1.0 V) shows the characteristic diffraction peaks of ZnSO4·3Zn(OH)2·5H2O (denoted as BZSP). Therefore, the above-mentioned large flakes in Fig. 3c are considered as BZSP. Besides, from the fully charged state to the fully discharged state, some diffraction peaks (e.g., at 17.5°, 18.6°, 26.4°, 27.0°, and 35.5°) of the cathode remain unchanged positions. No PDF cards of MnO2 can match well with these diffraction peaks, and they still remain their positions at the fully discharged state, so these diffraction peaks do not belong to MnO2. These diffraction peaks are thought to originate from the “rod-like” particles that are observed in Fig. 3b, c.

To figure out what the “rod-like” and “nanoflower-like” compounds (Fig. 3b, c) are, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) were further carried out in Fig. 4. The high-resolution Mn 2p XPS spectrum of the Mn(BTC) cathode at fully charged state (Fig. 4a) shows that the Mn 2p3/2 and Mn 2p1/2 peaks situate at 642.1 and 653.8 eV, respectively, with the peak separation of 11.7 eV. These values are consistent with the reported parameters for MnO2 [62,63,64,65]. Considering that these “nanoflower-like” particles contain Mn element while “rod-like” particles do not (as discussed in Fig. S5a), the “nanoflower-like” particles are determined to be MnO2. In Fig. 4b, peak separation of Mn 3s orbit decreases from 6.4 eV for the original Mn(BTC) cathode to 4.7 eV for the fully charged Mn(BTC) cathode, indicating the increase in the Mn oxidation state after charging process [19]. The O 1s core-level spectrum in Fig. 4c can be divided into four main peaks. Especially, the peak centered at 529.7 eV is in accord with the typical bond of Mn–O–Mn [66].

FTIR spectra of the Mn(BTC) cathode at original, charging, and discharging states are presented in Fig. 4d. In the FTIR spectrum of the original Mn(BTC), the absorption peaks of O–H at 3082 cm−1 and C=O at 1720 cm−1 from 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylic acid disappear, while the asymmetric stretching vibrations of –COO– and symmetric stretching vibrations of –COO– are detected in the regions of 1612–1545 and 1433–1372 cm−1, respectively. This is an evidence that the manganese ions have been successfully coordinated with the 1,3,5-BTC ligands in the Mn(BTC) material [56]. When the Mn(BTC) is charged to 1.9 V, the asymmetric stretching vibration of –COO– at 1612 cm−1 shifts to a new band at 1628 cm−1. Meanwhile, the symmetric stretching vibration of –COO– at 1372 cm−1 shifts to a new band at 1383 cm−1. They are coordination characteristic bands of Zn(BTC) MOF materials [67]. These suggest that zinc-ion substitute manganese-ion to be coordinated with -COOH to form Zn(BTC). When the Mn(BTC) cathode is then discharged to 1.0 V, there is no distinct change for these typical bands, suggesting that Zn(BTC) remains stable during discharge process.

Based on the above analysis, we speculate possible reaction paths of the Mn(BTC) cathode during charge–discharge processes. During the first charge process, there occurs a transformation from Mn(BTC) to Zn(BTC), and Mn2+ dissolves into electrolyte. These Mn2+ is oxidized to MnO2 on the cathode surface through a normal manganese deposition reaction as the charging process proceeds. The reaction paths were further confirmed by plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES) tests. As shown in Table S1, Mn element concentration in electrolyte was detected when the cathode was charged/discharged to various states. Mn element concentration in electrolyte is 6.15 and 4.62 mg L−1 when the cathode is charged to 1.8 and 1.9 V, respectively. Decrease in Mn concentration in electrolyte is attributed to manganese deposition reaction. Subsequently, the deposited MnO2 serves as a host for Zn2+ and H+ storage in the following charge/discharge processes, which is the reason that we detected the formation of BZSP during charge/discharge processes (Fig. 3c, d) [68]. It worth noting that the BTC organic ligands of Mn(BTC) cathodes are not involved in the Zn-storage redox process, not only because the BTC ligands have been proved to be redox-innocent ligands [61] but also because they are always detected during charge/discharge processes of our ZIB systems (which means that BTC would not directly participate in Zn-storage reactions). However, BTC ligand is an indispensable part of Mn(BTC) because it constructs the three-dimensional framework of MOF materials. Interestingly, as shown in Fig. S6, Zn(BTC) particles seem to be the main by-product in this system and the formation of BZSP by-product is suppressed in this system compared with previously reported MnO2 cathode [68]. Unlike densely arranged BZSP flakes generated in MnO2//Zn ZIBs [68], these rod-like Zn(BTC) particles (generated in Mn(BTC)//Zn ZIBs) do not impede the direct contact between electrolyte and electrode materials, which is beneficial to ions diffusion and prolonged cycle life of the ZIBs.

