Abstract

Background

Exposure to airborne fine particulate matter (PM2.5) has been declared to be harmful to human kidney. However, whether activation of the autophagic pathway plays key roles in the nephrotoxicity caused by PM2.5 exposure is still poorly understood. The aim of this study was to explore the mechanism of kidney damage after PM2.5 exposure in vivo and in vitro.

Results

In the present study, statistically significant alterations in water intake, urine flow rate and mean blood pressure were observed between the concentrated PM2.5 (PM2.5) group and the filtered air (FA) group. Exposed animals showed severe edema of renal tubular epithelial cells, capillary congestion, reduction of the glomerular urinary space and early pro-fibrotic state. Moreover, significant increases in the levels of early kidney damage markers were observed in the exposed rats and these animals exhibited more apoptosis rate in kidney cells. In addition, PM2.5 exposure activated the autophagic pathway, as evidenced by LC3-I to LC3-II conversion, activation of P62 and beclin-1. All of these effects are in concurrence with the presence of more autophagosomes both in vivo and in vitro after PM2.5 exposure.

Conclusions

Taken together, our findings indicated that PM2.5 induced renal function impairment via the activation of the autophagic pathway in renal tubular epithelial cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A report on the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2016 estimated that nearly 3 million people die every year due to air pollution-related diseases [43]. PM2.5 refers to the complex mixture small particles and liquid droplets with aerodynamic diameter ≤ 2.5 μm in the atmosphere, and is an important indicator for assessing air pollution [43, 55]. PM2.5 mainly deposits in lung tissues after inhaling the respiratory tract, and can even diffuse in the blood circulation system through the alveolar-capillary barrier, affecting distal organs such as liver and kidneys [25, 36]. Zhang et al. [51] found that severe histopathological changes in hepatocyte edema and glomerular atrophy occurred in rats induced by intratracheal instillation of PM2.5. Recently, some epidemiological studies have reported a strong and consistent association between PM2.5 exposure and renal function decline [5, 30]. Bowe et al. [2] estimated that the global burden of incident chronic kidney disease (CKD) attributable to PM2.5 was about 6.95 million in 2016, and air pollution may be an important risk factor for the prevalence of kidney disease. Experimental studies have also shown that mid-/long-term exposure to high levels of PM2.5 can induce kidney damage in rodent models [1, 16].

Although the respiratory system is the primary target organ for toxicity of PM2.5, epidemiological evidence has indicated that PM2.5 exposure is an important risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [3]. The strong correlation between chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease has been demonstrated by both observational studies and a meta-analysis [33]. Renal insufficiency and patients undergoing dialysis are prone to cardiovascular diseases have been reported in clinical practice, which indicates a potential interaction between the kidney and the cardiovascular system [1]. Tavera Busso et al. observed more severe alterations of fibrosis, mesangial expansion, tubular epithelial cells detachment, decrease glomerular and tubular lumen volumes in a spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR) model after sub-chronic exposure to PM2.5 than healthy animals [43]. Moreover, histological analysis performed by Yan et al. [49] showed PM2.5 advanced glomerulosclerosis and a punctual tubular damage of the kidney in a diabetic rat model after subchronic exposure to PM2.5. Endothelial dysfunction is viewed as one of the common pathophysiological mechanisms in cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease [40]. Aztatzi-Aguilar et al. [1] revealed that early kidney damage was induced by subchronic exposure to PM2.5 in rats due to angiotensin/bradykinin systems’ imbalance and a statistically significant increment in median blood pressure. At present, studies have confirmed that autophagy of cardiovascular endothelium was the potential mechanism of PM2.5-induced cardiovascular dysfunction [12, 45, 56]. In contrast, the contribution of PM2.5 exposure to endothelial damage in kidneys via the autophagic pathway has not been fully clarified at the cellular and molecular levels.

Autophagy is a physiological process whereby eukaryotic cells undergo self-digestion, which allows the degradation and recycling of unnecessary intracellular proteins and dysfunctional organelles via the autophagosome and lysosomes [9, 10, 41]. The formation of the autophagosome involves the action of multiple autophagy-related genes (Atgs), such as beclin-1 (Atg6), and microtubule-associated proteins light chain 3 (LC3) [9, 52]. Sequestosome1/P62 (SQSTM1) is a regulatory autophagy protein originally identified as a binding protein for nonreceptor-type tyrosine kinase P56Lck [19, 56]. Moreover, P62 has been found play key roles in the selective autophagy signaling pathway because of the interaction with both Keap1 and LC3. Autophagy is considered to be an adaptive response to stress, and plays an important role in maintaining cellular homeostasis during pathogenic conditions and diseases, as well as regulating caspase-independent apoptotic cell death [10, 56].

The kidney is an organ with rich and diverse endothelial cells [44]. Ding et al. [11] found that gold nanoparticles could induce autophagy of hypoxic human proximal tubule epithelial (HK-2) cells. The basal autophagy in the kidney is vital for the normal homeostasis of proximal tubules, but abnormal autophagy can impair renal function and increased p62 levels and oxidative stress [23, 28]. Therefore, we hypothesized that PM2.5 exposure induced autophagy of renal endothelial cells leading to the deterioration of the renal function. This work was designed to study the effect of PM2.5 exposure on kidney function of Sprague Dawley (SD) rats using a physiological inhalation exposure system. HK-2 cell line was also employed as an in vitro model to further investigate the potential mechanism triggered by PM2.5 exposure to renal dysfunction. Moreover, kidney injury molecule type-1 (KIM-1), a specific biomarker of damage to tubular cells, was detected to assess renal injury after PM2.5 exposure. Our findings would provide important insight into the involvement of PM2.5 pollution in kidney damage.

Materials and methods

Animal maintenance

A total of 20 SD male rats of 4-week-old were purchased from Jiexijie experimental animal co., LTD. (Shanghai, China). All animals were raised in the specific pathogen-free (SPF) environmental conditions at a temperature of 22–24 °C with 50–60% relative humidity and a 12-h day/night cycle. Rats had been allowed to drink and eat freely until when they were kept in metabolic cages. After 1-week acclimation, rats were randomly divided in two groups (10 per group): one group was exposed to filtered air and the other group was exposed to concentrated PM2.5. The study was subject to approval by the institutional animal care and use committees of Tongji University.

PM2.5 exposure system

A physiologically inhaled PM2.5 exposure system (Shanghai-MRTAS, patent #201510453600.8) was provided by the meteorological service of Shanghai. Concentrated particulate matter of the exposure system was generated using a versatile aerosol concentration enrichment system (VACES) as previously described [26, 47]. The PM2.5 exposure system which basically keeps the chemical properties of PM2.5 before concentration was located at the school of public health, Fudan University (130 Dongʼan Road, Shanghai, China), where ambient PM2.5 particles come mainly from traffic exhaust. The exposure experiments were performed for 8 h per day, 5 consecutive days per week from October 2018 to January 2019. The two PM2.5 monitors (PDR-1500, Thermo Scientific) were connected to the air inlets of the exposure and control chambers, respectively, and the real-time concentrations of PM2.5 in the atmosphere were determined by spectrophotometry [13].

Metabolic cage

After 5-day exposure, rats were placed in metabolic cages (Yuyan instrument, China) for 24 h each week. During the 24-h period, foods were not given to avoid contamination of the urine. The urine was harvested and water intake was estimated, then the urinary flow was calculated. These data were adjusted for body weight.

Measurement of blood pressure

MedLab biological signal acquisition and processing system (Nanjing Calvin Biotechnology, China) was used to record blood pressure. Animals were first fixed in the sleeve and warmed to a suitable temperature prior to each measurement to ensure adequate diastolic blood pressure. Then, more than three blood pressure measurements using a cutoff ring and a transducer placed on the proximal vein of the tail were performed. Basal measurement was evaluated 1 day before the initiation of the 12-week exposure and on the 7th day after every weekly exposure, with a metabolic cage period of 1 day for the animals to rest and hydrate. The mean blood pressure (MBP) was calculated as follows [1]:

Histology

Renal tissues were fixed with formaldehyde for more than 24 h, and then were dehydrated with alcohol, clarified by xylene, and embedded in paraffin. Slides were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain, as well as Masson’s Trichrome stain (Sigma Aldrich, USA). Images of three slides per animal were analyzed, were captured and determined by an optical microscope (Olympus, Japan); the median was obtained for each animal.

Transmission electron microscopy

Treated cells and kidney tissues were immediately fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C, then washed 3 times with 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and underwent in osmic acid for 2 h after post-fixation at room temperature [18]. Subsequently, cells were washed 3 times with 0.1 M PBS, then dehydrated in a graded alcohol series and embedded in epoxy resin. Then, ultrathin serial sections (60–100 nm) of embedded samples were cut using ultra-microtomy (Leica, EM UC7, Germany), stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined under an electron microscope (Tecnai G2 20 TWIN, FEI Company, USA) at 200 kv.

Apoptosis assay

The TdT-mediated dUTP nick labeling (TUNEL) technique was used for the determination of cell apoptosis in kidney tissues. Slides of kidney were deparaffinized, and a TUNEL assay kit was used to detect apoptosis according to the manufacture’s instructions (Roche, Shanghai, China). Images were observed and captured using a fluorescent microscope (Nikon, Japan).

Cells and culture

HK-2 cells provided by Professor Andong Qiu, School of Life Sciences and Technology, Tongji University, Shanghai, China, were cultured in DMEM/F12 (Biological Industries, Israel) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) and 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin (Solarbio, China). Exponentially growing cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2, with daily replacement of the cell culture medium. Cells were washed with PBS, digested with 0.25% trypsin (Solarbio, China) and seeded in new culture flasks/dishes after they reached 80% confluence.

Real-time quantitative PCR analysis

Total RNA of the kidney cortex was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNA was used as a template to examine the mRNA expression levels of target genes using SYBR® Green mixture (Takara, Dalian, China) on an ABI QuantStudio 7 detection system (Applied Biosystems, USA). GAPDH was taken as an internal control and the gene expressions were assessed using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The PCR cycle was as follows: initial denaturant at 95 °C for 6 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturing at 95 °C for 10 s, and annealing at 60 °C for 34 s. The primer sequences for real-time PCR were shown as following: (5′ → 3′): Rat-GAPDH forward GCCTTCCGTGTTCCTACC reverse CCTGCTTCACCACCTTCTT; Rat-KIM-1 forward GAGGTGGAGACTCTGGTTGA reverse TGGAGATTCCTGGATGGT; Rat-TGF-β forward CTAATGGTGGACCGCAACAAC reverse CACTGCTTCCCGAATGTCTGA; Rat-Smad2 forward ACCACTCTCTCCCCTGTCAATCA reverse AACCTAAGCAGAACCTCTCCGA.