In the above-proposed reaction pathways, the oxidation reaction from Mn(BTC) to MnO2 plays an important role in this system. On the one hand, MnO2 is capable of delivering a high capacity, but on the other hand, MnO2 generally suffers from rapid capacity fading due to the dissolution of manganese from the MnO2 electrode [15]. Therefore, the poor cycling stability of the Mn(BTC)//ZnSO4//Zn system as discussed in Fig. S4 is considered to be mainly caused by the dissolution of MnO2.

3.3 MOF Material Stabilized Zn Metal Anodes

To achieve stable zinc anodes, we introduced a ZIF-8 coating on bare Zn foil. Electrochemical stability of the ZIF-8-coated Zn foil electrode (i.e., ZIF-8@Zn) was characterized in symmetrical ZIF-8@Zn||ZIF-8@Zn coin cells at a current density of 0.25 mA cm−2 and a charge/discharge capacity of 0.05 mAh cm−2. Figure 5a shows the cycling performance of bare Zn foil electrode and the ZIF-8@Zn electrode based symmetric cells with 2 M ZnSO4 electrolyte. It can be seen that a sudden short circuit appears after ~ 20 h stripping/plating for bare Zn foil. By contrast, the ZIF-8@Zn electrode works stably for at least 170 h and corresponding polarization voltage almost keeps constant, implying that the ZIF-8@Zn electrode has superior cycle stability. Furthermore, compared with the first cycle charge/discharge profile of the bare Zn foil in Fig. 5b, the ZIF-8@Zn electrode demonstrates a lower polarization voltage (120 vs. 200 mV for the bare Zn foil-based symmetric cells), which indicates a low energy barrier for metal nucleation on the surface of the ZIF-8@Zn electrode [69]. Very similarly, in the electrolyte of 2 M ZnSO4 + 0.1 M MnSO4 mixture solution (Fig. 5c, d), the ZIF-8@Zn electrode-based symmetric cells exhibit small polarization voltages and a long-term stable charge/discharge behavior over 170 h, whereas the bare Zn foil electrode-based symmetric cells perform poorly. The remarkably improved cycling stability of the ZIF-8@Zn anode are also observed at larger current densities of 0.5–2 mA cm−2 and higher Zn deposited depth of 0.1–0.4 mAh cm−2 (Fig. S7). All batteries exhibit stable cycling life over 150 h, further confirming the benefits of the ZIF-8@Zn anode on Zn stripping/plating behaviors. Besides, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) test was also conducted to study the interfacial properties of bare Zn and ZIF-8@Zn anodes. As shown in Fig. S8, bare Zn electrodes delivered a large interfacial resistance and charge transfer resistance (estimated from the semicircle arc at high frequency range), which is due to passivation surface layers on Zn foils [70]. By contrast, the ZIF-8@Zn electrodes show a smaller interfacial resistance since the ZIF-8 coating provides a more stable electrode interface to guide a uniform Zn stripping/plating process.

Cycling performance of symmetrical cells with bare Zn foil and ZIF-8@Zn electrodes in a and b 2 M ZnSO4 and c and d 2 M ZnSO4 + 0.1 M MnSO4 electrolytes. Applied current density is 0.25 mA cm−2 with Zn deposition/dissolution capacity of 0.05 mAh cm−2. b, d The first-cycle voltage profiles of symmetrical cells with bare Zn foil and ZIF-8@Zn electrodes