Western blot analysis

Total protein of kidney tissues and cells was lysed in ice-cold NP40 buffer (Beyotime, China) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Then, the liquid supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 12000g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the protein concentrations were calculated using a BCA protein quantification kit (Beyotime, China). The protein samples were subjected to 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate polypropylene gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, MA, USA). The PVDF membranes were then blocked in 5% non-fat milk at room temperature for 1 h, incubated with specific primary antibodies KIM-1 (Cell Signaling Technology, USA), LC3, beclin-1, P62, GAPDH, and β-actin (Proteintech, USA) at 4 °C overnight, and subsequently incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Proteintech, USA) at room temperature for 1 h. After washing with TBST, the protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Image Quant LAS, 4000 mini). Protein expression was quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.4.2b, USA) and standardized to the expression of a housekeeping gene and is given in the fold change compared to that in the control samples.

Data analysis

Data was expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistical 19.0 software (IBM, USA). Independent-sample t test was used to compare the difference between PM2.5 and FA groups. Statistical analysis between multi-groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed Duncan’s multiple-comparison tests. p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

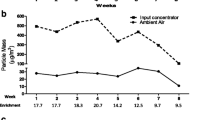

Exposure description and hydration state

During exposure periods, the mean concentration of PM2.5 outdoor (Xujiahui District, Shanghai) was 41.48 μg/m3 (19.2–83.8 μg/m3), and the average concentration in the exposed chamber was 255.71 μg/m3 (72.15–596.84 μg/m3) and 8.24 μg/m3 (4.52–13.54 μg/m3) in the control chamber, respectively. The average concentration of particulate enrichment was 6.16 times (2.91–13.69 times). These results showed that the concentration of PM2.5 in the exposed chamber was affected by PM2.5 concentration in outdoor air, which was consistent with the dynamic change of outdoor concentration (Fig. 1a). During the 12 weeks of exposure, the animalsʼ body weight was recorded every weekend. The results showed that there was no statistical difference between the FA and PM2.5 groups (Fig. 1b). In addition, water intake and urinary flow rates were measured during the 24-h period. During the exposure period, the water consumption of animals in the PM2.5 group was higher than that in the FA group, and there was a significant difference in the 8th, 10th and 11th weeks (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1c). Meanwhile, the results showed (Fig. 1d) that the urinary flow rate in the PM2.5 group was higher than that in the FA group, along with significant difference in all weeks except the 1st, 2nd and 12th weeks (p < 0.05).

PM2.5 concentration monitoring and the effects of PM2.5 on the physiological metabolism in rats. a During the exposure period, the mean PM2.5 concentrations of ambient air, exposure chamber and control chamber were monitored simultaneously, 5 days per week and 8 h per day. b Changes in rats’ body weight during exposure period. c The water consumption during 24-h period in the metabolic cages. d Urinary flow rates during 24 h in the metabolic cages. Values are significantly compared to FA group: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, independent-sample t test

Changes of mean blood pressure

In this study, MBP was used as a physiological parameter of vascular tone, which can be an indicator of perfusion pressure of organs. We assessed the basic blood pressure of the animals in each group and measured the tail blood pressure of the animals after weekly exposure. The results indicated that in the 5th, 7th, 8th, 10th and 12th week after exposure, the MBP of SD rats in the PM2.5 group was significantly higher than that in the FA group (all p < 0.05), while no significant differences were observed in other weeks (all p > 0.05) (Table 1). Several studies have linked PM2.5 with increases in the blood pressure, and elevated blood pressure serves as an indicator of cardiovascular stress and disruption of normative vascular homeostasis [6, 8, 27]. These results indicated that PM2.5 exposure affected vascular tone of experimental animals and probably the perfusion of organs.

Histology and pro-fibrotic state

After exposure to PM2.5 for 12 weeks, pathological changes of H&E-stained renal tissue samples showed the severe edema of renal tubular epithelial cells, capillary congestion and reduction of the glomerular urinary space, whereas the normal structures of glomerulus and tubular can be observed in the FA group (Fig. 2a). In addition, to further evaluate renal injury, we used Western blotting and RT-PCR to examine the protein and gene mRNA expression of KIM-1, a marker of early renal injury. Shown as Fig. 2c, d, mRNA expression of KIM-1 in renal cortex of PM2.5 group was significantly higher than those of FA group (p < 0.01), and levels of KIM-1 protein in serum of PM2.5 group were significantly higher than those of FA group (p < 0.01).

Renal histopathologic changes caused by PM2.5 exposure. a H&E stain of renal tissue (glomerulus marked by black arrow and renal tubules marked by the red arrow). b RT-PCR analysis of KIM-1 in kidney cortex, on histogram graphic** indicates statistical difference (p < 0.01), independent-sample t test. c, d WB analysis of KIM-1 in serum, on histogram graphic** indicates statistical difference (p < 0.01), independent-sample t test

Masson’s Trichromic stain was further used to estimate the changes of collagen deposition in renal tissue induced by PM2.5 exposure. As showing in Fig. 3a, compared with the control group, significant collagen deposition was observed in the kidney tissues of the PM2.5 group. mRNA expression levels of TGF-β and Smad2 were analyzed as inducers of early pro-fibrosis (Fig. 3b). We observed that mRNA expression levels of TGF-β and Smad2 in renal cortex of PM2.5 group were significantly higher than those of FA group (p < 0.05).