Potential mechanism for the optimized electrochemical performance of the ZIF-8@Zn electrode is further investigated. We analyzed the morphology evolution of the bare Zn foil electrode and the ZIF-8@Zn electrode before and after 100 charge/discharge cycles by SEM and EDS mapping. As shown in Fig. 6a, b, many large protuberances appear on the surface of the Zn foil after cycling, suggesting uneven zinc plating/stripping process during repeated charge/discharge cycles. EDS mapping in Fig. 6c and Fig. S9 demonstrates that these protuberances contain O and Zn elements; thus, they are zinc oxides/hydroxides, as reported in the literature [11]. Cross-sectional SEM image (Fig. S10a, b) further shows some dead Zn particles on the surface of the bare Zn foil after cycling. In Fig. 6d, we can see that porous ZIF-8 coating is on the surface of the ZIF-8@Zn electrode, and after cycling (Fig. 6e, f), no large protuberances/dendrites appear. Besides, cross-sectional SEM and EDS images of the ZIF-8@Zn electrode (Fig. S10c, d) show that ZIF-8 layer does not fall off the Zn foil after 100 cycles, which means the ZIF-8 coating is stable in ZIBs. A schematic illustration for the morphology evolution of bare Zn and ZIF-8@Zn electrodes during repeated Zn stripping/plating is presented in Fig. 6g. According to the literature [71,72,73,74], Zn inclines to deposit on some sites to form small protuberances/dendrites during the plating process. These small protuberances/dendrites then generate inhomogeneous electric field, which is apt to attract Zn2+ to grow into uncontrolled protuberances/dendrites. When stripping, these large protuberances/dendrites incline to dissolve from their root positions, leading to the formation of “dead” Zn. Furthermore, the vigorously growing zinc protuberances/dendrites may easily pierce through the separator and cause a short circuit. For ZIF-8@Zn electrodes, the porous structure of ZIF-8 coating can homogenize the zinc-ion flux, avoiding an uneven distribution of the electric field and thus inhibiting the formation of protuberances/dendrites [75,76,77].

SEM images and EDS mapping of bare Zn electrode a before and b, c after 100 stripping/plating cycles, ZIF-8@Zn electrode d before, and e, f after 100 stripping/plating cycles. g Schematic illustration for morphology change of the bare Zn foil and ZIF-8@Zn electrodes during repeated Zn stripping/plating processes

3.4 ZIBs of Mn(BTC) Cathode//ZIF-8@Zn Anode

An aqueous zinc-ion battery using the above-studied Mn(BTC) cathode and ZIF-8@Zn anode was constructed, as illustrated in Fig. 7a. 2 M ZnSO4 aqueous solution was chosen as the electrolyte. CV curves at a scan rate of 0.5 mV s−1 are displayed in Fig. 7b. It can be seen that there emerge two reduction peaks at 1.22 and 1.37 V and one oxidation peak at 1.83 V in the initial cycle, and the oxidation peak is corresponding to the oxidation reaction from Mn(BTC) to MnO2 as discussed above. From the second cycles, two pairs of reversible redox peaks appear, indicating a reversible Zn2+ storage/release process. The rate performance is displayed in Fig. 7c. The battery delivers a discharge capacity of 112, 63, 40, and 14 mAh g−1, respectively, at current densities of 50, 100, 200, and 500 mA g−1. Figure 7d shows cycling performance of the battery. It can be observed that the Mn(BTC) exhibits a discharge capacity of about 55 mAh g−1 at a current density of 100 mA g−1 after activation process. However, the capacity rapidly fades to only 27 mAh g−1 after 50 charge/discharge cycles, indicating a poor cycling stability. As investigated above, such a poor cycling performance can be mainly ascribed to the dissolution of MnO2 from Mn(BTC) cathode. Therefore, to optimize cycling performance of the Mn(BTC) cathode and the assembled battery, MnSO4 was added to the ZnSO4 electrolyte, because Mn2+ in the electrolyte is able to suppress manganese dissolution [78, 79]. In 2 M ZnSO4 + 0.1 M MnSO4 electrolyte, their electrochemical performance is significantly improved. As shown in Fig. 7e, peak currents of CV curves with the addition of Mn2+ in the electrolyte are much higher than that without Mn2+ (Fig. 7b), which indicates a better Zn2+-storage ability. A superior rate capability is also achieved in Fig. 7f, with the capacity of 170, 142, 80, and 46 mAh g−1 at current densities of 50, 100, 500, and 1000 mA g−1, respectively. The high rate performance could be ascribed to the stabilization and excellent kinetics of the cathode under the case of Mn2+ addition in ZnSO4 electrolyte [15]. Cycling performance test (Fig. 7g) shows that the battery delivers a reversible capacity of 150 mAh g−1 after 50 cycles at 0.1 A g−1. Furthermore, the battery exhibits 92% capacity retention after 900 cycles at 1000 mA g−1 in Fig. 7h, which indicates excellent long-cycling stability. It is worth noting that the cycle performance of Mn(BTC) cathode in ZnSO4 + MnSO4 electrolyte is superior to many previously reported manganese oxide cathodes shown in Table S2 at similar current densities, but the capacity and rate capability are not as good as widely studied MnO2 materials. Despite this, MOF cathode materials are still promising for Zn2+ storage because further research may find some Mn-MOF or other MOF materials with much better Zn2+-storage ability, considering that MOF materials possess diverse structure, controllable chemical composition, very high specific surface area, and many other merits. CV curves (Fig. S11a) at various scan rates were also recorded and used to analyze Zn2+ storage kinetics of the cathode. When the scan rate increases from 0.5 to 5 mV s−1, both anodic and cathodic peaks slightly shift, which is due to increased polarization at higher scan rates [80]. According to the previous literature, the relationship between peak current (i) and the scan rate (v) can be represented by Eqs. 1 and 2 [81]:

where a and b are adjustable parameters. In general, b value ranges from 0.5 to 1.0. The coefficient b of 0.5 indicates a faradic reaction, and the coefficient b of 1.0 means a complete surface-controlled capacitive process [82]. The b values calculated by slope of the log(v)-log(i) plots (Fig. S11b) for redox peaks (Fig. S11a) are 0.54 and 0.67. This indicates that Zn2+ storage in the Mn(BTC) cathode is mainly through faradic reactions.

a Schematic of the Mn(BTC) cathode//ZIF-8@Zn anode ZIBs. Electrochemical performance of the ZIBs: b CV curves at 0.5 mV s−1, c rate capability, and d cycling performance at 100 mA g−1 in 2 M ZnSO4 electrolyte; e CV curves at 0.5 mV s−1, f rate capability and cycling performance at g at 100 mA g−1, and h at 1000 mA g−1 in 2 M ZnSO4 + 0.1 M MnSO4 electrolyte

4 Conclusions

In summary, a high-performance aqueous zinc-ion battery system was realized based on MOF materials. Several kinds of MOF materials were synthesized first and investigated as cathode materials for ZIBs. During them, Mn(BTC) MOF showed a high capacity and its Zn2+ storage mechanism was revealed such as a transformation reaction from Mn(BTC) to MnO2 during charge process. In addition, a porous ZIF-8 coating was utilized to protect Zn foil anodes, which led to a uniform electrolyte flux and significantly inhibited the formation of zinc protuberances/dendrites. An aqueous zinc-ion battery was constructed based on the Mn(BTC) cathode and the ZIF-8 stabilized Zn anode. Benefiting from the synergetic effect of Mn(BTC) cathode and Mn2+ additive in the electrolyte, high capacity and excellent long-term cycling ability were simultaneously realized. This work proves that by exploring MOF materials, high-performance aqueous zinc-ion batteries can be achieved.

References

T.-H. Kim, J.-S. Park, S.K. Chang, S. Choi, J.H. Ryu, H.-K. Song, The current move of lithium ion batteries towards the next phase. Adv. Energy Mater. 2(7), 860–872 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201200028

J.-M. Tarascon, M. Armand, Issues and challenges facing rechargeable lithium batteries. Nature 414(6861), 359–367 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/35104644

B. Scrosati, J. Hassoun, Y.-K. Sun, Lithium-ion batteries. A look into the future. Energy Environ. Sci. 4(9), ee01388b (2011). https://doi.org/10.1039/c1ee01388b

M.A. Hannan, M.M. Hoque, A. Mohamed, A. Ayob, Review of energy storage systems for electric vehicle applications: issues and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 69, 771–789 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.11.171

C. Xu, B. Li, H. Du, F. Kang, Energetic zinc ion chemistry: the rechargeable zinc ion battery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51(4), 933–935 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201106307

H.D. Yoo, I. Shterenberg, Y. Gofer, G. Gershinsky, N. Pour, D. Aurbach, Mg rechargeable batteries: an on-going challenge. Energy Environ. Sci. 6(8), 2265–2279 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1039/c3ee40871j

N. Jayaprakash, S.K. Das, L.A. Archer, The rechargeable aluminum-ion battery. Chem. Commun. 47(47), 12610–12612 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1039/c1cc15779e

A. Konarov, N. Voronina, J.H. Jo, Z. Bakenov, Y.-K. Sun, S.-T. Myung, Present and future perspective on electrode materials for rechargeable zinc-ion batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 3(10), 2620–2640 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.8b01552

M. Song, H. Tan, D. Chao, H.J. Fan, Recent advances in Zn-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28(41), 1802564 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201802564

L. Dong, W. Yang, W. Yang, Y. Li, W. Wu, G. Wang, Multivalent metal ion hybrid capacitors: a review with a focus on zinc-ion hybrid capacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 7(23), 13810–13832 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/c9ta02678a

Z. Kang, C. Wu, L. Dong, W. Liu, J. Mou et al., 3D porous copper skeleton supported zinc anode toward high capacity and long cycle life zinc ion batteries. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7(3), 3364–3371 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b05568

K.E. Sun, T.K. Hoang, T.N. Doan, Y. Yu, X. Zhu, Y. Tian, P. Chen, Suppression of dendrite formation and corrosion on zinc anode of secondary aqueous batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9(11), 9681–9687 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.6b16560

F. Wang, O. Borodin, T. Gao, X. Fan, W. Sun et al., Highly reversible zinc metal anode for aqueous batteries. Nat. Mater. 17(6), 543–549 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-018-0063-z

W. Xu, Y. Wang, Recent progress on zinc-ion rechargeable batteries. Nano-Micro Lett. 11(1), 90 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-019-0322-9

H. Pan, Y. Shao, P. Yan, Y. Cheng, K.S. Han et al., Reversible aqueous zinc/manganese oxide energy storage from conversion reactions. Nat. Energy 1(5), 16039 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nenergy.2016.39

N. Zhang, F. Cheng, J. Liu, L. Wang, X. Long et al., Rechargeable aqueous zinc-manganese dioxide batteries with high energy and power densities. Nat. Commun. 8(1), 405 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00467-x

B. Jiang, C. Xu, C. Wu, L. Dong, J. Li, F. Kang, Manganese sesquioxide as cathode material for multivalent zinc ion battery with high capacity and long cycle life. Electrochim. Acta 229, 422–428 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2017.01.163

W. Liu, J. Hao, C. Xu, J. Mou, L. Dong et al., Investigation of zinc ion storage of transition metal oxides, sulfides, and borides in zinc ion battery systems. Chem. Commun. 53(51), 6872–6874 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/c7cc01064h

J. Hao, J. Mou, J. Zhang, L. Dong, W. Liu, C. Xu, F. Kang, Electrochemically induced spinel-layered phase transition of Mn3O4 in high performance neutral aqueous rechargeable zinc battery. Electrochim. Acta 259, 170–178 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2017.10.166

C. Zhong, B. Liu, J. Ding, X. Liu, Y. Zhong et al., Decoupling electrolytes towards stable and high-energy rechargeable aqueous zinc-manganese dioxide batteries. Nat. Energy (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-020-0584-y

X. Guo, J. Zhou, C. Bai, X. Li, G. Fang, S. Liang, Zn/MnO2 battery chemistry with dissolution-deposition mechanism. Mater. Today Energy 16, 100396 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtener.2020.100396

C. Zhu, G. Fang, S. Liang, Z. Chen, Z. Wang et al., Electrochemically induced cationic defect in MnO intercalation cathode for aqueous zinc-ion battery. Energy Storage Mater. 24, 394–401 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2019.07.030

P. Hu, T. Zhu, J. Ma, C. Cai, G. Hu et al., Porous V2O5 microspheres: a high-capacity cathode material for aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Chem. Commun. 55(58), 8486–8489 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/c9cc04053f

F. Wan, L. Zhang, X. Dai, X. Wang, Z. Niu, J. Chen, Aqueous rechargeable zinc/sodium vanadate batteries with enhanced performance from simultaneous insertion of dual carriers. Nat. Commun. 9(1), 1656 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04060-8

Y. Cai, F. Liu, Z. Luo, G. Fang, J. Zhou, A. Pan, S. Liang, Pilotaxitic Na1.1V3O7.9 nanoribbons/graphene as high-performance sodium ion battery and aqueous zinc ion battery cathode. Energy Storage Mater. 13, 168–174 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2018.01.009

D. Chao, C.R. Zhu, M. Song, P. Liang, X. Zhang et al., A high-rate and stable quasi-solid-state zinc-ion battery with novel 2D layered zinc orthovanadate array. Adv. Mater. 30(32), 1803181 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201803181

P. He, G. Zhang, X. Liao, M. Yan, X. Xu et al., Sodium ion stabilized vanadium oxide nanowire cathode for high-performance zinc-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 8(10), 1702463 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201702463

W. Li, K. Wang, S. Cheng, K. Jiang, A long-life aqueous Zn-ion battery based on Na3V2(PO4)2F3 cathode. Energy Storage Mater. 15, 14–21 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2018.03.003

Q. Su, X. Cao, T. Yu, X. Kong, Y. Wang et al., Binding MoSe2 with dual protection carbon for high-performance sodium storage. J. Mater. Chem. A 7(40), 22871–22878 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/C9TA06870H