PM2.5 induced renal cell apoptosis of rats

The TUNEL method was used to further determine whether PM2.5 exposure could induce cell apoptosis in renal tissues. These results showed that green fluorescence points in renal tissues in the PM2.5 group were significantly more than those in the FA group (Fig. 4a). Compared with FA group, the proportion of apoptosis cells in PM2.5 group showed significantly statistical difference (p < 0.01) (Fig. 4b).

TUNEL analysis of rats’ kidney tissues. a Representative images are showing cell apoptosis in renal tissues induced by PM2.5. b Statistical analysis of the proportion of apoptosis cells. Cells with green light presented TUNEL-positive cells, on histogram graphic** indicates statistical difference (p < 0.01), independent-sample t test

PM2.5 induced increase of autophagy and changes of autophagic protein expression in renal tissues

As can be observed in Fig. 5, there were multiple layers (myeloid) of exposed animal renal tissue cells. To further clarify whether PM2.5 activated autophagy signaling-related molecules in renal cells, Western blotting was used to analyze the expression levels of LC3, P62, and beclin-1 proteins. Our results showed that compared with the FA group, protein signals of LC3 and P62 in PM2.5 group were significantly down-regulated, while protein signals of beclin-1 were significantly up-regulated (Fig. 6). The ratio of LC3II/LC3I and beclin-1 protein abundance in the PM2.5 group were significantly higher than that in the FA group, and the protein abundance of P62 was significantly lower than that in the FA group. Collectively, PM2.5 exposure triggered the intracellular autophagy signaling pathway in renal tissue.

Activation of autophagic pathway after PM2.5 exposure in rats. Western blots and quantitative expressions of LC3, beclin-1 and P62. GAPDH was used as the loading control, on histogram graphic* and on histogram graphic** indicate statistical difference (p < 0.05) and (p < 0.01), respectively, independent-sample t test

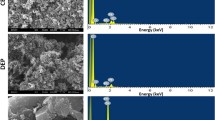

Morphological changes following PM2.5 treatment in HK-2 cells

We further examined the morphology of HK-2 cells following treatment with PM2.5 using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Untreated control HK-2 cells presented typical cellular morphology, including normal-sized nucleus, even distribution of microvilli on the cell surface. In contrast, HK-2 cells that were treated with PM2.5 (400 μg/mL) displayed an absence of microvilli on the surface of the cell membrane, along with an obvious swelling of the nucleus, and destruction of the cell membrane lysis. Moreover, high-magnification images showed the presence of numerous autophagic vacuoles, early autophagic vacuoles, and degradation autophagic vacuoles (Fig. 7).

PM2.5 induced the activation of autophagic pathways in HK-2 cells

To determine whether PM2.5 treatment also induced the activation of autophagic pathways in HK-2 cells, we examined the expression of LC3, which contains two species including activated LC3-I and processed IL3-II, as well as P62 and beclin1 using Western blot analyses. PM2.5 treatment resulted in a significant increase in the ratio of LC3-II to LC3-I content in a dose- and time-dependent manner, indicating that PM2.5 exposure induced the conversion of LC3-I to processed LC3-II (Fig. 8). Moreover, PM2.5 treatment significantly up-regulated protein expression levels of P62 and beclin1 compared to untreated control cells. Collectively, these findings demonstrated that PM2.5 induced the activation of the cascade of LC3, P62 and beclin1 proteins involved in the autophagic pathway in HK-2 cells.

Discussion

In the present study, the artificial climatic environment exposure system (Shanghai-METAS) was used to study the effects of PM2.5 exposure on kidney damage. This equipment which could maximally simulate “real world” PM2.5 exposure is the first comprehensive animal exposure system established in China, and has been effectively used to assess the effects of PM2.5 exposure on health and diseases development in rodent in several studies [13, 47, 48]. Interestingly, the results of this study also confirmed that subchronic exposure to PM2.5 led to kidney damage in SD rats.

The kidneys are complex organs, and they are vital in maintaining normal body functions such as urinary production, excretion/reabsorption, acid–alkaline homeostasis and endocrine function [22]. To investigate whether kidney adequate filtration was affected by PM2.5 exposure, the water consumption and urine volume of the animals within 24 h once a week were recorded during the exposure period. As shown in Fig. 1c, d, the alterations of water intake and urinary flow rate were observed between PM2.5 and FA groups after exposure to PM2.5, and the results were consistent with the previous report [1]. The stimulating effects of PM2.5 hygroscopic properties and nervous system, as well as adequate water needed in lung tissues to clean up the harm of PM2.5 particle deposition for self-protection, might be the main reasons for the increases of water consumption in rodent after PM2.5 exposure [1]. Moreover, it has been shown that administration of Cisplatin (CP) or CP + Cerium oxide nanoparticles (CeO2 NPs) in rats increased the water intake and urine volume compared with saline, indicated that the damaged renal tubules could cause the deterioration of capacity of tubular cells to reabsorb water, and subsequent polyuria leading to dehydration [34]. Similarly, the increase of urine volume was one of the nephrotoxicity characteristics in an acute renal failure (ARF) rat model induced by gentamicin in a study about plant extracts for the prevention and attenuation of ARF [14]. These results suggested that the physiological functions of the kidney were damaged, resulting in an imbalance of hydration state after exposure to PM2.5. However, the body weight of rats in both groups has not been affected during the exposure to PM2.5 period in this study (Fig. 1b).