L. Zhang, L. Chen, X. Zhou, Z. Liu, Towards high-voltage aqueous metal-ion batteries beyond 1.5 V: the zinc/zinc hexacyanoferrate system. Adv. Energy Mater. 5(2), 1400930 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201400930

R. Trocoli, F. La Mantia, An aqueous zinc-ion battery based on copper hexacyanoferrate. ChemSusChem 8(3), 481–485 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.201403143

Z. Liu, G. Pulletikurthi, F. Endres, A prussian blue/zinc secondary battery with a bio-ionic liquid-water mixture as electrolyte. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8(19), 12158–12164 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.6b01592

M.S. Chae, J.W. Heo, S.C. Lim, S.T. Hong, Electrochemical zinc-ion intercalation properties and crystal structures of ZnMo6S8 and Zn2Mo6S8 chevrel phases in aqueous electrolytes. Inorg. Chem. 55(7), 3294–3301 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b02362

L. Li, Q. Zhao, Z. Luo, Y. Lu, H. Ma et al., High-capacity aqueous zinc batteries using sustainable quinone electrodes. Sci. Adv. 4(3), eaa01761 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aao1761

G. Dawut, Y. Lu, L. Miao, J. Chen, High-performance rechargeable aqueous Zn-ion batteries with a poly(benzoquinonyl sulfide) cathode. Inorg. Chem. Front. 5(6), 1391–1396 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1039/c8qi00197a

Y. Fu, Q. Wei, G. Zhang, X. Wang, J. Zhang et al., High-performance reversible aqueous Zn-ion battery based on porous MnOx nanorods coated by MOF-derived N-doped carbon. Adv. Energy Mater. 8(26), 1801445 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201801445

D. Kundu, B.D. Adams, V. Duffort, S.H. Vajargah, L.F. Nazar, A high-capacity and long-life aqueous rechargeable zinc battery using a metal oxide intercalation cathode. Nat. Energy 1(10), 16119 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nenergy.2016.119

M.H. Alfaruqi, V. Mathew, J. Song, S. Kim, S. Islam et al., Electrochemical zinc intercalation in lithium vanadium oxide: a high-capacity zinc-ion battery cathode. Chem. Mater. 29(4), 1684–1694 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b05092

L. Dong, X. Ma, Y. Li, L. Zhao, W. Liu et al., Extremely safe, high-rate and ultralong-life zinc-ion hybrid supercapacitors. Energy Storage Mater. 13, 96–102 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2018.01.003

X. Xie, S. Liang, J. Gao, S. Guo, J. Guo et al., Manipulating the ion-transfer kinetics and interface stability for high-performance zinc metal anodes. Energy Environ. Sci. 13(2), 503–510 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1039/c9ee03545a

S. Higashi, S.W. Lee, J.S. Lee, K. Takechi, Y. Cui, Avoiding short circuits from zinc metal dendrites in anode by backside-plating configuration. Nat. Commun. 7, 11801 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11801

Y. Tang, C. Liu, H. Zhu, X. Xie, J. Gao et al., Ion-confinement effect enabled by gel electrolyte for highly reversible dendrite-free zinc metal anode. Energy Storage Mater. 27, 109–116 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2020.01.023

C. Li, X. Xie, S. Liang, J. Zhou, Issues and future perspective on zinc metal anode for rechargeable aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Mater. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/eem2.12067

H. Furukawa, K.E. Cordova, M. O’Keeffe, O.M. Yaghi, The chemistry and applications of metal-organic frameworks. Science 341(6149), 1230444 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1230444

B.Y. Guan, X.Y. Yu, H.B. Wu, X.W.D. Lou, Complex nanostructures from materials based on metal-organic frameworks for electrochemical energy storage and conversion. Adv. Mater. 29(47), 1703614 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201703614

H. Wang, Q.-L. Zhu, R. Zou, Q. Xu, Metal-organic frameworks for energy applications. Chem 2(1), 52–80 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chempr.2016.12.002

J.W. Choi, D. Aurbach, Promise and reality of post-lithium-ion batteries with high energy densities. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1(4), 16013 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/natrevmats.2016.13

P. Simon, Y. Gogotsi, Materials for electrochemical capacitors. Nat. Mater. 7(11), 845–854 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat2297

E.D. Wachsman, K.T. Lee, Lowering the temperature of solid oxide fuel cells. Science 334(6058), 935–939 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1204090

Z. Wang, J. Hu, L. Han, Z. Wang, H. Wang et al., A MOF-based single-ion Zn2+ solid electrolyte leading to dendrite-free rechargeable Zn batteries. Nano Energy 56, 92–99 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2018.11.038