PM2.5 exposure increased the risk of cardiovascular disease [17]. Vascular endothelial cells are the primary vascular barrier to local damage factors induced by exposure to PM2.5, such as inflammatory factors and free radicals, as well as toxic and harmful substances of PM2.5 [15]. Vascular endothelium plays key roles in regulating blood pressure, atherosclerosis and thrombosis, and PM2.5 exposure can lead to structural and functional impairment of vascular endothelial cells [37]. For this reason, we monitored MBP during animal exposure as an indicator of vascular response to PM2.5 to assess the effects of PM2.5 on peripheral blood pressure and organ blood perfusion. Our results showed that there was no difference in the basal blood pressure between the two groups. But in the 5th, 7th, 8th, 10th and 12th weeks, the MBP of the PM2.5 group was significantly higher than that of the FA group after subchronic exposure to PM2.5. Because of the close relationship between the physiological function of the kidney and systemic blood pressure, an increase in MBP could cause the renal peritubular capillaries damage.

Currently, a few studies have described that exposure to PM2.5 could cause pathological alterations of kidney tissues [1, 16, 43]. Here, both in vivo and in vitro experiments clarified that the morphological structures of renal tissues and HK-2 cells were damaged after PM2.5 exposure. H&E staining results of tissue sections indicated tubular and glomerular damage evidenced by the severe edema of renal tubular epithelial cells, capillary congestion and reduction of the glomerular urinary space (Fig. 2a). Moreover, PM2.5 treatment resulted in significant changes in cellular morphology in HK-2 cells, including destruction of the cell membrane lysis and swelling of the nucleus (Fig. 7). Similar histopathologic changes have been reported in diabetic nephropathy and acute kidney injury [4, 49]. KIM-1 is a transmembrane glycoprotein whose extracellular segments can be shed, and the levels in urine are often detected in clinical or experimental studies to diagnose acute kidney injury or early kidney damage [24, 42, 51]. In this study, the significant increases of KIM-1 protein expression in serum and KIM-1 mRNA expression in kidney tissues were observed after PM2.5 exposure in vivo experiment (Fig. 2b–d). Thus, these results indicated that exposure to PM2.5 induced damage to the proximal tubule epithelium.

Our results also showed that during the 12-week period of exposure to PM2.5, kidney tissue not only experienced sustained damage, but the body also activated a response to repair the damage. At the end of exposure, mRNA expression of TGF-β in renal tissues of the PM2.5 group was increased. TGF-β plays an important role in participating in post-injury repair of tissues by promoting the deposition of extracellular matrix components such as collagen [20]. But prolonged, uncontrolled TGF-β activation can lead to an overdose of extracellular matrix, leading to tissue fibrosis [38]. An increase of collagen deposition in renal tissue was observed by Masson’s Trichromic stain in this study. We speculated that long-term exposure to PM2.5 could lead to renal damage, but the body could induce collagen deposition through activation of TGF-β components to promote damage repair. However, the increased mRNA expression of Smad2 gene in renal tissues suggested that long-term exposure to PM2.5 may promote pro-fibrosis and renal dysfunction. Similarly, TGF-β1 and Smad2 played an important role in the process of renal fibrosis which has been confirmed in previous studies [31, 32].

To investigate the renal damage of SD rats exposed to PM2.5 at the cellular level, we first used transmission electron microscopy to observe the changes in renal cell microstructure. The results showed that there were lysosome vacuoles and multilayer (myeloid) substances in the cytoplasm of the kidney tissues of the exposed group. Moreover, TUNEL analysis was used to further analyze the degree of cell damage in kidney tissues and the results indicated that apoptosis responses were observed significantly in PM2.5 exposed rats. Previous studies suggested that apoptosis in renal tubular cells was considered as a causal factor in the development of kidney diseases/injury [39, 53]. Many in vivo and in vitro experiments have confirmed that PM2.5-induced inappropriate apoptosis (too much) is one of the potential mechanisms of PM2.5 health hazards [29, 46, 50, 54]. Therefore, we speculated that PM2.5 may enter the kidney through blood circulation, and then accumulate in cells, resulting in kidney damage.

As previously known, obvious autophagosomes and lysosome vacuoles were found in the cytoplasm of HK-2 cells after exposure by transmission electron microscopy. Autophagy refers to the catabolic process of self-digestion of abnormal substances in the cytoplasm of cells by lysosomes [7]. Beclin-1 plays a key role in early autophagosome formation, followed by LC3 which is a significant feature of autophagy level. P62 is an intracellular multifunctional protein acting on selective autophagy, which is mainly induced by stress and involved in a variety of signal transduction, including in the formation process of autophagosomes, as a bridge between LC3 and polyubiquitin protein; it can regulate the transport of damaged mitochondria into autophagosomes and degradation, and has an important regulatory role in the Nrf2/Keap1 signaling pathway [19, 21]. Studies have found that autophagy induced by PM2.5 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and human lung epithelial cells (A549) is characterized by significant increase in LC3-II and beclin-1 expression levels and LC3-II/LC3-I ratio [10, 12]. Our results showed that after exposure to PM2.5, LC3-I to LC3-II conversion, P62, and beclin-1 were activated. The accumulation of P62 indicates that intracellular autophagic flux is compromised, Keap1 is sequestered by P62 and can no longer bind Nrf2, leading to activated Nrf2 signaling which functions to protect cells against oxidative stress, environmental toxicants, and harmful chemicals through the induction of cytoprotective genes [21]. These data in vitro suggested that autophagic pathway played key roles for the activation of the cell self-protection mechanism in the HK-2 cells’ damage induced by PM2.5 exposure. In vivo assay, the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio and beclin-1 protein expression level in the PM2.5 group were significantly higher than those in the FA group, while the P62 protein expression level in the PM2.5 group was significantly lower than that in the FA group. These results revealed that PM2.5 exposure led to the occurrence of autophagy and autophagic flux in renal tissues, and P62 was a selective regulatory protein, and autophagy played an important role in PM2.5-induced HK-2 cytotoxicity and renal injury. The previous study confirmed that oxidized proteins-triggered autophagosome formation could prevent further oxidative stress to protect other cells [35]. The increased levels of ROS in HK-2 cells induced by PM2.5 exposure have been observed in our previous study [18]. Moreover, the expressions of Nrf2 and NQO1 proteins in the kidneys of the exposed animals were significantly lower than those of the FA group after PM2.5 exposure (data not displayed). Therefore, we considered that autophagy may be an adaptation process to prompt self-repair of kidney damage, and avoid ending up in a kidney failure process in the current study.

Conclusion

In summary, the present study demonstrated that PM2.5 exposure could promote autophagy in kidneys, especially renal tubular epithelial cells both in vitro and vivo. We further provided evidence that autophagy pathway was crucial for the progression of kidney damage induced by PM2.5 exposure, which was most likely via the activation of LC3, beclin-1 and P62 expressions. Our findings provided insight about the effects and mechanism of PM2.5 on renal injury.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets obtained and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SD:

-

Sprague–Dawley

- FA:

-

Filtered air

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PM2.5 :

-

Fine particulate matter

- HK-2:

-

Human proximal tubule epithelial cells

- KIM-1:

-

Kidney injury molecule-1

- TUNEL:

-

TdT-mediated dUTP nick labeling

- MBP:

-

Mean blood pressure

- Atgs:

-

Autophagy-related genes

- LC3:

-

Microtubule-associated proteins light chain 3

- P62:

-

Sequestosome1

- qPCR:

-

Quantitative Real-time PCR

References

Aztatzi-Aguilar OG, Uribe-Ramirez M, Narvaez-Morales J, De Vizcaya-Ruiz A, Barbier O (2016) Early kidney damage induced by subchronic exposure to PM2.5 in rats. Part Fibre Toxicol 13:68

Bowe B, Xie Y, Li T, Yan Y, Xian H, Al-Aly Z (2019) Estimates of the 2016 global burden of kidney disease attributable to ambient fine particulate matter air pollution. BMJ Open 9:e022450

Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA, Brook JR, Bhatnagar A, Diez-Roux AV, Holguin F, Hong Y, Luepker RV, Mittleman MA, Peters A, Siscovick D, Smith SC, Whitsel L, Kaufman JD (2010) Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 121:2331–2378

Chen L, Marko L, Kassmann M, Zhu Y, Wu K, Gollasch M (2014) Role of TRPV1 channels in ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury. PLoS ONE 9:e109842

Chen SY, Chu DC, Lee JH, Yang YR, Chan CC (2018) Traffic-related air pollution associated with chronic kidney disease among elderly residents in Taipei City. Environ Pollut 234:838–845

Chung M, Wang DD, Rizzo AM, Gachette D, Delnord M, Parambi R, Kang CM, Brugge D (2015) Association of PNC, BC, and PM2.5 measured at a central monitoring site with blood pressure in a predominantly near highway population. Int J Environ Res Public Health 12:2765–2780

Condello M, Pellegrini E, Caraglia M, Meschini S (2019) Targeting autophagy to overcome human diseases. Int J Mol Sci 20:725

Curto A, Wellenius GA, Mila C, Sanchez M, Ranzani O, Marshall JD, Kulkarni B, Bhogadi S, Kinra S, Tonne C (2019) Ambient particulate air pollution and blood pressure in peri-urban India. Epidemiology 30:492–500

Deng X, Zhang F, Rui W, Long F, Wang L, Feng Z, Chen D, Ding W (2013) PM2.5-induced oxidative stress triggers autophagy in human lung epithelial A549 cells. Toxicol In Vitro 27:1762–1770

Deng X, Zhang F, Wang L, Rui W, Long F, Zhao Y, Chen D, Ding W (2014) Airborne fine particulate matter induces multiple cell death pathways in human lung epithelial cells. Apoptosis 19:1099–1112

Ding F, Li Y, Liu J, Liu L, Yu W, Wang Z, Ni H, Liu B, Chen P (2014) Overendocytosis of gold nanoparticles increases autophagy and apoptosis in hypoxic human renal proximal tubular cells. Int J Nanomed 9:4317

Ding R, Zhang C, Zhu X, Cheng H, Zhu F, Xu Y, Liu Y, Wen L, Cao J (2017) ROS-AKT-mTOR axis mediates autophagy of human umbilical vein endothelial cells induced by cooking oil fumes-derived fine particulate matters in vitro. Free Radic Biol Med 113:452–460

Du X, Jiang S, Zeng X, Zhang J, Pan K, Zhou J, Xie Y, Kan H, Song W, Sun Q, Zhao J (2018) Air pollution is associated with the development of atherosclerosis via the cooperation of CD36 and NLRP3 inflammasome in ApoE(−/−) mice. Toxicol Lett 290:123–132

Ehsani V, Amirteimoury M, Taghipour Z, Shamsizadeh A, Bazmandegan G, Rahnama A, Khajehasani F, Fatemi I (2017) Protective effect of hydroalcoholic extract of Pistacia vera against gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Ren Fail 39:519–525

Feng S, Gao D, Liao F, Zhou F, Wang X (2016) The health effects of ambient PM2.5 and potential mechanisms. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 128:67–74