Z. Cui, Q. Liu, C. Xu, R. Zou, J. Zhang et al., A new strategy to effectively alleviate volume expansion and enhance the conductivity of hierarchical MnO@C nanocomposites for lithium ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 5(41), 21699–21708 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/c7ta05986h

H. Hu, X. Lou, C. Li, X. Hu, T. Li et al., A thermally activated manganese 1,4-benzenedicarboxylate metal organic framework with high anodic capability for Li-ion batteries. New J. Chem. 40(11), 9746–9752 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1039/c6nj02179d

K.M.L. Taylor-Pashow, J.D. Rocca, Z. Xie, S. Tran, W. Lin, Postsynthetic modifications of iron-carboxylate nanoscale metal-organic frameworks for imaging and drug delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131(40), 14261–14263 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1021/ja906198y

X. Hu, H. Hu, C. Li, T. Li, X. Lou, Q. Chen, B. Hu, Cobalt-based metal organic framework with superior lithium anodic performance. J. Solid State Chem. 242, 71–76 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2016.07.021

T. Kim, H. Kim, T.-S. You, J. Kim, Carbon-coated V2O5 nanoparticles derived from metal-organic frameworks as a cathode material for rechargeable lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 727, 522–530 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.08.179

S. Maiti, A. Pramanik, U. Manju, S. Mahanty, Reversible lithium storage in manganese 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylate metal-organic framework with high capacity and rate performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 7(30), 16357–16363 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.5b03414

D. Wu, Z. Guo, X. Yin, Q. Pang, B. Tu et al., Metal-organic frameworks as cathode materials for Li-O2 batteries. Adv. Mater. 26(20), 3258–3262 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201305492

T. Yamada, K. Shiraishi, H. Kitagawa, N. Kimizuka, Applicability of MIL-101 (Fe) as a cathode of lithium ion batteries. Chem. Commun. 53(58), 8215–8218 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/c7cc01712j

W. Yan, Z. Guo, H. Xu, Y. Lou, J. Chen, Q. Li, Downsizing metal-organic frameworks with distinct morphologies as cathode materials for high-capacity Li-O2 batteries. Mater. Chem. Front. 1(7), 1324–1330 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/c6qm00338a

B. He, Q. Zhang, P. Man, Z. Zhou, C. Li et al., Self-sacrificed synthesis of conductive vanadium-based metal-organic framework nanowire-bundle arrays as binder-free cathodes for high-rate and high-energy-density wearable Zn-ion batteries. Nano Energy 64, 103935 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2019.103935

Z. Zhang, H. Yoshikawa, K. Awaga, Monitoring the solid-state electrochemistry of Cu(2,7-aqdc) (aqdc = anthraquinone dicarboxylate) in a lithium battery: coexistence of metal and ligand redox activities in a metal-organic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136(46), 16112–16115 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1021/ja508197w

Z.-P. Feng, G.-R. Li, J.-H. Zhong, Z.-L. Wang, Y.-N. Ou, Y.-X. Tong, MnO2 multilayer nanosheet clusters evolved from monolayer nanosheets and their predominant electrochemical properties. Electrochem. Commun. 11(3), 706–710 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elecom.2009.01.001

H. Zhu, Q. Liu, J. Liu, R. Li, H. Zhang, S. Hu, Z. Li, Construction of porous hierarchical manganese dioxide on exfoliated titanium dioxide nanosheets as a novel electrode for supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta 178, 758–766 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2015.08.073

B. Thirupathi, P.G. Smirniotis, Nickel-doped Mn/TiO2 as an efficient catalyst for the low-temperature SCR of NO with NH3: catalytic evaluation and characterizations. J. Catal. 288, 74–83 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2012.01.003

A.L. Reddy, M.M. Shaijumon, S.R. Gowda, P.M. Ajayan, Coaxial MnO2/carbon nanotube array electrodes for high-performance lithium batteries. Nano Lett. 9(3), 1002 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1021/nl803081j

W. Chen, G. Li, A. Pei, Y. Li, L. Liao et al., A manganese-hydrogen battery with potential for grid-scale energy storage. Nat. Energy 3(5), 428–435 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-018-0147-7

L. Xu, E.-Y. Choi, Y.-U. Kwon, Ionothermal synthesis of a 3D Zn-BTC metal-organic framework with distorted tetranuclear [Zn4(μ4-O)] subunits. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 11(10), 1190–1193 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2008.07.001