Ge C, Xu M, Qin Y, Gu T, Lv J, Wang M, Wang S, Ma Y, Lou D, Li Q, Hu L, Tan J (2018) iRhom2 loss alleviates renal injury in long-term PM2.5-exposed mice by suppression of inflammation and oxidative stress. Redox Biol 19:147–157

Huang W, Wang L, Li J, Liu M, Xu H, Liu S, Chen J, Zhang Y, Morishita M, Bard RL, Harkema JR, Rajagopalan S, Brook RD (2018) Short-term blood pressure responses to ambient fine particulate matter exposures at the extremes of global air pollution concentrations. Am J Hypertens 31:590–599

Huang X, Shi X, Zhou J, Li S, Zhang L, Zhao H, Kuang X, Li J (2020) The activation of antioxidant and apoptosis pathways involved in damage of human proximal tubule epithelial cells by PM2.5 exposure. Environ Sci Eur 32:2

Ichimura Y, Waguri S, Sou Y-S, Kageyama S, Hasegawa J, Ishimura R, Saito T, Yang Y, Kouno T, Fukutomi T, Hoshii T, Hirao A, Takagi K, Mizushima T, Motohashi H, Lee M-S, Yoshimori T, Tanaka K, Yamamoto M, Komatsu M (2013) Phosphorylation of p62 activates the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway during selective autophagy. Mol Cell 51:618–631

Ismaeel A, Kim J-S, Kirk JS, Smith RS, Bohannon WT, Koutakis P (2019) Role of transforming growth factor-β in skeletal muscle fibrosis: a review. Int J Mol Sci 20:2446

Jiang T, Harder B, Rojo de la Vega M, Wong PK, Chapman E, Zhang DD (2015) p62 links autophagy and Nrf2 signaling. Free Radic Biol Med 88:199–204

Johnston JG, Pollock DM (2018) Circadian regulation of renal function. Free Radic Biol Med 119:93–107

Kaushal GP, Shah SV (2016) Autophagy in acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 89:779–791

Khreba NA, Abdelsalam M, Wahab AM, Sanad M, Elhelaly R, Adel M, El-Kannishy G (2019) Kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM-1) as an Early predictor for acute kidney injury in post-cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) in open heart surgery patients. Int J Nephrol 2019:6265307

Li D, Li Y, Li G, Zhang Y, Jiang Li J, Chen H (2019) Fluorescent reconstitution on deposition of PM2.5 in lung and extrapulmonary organs. PNAS 116:2488–2493

Li Y, Zhou J, Rui X, Zhou L, Mo X (2019) PM2.5 exposure exacerbates allergic rhinitis in mice by increasing DNA methylation in the IFN-gamma gene promoter in CD4+ T cells via the ERK-DNMT pathway. Toxicol Lett 301:98–107

Liang R, Zhang B, Zhao X, Ruan Y, Lian H, Fan Z (2014) Effect of exposure to PM2.5 on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens 32:2130–2140 (discussion 2141)

Lin TA, Wu VC, Wang CY (2019) Autophagy in chronic kidney diseases. Cell 8:61

Liu J, Zhang J, Ren L, Wei J, Zhu Y, Duan J, Jing L, Sun Z, Zhou X (2019) Fine particulate matters induce apoptosis via the ATM/P53/CDK2 and mitochondria apoptosis pathway triggered by oxidative stress in rat and GC-2spd cell. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 180:280–287

Mehta AJ, Zanobetti A, Bind MA, Kloog I, Koutrakis P, Sparrow D, Vokonas PS, Schwartz JD (2016) Long-term exposure to ambient fine particulate matter and renal function in older men: the veterans administration normative aging study. Environ Health Perspect 124:1353–1360

Meng X-M, Tang PM-K, Li J, Lan HY (2015) TGF-Î2/Smad signaling in renal fibrosis. Front Physiol 6:82

Meng X, Huang X, Chung A, Qin W, Shao X, Igarashi P, Ju W, Bottinger E, Lan H (2010) Smad2 protects against TGF-beta_Smad3-mediated renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 21:1477–1487

Moody WE, Edwards NC, Madhani M, Chue CD, Steeds RP, Ferro CJ, Townend JN (2012) Endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular disease in early-stage chronic kidney disease: cause or association? Atherosclerosis 223:86–94

Nemmar A, Al-Salam S, Al Ansari Z, Alkharas ZA, Al Ahbabi RM, Beegam S, Yuvaraju P, Yasin J, Ali BH (2019) Impact of pulmonary exposure to cerium oxide nanoparticles on experimental acute kidney injury. Cell Physiol Biochem 52:439–454

Peixoto MS, de Oliveira Galvao MF, Batistuzzo de Medeiros SR (2017) Cell death pathways of particulate matter toxicity. Chemosphere 188:32–48

Pinkerton KE, Green FHY, Saiki C, Vallyathan V, Plopper CG, Gopal V, Hung D, Bahne EB, Lin SS, Ménache MG, Schenker MB (2000) Distribution of particulate matter and tissue remodeling in the human lung. Environ Health Perspect 108:1063–1069

Pope CA 3rd, Bhatnagar A, McCracken JP, Abplanalp W, Conklin DJ, O’Toole T (2016) Exposure to fine particulate air pollution is associated with endothelial injury and systemic inflammation. Circ Res 119:1204–1214

Rauchman M, Griggs D (2019) Emerging strategies to disrupt the central TGF-beta axis in kidney fibrosis. Transl Res 209:90–104