Y. Huang, J. Mou, W. Liu, X. Wang, L. Dong, F. Kang, C. Xu, Novel insights into energy storage mechanism of aqueous rechargeable Zn/MnO2 batteries with participation of Mn2+. Nano-Micro Lett. 11(1), 49 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-019-0278-9

R. Zhang, X.R. Chen, X. Chen, X.B. Cheng, X.Q. Zhang, C. Yan, Q. Zhang, Lithiophilic sites in doped graphene guide uniform lithium nucleation for dendrite-free lithium metal anodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56(27), 7764–7768 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201702099

L. Fan, H.L. Zhuang, W. Zhang, Y. Fu, Z. Liao, Y. Lu, Stable lithium electrodeposition at ultra-high current densities enabled by 3D PMF/Li composite anode. Adv. Energy Mater. 8(15), 1703360 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201703360

X.B. Cheng, R. Zhang, C.Z. Zhao, Q. Zhang, Toward safe lithium metal anode in rechargeable batteries: a review. Chem. Rev. 117(15), 10403–10473 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00115

J.W. Gallaway, D. Desai, A. Gaikwad, C. Corredor, S. Banerjee, D. Steingart, A lateral microfluidic cell for imaging electrodeposited zinc near the shorting condition. J. Electrochem. Soc. 157(12), 1279–1286 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1149/1.3491355

K.N. Wood, E. Kazyak, A.F. Chadwick, K.H. Chen, J.G. Zhang, K. Thornton, N.P. Dasgupta, Dendrites and pits: untangling the complex behavior of lithium metal anodes through operando video microscopy. ACS Cent. Sci. 2(11), 790–801 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1021/acscentsci.6b00260

J.F. Parker, C.N. Chervin, E.S. Nelson, D.R. Rolison, J.W. Long, Wiring zinc in three dimensions re-writes battery performance-dendrite-free cycling. Energy Environ. Sci. 7(3), 1117–1124 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1039/c3ee43754j

L. Kang, M. Cui, F. Jiang, Y. Gao, H. Luo et al., Nanoporous CaCO3 coatings enabled uniform Zn stripping/plating for long-life zinc rechargeable aqueous batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 8(25), 1801090 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201801090

Z. Zhao, J. Zhao, Z. Hu, J. Li, J. Li et al., Long-life and deeply rechargeable aqueous Zn anodes enabled by a multifunctional brightener-inspired interphase. Energy Environ. Sci. 12(6), 1938–1949 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/c9ee00596j

M. Cui, Y. Xiao, L. Kang, W. Du, Y. Gao et al., Quasi-isolated Au particles as heterogeneous seeds to guide uniform Zn deposition for aqueous zinc-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2(9), 6490–6496 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaem.9b01063

M. Chamoun, W.R. Brant, C.-W. Tai, G. Karlsson, D. Noréus, Rechargeability of aqueous sulfate Zn/MnO2 batteries enhanced by accessible Mn2+ ions. Energy Storage Mater. 15, 351–360 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2018.06.019

X. Wu, Y. Xiang, Q. Peng, X. Wu, Y. Li et al., A green-low-cost rechargeable aqueous zinc-ion battery using hollow porous spinel ZnMn2O4 as the cathode material. J. Mater. Chem. A 5(34), 17990–17997 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/c7ta00100b

B. Tang, G. Fang, J. Zhou, L. Wang, Y. Lei et al., Potassium vanadates with stable structure and fast ion diffusion channel as cathode for rechargeable aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Nano Energy 51, 579–587 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2018.07.014

V. Augustyn, J. Come, M.A. Lowe, J.W. Kim, P.L. Taberna et al., High-rate electrochemical energy storage through Li+ intercalation pseudocapacitance. Nat. Mater. 12(6), 518–522 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat3601

G. Fang, Z. Wu, J. Zhou, C. Zhu, X. Cao et al., Observation of pseudocapacitive effect and fast ion diffusion in bimetallic sulfides as an advanced sodium-ion battery anode. Adv. Energy Mater. 8(19), 1703155 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201703155

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the financial supports from International Science & Technology Cooperation Program of China (No. 2016YFE0102200), Shenzhen Technical Plan Project (No. JCYJ20160301154114273), National Key Basic Research (973) Program of China (No. 2014CB932400), and Local Innovative and Research Teams Project of Guangdong Pearl River Talents Program (2017BT01N111).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pu, X., Jiang, B., Wang, X. et al. High-Performance Aqueous Zinc-Ion Batteries Realized by MOF Materials. Nano-Micro Lett. 12, 152 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-00487-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-00487-1