Song N, Zhang T, Xu X, Lu Z, Yu X, Fang Y, Hu J, Jia P, Teng J, Ding X (2018) miR-21 protects against ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury by preventing epithelial cell apoptosis and inhibiting dendritic cell maturation. Front Physiol 9:790

Stam F, van Guldener C, Becker A, Dekker JM, Heine RJ, Bouter LM, Stehouwer CD (2006) Endothelial dysfunction contributes to renal function-associated cardiovascular mortality in a population with mild renal insufficiency: the Hoorn study. J Am Soc Nephrol 17:537–545

Su R, Jin X, Zhang W, Li Z, Liu X, Ren J (2017) Particulate matter exposure induces the autophagy of macrophages via oxidative stress-mediated PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Chemosphere 167:444–453

Tanase DM, Gosav EM, Radu S, Costea CF, Ciocoiu M, Carauleanu A, Lacatusu CM, Maranduca MA, Floria M, Rezus C (2019) The predictive role of the biomarker kidney molecule-1 (KIM-1) in acute kidney injury (AKI) cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci 20:5238

Tavera Busso I, Mateos AC, Juncos LI, Canals N, Carreras HA (2018) Kidney damage induced by sub-chronic fine particulate matter exposure. Environ Int 121:635–642

Verma SK, Molitoris BA (2015) Renal endothelial injury and microvascular dysfunction in acute kidney injury. Semin Nephrol 35:96–107

Wang JS, Tseng CY, Chao MW (2017) Diesel exhaust particles contribute to endothelia apoptosis via autophagy pathway. Toxicol Sci 156:72–83

Wang W, Deng Z, Feng Y, Liao F, Zhou F, Feng S, Wang X (2017) PM2.5 induced apoptosis in endothelial cell through the activation of the p53-bax-caspase pathway. Chemosphere 117:135–143

Wang W, Zhou J, Chen M, Huang X, Xie X, Li W, Cao Q, Kan H, Xu Y, Ying Z (2018) Exposure to concentrated ambient PM2.5 alters the composition of gut microbiota in a murine model. Part Fibre Toxicol 15:17

Xu Y, Wang W, Zhou J, Chen M, Huang X, Zhu Y, Xie X, Li W, Zhang Y, Kan H, Ying Z (2019) Metabolomics analysis of a mouse model for chronic exposure to ambient PM2.5. Environ Pollut 247:953–963

Yan YH, Chou CKC, Wang JS, Tung CL, Li YR, Lo K, Cheng TJ (2014) Subchronic effects of inhaled ambient particulate matter on glucose homeostasis and target organ damage in a type 1 diabetic rat model. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 281:211–220

Zhang J, Liu J, Ren L, Wei J, Duan J, Zhang L, Zhou X, Sun Z (2018) PM2.5 induces male reproductive toxicity via mitochondrial dysfunction, DNA damage and RIPK1 mediated apoptotic signaling pathway. Sci Total Environ 634:1435–1444

Zhang Y, Hu H, Shi Y, Yang X, Cao L, Wu J, Asweto CO, Feng L, Duan J, Sun Z (2017) (1)H NMR-based metabolomics study on repeat dose toxicity of fine particulate matter in rats after intratracheal instillation. Sci Total Environ 589:212–221

Zhang Y, Li S, Li J, Han L, He Q, Wang R, Wang X, Liu K (2018) Developmental toxicity induced by PM2.5 through endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy pathway in zebrafish embryos. Chemosphere 197:611–621

Zhang YH, Zhang YQ, Guo CC, Wang LK, Cui YJ, Dong JJ, Liao L (2019) Prostaglandin E1 attenuates high glucose-induced apoptosis in proximalrenal tubular cells by inhibiting the JNK/Bim pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin 41:561–571

Zhou B, Liang G, Qin H, Peng X, Huang J, Li Q, Qing L, Zhang L, Chen L, Ye L, Niu P, Zou Y (2014) p53-dependent apoptosis induced in human bronchial epithelial (16-HBE) cells by PM(2.5) sampled from air in Guangzhou, China. Toxicol Mech Methods 24:552–559

Zhou T, Hu Y, Wang Y, Sun C, Zhong Y, Liao J, Wang G (2019) Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) aggravates apoptosis of cigarette-inflamed bronchial epithelium in vivo and vitro. Environ Pollut 248:1–9

Zhou Z, Shao T, Qin M, Miao X, Chang Y, Sheng W, Wu F, Yu Y (2018) The effects of autophagy on vascular endothelial cells induced by airborne PM2.5. J Environ Sci (China) 66:182–187

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81872720), the Outstanding Clinical Discipline Project of Shanghai Pudong (Grant No. PWYgy2018-10), Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (Grant No. 201840066), the Shanghai Key Laboratory of Meteorology and Health (Grant No. QXJK201612 and QXJK201805), and Science and Technology Program of Education Department of Jiangxi province (GJJ180573).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LZ and JL designed the research; XH, ZZ and XL conducted the in vivo and in vitro studies and data analyses; XH, JL and LZ wrote the draft of initial manuscript; XH, LZ and JL contributed to the interpretation of the data and preparation of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was subject to approval by the institutional animal care and use committees of Tongji University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that all authors have no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, X., Zhou, Z., Liu, X. et al. PM2.5 exposure induced renal injury via the activation of the autophagic pathway in the rat and HK-2 cell. Environ Sci Eur 32, 97 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-020-00378-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-020-00378-7